Abstract

Skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with elevated apoptosis while muscle differentiation results in apoptosis resistance, indicating that the role of apoptosis in skeletal muscle is multifaceted. The objective of this study was to investigate mechanisms underlying apoptosis susceptibility in proliferating myoblasts compared to differentiated myotubes and we hypothesized that cell death-resistance in differentiated myotubes is mediated by enhanced anti-apoptotic pathways. C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes were treated with H2O2 or staurosporine (Stsp) to induce cell death. H2O2 and Stsp induced DNA fragmentation in more than 50% of myoblasts, but in myotubes less than 10% of nuclei showed apoptotic changes. Mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation was detected with H2O2 and Stsp in myoblasts, while this response was greatly diminished in myotubes. Caspase-3 activity was 10-fold higher in myotubes compared to myoblasts, and Stsp caused a significant caspase-3 induction in both. However, exposure to H2O2 did not lead to caspase-3 activation in myoblasts, and only to a modest induction in myotubes. A similar response was observed for caspase-2, -8 and -9. Abundance of caspase-inhibitors (apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC), and heat shock protein (HSP) 70 and -25 was significantly higher in myotubes compared to myoblasts, and in addition ARC was suppressed in response to Stsp in myotubes. Moreover, increased expression of HSPs in myoblasts attenuated cell death in response to H2O2 and Stsp. Protein abundance of the pro-apoptotic protein endonuclease G (EndoG) and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) was higher in myotubes compared to myoblasts. These results show that resistance to apoptosis in myotubes is increased despite high levels of pro-apoptotic signaling mechanisms, and we suggest that this protective effect is mediated by enhanced anti-caspase mechanisms.

Keywords: Myoblast, Myotube, Differentiation, ARC, Caspase, HSP

Introduction

Apoptosis is a critical mechanism that allows multi-cellular organisms to maintain tissue integrity and function, and to eliminate damaged or superfluous cells. Dysregulation of apoptosis has been implicated in a number of diseases including cancer, which is often characterized by insufficient apoptosis [1, 2]. In contrast, other conditions, such as neurodegenerative (Parkinson and Alzheimer), and autoimmune diseases have been linked to excessive apoptosis [3, 4]. Apoptosis in skeletal muscle occurs under a number of different pathological and physiological circumstances, such as chronic heart failure [5], neuromuscular diseases [6–9], aging [10–12], and disuse-induced atrophy [13–17]. The specific role of apoptosis in skeletal muscle atrophy is currently unclear, but it is thought to contribute to the loss of nuclei in different models of muscle atrophy such as spinal cord injury [14], hind limb suspension [17, 18], immobilization [13], denervation [19], or chronic heart failure [5], although recently this role has been challenged [20]. Gaining insight into the relevance and underlying mechanisms in the control of apoptosis might aid in identifying more efficient treatments for the loss of muscle mass [21, 22].

With regard to apoptosis, skeletal muscle is a unique tissue because of the multinucleated nature of muscle cells (or myofibers) and the flexibility in myonuclear number with hypertrophy and atrophy [23]. In muscles undergoing atrophy induced by a variety of conditions, the individual myonuclei, instead of entire cells, may be eliminated by the process of ‘apoptotic nuclear death’ [21]. Skeletal muscle also possesses remarkable recovery or regenerative capacity, and satellite cells have been shown to play an important role in this process [24, 25]. Enhanced satellite cell apoptosis, however, is thought to be related to compromised recovery potential in aged animals [26, 27] and therefore it is important to investigate mechanisms for apoptosis in both proliferating myoblasts (satellite cells) and in differentiated myotubes (skeletal muscle cells). The process by which multi- and mononucleated cells undergo apoptosis is likely quite different and we have recently shown that adult differentiated muscle cells utilize a caspase-independent mechanism for nuclear apoptosis [28]. In addition, Siu et al. [29] recently showed that multinucleated myotubes exhibit both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways of apoptosis in response to oxidative stress.

In general, cell differentiation results in increased apoptosis resistance which is particularly true for cancer cells and is a major problem in cancer therapy [2, 30]. Indeed, in muscle, increased apoptosis-resistance has also been observed in differentiated myotubes compared to proliferating myoblasts [31–35]. Apoptosis and cellular differentiation are two biologically distinct processes that nonetheless share biochemical and morphological features that imply that they are closely related [36]. For example, as nuclear disruption is viewed as an irreversible step in the apoptotic process, terminal differentiation of many cell types including erythrocytes, keratinocytes, and lens fiber epithelial cells are characterized by complete removal of the nucleus [37]. Also, caspases have been extensively used as a surrogate to monitor apoptosis, because of their central role in this process, but caspases have also been found to play non-apoptotic roles in pathways such as the inflammatory response, immune cell proliferation, and differentiation [38, 39]. Importantly, prodifferentiation functions of caspase-3 have been implicated for osteoclasts [40], bone marrow stromal cells [41], neurons [42], neural and glial progenitor cells [43, 44], and muscle cells [45], and these observations have led to the proposition that cell differentiation may be a modified or curtailed form of cell death [36, 46]. Larsen et al. [47] recently showed that caspase-3 promotes cell differentiation in muscle cells through the induction of DNA strand breaks, but it remains unclear how muscle cells regulate caspase-mediated differentiation and cell death signaling simultaneously and restrict apoptosis while undergoing differentiation. Therefore, the goal of current study was to investigate underlying mechanisms of the altered apoptosis susceptibility in myogenic C2C12 cells in response to differentiation. It seems contradictive that caspase activation is elevated with both differentiation and apoptosis induction, but differentiated myotubes are more resistant to apoptosis. We suggest that pathways are in existence in differentiated myotubes that inhibit apoptosis even under conditions where apoptosis would be favorable, such as high caspase activities, to prevent the death of postmitotic muscle tissue. Therefore, we hypothesize that differentiated muscle cells (myotubes) are more resistant to apoptosis than undifferentiated cells (myoblasts), because of enhanced anti-apoptosis pathways.

Methods

Cell culture and differentiation

The C2C12 cell line was grown as described previously with a few revisions [48]. Briefly, C2C12 cells were maintained as myoblasts in subconfluent conditions in growth medium (GM: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) at 37°C in a humidified, 10% CO2 incubator. To induce differentiation from myoblasts to myotubes, cells at 95–100% confluency were switched to differentiation medium (DM: DMEM plus 2% horse serum) and maintained in DM for 3 days. Myogenin gene expression was used to show the highly differentiated cells after 3 days in DM.

