Abstract

This review describes the use of high-throughput flow cytometry for performing multiplexed cell-based and bead-based screens. With the many advances in cell-based analysis and screening, flow cytometry has historically been underutilized as a screening tool largely due to the limitations in handling large numbers of samples. However, there has been a resurgence in the use of flow cytometry due to a combination of innovations around instrumentation and a growing need for cell-based and bead-based applications. The HTFC™ Screening System (IntelliCyt Corporation, Albuquerque, NM) is a novel flow cytometry-based screening platform that incorporates a fast sample-loading technology, HyperCyt®, with a two-laser, six-parameter flow cytometer and powerful data analysis capabilities. The system is capable of running multiplexed screening assays at speeds of up to 40 wells per minute, enabling the processing of a 96- and 384-well plates in as little as 3 and 12 min, respectively. Embedded in the system is HyperView®, a data analysis software package that allows rapid identification of hits from multiplexed high-throughput flow cytometry screening campaigns. In addition, the software is incorporated into a server-based data management platform that enables seamless data accessibility and collaboration across multiple sites. High-throughput flow cytometry using the HyperCyt technology has been applied to numerous assay areas and screening campaigns, including efflux transporters, whole cell and receptor binding assays, functional G-protein-coupled receptor screening, in vitro toxicology, and antibody screening.

Introduction

Cell-Based Screening Has Become an Integral Part of Drug Discovery

Over the last decade, screening compound libraries for their effects in living cells has become an integral and important step in virtually every drug discovery program. This approach grew out of the realization that screening campaigns using biochemical assays, while extremely efficient and compatible with walk-away automated processes, have not lived up to the promise of delivering more effective and safer drugs.1 Screening using cell-based assays has the obvious advantage of testing the effects of compounds against molecular targets within the context of living cells, but also enables broad, systems biology approaches to understanding cellular mechanisms involved in disease processes. Indeed, cell-based screening technologies have enabled drug discovery scientists to develop models of interconnected cellular pathways, extract important information for specific disease models, and build companion diagnostic programs around relevant cellular biomarkers for therapeutics. Automated technologies available for cell-based screening are evolving. From simple cell-based fluorescent, colorimetric, luminescent, and radiologic plate reader assays, to real-time intracellular calcium response measurements and high-content fluorescent imaging systems, the ability to screen compounds against druggable targets in the context of living cells has become essentially routine in both primary and secondary drug-screening programs.

Introduction to High-Throughput Flow Cytometry

The emerging field of high-throughput (HT) flow cytometry is extending the capabilities of cell-based screening technologies. A recent technological breakthrough by Edwards et al.,2,3 known as HyperCyt®, has enabled the use of flow cytometry as a powerful approach for high-throughput screening (HTS) using multiplexed fluorescence intensity assays. The process involves the rapid introduction of multiple samples through a single length of tubing separated by air gaps. The HyperCyt technology involves a change in the sample loading process and is compatible with most modern flow cytometers available today taking full advantage of the capabilities of flow cytometry. With this technology, it is possible to process samples from microplates through flow cytometers at rates of up to 40 wells per minute. This throughput has allowed the implementation of large screening campaigns using assays with multiple readouts per well. Other technologies, such as high-content microscopy, also allow multiple readouts per well making the assessment of an appropriate platform critical to any overall screening goals. When considering a platform for a screening campaign, both the strengths and weaknesses of each should be evaluated. For example, high-throughput flow cytometry is an ideal tool for cell-based applications involving screening suspension cells where multiple readouts are desired. A technique such as high-content microscopy might be utilized in assays using adherent cells where spatial or subcellular information is required. Table 1 generalizes some of the key attributes between high-throughput flow cytometry and high-content microscopy to provide guidelines between these two methodologies. Some of these diverse screening campaigns performed using the HyperCyt technology have included bead-based G-protein-coupled receptor molecular assembly and receptor binding assays,4,5 formylpeptide receptor binding assays,6 drug efflux transporter screens,7 an androgen hormone receptor binding assay,8 and a prostate cancer cell line screen,9 to name a few. In addition to target screening for drug discovery, the ability to utilize flow cytometry in a screening format enables systems biology approaches that can yield critical pathway information.10 There is a growing body of work in this area demonstrating how high-throughput flow cytometry in particular can be used to accomplish such increases in productivity.3,10,11

Table 1.

