Abstract

Coronary artery disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western world. Acute myocardial infarction, resulting from coronary artery atherosclerosis, is a serious and often fatal consequence of coronary artery disease, resulting in cell death in the myocardium. Pre- and post-conditioning of the myocardium are two treatment strategies that reduce the amount of cell death significantly. Hydrogen sulfide has recently been identified as a potent cardioprotective signaling molecule, which is a highly effective pre- and post-conditioning agent. The cardioprotective signaling pathways involved in hydrogen sulfide-based pre- and post-conditioning will be explored in this article.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, apoptosis, ischemia/reperfusion injury, myocardial protection, oxidative stress

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a serious and often fatal consequence of coronary artery disease. With AMI, the best course of action to limit myocardial infarct size is a timely restoration of blood flow to the ischemic myocardium by either thrombolysis or percutaneous angioplasty [1,2]. Unfortunately, the blockage is rarely recanalized before a considerable amount of damage is done to the myocardium, subsequently leading to persistent heart failure in a large percentage of patients [1,2].

Pre- and post-conditioning and pharmacological treatments to mimic these interventions have been shown to be effective in limiting infarct size in the setting of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) injury in both animals and humans [3]. When coupled with timely reperfusion, pre- and post-conditioning attenuate myocardial infarct size and postischemic left ventricular dysfunction more than reperfusion alone [3]. Both pre- and post-conditioning can be achieved in numerous ways to induce physiological changes that result in increased cytoprotection after reperfusion of the ischemic heart [3].

This article focuses on the novel signaling molecule hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as a pre- and post-conditioning agent to limit infarct size following AMI. H2S exhibits many cytoprotective effects. This article will discuss the use of H2S prior to ischemia to precondition and protect the myocardium during AMI, as well as H2S therapy following the reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium to postcondition and protect the heart against reperfusion injury.

Preconditioning

Myocardial preconditioning is a phenomenon by which the myocardium is protected from ischemia/reperfusion damage by physiological or pharmacological means prior to an ischemic event (i.e., coronary artery occlusion). Therefore, when reperfusion is attained, the myocardium has a greater capacity to resist oxidative and myocardial cell death signals that result from the rapid reintroduction of oxygen to the ischemic tissue. The efficacy of the conferred protection is typically measured by a reduction in myocardial infarct size, as well as a minimized decline in myocardial contractile function.

Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) was first discovered over 20 years ago by Murry et al. [4]. In this seminal study, four rounds of 5 min of nonlethal coronary artery occlusion followed by 5 min of reperfusion was administered prior to the prolonged ischemic bout [4]. They found that these brief periods of ischemia significantly delayed myocardial cell death during a 40-min coronary artery ischemia, thereby demonstrating that they “could exploit ischemia to protect the heart from ischemia” [4]. Since the publication of this seminal work, a considerable amount of research has been published exploring the mechanisms behind IPC and the implementation of pharmacological strategies.

Ischemic preconditioning has been shown to protect the heart across all animal species investigated and is considered to be the most protective intervention against MI/R injury to date [5,6]. Some of the key signaling pathways and mediators involved in IPC are: PI3K, Akt, nitric oxide (NO), PKG, mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP), adenosine, oxygen-derived free radicals and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) [7]. Additionally, adenosine, bradykinin and opioids, which are all released during IPC, also serve to protect the myocardium when pharmacologically administered before an ischemic event [8–10]. Pharmacological preconditioning is distinct from IPC, as no ischemia is induced to obtain the cardioprotective benefits; rather, administration of cardioprotective agents mimic the signaling induced by IPC using exogenous pharmacological application.

