Abstract

Coxsackieviruses are important human pathogens, and their interactions with the innate and adaptive immune systems are of particular interest. Many viruses evade some aspects of the innate response, but coxsackieviruses go a step further by actively inducing, and then exploiting, some features of the host cell response. Furthermore, while most viruses encode proteins that hinder the effector functions of adaptive immunity, coxsackieviruses and their cousins demonstrate a unique capacity to almost completely evade the attention of naive CD8+ T cells. In this article, we discuss the above phenomena, describe the current status of research in the field, and present several testable hypotheses regarding possible links between virus infection, innate immune sensing and disease.

Keywords: adaptive immunity, autophagy, coxsackievirus, innate immunity, loop pathogenesis, mitochondria, picornavirus, RIG-I-like receptor, T cell, Toll-like receptor

Type B coxsackieviruses (CVB) are important human pathogens that cause both acute and chronic diseases. Infants, young children and immunocompromised individuals are particularly susceptible [1–3], and severe morbidity and mortality can result. CVB are the most common cause of infectious myocarditis, a serious disease that can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and cardiac failure [4–6], and these viruses also frequently induce pancreatitis and aseptic meningitis [1,7–10]. CVB belong to the picornavirus family and enterovirus genus; this large genus has recently been reorganized and now contains ten species. The ‘type species’ of the genus is human enterovirus C (a species that includes the three strains of poliovirus). CVB are members of the closely related species human enterovirus B, which contains a total of approximately 60 serotypically distinct agents, the six serotypes of CVB (CVB1–6) and numerous echoviruses and other enterovirus isolates. Our primary purview herein is to discuss the interactions between CVB and the innate and adaptive immune systems, but at times our focus will broaden to include other viruses. Furthermore, we will present a number of speculative, but testable, hypotheses regarding the interactions between viruses and innate immunity, and the possible implications for pathogenesis. Below we summarize data obtained from both tissue culture studies and from animal models (in this article, the term ‘in vivo’ refers only to the latter). Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, the time of cellular infection can be more exactly determined in tissue culture than in vivo and this, together with the relative uniformity of tissue culture cells, facilitates biochemical evaluation of the kinetics of virus growth and intracellular changes. However, tissue culture experiments may often employ cells that support very efficient virus replication, providing the virus with a greater opportunity to overwhelm any attempt by the cell to constrain it; whereas in vivo, the virus encounters many different cell types in which its ability to replicate may vary widely. Finally, of course, in vivo replication must take place in the face of both innate and adaptive immune responses, whereas only the former may be relevant in some tissue culture analyses.

Innate immune responses to coxsackieviruses

For many years, immunological research focused almost exclusively on adaptive immune responses, exemplified by the antibodies and T cells that are the cornerstone of natural and vaccine-induced immune protection against microbial challenge. However, over the past decade, the importance of the innate immune response to virus infection has become increasingly clear. The innate response to viruses is usually activated via one (or more) of three general sensor pathways; Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). Little is known of the interactions between CVB and NLRs, and so these will not be discussed herein. Triggering of TLRs and RLRs alters the expression of hundreds of genes and thus has pleiotropic effects. Most relevant to this article, a variety of cytokines, chemokines and other proteins are induced that act at two biological levels. First, some of them can directly counter virus infection: examples include protein kinase regulated by RNA (PKR; discussed below) and type I interferons (T1IFNs). Second, some of them help to activate the adaptive immune response (e.g., by upregulating MHC molecules and co-stimulatory molecules on dendritic cells [DCs] or promoting T-cell division): examples include IFNγ and IL-2. Some innate effector molecules do both of the above; for example, T1IFNs and IFNγ. In describing the interactions between CVB and the innate response, our focus is on how the cell senses the presence of the virus; the other side of the coin, the manifold effector mechanisms by which the activated innate immune system can combat viruses, is beyond the scope of this article.

CVB & TLRs

Toll-like receptors are type I transmembrane glycoproteins, and are expressed on several immune cell types (e.g., DCs, macrophages, B cells, natural killer [NK] cells) and on various non-immune populations (some fibroblasts, endothelial and epithelial cells) [11]. To date, ten TLRs have been identified in humans, and 13 in mice. TLRs fall into two categories, characterized by their cellular location and the types of microbial molecules by which they are activated. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 and TLR6 are expressed on the cytoplasmic membrane, where they are positioned to interact with extracellular stimuli. Most of these TLRs are activated by microbial proteins or lipids (e.g., viral envelope proteins, lipopolysaccharide [LPS] and flagellin). In contrast, TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are contained in intracellular vesicles, and are activated by molecules that are present in the vesicular lumen; these TLRs act as sensors for nucleic acids (TLR3: dsRNA; TLR7/8: ssRNA; TLR9: unmethylated CpG DNA).

Both cell surface and internal TLRs have been implicated in the immune response to CVB. TLR4 is expressed on the cell surface and is usually activated by the bacterial product LPS, but this TLR also has been implicated in sensing of several viruses [12,13]. TLR4 on human pancreatic cells appears to be triggered by CVB4 [14], and TLR4-knockout (KO) mice infected with CVB3 show reduced virus titers and myocarditis [15]. A comparison of male and female mice confirmed that TLR4 signaling was correlated with the severity of myocarditis [16]. However, CVB-mediated triggering of TLR4 must be suboptimal, because LPS and related compounds administered concordantly with CVB greatly increase the severity of CVB-induced myocarditis [17,18].

The intravesicular sensor TLR3 senses dsRNA molecules, which are commonly produced during the replication of RNA viruses, as well as the synthetic molecule polyI:C [19]. Compared with wild-type mice, TLR3KO mice are highly susceptible to CVB3 infection, displaying increased mortality and developing more severe myocarditis [20]; the latter finding was confirmed by others [21]. A recent study of CVB4 infection of TLR3-defcient mice led the authors to conclude that TLR3 was not only central to the innate response to CVB, but was almost indispensable [22]. However, the relative importance of the various nucleic acid-sensing TLRs is controversial, because several others can play an important part in controlling CVB infections. For example, human cardiac inflammatory responses to CVB are reported to be dependent largely on TLR7 and TLR8 [23], both of which recognize ssRNA and other small molecules [24]. TLR7 and TLR8 have extensive sequence homology and are closely linked on the X chromosome. It has been suggested that there is functional redundancy between the two, perhaps explaining why rodent TLR8 carries a five-amino-acid deletion that renders it almost nonfunctional [25]. In contrast to the murine protein, human TLR8 is highly responsive to ligand, and this raises a cautionary flag; when compared among different animal species, TLRs show a substantial degree of polymorphism [26]. TLR polymorphisms occur even within a species, and can significantly affect an individual’s susceptibility to infection and disease caused by a particular microbe [27], so it is reasonable to suggest that the wider variation that is observed among species may play some part in determining the species-specificity of some microbial infections. Therefore, we must bear in mind that studies of TLR (and other) innate responses in animal models may not accurately parallel human innate responses to infection.

Where might CVB, or CVB products, encounter these TLRs? It is relatively easy to imagine how extracellular microbes, including CVB virions, might activate cell surface TLRs by direct physical contact, and the fact that UV-inactivated CVB4 can activate cells via TLR4 is consistent with this mechanism [14]. However, one cannot assume this to be the case, because CVB4 does not appear to interact directly with the TLR4 protein; the means by which the virus activates the receptor are unknown [14]. It is still more challenging to identify where CVB RNAs might intersect with intravesicular TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9, because CVB replication takes place in the cytosol. Two possibilities may be considered. First, that the interaction between CVB RNAs and TLRs takes place during cell entry; and, second, that it occurs when CVB RNAs, perhaps during replication, are engulfed by autophagosomes that fuse with endolysosomes or similar vesicles that contain these TLRs. We shall consider both possibilities below.

Do enteroviral RNAs interact with TLRs during cell entry?

