Abstract

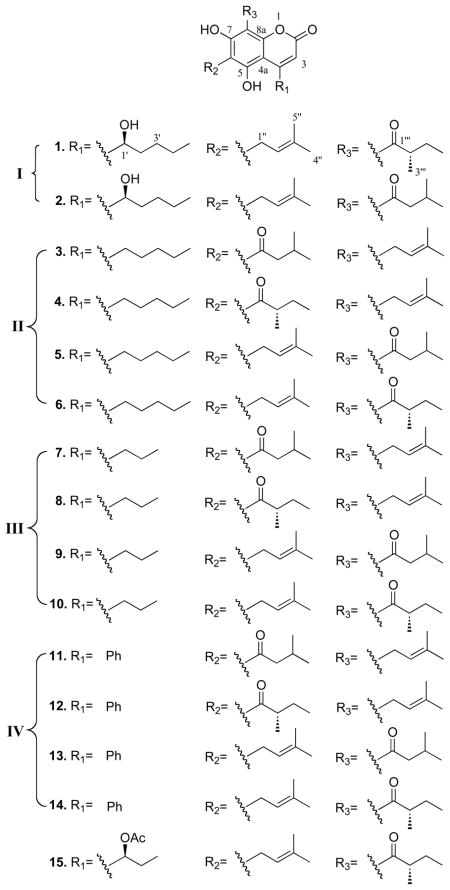

In an effort to identify natural product-based molecular-targeted antitumor agents, mammea-type coumarins from the tropical/subtropical plant Mammea americana were found to inhibit the activation of HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor-1) in human breast and prostate tumor cells. In addition to the recently reported mammea E/BB (15), bioassay-guided fractionation of the active extract yielded fourteen mammea-type coumarins including three new compounds mammea F/BB 1 (1), mammea F/BA (2), and C/AA (3). The absolute configuration of C-1′ in 1 was determined by the modified Mosher’s method on a methylated derivative. These coumarins were evaluated for their effects on mitochondrial respiration, HIF-1 signaling, and tumor cell proliferation/viability. Acetylation of 1 afforded a triacetoxylated product (A-2) that inhibited HIF-1 activation with increased potency in both T47D (IC50 0.83 μM for hypoxia-induced) and PC3 cells (IC50 0.94 μM for hypoxia-induced). Coumarins possessing a 6-prenyl-8-(3-methyl-oxobutyl)-substituent pattern exhibited enhanced HIF-1 inhibitory effects. The O-methylated derivatives were less active at inhibiting HIF-1 and suppressing cell proliferation/viability. Mechanistic studies indicate that these compounds act as anionic protonophores that potently uncouple mitochondrial electron transport and disrupt hypoxic signaling.

Advanced solid tumors are typically characterized by the presence of hypoxic (reduced oxygen tension) regions.1 The transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) acts as a major regulator of cellular adaptation and survival under hypoxic conditions. In non-transformed normal cells, HIF-1 is inactive due to the rapid degradation of the oxygen-sensitive HIF-1α subunit by the ubiquitin-protesome pathway.2 In tumor cells, hypoxia, the activation of oncogene(s), and/or the inactivation of tumor suppressor gene(s) can each activate HIF-1.2 Extensive preclinical and clinical studies support HIF-1 as a major molecular target for hypoxia-selective anticancer drug discovery.2 A number of agents that inhibit HIF-1 have entered clinical trials in the U.S. for cancer (HIF-1A RNA antagonist EZN2968, HIF-1A expression inhibitor PX-478, and low-dose HIF-suppressive regimens of the topoisomerase inhibitor topotecan).3

Natural products have been and are continuing to be a major source of new anticancer agents.4 Our research has focused on the discovery of small-molecule HIF-1 inhibitors from natural sources.5 Over 15000 samples from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Open Repository of terrestrial plant lipid extracts were evaluated for HIF-1 inhibitory activity. In a human prostate carcinoma PC3 cell-based reporter assay, a lipid extract of the plant Mammea americana L. (Guttiferae/Clusiaceae) inhibited hypoxia (1% O2)-induced HIF-1 activation by 89% at 5 μg/mL. Bioassay-guided isolation and structure elucidation of the active extract (4.1 g) afforded three new mammea-type coumarins (1 – 3) and twelve previously reported analogues (4 – 15).6–10

The mammea-type coumarins have been reported to exhibit a wide spectrum of biological activities that range from antimicrobial,9 cytostatic/cytotoxic to tumor cells,7,10 to radical-scavenging activities.8 Mammea E/BB (15) has recently been shown to inhibit HIF-1 activation by uncoupling the mitochondrial electron transport chain and disrupting mitochondrial signaling.10 This report describes the identification and characterization of bioactive constituents of M. americana, and examines structure-activity relationships of natural and semisynthetic mammea-type coumarins on mitochondrial respiration and HIF-1-mediated hypoxic signaling in human tumor cell lines.

Results and Discussion

Compound 1 was obtained as an optically active pale brown oil. Its molecular formula, C24H32O6, was established by HRESIMS, indicating nine degrees of unsaturation. Two absorption maxima bands at 254 nm (log ε 3.85) and 328 nm (log ε 4.31) in the UV spectrum were characteristic for a coumarin.11 The IR spectrum showed the presence of carbonyl (νmax 1709) and hydroxy (νmax 3306) groups. The 1H NMR spectrum displayed five methyl resonances, including two triplets (δH 0.89 and 0.91), a doublet (δH 1.17), and two singlet resonances (δH 1.66 and 1.77). Three oxygenated or olefinic protons were observed at δH 4.70, 5.19, and 6.02, and eleven upfield protons were ascribed to methines or methylenes. Two especially downfield singlet resonances at δH 11.6 and 14.2 indicated the presence of two H-bonded hydroxy protons. The 13C NMR spectrum displayed 24 carbons. Analysis of the HMQC spectrum allowed the carbon resonances to be ascribed to five methyl groups (δC 11.7, 13.9, 16.7, 18.0, and 25.9), an oxygenated methine (δC 76.5), two olefinic methines (δC 108.5 and 121.6), five methylenes, a methine resonance, a ketone carbonyl carbon (δC 210.3), and ten quaternary carbons (Table 1).

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR Data of 1 – 3 (400 and 100 MHz, CDCl3, δ ppm).

| position | 1 |

2 |

3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) | δC | |

| 2 | 160.6, C | 160.9, C | 160.6, C | |||

| 3 | 6.02, s | 108.5, CH | 5.95, s | 108.7, CH | 5.93, s | 110.0, CH |

| 4 | 157.4, C | 157.3, C | 160.3, C | |||

| 4α | 101.1, C | 100.9, C | 103.6, C | |||

| 5 | 158.1, C | 157.9, C | 163.9, C | |||

| 6 | 114.5, C | 114.9, C | 107.2, C | |||

| 7 | 166.5, C | 166.9, C | 160.1, C | |||

| 8 | 104.0, C | 104.1, C | 105.1, C | |||

| 8a | 156.2, C | 156.3, C | 157.5, C | |||

| 1′ | 4.70, t (6.4) | 76.5, CH | 4.67, t (6.7) | 76.9, CH | 2.95, t (7.6) | 36.7, CH2 |

| 2′ | 1.93, m 1.66, m |

34.4, CH2 | 1.94, m 1.67, m |

34.1, CH2 | 1.60, m | 29.4, CH2 |

| 3′ | 1.48, m 1.32, m |

28.2, CH2 | 1.47, m 1.35, m |

28.1, CH2 | 1.38, m | 31.9, CH2 |

| 4′ | 1.32 m | 22.4, CH2 | 1.35 m | 22.1, CH2 | 1.34 m | 22.6, CH2 |

| 5′ | 0.89, t (7.2) | 13.9, CH3 | 0.89, t (7.1) | 14.0, CH3 | 0.89, t (7.0) | 14.1, CH3 |

