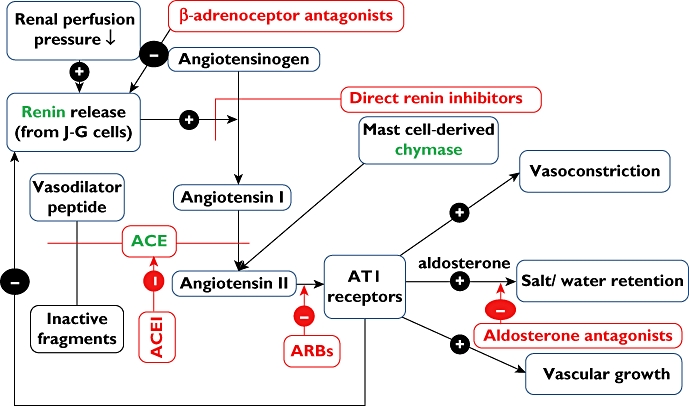

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system can be blocked at one of several points (Figure 1). Simultaneous blockade at more than one point can be therapeutically beneficial, as in the addition of an aldosterone antagonist to an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor in patients with severe heart failure [1] or with left ventricular dysfunction following myocardial infarction [2]. This makes good pharmacological sense, since angiotensin II is not the only stimulus to aldosterone secretion and when the synthesis or action of angiotensin II is blocked the concentration of circulating aldosterone falls initially but then climbs back toward pre-treatment values in some patients (‘aldosterone breakthrough’– see [3]).

Figure 1.

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway and its inhibition by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, AT1 receptor antagonists (ARBs) and other drugs. Note the potential for increased effects of combinations of ACE inhibitors and ARBs via ARB antagonism of non-ACE-derived angiotensin II and potentiation by ACE inhibitors of ACE-inactivated vasodilator peptides. This editors’ view focuses on the divergence between potential effects and what is actually achieved in clinical practice. JG cells = juxta-glomerular cells in renal cortex. (Drugs are shown in red and enzymes in green).

Monotherapy with an ACE inhibitor increases the concentration of circulating angiotensin I because of the loss of feedback inhibition of angiotensin II on renin secretion (Fig 1). Increased substrate (angiotensin I) may partially mitigate inhibition of ACE by a reversible competitive ACE inhibitor, restoring the concentration of active angiotensin II toward pretreatment levels [4,5], This might be termed ‘angiotensin breakthrough’ by analogy with ‘aldosterone breakthrough’, and is one reason why combined blockade by an AT1 receptor antagonist (an angiotensin receptor blocker or ARB) together with an ACE inhibitor might confer added benefit. Additionally, other enzymes distinct from ACE and not blocked by ACE inhibitors can form angiotensin II – for example mast cell-derived chymase [6]. Furthermore, ACE inhibition has pharmacological effects distinct from reducing angiotensin II, notably potentiation of bradykinin in vivo (for example in human resistance forearm vasculature [7]) and possibly also other ACE-inactivated vasodilator peptides (ACE is not substrate-specific for angiotensin I). There are thus several distinct mechanisms by which the combination of an ACE inhibitor (which potentiates vasodilator mechanisms as well as reducing circulating angiotensin II) and an ARB (which blocks AT1 receptor-mediated actions of angiotensin II, whether derived from ACE, chymase or other mechanism) could be qualitatively superior to increasing the dose of either such drug administered as a single agent.

Combined ACE inhibition with AT1 receptor antagonism has a greater effect than monotherapy on blood pressure and on left ventricular hypertrophy (assessed by measurements of heart weight) in spontaneously hypertensive rats [8]. This supported the notion that these drug classes are at least additive and possibly synergistic, which is the basis for a concept of ‘dual blockade’ that is combining ACE inhibition with AT1 receptor antagonism. This strategy has been enthusiastically embraced by prescribers (academics as well as service providers) perhaps because of the seductiveness of the pharmacological rationale outlined above [9, and see below]. However, unlike the addition of aldosterone antagonists to ACE inhibitors [1,2], hard clinical evidence of improved outcomes with of dual blockade with ARBs and ACE inhibitors is weak. A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated an additional effect on blood pressure of around 4/3 mm Hg of the combination versus monotherapy [10]. This begs the question whether an increased dose of monotherapy might have had a similar effect and is modest compared with effects of adding a diuretic or a calcium channel blocker to an ACE inhibitor [see for example 11]. A meta-analysis of effects of combination therapy on albumin excretion (a surrogate marker of glomerular injury) in patients with renal disease did show that dual blockade reduced protein excretion by 20–25% more than monotherapy [12], which was interpreted by many as encouraging evidence in favor of combination treatment. However, while the ONTARGET trial of the combination of telmisartan (ARB) with ramipril (ACE inhibitor) versus monotherapy showed that combined therapy achieved a mean blood pressure reduction 2.4/1.4 mm Hg greater in the combination group than in the group treated with ramipril alone and a greater effect on urinary albumin excretion, the combination showed no benefits in terms of the primary study endpoint (a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke and hospitalisation for heart failure), caused more symptoms attributable to hypotension, and increased the decline in renal function and need for dialysis compared with ACE inhibitor monotherapy[13]. In a trial in patients with myocardial infarction and heart failure there was an increase in adverse events and no survival benefit in patients randomised to combination therapy with valsartan plus captopril [14].