Fluorescently labeled CVB RNA, transfected into cells using cationic lipid reagents, co-localizes with TLR7 and TLR8 in endosomes [23]. This is interesting, but may not reflect the fate of viral RNA during a normal infection. Despite many years of study, picornaviral entry processes remain relatively poorly understood. Much effort was expended on studying the major human pathogen, poliovirus, and until very recently, it was thought that the capsid bound to the cell surface and altered conformation, thereby generating a pore in the cytoplasmic membrane through which the viral genomic RNA was extruded into the cytosol [28]. Under such circumstances, it is difficult to determine how the viral RNA might encounter TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 or TLR9 during the entry process. A recent and elegant live imaging study has shown that (at least in HeLa cells) poliovirus entry is endocytic, with the virus budding into the cell; however, the viral RNA is released into the cytosol very rapidly thereafter, before the entry vesicle has transited more than approximately 100 nm into the cell [29]. It seems unlikely that these poliovirus entry vesicles will contain the aforementioned TLRs, which are not present on the cell membrane, and are introduced only after fusion with vesicles traveling from the endoplasmic reticulum; thus, this modified picture of poliovirus entry does not afford an obvious means by which the incoming viral RNA could trigger internal TLR responses. Upon binding to their cellular receptor coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, CVB virions also undergo a conformational change [30], and, like poliovirus, CVB RNA release appears to occur only after internalization, at least in polarized cells [31]. Virion internalization into polarized cells appears to be mediated by a process similar to macropinocytosis [32]. However, additional studies (by the same group) of CVB entry into nonpolarized (HeLa) cells indicated that a different mode of entry applied [33]. Thus, at present, it seems reasonable to conclude that CVB cell entry differs depending on the cell type; that we do not yet know precisely where the viral RNA is released into the cytosol; and that, consequently, more investigation is required to identify where and how CVB ssRNA and/ or dsRNA might directly interact with TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9. An intriguing possible explanation exists for cells that express Fc receptors. CVB may enter plasmacytoid DCs (pDC) only when bound to CVB-specific antibodies, and pDC TLR7 is activated only when CVB-specific antibodies are present [34]. Perhaps Fc-related internalization directs the incoming virus to a pathway that intersects with these TLRs, thereby permitting the rapid activation of innate immunity in cell types that are pivotal to the host immune response.

Do enteroviral RNAs interact with TLRs later in the replicative cycle?

Intuitively, one would imagine that tripping of the innate alarms would become more likely as the abundance of viral RNA increased, as occurs during viral replication. However, it remains unclear how intravesicular TLRs would intersect with CVB3 RNAs, because CVB replication is thought to take place in the cytosol. One possible means by which CVB RNAs might be translocated into endosomes is macroautophagy, a homeostatic cellular process in which cytosolic materials are engulfed, degraded and recycled through lysosomes. Macroautophagy (from here on referred to as ‘autophagy’) is an ancient process, the origins of which can be found at the roots of the eukaryotic tree, and it may have developed in concert with the acquisition of mitochondria; indeed, the present-day autophagy pathway can be activated by mitochondria, to trigger their removal during the maturation of certain cell types (e.g., as reticulocytes mature into erythrocytes) and if they are defective [35]. The evolutionary history of autophagy is consistent with the current concept that, in general, it plays a protective function during infection; for example, by sequestering and degrading bacteria and protozoa in a process known as ‘xenoph-agy’ [36]. Autophagy may be important in the innate response to certain viruses. For example, autophagy protects against CNS infection by Sindbis virus; apparently the cellular sequestosome adapter protein p62 interacts with the Sindbis capsid protein, targeting the capsid proteins to autophagosomes [37]. Furthermore, cytosolic replication intermediates of this and another RNA virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), are transported into lysosomes by autophagy, and cells that have been rendered deficient in autophagy are unable to respond to these infections [38]. It is interesting to note that autophagy itself is upregulated by TLRs, and that the most potent pro-autophagic effects are mediated by ssRNA/TLR7 signaling [39]. This raises the fascinating possibility of there being a positive-feedback loop within an RNA virus-infected cell, in which the normal process of constitutive autophagy will introduce some RNA into endolysosomes; this triggers TLR7 which, in turn, upregulates autophagy, thereby increasing delivery of RNA to endosomes and ensuring maximal TLR7 signaling within the infected cell. This proposed loop and additional facets of the CVB-related innate response are illustrated in Figure 1.

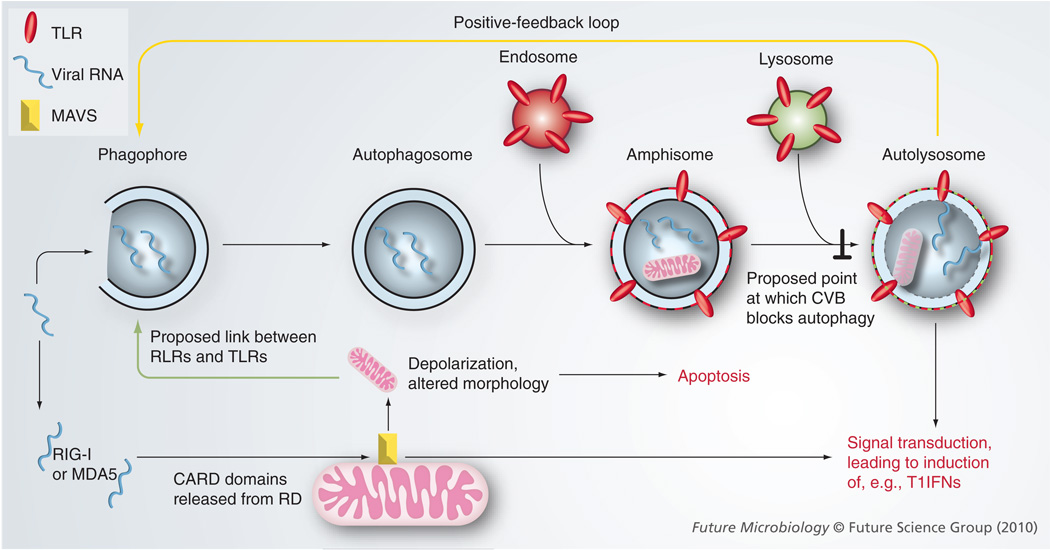

Figure 1. Proposed intersections between type B coxsackievirus RNA, Toll-like receptors, RIG-I-like receptors, mitochondria and autophagy.

This representation of the hypotheses presented in the text helps explain cellular innate responses to CVB infection. Viral RNA (blue lines) releases the CARD domains of the cytosolic RNA sensors (RIG-I and MDA5) from their RD. By binding to MAVS (yellow bar), a signal transduction cascade is triggered, leading to induction of type I IFNs etc (lower right of cartoon). However, we speculate that MAVS binding has additional effects. We propose that mitochondria act as a bridge (green arrow) between the cytosolic RNA sensors (RIG-I, MDA5) and the intravesicular TLRs, as follows: mitochondrial depolarization occurs, upregulating autophagy; this increases the uptake of viral RNA into the autophagy pathway, thereby introducing this RNA to the nucleic acid-sensing TLRs (red ovals) in acidified autolysosomes. A positive-feedback loop (yellow arrow) ensures the rapid amplification of these RLR-initiated, TLR-propagated innate responses. Finally, we suggest that, as infection progresses within the cell, viral proteins may become sufficiently abundant to obviate the feedback loop by inhibiting autophagosomal maturation (┴), thereby limiting the amount of viral RNA that encounters TLRs.

CARD: Caspase-recruitment domain; CVB: Type B coxsackieviruses; MAVS: Mitochondrial antiviral signaling; RD: Repressor domains; RLR: RIG-I-like receptor; TLR: Toll-like receptor.

CVB, autophagy & TLRs

How do CVB and other enteroviruses interact with the autophagy pathway? An association between poliovirus and double-membraned intracellular vesicles was first reported 45 years ago, from electron microscopic studies of poliovirus-infected cells [40]. A subsequent elegant analysis confirmed this observation and suggested that the vesicles might be autophagy-related [41]. The viral 2BC and 3A proteins seem to play a key role in the membrane remodeling that takes place in a poliovirus-infected cell [42], and the resulting vesicles, although smaller than constitutive autophagosomes [43], nevertheless bear several proteins that are characteristic of these structures [44]. These findings, made from studies of poliovirus, appear to also apply to CVB. A relationship between CVB and autophagic vesicles was first suggested some 35 years ago, from observations of pancreata from CVB4-infected mice [45], and more recent electron microscopic reports have revealed a dramatic increase in double-membraned structures within CVB-infected cells [46,47]. Such observations are consistent with autophagy playing a protective role during these viral infections, but experimental investigation has revealed the opposite. Stimulation of autophagy in poliovirus-infected tissue culture cells increases virus yield, while pharmacological inhibition has the opposite effect [48], although in both cases the effect was modest (two- to threefold). Similarly, blocking autophagy in HeLa cells leads to an approximate threefold reduction in CVB3 replication within those cells [46], although a greater (~30-fold) effect has been reported for CVB4 infection of primary neurons [47]. Enteroviruses are not alone in exploiting autophagy. The yield of influenza A virus is reduced if autophagy is inhibited [49], and the autophagy pathway promotes replication of hepatitis B [50] and C viruses [51]. Therefore, several viruses appear to exploit the autophagy pathway, harnessing it as a source of vesicles that serve as a replication platform [52].