Comparison of the Key Attributes of High-Throughput Flow Cytometry and High-Content Microscopy

| Key Attributes | HT Flow Cytometry | High Content Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Cell types |

Optimal for suspension cells; adherent cells need to be detached before sampling. |

Optimal for adherent cells; suspension cells need to be immobilized before analysis. |

| Plate requirements |

Standard multiwell round-, v-, or flat-bottom plates can be used. |

Optically clear plastic or glass bottom plates; uniform flat bottom required. |

| Bead assays |

Optimal technique for performing multiplex bead-based assays |

Limited use—beads must be localized to bottom of well. |

| Label-free measurements |

Forward scatter (size) and side scatter (granularity) measurements are standard. |

Brightfield microscopy is offered on some instruments. |

| Cell throughput |

Tens of thousands of cells per second |

Tens to hundreds of cells per second |

| Typical 96-well plate read time |

<5 min; independent of the number of fluorescent parameters |

5–60 min; dependent on the number of fluorescent parameters |

| Dynamic range |

High dynamic range; very faint to very bright signals can be detected in the same sample. |

Lower dynamic range |

| Spatial measurements |

No |

Yes |

| Typical data file size | 1 to 100 MB per plate | 100 to 1,000 MB per plate |

The Power of Flow Cytometry as a HTS Tool

What Is Flow Cytometry?

Flow cytometry is a well-established technology that has been widely used in many disciplines for measuring intrinsic properties of cells, such as the size and subcellular structures. Also, extrinsic properties based upon fluorescent biochemical labels can be used to look at a variety of cellular features such as protein binding, metabolic activities, or DNA content. In order to use flow cytometry to make such measurements, the samples and target particles must be suspended, which is ideal for cells that are in suspension in their native state, for example, blood cells, but may require additional steps such as trypsinization when working with adherent cells.9 The extent of any preparation steps will be assay-dependent and should be evaluated during the assay development process. Cells or other particles in liquid suspension, ranging in sizes from <1 μm to >25 μm, are introduced into a moving focused stream that is interrogated by one or more lasers, and the resultant fluorescence or scattered laser light is captured by an optical detector and quantified. Only the fluorescence that is associated with the labeled particles is measured, so that background fluorescence in the fluid goes undetected. Multiple fluorescence measurements can be made simultaneously on a per cell basis by a series of photomultiplier tubes equipped with fluorochrome-specific optical filters that collect the emitted fluorescence and correlate the intensity with the specific particle that passed through the laser beam. Additionally, the amount of laser light that is scattered by the particle is also measured—giving indications as to the relative cell size and membrane integrity when captured in line with the incident light source (forward scattered light), and indicating the amount of subcellular complexity or granularity when captured at a 90° angle (side scatter). All of the data collected by the detectors/photomultiplier tubes are correlated with each particle detected and stored in a list mode file of the sampled suspension. Flow cytometry analysis software is used to display results for each measured parameter on each cell or particle and is used to make correlations between any of the fluorescent markers, the cell size, subcellular structure, or a combination of these parameters, allowing the identification of subpopulations within the sample. Modern flow cytometers are typically equipped with two or more lasers and detection capabilities for six or more detectors with the ability to measure 10,000 or more particles/second. This ability to make numerous simultaneous and sensitive measurements in a given sample provides the opportunity to conduct experiments wherein many biomarkers or cellular characteristics can be measured on living cells and provide a more thorough investigation into the effects of chemical or biological agents on cellular function.12

Multiplexing with Flow Cytometry

One of the most important aspects of flow cytometry is the ability to perform multiple analyses on each cell or particle in a sample, known more commonly as multiplexing. The idea of multiplexing is fairly straightforward wherein different types of particles (e.g., cells or beads) containing multiple fluorescent tags, are analyzed together in the same sample. One important advantage provided by multiplexing is the immediate gain in productivity, where, for example, the use of two or more fluorescent endpoints in one flow assay is equivalent to running two or more separate experiments on a plate reader. To this end, the gains in productivity and information per sample can be exponential.