Induction of apoptosis

Two apoptosis inducers, H2O2 and staurosporine (Stsp), were used to investigate the mechanisms of cell death in undifferentiated myoblasts and in differentiated myotubes, because previous studies have indicated that they induced programmed cell death in muscle cells [29, 33, 49]. Cells were treated for 3–6 h with different concentrations of either H2O2 (10 μM – 10 mM) or staurosporine (Stsp: 0.1–0.5 μM) to determine the optimal concentration and time point for further experiments (see Fig. 2). The concentration of H2O2 or staurosporine that induced about a 50–60% cell death in myoblasts was chosen for further experiments (1000 μM H2O2 and 0.5 μM Stsp).

Fig. 2.

Myotubes are more resistant to apoptosis than myoblasts. Myoblasts and myotubes were exposed to H2O2 (a–d) or Stsp (e, f) for 3 h, and the frequency of TUNEL-positive nuclei was counted and displayed (b, d, e, f). Representative pictures of myoblasts (a) and myotubes (c) after treatment with 1000 μM H2O2 indicating a lower number of TUNEL positive nuclei in myotubes. Percentage of TUNEL positive nuclei in myoblasts (b + e) and myotubes (d + f) after treatment with H2O2 (b + d) or Stsp (e + f). Results represented mean ± SE. a, b, c Indicate significant difference between treatments without same letters (P < 0.05). Note the difference in values on y-axis

Terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

The susceptibility to apoptosis was measured in C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes using TUNEL assay according to the manufacturer's recommendations with minor revision (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Pleasanton, CA) after a 3–6 h treatment with different concentrations of either H2O2 (10 μM–10 mM) or staurosporine (Stsp: 0.1–0.5 μM). Briefly, after incubation with apoptosis inducers, myoblasts and differentiated myotubes were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 minutes (min), blocked in 3% H2O2 for 10 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X and 0.1% sodium citrate. Cells were incubated with TUNEL reaction mix diluted 1:3 with dilution buffer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Pleasanton, CA) in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 1 h, followed by incubation with streptavidin-POD enzyme conjugate at 37°C for 30 min. Signal amplification was performed using the tyramide signal amplification system (TSA, Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) at a dilution of 1:200 (TSA fluorescein : amplification buffer) for 30 min as described previously [28]. TUNEL positive nuclei were counted in five separate fields (×200 magnification) using a Zeiss Observer.D1 (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) microscope with GFP filter. Total nuclear number was visualized by Hoechst staining (4 μg/ml) under UV filter. Apoptosis was presented as the percentage of TUNEL positive nuclei compared to total nuclei. Since there are always some undifferentiated cells after differentiation, bright field pictures were used to determine whether nuclei staining positive for TUNEL and Hoechst were inside the myotubes.

Heat shock

Heat shock was induced by placing myoblasts at 60% confluency at 42°C for 6 h followed by 16 h at 37°C. After this period either H2O2 or Stsp were administered for 3 h and cells were assayed for cell viability as described below.

Cell viability

Cell viability was measured using the Trypan Blue exclusion assay. This assay is based on the fact that dead cells take up Trypan blue dye while viable cells exclude the dye. C2C12 cells were plated with 40,000 cells per well on 6 well plates; cells were then treated with H2O2 or StSp for 3 h as described above or treated as control. After incubation, cells were trypsinized, spun down, and resuspended in serum-free DMEM after which 0.4% Trypan Blue (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) was added in a 1:1 dilution for 2 min and the number of viable cells was counted with a hemocytometer. The number of viable cells was expressed as a percentage of controls.

Assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

Δψm was measured as an early event in the initiation of apoptosis, since a decrease of Δψm preceeds leakage of pro-apoptotic proteins involved in caspase-dependent and independent apoptosis from mitochondria into the cytosol. After treatment with H2O2 and StSp, Δψm was assessed using the cationic dye, JC-1 (5,5′, 6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-benzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide), according to the manufacturer's protocol (Biotium, Hayward, CA). In healthy cells the dye stains the cells bright red due to accumulation of the dye within the mitochondria. In apoptotic cells the dye is unable to accumulate within the mitochondria because of the collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential and the dye stains the cells green. The ratio of red divided by green fluorescence is calculated and a decrease in this ratio indicates a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential. C2C12 cells were plated at approximately 60% confluency on 6-well plates and were exposed to 1000 μM H2O2, 0.5 μM StSp or control conditions for 3 h, rinsed with PBS, and followed by incubation with JC-1 reagent 1:100 at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, cells were again rinsed twice with PBS and images were obtained using TRITC (red, 590 nm) and GFP (green, 530 nm) filters on a fluorescent microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer). Care was taken to obtain pictures with identical exposure times and pictures were analyzed using Axio Vision software (Zeiss). The automated measurement program with identical user defined parameters for densitometric and geometric variables was used to determine fluorescent intensity for both filters. The ratio of the sum of intensities of red divided by green fluorescence was determined and expressed as the Δψm index.

Caspase activity determination

Enzymatic activities of caspase-2, -3, -8 and -9 were measured by using caspase specific fluorogenic substrates as described previously [16]. Briefly, after apoptosis treatments, floating and adherent myoblasts or myotubes were collected and lysed in whole lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with leupeptin (1 mg/ml) and PMSF (1 mM) and protein concentrations were determined by a BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). For each reaction, 1 μM of specific caspase substrate including Ac-VDVAD-AMC (caspase-2), Ac-IETD-AMC (caspase-8), Ac-LEHD-AMC (caspase-9) or Ac-DEVD-AMC (caspase-3) was mixed with assay buffer (100 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM DTT, 0.1% CHAPS and 10% sucrose) and equal amounts of protein followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h (all substrates from Peptides International, Louisville, KY). Liberation of free AMC from the fluorogenic substrates (representing caspase activity) was detected by using a Spectra Max fluorescent microplate reader (Molecular Devices), with an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. AMC liberated from the substrates was compared to a standard curve prepared with known amounts of free AMC and the concentration of AMC was calculated.