| 1″ | 3.35, d (6.2) | 22.2, CH2 | 3.34, t (6.9) | 22.8, CH2 | 207.6, C | |

| 2″ | 5.19, t (6.2) | 121.6, CH | 5.17, t (6.9) | 121.5, CH | 3.00, d (6.7) | 53.6, CH2 |

| 3″ | 133.0, C | 133.0, C | 2.26, m | 25.1, CH2 | ||

| 4″ | 1.66, s | 25.9, CH3 | 1.67, s | 25.9, CH3 | 0.96, d (6.7) | 22.9, CH3 |

| 5″ | 1.77, s | 18.0, CH3 | 1.79, s | 18.0, CH3 | 0.96, d (6.7) | 22.9, CH3 |

| 1‴ | 210.3, C | 205.1, C | 3.55, d (6.9) | 22.0, CH2 | ||

| 2‴ | 3.67, m | 47.1, CH | 2.97, dd (6.9, 15.6) 2.80, dd (6.9, 15.6) |

53.8, CH2 | 5.19, t (6.9) | 120.4, CH |

| 3‴ | 1.17, d (6.6) | 16.7, CH3 | 2.16, m | 25.3, CH2 | 137.9, C | |

| 4‴ | 1.80, m 1.37, m |

27.1, CH2 | 0.96, d (7.4) | 22.4, CH3 | 1.78, s | 26.0, CH3 |

| 5‴ | 0.91, t (7.4) | 11.7, CH3 | 0.98, d (7.4) | 22.7, CH3 | 1.85, s | 18.2, CH3 |

| OH-7 | 14.20, s | 14.37, s | ||||

| OH-5 | 11.60 br, s | 11.57 br, s | ||||

| OH | 15.15 br, s | |||||

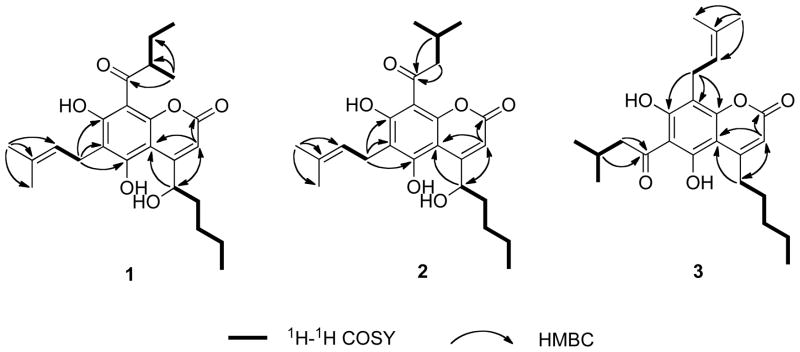

Three partial structures of 1 were deduced from interpretation of the spectroscopic data. The presence of a hydroxypentyl moiety (Figure 1) was established by observation of a proton spin system between the methyl resonance at δH 0.89 t (CH3-5′) and the oxygenated methine resonance at δH 4.70 (H-1′) in the 1H-1H COSY spectrum. The presence of a prenyl unit was confirmed by 1H-13C HMBC correlations from the methyl resonance at δH 1.66 s (C-4″) to the carbon resonances at δC 121.6 (C-2″), 133.0 (C-3″), and 18.0 (C-5″). The 1H-1H COSY spectrum displayed a correlation between 2H-1″ (δH 3.35) and H-2″ (δH 5.19) (Figure 1). Additionally, the 1H-1H COSY correlations between CH3-3‴ (δH 1.17), H-2‴ (δH 3.67), 2H-4‴ (δH 1.37 and 1.80), and CH3-5‴ (δH 0.91), together with the HMBC correlations from CH3-3‴ (δH 1.17) to C-2‴ (δC 47.1), C-4‴ (δC 27.1), and a ketone carbonyl carbon resonance at δC 210.3 suggested the occurence of a 2-methyl-oxobutyl substitution (Figure 1). Chemical shift analysis of the remaining nine carbons with those previously reported,6–9,12 indicated that 1 is a typical mammea-type 5,7-dihydroxycoumarin. The hydroxypentyl moiety was deduced as being attached to C-4 (δC 157.4) by observation of HMBC correlations from H-1′ (δH 4.70) to C-3 (δC 108.5) and C-4a (δC 101.1), as well as from H-3 (δH 6.02) to C-4a (δC 101.1), C-1′ (δC 76.5), and C-1 (δC 160.6) (Figure 1). In order to determine the substitution pattern of the prenyl and 2-methyl-oxobutyl substituents, the chemical shifts of C-6 and C-8 were compared with the published values reported for those of 6-acyl-8-prenyl and 6-prenyl-8-acyl-substituted analogues.6–9,12 In the 6-prenyl-8-acyl-substituted analogues, C-6 was significantly downfield relative to C-8 (δ ~5–10 ppm, CDCl3), while the observed chemical shift difference was only about 2 ppm in the 6-acyl-8-prenyl-substituted analogues. The 2H-1″ (δH 3.35) proton resonance was correlated in the HMBC spectrum with C-5 (δC 158.1), C-6 (δC 114.5), and C-7 (δC 166.5) (Figure 1). Further, C-6 was significantly more downfield relative to C-8 (Δδ10.5 ppm, Table 1). Thus, the prenyl and 2-methyl-oxobutyl moieties were placed at C-6 and C-8, respectively. Therefore, the planar structure of 1 was deduced as 5,7-dihydroxy-4-(1-hydroxypentyl)-6-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)-8-(2-methylbutanoyl)-2H-chrome n-2-one.

Figure 1.

Selected 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 1 – 3.

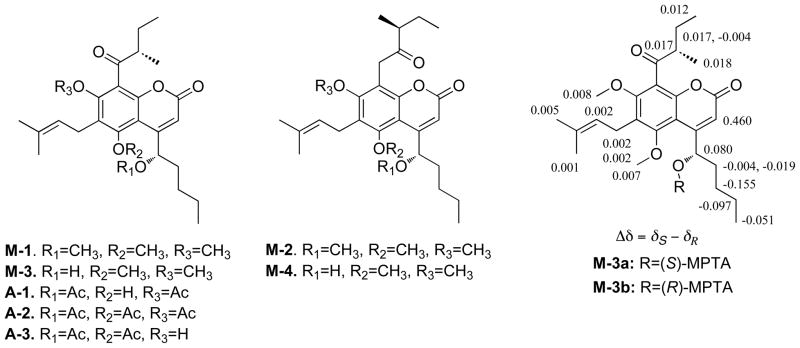

Compound 1 was subjected to methylation with diazomethane in MeOH, producing four products, M-1, M-2, M-3, and M-4. The methylated product, M-1 (molecular formula C27H38O6) displayed three methoxy resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum and was determined to be a tri-O-methylated derivative of 1. Another trimethylated product, M-2, was found to possess an additional -CH2- unit in the molecular formula relative to the formula of M-1. Semisynthetic derivative M-2 exhibited a similar 1H NMR spectrum to that of M-1 except for resonance differences attributed to the oxobutyl moiety. The chemical shift of H-2‴ (δH 2.97) in M-1 was shifted upfield to δH 2.74 in M-2 and two methylene protons (δH 3.94, d, J = 17.5 Hz; δH 4.02, d, J = 17.5 Hz) were observed. This indicated that a methylene group was inserted between C-8 and the ketone carbonyl carbon in the structure of M-2. The structure of M-3 was deduced to be the 5,7-dimethoxy-substituted derivative of 1 because no H-bonded hydroxy proton was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum and H-1′ (δH 5.19) was shifted downfield relative to that observed in M-1 (δH 4.72). Similarly, M-4 was deduced to be the C-8/C-1‴-carbon-inserted derivative of M-3 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Structures of semisynthetic derivatives of 1 and selected Δδ values [Δδ (in ppm) = δS−δR] for (S)- and (R)-MTPA esters of M-3.