A number of multiplexing strategies have been put into practice. A simple example might include the combination of a fluorescent receptor binding readout with cell counts and a cell viability indicator. A more complex example might involve the assessment of binding events between multiple targets on individual cells, with each binding event detected by a different color fluorescent marker. This has been taken to an extreme where, in an immunological proof of concept study, as many as 19 separate parameters were analyzed in a single sample by using various cell-surface markers and intracellular cytokine tags.13 Another powerful multiplexing approach is to identify different populations within a sample by prelabeling each population with a different color fluorescent marker and then combining them into a single sample. In fact, there are an increasing number of labs interested in pushing the limits in tagging cells this way, also termed “barcoding,” which aims to uniquely label many populations of cells separately, combine them, and then deconvolve each population using analysis software.14 Finally, while there are many ways to multiplex cell-based assays, there are enormous multiplexing capabilities in using bead-based technologies, which can allow for 100-plex, and more recently 500-plex, assays in a bead-based ELISA format.15,16

Multiplexing provides tangible gains in productivity by simultaneously measuring multiple assay endpoints. In addition to gains in productivity, multiplexing can be applied to detailed population analyses on samples containing mixed populations. Using cell type-specific fluorescent probes, it is possible to identify the subpopulations within a given sample and then query those subpopulations for further information. To illustrate this point, an assay can be constructed that first identifies actively dividing cells and then measures expression of a specific surface receptor protein within that subpopulation. In another example, lymphocyte subsets can be specifically labeled with fluorescent markers, and then queried for expression of cell signaling proteins. In these examples, not only are there multiple endpoints of information within one sample, but also differences within the sample can be exposed.

IntelliCyt HTFCTM Screening System

Overview of the IntelliCyt HTFC Screening System

The IntelliCyt HTFC Screening System (Fig. 1) (IntelliCyt Corporation, Albuquerque, NM) brings together the analysis attributes of flow cytometry, HTS, and a powerful data analysis and management system into one platform. The system uses HyperCyt sampling technology (described below) and is capable of processing plates containing cells and/or beads at rates of 40 wells per minute. The HTFC Screening System flow cytometer utilizes a red and a blue laser, and can analyze six separate parameters over a six-decade dynamic range in each well. A key component of the HTFC Screening System is the HyperView® data analysis software, which guides users through an intuitive, step-by-step process for extracting hits and trends from plate level data.

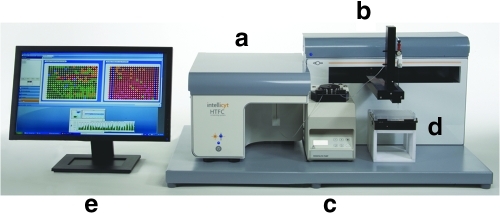

Fig. 1.

The HTFC Screening System (IntelliCyt Corporation). (a) 2-laser, 4-color flow cytometer; (b) an x, y, z autosampler; (c) a low pulsation peristaltic pump; (d) orbital plate shaker that accommodates 96- and 384-well plates; (e) system computer with HyperView installed to set up experiments and process plate data.

HyperCyt Technology

The HTFC Screening System incorporates the HyperCyt sample transfer technology. This is a patented automated sample loading method in which multiple samples are aspirated from multiwell plates, and delivered directly into the flow cell of a flow cytometer. 17–21 The method involves the sequential extraction of samples from the wells into a single length of transfer tubing, with the samples being separated one from another by air gaps (Fig. 2). The stream of samples from the entire plate is delivered directly into the flow cell of the cytometer. The HyperCyt method has been used to perform high-throughput flow cytometry screening campaigns at sampling speeds of 40 wells per minute. This equates to sampling times of 3 min for a 96-well plate and 12 min for a 384-well plate. A key attribute of the HyperCyt method is that the sample tubing is primed once with buffer before the samples are taken up into the tubing so that only the amount of sample that will be analyzed is removed from the well. This enables two important features: (i) very small volumes—as low as 1 μL—can be sampled and analyzed from each well, and (ii) the entire contents of each well can be extracted and analyzed without sacrificing sample due to tubing and/or reservoir dead volume.