RNA isolation and assessment of mRNA abundance

Total RNA from C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes was isolated with the RNAqueous Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was treated with DNase (Ambion) and its integrity was checked using Agilent Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA) before measurement of mRNA abundance by real time RT-PCR, as previous described [50]. 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Real time PCR primers were designed using Beacon Designer software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The primers and corresponding mouse mRNAs (gene, forward primer, and reverse primer) investigated in this study were apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC, 5′-CAAGAAGAGGATGAATCTGAAG-3′, 5′-TTGGCAGTAGGTGTCTCG-3′), the 70 kD heat shock protein (HSP70, 5′-GAACTCTTGATGTGTCGTTACTG-3′, 5′-CCGCCTGTCTTAATCTGTGG-3′), 25 kD heat shock protein (HSP25, 5′-AAGGAAGGCGTGGTGGAG-3′, 5′-ACTGCGTGACTGCTTTGG-3′) and myogenin (Myogenin, 5′-ACAATCTGCACTCCCTTACG-3′, 5′-CGTCTGGGAAGGCAACAG-3′). PCR reactions were conducted on iQ5 real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and a SYBRgreen-based protocol was applied, RNA abundance for each gene of interest is normalized to the geometric mean, a factor calculated by GeNorm software (Primer-Design, Southampton, Hants) based on the expression of 18S ribosomal RNA (18S, 5′-AATGAGCCATTCGCAGTTTC-3′, 5′-CTCTGTTCCGCCTAGTCCTG-3′) and ubiquitin C (UBC, 5′-AGGTCAAACAGGAAGACAGACGTA-3′, 5′-TGTGCTTGTTCTTGGGTGTGA-3′) in the same sample as described previously [51].

Subcellular fractionations

Cytosolic and nuclear fractions from myoblasts and myotubes were obtained using the method described by Siu et al. [11]. Briefly, myoblasts and myotubes were homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 20% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM dithiothreitol) and centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected as the cytosolic fractions. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer and 5 M NaCl was added to lyse the nuclei. The mixture was rotated for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant containing the nuclear protein was collected. Purity of the fractions was confirmed with histone and CuZnSOD antibodies for nuclear and cytosolic fractions, respectively.

Western blotting

Western blot analysis of proteins was performed as described previously with minor modifications [28]. Briefly, C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes treated with H2O2 or Stsp were lysed in lysis buffer (see above), which was supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin and 1 μg/ml pepstatin. Protein concentration of the supernatants was determined using the Bradford assay. For determination of apoptosis repressor with CARD domain (ARC), endonuclease G (EndoG), apoptosis inducing factor (AIF), HSP25 and HSP70 protein content, 10–100 μg total protein was loaded and separated on 4–15% acrylamide gradient gel (Bio-Rad), followed by transfer proteins to PVDF membranes with 0.22 μm pore size. Membranes were incubated in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) for 1-h at room temperature followed by incubation with ARC (1:200; ProSci Incorporated, Poway, CA), HSP25 (1:2000; Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth, PA), HSP70 (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), EndoG (1:1000; Cell Signaling), or AIF (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed, and further incubated with highly cross-absorbed infra red-labeled secondary antibodies (1:20,000; Li-Cor) for 20 min at room temperature. Membranes were scanned using Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor) to detect specific antibody binding and quantification. Normalization of bands was performed using β-actin antibody (1:2,000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Statistical analysis

A minimum of three plates was used for each individual condition. Statistical computations were performed using SigmaStat (SSI, Richmond, CA). For comparisons of means between treatments, a one-way or two-way ANOVA was applied where appropriate. In case of significant differences, Tukey multiple comparisons test was used. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

C2C12 muscle cell differentiation and apoptosis

To study the effects of differentiation on myogenic cell apoptosis, C2C12 myogenic cells were used in this study. After 72 h in DM C2C12 cell showed fully formed myotubes (Fig. 1a), exhibited spontaneous twitching in vitro, and showed a more than 100-fold increase in myogenin gene expression (Fig. 1b), indicating full differentiation of the myotubes. H2O2 and Stsp exposure caused morphological changes in myoblasts consistent with apoptosis (Fig. 1d, e). Cells treated with both compounds showed a decrease in cytoplasmic volume, but cells treated with H2O2 also showed a loss of cellular extensions, while Stsp treated cells maintained these extensions. This may indicate that distinct cell death pathways are activated in response to the different compounds.

Fig. 1.

C2C12 differentiation and apoptosis. Representative picture of fully differentiated C2C12 myotubes after 72 h in differentiation medium (a). Myogenin gene expression of myoblast and differentiated myotubes (b). Representative pictures of untreated control C2C12 myoblasts (c), myoblasts undergoing apoptosis induced by 1000 μM H2O2 (d) or 0.5 μM Stsp (e). Values are means ± SE. * Indicates a significant difference from control (P < 0.05)

Differentiated C2C12 are resistant to apoptosis

To investigate the difference in apoptosis susceptibility, proliferating myoblasts and fully differentiated myotubes were exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 or Stsp, followed by a TUNEL assay. The response of myoblasts (Fig. 2a) and myotubes (Fig. 2c) to 1000 μM H2O2 indicates that while a large proportion of myoblasts is TUNEL-positive, nuclei in myotubes are not. When quantified, H2O2 and Stsp treatment resulted in a dose-dependent increase in TUNEL-positive nuclei in myoblasts (Fig. 2a, b and e) as well as myotubes (Fig. 2c, d and f). However, a 6–10-fold lower number of TUNEL positive nuclei were observed in myotubes, compared to myoblasts, at the same concentration of H2O2 and Stsp (compare Fig. 2b–d and e–f) indicating a higher susceptibility to apoptosis in myoblasts than myotubes.

Δψm dissipation is attenuated in differentiated myotubes

One of the earliest events in the progression of apoptosis is the dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and we studied this process in response to H2O2 or Stsp to investigate whether this step in the apoptotic pathway was different between myoblasts and myotubes. JC-1 is a unique cationic dye used to measure the collapse of the electrochemical gradient across the mitochondrial membrane [52]. In healthy untreated (control) cells JC-1 is present as a red fluorescent aggregate in mitochondria (Fig. 3, top panels labeled 590 nm), and in green fluorescent monomeric form in the cytosol (barely visible in top panels labeled 530 nm) in both myoblasts (left two rows) and myotubes (right two rows). Upon the treatment with H2O2 (middle row panels) and Stsp (bottom row panels) there is a dissipation of the Δψm indicated by the increase in staining in the green filter (530 nm) and a decrease in staining in the red filter (590 nm) in myoblasts. In myotubes there is a slight decrease in staining in the red channel, but hardly any increase in the green channel. Quantification of the fluorescent intensities indicated that in myoblasts treated with H2O2 or Stsp the Δψm index decreased significantly while in myotubes only Stsp induced a significant response (Fig. 3 bottom graph). There was a significant main effect between myoblasts and myotubes indicating that the response of myotubes to apoptosis induction is significantly less than that of myoblasts. Therefore, the diminished depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential of myotubes in response to these apoptosis-inducers may be one of the reasons for the lower apoptosis-susceptibility of myotubes.