How might viruses best achieve this end? Conceptually, the abundance of autophagic vesicles could be increased in two ways: first, by increasing their production and, second, by preventing their maturation. To date, the latter strategy appears the more common; autophagosomes are immobilized in poliovirus-infected cells [53], perhaps because they cannot be translocated along microtubules to their eventual fusion with lysosomes to form autolysosomes [54]. Similarly, both influenza virus [55] and HIV [56] appear to inhibit fusion between autophagosomes and endosomes and/or lysosomes. Others have proposed that poliovirus immobilizes the autophagosome in order to delay the release of virus to the extracellular space [53]. Here we propose an alternative explanation: viruses that ‘paralyze’ autophagosomes prior to fusion with endolysosomes will disrupt the positive-feedback loop described above, allowing these agents to minimize the exposure of their RNAs to intravesicular TLRs, thereby delaying activation of the intracellular innate response (Figure 1). One objection to this hypothesis is that the polio-virus-induced double-membrane vesicles often stain positive for the protein LAMP-1, which is considered a marker of late endosomes as well as lysosomes; surely, then, these vesicles must contain the nucleic acid-sensing TLRs? This concern also applies to CVB3; our laboratory has identified co-localization between viral proteins and LAMP-1 in maturing autophagosomes [Unpublished Data]. There are several possible rebuttals to this objection: first, in resting DCs, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 reside mostly in the endoplasmic reticulum, and upon cell activation these proteins translocate to endolysosomes [57,58]. Consequently, it is possible that the endosomes with which autophagosomes fuse will not contain TLRs; second, even if TLRs are present, the RNA in a newly formed amphisome remains separated from the TLRs by a lipid bilayer, as shown in Figure 1; and third, early endosomes have a near-neutral pH, which they may maintain for some time after their formation [59], but all four nucleic acid-sensing TLRs require an acidic pH for activation. TLR3 activation by dsRNA requires an acidic compartment [57], and the same is true for the activation of TLR7 by ssRNA [60,61]. TLR9 activation by CpG DNA occurs only in lysosomes [62], which are highly acidic, and is prevented by chloroquine, which reverses lysosomal acidity [63]. For TLR9, a molecular explanation for the acidic requirement has been established; the TLR9 protein is inactive until cleaved by a lysosomal acid protease [64].

In summary, the exact point at which enteroviruses arrest autophagosome maturation is unknown; we speculate that it occurs after endosomal fusion, but prior to encountering TLRs and/or to vesicular acidification, thereby minimizing the activation of the RNA-sensing TLR3, TLR7 and TLR8.

CVB & RLRs

RIG-I-like receptors have three known members: RIG-I, MDA5 and LGP2. All three sensors are activated by nucleic acids and are expressed in the cytosol of most cell types; although very recent work suggests that there may be substantial heterogeneity in RIG-I and MDA5 expression among different classes of DC [65]. MDA5 is distributed throughout the cytosol, but RIG-I appears to co-localize with F-actin and, therefore, is associated with the cytoskeleton [66]. The best-characterized of the RLRs are RIG-I and MDA5. Both of these proteins are RNA helicases with ATPase activity, and contain two N-terminal caspase-recruitment domains (CARDs). A repressor domain (RD) is present at the C-terminus of both sensors, and this motif appears to render the CARDs inactive [67,68]. Ligand binding activates the ATPase activity; this, in turn, leads to a conformational change that releases the CARDs from RD-mediated repression, allowing them to initiate the signaling cascade. For both RIG-I and MDA5, the CARDs interact with an adapter molecule that resides on the outer mitochondrial membrane (and, very recently, has been identified on peroxisomes, see [69]), and which has been associated with a bewildering variety of names: mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) [70], virus-induced signaling adaptor [71], CARD adaptor-inducing IFNβ [72] and IFNβ promoter stimulator-1 [73]. Herein, we shall use the term ‘MAVS’. CARD binding to MAVS recruits a signaling complex that induces transcription of IFNβ, and also of genes that are regulated by IRF3 (including the T1IFNs) and NF-κB.

The relative antiviral contributions of RIG-I and MDA5 differ depending on the virus involved [67]. RIG-I recognizes both dsRNA and ssRNA, and a 5´-triphosphate is required for recognition [74,75]. During their lifecycles, most RNA viruses produce abundant quantities of dsRNA and ssRNA molecules that carry this terminal moiety and, therefore, these viruses strongly activate RIG-I; the importance of this sensor is demonstrated by its absence, which compromises or disables the innate response to several RNA virus families [68]. RNAs that lack the 5´-triphosphate moiety do not stimulate RIG-I and, therefore, capped mRNAs (e.g., host cell mRNAs and most DNA virus mRNAs) do not activate RIG-I. Most relevant to this article, nor does picornaviral RNA, the 5´-end of which carries a modified protein (virus genome-linked protein) that acts as the primer for RNA replication, and allows the virus to evade the attention of RIG-I. Consistent with this observation, mice lacking RIG-I do not show increased susceptibility to picornavirus infection [67]. The RIG-I protein is degraded in cells infected with a variety of picornaviruses [76], but the biological significance of this observation is uncertain because, as the authors point out, RIG-I appears to contribute little to the innate response to these agents. As mentioned earlier, RIG-I is associated with the cytoskeleton, and it recently was shown that cytoskeletal disruption led to the intracellular redistribution of RIG-I, and to the induction of T1IFN signaling [66]. The authors noted that many infections commonly alter the cytoskeleton, and they suggested that cytoskeleton integrity itself may act as a very early, RIG-I-mediated, sensor of infection. This is an attractive and intriguing possibility, but comes with a conundrum: poliovirus and CVB3 both cause massive reorganization of the cytoskeleton [77,78], but neither of these viruses triggers RIG-I-mediated activation. This apparent paradox awaits resolution.

Fortunately, evolution has provided MDA5 as an alternative cytosolic sensor that allows picornavirus-infected cells to mount a rapid innate response. MDA5 is triggered by the picornavirus encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) [67,79], reoviruses [68] and some, but not all, flaviviruses [68,80,81]. The natural ligand(s) for MDA5 remains poorly defined, and currently is thought to be long dsRNA (>1–2 kb in length [82]). However, one might expect that long dsRNA would be present in most RNA virus-infected cells, leading to an obvious question: why does MDA5 appear to be activated only by relatively few RNA viruses? The answer may be deceptively simple; the general conclusion itself may be too sweeping. Early studies indicated that paramyxo-viruses could not activate this sensor, but recent studies have strongly contested that conclusion both in vitro [83] and in vivo [84]: norovirus is recognized by MDA5 [85]; and measles virus appears to activate both RIG-I and MDA5 [86]. Thus, the number of viruses that can be recognized by MDA5 is increasing, and in several cases there is overlap with RIG-I (i.e., both sensors are triggered by certain viruses).

Two recent publications have described the in vivo effects of MDA5 on CVB3 infection [87,88], and, perhaps because the MDA5KO mice were generated independently by each group, the authors reached somewhat different conclusions concerning at least two important criteria: T1IFN production and virus titers. One group reported a large and statistically significant reduction in T1IFN production by CVB3-infected MDA5KO mice when compared with wild-type mice, but, surprisingly, the reduction in this key antiviral effector molecule was not accompanied by any significant increase in CVB3 titers in the MDA5KO animals [87]. In contrast, the second group found no significant difference in T1IFNs, but virus titers in several tissues of the MDA5KO mice were markedly (at least 5 logs) higher than in wild-type tissues at 3 days post-infection [88]. Notably, this difference had vanished just 24 h later, at which timepoint the CVB3 titers in wild-type tissues had risen to match those observed in the MDA5KO tissues [88]. Therefore, at the time of writing it seems possible that: MDA5 plays an important role in regulating CVB titers very early in infection; the effect is transient, serving only to delay the production of progeny virus; and this short-lived effect may not be mediated by T1IFN. We speculate that the early and immediate control of CVB3 relies on MDA5/MAVS signaling through peroxisomes, rather than through mitochondria; this pathway has been shown to be independent of T1IFN signaling in other models of virus infection [69]. This MDA5-mediated constraint on virus replication, although fleeting, appears to be a very important determinant of CVB3 pathogenesis; in both reports, MDA5KO mice developed more extensive pancreatic and hepatic necrosis. MDA5, like RIG-I, is degraded in poliovirus-infected HeLa cells, providing one possible mechanism by which enteroviruses might paralyze the innate immune response [89]; however, the profound effects of MDA5 deficiency during CVB3 infection indicate that, if MDA5 degradation occurs at all in CVB-infected cells, the process must not go to completion.