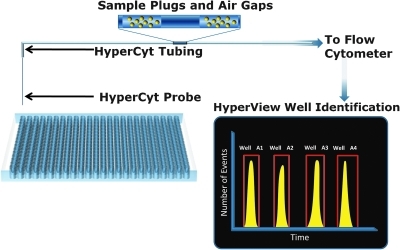

Fig. 2.

Depiction of the HyperCyt sampling process. The HTFC Screening System utilizes a low pulsation peristaltic pump to transfer samples from microplates into the flow cytometer via the sample tubing. Samples are separated one from another by air gaps. The stream of samples and air gaps traverse the tubing to the flow cell of the cytometer for detection. The cytometer collects data continuously resulting in a time-resolved histogram, which is graphically shown. HyperView software deconvolves this data formatting it in to a plate layout.

High-Throughput Flow Cytometry Data Analysis

The HTFC Screening System utilizes the data analysis capabilities of HyperView, a software package designed for high-throughput flow cytometry screening. HyperView takes the user through a step-by-step process to identify populations of interest and automatically generates well statistics for each population/parameter combination. An important feature of the HTFC Screening System is the ability to capture the raw plate data from the stream of air gap-separated samples as one flow cytometry standard (FCS) data file. Using HyperView, data from the entire plate is processed simultaneously, significantly streamlining the data analysis workflow and allowing users to quickly analyze large numbers of plates and identify hits from screening runs.

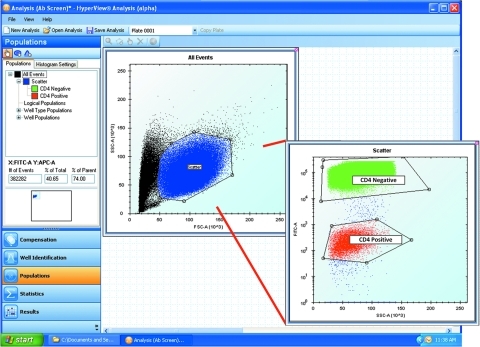

Multiplexed Antibody-Screening Application

To illustrate the HyperView data analysis process, each step of the analysis workflow is discussed below using a multiplex high-throughput flow cytometry screening application as an example. In this application, a duplex screening assay was developed to detect antibodies that bind specifically to CD4 on the surface of target cells but not to control cells that were CD4 negative (Fig. 3). The assay was developed to screen a hybridoma library generated by immunizing mice with a cell line expressing CD4. The assay achieves two important cell-based screening goals: (i) since the target binding protein was assayed in the context of living cell membranes, it maintains its natural conformation, and (ii) both target cells and control cells were present and analyzed in every well of the plates, combining a specificity and cross reactivity screen into one run. The assay protocol involved prelabeling the control cell line with a green indicator dye, Calcein AM, whereas the target cell line was left unstained. Both cell lines were distributed into the wells of assay plates, and then incubated with supernatants from the hybridoma library. Antibodies from the hybridomas bound to the cells were quantified in each well of the screening plates by using a detection antibody labeled with APC, which fluoresces in the red channel. The plates were processed through the HTFC Screening System, and data were analyzed using HyperView. With this system, twenty or more 384-well plates can easily be processed per day.

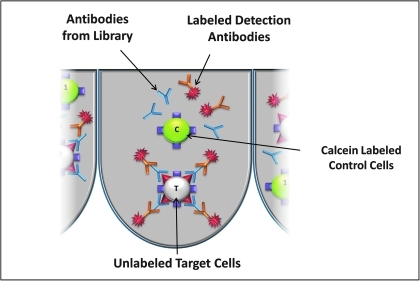

Fig. 3.

