Abstract

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is the rate-limiting enzyme in the catabolism of heme, followed by production of biliverdin, free iron and carbon monoxide (CO). HO-1 is a stress-responsive protein induced by various oxidative agents. Recent studies demonstrate that the expression of HO-1 in response to different inflammatory mediators may contribute to the resolution of inflammation and has protective effects in several organs against oxidative injury. Although the mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory actions of HO-1 remains poorly defined, both CO and biliverdin/bilirubin have been implicated in this response. In the gastrointestinal tract, HO-1 is shown to be transcriptionally induced in response to oxidative stress, preconditioning and acute inflammation. Recent studies suggest that the induction of HO-1 expression plays a critical protective role in intestinal damage models induced by ischemia-reperfusion, indomethacin, lipopolysaccharide-associated sepsis, trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid, and dextran sulfate sodium, indicating that activation of HO-1 may act as an endogenous defensive mechanism to reduce inflammation and tissue injury in the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, CO derived from HO-1 is shown to be involved in the regulation in gastro-intestinal motility. These in vitro and in vivo data suggest that HO-1 may be a novel therapeutic target in patients with gastrointestinal diseases.

Keywords: Bach1, bilirubin, carbon monoxide, heme oxygenase, indomethacin, Nrf2, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Heme oxygenase (HO) is the rate-limiting enzyme in heme catabolism, a process which leads to the generation of equimolar amounts of biliverdin, free iron and carbon monoxide (CO).(1) Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is highly inducible by a vast array of stimuli, including oxidative stress, heat shock, ultraviolet radiation, ischemia-reperfusion, heavy metals, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), cytokines, nitric oxide (NO), and its substrate, heme.(2) Heme oxygenae-2 (HO-2) is a constitutive gene, expressed in neurons, endothelium and many other cell types. Although both HO-1 and HO-2 catalyze the identical biochemical reaction, there are some fundamental differences between the two in genetic origin, primary structure, and molecular weight. HO-1, once expressed under various pathological conditions, has an ability to metabolize high amounts free heme to produce high concentrations of its enzymatic by-products that can influence various biological events, and has recently been the focus of considerable medical interest.(3) HO-1 expression can confer cytoprotection and anti-inflammation in gastric and intestinal disease models. The cytoprotective effects of HO-1 are related to end-products formation. The pharmacological application of CO and biliverdin/bilirubin can mimic the HO-1-dependent cytoprotection and anti-inflammation in many injury models. In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview on the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation and function of HO-1 and its possible clinical implications, especially in gastrointestinal diseases.

Regulation of HO-1 Expression

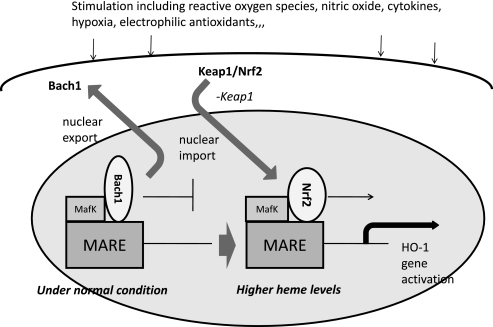

The transcriptional upregulation of the ho-1 gene, and subsequent de novo synthesis of the corresponding protein, occurs in response to elevated levels of its natural substrate heme and to a multiplicity of endogenous factors including NO, cytokines, heavy metals, heat shock, ultraviolet radiation, ischemia-reperfusion, and growth factors.(4,5) Many agents that induce HO-1 are associated with oxidative stress in that they (i) directly or indirectly promote the intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), (ii) fall into a class of electrophilic antioxidant compounds that includes plant-derived polyphenolic substances, or (iii) form complexes with intracellular reduced glutathione and other thiols. Two enhancer regions located at approximately –4 and –10 kb relative to the ho-1 transcriptional start site have been identified in the mouse gene. The dominant sequence element of the enhancers is the stress-responsive elements (StRE), which is structurally and functionally similar to the Maf-response element (MARE) and the antioxidant-response element (ARE).(6) Several transcriptional regulators bind these sequences, including nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) and BTB and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) (Fig. 1). Nrf2 contains a transcription-activation domain and positively regulates HO-1 transcription, whereas Bach1 competes with Nrf2 and represses transcription.(7–9) Under normal conditions, Nrf2 localizes in the cytoplasm, where it interacts with the actin-binding protein, Kelch-like ECH associating protein 1 (Keap1), and is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which results in a lower accumulation of Nrf2 in the nucleus and reduced transcription of the HO-1 gene.(10) Namely, Keap1 acts as negative regulator of Nrf2. Various stimuli, including electrophiles and oxidative stress, liberate Nrf2 from Keap1, allowing Nrf2 to translocate into the nucleus and to bind to stress- or antioxidant-response elements (StRE/ARE). Nuclearly translocated Nrf2 provides immediate transactivation of regulated encoding genes. In this sequence of Nrf2 activation, the phosphorylation of Nrf2 is an important event in the dissociation of Nrf2 from Keap1.(11) Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the oxidation of Keap1 cysteine residues causes a change in the affinity of Keap1 with Nrf2, easily releasing Nrf2.(12,13) Thus the Nrf2-Keap1 system is considered a major defense mechanism that plays a key role in the induction of HO-1.

Fig. 1.

Model describing the regulation of ho-1 or other target genes by Bach1 and heme. Besides MafK, other Maf-related factors may also serve as partners for Bach1. Bach1 occupies MARE enhancers to repress transcription of ho-1 gene under normal conditions. An increase in heme levels alleviates Bach1-mediated repression through inhibition of its DNA-binding activity and subsequent nuclear export, making MAREs available for activating Maf complexes including Nrf2.