Ischemic preconditioning also exhibits two phases of cardioprotection: an early phase, 1–3 h after preconditioning [4], and a late phase, 18–24 h later, which can persist for up to 72 h [11]. The major distinction between these two phases is that the early phase triggers the modification of existing proteins in the myocardium, while the late phase triggers the induction of numerous cytoprotective proteins [5]. Additionally, while early-phase IPC protects against myocardial infarction, it fails to limit myocardial contractile dysfunction or stunning, while late-phase IPC protects against myocardial infarction and preserves left ventricular function [5]. Therefore, late-phase IPC is considered to be more clinically beneficial, as it confers greater cardioprotection and has a longer duration of protective effects [3].

Postconditioning

Myocardial postconditioning is a phenomenon whereby the myocardium is protected from ischemia/reperfusion damage by physiological or pharmacological interventions following ischemia at the time of reperfusion. Postconditioning, similar to pre-conditioning, was first reported using a modulation of ischemia to protect against ischemia. In 1992, Zhao and colleagues conducted unpublished studies on postconditioning in the Vinten–Johansen laboratory in an anesthetized rabbit model of coronary artery occlusion–reperfusion, using 5 min perfusion–ischemia intervals repeated at the onset of reperfusion [3]. These studies were halted owing to a lack of efficacy of the postconditioning treatment, which paralleled treatment performed in preconditioning [3]. Later, a report in 1996 by Na et al. showed that transient ischemia at the onset of arrhythmias during reperfusion suppressed the incidence of ventricular fibrillation in anesthetized cats, and used the term ‘postconditioning’ to describe this phenomenon [12]. Then, again in 2001, the Vinten–Johansen laboratory resumed postconditioning studies, using compressed 30-s cycles to account for the rapid time course of reperfusion injury [3]. Following this, in 2003, Zhao et al. reported that postconditioning, by cycling reperfusion for three 30-s intervals before prolonged reperfusion, significantly reduced infarct size in a dog model of coronary artery occlusion [13].

Ischemic postconditioning (mechanical manipulation of reperfusion blood flow) was initially performed by sequentially releasing and reapplying an external ligature around the coronary artery [13,14]. More recent studies have used fluoroscopically guided angioplasty balloon catheters to administer the sequential reperfusion in a closed-chest model [15], while cell culture models have been used to simulate the intervals of ischemia and reperfusion induced by mechanical manipulation of reperfusion of the myocardium by altering culture media of cultured cardiac myocytes via hypoxia/reoxygenation of the media or acidic–neutral pH perfusion [16].

Postconditioning has been shown to reduce infarct size by reducing apoptosis and necrosis, both of which presumably contribute to increased infarct size [17,18]. Postconditioning can attenuate superoxide generation in the myocardial area at risk after 3 h of reperfusion [16,17], induce antioxidant mechanisms and inhibit neutrophil adherence and accumulation in general [3]. Studies have also revealed that hypoxic postconditioning results in less intracellular and intramitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation, suggesting that triggers of MPTP opening are reduced. The MPTP opens during early reperfusion in response to oxidant and Ca2+ accumulation [19,20], initiating a cascade that results in either apoptosis or necrosis when ATP is present or depleted, respectively.

Postconditioning can also be mimicked pharmacologically by administering agents, such as inhalational anesthetics [21,22], bradykinin [23], cyclosporin A [23], erythropoietin [24], NO [25] and NO donors [26], adenosine [27], and H2S [28], at the time of reperfusion. Most of these pharmacological agents activate the RISK pathway, ultimately inhibiting MPTP opening and increasing cell survival. MPTP opening causes mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) to depolarize [29], resulting in a rapid impairment of mitochondrial function that leads to apoptotic cell death. Not surprisingly, ischemic postconditioning coupled with pharmacological postconditioning serves to reduce infarct size even more than ischemic postconditioning alone. Jiang et al. coupled postconditioning and a protease-activated receptor-2 agonist at the onset of reperfusion, and observed that infarct size was reduced to a greater extent than with either intervention alone.