Application example illustrating a multiplex antibody detection screen to highlight how HyperView software is used. The experiments used mixtures of cell lines, which either expressed human CD4 or did not. Screening for antibodies in a hybridoma library that specifically bind to CD4 were assessed by monitoring both populations of cells simultaneously on the flow cytometer.

Plate Data Processing

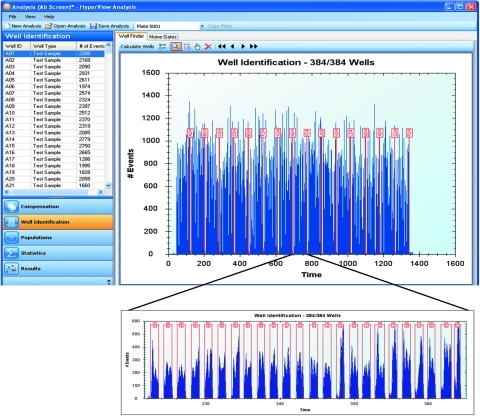

As described above, the HTFC Screening System collects data from all of the wells of each plate into one file. The Well Identification feature in HyperView automatically segments the data file into individual wells associated with each plate in the screening run (Fig. 4). The Well Identification algorithm utilizes experimental parameters such as sampling order, sampling time, inter-well rinsing and shaking, the height and event counts of peaks, and the spacing between them in order identify the individual wells. This process allows the single FCS data file associated with the entire plate to be addressed into individual well data to track statistics and populations for each well of the plate. If needed, each well can be analyzed in detail and exported as a separate data file.

Fig. 4.

Screenshot from HyperView showing an example of the Well Identification process. Data from the 384-well plate is collected in to a single flow cytometry standard file, which is shown in the main window. The data are deconvolved by the software algorithm to identify each peak with a well address on the plate. One row is expanded to show temporally spaced individual peaks.

Identifying Populations

Perhaps the most powerful feature of high-throughput flow cytometry is the ability to analyze multiple populations within each well of every assay plate. In HyperView, this is accomplished within the Populations tab (Fig. 5), which enables the user to create a hierarchical tree of populations based on fluorescent and scattered light properties associated with each cell in the data set. A workspace displays populations in the left window pane and a virtual desktop on the right. Multiple one- and two-dimensional histograms can be displayed and processed. After the desired histograms are generated, electronic gates are drawn around the subpopulations of interest and each population is identified, named, and color coded. For example, Figure 5 shows a screenshot from an analysis of the multiplex hybridoma screening assay described above. All of the cells from the plate are displayed in the histograms. Using the gating tools, a primary gate was drawn around the major cell population and color coded blue (separated from smaller cell debris in black) in a dot plot of side scatter versus forward scatter. Within this population, two subpopulations can be identified based on the fact that the CD4-negative cells were prestained with Calcein AM, a cellular dye that fluoresces in the green channel of the instrument (color coded green). The CD4-positive cell population, color coded red, has a lower intensity green fluorescence. Combined with the Well Identification process, cells in each of the gated populations are automatically assigned to the appropriate well address allowing for subpopulation statistics per well to be rapidly generated.

Fig. 5.

Screenshot of HyperView software. On the left window pane are the populations and histogram settings above the workflow process tabs. In this example, the Well Identification process has been completed and analysis of the populations is being shown. On the right side of the screen is the virtual desktop that accommodates many plots at the same time for ease of data viewing. A miniature version of the virtual desktop is shown in the middle of the left window pane.