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) transition is attenuated in myotubes. Untreated (control) or treated (1000 μM H2O2 or 0.5 μM Stsp) C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes were stained with JC-1 and observed under TRITC (590 nm) and GFP (530 nm) filters. Representative pictures are shown in top of figure. Δψm index (represented as the ratio of red to green fluorescence) of control (black bars), 1000 μM H2O2 (light grey bars) or 0.5 μM Stsp (dark grey bars) in myoblasts and myotubes. Values are mean ± SE. # Indicates a significant main effect between myoblasts and myotubes. * Indicates a significant difference compared to control within the cell type (P < 0.05)

Differential activation of caspases in myoblasts and myotubes

We further investigated the activation of caspases, which are key players in the apoptosis process in most mononucleated cells. We suggested that their activity may be associated with the difference in apoptosis susceptibility between myoblasts and myotubes and therefore would be lower in myotubes. Caspase activities of caspase-2, -3, -8 and -9 were measured in cell lysates of myoblasts and myotubes. Contrary to our hypothesis we found that the activities of caspase-2, -3, -8 and -9 were significantly higher in myotubes than in myoblasts (Fig. 4). The activity of caspase-3 was increased more than 10 times in differentiated myotubes compared to myoblasts, suggesting an alternative role for this enzyme in myotubes besides apoptosis, which is supported by the fact that activated caspase-3 is required for efficient myogenic differentiation [45]. To investigate the response of the caspases to apoptosis inducers, H2O2 or Stsp were administered to myoblasts and myotubes (Fig. 5). Activities of caspase-2, -3, -8 and -9 were all increased in response to 1000 μM H2O2 and 0.5 μM Stsp in myotubes, but in myoblasts caspase-2, -3, and -9 were only increased in response to Stsp treatment but not H2O2 (Fig. 5a–d). So, despite the fact that myotubes are resistant to apoptosis, caspases are increased upon induction of apoptosis in myotubes to a greater extent than in myoblasts.

Fig. 4.

High level of caspase activities in differentiated myotubes. Caspase -2, -3, -8 and -9 activities of myoblasts (black bars) and myotubes (grey bars) are depicted. Values are mean ± SE. * Indicates a significant difference compared to myoblasts (P < 0.05)

Fig. 5.

Caspase activation in myoblasts and myotubes following Stsp treatment. Caspase-3 (a), -2 (b), -8 (c) and -9 (d) activities in myoblasts and myotubes treated with H2O2 and Stsp. Units of H2O2 and Stsp are in μM. Values are mean ± SE. * Indicates a significant difference of Stsp compared to corresponding controls. ˆ Indicates a significant difference of H2O2 compared to corresponding controls (P < 0.05)

Enhanced anti-apoptotic mechanisms in differentiated myotubes

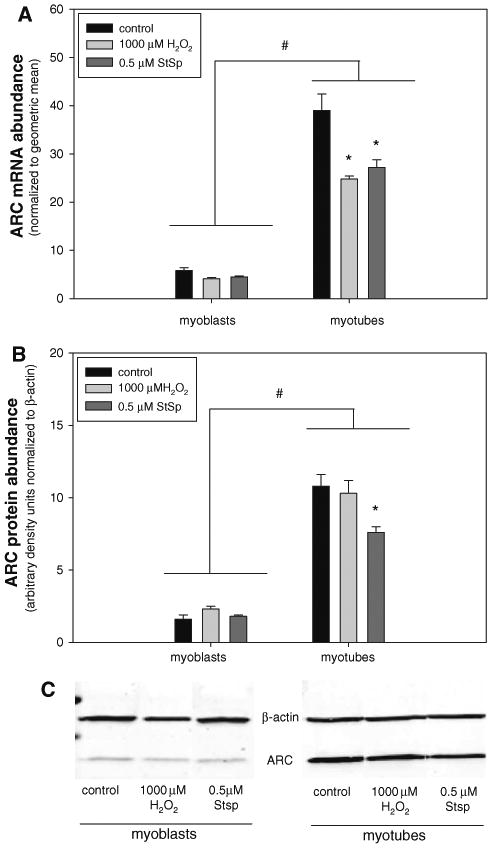

Results above indicate that the increased apoptosis resistance in myotubes can not be simply explained by changes in the activation of caspases in responses to differentiation. We hypothesize that differentiated myotubes may have anti-apoptotic systems in place that inhibit the activated caspases. Therefore, we investigated the status of cell death defense systems that have been suggested to be involved in the protection against oxidative stress- and other pathway-mediated apoptosis [53, 54]. One of these components is muscle-specific apoptosis repressor ARC, which has been shown to block both caspase-dependent and -independent cell death [55]. The gene expression (Fig. 6a) and protein abundance (Fig. 6b, c) of ARC was significantly elevated in myotubes compared to myoblasts as indicated by a main effect between myoblasts and myotubes. Also, H2O2 or Stsp treatment caused a significant decrease in ARC gene expression in myotubes (Fig. 6a), while this effects was not demonstrated in myoblasts. ARC protein abundance was also decreased in response to Stsp in myotubes, but not in myoblasts (Fig. 6b, c).

Fig. 6.

ARC gene expression is highly elevated in myotubes. mRNA (a) and protein abundance (b) and representative immunoblot of Western analysis (c) of ARC in myoblasts and myotubes in response to 1000 μM H2O2 (light grey bars) or 0.5 μM Stsp (dark grey bars) is depicted. Values are means ± SE. # Indicates a significant main effect for myoblasts and myotubes. * Indicates a significant difference from control within myotubes (P < 0.05)