Bach1 under baseline condition forms a heterodimer with small maf proteins that represses transcription of the ho-1 gene by binding to MARE in the 5'-untranslated region of the ho-1 promoter. Under conditions of excess heme, increased heme binding to Bach1 causes a conformational change and a decrease in DNA-binding activity followed by nuclear export of Bach1, which in turn leads to transcriptional activation of the ho-1 gene through MARE. Heme also induced nuclear translocation of Nrf2, a partner molecule for the family, and promotes stabilization of Nrf2. Thus, an intracellular heme concentration displaces Bach1 from the MARE sequences by heme binding, which then permits Nrf2 binding to a member of small maf proteins, ultimately resulting in transcriptional activation of ho-1 genes.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated signaling pathway was also recognized as able to mediate the induction of HO-1 by extracellular stimuli. The phosphatidylinositol 3 kianse (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway is also involved in HO-1 regulation.(14) Akt can directly phosphorylate HO-1 protein at Ser-188 and modulate its activity. In addition to the transcriptional regulation, a recent study has shown that HO-1 is subjected to post-translational regulation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system through an ER-associated degradation pathway.(15)

Reaction Products of HO-1 and Their Roles

It is most likely that the many properties including anti-inflammation and cytoprotection afforded by HO-1 may be attributed not only its own action but also to other actions of three by-products of HO-1 activity. Especially in anti-inflammation, the degradation of the pro-oxidant heme by HO-1 itself, the signaling action of CO, the antioxidant properties of biliverdin/bilirubin, and the sequestration of free iron by ferritin could all concertedly contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects observed with HO-1.

Carbon monoxide (CO)

CO is known to be an activator of soluble guanylate cyclase (GC). Though CO is a weak activator of GC in vitro with much lower potency and efficacy than NO, application of CO to a number of different tissues results in increased cGMP production, activation of type I cGMP-dependent protein kinase and smooth muscle relaxation,(1) suggesting that in vivo CO does modulate cGMP levels. The activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I is one of the target of CO that acts as smooth muscle relaxation by direct effects on the contractile machinery as well as by altering Ca2+ homeostasis and voltagegated ion channel activity.(16) CO has also reported to activate K+ channels in a variety of tissues, including gastrointestinal tract. Intracellular cGMP activate K+ channel and cGMP level is increased by the treatment of exogenous CO. The antiapoptotic potential of CO has been reported. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induced apoptosis in mouse fibroblasts(17) and endothelial cells(18) were inhibited by exogenous CO treatment. This anti-apoptotic effect of CO is reported to depend on p38 MAPK pathway(18) and its upstream MAPK kinase (MKK3).(19) On the other hand, in Jurkatt T cells, CO treatment increased Fas/CD95-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, HO-1 or CO cooperated with NF-κB-dependent antiapoptotic genes to protect against TNF-α-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis.(20) Anti-inflammatory effect of CO has been reported using cell culture and animal models of sepsis.(21) In macrophages, CO inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and macrophage inflammatory protein-1, through modulation of p38 MAPK activation.(21) In human T cells, CO suppressed IL-2 secretion and clonal expansion via inhibition of ERK pathway.(22) CO also inhibited the expression of pro-inflammatory enzymes, such as inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and cyclo-xygenase-2, in macrophages via the regulation of C/EBP and NF-κB activation.(23) In human colonic epithelial cells, the inhibitory effects of CO on iNOS expression and IL-6 secretion were dependent on the modulation of NF-κB, activator protein-1 (AP-1), C/EBP activation, and MAPK pathway.(24) Our group has recently shown the beneficial effect of CO to colonic epithelial cell restitution.(25) It has been suggested that submucosal myofibroblast has a crucial role of epithelial cell restitution via TGF-β secretion. In our experiments, CO induces fibroblast growth factor-15 (FGF15) expression in mouse colonic myofibroblast via inhibition of mir710, and FGF15 enhances the restitution of mouse colonic epithelial cells.(25)

Biliverdin/bilirubin

Biliverdin and bilirubin both act as antioxidants in vitro and in vivo(26–28) and their increased local concentrations after HO induction may be beneficial in protecting several types of cells from injury. Bilirubin can scavenge peroxyl radicals in vitro as effectively as α-tocopherol, which is regarded as the most potent antioxidant against lipid peroxidation.(27) Several epidemiological studies indicate that mild to moderately elevated serum bilirubin levels are associated with a better outcome in diseases involving oxidative stress.(29) High plasma bilirubin levels in the general population are correlated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease.(30) Ossola et al.(31,32) demonstrated that the administration of bilirubin completely inhibited HO induction as well as oxidative stress parameters such as glutathione and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances in rat liver exposed to ultraviolet A and copper sulfate. These results suggest that bilirubin is a major contributor to cytoprotective activities against oxidative stress. Otani et al.(33) demonstrated for the first time that oxidative stress in sepsis quickly induced HO-1 in intestinal mucosa and that the bilirubin produced subsequently acted as an antioxidant. They showed that the concentration of bilirubin in the intestinal mucosa increased to slightly more than twice control values at 3 and 5 h after LPS injection, then peaked at 4.3-fold control values at 10 h. Vachharajani et al.(34) demonstrated that biliverdin is as effective as hemin in attenuating LPS-induced expression of endothelial selectins in the small and large intestine, indicating that biliverdin itself or its subsequent metabolite bilirubin may be more important than CO production in mediating the beneficial anti-inflammatory effects of HO-1 in a model of LPS-induced selectin upregulation. Hayashi et al.(35) showed that the effects of HO-1 induction on leukocyte adhesion could be mimicked by bilirubin, suggesting that this product of HO reaction is an important contributor to the anti-inflammatory effects of HO. However, no report has appeared on the measurement of tissue levels of biliverdin/bilirubin in human gastrointestinal tract, and even experimental models have not clarified the role of the biliverdin-bilirubin pathway in gastrointestinal diseases.