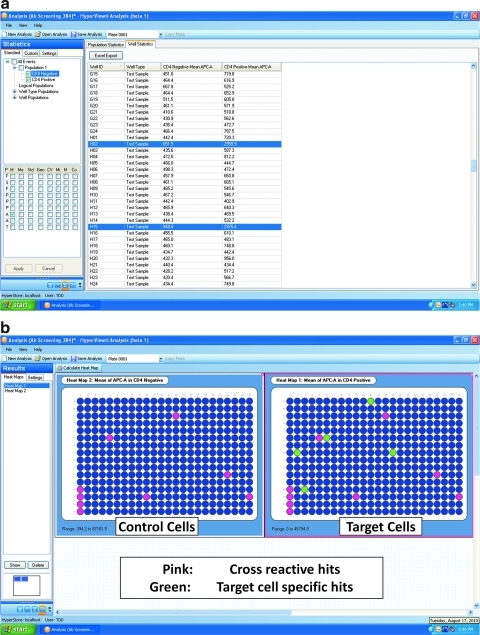

Generating Statistics and Identifying Hits

The Statistics tab presents data for each well of the microplate in tabular format. Any combination of cytometric parameters and statistical measurements (Fig. 6a) can be displayed in the statistics spreadsheet, and if needed, the data can be exported as a comma separated values file for further analysis. Each well of the plate is indicated on the left side of the spreadsheet, and each column reports a statistic/parameter/population combination. For example, in Figure 6a, antibody binding, as indicated by median red (APC) fluorescence values associated with cells in the CD4-negative and CD4-positive populations, respectively, is shown for each well of the plate in the hybridoma screening assay example.

Fig. 6.

Statistics results and heat maps from HyperView. (a) The statistics window shows selected parameters for each population of events identified in the Populations tab. For all channels, a number of statistical parameters can be selected. Two of the rows are highlighted to show how potential binding hits would appear. (b) Heat maps are shown from the hybridoma screening experiment described in the text. The blue color indicates low antibody binding and pink/red/green represent high antibody binding. In this example, both CD4-positive and CD4-negative cells are in each well. Specific hits for CD4 binding are represented by wells that have signal in the CD4-positive map (green) but not in the CD4-negative or control cells map (red/pink).

On the Results page, color-coded heat maps can be generated to quickly and visually identify hits within plates of a screen (Fig. 6b). The heat map function generates well level data for each population/parameter/statistic combination in a color-coded plate layout format. In Figure 6b, two heat maps are shown, with the blue color representing a low signal and the pink/red/green colors representing a high signal. Both heat maps display antibody binding (median red [APC] fluorescence) associated with cells from each well. Heat Map 2 (CD4 Negative) displays the control cell population, whereas Heat Map 1 (CD4 Positive) displays the target cell population. By comparing the colors of the two populations, wells which contain antibodies that bind specifically to the target cells and not to the control cells are quickly identified. In this case, green was used to highlight true binding hits, or wells that showed binding on the CD4 positive plate but not the CD4 negative plate (Fig. 6b). Note that Figure 6a has two of these hits highlighted within the well statistics spreadsheet. The visual attributes of the heat maps are fully configurable by the user, including color scheme and values assigned to each color level.

