Abstract

Uncuffed endotracheal tubes traditionally have been preferred over cuffed endotracheal tubes in young pediatric patients. However, recent evidence in elective pediatric surgical populations suggests otherwise. Because young pediatric burn patients can pose unique airway and ventilation challenges, we reviewed adverse events associated with the perioperative use of cuffed and uncuffed endotracheal tubes. We retrospectively reviewed 327 cases of operating room endotracheal intubation for general anesthesia in burned children 0–10 years of age over a 10-year period. Clinical airway outcomes were compared using multivariable logistic regression, controlling for relevant patient and injury characteristics. Compared to those receiving cuffed tubes, children receiving uncuffed tubes were significantly more likely to demonstrate clinically significant loss of tidal volume (odds ratio 10.62, 95% confidence interval 2.2–50.5) and require immediate reintubation to change tube size/type (odds ratio 5.54, 95% confidence interval 2.1–13.6). No significant differences were noted for rates of post-extubation stridor. Our data suggest that operating room use of uncuffed endotracheal tubes in such patients is associated with increased rates of tidal volume loss and reintubation. Due to the frequent challenge of airway management in this population, strategies should emphasize cuffed endotracheal tube use that is associated with lower rates of airway manipulation.

Keywords: Pediatric, Intubation, Burn, Cuffed, Uncuffed

1. Introduction

Although cuffed endotracheal tubes (CETTs) are considered standard care in adults requiring an artificial airway, protocols for perioperative airway management have traditionally discouraged the use of CETTs in children less than 10 years of age, in favor of uncuffed endotracheal tubes (UETTs) [1,2]. This recommendation stems from historical concerns that ill-fitting or poorly designed CETTs may cause tissue damage to the larynx and airway mucosa, resulting in subglottic stenosis [3]. However, this decades-long dogma has been challenged by studies of non-burn-injured pediatric patients in the elective surgery [4] and critical care [5,6] settings. These studies reported that modern high-volume, low-pressure CETTs prevent unintended loss of tidal volume (“air leak”) around the endotracheal tube, enhance control of anesthetic gas flow in the operating room, improve oxygenation and ventilation, and diminish risks of aspiration, airway injury, and infection. Furthermore, they report no increased risk of subglottic tracheal injury with CETTs compared to UETTs. Despite these findings, many hospitals continue to predominately use UETTs in children [7].

Conventional arguments in favor of UETT use in young children include (1) the unique laryngeal anatomy in children that allows for adequate tube fit that prevents aspiration without a cuff, (2) cuffs increase external tube diameter and necessitate use of tubes with smaller internal diameter, creating greater airway resistance, (3) cuff pressures must be carefully monitored to prevent overinflation injury by CETTs, (4) cuff abrasion/ischemia of the airway mucosa may lead to tracheal injury and subsequent stenosis, and (5) the margin of safety for avoiding mainstem bronchus intubation is greater for UETT placement than for CETT placement due to cuff proximity to the distal end of the tube [8]. Conversely, CETTs have demonstrated several distinct advantages, as they (1) reduce the risk of aspiration [9], (2) allow modern ventilators to monitor lung function (e.g., tidal volume, lung compliance) more effectively by preventing air leak around the tube, (3) less often require exchange due to a too small size, (4) allow for more accurate manipulation of inhalational gas concentration, and (5) reduce environmental contamination with anesthetic gas [10].

Previous investigations of CETT and UETT use for general anesthesia in the operating room setting have focused on elective pediatric surgical populations [4], and did not address the special issues present in pediatric burn patients. These children often must undergo multiple endotracheal intubations for repeated skin grafting and reconstructive surgeries performed under general anesthesia. They may have concomitant smoke inhalation injury and can present anatomic challenges to many aspects of airway management. Direct laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation are often more challenging in burned children due to the distortion of soft tissue and airway anatomy that may occur unpredictably as a result of the initial injury, extensive fluid resuscitation, associated smoke inhalation injury, or previous burn excision/grafting to the face/neck [11]. These airway management issues disproportionally affect young pediatric patients in whom a relatively small amount of edema can substantially narrow their already anatomically small airway [12]. Limited mouth opening and neck range of motion due to scar contractures occurring later in the healing process can also complicate laryngoscopy and endotracheal tube placement. For these reasons, airway management of pediatric burn patients merits special attention and research specifically focused on clinical practices that will limit the number of endotracheal tube placement attempts, due to their associated risks.