Lessons from HO-1, Nrf2, and Bach1-Deficient Mice

In 1999, Yachie et al.(36,37) firstly reported the first case of human HO-1 deficiency. This patient suffered persistent hemolytic anemia and an abnormal coagulation/fibrinolysis system, which were associated with elevated thrombomodulin and von Willebrand factor, indicating persistent endothelial damage. Mice with a HO-1 null mutation have been shown to develop anemia associated with hepatic and renal iron overload(38) and right ventricular infarction after chronic hypoxia exposure.(39) Absence of HO-1 exacerbates ischemia and reperfusion injury,(40,41) atherosclerotic lesion and vascular remoldeling,(42) chronic renovascular hypertension and acute renal failure,(43) and end-organ damage and mortality after lipopolysaccharide injection.(44) These findings provide strong evidence to support that HO-1 has important functions in normal physiology and pathophysiology, especially associated with oxidative stress.

Nrf2 regulates the inducible expression of a group of detoxication enzymes, such as glutathione S-transferase and NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase, via antioxidant response elements. In addition, Ishii et al.(45) have shown that Nrf2 also controls the expression of a group of electrophile- and oxidative stress-inducible proteins and activities, which includes HO-1, A170, and peroxiredoxin using peritoneal macrophages from Nrf2-deficient mice. Nrf2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis.(46) It has been reported that anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties with the HO-1 induction by transforming growth factor-b1 or 15-deoxy-D(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 are clearly cancelled in Nrf2-deficient mice.(47,48)

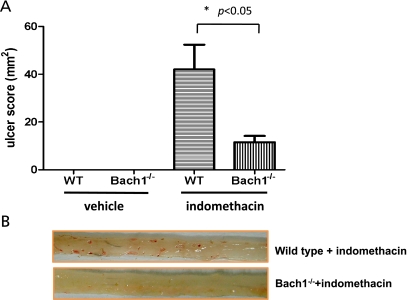

Mice lacking the gene for Bach1 have dramatic increases in HO-1 expression in the heart, lung, liver, and gastro-intestinal tract, indicating a role for Bach1 in tonic suppression of HO-1 transcription. Bach1 deficiency ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatic injury,(49) hyperoxic lung injury,(50) myocardial injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion,(51) hypertensive cardiopathy,(52) spinal cord injury,(53) indomethacin-induced intestinal injury,(54) and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E.(55) Recently, we have investigated the role of Bach1 in the pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced intestinal injury using Bach1-deficient mice, which are kindly presented from Prof. Igarashi (Tohoku University, Japan).(56) We have shown that the indomethacin-induced intestinal injury is remarkably improved in Bach1-deficient mice (Fig. 2), and that the increased expression of inflammatory chemokines and myeloperoxidase activity in the intestinal mucosa is suppressed in Bach1-deficient mice, respectively.(54) In addition, these beneficial effects observed in Bach1-deficient mice are reversed by the cotreatment with an HO-1 inhibitor, SnPP, indicating that these effects are mediated by the HO-1 activity.

Fig. 2.

(A) Effect of Bach1 deficiency on ulcer index in the intestinal mucosa treated with indomethacin. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of five to seven mice. (B) Macroscopic findings of the small intestine in mice treated with indomethacin. The administration of indomethacin provoked multiple erosions in the small intestine in wild type mice. On the other hand, in Bach1-deficient mice, the number and the severity of legions were clearly diminished.

HO-1 Expression in Gastrointestinal Tract

We have investigated the expression of ho-1 mRNA and HO-1 protein in colon specimens obtained from patients with ulcerative colitis.(57) The expression of ho-1 mRNA in inflamed colonic mucosa is remarkably increased compared with normal controls. Furthermore, in the inflamed mucosa of active ulcerative colitis, HO-1 protein expression was also increased. These results suggest that the increased expression of HO-1 protein is mainly derived from the increase in transcription of ho-1 in the inflamed intestine. In the histological study, we have confirmed the expression of HO-1 in inflamed intestinal mucosa and that it was localized in the inflammatory cells, mainly mononuclear cells in the colonic submucosal layer, but not in epithelial cells. Some of the HO-1 positively stained cells were positively stained CD68 cells. Maestrelli et al.(58) have reported that the majority of HO-1-positive cells in the alveolar spaces were CD68-positive cells, and Yoshiki et al.(59) have reported that HO-1 expression localized in CD68-positive macrophages. Thus, the expression of HO-1 has been observed mainly in macrophages in various organs. However, other reports regarding the localization of HO-1 in human colonic mucosa have described HO-1 expression not only in inflammatory cells but also in the epithelial cells.(60,61)

Recent studies showed that glutamine, the major fuel for enterocytes, induces HO-1 in intestinal mucosa of rats(62) as well as humans.(63) Substantial expression of HO-1 after glutamine administration is observed in villous epithelial cells, crypts and muscular layers. In rats, the protective effect of glutamine on the intestine is associated with HO-1 induction in a model of ischemia-reperfusion injury.(62) In human duodenal mucosa, HO-1 is constitutively expressed in nearly all types of intestinal epithelial cells and approximately 10% of lamina propria cells from the villi core, whereas its expression is minimal in deep mucosa. Glutamine increases intestinal HO-1 expression in both intestinal epithelial cells and lamina propria cells, and this histological finding is correlated with an increase in mRNA levels for HO-1. These data suggest that the modulation of HO-1 expression by glutamine may contribute to its protective effect on intestinal injury, together with the previously reported reduction of proinflammatory cytokines production.(64) Further investigation is required as to whether glutamine may affect HO-1 expression under conditions of intestinal inflammation, including inflammatory bowel disease. As one example, HO-1 mRNA expression was reported to be not affected in pouchitis.(65)

Roles of HO-1 in Gastric Diseases

It has been demonstrated that gastric cytoprotection induced by polaprezinc,(66) eupatilin,(67) and ketamine(68) against noxious agents is mediated by HO-1 induction (Table 1). Recent our study shows that lansoprazole, a gastric H+/K+ ATPase inhibitor, up-regulates HO-1 expression in rat gastric epithelial cells, and the up-regulated HO-1 has anti-inflammatory effects, and that lansoprazole-induced HO-1 induction is mediated by the activation, phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Nrf2 in accompaniment with the dissection of oxidized Keap1.(69,70) In this study, we firstly demonstrated that oxidation of Keap1 protein is crucial in the induction of HO-1 by lansoprazole.