LGP2 lacks a CARD, and several early studies suggested that LGP2 might suppress RIG-I signaling and, perhaps, signaling via MDA5 [90–93]. Two laboratories have generated LGP2KO mice and have evaluated their phenotypes, which appear to differ quite substantially. One mouse strain demonstrated increased responses to polyI:C, and enhanced resistance to VSV, leading the authors to conclude that (as had previously been proposed) LGP2 might act as a negative regulator of the T1IFN responses that are induced by RIG-I and/or MDA5 [93]. In contrast, Satoh et al. reported that fibroblasts from their LGP2KO mice responded normally to polyI:C, but had reduced responses to VSV, suggesting that LGP2 might exert positive effects [94]. Some commonalities were present; both mouse strains showed a markedly enhanced susceptibility to picornaviruses. Thus, to date, cumulative data suggest that LGP2 may, in some circumstances, contribute positively to the innate antiviral response.

Finally, and possibly relevant to both TLR-and RLR-mediated responses to CVB, infection is not the only way in which viral materials can enter some cells. Many cells (e.g., macrophages and DCs) are phagocytic and engulf dead or dying cells. Human DCs cannot be productively infected by CVB [95], but can take up debris from CVB-infected cells, inducing an antiviral state in the DCs [96]. Acquisition of the antiviral state was prevented by chloroquine, implicating intravesicular TLRs in the phenomenon [96].

CVB, MAVS, mitochondria & autoimmunity

The RLR signaling adaptor MAVS is important in signaling by both RIG-I and MDA5, and mice lacking MAVS are markedly more susceptible to infection by various viruses [97], including the picornavirus encephalomyocarditis virus [83]. Furthermore, these mice exhibit increased mortality following CVB3 infection [87]. It is interesting to note that another picornavirus, hepatitis A virus, encodes a protease that contains a motif that targets it to the mitochondrion, where it co-localizes with, and cleaves, MAVS [98].

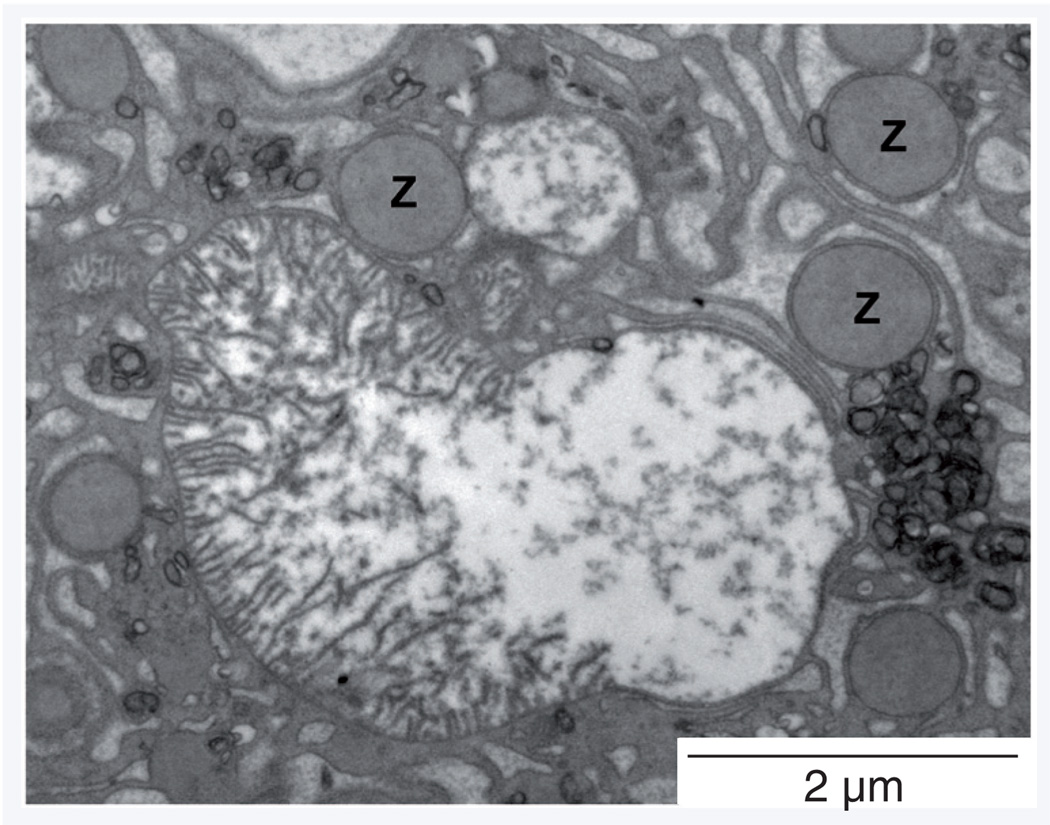

The importance of MAVS in innate anti viral responses is clear, but the molecule also has other functions. It has long been known that mitochondria play a key role in modulating the cell death pathways, and very recent work suggests that MAVS may be central to this phenomenon. MAVS activation leads to mitochondrial depolarization and initiates cellular apoptosis, thereby regulating cell death [99,100]. The proapoptotic function of MAVS is separable from its role in IFN induction [99], but RLR-initiated signaling alters mitochondrial morphology [101], and RNA virus-induced cell apoptosis appears to be dependent on MAVS [99]. Although this work is at an early stage, these data suggest that RLR signaling not only induces IFN production, but also triggers changes in mitochondria, leading to apoptosis. We noted earlier that changes in mitochondrial status also upregulates autophagy; therefore, herein, we speculate that RLR signaling, activated by RNA viruses, will alter mitochondrial physiology, thereby upregulating autophagy (green arrow in Figure 1) and thus increasing delivery of viral and mitochondrial materials to intravesicular TLRs. If correct, this suggestion defines mitochondria as a point of intersection for apoptosis, the autophagy pathway and RLR signaling; all of which play important roles in innate antiviral immunity. One prediction of this hypothesis is that mitochondrial pathology would be observed during CVB infection. Ultrastructural analysis of pancreatic acinar cells from mice infected with wild-type CVB3 reveals multiple instances of mitochondria that are misshapen, and/or in the process of degradation; an example of the latter is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mitochondrial degradation in a type B coxsackievirus-infected pancreatic acinar cell in vivo.

Transmission electron microscopy image (magnification: ×10,500) of a pancreatic acinar cell from a mouse, 48 h after infection with Type B coxsackieviruses 3. A mitochondrion in the process of degradation is shown.

Z: Zymogen granules.

This proposal has several interesting implications, for example, in disease pathogenesis. Consider the autophagy/TLR positive-feedback loop that, we speculate above, exists within a virus-infected cell; this feedback could now be triggered (through mitochondria) by virus-induced RLR signaling. The benefit of such a positive-feedback loop is clear for a single virus-infected cell, which is already doomed to die; but positive-feedback loops are intrinsically ‘risky’ biological strategies which, if released from their normal constraints, can cause immense harm to the host. A delicate balance exists, clearly demonstrated by the fact that as little as a twofold increase in TLR7 gene dosage is sufficient to initiate autoimmune disease [102]. A TLR7-related positive-feedback loop has been proposed as a driving force of the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus [103], in which mitochondrial dysfunction appears to play a central role [104,105]; the general term ‘loop pathogenesis’ has been coined to describe this disease mechanism [11]. We speculate that loop pathogenesis, which could be triggered by RNA viruses (via TLR7/RLRs) or by DNA viruses (e.g., via TLR9), represents dysregulation of innate pathways that have evolved to counter virus infection. This could explain the frequent, but ill-understood, relationship between virus infections and autoimmune diseases.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D; insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) is thought to be an autoimmune disease, and many environmental factors have been proposed as triggers. Several clinical studies have shown correlations between enterovirus infection and T1D, the strongest association being with CVB, but the biological significance of these data remains highly controversial. Over the years, various studies have suggested that immunological (antibody and/or T cell) crossreactivity between CVB and host proteins might explain the observed correlation [106–111]. However, recently, fascinating data have emerged to suggest that any causal relationship may be attributed to the innate immune system, rather than to the adaptive; a human genome-wide scan for nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified MDA5 as a T1D susceptibility locus [112]. Sequencing of this locus in diabetic patients and controls has revealed rare variants of the human MDA5 gene that protect against the development of T1D [113], and at least two of the variant proteins are incapable of signaling in response to dsRNA [114]. Thus, the inability to mount an innate response to virus infection may confer some degree of protection against the development of T1D. This concept can be framed differently: innate responses to virus infection may sometimes be harmful to your (islet cell) health. How might such harm accrue? Human islet cells mount strong innate responses, upregulating TLR3, RIG-I and MDA5, and they become resistant to CVB infection [115]. This resistance is, presumably, beneficial in the short-term, but one can imagine deleterious longer term consequences; perhaps T1D is an example of virus-triggered loop pathogenesis.