A case series published in 2006 documented five cases of intubated pediatric burn patients who required emergency reintubation with a CETT because of life-threatening inadequate ventilation with the initially placed UETT [13]. However, large scale, quantitative studies of endotracheal tube type have not been performed in the young pediatric burn population, yet are necessary to help clarify appropriate clinical practices. Because the majority of burned children undergoing surgery require endotracheal intubation only during the immediate perioperative period, we chose to study this uniquely vulnerable population that could potentially benefit from the identification of evidence-based protocols for optimal perioperative airway management. This study sought to evaluate current practices by comparing the rates of adverse events associated with the use of CETTs and UETTs in a large population of burn-injured children undergoing general anesthesia in the operating room.

2. Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective review was conducted of all patients between the ages of 0–10 years who were admitted to our regional burn center and underwent endotracheal intubation in the operating room over a 10-year period between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2007. Medical records were identified from the regional burn center registry, with data abstraction for patient demographics (age and gender), burn severity, endotracheal intubation characteristics (number of attempts, tube size [internal diameter in mm], cuffed vs. uncuffed tube), adverse events related to endotracheal intubation (misplaced tube, clinically significant leak, failed extubation, immediate reintubation, etc.), and complications (self-extubation, pneumonia, stridor, etc.). We excluded cases where a postoperative stay in the intensive care unit with continued intubation was required, and those without a documented tube type.

We defined a clinically significant air leak as any air leak around an endotracheal tube that was noted in the records AND resulted in difficulty maintaining ventilation or necessitated a tube change. Immediate reintubation was defined as intentional and immediate endotracheal tube removal and replacement occurring subsequent to the initial intubation, for any reason. Clinical decisions that determined tube size and tube type were at the discretion of each anesthesia team, consisting of an attending anesthesiologist and either a resident or certified nurse anesthetist.

We included variables in multivariable analytic models based on an a priori assessment of clinical relevance. We categorized burn severity based on total body surface area (TBSA) into three groups (TBSA < 20%, TBSA 20–49%, TBSA ≥ 50%). We also included gender, age, calendar year of intubation, and burns to the head/neck or face as potential confounders. Our two main dependent variables were (1) clinically significant air leak and (2) immediate reintubation, representing separable observations or events that impacted clinical care. The primary independent variable was tube type (cuffed vs. uncuffed). Univariate and bivariate analyses were completed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square testing for categorical variables. To identify significant associations between tube type and outcomes, we performed separate logistic regressions with each of our dependent variables (immediate reintubation and air leak), using tube type as the dependent variable, and the independent and control variables described above. Odds ratios are presented for explanatory variables, with p-values and 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

Over this 10-year period, 327 children underwent endotracheal intubations performed in the burn operating room setting – 111 with CETTs, 117 with UETTs, and 99 in which tube type could not be determined retrospectively. Thus, our final data set included the 228 intubation events involving CETTs and UETTs, occurring in 145 patients. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the two groups. Cuffed tubes were used more frequently in patients 5 years and older, females, and patients with a burn size of less than 20% TBSA, while uncuffed tubes were used more frequently in patients less than 5 years of age, males, and those with a TBSA of greater than 20%. Over the course of the 10-year study period, a significant increase in the use of CETTs relative to UETTs was noted with 77.9% of the total UETT intubations and 29.4% of the CETT intubations occurring in the first 5 years of the study (Table 1). We found no significant differences in outcomes or demographics between patients for whom the tube cuff status was known and cases where these details were unreported.

Table 1.

Patient and burn characteristics.

| Cuffed (111) |

Uncuffed (117) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 24.3% | 37.6% | 0.03 |

| Age (mean years) | 4.6 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| <1 | 3.6% | 23.1% | |

| 1–4 | 53.2% | 53.0% | |

| 5–10 | 43.2% | 23.9% | |

| Mean TBSA | 22.1 | 14.4 | <0.001 |

| TBSA <20% | 48.7% | 75.2% | |

| TBSA 20–49.9% | 35.1% | 18.8% | |

| TBSA ≥ 50% | 16.2% | 6.0% | |

| Facial burn present | 35.1% | 35.0% | NS |

| Smoke inhalation present | 5.4% | 3.5% | NS |

| Any immediate reintubation required | 7.2% | 37.6% | <0.001 |

| Air leak | 1.8% | 23.1% | <0.001 |

| Year of intubation | <0.001 | ||

| 1998–2002 | 29.4% | 77.9% | |

| 2003–2007 | 70.6% | 22.1% |

NS: not statistically significant, p > 0.05. TBSA: total body surface area burned.