Table 1.

Induction of heme oxygenase-1 inhibits gastrointestinal diseases

| Type of experimental models | HO-1 induction | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | |||

| gastroparesis in diabetic mice | CD206(+)/HO1(+) M2 macrophage | protection for Kit cells | Choi et al. 2010 |

| HCl-induced acute gastric mucosal lesions | polaprezinc | cytoprotection | Ueda et al. 2009 |

| gastric mucosal cells | lansoprazole | anti-inflammatory | Takagi et al. 2009 |

| endothelial cells/macrophages | lansoprazole | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dependecnt cytoprotection | Schulz-Geske et al. 2009 |

| diabetic gastroparesis | hemin | protection for Cajal cells | Choi et al. 2008 |

| H2O2-induced cell injury | eupatilin | cytoprotection | Choi et al. 2008 |

| LPS-induced gastricl injury | ketamine | NF-kappaB ↓, AP-1 ↓, iNOS ↓ | Helmer et al. 2006 |

| gastric smooth muscle excitability | CoCl2 | CO-dependent | Kadinov et al. 2002 |

| Small intestine | |||

| Ischemia-reperfusion | ischemic preconditioning | Mallick et al. 2010 | |

| indomethacin-induced intestinal injury | Bach1−/− | inflammatory chemokine ↓, MPO ↓ | Harusato et al. 2009 |

| indomethacin-induced cell injury | sulforaphane | cytoprotection | Yen et al. 2009 |

| indomethacin-induced intestinal injury | lansoprazole | cytoprotection | Higuchi et al. 2009 |

| hemorrhagic shock-induced intestinal injury | glutamine | anti-inflammatory, cytoprotection | Umeda et al. 2009 |

| postoperative ileus | CORM | p38-dependent pathway ↑, ERK1/2 ↓ | De Backer et al. 2009 |

| hemorrhagic shock-induced gastric mucosal injury | HO1-secreting Lactococcus lactis | anti-inflammatory, cytoprotection | Pang et al. 2009 |

| feline ileal smooth muscle cells | eupatilin | ERK and Nrf2 signaling | Song et al. 2008 |

| lipopolysaccharide-induced intestinal injury | HO1-secreting Lactococcus lactis | anti-inflammatory, intestinal barrier ↑ | Pang et al. 2008 |

| neutrophil-mediated intestinal damage | cobalt protoporphyrin IX chloride | neutrophil O2- production ↓ | Li et al. 2008 |

| trauma-hemorrhage-induced intestinal injury | estrogen | p38 MAPK-dependent pathway | Hsu et al. 2008 |

| sepsis | HO-1 Tg mice | CO-dpendent host defense response ↑ | Chung et al. 2008 |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | Cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP) | cytoprotection | Wasserberg et al. 2007 |

| LPS-induced intestinal injury | Intestinal preconditioning | bilirubin-dependent cytoprotection | Tamion et al. 2007 |

| burn injury-induced impaired intestinal transit | hemin | iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β ↓ | Gan et al. 2007 |

| endotoxin-shock model | hemin | anti-inflammatory | Tamion et al. 2006 |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate | leucocyte-endothelial interactions ↓ | Mallick et al. 2006 |

| radiation-induced intestinal damage | glutamate | NF-kappaB ↓ | Giris et al. 2006 |

| radiation-induced intestinal damage | octreotide | anti-inflammatory | Abbasoglu et al. 2006 |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | hypothermia | cytoprotection | Sakamoto et al. 2005 |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | hemin | MPO ↓ | Attuwaybi et al. 2004 |

| impaired intestinal transit after gut I/R | Hypertonic saline | anti-inflammatory | Attuwaybi et al. 2004 |

| hemin | intestinal cell cycle progression | Uc et al. 2003 | |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | hypothermia | cytoprotection | Attuwaybi et al. 2003 |

| ischemia-reperfusion injury | preconditioning | cytoprotection | Tamion et al. 2002 |

| Large intestine | |||

| DSS-induced colitis | hemin (i.p.) | Treg ↑, IL-17 ↓, apoptosis ↓ | Zhong et al. 2010 |

| DSS-induced colitis | tranilast (enema) | IFN-g ↓, IL-6 ↓ | Sun et al. 2010 |

| colitis-related colon carcinogenesis | 4'-geranyloxy-ferulic acid | modulating proliferation, oxidative stress ↓ | Miyamoto et al. 2008 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | heme, cadmium chloride | damage ↓, MPO ↓ | Varga et al. 2007 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | 2',4',6'-Tris(methoxymethoxy) chalcone | nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB ↓ | Lee et al. 2007 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | glutamine | antioxidant, antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory | Giris et al. 2007 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | octreotide | NF-kappaB ↓ | Erbil et al. 2007 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | gliotoxin | NF-kappaB ↓ | Jun et al. 2006 |

| DSS-induced colitis | cobalt-protoporphyrin | biliverdin-dependent | Berberat et al. 2005 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | CO | anti-inflammatory | Hegazi et al. 2005 |

| TNBS-induced colitis | bolinaquinone (BQ) petrosaspongiolide M (PT) | NF-kappaB ↓ | Busserolles et al. 2005 |

In addition to cytoprotection by HO-1, it has been shown that HO-1 exerts a modulatory role on gastric smooth muscle excitability via CO production.(71,72) Using a diabetic gastroparesis model, Choi et al.(72,73) have demonstrated that Kit expression in interstitial cells of Cajal is lost during diabetic gastroparesis due to increased levels of oxidative stress caused by low levels of HO-1, and that CD206(+) M2 macrophages that express HO1 appear to be required for prevention of diabetes-induced delayed gastric emptying. Because lansoprazole induces HO-1 in macrophages,(74) it should be investigated whether lansoprazole could reverse delayed gastric emptying in diabetic mice via the induction of HO-1.