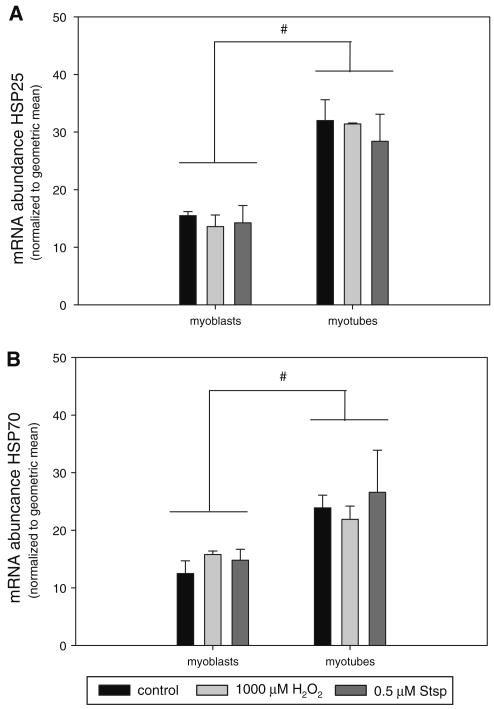

HSPs are regulators of cell death and survival and HSP25 and 70 in particular have been shown to exert their actions mainly through inactivation of caspase activities [56–58]. Therefore, we investigated whether the abundance of these HSPs was different between myoblasts and myotubes. HSP25 (Fig. 7a) and HSP70 (Fig. 7b) mRNA abundance was significantly higher in myotubes than in myoblasts and protein abundance was not detectable in myoblasts while highly abundant in myotubes (Fig. 8a). HSP25 and HSP70 mRNA abundance was not changed in response to apoptosis induction by H2O2 or Stsp. To test whether an increase in HSPs could indeed protect cells from apoptosis we subjected myoblasts to heat shock to induce the expression of HSPs. Indeed HSP25 and HSP70 protein abundance was increased upon exposure to higher temperatures (42°C), but did not reach the level of HSP25 and HSP70 expression in myotubes (Fig. 8a). Myoblasts with increased HSP25 and HSP70 expression were protected from cell death as higher temperature showed a significant main effect in cell survival when H2O2 or Stsp were applied (Fig. 8b). This indicates that increased levels of HSPs have a cell protective effect.

Fig. 7.

Heat shock protein gene expression is elevated in differentiated myotubes. mRNA abundance of HSP27 (a) and HSP70 (b) in myoblasts and myotubes under control conditions (black bars) and after treatment with 1000 μM H2O2 (light grey bars) or 0.5 μM Stsp (dark grey bars) is depicted. Values are means ± SE. # Indicates a significant main effect between myoblasts and myotubes (P < 0.05)

Fig. 8.

Elevated HSP expression enhances cell survival. Representative immunoblots of HSP27 and HSP70 in myoblasts at 37°C and 42°C and of myotubes at 37°C are depicted and compared to β-actin (a). Cell survival of myoblasts at 37°C (black bars) or 42°C (grey bars) under control conditions or after treatment with 1000 μM H2O2 (H2O2) or 0.5 μM Stsp (Stsp) is shown (b). Values are means ± SE. * Indicates significant main effect between 37°C and 42°C (P < 0.05)

Elevated EndoG expression in myotubes

Since the susceptibility to apoptosis and caspase activities did not correlate, we suggested that other mechanisms for the execution of apoptosis may be involved in myotubes and that caspases may play non-apoptotic roles when activated in myotubes. AIF is a caspase-independent death effector and has been linked to muscle cell apoptosis [59]. AIF translocates from mitochondria to nuclei upon induction of cell death and we therefore investigated its abundance in cytosolic and nuclear fractions of myoblasts and myotubes. AIF protein abundance in cytosolic (Fig. 9a) and nuclear (Fig. 9b) fractions was significantly increased in myotubes compared to myoblasts, but no change was observed upon the induction of apoptosis with either H2O2 or Stsp. This indicates that AIF is most likely not involved in the induction of cell death. Previous work has suggested that EndoG, a caspase independent apoptosis inducer, may play a role in muscle cell apoptosis [16, 28]. EndoG, like AIF, is also a mitochondrial protein that is translocated to the nucleus upon apoptosis induction and therefore we investigated its abundance in cytosolic and nuclear fractions. EndoG protein was present at high levels in cytosolic fractions of myotubes (Fig. 10a), but was essentially undetectable in myoblasts (Fig. 10a). EndoG abundance was also barely detectable in the nuclear fraction of either myoblasts or myotubes (Fig. 10b). Interestingly, the protein abundance of EndoG was decreased in the cytosolic fraction of myotubes treated with H2O2 or Stsp indicating that it translocated from this fraction but could still not be detected in the nuclear fraction.

Fig. 9.

AIF protein abundance is elevated in myotubes. AIF protein abundance normalized to β-actin in cytosolic (a) and nuclear (b) fractions of myoblasts and myotubes under control conditions (black bars) or after treatment with 0.5 μM Stsp (light grey bars) or 1000 μM H2O2 (dark grey bars). Representative AIF immunoblot (c) of cytosolic and nuclear fractions of myoblasts and myotubes under control conditions (c) or treated with 0.5 μM Stsp (S) or 1000 μM H2O2 (H). Values are means ± SE. # Indicates a significant main effect between myoblasts and myotubes (P < 0.05)

Fig. 10.

EndoG protein abundance is elevated in myotubes. EndoG protein abundance normalized to β-actin in cytosolic (a) and nuclear (b) fractions of myoblasts and myotubes under control conditions (black bars) or after treatment with 0.5 μM Stsp (light grey bars) or 1000 μM H2O2 (dark grey bars). Representative AIF immunoblot (c) of cytosolic and nuclear fractions of myoblasts and myotubes under control conditions (c) or treated with 0.5 μM Stsp (S) or 1000 μM H2O2 (H). Values are means ± SE. # Indicates a significant main effect between myoblasts and myotubes; * Indicates significant difference from control within cell type (P < 0.05)

Discussion

Differentiated skeletal muscle cells are more resistant to apoptosis than undifferentiated cells [31, 32, 60, 61] and this phenomenon may reflect a mechanism by which the organism can maintain postmitotic muscle cells [34]. How this resistance is conferred is not completely understood. In this study, we found that the apoptosis resistance in myotubes is associated with the elevation of anti-apoptotic proteins, such as ARC and HSPs and that elevation of HSPs reduced myoblast cell death, indicating that these proteins are indeed protective in a muscle environment. We further determined that Δψm dissipation was inhibited in myotubes indicating a protection of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in myotubes.