PKR

The final intracellular ‘sensor’ to be discussed is PKR. For many years, PKR was considered the major cellular sensor for dsRNA [116], but PKR protein is sparse-to-undetectable in most uninfected cells and, if present, its activity is tightly regulated [117]. As such, PKR is unlikely to be an initiator of the innate response, and it is now known that the responsibility for sensing the initial viral intrusion falls mainly to TLRs and RLRs. PKR expression is dramatically upregulated by IFN, after which its effector functions are activated by binding to dsRNA. PKR phosphorylates cellular proteins, thereby altering translation and signal transduction in virus-infected cells. Therefore, this protein is no longer considered a primary sensor; rather, it acts downstream as a key component of the innate antiviral effector pathway. As noted at the outset of the chapter, a detailed discussion of the many different innate antiviral effector mechanisms will not be presented herein.

NK cells

Natural killer cells have also been implicated in CVB infection, clearance and disease. These cells, which are part of the innate response to many infections, play a key role in protecting against pancreatitis in the mouse model [118]. NK cell recruitment to the CVB-infected heart, which may depend on the chemokine CXCL10 [119], is very rapid and precedes the arrival of T cells [120]. NK cells are one of the most abundant cell types in the inflammatory infiltrate [121], and appear to limit both CVB3 replication and virus-induced myocarditis [122,123]. Like T cells, NK cells can combat virus infection in at least two ways: first, by direct cytotoxicity (often perforin-mediated) and, second, by secretion of antiviral cytokines, such as IFNγ. The direct lytic effect of NK cells is inhibited by MHC class I and, therefore, NK-susceptible target cells usually have markedly reduced levels of these molecules. Infection by several picornaviruses, including CVB3, dramatically downregulates the amount of MHC class I on the cell surface (described in more detail below, see [124,125]), and this loss of NK-inhibitory activity in CVB-infected cells may explain the importance of NK cells in the mouse model. However, the same may not be true in humans. A recent study of CVB3-infected human cells showed that, despite significant reductions in MHC class I cell surface expression, the infected cells’ sensitivity to NK-mediated lysis was not increased [126]. What might explain this? As well as being ‘de-repressed’, NK cells also can be positively activated by specific ligands on the surface of potential target cells, but there was no change in the expression of these NK-activating ligands on the surface of the CVB3-infected human cells; perhaps positive signals are of particular importance for NK-mediated lysis of infected human cells [126].

Adaptive immune responses to CVB

The adaptive immune response has two arms, each reliant on a different class of lymphocyte. B lymphocytes (B cells) produce antibodies, which bind to infectious virions and reduce their capacity to infect cells. T lymphocytes (T cells) themselves come in several different flavors, each with its own function in the adaptive response. Herein, we shall be concerned mainly with CD8+ T cells, which recognize virus-infected cells and, by exerting their effector functions, diminish or prevent the production and shedding of new infectious progeny virions. Because antibodies recognize materials that are present in the extracellular milieu, they are effective in protecting against both bacteria and viruses. However, the same cannot be said for CD8+ T cells, which provide effective protection against many viruses, but few bacteria. Thus, during virus infection, both antibodies and CD8+ T cells contribute to protection, playing complementary roles with each easing the load on the other; but during most bacterial infections, antibodies alone stand between the organism and serious disease. Consistent with this, individuals who, genetically or iatrogenically, are unable to synthesize antibodies are acutely vulnerable to many bacterial infections.

In contrast, if the back-up mechanism provided by CD8+ T cells is intact, these individuals cope relatively well with several virus infections. For example, the seminal report describing the clinical consequences of agammaglobulinemia described a child who, in the years before diagnosis was made and gammaglobulin treatment was begun, experienced 19 episodes of suppurative bacterial infection [127]. However during that time the child had, and recovered normally from, chickenpox, a disease caused by the herpesvirus varicella-zoster (VZV). He also had, and recovered from, measles. Presumably, these recoveries were mediated by virus-specific T cells. Then, 5 years after his first VZV infection (and, ironically, after beginning gammaglobulin therapy) the patient developed shingles, a disease caused by recurrence of VZV. Thus, antiviral T-cell-mediated immunity confers substantial, albeit incomplete, protection against some virus infections. The authors of a classic paper on this subject described the outcomes of various virus infections in several agammaglobulinemic children, and concluded that “Children with agammaglobulinemia have a surprising ability to cope successfully with most virus infections in spite of their immunologic handicap” [128]. However, some picornaviruses, in particular some members of the enterovirus species, are a dramatic exception to that statement; these viruses cannot be effectively controlled in the absence of antibodies. We expand upon, and attempt to explain, this observation below.

Antibody responses to CVB

Type B coxsackieviruses infections induce rapid and strong neutralizing antibody responses. Predictably, IgM is first to appear, both in humans [129] and in mice [130]. As the CVB3-specific IgM titer wanes, the virus-specific IgG response rises and persists [130]. In discussing TLR7-driven innate responses to CVB, we noted that the process in pDCs depended upon CVB-specific antibodies [34], and some studies have suggested that CVB-specific antibodies might not only increase the response to infection, but also may enhance infection itself; this topic (antibody-dependent enhancement of virus infection during picornavirus infection) has recently been reviewed [131]. Analyses of humoral responses were, of course, the means by which the six types of CVB were originally defined, and some of the virus sequences that confer serotype-specificity have been identified. In humans, neutralizing IgM responses (both serotype-specific and crossreactive) are directed largely against the VP1 protein [129], and the same is true for IgG responses in infected mice [132]. Many antibody responses are dependent upon the B cells receiving help from CD4+ T cells, and some studies indicate that this may apply for CVB3; MHC class II−/− mice (in which CD4+ T-cell responses are severely compromised) develop weak, non-neutralizing CVB3-specific IgG antibodies [133]. However, other work leads to the opposite conclusion; T-cell-deficient (nude) mice develop neutralizing antibodies to CVB, albeit lower in titer than wild-type mice, suggesting that a portion of the CVB-specific antibody/B cell response is T-cell-independent [134,135], and CD4−/− mice can mount a neutralizing antibody response [121]. Gender-specific differences have been observed in the CVB3-specific antibody response, and this has been ascribed to the type of CD4+ T-cell help that is available in the infected host. Female BALB/c mice have a Th2-biased response to CVB, and generate more IgG1 isotype than IgG2a, whereas male mice have a predominantly Th1 response, and IgG2a is more prevalent [136].

The general rule that enteroviruses cannot be effectively controlled in the absence of antibodies applies to CVB. Several instances of CVB infections of agammaglobulinemic children have been reported; the infections spread to, and persist in, the CNS, causing severe, often fatal, meningoencephalitis [137–139]. Chronic infections by other enteroviruses are also well-recognized in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia [140], and include infections by several type A coxsackie-viruses [141,142]. The phenomenon also holds true for poliovirus. This is, perhaps, most dramatically demonstrated in people who received live poliovirus vaccine before they were known to have been agammaglobulinemic; the virus establishes a chronic infection in these individuals, and neurovirulent poliovirus may be shed in the stool for as many as 20 years post-vaccination [143]. Remarkably, long-term secretion of poliovirus has also been reported in a vaccine recipient in whom no immune dysfunction could be identified [144]. Parallel findings have been reported in the murine model of CVB3 infection. B-cell KO (BcKO) mice are incapable of resolving CVB3 infection, and develop a chronic infection characterized by high viral titers in many tissues, including the brain. High titers persist for the life of the animal and are accompanied by severe disease; for example, myocardial fibrosis and ventricular dilation that resembles the DCM that can occur in patients with chronic enterovirus myocarditis [145]. BcKO mice also have been used to assess the capacity of B and/or T cells to protect against CVB challenge. B and/or T cells from CVB3-immune mice were adoptively transferred to BcKO recipients, which then were infected with CVB3. Both cell types conferred some degree of protection but, as might have been predicted, B cells were more effective than T cells. Furthermore, transfer of B cells from CVB3-immune mice to chronically infected BcKO mice resulted in clearance of virus from all tissues, thereby recapitulating the effects of passive immunoglobulin therapy that is used to treat human agammaglobulinemia [145]. Finally, B cells have been shown to be a target of CVB infection, and may contribute to virus dissemination in the infected animal [145,146]. In sum, these data show that the humoral response plays a key role in combating coxsackievirus infections, and that the protective effects of CVB-specific T cells are less impressive.