The absolute configuration of C-1′ in 1 was determined by use of the modified Mosher’s method on its M-3 di-O-methylated derivative.13 Use of this semisynthetic product ensured the protection of the two phenolic hydroxy groups. Samples of M-3 (Figure 2) were treated with (S)- and (R)-MTPA chloride, respectively. The proton resonances of the (R)- and (S)-MTPA esters of M-3 were assigned based on observation of the 1H-1H correlations, and the change in the proton chemical shifts of these MTPA ester derivatives (Δδ = δS−δR) indicated that 1 possesses a C-1′ S-configuration.13 The absolute configuration of the stereogenic carbon in the 2-methyl-oxobutyl substituents in the previously reported mammea-type coumarins have been inferred to be of an S-configuration by synthesis of natural (−)-mammea B/BB (10).14 All previously identified 2-methyl-oxobutyl-substituted Mammea coumarins [mammea C/AB (4), mammea C/BB (6), mammea B/AB (8), mammea B/BB (10), mammea A/AB (12), and mammea A/BB (14)] isolated from M. americana that contain this single stereogenic carbon, display negative specific rotations. Therefore, 1 was deduced to be similarly derived biogenetically with an S-configuration at C-2‴. Using the established mammea-letter designation system designation that defines the branching pattern with letter designations,6 1 was assigned the trivial name mammea F/BB. Because 1 contains an unprecedented R1-substituent, the new letter ‘F’ is used to define this new coumarin mammea class.

Compound 2 was obtained as a pale brown oil with the same molecular formula as 1 (C24H32O6), as determined by HRESIMS. The UV, IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 2 were similar to those of 1, indicating that the two analogues possess a similar structural architecture. Discrepancies were observed in the 1H and 13C NMR resonances observed for the oxobutyl moiety. Further, 1H-1H COSY correlations between two methyl resonances [(δH 0.96, d, CH3-4‴) and (δH 0.98, d, CH3-5‴)] and a methine resonance (δH 2.16, m, H-3‴), and between H-3‴ and two methylene protons (δH 2.97, dd, H-2‴a; δH 2.80, dd, H-2‴b) were indicative of a 3-methyl-oxobutyl moiety (Figure 1). This partial structure was further supported by observation of 1H-13C HMBC correlations from H-3‴ (δH 2.16) and 2H-2‴ (δH 2.97/2.80) to the C-1‴ (δC 205.1) carbonyl carbon, indicating that the 3-methyl-oxobutyl moiety is attached to C-8 (Figure 1). As for 1, compound 2 was assigned a C-1′S-configuration based on observation of its similar negative specific rotation ([α]24D −14.7). Thus, 2 was deduced to be 5,7-dihydroxy-4-(1S-hydroxypentyl)-6-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)-8-(3-methylbutanoyl)-2H-chrom en-2-one. The trivial name mammea F/BB is proposed for 2.

Compound 3 was isolated as pale brown oil and deduced to have the molecular formula C24H32O5 by HRESIMS (m/z 423.2149 [M+Na]+). Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 3 with those of 2 indicated that both compounds possess the identical 5,7-dihydroxycoumarin nucleus substituted with the same 3-methyl-oxobutyl and prenyl moieties. However, these two side-chain substituents were deduced to have a reversed substitution pattern in 3, relative to the structure of 2, based on HMBC correlations observed from 2H-1‴ (δH 3.55) to C-7 (δC 160.1), C-8 (δC 105.1), and C-8a (δC 157.5) (Figure 1). In contrast to the 10 ppm difference in carbon chemical shift observed in 1 and 2, C-6 (δC 107.2) was observed to be shifted only 2.1 ppm downfield from the resonance observed for C-8.7–9 Further, analysis of the 1H-1H COSY spectrum of 3 indicated the presence of a C-4 n-pentyl substituent. The substitution pattern was further supported by observation of HMBC correlations from the 2H-1′ (δH 2.95) protons to the C-3 (δC 110.0) and C-4a (δC 103.6) carbon resonances. Thus, the structure of 3 (simply referred to as mammea C/AA) was deduced to be 5,7-dihydroxy-8-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)-6-(3-methylbutanoyl)-4-pentyl-2H-chromen-2-one.

Based on their C-4 substitution patterns, the fifteen natural mammea coumarins were classified into four groups: a) 4-(2-hydroxypentyl derivatives) (1 and 2); b) 4-pentyl derivatives (3 – 6); c) 4-propyl derivatives (7 – 10); and d) 4-phenyl derivatives (11 – 14). Mammea E/BB (15) is considered as an acetylated class I coumarin. Concentration-response studies were performed to determine the effects of mammea coumarins and their derivatives on HIF-1 activation in a cell-based reporter assay. In human breast tumor T47D cells, the natural mammea coumarins inhibited both hypoxia- and iron chelator-induced HIF-1 activation with comparably low micromolar IC50 values (Table 2). A similar activity profile was obtained from a concentration-response study performed in a human prostate tumor PC-3 cell-based reporter assay (Supporting Information, Table S1). In both cell lines, the class II compounds (3 – 6) exhibited higher potencies than the corresponding class III analogues (7 – 10) that bear the same C-6 and C-8 substituent patterns. These observations suggested that the length of the alkyl side chain on C-4 significantly affects the HIF-1 inhibitory activity of the mammea-type coumarins. Furthermore, hydroxylation of the 4-pentyl side chain in the class I compounds (1 and 2) slightly enhanced their overall potency. It is noteworthy that four of the coumarins that bear the same 6-prenyl-8-(3-methyl-oxobutyl)-substituent pattern (2, 5, 9, and 13), were the most potent inhibitors in each group, indicating that the 6-prenyl-8-(3-methyl-oxobutyl)-substituent pattern is associated with enhanced HIF-1 inhibitory effects. To exclude the possibility that the general suppression of luciferase expression or enzymatic activity contributed to the HIF-1 inhibitory activities, the effects of 1 – 15 on luciferase expression from a control construct (pGL3-Control, Promega) were examined in T47D cells. At the highest concentration tested (20 μM), luciferase expression from pGL3-Control (33 – 54% inhibition, data not shown). Since 10 out of 15 compounds inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation with IC50 values below 5 μM (Table 2), it is clear that the HIF inhibitory effects exhibited by these compounds are relatively selective.

Table 2.