Roles of HO-1 in Small Intestinal Diseases

Three reports are available on the use of HO-1 inducers (lansoprazole, sulforafane, and Bach1-deficiency) in indomethacin-induced gastric mucosal injury(54,75,76) (Table 1). Higuchi et al.(75) have shown that lansoprazole inhibits indomethacin-induced intestinal injury in rats and that the inhibition is reversed by SnPP, an HO-1 inhibitor. Because CORM, a CO donor, also ameliorates these injury, cytoprotective effects of HO-1, in part, exerts via CO-dependent manner. Many reports have confirmed the anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects of HO-1 inducers on small intestinal injuries induced by ischemia-reperfusion,(77–83) lipopolysaccharide,(84–86) radiation,(87–89) and burn shock.(90–93) Pang et al.(86,94) have used live Lactococcus lactis secreting bioactive HO-1 to treat intestinal mucosal injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in rats. Intragastric administration of HO-1-secreting Lactococcus lactis strain led to bioactive delivery of HO-1 at intestinal mucosa and significantly decreased mucosal damage, myeloperoxidase activity, bacterial translocation, and tumor necrosis factor-α levels when compared with rats treated with the wild-type strain.

Among products of HO-1, CO may be an important mediator of the host defense response to sepsis.(95) Chung et al.(95) have demonstrated that targeting HO-1 to smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts of blood vessels and bowel ameliorates sepsis-induced death associated with Enterococcus faecalis in association with enhancement of bacterial clearance by increasing phagocytosis and the endogenous antimicrobial response, and that injection of a CO-releasing molecule into wild type mice increases phagocytosis and rescues HO-1-deficient mice from sepsis-induced lethality. More interstingly, it has been reported that CO-releasing molecule ameliorates postoperative ileus and muscularis inflammation, and that these protective effects are, at least in part, mediated through induction of HO-1, in a p38-dependent manner, as well as reduction of ERK1/2 activation. These findings shown here may be of significant importance in clinical small bowel transplantation, post-operative condition for small intestine, or sepsis-related intestinal failure.

Role of HO-1 in Large Intestinal Diseases

Wang et al.(96) used a rat model of inflammatory bowel disease induced by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) to investigate whether the expression of HO-1 is an endogenous mechanism responsible for host defense against inflammatory injury in colonic tissue. They demonstrated that HO activity and HO-1 gene expression increased markedly after TNBS induction, and that administration of tin mesoporphyrin (SnMP), an HO inhibitor, potentiated the colonic damage as well as decreased HO-1 activity. These results indicate that HO-1 plays a protective role in the colonic damage induced by TNBS enema. Using a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis model of mice, we have demonstrated that HO-1 mRNA is markedly induced in inflamed colonic tissue, whereas HO-2 mRNA is constitutively expressed.(97) Co-administration with ZnPP, an HO inhibitor, also enhanced intestinal inflammation and increased the disease activity index as determined by a calculated score based on changes in body weight, stool consistency, and intestinal bleeding.

Recent investigation has shown that upregulation of HO-1 by several HO-1 inducers significantly reduces the intestinal injuries induced by DSS(98–100) or TNBS(101–107) (Table 1). In these studies, HO-1 inducers increase HO-1 expression in intestinal mucosa, and ameliorate mucosal injury as well as inflammatory cell accumulation by decreasing infiltrating neutrophils and lymphocytes via the inhibition of NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory cytokines. To further assess the anti-inflammatory mechanisms, Zhong et al.(100) have examined whether hemin enhanced the proliferation of Treg cells and suppressed the production of interleukin (IL)-17 in a DSS-colitis model. Flow cytometry analysis has revealed that hemin markedly expands the CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg population and attenuates IL-17 and TH17-related cytokines. It has been also demonstrated that HO-1 exerts immunoregulatory effects by modulating Treg cell function,(108) and that HO-1 activity in antigen-presenting cells is important for Treg-mediated suppression, providing an explanation for the apparent defect in immune regulation in HO-1-deficient mice.(109)

Conclusion

The biological significance of HO-1 up-regulation in gastro-intestinal inflammation remains to be fully elucidated. However, there is no doubt that CO derived from HO-1 exerts significant effects on many pathways of cellular metabolism. In inflamed intestinal cells CO may inhibit the inflammatory response, by consequently influencing the synthesis of cytokines, expression of adhesion molecules, and cell proliferation. Although the mechanisms underlying HO-1 activity on gene expression are not well known, the results obtained in recent years have demonstrated its importance in modulation of the inflammatory reaction. Recent experimental studies clearly demonstrated that HO-1 expression is a self-defense mechanism against inflammation. These data suggest that HO-1 is a possible therapeutic target in several kinds of gastrointestinal diseases.