Adverse outcomes occurred infrequently with statistically insignificant differences between groups, including post-extubation stridor (4.3% vs. 7.2% for UETT and CETT groups, respectively), self-extubation (0.9% in both groups), aspiration (no cases in either group), and failed extubation (3.4% vs. 1.8% for UETT and CETT groups, respectively).

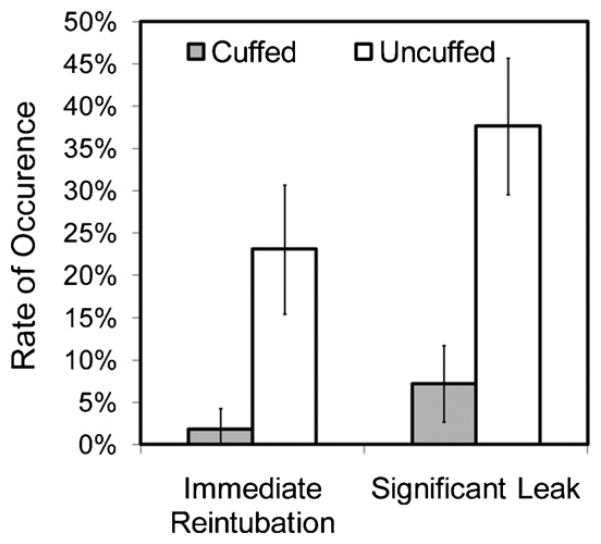

With respect to the complication of air leak, providers reported 29 clinically significant air leaks, all of which led to immediate reintubations. Two such air leaks occurred with CETTs (1.8% of all CETTs), while 27 air leaks (23.1% of all UETTs) were reported with UETTs (p < 0.001, see Fig. 1). Using multivariable logistic regression to control for age, gender, TBSA, year of intubation, and presence of burn to the face, we observed a significant association between clinically significant air leaks and the use of UETTs, compared to CETTs, with an odds ratio of 10.62 (95% CI 2.2–50.5, p = 0.003, see Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Rates of immediate reintubation and clinically significant air leak in pediatric burn patients intubated with cuffed and uncuffed endotracheal tubes. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Factors associated with a clinically significant air leak.

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intubation tube type | |||

| Cuffed | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Uncuffed | 10.63 | 2.24–50.5 | 0.003 |

| Age (years) | |||

| <1 | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| 1–4 | 1.56 | 0.45–5.42 | NS |

| 5–10 | 1.70 | 0.46–6.34 | NS |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Female | 0.75 | 0.28–2.01 | NS |

| Burn severity (TBSA) | |||

| <20% | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| 20–49.9% | 0.44 | 0.24–2.40 | NS |

| ≥50% | 1.15 | 0.22–7.51 | NS |

| Facial burn | 0.74 | 0.23–1.72 | NS |

| Year of intubation | 0.75 | 0.60–0.922 | 0.007 |

NS: not statistically significant, p > 0.05. TBSA: total body surface area burned.

With respect to the need for reintubation, a total of 52 immediate reintubations were reported, of which 8 occurred in patients with cuffed tubes and 44 occurred in those with uncuffed tubes (Fig. 1). Controlling for the same factors as above, immediate reintubations occurred significantly more often with the use UETTs, compared to CETTs, with an odds ratio of 5.54 (95% CI 2.1–13.6, p < 0.001, see Table 3). Changes in tube size were the most common reason for reintubation (34), while others involved changes from UETTs to CETTs of the same size (7). The distribution of these tube changes after initial use of a cuffed or uncuffed tube is described in Table 4.

Table 3.

Factors associated with immediate reintubation.