IC50 Values of 1 – 14, M-1 – M-4, and A-1 – A-3 suppressing HIF-1 Activation in a T47D Cell-based Reporter Assay.

| compound | 1% O2, 16 h | 10 μM 1,10-phen, 16 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 μM | (95% CI) μM | IC50 μM | (95% CI) μM | |

| 1 | 2.23 | (1.94 – 2.56) | 2.30 | (2.02 – 2.62) |

| 2 | 1.72 | (1.52 – 1.93) | 1.81 | (1.46 – 2.24) |

| 3 | 4.19 | (3.83 – 4.57) | 4.12 | (3.46 – 4.90) |

| 4 | 5.70 | (5.23 – 6.20) | 5.31 | (4.68 – 6.03) |

| 5 | 2.76 | (2.53 – 3.00) | 2.71 | (2.42 – 3.04) |

| 6 | 3.73 | (3.45 – 4.03) | 3.40 | (2.97 – 3.90) |

| 7 | 9.40 | (8.50 – 10.4) | 9.56 | (8.54 – 10.71) |

| 8 | 9.96 | (8.75 – 11.3) | 8.21 | (7.29 – 9.26) |

| 9 | 2.20 | (1.79 – 2.71) | 1.28 | (0.96 – 1.70) |

| 10 | 5.04 | (4.16 – 6.11) | 3.25 | (2.80 – 3.77) |

| 11 | 4.44 | (3.82 – 5.16) | 3.71 | (2.99 – 4.60) |

| 12 | 4.63 | (3.92 – 5.46) | 4.82 | (4.20 – 5.54) |

| 13 | 3.23 | (2.95 – 3.54) | 3.73 | (3.03 – 4.59) |

| 14 | 6.76 | (6.31 – 7.25) | 5.96 | (5.30 – 6.71) |

| M-1 | 13.2 | (11.9 – 14.7) | 18.4 | (14.6 – 23.2) |

| M-2 | 5.91 | (5.26 – 6.65) | 15.7 | (13.4 – 18.4) |

| M-3 | 6.31 | (5.57 – 7.14) | 6.50 | (6.03 – 7.01) |

| M-4 | 7.42 | (6.04 – 9.11) | 11.3 | (10.2 – 12.6) |

| A-1 | 5.11 | (4.24 – 6.16) | 5.47 | (4.91 – 6.10) |

| A-2 | 0.83 | (0.80 – 0.86) | 1.06 | (0.98 – 1.15) |

| A-3 | 2.06 | (1.76 – 2.42) | 1.68 | (1.41 – 2.00) |

| 15 | 0.96 | (0.91 – 1.01) | 0.90 | (0.77 – 1.06) |

The IC50 and 95% CI values were determined from one representative of two independent experiments each performed in triplicate. The data on mammea E/BB (15) were from an earlier publication.10

To further examine the structure-activity relationships of mammea-type coumarins, compound 1 was selected as a prototypical representative to prepare derivatives for SAR studies due to its greater yield and availability. In addition to the four O-methoxylated derivatives M-1 – M-4 (Figure 2), compound 1 was also acetylated (Ac2O/pyridine) to yield three O-acetoxylated derivatives A-1, A-2, and A-3. The acetylated semisynthetic derivative A-1 was found to have a molecular formula C28H36O8 by HRESIMS, indicative of a di-O-acetylated product of 1. In the 1H NMR spectrum, two new singlet methyl resonances were observed (δH 2.17 and 2.26), while the H-bonded hydroxy OH-7 (δH 14.20) resonance that was originally seen in 1 was not observed in A-1 and the H-1′ (δH 6.52) resonance was shifted dramatically downfield in this acetylated derivative. Therefore, the structure of A-1 was deduced to be acetylated at C-7 and C-1′. The 1H NMR spectrum of A-2 exhibited three new singlet methyl resonances that were observed at δH 2.18, 2.22, and 2.41, respectively. Based on the molecular formula, C30H38O9, the structure of A-2 was deduced to be the tri-O-acetylated product of 1. Semisynthetic derivative A-3 possessed the same molecular formula as A-1 and was deduced to be a second di-O-acetylated product of 1. A H-bonded hydroxy resonance at δH 14.25 (OH-7) was observed, indicating that A-3 is acetylated at C-5 and C-1′.

The effects of four O-methylated and three O-acetylated derivatives of 1 on HIF-1 activation were evaluated in a T47D cell-based reporter assay, alongside the fifteen natural products (Table 2). All three acetylated products A-1, A-2, and A-3, inhibited both hypoxia- and iron chelator-induced HIF-1 activation with comparable low micromolar IC50 values. The tri-O-acetylated derivative A-2 was more potent than the natural product 1, exhibiting high nanomolar IC50 values. However, the four O-methylated products M-1, M-2, M-3, and M-4, all displayed reduced potency at suppressing HIF-1 activation, when compared to the natural product 1. A similar HIF-1 inhibitory profile was observed in a parallel PC-3 cell-based reporter assay (Supporting Information, Table S1).

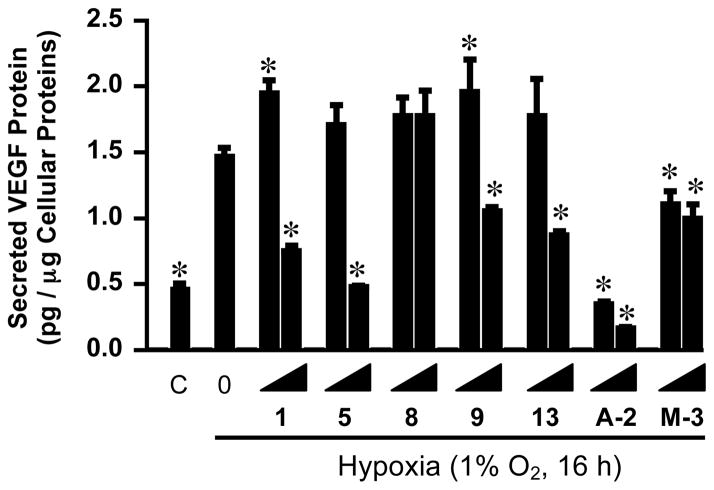

Since HIF-1 primarily functions as a transcription factor, the expression of HIF-1 target gene vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was examined to determine if these mammea-type coumarins also regulate target genes downstream of HIF-1. The protein VEGF is an important angiogenic factor and agents that inhibit VEGF are in clinical use for cancer and other diseases affected by angiogenesis.15 The T47D cells were exposed to hypoxic conditions in the presence (or absence) of five representative mammea-type natural coumarins (1, 5, 8, 9, and 13) and two derivatives of 1 (M-3 and A-2). The levels of secreted VEGF protein were measured by ELISA and normalized to the amount of cellular proteins. Hypoxic exposure increased the level of secreted VEGF protein to approximately three times that of the normoxic control (Figure 3). The most potent HIF-1 inhibitor A-2 blocked the induction of secreted VEGF protein at concentrations as low as 3 μM (Figure 3). The less potent coumarins 1, 5, 9, 13, and M-3 exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition on the hypoxic induction of secreted VEGF protein with reduced potency, relative to A-2 (Figure 3). In contrast, the relatively weak compound 8 did not inhibit the hypoxic induction of secreted VEGF protein at concentrations up to 10 μM (Figure 3). These results mirror those observed in the T47D cell-based reporter assay for HIF-1 activity (Table 2). However, compounds 1 and 9 increased secreted VEGF protein levels by ~20% at 3 μM. Compound M-3 also inhibited the induction of secreted VEGF protein at concentrations as low as 3 μM (Figure 3), below the IC50 value observed in the reporter assay (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent effects of compounds 1, 5, 8, 9, 13, A-2, and M-3 on the hypoxic induction of secreted VEGF protein. T47D cells were exposed to hypoxic conditions (1% O2, 16 h) in the presence of compounds at the incrementing concentrations of 3 and 10 μM, respectively. Levels of VEGF in the conditioned medium samples were determined by ELISA and normalized to the amount of cellular proteins. The sample “C” represents normoxic control, while “0 under Hypoxia” stands for the medium control under hypoxic conditions. Data shown are average + standard deviation from one experiment performed in triplicate. The asterisk “*” indicates that the difference between the specified sample and the hypoxic media control is statistically significant (p < 0.05).