Mechanisms of H2S cardioprotection in pre- & post-conditioning

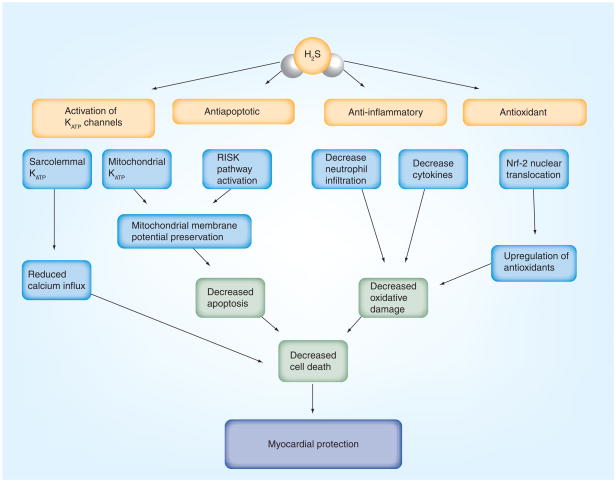

Hydrogen sulfide is a gas signaling molecule capable of physiological actions, first described as a physiological mediator in the brain in 1996 by Abe and Kimura [30] and in the cardiovascular system the following year by Hosoki, Matsuki and Kimura [31]. H2S is rapidly emerging as a novel, cytoprotective signaling molecule with potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects (Figure 1). However, at supraphysiological concentrations, H2S can be toxic and potentially lethal. H2S can reversibly inhibit the electron-transport chain [32–34], open the mitochondrial permeability transition pore [35,36], increase production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [35–38] and outcompete oxygen for hemoglobin binding [39–41].

Figure 1. Major known mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide-mediated cardioprotection.

H2S acts on sarcolemmal and mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP), reducing calcium influx into the myocardium and maintaining the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, preventing it from opening and preserving mitochondrial membrane potential, respectively. H2S has antiapoptotic effects by activating the reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway. H2S has anti-inflammatory effects by reducing cytokine levels and preventing neutrophil infiltration. H2S also has antioxidant effects, upregulating antioxidant production through Nrf-2. These combined actions of H2S serve to make it a very cardioprotective molecule.

H2S: Hydrogen sulfide; Nrf-2: Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2.

Hydrogen sulfide is a colorless, water-soluble gas, and has the characteristic smell of rotten eggs. In mammals, H2S is produced enzymatically via the cysteine metabolic enzymes cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) [30,31] and the combined actions of cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and 3-mercapto pyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) [42,43], all of which are present in the heart and vasculature [43,44]. There are several sources of H2S that are currently utilized to deliver H2S to biological systems: there is H2S gas, which can be bubbled directly into physiological saline, and two commonly used sources of H2S – sodium sulfide (Na2S) and sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS). Ikaria Holdings, Inc. (NJ, USA) has also formulated an injectable form of H2S, (i.e., IK-1001), which is pure, pH neutral and stable at room temperature.

Several studies have initially demonstrated the cardioprotective action of H2S in the setting of MI/R injury. Pretreatment with NaHS, a source of H2S, reduced the number and duration of arrhythmias in isolated rat hearts subjected to global MI/R [45]. NaHS pretreatment 10 min before coronary artery occlusion also attenuated MI/R injury in isolated, perfused rat hearts subjected to 30 min of ischemia and 2 h of reperfusion [46]. An in vivo, murine model of MI/R showed drastic reduction (56%) in infarct size after treatment with Na2S [47], while H2S treatment in a rat model of MI/R injury showed a 25% reduction in infarct size in rats pretreated with NaHS [48]. A week-long treatment of rats with NaHS showed a reduction in infarct size, as well as protection of vascular smooth muscle cells against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury [49].

Subsequent studies have started to examine the signaling mechanisms responsible for the cardioprotective actions of H2S. The presently known mechanisms of cardioprotective H2S signaling include ion channel activation and upregulation of antioxidant, antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. Each of these signaling mechanisms will be addressed in further detail in subsequent sections.