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intubation tube type | |||

| Cuffed | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Uncuffed | 5.37 | 2.12–13.59 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | |||

| <1 | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| 1–4 | 2.28 | 0.82–6.36 | NS |

| 5–10 | 1.83 | 0.62–5.44 | NS |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Female | 0.85 | 0.40–1.83 | NS |

| Burn severity (TBSA) | |||

| <20% | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| 20–49.9% | 0.86 | 0.37–2.04 | NS |

| ≥50% | 0.34 | 0.06–1.82 | NS |

| Facial burn | 1.30 | 0.62–2.77 | NS |

| Year of intubation | 0.81 | 0.70–0.94 | 0.006 |

NS: not statistically significant, p > 0.05. TBSA: total body surface area burned.

Table 4.

Immediate reintubation tube size and cuff status changes.

| Tube type | Change | Number of events |

|---|---|---|

| Uncuffed | Total | 44 |

| Increased diameter | 20 | |

| Decreased diameter | 13 | |

| To cuffed (same size) | 6 | |

| Unknown change | 5 | |

| Cuffed | Total | 8 |

| Increased diameter | 1 | |

| Decreased diameter | 0 | |

| To uncuffed (same size) | 1 | |

| Unknown change | 6 | |

| Unknown | Total | 8 |

Internal tube diameters were used for comparison.

When the sample was restricted to infants (ages 0–2), similar associations were observed, including more frequent immediate reintubations in UETT than in CETT patients (odds ratio 10.0, 95% CI 2.1–48.5, p = 0.004). No leaks occurred in the infant CETT group (0 out of 33), while 13 (19.4%) of the 67 infants in the UETT group experienced significant air leaks. With no leaks in the CETT group, an odds ratio cannot be calculated.

4. Discussion

Our data demonstrate that compared to UETTs, the use of CETTs for endotracheal intubation of pediatric burn patients ages 0–10 years undergoing general anesthesia while in the operating room is associated with reduced rates of both clinically significant air leak and immediate reintubation. Steady increases in the use of CETTs for pediatric endotracheal intubation were observed in our burn center over the 10-year study period, and CETTs have recently become the standard of care in many [5], but not all [7] hospitals.

The most likely explanations for this change in practice are the ease of use and the safety associated with CETTs. While UETTs have a fixed outer diameter and must be sized precisely to form a secure fit within the cricoid ring (to prevent both excessive tidal volume leak and aspiration), the outer diameter of modern high-volume, low-pressure CETTs may be adjusted by gentle cuff inflation to seal such leaks, while placing minimal pressure on the tracheal mucosa. Thus, improperly fitted UETTs are more likely to result in physiologic complications (e.g., hypoventilation, hypercarbia, hypoxemia) that in most cases cannot be rectified without repeat laryngoscopy and reintubation. Repeat laryngoscopy and reintubation exposes patients to additional risks for procedural complications (e.g., dental injury, laryngospasm, arytenoid or vocal cord injury, tracheal lacerations and oropharyngeal tissue trauma) [14,15] that are arguably more problematic in small burned children for the anatomic and burn-related reasons described above. In our retrospective sample, however, these adverse intubation-related outcomes could not be determined, so we were unable to confirm whether patients undergoing multiple intubations were at increased risk for these complications.

A previous, large, randomized, prospective, controlled trial in children ages 0–8 years receiving general anesthesia for a variety of elective surgical procedures reported the incidence of immediate reintubation to be 1.2% and 23% for CETTs and UETTs, respectively, compared with rates of 7.2% and 37.6% found in our burned population [4]. The higher reintubation rates in our study may reflect the increased incidence of airway edema (necessitating reintubation with a smaller tube or decreased lung compliance requiring high lung inflation pressures that can lead to increased air leak around a too small tube) that are frequently present in burned patients due to concomitant smoke inhalation injury and/or large volume fluid resuscitation.

All clinically significant air leaks in our study population resulted in immediate reintubation. In the most common scenario, initial placement of an ill-fitting UETT (including observation of a large air leak and inadequate ventilation) led to the replacement of the UETT with either a larger UETT or a CETT. In addition to problems with inadequate positive-pressure ventilation, tidal volume losses observed with UETTs have also been associated with elevated levels of anesthetic gas contamination in the operating room [4]. However, we were unable to assess this outcome in our retrospective design.