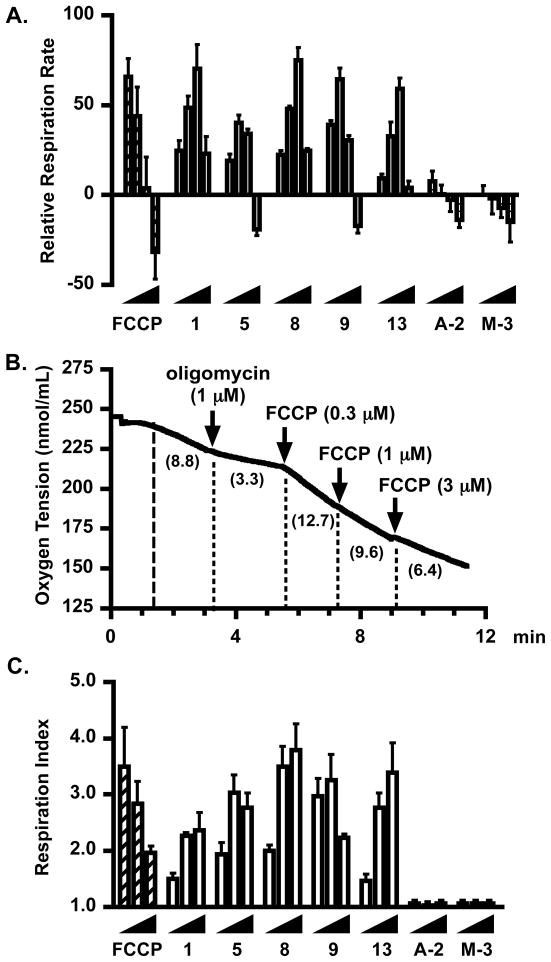

Coumarins have been shown to dysregulate mitochondrial respiration by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation and inhibiting succinate oxidase.16–18 Our recent studies have established that mammea E/BB (15) can function as an anionic proton translocator mitochondrial uncoupler (protonophore) that dissipates the mitochondrial proton gradient, thereby initiating an increase in respiration rate.10 If the uncoupling is sufficiently strong, the loss of mitochondrial ATP synthesis along with the reversal of ATP synthase can result in the depletion of cellular ATP, causing glycolytic failure and hence an eventual reduction in respiratory chain activity. In order to determine if the HIF-1 inhibitory activity correlates with the effect on mitochondrial respiration, a concentration-response study was performed in a T47D cell-based respiration assay19 with natural coumarins representative of each group and two derivatives of 1. The commonly used mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP (carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) was used a positive control for uncouplers that inhibit HIF-1 activation in T47D cells.10 At the range of concentrations tested (0.3 – 10 μM in half-log increments), compounds 1, 5, 8, 9, and 13 stimulated oxygen consumption at lower concentrations, while their effects were diminished or they actually inhibited at higher concentrations (Figure 4A). This biphasic pattern of activities mirrors that observed with FCCP (Figure 4A). Although 8 was one of the less potent HIF-1 inhibitors in the T47D cell-based reporter assay (Table 2), its effect on oxygen consumption in T47D cells parallels that observed in the presence of 1, one of the more potent HIF-1 inhibitors. The two coumarin derivatives A-2 and M-3 did not significantly effect T47D cell respiration (Figure 4A). An earlier study demonstrated that mammea E/BB (15) stimulates T47D cell respiration by uncoupling the mitochondrial proton gradient.10 To determine if these related compounds stimulate respiration by acting as mammea E/BB (15)-like protonophores, the effects of 1, 5, 8, 9, 13, A-2, and M-3 on T47D cell respiration were examined in the presence of oligomycin. Acting as an inhibitor of F0F1ATPase, oligomycin increases the mitochondrial proton gradient, slows mitochondrial electron transport, and initiates state 4 respiration as reflected by a decrease in the rate of oxygen consumption (Figure 4B). Uncouplers such as FCCP are known to stimulate state 4 respiration (Figure 4B). Compounds 1, 5, 8, 9, and 13 all stimulated state 4 respiration (Figure 4C). The decrease in the extent of stimulation at higher concentrations is most likely caused by a reduced rate in mitochondrial electron transport following excessive uncoupling. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that mammea coumarins dysregulate mitochondria respiration by functioning as protonophores that uncouple the electron transport chain. As shown earlier (Figure 4A), M-3 and A-2, which lack free phenolic groups, did not stimulate state 4 respiration (Figure 4C). Since A-2 potently inhibited HIF-1 activation in the cell-based reporter assay (IC50 0.83 μM for hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation, Table 2), one possible explanation is that the lipophilic nature of this peracetylated derivative enhances its cellular penetration, and the extended 16 h incubation time during the reporter assay allows this compound to be gradually hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases that free the acidic phenolic hydroxy moieties, thus generating the resulting metabolite that uncouples mitochondrial respiration and interferes with mitochondrial-mediated HIF-1 signaling.

Figure 4.

Effects of compounds 1, 5, 8, 9, 13, A-2, and M-3 on cellular respiration. (A) Concentration–response results of 1, 5, 8, 9, 13, A-2, M-3, and the uncoupler standard FCCP on oxygen consumption in T47D cells. All compounds were tested at the incrementing concentrations of 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 μM. Oxygen consumption rates were determined and presented as Relative Respiration Rate, in comparison to the untreated control. Data show are average + standard deviation from three independent experiments. (B) Oxygen concentrations in the presence of respiring T47D cells, oligomycin (1 μM), and the uncoupler FCCP at the specified concentrations. (C) Concentration–response results of 1, 5, 8, 9, 13, A-2, M-3, and FCCP on state 4 respiration initiated by the addition of oligomycin. Test compounds were added at the incrementing concentrations of 0.3, 1, and 3 μM. Oxygen consumption rate data were presented as Respiration Index to compare the effects of compounds at stimulating state 4 respiration in T47D cells. Data show are average + standard deviation from three independent experiments.

The effects of the natural and semisynthetic coumarins on cell proliferation/viability were examined in human tumor cell line-based models. The compounds were tested at the same range of concentrations (0.31 to 20 μM) used in the HIF-1 reporter assays. In human breast tumor T47D cells, M-3 and A-2 exhibited the most pronounced cytostatic/cytotoxic effects (48 h exposure) at the highest concentration tested (20 μM, 91 ± 1% and 82 ± 1% inhibition, respectively, n = 3). The other compounds yielded a concentration-response curve(s) that plateaued around 50% inhibition, similar to that previously reported for mammea E/BB.10 To compare the activities between these structurally related compounds, EC50 values were determined (Table 3). In general, the less active HIF-1 inhibitors 3, 4, 7, 8, 10–12, 14, M-1–M-4, and A-1 displayed higher EC50 values (> 2.5 μM), while the more active HIF-1 inhibitors exhibited lower EC50 values (< 2.5 μM). A similar activity profile was observed for human prostate tumor PC-3 cells (Table 3). At 20 μM, M-3 and A-2 inhibited the proliferation/viability of PC-3 cells by 93 ± 1% and 65 ± 0%, respectively, n = 3. Although the more potent HIF-1 inhibitors suppressed cell proliferation/viability, there is a window (2 to > 20-fold difference in IC50 values) between the HIF-1 inhibitory activities and the observed cytotoxicity of these compounds.

Table 3.