Ion channel activation & regulation

Hydrogen sulfide activates KATP channels, and this activation is responsible for a number of its physiological actions [50–54]. KATP channels are heteromeric protein complexes consisting of four pore-forming subunits that belong to the family of inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir), which are inhibited by ATP [55]. Kir6.2 is the major pore-forming subunit in cardiac cells. The Kir tetramer is also associated with four sulfonylurea receptors (SURx) that belong to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family of proteins [56,57]. KATP can be inhibited through these SURx by sulfonylureas, and activated by diazoxide (SUR1) and pinacidil (SUR2) [58].

KATP channels in the heart have long been known to play a pivotal role in the cardioprotective mechanisms of IPC, and there has been a focus on the mitochondrial KATP as well as sarcolemmal KATP [59–65]. Sivarajah et al. investigated the role of H2S in both IPC and endotoxin-mediated preconditioning using a Wistar rat model of MI/R [48]. They found a protective effect of NaHS application 15 min prior to MI/R, reducing infarct size significantly. Blockade of endogenous H2S production by the CSE inhibitor propargylglycine (PAG) increased infarct size, as did specific inhibition of the mitochondrial KATP using 5-hydroxydecanoic acid [48], indicating that endogenous cardioprotection by H2S may be mediated through mitochondrial KATP.

Sarcolemmal KATP channels also play a role in H2S-mediated cardioprotection. Opening of sarcolemmal KATP leads to potassium efflux, cell membrane depolarization and shortening of the action potential duration [66,67]. These events will reduce calcium influx, leading to a reduction of mechanical contraction and resulting in energy sparing in the myocardium during early reperfusion injury [68]. Pan et al. used isolated cardiac myocytes to investigate KATP activation and signaling in H2S preconditioning [68]. They found that 30 min of NaHS preconditioning conferred protection approximately 1 h and 16–28 h after NaHS application when cardiac myocytes were exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation injury, demonstrating that H2S has two windows of protection, similar to IPC [68]. Bian et al. also demonstrated the importance of sarcolemmal KATP channels in H2S-mediated cardioprotection in an isolated cardiac myocyte model [45]. When the sarcolemmal KATP inhibitor HMR-1098 was applied to isolated cardiac myocytes, the effects of H2S preconditioning were lost, while blockade of mitochondrial KATP with 5-hydroxydecanoic acid had no effect on the cardioprotection on H2S preconditioning [45].

Antioxidant signaling mechanisms

The antioxidant effects of H2S were first demonstrated in neuronal cells. H2S increased the transport of cysteine (substrate for glutathione [GSH] production) and cystine (dimeric cysteine), subsequently increasing the levels of GSH [69]. In HT22 neuronal cells, H2S also acts through KATP and chloride channels, in addition to GSH and cysteine regulation, to exert its antioxidant function [70]. Furthermore, H2S leads to the redistribution of GSH to the mitochondria, while direct production of H2S by CAT/3-MST may directly suppress oxidative stress [71]. Finally, H2S may also act as an antioxidant itself, as it can scavenge ROS in vitro [72].

Hydrogen sulfide preconditioning has been demonstrated by Calvert et al. to induce the translocation of the nuclear transcription factor nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) from the cytosol to the nucleus in cardiac tissue, resulting in an increase in antioxidants [73]. Nrf-2 is normally bound to Keap1 in the cytosol, but during oxidative stress, Nrf-2 is released for translocation to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, Nrf-2 binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE), which is found in the promoter region of a number of antioxidant genes. Calvert et al. demonstrated the translocation of Nrf-2 through analysis of cytosolic and nuclear protein fractions in mouse hearts collected following intravenous injection of 100 μg/kg Na2S [73]. The authors also demonstrated upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and thioredoxin (Trx)-1 and -2 at 24 h postinjection of Na2S [73]. The activation of Nrf-2 by H2S and downstream upregulation of antioxidant enzymes clearly contribute to the late phase of preconditioning.