Potential pathways for apoptosis in muscle cells

The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis begins with the permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane and can be either mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) dependent or independent [62]. Increased permeabilization causes dissipation of the Δψm followed by the release of apoptotic proteins, including cytochrome c, AIF and EndoG [63, 64]. Cytochrome c release induces activation of caspase-9, and subsequent cleavage of caspase-3, which in turn induces apoptosis in most mononucleated cell types. Caspases are thought to be the central proteases responsible for apoptosis and therefore, enhanced resistance to apoptosis such as occurs in myotubes, was expected to be associated with lower caspase activities. Surprisingly, activities of caspase-2, -3, -8 and -9 were all dramatically higher in myotubes, compared to myoblasts, even though apoptosis in response to cell death inducers H2O2 and Stsp was markedly lower in myotubes compared to myoblasts. This indicates that most likely caspases have different functions in differentiated muscle cells compared to undifferentiated muscle cells and other mononucleated cells. Indeed, a number of cellular processes that do not involve apoptosis has been attributed to caspases, such as T-cell activation [65], maintenance of embryonic endothelial cells [66], monocyte, osteogenic and myogenic differentiation [41, 45, 66–68], and fusion of trophoblasts [69]. More importantly, caspase-3 cleavage of muscle specific proteins has been implicated as the initial step in triggering muscle proteolysis during atrophy [70]. Caspases can therefore be viewed as regular signal-transducing molecules which is a phenomenon also suggested by a recent study in which the proteolytic events of caspases were investigated [71]. Even though caspases likely play alternative roles in differentiated myotubes, induction of apoptosis through Stsp in our study still caused a significant increase in caspase-2, -3, -8 and -9 activities even though Δψm dissipation was attenuated compared to myoblasts. Since apoptosis was not increased in the face of these elevated caspase activities, we hypothesized that the anti-apoptotic system in myogenic cells may be strengthened after differentiation. Of interest is the fact that in response to H2O2 caspases did not increase in myoblasts even though cell death is high in these cells. It is possible that these cells undergo a different or additional form of cell death, such as necrosis, and still show DNA fragmentation as shown by the TUNEL assay. Since H2O2 is an inducer of oxidative stress the underlying pathways leading to cell death are likely different than those in response to Stsp and may not involve caspases. Indeed, morphologically the myoblasts treated with H2O2 showed different characteristics than those treated with Stsp. It is also possible that the attenuated response to H2O2 in myotubes is regulated by differential expression of anti-oxidant systems in differentiated cells, but this possibility was not investigated here.

Negative regulators of cell death are elevated in myotubes

Like other vital biological processes, tight regulation of apoptosis is required to ensure a delicate balance of cellular life and death. The resistance to particularly caspase-induced apoptosis in differentiated muscle cells has likely evolved to protect this tissue from accidental loss of cells and/or nuclei due to caspase activation for different processes such as proteolysis. Indeed, several gene families are involved in the negative regulation of apoptosis. In skeletal muscle, for example, cytochrome c release is regulated, in part, by the Bcl-2 family of proteins [72], while inhibitors of apoptosis (IAP) directly suppress activity of caspase-3 and -9 [73]. More recently, a muscle specific anti-apoptotic protein ARC has caused interest because of its extensive anti-apoptotic activity and its links to myogenic differentiation [74]. ARC is an endogenous inhibitor that is thought to target caspase-2 and -8 and plays a role in the mitochondria-mediated pathway by preventing cytochrome c release from mitochondria [75]. We show here that ARC expression in differentiated myotubes is indeed ten times higher than in myoblasts, indicating that this inhibitor may be involved in the apoptosis resistance of myotubes. In addition, ARC may be responsible for the lack of increased caspase activities in response to H2O2 and could therefore be specific in protecting against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, but this possibility needs further investigation. Upon exposure to apoptosis inducers, ARC mRNA abundance decreased in myotubes, as has been shown for protein abundance in response to H2O2 [29]. Also, ARC protein abundance decreased in response to H2O2 in myotubes coinciding with the decrease in Δψm indicating that in myotubes ARC may be an important protective protein for Δψm dissipation.

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are commonly believed to function as a protective mechanism in response to various stressful events including high temperature, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and other cellular damages [76, 77]. In addition, HSPs are known to inhibit apoptosis through caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms [57, 78–84]. We observed that the HSP70 and HSP25 mRNA abundance was significantly elevated in myotubes compared to myoblasts (see also [85]), suggesting that HSPs may play a role in the protection of myotubes from apoptosis in situations where caspase activity is high for different processes, such as differentiation. It has previously been shown that elevated HSPs are protective against calcium- and mitochondrial-related damage in muscle myotubes in vitro [86]. We showed that in myoblasts an elevation of HSPs in response to hyperthermia protected from cell death induced by H2O2 and Stsp, indicating that the enhanced abundance of these proteins in myotubes likely confers a similar cell protective effect.

AIF and EndoG as regulators of apoptosis in myotubes

Caspase-independent pathways for apoptosis have recently been shown to be important in apoptotic nuclear loss in skeletal muscle [28]. EndoG and AIF are two apoptogenic factors released from mitochondria upon apoptotic stimulation, which have been thought to play an important role in regulating apoptosis, associated to disuse or age related muscle atrophy [11, 16, 28]. Since EndoG and AIF are highly elevated in myotubes, we suggest that these molecules may function as apoptosis inducers in differentiated muscle cells where the abundance of molecules capable of inhibiting caspases is very high. AIF, which is capable of DNA fragmentation and subsequent apoptosis [87], was elevated in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of myotubes, but did not change abundance or localization in response to the induction of apoptosis by H2O2 and Stsp, indicating that it is likely not involved in the induction of apoptosis in myotubes. Interestingly, EndoG decreased in the cytosolic fraction of myotubes in response to H2O2 and Stsp indicting that it could be translocated to the nucleus, but our analysis was not sensitive enough to detect this translocation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that myogenic cells develop an apoptosis-resistant phenotype during differentiation that is coincident with the elevation of inhibitors of cell death, such as ARC and HSPs. We propose that these molecules inhibit cell death of muscle cells in the face of elevated apoptotic molecules such as caspases. In addition, the fact that the mitochondrial membrane potential of myotubes is resistant to the induction of apoptosis compared to myoblasts indicates that mechanisms upstream from the mitochondrial membrane dissipation may also play a role in the decreased susceptibility to cell death of myotubes. Moreover, this study suggests that caspase-independent cell death molecules, such as EndoG, may be important for the induction of apoptosis in differentiated muscle cells, but it remains to be determined what mechanisms are underlying the high cell death in myoblasts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Health grant # AG028925 and AR053967.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Rijin Xiao, Division of Physical Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Kentucky, 900 S Limestone, Lexington, KY 40536-0200, USA.