EC50 Values of 1 – 14, M-1 – M-4, and A-1 – A-3 on the Proliferation/Viability of Human Breast Tumor T47D and Prostate Tumor PC-3 Cells in a 48 h Exposure Concentration-Response Study.

| compound | T47D | PC-3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 μM | (95% CI) μM | EC50 μM | (95% CI) μM | |

| 1 | 1.36 | (1.19 – 1.54) | 2.09 | (1.91 – 2.28) |

| 2 | 0.91 | (0.79 – 1.06) | 1.14 | (1.01 – 1.29) |

| 3 | 3.13 | (2.81 – 3.49) | 3.36 | (3.06 – 3.68) |

| 4 | 3.57 | (3.14 – 4.07) | 4.18 | (3.52 – 4.96) |

| 5 | 1.36 | (1.18 – 1.57) | 1.88 | (1.66 – 2.13) |

| 6 | 1.56 | (1.31 – 1.85) | 2.19 | (1.44 – 3.33) |

| 7 | 3.62 | (3.11 – 4.23) | 7.03 | (5.91 – 8.37) |

| 8 | 5.52 | (5.20 – 5.85) | 10.5 | (8.92 – 12.5) |

| 9 | 1.32 | (1.19 – 1.46) | 2.27 | (1.89 – 2.71) |

| 10 | 3.22 | (2.85 – 3.63) | 6.05 | (5.10 – 7.18) |

| 11 | 4.28 | (3.95 – 4.62) | 5.31 | (4.94 – 5.71) |

| 12 | 2.88 | (2.61 – 3.19) | 3.82 | (3.50 – 4.16) |

| 13 | 1.57 | (1.40 – 1.76) | 2.18 | (2.04 – 2.33) |

| 14 | 4.01 | (3.73 – 4.31) | 5.26 | (4.91 – 5.65) |

| M-1 | 6.95 | (6.28 – 7.68) | > 20 | N/A |

| M-2 | 4.67 | (4.31 – 5.06) | > 20 | N/A |

| M-3 | 4.54 | (4.08 – 5.05) | 6.41 | (5.39 – 7.62) |

| M-4 | 6.18 | (5.84 – 6.54) | 10.6 | (9.37 – 11.9) |

| A-1 | 4.72 | (4.17 – 5.35) | 6.41 | (5.02 – 8.17) |

| A-2 | 0.73 | (0.62 – 0.85) | 1.17 | (1.03 – 1.32) |

| A-3 | 0.97 | (0.85 – 1.11) | 1.16 | (0.98 – 1.37) |

| 15 | 0.28 | (0.23 – 0.34) | 0.98 | (0.93 – 1.04) |

The EC50 and 95% CI values were determined from one experiment performed in triplicate. For comparison purpose, the maximum inhibition was set at 50% for T47D and 40% for PC-3 cells.

Over 1300 members of the coumarin family have been identified.20 Many coumarin derivatives such as 4-hydroxycoumarin (4-HC), 7-hydroxycoumarin (7-HC), and auraptene (7-geranyloxycoumarin; aurapten) have shown significant antitumor activities.21 A wide spectrum of mechanisms has been proposed for their antitumor activities, ranging from the inhibition of protein kinases and matrix metalloproteinsae (MMP), to interference with mitotic spindle formation.21 We recently reported that the mammea-type coumarin mammea E/BB (15), the most potent HIF-1 inhibitor isolated from Mammea americana, inhibited HIF-1 activation, uncoupled mitochondrial respiration, and suppressed cell proliferation/viability within the same range of concentrations.10 This current preliminary SAR study demonstrates that the 6-prenyl-8-(3-methyl-oxobutyl)-substituent pattern increased the HIF-1 inhibitory potency relative to those coumarins similarly substituted at C-8. The tri-O-acetoxylated derivative (A-2) is envisioned to potentially function as a “prodrug” that is gradually released by intracellular esterases to yield the phenolic metabolite that uncouples respiration following extended cell incubation. Although many cellular targets have been suggested, few plausible mechanisms of action may better explain the wide variety of biological activities attributed to these metabolites than their ability to uncouple mitochondrial electron transport and disrupt mitochondrial-mediated cellular signaling.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

A Bruker Tensor 27 Genesis Series FTIR was used to obtain the IR spectra, and a Varian 50 Bio spectrophotometer was used to record the UV spectra. The NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 on AMX-NMR spectrometers (Bruker) operating at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C, respectively. Residual solvent resonances (7.26 for 1H and 77.16 for 13C) were used as internal references for the NMR spectra recorded running gradients. The HRESIMS were determined on a Bruker Daltonic micro TOF fitted with an Agilent 1100 series HPLC and an electrospray ionization source. The TLCs were performed using Merck Si60F254 or Si60RP18F254 plates, sprayed with a 10% H2SO4 solution in EtOH, heated, and visualized under UV at 254 nm. HPLC was performed on a Waters system, equipped with a 600 controller and a 996 photodiode array detector. Two semipreparative HPLC columns [(1) Phenomenex Luna RP-18, 5 μm, 250 × 10.00 mm and (2) Phenomenex Luna Phenyl-Hexyl, 5 μm, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm] were employed for isolation. Various isocratic and gradient solvent systems comprised of MeOH/H2O or MeCN/H2O were used to generate the best resolution of each compound. The purity of all compounds was judged on the percentage of the integrated signal at UV 220 nm. All final compounds submitted for bioassay were at least 95% pure as judged by this method (Supporting Information).

Plant Material

Mammea americana stem bark was collected in Dominica (August 1992). The plant material was identified by Dr. Kendall Lee (New York Botanical Gardens, Bronx, NY). The NCI Open Repository Sample number N071413 was assigned to the sample. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC.

Extraction and Isolation

Dried plant material was extracted with CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1), residual solvents were removed under vacuum, and the extract (N071413) stored at −20 °C in the NCI repository at the Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, Maryland). The crude extract (4.10 g sample from an NCI stock supply) inhibited hypoxia (1% O2)-induced HIF-1 activation by 89% at 5 μg/mL in a PC3 cell-based reporter assay and was separated into nine fractions by Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography [CHCl3 in MeOH (1:1)]. The active fraction Fr. 3 (1.60 g) inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation by 94% at 5 μg/mL and was further separated into six subfractions by C18 VLC column chromatography (eluted with step gradients of 10% to 100% MeOH in H2O). The active subfraction Fr. 3–4 (1.08 g, eluted with 80% MeOH in H2O) inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation by 93% at 5 μg/mL and was subjected to passage over a Sephadex LH-20 column eluted with hexanes-CH2Cl2-MeOH (2:1:1). The active subfraction Fr. 3-4-3 (207 mg) inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation by 89% at 5 μg mL−1 and was separated by reversed-phase HPLC (Luna 5 μm, ODS-3, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm, isocratic 85% CH3OH in 0.1% TFA, 4.0 mL min−1) to produce 3 (21.1 mg, 0.51% yield), 4 (25.4 mg, 0.62% yield), and 6 (22.1 mg, 0.54% yield). The active subfraction Fr. 3-4-4 (233 mg) inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation by 93% at 5 μg mL−1 and was subjected to reversed-phase HPLC (Luna 5 μm, ODS-3, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm, isocratic 85% CH3OH in 0.1% TFA, 4.0 mL/min) to produce 5 (13.6 mg, 0.33% yield) and an active subfraction, Fr. 3-4-4-2 (72.6 mg). This was separated further by reversed-phase HPLC (Luna 5 μm, Phenyl-Hexyl, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm, isocratic 90% CH3OH in 0.1% TFA, 4.0 mL/min) to give 9 (24.1mg, 0.59% yield), 10 (10.4 mg, 0.25% yield), 13 (4.9 mg, 0.12% yield), and 14 (2.1 mg, 0.05% yield). The active subfraction Fr. 3-4-5 (462 mg) inhibited hypoxia-induced HIF-1 activation by 93% at 5 μg mL−1 and was further separated by reversed-phase HPLC (Luna 5 μm, ODS-3, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm, isocratic 85% CH3OH in 0.1% TFA, 4.0 mL/min) to produce 1 (56.6 mg, 1.38% yield), 2 (7.8 mg, 0.19% yield), 7 (18.9 mg, 0.46% yield), 8 (16.0 mg, 0.39% yield), 11 (61.2 mg, 1.49% yield), and 12 (64.4 mg, 1.57% yield).

Mammea F/BB (1)

Pale brown oil; [α]24D −19.5 (c 0.40, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 224 (4.26), 254 (3.84), 328 (4.34) nm; IR (film) νmax 3306, 2961, 2930, 2873, 2676, 1709, 1607, 1560, 1423, 1377, 1340, 1264, 1236, 1201, 1139, 1125, 1095, 1050, 1013 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 439.2104 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C24H32O6Na, 439.2097).