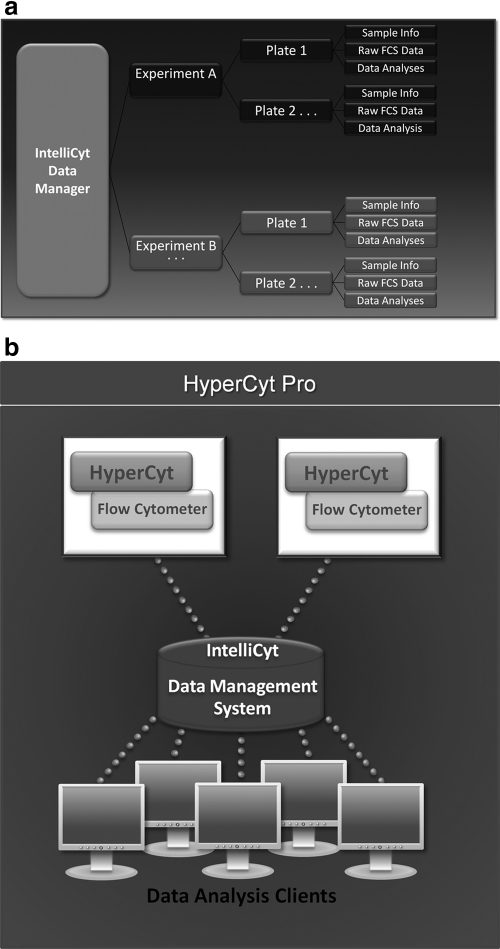

Intellicyt HTFC Data Management System

Embedded in the HTFC Screening System is the IntelliCyt Data Manager (iDM™), which allows users to easily manage their high-throughput flow cytometry screening data. iDM runs in the background to keep track of all of the data associated with a screening campaign. The system uses a centralized server, which consolidates and stores the experimental design, sampling information, user information, analyses, and data files associated with all of the plates in a screen indexed as an “Experiment.” Users can then access all data associated with their screens by simply retrieving an Experiment within HyperView.

Figure 7 outlines the iDM information path. Experiments (designated “A” and “B” in Fig. 7) include sample data and metadata for all of the plates in the screen. “Attached” to each plate are the user information, experimental parameters, and the raw FCS data. Thus, by knowing the Experiment name of a specific high-throughput screen, users have instant access to every piece of information associated with that screen. This enables users to evaluate and track different analysis strategies for their screening runs. For example, a user may wish to evaluate the effects of different gate sets on hit-rate in a screen. This is easily managed in HyperView, since each analysis can be saved separately without compromising the results obtained in the other analyses of the same screen. In the end, all of the analyses, experimental parameters, plate information, and other relevant documents can be saved and organized under each plate.

Fig. 7.

Schematic of the iDM platform. iDM functions on two levels. (a) The iDM system tracks raw data, experimental parameters, sample information, and analyses from each plate and associates it with an experiment. (b) The system coordinates multiple HTFC Screening Systems and HyperView clients, allowing the data from each system to be accessed by multiple researchers. iDM, IntelliCyt Data Manager.

Because the iDM platform utilizes a centralized server to manage data, it is a robust collaboration tool for high-throughput flow cytometry screening campaigns. While the actual screening and data acquisition occurs at the HTFC Screening System workstation, client computers running HyperView can be used to design experiments and analyze data. This allows multiple users simultaneous access to their screen data without tying up the HTFC screening workstation. This also enables multiple team members to review the screening data, without having to physically transfer data files. Collaboration management is also possible, which enables the establishment of teams of scientists, with multiple levels of permissions, to access the data. Finally, the system is completely scalable such that multiple HTFC Screening System workstations and HyperView clients can be operated through the iDM system, even across multiple geographic locations.

Conclusion

The use of cell-based screening technologies has become an integral component of drug discovery. The advancement of cell-based assays has enabled a better understanding of the interconnectedness of cellular pathways, a chance to focus on developing models for specific disease states, and the ability to explore relevant cellular biomarkers for therapeutics. With the advancement of high-throughput flow cytometry a new tool can be added to the arsenal of cell-based screening technologies. The HTFC Screening System discussed in this review is a platform that facilitates high-throughput flow cytometry screening in 96- and 384-well plate formats. Incorporating flow cytometry into cell-based screening campaigns enables the use of multiplexed assays, thus effectively running multiple assays in each well. Because high-throughput flow cytometry is the preferred technology for analyzing particles in suspension, it is an ideal technology for screening assays that utilize nonadherent cells such as cells representing the immune system, microorganisms, or multiplexed bead arrays. Multiplexed screening assays can increase productivity, while providing a more thorough understanding of the complex effects of potential therapeutics.

Abbreviations

- FCS

flow cytometry standard

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- iDM

IntelliCyt Data Manager

Disclosure Statement

All authors are employees of IntelliCyt Corporation.