The importance of antibodies in CVB infection is underlined by two additional findings: passive transfer of immunoglobulins reduces viral titers and disease in infected hosts [147]; and maternal antibodies (presumably transferred in breast milk) conferred protection upon newborn mice [148]. Maternal antibodies, or the lack thereof, may have contributed to the increased prevalence of poliomyelitis that was observed in developed countries during the first half of the 20th century. It is thought that exposure to poliovirus in early infancy, at a time when maternal antibodies are declining, but still present, allows the infants to develop their own acquired immune response, while still being protected against fulminant infection and disease. Substantial improvements in hygiene took place in the years leading up to the 1950s; as a result, first exposure to poliovirus was delayed to a point in later infancy or early childhood, when passively transferred maternal antibodies had waned [149]. In summary, control of enterovirus infection is heavily dependent on antibodies; and the above clinical picture suggests that, at least for this picornavirus genus, there may be some deficit in the back-up system that, for most viruses, is provided by CD8+ T-cell responses. We shall now discuss T-cell responses to CVB, and present a possible reason for the near-absolute requirement for antibodies in the control of these viruses.

T-cell responses to CVB

Early studies of the immune response to CVB found that mononuclear cells were important for control of viral replication [150]. CVB replicates to high levels in the heart of severe combined immunodeficiency mice (which lack mature T and B cells) and the infection is associated with severe myocarditis and high mortality 151]. T cells can help control CVB infection, although their importance varies among mouse strains. For example, viral replication and clearance are not affected in T-cell-deficient BALB/c mice [135], but, in contrast, the virus grows to higher titers and/or persists longer in T-cell deficient (nude) NFR and C3H mice [152,153]. Virus-specific cytotoxicity was demonstrated in vitro more than 30 years ago [154], and later studies showed that CVB3-infected mice mount both αβ and γδ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses, although in many cases the cytotoxic activity was directed towards uninfected cells, leading to the proposal that these viruses can trigger autoimmunity [155,156]. Within the αβ subset, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells help to limit viral replication, but this protection comes with a cost; the T-cell responses to CVB infection can cause extensive immunopathology and exacerbates myocarditis. In CD8-deficient C57BL/6 mice (β2m−/− or CD8-depleted CD4−/− mice), CVB3-associated myocarditis and mortality are diminished, but cardiac virus titers are substantially greater [121]. CD8+ T cells may be important for controlling CVB4: CD8−/− C57BL/6 mice infected with CVB4 have a higher incidence of mortality compared with controls; by contrast, CD8+ T-cell depletion of CVB4-infected BALB/c mice reduces mortality by 50% [157]. Experiments performed in other mouse strains (BALB/c, DBA/2, A/J) provide additional evidence that CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets can both contribute to myocarditis and/or pancreatitis in CVB infection [134,158,159].

CD8+ T-cell responses to CVB

CD8+ T cells specific for epitopes in the 3A, 3C and 3D proteins have been identified in human studies, but the ex vivo frequency of these cells was so low that their detection required approximately 2 weeks of in vitro peptide antigen re-stimulation [160]. Recently, two CVB3-specific CD8+ T-cell responses have been described in H-2b mice (Db/VP2285–293 and Kb/3D2170–217), but the frequency of these cells at day 8 post infection was remarkably low (<1% of CD8+ cells) and magnetic enrichment of the CD8+ T-cell population from the spleen and lymph nodes was required for their detection [161]. In another study, CVB epitopes on the H-2b background were predicted by computer algorithms, and the authors assessed peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in CVB-infected mice; even when a high level of stimulatory peptide was used in vitro, the observed responses were weak, at best [162]. One study with human subjects has also identified a low-frequency memory CD8+ T-cell response to an epitope in the CVB4 2C protein ex vivo [163]. All of these studies, in mice and men, are consistent with the general conclusion that CVB3 infection induces a remarkably weak primary CD8+ T-cell response. This is in contrast to many virus infections and antiviral vaccinations, in which virus-specific CD8+ T cells are abundant (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus [164], as well as vaccinia virus and yellow fever virus vaccines [165]).

In order to better evaluate epitope-specific T-cell responses to CVB3 in mice, our laboratory has generated a recombinant CVB3 (rCVB3.6) that expresses well-characterized CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell epitopes derived from lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. We have shown that neither wild-type nor rCVB3 induces marked activation of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells in vivo. The absence of a CD8+ T-cell response cannot be attributed to low intrinsic immunogenicity of CVB-encoded proteins, because expression of the same epitope sequence from a DNA vaccine induced a readily detected CD8+ T-cell response [166], and others have confirmed that DNA immunization with CVB3 VP1 induces CD8+ T cells [167]. Using epitope-specific CD8+ transgenic T cells as sensors to evaluate in vivo antigen presentation by rCVB3.6, we demonstrated that this virus almost completely inhibits antigen presentation through the MHC class I pathway, and is thus able to evade CD8+ T-cell immunity [168]. However, CVB-specific CD8+ memory T cells can confer some degree of protection to CVB3 challenge of a seronegative mouse [169]. These observations appear conflicting: if the virus prevents presentation via MHC class I, how can CD8+ memory T cells play any part in controlling CVB3 infection? This paradox is more apparent than real: CD8+ memory T cells can respond to much lower levels of MHC/peptide than naive CD8+ T cells [170], so we suggest that the quantity of MHC/epitope that is expressed on a cell infected with CVB3 (or another enterovirus) is: too low to trigger strong responses by naive CD8+ T cells (explaining the paucity of CVB-specific CD8+ T cells during primary infection) [168]; but sufficient to activate CD8+ memory T cells [166] (explaining why such cells can confer protection against CVB3 [169]). Thus, it appears that the blockade of MHC class I presentation, although profound, is incomplete. This is consistent with the reports of weak CD8+ T-cell responses that are cited above, and with the observation that tissue culture cells infected with rCVB3 show modest susceptibility to lysis by cytotoxic T-lymphocyte clones of an a ppropriate specificity [171].

Might CVB3 fail to induce strong T-cell responses by impairing the activation and/or function of DCs, including cytokine secretion and presentation of MHC-restricted viral epitopes? CVB3 infection of C57BL/6 mice leads to an increase in the frequency of pDC and CD11c+ DCs in the spleen, with twofold increase in the ratio of CD8+:CD4+ DC by day 8 [21]. Although positive-and negative-strand viral RNA is detectable in DCs in vivo, no infectious virus is produced, raising the possibility that a nonproductive infection impairs antigen presentation. At least two molecular mechanisms play a role in minimizing CVB epitope presentation by MHC class I. The CVB proteins 2B, 2BC and 3A can disrupt the Golgi apparatus, drastically reducing egress of proteins to the cell surface; and they also appear to enhance endocytosis, thereby internalizing proteins that were present on the cell surface [124,125,172–176]. By these means, the virus creates a cocoon in which it is invisible to CD8+ T cells (by virtue of the low level of MHC class I antigen presentation); and, possibly, untouchable by cytokines (because the cell surface will have been denuded of receptors for these molecules). For reasons discussed elsewhere [168], our observations raise interesting questions regarding the biological effectiveness of cross-presentation, a process in which antigen is taken up by a specialized subset of DCs, and is presented to naive CD8+ T cells [177]. Studies of poliovirus that preceded the CVB work indicate that similar conclusions regarding the weakness of CD8+ T-cell responses, and the underlying reason, may apply to this agent [178–181]. Interestingly, virus-specific CD8+ T cells expand poorly when stimulated with poliovirus-infected DCs, which may be attributed to the finding that poliovirus infection dampens MHC class I presentation. In contrast, MHC class II antigen presentation is preserved in poliovirus-infected DCs, and these antigen-presenting cells are able to stimulate poliovirus-specific CD4+ T cells [182,183].