Mammea F/BA (2)

Pale brown oil; [α]24D −14.7 (c 0.40, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 202 (4.26), 222 (4.24), 254 (3.85), 328 (4.31) nm; IR (film) νmax 3306, 2968, 2928, 2871, 2672, 1711, 1605, 1463, 1423, 1376, 1294, 1235, 1201, 1150, 1126, 1092, 1052, 849 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 439.2135 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C24H32O6Na, 439.2097).

Mammea C/AA (3)

Pale brown oil; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 202 (4.43), 234 (4.12), 288 (4.24), 372 (3.82), 406 (3.84) nm; IR (film) νmax 3306, 2957, 2930, 2870, 1709, 1613, 1581, 1536, 1501, 1462, 1428, 1378, 1299, 1181, 1145, 1112, 1082, 926, 842, 714 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 423.2149 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C24H32O5Na, 423.2147).

Methylation of 1

To a suspension of 1 (6 mg) in 1.5 mL MeOH was added 2.0 mL diazomethane in Et2O. The mixture was kept at −20 °C for 48 h and then the reaction was quenched by air drying. The residue was subjected to reversed-phase HPLC (Luna 5 μm, ODS-3, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm, isocratic 90% CH3CN in H2O, 4.0 mL/min) to produce M-1 (1.5 mg, 25.0% yield), M-2 (0.2 mg, 3.3% yield), M-3 (0.5 mg, 8.3% yield), and M-4 (0.1 mg, 1.7% yield).

5-O-,7-O-,1′-O-Trimethoxymammea F/BB (M-1)

Pale brown oil; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.33), 295 (3.93) nm; 1 H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.59 (1H, d, J = 0.8 Hz, H-3), 3.77 (6H, s, OCH3-5, OCH3-7), 4.72 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H-1′), 3.39 (3H, s, OCH3-1′), 1.72 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.35 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.42 (2H, m, H-3′), 1.33 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.90 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, H-5′), 3.46 (1H, dd, J = 7.2, 15.2 Hz, H-1″a), 3.30 (1H, dd, J = 5.6, 15.2 Hz, H-1″b), 5.16 (1H, dd, J = 5.6, 7.2 Hz, H-2″), 1.76 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.70 (3H, s, H-5″), 2.97 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.20 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-3‴), 1.85 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.45 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 0.99 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴); HRESIMS m/z 481.2567 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C27H38O6Na, 481.2566).

5-O-,7-O-,1′-O-Trimethoxy-8(1‴)a-homomammea F/BB (M-2)

Pale brown oil; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.34), 300 (3.81) nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ6.56 (1H, s, H-3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3-5), 3.72 (3H, s, OCH3-7), 4.74 (1H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H-1′), 3.38 (3H, s, OCH3-1′), 1.74 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.35 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.41 (2H, m, H-3′), 1.31 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.90 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, H-5′), 3.46 (1H, dd, J = 7.1, 15.4 Hz, H-1″a), 3.32 (1H, dd, J = 5.8, 15.4 Hz, H-1″b), 5.19 (1H, br t, J = 6.0 Hz, H-2″), 1.76 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.69 (3H, s, H-5″), 3.94 (1H, d, J = 17.5 Hz, H-1‴a), 4.02 (1H, d, J = 17.5 Hz, H-1‴b), 2.74 (1H, m, H-3‴), 1.23 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-4‴), 1.85 (1H, m, H-5‴a), 1.50 (1H, m, H-5‴b), 0.98 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-6‴); HRESIMS m/z 495.2736 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H40O6Na, 495.2723).

5-O-,7-O-Dimethoxymammea F/BB (M-3)

Pale brown oil; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 205 (4.26), 295 (3.84) nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ6.70 (1H, s, H-3), 3.77 (6H, s, OCH3-5, OCH3-7), 5.19 (1H, m, H-1′), 1.86 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.59 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.45 (2H, m, H-3′), 1.36 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.94 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-5′), 3.46 (1H, dd, J = 7.1, 15.4 Hz, H-1″a), 3.32 (1H, dd, J = 5.4, 15.4 Hz, H-1″b), 5.19 (1H, m, H-2″), 1.77 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.71 (3H, s, H-5″), 2.97 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.21 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-3‴), 1.85 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.45 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 1.00 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴); HRESIMS m/z 467.2392 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C26H36O6Na, 467.2410).

5-O-,7-O-Dimethoxy-8(1‴)a-homomammea F/BB (M-4)

Pale brown oil; UV (MeOH) λ max (log ε) 205 (4.27), 295 (3.72) nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.66 (1H, s, H-3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3-5), 3.72 (3H, s, OCH3-7), 5.20 (1H, m, H-1′), 1.88 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.56 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.45 (2H, m, H-3′), 1.38 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.94 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, H-5′), 3.46 (1H, dd, J = 7.1, 15.4 Hz, H-1″a), 3.34 (1H, dd, J = 5.4, 15.4 Hz, H-1″b), 5.19 (1H, m, H-2″), 1.77 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.70 (3H, s, H-5″), 3.95 (1H, d, J = 17.5 Hz, H-1‴a), 4.02 (1H, d, J = 17.5 Hz, H-1‴b), 2.74 (1H, m, H-3‴), 1.24 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-4‴), 1.85 (1H, m, H-5‴a), 1.50 (1H, m, H-5‴b), 0.99 (3H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, H-6‴); HRESIMS m/z 481.2569 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C27H38O6Na, 481.2566).

Preparation of (S)-MTPA Ester (M-3a) of M-3

To a solution of M-3 (0.25 mg) in pyridine-d5 (0.17 mL) in an NMR tube was added (R)-(−)-MTPACl (1 μL). The reaction was monitored by 1H NMR (400 MHz) spectroscopy and found to be complete after 4 h (25 °C).

(S)-MTPA M-3 ester (M-3a)

1H NMR (pyridine-d5, 400 MHz) δ 6.678 (1H, s, H-3), 4.029 (3H, s, OCH3-5), 3.900 (3H, s, OCH3-7), 6.939 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz, H-1′), 1.868 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.604 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.356 (2H, m, H-3′), 1.214 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.786 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, H-5′), 3.564 (1H, dd, J = 7.1, 15.3 Hz, H-1″a), 3.522 (1H, m, H-1″b), 5.398 (1H, t, J = 6.6 Hz H-2″), 1.772 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.692 (3H, s, H-5″), 3.070 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.254 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-3‴), 2.025 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.541 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 0.950 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴).

Preparation of (R)-MTPA Ester (M-3b) of M-3

Compound M-3 (0.25 mg) was treated with (S)-(+)-MTPACl (1 μL) by the same procedure described above and the reaction was complete after standing for 1 h at 25 °C.

(R)-MTPA M-3 ester (M-3b)

1H NMR (pyridine-d5, 400 MHz) δ 6.228 (1H, s, H-3), 4.022 (3H, s, OCH3-5), 3.892 (3H, s, OCH3-7), 6.859 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H-1′), 1.872 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.623 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.511 (2H, m, H-3′), 1.311 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.837 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5′), 3.562 (1H, dd, J = 6.2, 14.7 Hz, H-1″a), 3.520 (1H, m, H-1″b), 5.396 (1H, t, J = 6.3 Hz H-2″), 1.767 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.691 (3H, s, H-5″), 3.053 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.236 (3H, d, J = 6.9 Hz, H-3‴), 2.008 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.545 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 0.938 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴).