An increased rate of post-extubation stridor has been cited as one justification for avoiding CETT use in young children [1,2], but more recent studies suggested otherwise. Newth et al. reported no difference in rates of post-extubation stridor in pediatric intensive care units for CETTs and UETTs, with an overall rate of 5.8%. We also observed no difference in post-extubation stridor rates between children with CETTs and UETTs [5], with an overall rate of 6.1% in the burn surgery setting. Consistent with the hypothesis that this complication is associated with the duration of intubation [16], one might expect its incidence to be lower in our sample of short-term intubations. However, as noted above, burn-injured patients may have increased airway edema and be at increased risk for post-extubation stridor [17]. In addition, a larger sample size is needed to adequately compare stridor incidence after short-term use of CETTs and UETTs.

As a retrospective review, our study has several important limitations. The retrospective study design provides limited clinical detail that might allow a more comprehensive analysis of the factors that affect airway management in this special population. Rates of CETT vs. UETT use changed over the 10-year study period, leaving the possibility for evolving practices to account for some of the difference in air leak and immediate reintubation rates. However, the logistic regression model reported above attempts to limit this effect by controlling for year of intubation. Future studies involving a larger study population would allow for comparison of less frequent complications such as post-extubation stridor and aspiration across CETT and UETT groups in this highly selected population. While this study focused on short-term intubations in the operating room setting, a comparison of CETTs and UETTs for long-term intubation and ventilation in the pediatric burn intensive care population is still needed.

Our study has shown that CETTs may have utility as a safer alternative to UETTs in burn-injured children and infants in the perioperative setting. CETTs reduced the occurrence of clinically significant air leaks that can result in hypoventilation and poor gas exchange. CETTs also were associated with a decreased need for repeat laryngoscopy and reintubation, offering the benefit of reduced risk associated with potentially demanding airway management procedures in this population. Given these advantages and the unique airway management challenges associated with pediatric burn injuries, CETTs should be strongly considered for optimal airway management for children in this perioperative setting.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded, in part, by the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society's Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship, the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research Medical Student Anesthesia Research Fellowship, the David and Nancy Auth-Washington Research Foundation Endowment, and the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR, 1KL2RR025015-01). Sponsors had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the American Burn Association 41st Annual Meeting in San Antonio, TX in March 2009.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisher DM. Anesthesia equipment for pediatrics. In: Gregory GA, editor. Pediatr Anesth. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 2001. pp. 207–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motoyama EK. Endotracheal intubation. In: Motoyama EK, Davis PJ, editors. Smith's anesthesia for infants and children. 5th ed. C.V. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1990. pp. 269–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calhoun K. Long-term airway sequelae in a pediatric burn population. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:721–5. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khine H. Comparison of cuffed and uncuffed endotracheal tubes in young children during general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1997;86(3):627–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199703000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newth CJL, Rachman B, Patel N, Hammer J. The use of cuffed versus uncuffed endotracheal tubes in pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 2004;144:333–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deakers TW, Reynolds G, Stretton M, Newth CJL. Cuffed endotracheal tubes in pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 1994;125:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn PE, Black AE, Mitchell V. The use of cuffed tracheal tubes for pediatric tracheal intubation, a survey of specialty practice in the United Kingdom. Eur J Anesthesiol. 2008;25:685–8. doi: 10.1017/S0265021508003839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss M, Dullenkopf A, Gysin C, Dillier CM, Gerber AC. Shortcomings of cuffed paediatric tracheal tubes. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:78–88. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browning DH, Graves SA. Incidence of aspiration with endotracheal tubes in children. J Pediatr. 1983;102:582–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Part 12: pediatric advanced life support. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl. 24):IV-167–87. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan RL. Airway management and respiratory care of the burn patient. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2000;38(3):129–45. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotta AT, Wiryawan B. Respiratory emergencies in children. Resp Care. 2003;48(3):248–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheridan R. Uncuffed endotracheal tubes should not be used in seriously burned children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7(3):258–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000216681.71594.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner ME, Benenfeld SM, Warner MA, Schroeder DR, Maxson PM. Perianesthetic dental injuries: frequency, outcomes, and risk factors. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(5):1302–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domino KB. Closed malpractice claims for airway trauma during anesthesia. ASA Newslett. 1998;62(6):10–1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi VV. Acute lesions induced by endotracheal intubation: occurrence in the upper respiratory tract of newborn infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1972;124:646–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1972.02110170024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemper KJ, Benson MS, Bishop MJ. Predictors of postextubation stridor in pediatric trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:352–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]