CD4+ T-cell responses to CVB

CVB4-specific T-cell lines derived from human donors recognize peptide epitopes within the capsid proteins that are conserved among other enteroviruses [184]. T cells cultured from virus-infected mice proliferate in vitro when stimulated with synthetic peptides representing CVB3 VP1 sequences [185], and VP1-reactive CD4+ T-cell clones have been isolated [136]. CD4+ T-cell responses against a native epitope in coxsackievirus B4, or foreign epitopes engineered into recombinant CVB4, have also been detected in mice [186]. CVB3-induced CD4+ T cells can protect non-obese diabetic mice against the development of T1D [187]. This finding is somewhat unexpected, given the proposed relationship between CVB and T1D that is discussed above, and depends upon the activation of CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). In our aforementioned assessment of CD8+ T-cell responses using T-cell receptor-transgenic T-cell probes, we used the same approach to evaluate CVB-induced CD4+ T cells. In contrast to the poor presentation by MHC class I, we found that MHC class II-restricted viral epitopes are presented at a level that can drive primary CVB3-specific CD4+ T-cell responses. Using several criteria, these CVB-specific CD4+ T cells are normal: they show an effector phenotype with a Th1 cytokine profile; develop into memory CD4+ T cells that multiply dramatically following re-challenge; and quickly mature into secondary effector cells that can secrete multiple cytokines [168]. Nevertheless, activation of CD4+ T-cell responses was weaker than might have been anticipated. A very recent study showed that autophagy was important to antigen presentation by MHC class II [188]; one wonders if the inhibitory effects of CVB3 on autophagy might contribute to the diminution of virus-specific CD4+ T-cell responses.

γδ T-cell responses to CVB

Groundbreaking studies by Huber and colleagues have shown that two subsets of γδ T cells play opposing roles in shaping the adaptive CVB3-specific CD4+ T-cell response. Vγ4 T cells enhance susceptibility to viral myocarditis, whereas Vγ1 T cells have the opposite effect [189]. Vγ4 T cells promote a Th1 CD4+ T-cell response by a mechanism requiring IFNγ and CD1d, and dampen the Th2 response though Fas-dependent lysis of Th2 CD4+ T cells [190–194]. γδ T cells may also enhance a Th1 CVB3–specific CD4+ T-cell response by restraining FoxP3+ Tregs; depletion of γδ T cells in CVB-infected mice increases the numbers of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs, corresponding with a decrease in the number of activated (CD69+), effector phenotype (CD62LloCD44hi) and IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells in the spleen and heart [195].

CVB persistence

It is important, in a discussion of the interactions between a virus and the immune system, to consider the ultimate outcome. Survivors of CVB infection are sometimes left with sequelae, but for many years it was thought that the virus itself had been eradicated. The picture has changed markedly over the past few years, and it is now clear that the virus (or, at least, some remnants thereof) can persist in the host. The ability of infectious CVB to persist in tissue culture was established some time ago; the virus can institute long-term persistent infection in a variety of cell types, including human myocardial cells [196,197] and human and murine lymphoid cells [198,199]. Infectious virus can be recovered from the supernatants over a period of weeks to months. Tam and Messner have demonstrated that CVB RNA can persist for many months in skeletal muscle in vivo, possibly in the form of a dsRNA complex, and that RNA persistence correlated with the degree of inflammatory infiltration observed [200–202]. However, it is important to note that, in these and most other published studies, infectious virus could not be isolated at the later stages, despite the presence of CVB-related RNA sequences. CVB RNA also has been detected by in situ hybridization in biopsy specimens of human DCM patients, and studies in several mouse strains have shown long-term persistence of CVB-related nucleic acid signal in the heart; the signal was found in several other organs, and is often highly localized, being found near regions of inflammation [203,204]. The identification of CVB RNA long after the primary infection provides several potential explanations for chronic myocarditis: first, viral RNA might trigger innate responses via several pathways (TLRs, RLRs); second, viral protein expression alone can be toxic to cells [205,206]; third, upregulation of viral protein expression could lead to a recrudescent immunopathology mediated by the adaptive immune system; and finally, it is possible that infectious virus may remain, or be sporadically reactivated, thereby causing direct virus-mediated pathology.

Fascinating work by Tracy and colleagues has indicated that variant CVB, lacking several nucleotides from the 5´-end of the genome, may persist in host tissues, undergoing very slow replication; such variants have been reported both in mouse models, and in materials extracted from human heart tissue [207–209]. Thus, in some cases, it seems that CVB and the immune system reach an impasse, in which the cost of eradication (excessive immunopathological damage) may be greater than the cost of permitting the persistence of an agent that is capable of minimal multiplication and spread.

Future perspective

Coxsackieviruses, and their closest relatives, have been honed by the innate and adaptive immune systems and, in turn, presumably have helped to shape these key components of mammalian immunity. In the coming years, the application of proteomics and systems biology will be important in assessing the biological validity of the loop-pathogenesis hypothesis that we present above, and in determining the strength of the proposed mitochondrial link between the cytosolic RNA sensors and the intravesicular nucleic acid-sensing TLRs. The capacity of CVB to remain essentially invisible to naive CD8+ T cells is intriguing, not least because it raises questions about the in vivo effectiveness of antigen cross-presentation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Annette Lord for excellent secretarial support, and to Dr Malcolm R Wood for electron microscopy analyses.