Amy L. Ferry, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Kentucky, 900 S Limestone, Lexington, KY 40536-0200, USA

Esther E. Dupont-Versteegden, Email: eedupo2@uky.edu, Division of Physical Therapy, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Kentucky, 900 S Limestone, Rm 204L, Lexington, KY 40536-0200, USA

References

- 1.Jagani Z, Khosravi-Far R. Cancer stem cells and impaired apoptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;615:331–344. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6554-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melet A, Song K, Bucur O, Jagani Z, Grassian AR, Khosravi-Far R. Apoptotic pathways in tumor progression and therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;615:47–79. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6554-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedlander RM. Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1365–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kermer P, Liman J, Weishaupt JH, Bahr M. Neuronal apoptosis in neurodegenerative diseases: from basic research to clinical application. Neurodegener Dis. 2004;1:9–19. doi: 10.1159/000076665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams V, Jiang H, Yu J, et al. Apoptosis in skeletal myocytes of patients with chronic heart failure is associated with exercise intolerance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:959–965. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tews DS. Muscle-fiber apoptosis in neuromuscular diseases. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:443–458. doi: 10.1002/mus.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukasa T, Momoi T, Momoi MY. Activation of caspase-3 apoptotic pathways in skeletal muscle fibers in laminin alpha2-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:139–142. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tidball JG, Albrecht DE, Lokensgard BE, Spencer MJ. Apoptosis precedes necrosis of dystrophin-deficient muscle. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 6):2197–2204. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin WA, Bergamin N, Sabatelli P, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in myopathic mice with collagen VI deficiency. Nat Genet. 2003;35:367–371. doi: 10.1038/ng1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirks A, Leeuwenburgh C. Apoptosis in skeletal muscle with aging. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R519–R527. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00458.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siu PM, Pistilli EE, Butler DC, Alway SE. Aging influences the cellular and molecular responses of apoptosis to skeletal muscle unloading. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C338–C349. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00239.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strasser H, Tiefenthaler M, Steinlechner M, Eder I, Bartsch G, Konwalinka G. Age dependent apoptosis and loss of rhabdosphincter cells. J Urol. 2000;164:1781–1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith HK, Maxwell L, Martyn JA, Bass JJ. Nuclear DNA fragmentation and morphological alterations in adult rabbit skeletal muscle after short-term immobilization. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;302:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s004410000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupont-Versteegden EE, Murphy RJ, Houle JD, Gurley CM, Peterson CA. Activated satellite cells fail to restore myonuclear number in spinal cord transected and exercised rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C589–C597. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.3.C589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupont-Versteegden EE. Apoptosis in skeletal muscle and its relevance to atrophy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7463–7466. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leeuwenburgh C, Gurley CM, Strotman BA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Age-related differences in apoptosis with disuse atrophy in soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1288–R1296. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00576.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen DL, Linderman JK, Roy RR, et al. Apoptosis: a mechanism contributing to remodeling of skeletal muscle in response to hindlimb unweighting. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C579–C587. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallegly JC, Turesky NA, Strotman BA, Gurley CM, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Satellite cell regulation of muscle mass is altered at old age. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1082–1090. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borisov AB, Carlson BM. Cell death in denervated skeletal muscle is distinct from classical apoptosis. Anat Rec. 2000;258:305–318. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000301)258:3<305::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruusgaard JC, Gundersen K. In vivo time-lapse microscopy reveals no loss of murine myonuclei during weeks of muscle atrophy. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1450–1457. doi: 10.1172/JCI34022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupont-Versteegden EE. Apoptosis in muscle atrophy: relevance to sarcopenia. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alway SE, Siu PM. Nuclear apoptosis contributes to sarcopenia. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008;36:51–57. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e318168e9dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semsarian C, Wu MJ, Ju YK, et al. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy is mediated by a Ca2+-dependent calcineurin signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;400:576–581. doi: 10.1038/23054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JE. The satellite cell as a companion in skeletal muscle plasticity: currency, conveyance, clue, connector and colander. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:2276–2292. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell PO, Pavlath GK. A muscle precursor cell-dependent pathway contributes to muscle growth after atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1706–C1715. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.5.C1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jejurikar SS, Kuzon WM., Jr Satellite cell depletion in degenerative skeletal muscle. Apoptosis. 2003;8:573–578. doi: 10.1023/A:1026127307457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jejurikar SS, Henkelman EA, Cederna PS, Marcelo CL, Urbanchek MG, Kuzon WM., Jr Aging increases the susceptibility of skeletal muscle derived satellite cells to apoptosis. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:828–836. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dupont-Versteegden EE, Strotman BA, Gurley CM, et al. Nuclear translocation of EndoG at the initiation of disuse muscle atrophy and apoptosis is specific to myonuclei. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1730–R1740. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00176.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siu PM, Wang Y, Alway SE. Apoptotic signaling induced by H2O2-mediated oxidative stress in differentiated C2C12 myotubes. Life Sci. 2009;84:468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gil J, Stembalska A, Pesz KA, Sasiadek MM. Cancer stem cells: the theory and perspectives in cancer therapy. J Appl Genet. 2008;49:193–199. doi: 10.1007/BF03195612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh K. Coordinate regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis during myogenesis. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 1997;3:53–58. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5371-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Walsh K. Resistance to apoptosis conferred by Cdk inhibitors during myocyte differentiation. Science. 1996;273:359–361. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camara Y, Duval C, Sibille B, Villarroya F. Activation of mitochondrial-driven apoptosis in skeletal muscle cells is not mediated by reactive oxygen species production. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latella L, Lukas J, Simone C, Puri PL, Bartek J. Differentiation-induced radioresistance in muscle cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6350–6361. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6350-6361.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith MI, Huang YY, Deshmukh M. Skeletal muscle differentiation evokes endogenous XIAP to restrict the apoptotic pathway. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernando P, Megeney LA. Is caspase-dependent apoptosis only cell differentiation taken to the extreme? FASEB J. 2007;21:8–17. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5912hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrido C, Kroemer G. Life's smile, death's grin: vital functions of apoptosis-executing proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosado JA, Lopez JJ, Gomez-Arteta E, Redondo PC, Salido GM, Pariente JA. Early caspase-3 activation independent of apoptosis is required for cellular function. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:142–152. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwerk C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Non-apoptotic functions of caspases in cellular proliferation and differentiation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1453–1458. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mogi M, Togari A. Activation of caspases is required for osteoblastic differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47477–47482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miura M, Chen XD, Allen MR, et al. A crucial role of caspase-3 in osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1704–1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI20427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rohn TT, Cusack SM, Kessinger SR, Oxford JT. Caspase activation independent of cell death is required for proper cell dispersal and correct morphology in PC12 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernando P, Brunette S, Megeney LA. Neural stem cell differentiation is dependent upon endogenous caspase 3 activity. FASEB J. 2005;19:1671–1673. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2981fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oomman S, Strahlendorf H, Finckbone V, Strahlendorf J. Non-lethal active caspase-3 expression in Bergmann glia of postnatal rat cerebellum. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;160:130–145. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernando P, Kelly JF, Balazsi K, Slack RS, Megeney LA. Caspase 3 activity is required for skeletal muscle differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11025–11030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162172899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weil M, Raff MC, Braga VM. Caspase activation in the terminal differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes. Curr Biol. 1999;9:361–364. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larsen BD, Rampalli S, Burns LE, Brunette S, Dilworth FJ, Megeney LA. Caspase 3/caspase-activated DNase promote cell differentiation by inducing DNA strand breaks. PNAS. 2010;107:4230–4235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913089107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor JM, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Davies JD, et al. A role for the ETS domain transcription factor PEA3 in myogenic differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5550–5558. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stangel M, Zettl UK, Mix E, et al. H2O2 and nitric oxide-mediated oxidative stress induce apoptosis in rat skeletal muscle myoblasts. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:36–43. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao R, Su Y, Simmen RC, Simmen FA. Dietary soy protein inhibits DNA damage and cell survival of colon epithelial cells through attenuated expression of fatty acid synthase. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G868–G876. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00515.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dupont-Versteegden EE, Nagarajan R, Beggs ML, Bearden ED, Simpson PM, Peterson CA. Identification of cold-shock protein RBM3 as a possible regulator of skeletal muscle size through expression profiling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1263–R1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90455.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galluzzi L, Zamzami N, de La Motte Rouge T, Lemaire C, Brenner C, Kroemer G. Methods for the assessment of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:803–813. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garrido C, Gurbuxani S, Ravagnan L, Kroemer G. Heat shock proteins: endogenous modulators of apoptotic cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:433–442. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ekhterae D, Lin Z, Lundberg MS, Crow MT, Brosius FC, III, Nunez G. ARC inhibits cytochrome c release from mitochondria and protects against hypoxia-induced apoptosis in heart-derived H9c2 cells. Circ Res. 1999;85:e70–e77. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nam YJ, Mani K, Wu L, et al. The apoptosis inhibitor ARC undergoes ubiquitin-proteasomal-mediated degradation in response to death stimuli: identification of a degradation-resistant mutant. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5522–5528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takayama S, Reed JC, Homma S. Heat-shock proteins as regulators of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:9041–9047. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voss OH, Batra S, Kolattukudy SJ, Gonzalez-Mejia ME, Smith JB, Doseff AI. Binding of caspase-3 prodomain to heat shock protein 27 regulates monocyte apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-3 proteolytic activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25088–25099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmitt E, Parcellier A, Gurbuxani S, et al. Chemosensitization by a non-apoptogenic heat shock protein 70-binding apoptosis-inducing factor mutant. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8233–8240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siu PM, Pistilli EE, Alway SE. Apoptotic responses to hindlimb suspension in gastrocnemius muscles from young adult and aged rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1015–R1026. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00198.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mercier I, Vuolo M, Madan R, et al. ARC, an apoptosis suppressor limited to terminally differentiated cells, is induced in human breast cancer and confers chemo- and radiation-resistance. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:682–686. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mercer SE, Ewton DZ, Deng X, Lim S, Mazur TR, Friedman E. Mirk/Dyrk1B mediates survival during the differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25788–25801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413594200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marzetti E, Hwang JC, Lees HA, et al. Mitochondrial death effectors: relevance to sarcopenia and disuse muscle atrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341(Pt 2):233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chun HJ, Zheng L, Ahmad M, et al. Pleiotropic defects in lymphocyte activation caused by caspase-8 mutations lead to human immunodeficiency. Nature. 2002;419:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang TB, Ben-Moshe T, Varfolomeev EE, et al. Caspase-8 serves both apoptotic and nonapoptotic roles. J Immunol. 2004;173:2976–2984. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sordet O, Rebe C, Plenchette S, et al. Specific involvement of caspases in the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages. Blood. 2002;100:4446–4453. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murray TV, McMahon JM, Howley BA, et al. A non-apoptotic role for caspase-9 in muscle differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3786–3793. doi: 10.1242/jcs.024547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Black S, Kadyrov M, Kaufmann P, Ugele B, Emans N, Huppertz B. Syncytial fusion of human trophoblast depends on caspase 8. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:90–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Du J, Wang X, Miereles C, et al. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:115–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dix MM, Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Global mapping of the topography and magnitude of proteolytic events in apoptosis. Cell. 2008;134:679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: a primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roy N, Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases. EMBO J. 1997;16:6914–6925. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunter AL, Zhang J, Chen SC, et al. Apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) inhibits myogenic differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koseki T, Inohara N, Chen S, Nunez G. ARC, an inhibitor of apoptosis expressed in skeletal muscle and heart that interacts selectively with caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5156–5160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parcellier A, Gurbuxani S, Schmitt E, Solary E, Garrido C. Heat shock proteins, cellular chaperones that modulate mitochondrial cell death pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00623-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Locke M, Noble EG, Tanguay RM, Feild MR, Ianuzzo SE, Ianuzzo CD. Activation of heat-shock transcription factor in rat heart after heat shock and exercise. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C1387–C1394. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.6.C1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gorman AM, Szegezdi E, Quigney DJ, Samali A. Hsp27 inhibits 6-hydroxydopamine-induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis in PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Samali A, Robertson JD, Peterson E, et al. Hsp27 protects mitochondria of thermotolerant cells against apoptotic stimuli. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:49–58. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0049:hpmotc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bruey JM, Ducasse C, Bonniaud P, et al. Hsp27 negatively regulates cell death by interacting with cytochrome c. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:645–652. doi: 10.1038/35023595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ravagnan L, Gurbuxani S, Susin SA, et al. Heat-shock protein 70 antagonizes apoptosis-inducing factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:839–843. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kamradt MC, Chen F, Sam S, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis during myogenic differentiation by inhibiting caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38731–38736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kamradt MC, Lu M, Werner ME, et al. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin is a novel inhibitor of TRAIL-induced apoptosis that suppresses the activation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11059–11066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ikeda R, Yoshida K, Ushiyama M, et al. The small heat shock protein alphaB-crystallin inhibits differentiation-induced caspase 3 activation and myogenic differentiation. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1815–1819. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ito H, Kamei K, Iwamoto I, Inaguma Y, Kato K. Regulation of the levels of small heat-shock proteins during differentiation of C2C12 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;266:213–221. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maglara AA, Vasilaki A, Jackson MJ, McArdle A. Damage to developing mouse skeletal muscle myotubes in culture: protective effect of heat shock proteins. J Physiol. 2003;548:837–846. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]