Thus clinical endpoint evidence does not support combined use of ACE inhibitor with ARB, and incidentally also undermines the usefulness of albumin excretion rate as a surrogate marker of renal injury. Messerli concluded that ‘unless data emerge to the contrary, dual blockade should no longer be used in clinical practice’[9]. How has this slow-burning story influenced prescribing of ACE inhibitors and ARBs? In this issue of the Journal [15] Wan and colleagues describe trends in the co-prescription of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in Ireland between January 2000 and April 2009 (> a quarter of a million prescriptions): there has been a significant positive linear trend in co-prescription taking off in 2000–2001 and increasing thirty five-fold (from 0.16 to 5.72 per 1000 eligible population) in the past decade. There was no abrupt discontinuity noticeable following publication of the endpoint trials including COOPERATE (a trial reported in the Lancet in 2003 which purported to show clinical benefit of combination therapy on progression of non-diabetic renal disease but was subsequently retracted by the Lancet editors in 2009), VALIANT and ONTARGET, although a suggestion of a reduction in the rate of increase in co-prescription following publication of ONTARGET in 2008 (see Figure 1 in reference 15). The ‘dual-blockade strategy’ appears to be a juggernaut with considerable momentum, but without a clinical evidence base! What is the cause of these rather striking findings, and what is to be done to improve prescribing in this regard? In this editorial, which supports skeptical criticism of hypotheses (however ingenious and plausible) based on animal models, and increased reliance on clinical rather than surrogate endpoints, we hesitate to speculate as to the cause underlying these prescribing trends but we suspect our readers may be attracted to certain rather obvious possibilities! As regards what is to be done, the answer must surely be through better education in clinical pharmacology and prescribing skills, as we have argued previously [16].

REFERENCES

- 1.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J. Wittes J for the randomized aldactone evaluation study investigators. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J. Gatlin M for the Eplerenone Post–Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1309–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrier RW. Aldosterone ‘escape’ vs ‘breakthrough’. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2010;6:61. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menard J, Guyenne TT, Chatelier G, Kleinbloesem CH, Bernadet P. Renin release regulation during acute renin inhibition in normal volunteers. Hypertension. 1991;18:257–65. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Meiracker AH, Man in't Veld AJ, Admiraal PJ. Partial escape of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition during prolonged ACE inhibitor treatment: does it exist and does it affect the antihypertensive response? J Hypertens. 1992;10:803–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caughey GH. Mast cell tryptases and chymases in inflammation and host defense. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:141–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin N, Cockcroft JR, Collier JG, Dollery CT, Ritter JM, Webb DJ. Local inhibition of converting enzyme and vascular responses to angiotensin and bradykinin in the human forearm. J Physiol. 1989;412:543–55. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menard J, Campbell DJ, Azizi M, Gonzales MF. Synergistic effects of ACE inhibition and Ang II antagonism on blood pressure, cardiac weight and renin in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation. 1997;96:3072–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Messerli FH. The sudden demise of dual renin-angiotensin system blockade or the soft science of the surrogate end point. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.036. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doulton TW, He FJ, MacGregor GA. Systematic review of combined angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin receptor blockade in hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:880–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000161880.59963.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacGregor GA, Markandu ND, Smith SJ, Sagnella GA. Captopril: contrasting effects of adding hydrochlorothiazide, propranolol or nifedipine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(Suppl 11):S82–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunz R, Friedrich C, Wolbers M, Mann JF. Meta-analysis: effect of monotherapy and combination therapy with inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system on proteinuria in renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:30–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The ONTARGET investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, Velasquez EJ, Rouleau J-L, Kober L, Maggioni AP, et al. The valsartan in acute myocardial infarction trial I. Valsartan, captopril or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1839–1906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan AH Wan, Zarahan NL, Bennett K, Wall KA. Trends in co-prescription of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin blockers in Ireland. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:458–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritter JM. Research and education (editors' view) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:1–3. [Google Scholar]