References

- 1.Feng Y. Mitchison TJ. Bender A. Young DW. Tallarico JA. Multi-parameter phenotypic profiling: using cellular effects to characterize small-molecule compounds. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:567–578. doi: 10.1038/nrd2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards BS. Kuckuck FW. Prossnitz ER. Ransom JT. Sklar LA. HTPS flow cytometry: a novel platform for automated high throughput drug discovery and characterization. J Biomol Screen. 2001;6:83–90. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BS. Young SM. Saunders MJ. Bologa C. Oprea TI. Ye RD. Prossnitz ER. Graves SW. Sklar LA. High-throughput flow cytometry for drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2007;2:685–696. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman DL. Talbot JN. Roof RA. Sunahara RK. Traynor JR. Neubig RR. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of RGS4 using a high-throughput flow cytometry protein interaction assay. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:169–175. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons PC. Shi M. Foutz T. Cimino DF. Lewis J. Buranda T. Lim W. Neubig RR. McIntire WE. Garrison J. Prossnitz E. Sklar LA. Ligand–receptor–G-protein molecular assemblies on beads for mechanistic studies and screening by flow cytometry. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1227–1238. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards BS. Bologa C. Young SM. Balakin KV. Prossnitz ER. Savchuck NP. Sklar LA. Oprea TI. Integration of virtual screening with high-throughput flow cytometry to identify novel small molecule formylpeptide receptor antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1301–1310. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivnitski-Steele I. Larson RS. Lovato DM. Khawaja HM. Winter SS. Oprea TI. Sklar LA. Edwards BS. High-throughput flow cytometry to detect selective inhibitors of ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 transporters. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2008;6:263–276. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis MK. Bowles HJC. MacKenzie DA. Burchiel SW. Edwards BS. Sklar LA. Prossnitz ER. Todd TA. A multifunctional androgen receptor screening assay using the high-throughput HyperCyt® flow cytometry system. Cytometry A. 2008;73A:390–399. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haynes MK. Strouse JJ. Waller A. Leitao A. Curpan RF. Bologa C. Oprea TI. Prossnitz ER. Edwards BS. Sklar LA. Thompson TA. Detection of intracellular granularity induction in prostate cancer cell lines by small molecules using the HyperCyt® high-throughput flow cytometry system. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:596–609. doi: 10.1177/1087057109335671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan JP. Yang L. The flow of cytometry into systems biology. Brief Funct Genomics Proteomics. 2007;6:81–90. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peluso J. Tabaka-Moreira H. Taquet N. Dumont S. Reimund J-M. Muller CD. Can flow cytometry play a part in cell based high-content screening? Cytometry A. 2007;71A:901–904. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro HM. Practical Flow Cytometry. 4th. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perfetto SP. Chattopadhyay PK. Roederer M. Seventeen-colour flow cytometry: unravelling the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:648–655. doi: 10.1038/nri1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krutzik PO. Nolan GP. Fluorescent cell barcoding in flow cytometry allows high-throughput drug screening and signaling profiling. Nat Methods. 2006;3:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nmeth872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwenk JM. Lindberg J. Sundberg M. Uhlén M. Nilsson P. Determination of binding specificities in highly multiplexed bead-based assays for antibody proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:125–132. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T600035-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishhanabc VV. Khancd IH. Luciw PA. Multiplexed microbead immunoassays by flow cytometry for molecular profiling: basic concepts and proteomics applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2009;29:29–43. doi: 10.1080/07388550802688847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez S. Aiken CT. Andrzejewski B. Sklar LA. Edwards BS. High-throughput flow cytometry: validation in microvolume bioassays. Cytometry A. 2003;53:55–65. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards BS. Kuckuck FW. Prossnitz ER. Okun A. Ransom JT. Sklar LA. Plug flow cytometry extends analytical capabilities in cell adhesion and receptor pharmacology. Cytometry A. 2001;43:211–216. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20010301)43:3<211::aid-cyto1052>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sklar LA. Edwards BS. Kuckuck FW. Flow cytometry for high throughput screening. U.S. patent #6,890,487. 2005 May 10;

- 20.Sklar LA. Edwards BS. Kuckuck FW. Flow cytometry for high throughput screening. U.S. patent #6,878,556. 2005 Apr 12;

- 21.Sklar LA. Edwards BS. Kuckuck FW. Flow cytometry for high throughput screening. U.S. patent #7,368,084. 2008 May 6;