This work was supported by the following NIH grants: R01 AI042314 and HL093177 (J Lindsay Whitton); and F32 AI078660 (Christopher C Kemball). This is manuscript number 20599 from the Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Modlin JF, Rotbart HA. Group B coxsackie disease in children. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1997;223:53–80. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60687-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitton JL. Immunopathology during coxsackievirus infection. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 2002;24:201–213. doi: 10.1007/s00281-002-0100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero JR. Pediatric group B coxsackievirus infections. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;323:223–239. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75546-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connell JB. The role of myocarditis in end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 1987;14:268–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sole MJ, Liu P. Viral myocarditis: a paradigm for understanding the pathogenesis and treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993;22:A99–A105. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90470-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tam PE. Coxsackievirus myocarditis: interplay between virus and host in the pathogenesis of heart disease. Viral Immunol. 2006;19:133–146. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daley AJ, Isaacs D, Dwyer DE, Gilbert GL. A cluster of cases of neonatal coxsackievirus B meningitis and myocarditis. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 1998;34:196–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mena I, Fischer C, Gebhard JR, Perry CM, Harkins S, Whitton JL. Coxsackievirus infection of the pancreas: evaluation of receptor expression, pathogenesis, and immunopathology. Virology. 2000;271:276–288. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber S, Ramsingh AI. Coxsackievirus-induced pancreatitis. Viral Immunol. 2004;17:358–369. doi: 10.1089/vim.2004.17.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuer R, Pagarigan RR, Harkins S, Liu F, Hunziker IP, Whitton JL. Coxsackievirus targets proliferating neuronal progenitor cells in the neonatal CNS. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2434–2444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4517-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beutler B. Microbe sensing, positive feedback loops, and the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2009;227:248–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgel P, Jiang Z, Kunz S, et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G activates a specific antiviral Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. Virology. 2007;362:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triantafilou K, Triantafilou M. Coxsackievirus B4-induced cytokine production in pancreatic cells is mediated through toll-like receptor 4. J. Virol. 2004;78:11313–11320. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11313-11320.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairweather D, Yusung S, Frisancho S, et al. IL-12 receptor β 1 and Toll-like receptor 4 increase IL-1 β- and IL-18-associated myocarditis and coxsackievirus replication. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4731–4737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frisancho-Kiss S, Davis SE, Nyland JF, et al. Cutting edge: cross-regulation by TLR4 and T cell Ig mucin-3 determines sex differences in inflammatory heart disease. J. Immunol. 2007;178:6710–6714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane JR, Neumann DA, Lafond-Walker A, Herskowitz A, Rose NR. LPS promotes CB3-induced myocarditis in resistant B10.A mice. Cell Immunol. 1991;136:219–233. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90396-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richer MJ, Fang D, Shanina I, Horwitz MS. Toll-like receptor 4-induced cytokine production circumvents protection conferred by TGF-β in coxsackievirus-mediated autoimmune myocarditis. Clin. Immunol. 2006;121(3):339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll- like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Negishi H, Osawa T, Ogami K, et al. A critical link between Toll-like receptor 3 and type II interferon signaling pathways in antiviral innate immunity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20446–20451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810372105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinzierl AO, Szalay G, Wolburg H, et al. Effective chemokine secretion by dendritic cells and expansion of cross-presenting CD4−/ CD8+ dendritic cells define a protective phenotype in the mouse model of coxsackievirus myocarditis. J. Virol. 2008;82:8149–8160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00047-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richer MJ, Lavallee DJ, Shanina I, Horwitz MS. Toll-like receptor 3 signaling on macrophages is required for survival following coxsackievirus B4 infection. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:E4127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triantafilou K, Orthopoulos G, Vakakis E, et al. Human cardiac inflammatory responses triggered by coxsackie B viruses are mainly Toll-like receptor (TLR) 8-dependent. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via Toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Xu C, Hsu LC, Luo Y, Xiang R, Chuang TH. A five-amino-acid motif in the undefined region of the TLR8 ectodomain is required for species-specific ligand recognition. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werling D, Jann OC, Offord V, Glass EJ, Coffey TJ. Variation matters: TLR structure and species-specific pathogen recognition. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berdeli A, Celik HA, Ozyurek R, Dogrusoz B, Aydin HH. TLR-2 gene Arg753Gln polymorphism is strongly associated with acute rheumatic fever in children. J. Mol. Med. 2005;83:535–541. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuthill TJ, Bubeck D, Rowlands DJ, Hogle JM. Characterization of early steps in the poliovirus infection process: receptor-decorated liposomes induce conversion of the virus to membrane-anchored entry-intermediate particles. J. Virol. 2006;80:172–180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.172-180.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandenburg B, Lee LY, Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Zhuang X, Hogle JM. Imaging poliovirus entry in live cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:E183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milstone AM, Petrella J, Sanchez MD, Mahmud M, Whitbeck JC, Bergelson JM. Interaction with coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, but not with decay-accelerating factor (DAF), induces A-particle formation in a DAF-binding coxsackievirus B3 isolate. J. Virol. 2005;79:655–660. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.655-660.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coyne CB, Bergelson JM. Virus-induced Abl and Fyn kinase signals permit coxsackievirus entry through epithelial tight junctions. Cell. 2006;124:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coyne CB, Shen L, Turner JR, Bergelson JM. Coxsackievirus entry across epithelial tight junctions requires occludin and the small GTPases Rab34 and Rab5. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel KP, Coyne CB, Bergelson JM. Dynamin- and lipid raft-dependent entry of decay-accelerating factor (DAF)-binding and non-DAF-binding coxsackieviruses into nonpolarized cells. J. Virol. 2009;83:11064–11077. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01016-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang JP, Asher DR, Chan M, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. Cutting edge: antibody-mediated TLR7-dependent recognition of viral RNA. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3363–3367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3363. ▪ Suggests that Type B coxsackieviruses (CVBs) may trigger innate responses in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) only after a humoral response has developed

- 35.Deretic V. Autophagy in infection. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22(2):252–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deretic V, Levine B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:527–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Orvedahl A, Macpherson S, Sumpter R, Jr, Talloczy Z, Zou Z, Levine B. Autophagy protects against sindbis virus infection of the central nervous system. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.007. ▪▪ Thorough and intriguing study of the in vivo effects of autophagy during RNA virus infection

- 38.Lee HK, Lund JM, Ramanathan B, Mizushima N, Iwasaki A. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science. 2007;315:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1136880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delgado MA, Elmaoued RA, Davis AS, Kyei G, Deretic V. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dales S, Eggers HJ, Tamm I, Palade GE. Electron microscopic study of the formation of poliovirus. Virology. 1965;26:379–389. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(65)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlegel A, Giddings TH, Jr, Ladinsky MS, Kirkegaard K. Cellular origin and ultrastructure of membranes induced during poliovirus infection. J. Virol. 1996;70:6576–6588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6576-6588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suhy DA, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. Remodeling the endoplasmic reticulum by poliovirus infection and by individual viral proteins: an autophagy-like origin for virus-induced vesicles. J. Virol. 2000;74:8953–8965. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8953-8965.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor MP, Kirkegaard K. Potential subversion of autophagosomal pathway by picornaviruses. Autophagy. 2008;4:286–289. doi: 10.4161/auto.5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor MP, Kirkegaard K. Modification of cellular autophagy protein LC3 by poliovirus. J. Virol. 2007;81:12543–12553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00755-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harb JM, Burch GE. Spherical aggregates of coxsackie B4 virus particles in mouse pancreas. Beitr. Pathol. 1975;156:122–127. doi: 10.1016/s0005-8165(75)80145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong J, Zhang J, Si X, et al. Autophagosome supports coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J. Virol. 2008;82:9143–9153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoon SY, Ha YE, Choi JE, et al. Coxsackievirus B4 uses autophagy for replication after calpain activation in rat primary neurons. J. Virol. 2008;82:11976–11978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01028-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jackson WT, Giddings TH, Jr, Taylor MP, et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. ▪▪ First paper to show that a virus may not only evade, but may even exploit, the autophagy pathway

- 49.Zhou Z, Jiang X, Liu D, et al. Autophagy is involved in influenza A virus replication. Autophagy. 2009;5:321–328. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sir D, Tian Y, Chen WL, Ann DK, Yen TS, Ou JH. The early autophagic pathway is activated by hepatitis B virus and required for viral DNA replication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4383–4388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911373107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dreux M, Gastaminza P, Wieland SF, Chisari FV. The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14046–14051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907344106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wileman T. Aggresomes and autophagy generate sites for virus replication. Science. 2006;312:875–878. doi: 10.1126/science.1126766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor MP, Jackson WT. Viruses and arrested autophagosome development. Autophagy. 2009;5:870–871. doi: 10.4161/auto.9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor MP, Burgon TB, Kirkegaard K, Jackson WT. Role of microtubules in extracellular release of poliovirus. J. Virol. 2009;83:6599–6609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01819-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gannage M, Dormann D, Albrecht R, et al. Matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus blocks autophagosome fusion with lysosomes. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kyei GB, Dinkins C, Davis AS, et al. Autophagy pathway intersects with HIV-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:255–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Bouteiller O, Merck E, Hasan UA, et al. Recognition of double-stranded RNA by human Toll-like receptor 3 and downstream receptor signaling requires multimerization and an acidic pH. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38133–38145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Paquet ME, Ploegh HL. UNC93B1 delivers nucleotide-sensing Toll-like receptors to endolysosomes. Nature. 2008;452:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature06726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serresi M, Bizzarri R, Cardarelli F, Beltram F. Real-time measurement of endosomal acidification by a novel genetically encoded biosensor. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009;393:1123–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee J, Chuang TH, Redecke V, et al. Molecular basis for the immunostimulatory activity of guanine nucleoside analogs: activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6646–6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Latz E, Schoenemeyer A, Visintin A, et al. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:190–198. doi: 10.1038/ni1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rutz M, Metzger J, Gellert T, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 binds single-stranded CpG-DNA in a sequence- and pH-dependent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:2541–2550. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sepulveda FE, Maschalidi S, Colisson R, et al. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll-like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;31:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Luber CA, Cox J, Lauterbach H, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals subset-specific viral recognition in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;32:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.013. ▪▪ Demonstrates that CD8+ DCs largely lack RIG-I and MDA5, in contrast to most other DCs that express these sensors. The authors suggest that, by delaying activation of an intracellular innate response, the CD8+ DCs may retain the capacity to crosspresent viral antigens, thereby inducing a CD8+ antiviral T-cell response

- 66.Mukherjee A, Morosky SA, Shen L, et al. Retinoic acid-induced gene-1 (RIG-I) associates with the actin cytoskeleton via caspase activation and recruitment domain-dependent interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6486–6494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807547200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. ▪▪ Seminal paper describing how RIG-I and MDA5 sense RNA virus infections

- 68.Loo YM, Fornek J, Crochet N, et al. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J. Virol. 2008;82:335–345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01080-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dixit E, Boulant S, Zhang Y, et al. Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell. 2010;141:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-κB and IRF 3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu LG, Wang YY, Han KJ, Li LY, Zhai Z, Shu HB. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-β signaling. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:727–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]