Antiapoptotic signaling mechanisms & mitochondrial preservation

Apoptotic cell death during reperfusion is an important contributor to reperfusion-induced injury [74]. Activation of the pro-survival kinases of the RISK pathway, including PI3K, Akt, PKCε and Erk1/2, before or at the time of reperfusion, confers cardioprotection against MI/R through an inhibition of apoptosis [75]. H2S has recently been shown to modulate components of the RISK pathway [73]. Activation of the RISK pathway inhibits the opening of the MPTP, which plays a fundamental role in determining cellular survival during MI-R injury through various signaling mechanisms downstream of RISK pathway activation [76].

PI3K, Akt and PKCε signal to activate Erk1/2. Erk1/2 can then phosphorylate and inactivate the proapoptotic factor Bad through the actions of p90RSK [77]. Bad phosphorylation leads to preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential. Erk1/2 also upregulates Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, as well as heat-shock proteins (HSP90 and HSP70) through signal transducers and activators of transcription-3 (STAT-3) [78,79]. These also function to preserve the mitochondrial membrane potential, decreasing apoptotic cell death.

Calvert et al. have demonstrated that H2S upregulates multiple components of the RISK pathway in a murine model [73]. When C57BL/6J mice were injected with Na2S (100 μg/kg) and a time course was followed from 30 min, 2 h to 24 h, PKCε and Erk1/2 were upregulated 30 min to 2 h after H2S treatment [73], while the downstream effectors of Erk1/2, STAT-3, HSP90, HSP70, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and phosphorylated-Bad, were all upregulated for 24 h following H2S treatment [73].

A study in Yorkshire pigs by Osipov et al. investigating bolus or infusion of H2S at reperfusion after 1 h of ischemia demonstrated that both methods of application increased antiapoptotic signaling mechanisms, and that infusion was more effective than a bolus [80]. A bolus of H2S upregulated Erk1/2, increased phosphorylated-Bad at Ser 136 (proapoptotic, inactivated form) and decreased cleaved caspase 3 (proapoptotic, activated form) [80]. Infusion of H2S downregulated apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and both bolus and infusion increased phosphorylated GSK-3β [80]. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining for apoptotic cells showed a significant decrease in apoptotic cells in both the bolus and the infusion groups compared with control, although the infusion group showed 3.3-fold less apoptotic cells than the bolus group [80].

Both studies by Calvert et al. and Osipov et al. implicate that H2S pre- and post-conditioning may involve activation of the RISK pathway. Owing to the short and long time courses involved in the signaling, the RISK pathway may be involved in both early and late phases of preconditioning. It also appears that bolus injection and infusion of H2S have differential effects on conditioning, which may be the result of varying pathway activation by acute or chronic H2S application.

Anti-inflammatory signaling mechanisms

Hydrogen sulfide reduces proinflammatory cytokines to attenuate the inflammatory response in MI/R injury, including NF-κB, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α [81,82]. IL-6 is released in response to MI/R injury and can depress myocardial function [83,84], while IL-8 is released after MI/R injury and increases the inflammatory response, as well as neutrophil adhesion [85]. TNF-α has multiple effects exacerbating MI/R injury, including inducing endothelial adhesion molecules, enhancing neutrophil infiltration and increasing the inflammatory response [86]. TNF-α also increases the production of ROS [87], and has myocardial-depressant and apoptotic actions [88].

Some of the anti-inflammatory actions of H2S are mediated through KATP channels. H2S has been shown to inhibit leukocyte-mediated inflammation by acting upon the KATP channels [89,90]. Leukocyte infiltration through the endothelial cells into the underlying tissue is a relatively early event in the inflammatory response. Leukocytes can then generate free radicals and proteases, which are damaging to the myocardium. H2S treatment 10 min before reperfusion, and then throughout reperfusion in a swine model of MI/R, also reduced myeloperoxidase activity [81], which is a marker of leukocyte infiltration and activity. H2S donors also reduced carrageenan-induced paw edema in a dose-dependant manner that was inhibited by glibenclamide (a nonselective KATP channel blocker) and mimicked by pinacidil (a KATP agonist), suggesting that the action was through KATP channels [89].