References

- 1.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibahara S. Regulation of heme oxygenase gene expression. Semin Hematol. 1988;25:370–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryter SW, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from metabolism to molecular therapy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:251–260. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0170TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi T, Shimizu H, Morimatsu H, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 is an essential cytoprotective component in oxidative tissue injury induced by hemorrhagic shock. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;44:28–40. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.08-210-HO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:166–174. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igarashi K, Sun J. The heme-Bach1 pathway in the regulation of oxidative stress response and erythroid differentiation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:107–118. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morse D, Lin L, Choi AM, Ryter SW. Heme oxygenase-1, a critical arbitrator of cell death pathways in lung injury and disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Jang, Piao S, Cha YN, Kim C. Taurine chloramine activates Nrf2, increases HO-1 expression and protects cells from death caused by hydrogen peroxide. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;45:37–43. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.08-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho HY, Reddy SP, Kleeberger SR. Nrf2 defends the lung from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:76–87. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloom DA, Jaiswal AK. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 at Ser40 by protein kinase C in response to antioxidants leads to the release of Nrf2 from INrf2, but is not required for Nrf2 stabilization/accumulation in the nucleus and transcriptional activation of antioxidant response element-mediated NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44675–44682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Cole RN, et al. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11908–11913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, et al. Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 in determining Nrf2 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2758–2770. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01704-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salinas M, Wang J, Rosa de Sagarra M, et al. Protein kinase Akt/PKB phosphorylates heme oxygenase-1 in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin PH, Chiang MT, Chau LY. Ubiquitin-proteasome system mediates heme oxygenase-1 degradation through endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1826–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carvajal JA, Germain AM, Huidobro-Toro JP, Weiner CP. Molecular mechanism of cGMP-mediated smooth muscle relaxation. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:409–420. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200009)184:3<409::AID-JCP16>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrache I, Otterbein LE, Alam J, Wiegand GW, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in cultured fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L312–L319. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.2.L312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brouard S, Otterbein LE, Anrather J, et al. Carbon monoxide generated by heme oxygenase 1 suppresses endothelial cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1015–1026. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Shan P, Otterbein LE, et al. Carbon monoxide inhibition of apoptosis during ischemia-reperfusion lung injury is dependent on the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and involves caspase 3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1248–1258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208419200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brouard S, Berberat PO, Tobiasch E, Seldon MP, Bach FH, Soares MP. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide requires the activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B to protect endothelial cells from tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17950–17961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, et al. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:422–428. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pae HO, Oh GS, Choi BM, et al. Carbon monoxide produced by heme oxygenase-1 suppresses T cell proliferation via inhibition of IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2004;172:4744–4751. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suh GY, Jin Y, Yi AK, Wang XM, Choi AM. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein mediates carbon monoxide-induced suppression of cyclooxygenase-2. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:220–226. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0154OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Megias J, Busserolles J, Alcaraz MJ. The carbon monoxide-releasing molecule CORM-2 inhibits the inflammatory response induced by cytokines in Caco-2 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:977–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchiyama K, Naito Y, Takagi T, et al. Carbon monoxide enhance colonic epithelial restitution via FGF15 derived from colonic myofibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1122–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocker R, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Antioxidant activity of albumin-bound bilirubin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5918–5922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987;235:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Llesuy SF, Tomaro ML. Heme oxygenase and oxidative stress. Evidence of involvement of bilirubin as physiological protector against oxidative damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1223:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedlak TW, Snyder SH. Bilirubin benefits: cellular protection by a biliverdin reductase antioxidant cycle. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1776–1782. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Djoussé L, Rothman KJ, Cupples LA, Levy D, Ellison RC. Effect of serum albumin and bilirubin on the risk of myocardial infarction (the Framingham Offspring Study) Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:485–488. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ossola JO, Groppa MD, Tomaro ML. Relationship between oxidative stress and heme oxygenase induction by copper sulfate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;337:332–337. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ossola JO, Tomaro ML. Heme oxygenase induction by UVA radiation. A response to oxidative stress in rat liver. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otani K, Shimizu S, Chijiiwa K, et al. Administration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide to rats induces heme oxygenase-1 and formation of antioxidant bilirubin in the intestinal mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2313–2319. doi: 10.1023/a:1005626622203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vachharajani TJ, Work J, Issekutz AC, Granger DN. Heme oxygenase modulates selectin expression in different regional vascular beds. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1613–H1617. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.5.H1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi S, Takamiya R, Yamaguchi T, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 suppresses venular leukocyte adhesion elicited by oxidative stress: role of bilirubin generated by the enzyme. Circ Res. 1999;85:663–671. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yachie A, Niida Y, Wada T, et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:129–135. doi: 10.1172/JCI4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawashima A, Oda Y, Yachie A, Koizumi S, Nakanishi I. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency: the first autopsy case. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:125–130. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.30217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poss KD, Tonegawa S. Heme oxygenase 1 is required for mammalian iron reutilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10919–10924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yet SF, Perrella MA, Layne MD, et al. Hypoxia induces severe right ventricular dilatation and infarction in heme oxygenase-1 null mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:R23–R29. doi: 10.1172/JCI6163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida T, Maulik N, Ho YS, Alam J, Das DK. H(mox-1) constitutes an adaptive response to effect antioxidant cardioprotection: a study with transgenic mice heterozygous for targeted disruption of the Heme oxygenase-1 gene. Circulation. 2001;103:1695–1701. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.12.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Wei J, Peng DH, Layne MD, Yet SF. Absence of heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2005;54:778–784. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yet SF, Layne MD, Liu X, et al. Absence of heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates atherosclerotic lesion formation and vascular remodeling. FASEB J. 2003;17:1759–1761. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0187fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiesel P, Patel AP, Carvajal IM, et al. Exacerbation of chronic renovascular hypertension and acute renal failure in heme oxygenase-1-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2001;88:1088–1094. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.091521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiesel P, Patel AP, DiFonzo N, et al. Endotoxin-induced mortality is related to increased oxidative stress and end-organ dysfunction, not refractory hypotension, in heme oxygenase-1-deficient mice. Circulation. 2000;102:3015–3022. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.24.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishii T, Itoh K, Takahashi S, et al. Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16023–16029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khor TO, Huang MT, Kwon KH, Chan JY, Reddy BS, Kong AN. Nrf2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11580–11584. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Churchman AT, Anwar AA, Li FY, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 elicits Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses in aortic smooth muscle cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2282–2292. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Itoh K, Mochizuki M, Ishii Y, et al. Transcription factor Nrf2 regulates inflammation by mediating the effect of 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin j(2) Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:36–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.36-45.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iida A, Inagaki K, Miyazaki A, Yonemori F, Ito E, Igarashi K. Bach1 deficiency ameliorates hepatic injury in a mouse model. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;217:223–229. doi: 10.1620/tjem.217.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanimoto T, Hattori N, Senoo T, et al. Genetic ablation of the Bach1 gene reduces hyperoxic lung injury in mice: role of IL-6. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yano Y, Ozono R, Oishi Y, et al. Genetic ablation of the transcription repressor Bach1 leads to myocardial protection against ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Genes Cells. 2006;11:791–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mito S, Ozono R, Oshima T, et al. Myocardial protection against pressure overload in mice lacking Bach1, a transcriptional repressor of heme oxygenase-1. Hypertension. 2008;51:1570–1577. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanno H, Ozawa H, Dohi Y, Sekiguchi A, Igarashi K, Itoi E. Genetic ablation of transcription repressor Bach1 reduces neural tissue damage and improves locomotor function after spinal cord injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:31–39. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harusato A, Naito Y, Takagi T, et al. Inhibition of Bach1 ameliorates indomethacin-induced intestinal injury in mice. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 7):149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watari Y, Yamamoto Y, Brydun A, et al. Ablation of the Bach1 gene leads to the suppression of atherosclerosis in Bach1 and apolipoprotein E double knockout mice. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:783–792. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun J, Hoshino H, Takaku K, et al. Hemoprotein Bach1 regulates enhancer availability of heme oxygenase-1 gene. EMBO J. 2002;21:5216–5224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takagi T, Naito Y, Mizushima K, et al. Increased intestinal expression of heme oxygenase-1 and its localization in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 2):S229–S233. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maestrelli P, El Messlemani AH, De Fina O, et al. Increased expression of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 in alveolar spaces and HO-2 in alveolar walls of smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1508–1513. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2011083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshiki N, Kubota T, Aso T. Identification of heme oxygenase in human endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5033–5038. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paul G, Bataille F, Obermeier F, et al. Analysis of intestinal haem-oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in clinical and experimental colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barton SG, Rampton DS, Winrow VR, Domizio P, Feakins RM. Expression of heat shock protein 32 (hemoxygenase-1) in the normal and inflamed human stomach and colon: an immunohistochemical study. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:329–334. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0329:eohsph>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tamaki T, Konoeda Y, Yasuhara M, et al. Glutamine-induced heme oxygenase-1 protects intestines and hearts from warm ischemic injury. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1018–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coëffier M, Le Pessot F, Leplingard A, et al. Acute enteral glutamine infusion enhances heme oxygenase-1 expression in human duodenal mucosa. J Nutr. 2002;132:2570–2573. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ameho CK, Adjei AA, Harrison EK, et al. Prophylactic effect of dietary glutamine supplementation on interleukin 8 and tumour necrosis factor alpha production in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid induced colitis. Gut. 1997;41:487–493. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leplingard A, Brung-Lefebvre M, Guédon C, et al. Increase in cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide-synthase-2 mRNAs in pouchitis without modification of inducible isoenzyme heme-oxygenase-1. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2129–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ueda K, Ueyama T, Oka M, Ito T, Tsuruo Y, Ichinose M. Polaprezinc (Zinc L-carnosine) is a potent inducer of anti-oxidative stress enzyme, heme oxygenase (HO)-1—a new mechanism of gastric mucosal protection. Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:285–294. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09056fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choi EJ, Oh HM, Na BR, et al. Eupatilin protects gastric epithelial cells from oxidative damage and down-regulates genes responsible for the cellular oxidative stress. Pharma Res. 2008;25:1355–1364. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helmer KS, Suliburk JW, Mercer DW. Ketamine-induced gastroprotection during endotoxemia: role of heme-oxygenase-1. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1571–1581. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-9013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takagi T, Naito Y, Okada H, et al. Lansoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, mediates anti-inflammatory effect in gastric mucosal cells through the induction of heme oxygenase-1 via activation of NF-E2-related factor 2 and oxidation of kelch-like ECH-associating protein 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:255–264. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takagi T, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. The expression of heme oxygenase-1 induced by lansoprazole. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;45:9–13. doi: 10.3164/jcbnSR09-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kadinov B, Itzev D, Gagov H, Christova T, Bolton TB, Duridanova D. Induction of heme oxygenase in guinea-pig stomach: roles in contraction and in single muscle cell ionic currents. Acta Physiol Scand. 2002;175:297–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2002.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi KM, Gibbons SJ, Nguyen TV, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 protects interstitial cells of Cajal from oxidative stress and reverses diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2055–2064. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi KM, Kashyap PC, Dutta N, et al. CD206-positive M2 macrophages that express heme oxygenase-1 protect against diabetic gastroparesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.014. Feb 20. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schulz-Geske S, Erdmann K, Wong RJ, Stevenson DK, Schroder H, Grosser N. Molecular mechanism and functional consequences of lansoprazole-mediated heme oxygenase-1 induction. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4392–4401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Higuchi K, Yoda Y, Amagase K, et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced small intestinal mucosal injury: prophylactic potential of lansoprazole. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;45:125–130. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.SR09-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yeh CT, Chiu HF, Yen GC. Protective effect of sulforaphane on indomethacin-induced cytotoxicity via heme oxygenase-1 expression in human intestinal Int 407 cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:1166–1176. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tamion F, Richard V, Lacoume Y, Thuillez C. Intestinal preconditioning prevents systemic inflammatory response in hemorrhagic shock. Role of HO-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G408–414. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Attuwaybi BO, Hassoun HT, Zou L, et al. Hypothermia protects against gut ischemia/reperfusion-induced impaired intestinal transit by inducing heme oxygenase-1. J Surg Res. 2003;115:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Attuwaybi BO, Kozar RA, Moore-Olufemi SD, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 induction by hemin protects against gut ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2004;118:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Attuwaybi B, Kozar RA, Gates KS, et al. Hypertonic saline prevents inflammation, injury, and impaired intestinal transit after gut ischemia/reperfusion by inducing heme oxygenase 1 enzyme. J Trauma. 2004;56:749–758. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000119686.33487.65. discussion 758–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakamoto N, Kokura S, Okuda T, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 (Hsp32) is involved in the protection of small intestine by whole body mild hyperthermia from ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat. Int J Hyperthermia. 2005;21:603–614. doi: 10.1080/02656730500188599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wasserberg N, Pileggi A, Salgar SK, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 upregulation protects against intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury: a laboratory based study. Int J Surg (London, England) 2007;5:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mallick IH, Winslet MC, Seifalian AM. Ischemic preconditioning of small bowel mitigates the late phase of reperfusion injury: heme oxygenase mediates cytoprotection. Am J Surg. 2010;199:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tamion F, Richard V, Renet S, Thuillez C. Protective effects of heme-oxygenase expression against endotoxic shock: inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and augmentation of interleukin-10. J Trauma. 2006;61:1078–1084. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000239359.41464.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tamion F, Richard V, Renet S, Thuillez C. Intestinal preconditioning prevents inflammatory response by modulating heme oxygenase-1 expression in endotoxic shock model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1308–G1314. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00154.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pang QF, Ji Y, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Zhou QM, Hu G, Zeng Y. Protective effects of a heme oxygenase-1-secreting Lactococcus lactis on mucosal injury induced by hemorrhagic shock in rats. J Surg Res. 2009;153:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abbasoǧlu SD, Erbil Y, Eren T, et al. The effect of heme oxygenase-1 induction by octreotide on radiation enteritis. Peptides. 2006;27:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Giriş M, Erbil Y, Oztezcan S, et al. The effect of heme oxygenase-1 induction by glutamine on radiation-induced intestinal damage: the effect of heme oxygenase-1 on radiation enteritis. Am J Surg. 2006;191:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mallick IH, Winslet MC, Seifalian AM. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate protects the small bowel from warm ischaemia/reperfusion injury of the intestine: the role of haem oxygenase. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;111:373–380. doi: 10.1042/CS20060119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gan HT, Chen JD. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 improves impaired intestinal transit after burn injury. Surgery. 2007;141:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsu JT, Kan WH, Hsieh CH, et al. Mechanism of estrogen-mediated intestinal protection following trauma-hemorrhage: p38 MAPK-dependent upregulation of HO-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1825–R1831. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00112.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. Heme oxygenase-1 protects against neutrophil-mediated intestinal damage by down-regulation of neutrophil p47phox and p67phox activity and O2- production in a two-hit model of alcohol intoxication and burn injury. J Immunol. 2008;180:6933–6940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Umeda K, Takahashi T, Inoue K, et al. Prevention of hemorrhagic shock-induced intestinal tissue injury by glutamine via heme oxygenase-1 induction. Shock. 2009;31:40–49. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318177823a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pang Q, Ji Y, Li Y, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Hu G, Zeng Y. Intragastric administration with recombinant Lactococcus lactis producing heme oxygenase-1 prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia in rats. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;283:62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chung SW, Liu X, Macias AA, Baron RM, Perrella MA. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide enhances the host defense response to microbial sepsis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:239–247. doi: 10.1172/JCI32730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang WP, Guo X, Koo MW, et al. Protective role of heme oxygenase-1 on trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G586–G594. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.2.G586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Naito Y, Takagi T, Yoshikawa T. Heme oxygenase-1: a new therapeutic target for inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Berberat PO, YI AR, Yamashita K, et al. Heme oxygenase-1-generated biliverdin ameliorates experimental murine colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:350–359. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000164017.06538.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sun X, Suzuki K, Nagata M, et al. Rectal administration of tranilast ameliorated acute colitis in mice through increased expression of heme oxygenase-1. Pathol Int. 2010;60:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhong W, Xia Z, Hinrichs D, et al. Hemin exerts multiple protective mechanisms and attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:132–139. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181c61591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Busserolles J, Payá M, D’Auria MV, Gomez-Paloma L, Alcaraz MJ. Protection against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid-induced colonic inflammation in mice by the marine products bolinaquinone and petrosaspongiolide M. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hegazi RA, Rao KN, Mayle A, Sepulveda AR, Otterbein LE, Plevy SE. Carbon monoxide ameliorates chronic murine colitis through a heme oxygenase 1-dependent pathway. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1703–1713. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jun CD, Kim Y, Choi EY, et al. Gliotoxin reduces the severity of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in mice: evidence of the connection between heme oxygenase-1 and the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in vitro and in vivo. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:619–629. doi: 10.1097/01.ibd.0000225340.99108.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Erbil Y, Giriş M, Abbasoǧlu SD, et al. Effect of heme oxygenase-1 induction by octreotide on TNBS-induced colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1852–1858. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giriş M, Erbil Y, Doǧru-Abbasoǧlu S, et al. The effect of heme oxygenase-1 induction by glutamine on TNBS-induced colitis. The effect of glutamine on TNBS colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:591–599. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee SH, Sohn DH, Jin XY, Kim SW, Choi SC, Seo GS. 2',4',6'-tris(methoxymethoxy) chalcone protects against trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis and blocks tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced intestinal epithelial inflammation via heme oxygenase 1-dependent and independent pathways. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Varga C, Laszlo F, Fritz P, et al. Modulation by heme and zinc protoporphyrin of colonic heme oxygenase-1 and experimental inflammatory bowel disease in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;561:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brusko TM, Wasserfall CH, Agarwal A, Kapturczak MH, Atkinson MA. An integral role for heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in maintaining peripheral tolerance by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:5181–5186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.George JF, Braun A, Brusko TM, et al. Suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is dependent on expression of heme oxygenase-1 in antigen-presenting cells. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:154–160. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]