Acetylation of 1

Compound 1 (10 mg) was dissolved in pyridine (1.0 mL) and treated with 2 mL Ac2O at room temperature for 4 h. EtOH (2 mL) was added to quench the reaction and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Luna 5 μm, ODS-3, 100 Å, 250 × 10.00 mm, isocratic 85% CH3CN in H2O, 4.0 mL/min) to produce A-1 (1.3 mg, 11.9% yield), A-2 (2.3 mg, 19.6% yield), and A-3 (1.1 mg, 10.1% yield).

7-O-,1′-O-Diacetylmammea F/BB (A-1)

Pale brown oil; [α]24D −11.4 (c 0.04, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (log ε) 205 (4.35), 260 (4.03), 291 (3.98, sh) nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.37 (1H, d, J = 0.9 Hz, H-3), 2.26 (3H, s, OAc-7), 6.52 (1H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, H-1′), 2.17 (3H, s, OAc-1′), 1.91 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.61 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.38 (1H, m, H-3′a), 1.34 (1H, m, H-3′b), 1.33 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.89 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-5′), 3.26 (2H, d, J = 6.9 Hz, H-1″), 5.23 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-2″), 1.82 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.86 (3H, s, H-5″), 3.12 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.16 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-3‴), 1.85 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.44 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 0.98 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴); HRESIMS m/z 523.2303 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H36O8Na, 523.2308).

5-O-,7-O-,1′-O-Triacetylmammea F/BB (A-2)

Pale brown oil; [α]24D −7.3 (c 0.08, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (log ε) 205 (4.31), 285 (3.85), 320 (3.59, sh) nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.54 (1H, d, J = 0.7 Hz, H-3), 2.41 (3H, s, OAc-5), 2.22 (3H, s, OAc-7), 6.29 (1H, d, J = 6.3 Hz, H-1′), 2.18 (3H, s, OAc-1′), 1.86 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.58 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.41 (1H, m, H-3′a), 1.38 (1H, m, H-3′b), 1.33 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.90 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, H-5′), 3.17 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 13.7 Hz, H-1″a), 3.06 (1H, dd, J = 7.0, 13.3 Hz, H-1″b), 4.96 (1H, br t, J = 6.4 Hz, H-2″), 1.68 (6H, s, H-4″, H-5″), 3.05 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.18 (3H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, H-3‴), 1.90 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.49 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 1.01 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴); HRESIMS m/z 565.2426 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C30H38O9Na, 565.2414).

5-O-,1′-O-Diacetylmammea F/BB (A-3)

Pale brown oil; [α]24D −10.9 (c 0.03, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ max (log ε) 215 (4.30), 280 (3.90), 340 (3.89) nm; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 6.43 (1H, s, H-3), 2.45 (3H, s, OAc-5), 14.25 (1H, s, OH-7), 6.34 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-1′), 2.18 (3H, s, OAc-1′), 1.81 (1H, m, H-2′a), 1.56 (1H, m, H-2′b), 1.41 (1H, m, H-3′a), 1.37 (1H, m, H-3′b), 1.34 (2H, m, H-4′), 0.91 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, H-5′), 3.31 (1H, m, H-1″ a), 3.18 (1H, m, H-1″b), 5.08 (1H, br t, J = 6.8 Hz, H-2″), 1.74 (3H, s, H-4″), 1.68 (3H, s, H-5″), 2.88 (1H, m, H-2‴), 1.26 (3H, d, J = 6.7 Hz, H-3‴), 1.91 (1H, m, H-4‴a), 1.49 (1H, m, H-4‴b), 1.00 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-5‴); HRESIMS m/z 523.2309 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H36O8Na, 523.2308).

Cell-Based Reporter and Proliferation/Viability Assay

T47D and PC-3 cells were obtained from ATCC. Cell maintenance, experimental procedures, and data presentation for the cell-based reporter and proliferation/viability assays were the same as previously described.10 For the PC3 cell-based reporter assay, compound treatment started 4 h after the cells were plated. All extract, fraction, and compound samples were prepared as stock solutions in DMSO (final solvent concentration less than 0.5% in all assays).

ELISA Assay for Secreted VEGF Protein

Experimental procedures and data presentation were the same as previously described.22

Cellular Respiration Assay

A T47D cell-based respiration assay19 was used to determine the concentration-dependent effects of compounds on cellular respiration. Data were presented as “Relative Respiration Rate” calculated using the formula

For mechanistic studies, oligomycin (1 μM) was added to respiring T47D cells, followed by test compounds or the standard uncoupler FCCP at the specified concentrations. Data are presented as “Respiration Index” calculated as:

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analyses were applied to analyze data using GraphPad Prism 4. Differences between data sets were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D.J. Newman and E.C. Brown (Natural Products Branch Repository Program, NCI – Frederick) for providing terrestrial and marine extracts and collection information, and S.L. McKnight (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas) for the pHRE-TK-luc construct. This research was supported in part, by NIH grant CA98787 (D.G.N./Y.-D.Z.) and NOAA/NIUST grant NA16RU1496. The work at the University of Mississippi was conducted in a facility constructed with NIH Research Facilities Improvement Grant C06 RR-14503-01.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Spectroscopic data (1H and 13C NMR) for 1 – 3. 1H NMR spectra of M-1 – M-4, and A-1 – A-3. Purity data for compounds evaluated in bioassays. Results from evaluation of 1 – 14, M-1 – M-4, and A-1 – A-3 in PC3-based HIF-1 assay. The material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225–339. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenza GL. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–634. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. [accessed October 15, 2010];US NIH database. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/search.

- 4.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagle DG, Zhou YD. Phytochem Rev. 2009;8:415–429. doi: 10.1007/s11101-009-9120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crombie L, Jones RCF, Palmer CJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1987;1:317–331. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reyes-Chilpa R, Estrada-Muniz E, Ramirez Apan T, Amekraz B, Aumelas A, Jankowski CK, Vazquez-Torres M. Life Sci. 2004;75:1635–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Protiva P, Gil RR, Jiang B, Baggett S, Basile MJ, Reynertson KA, Weinstein IB, Kennelly EJ. Planta Med. 2005;71:852–860. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verotta L, Lovaglio E, Vidari G, Finzi PV, Neri MG, Raimondi A, Parapini S, Taramelli D, Riva A, Bombardelli E. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2867–2879. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du L, Mahdi F, Jekabsons MB, Nagle DG, Zhou YD. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:1868–1872. doi: 10.1021/np100501n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakraborty DP, Chakraborti SK. The Ultraviolet Absorption Spectra of Some Natural Coumarins. Transactions of the Bose Research Institute; Calcutta: 1961. pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KH, Chai HB, Tamez PA, Pezzuto JM, Cordell GA, Win KK, Tin-Wa M. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:535–541. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohtani I, Kusumi T, Kashman Y, Kakisawa H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4092–4096. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begley MJ, Crombie L, Jones RCF, Palmer CJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1987;1:353–357. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara N, Mass RD, Campa C, Kim R. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:491–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.061705.145635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai MR, Bai NJ, Venkitasubramanian TA, Murthy VV. Environ Physiol Biochem. 1975;5:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai MR, Bai NJ, Venkitasubramanian TA, Murthy VV. Toxicology. 1975;4:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(75)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papa S, Lofrumento NE, Paradies G, Quagliariello E. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;180:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(69)90191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Veena CK, Morgan JB, Mohammed KA, Jekabsons MB, Nagle DG, Zhou YD. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5859–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806744200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kostova I. Curr Med Chem. 2005;5:29–46. doi: 10.2174/1568011053352550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu L, Wang X, Xu W, Farzaneh F, Xu R. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:4236–4260. doi: 10.2174/092986709789578187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou YD, Kim YP, Mohammed KA, Jones DK, Muhammad I, Dunbar DC, Nagle DG. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:947–950. doi: 10.1021/np050029m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.