The anti-inflammatory actions of H2S may be greatly beneficial in the setting of MI/R by maintaining coronary microvascular perfusion. Dysfunction in the microcirculation is thought to be, in part, a result of reduction in the bioavailability of NO, which is scavenged by free radicals released in the setting of MI/R injury [91]. By inhibiting neutrophil and leukocyte infiltration and repressing proinflammatory cytokines from generating excessive ROS, H2S may serve as a potent anti-inflammatory agent, helping to maintain microvascular function and myocardial blood flow following MI/R injury.

Other cytoprotective H2S signaling mechanisms

COX-2 and NO may also mediate cardioprotection induced by H2S. Hu et al. exposed isolated rat cardiac myocytes to 100 μmol/l H2S for 30 min, and then cultured them for 20 h before insulting them with hypoxia/reoxygenation injury [92]. H2S significantly increased cell viability, and this was ameliorated when inhibitors of COX-2 (NS-398 and Celecoxib) were administered [92]. H2S induced COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis in the cardiac myocytes, and these actions were blocked by glibenclamide and chelerythrine (a PKC inhibitor), suggesting that KATP and PKC are required for the stimulation of COX-2 [92]. Furthermore, they also found that L-NG nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) application inhibited COX-2 activation and PGE2 production [92]. Therefore, NO may also be involved in the H2S-mediated activation of COX-2 [92]. Calvert et al. also showed an increase in COX-2 in their in vivo model of H2S preconditioning [73]. A 100-μg/kg dose of Na2S increased COX-2 expression after 24 h [73]. Similarly, Pan et al. found that H2S may induce NO release to confer its cardio protective effects in their isolated rat cardiac myocyte model of ischemia/reperfusion injury [68]. Inhibition of NO production by L-NAME attenuated the cardioprotective effects of NaHS administration [68]. Furthermore, H2S can activate Akt in the setting of angiogenesis [93] and pre-conditioning [94]. Akt can also phosphorylate endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) to enhance the production of NO [95].

A new method of covalent protein modification by H2S, S-sulfhydration, has been described by Mustafa et al. [96]. S-sulfhydration is the process by which H2S covalently modifies cysteine residues, creating a R-SSH group. Using a modified biotinylated switch method, Mustafa et al. showed a decrease in basal S-sulfhydration in CSE−/−-knockout mice when compared with wild-type controls [96]. This indicates that basal H2S production by CSE is important in maintaining S-sulfhydration levels, and that it potentially acts as a critical pro-survival signaling event [96]. This has already been linked to a regulatory role of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, actin and tubulin, as well as the interaction of H2S with the subunits of KATP channels [96]. Since S-sulfhydration may act on proteins already expressed in the cell to change their activity, it is likely that S-sulfhydration accounts for at least some of the signaling in H2S-mediated pre- as well as post-conditioning signaling. Exploring this new mechanism of signaling may lead to further advances in understanding H2S signaling in pre- and post-conditioning.

Hydrogen sulfide is also biologically stored as bound sulfane sulfur, potentially for later release and physiological action/cytoprotection [97]. Bound sulfane sulfur is comprised of two sulfur atoms covalently bonded to each other. Examples of bound sulfane sulfur are the outer sulfur atoms of the persulfides and the inner chain atoms of polysulfides. Cysteine is metabolized via the actions of CSE, CBS and 3-MST to form H2S, which can then be incorporated into a pool of bound sulfane sulfur [98]. Exogenously applied H2S can also be absorbed into this bound sulfane sulfur pool [99].

Bound sulfane sulfur can release H2S under reducing conditions and is one of two known sulfur stores in the cell, the other being acid-labile sulfur [100,101]. Acid-labile sulfur comprises sulfur atoms in iron–sulfur complexes, which are responsible for a variety of redox reactions that occur in the mitochondrial respiratory complex enzymes. Acid-labile sulfur releases H2S below a pH of 5.4 [99]. Since the mitochondrial pH is between 7 and 8, acid-labile sulfur may not release H2S under physiologic conditions [97]. During ischemia/reperfusion injury, the myocardium will be under oxidative stress, and the required reducing conditions for the release of H2S from bound sulfane sulfur may not be met. However, during H2S-mediated pre- or post-conditioning, the upregulation of antioxidant enzymes and GSH synthesis by exogenous H2S may lead to additional H2S release from these bound sulfane sulfur stores, perpetuating the pre- and post-conditioning effects, and potentially contributing to the late phase of protection observed during preconditioning.

Connection between H2S & ischemic conditioning

Hydrogen sulfide-mediated pre- and post-conditioning are highly effective phenomena that share many similarities with their ischemic counterparts (i.e., IPC and ischemic postconditioning), including the time course and some cytoprotective signaling pathways. However, very little is currently known of the mechanisms by which H2S conditions the myocardium, and it remains to be seen how far ischemic conditioning and H2S overlap in their signaling. For example, IPC may work, in part, through H2S signaling. The concept that H2S works depending on the local oxygen tension has been proposed in several papers by Olson et al. and Whitfield et al. [102–105]. If this is the case, then ischemic preconditioning may induce increases in local H2S concentrations by transiently creating a low-oxygen environment that favors the formation of H2S. This increase in local H2S may mimic the effect of exogenous application. So far, investigation into H2S concentration in a non-mammalian, vertebrate heart using a polarographic, H2S-specific electrode revealed an increase in H2S during exposure to hypoxic conditions [105]. While this remains to be validated and expanded in mammalian models, some studies have already begun to link H2S and IPC in mammalian systems [48,68]. Additionally, the use of DL-propargylglycine and β-cyano-L-alanine, inhibitors of H2S synthesis, during metabolic ischemic preconditioning significantly reduced the effectiveness of the preconditioning protocol, which supports the idea that endogenous H2S contributes to preconditioning [68].

Furthermore, there are both direct and indirect mechanisms by which H2S can act as a cardioprotectant. While direct actions of H2S on ROS or leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions, for example, contribute to cardioprotection, they may not necessarily be responsible for the pre- or post-conditioning induced by H2S. Activation of the RISK pathway or Nrf-2 translocation may serve to precondition the heart, since these mechanisms require more time to become fully activated. The concentration(s) of H2S at which these direct actions and conditioning actions occur should also be considered. While a specific study on this has not been conducted, we know there is activation of the RISK pathway and Nrf-2 translocation at doses of Na2S 100 μg/kg [73]. However, significant cardioprotection can be produced at doses of Na2S 50 μg/kg [44].

Endogenous H2S & cardiovascular disease

Decreases in H2S are associated with the pathology of a number of cardiovascular and related diseases, including hypertension and diabetes. H2S has also been implicated in vasodilation of the corpus cavernosum [106–108] and the dysregulation of H2S has been linked to erectile dysfunction [109].

The dysregulation of H2S that occurs in these pathologies is predominantly a decrease in endogenous H2S, implying that a basal level of H2S is very important for cardiovascular homeostasis. Spontaneously hypertensive rats also have reduced H2S levels in their blood, and CSE−/− mice display an increase in blood pressure as they age [110,111]. In nonobese diabetic mice, endogenous H2S levels decrease and endogenous production is impaired with an increase in severity of the disease pathology [112]. This study also suggests that NO may be involved in the enzymatic conversion of L-cysteine to H2S in the cardiovascular system [112]. CSE contains 12 cysteine residues that may be the target of S-nitrosylation, potentially enhancing its activity [113]. If this is the case, then diseases that involve endothelial dysfunction (resulting in decreased endogenous NO production) actually involve the functional loss of two key gasotransmitters (H2S and NO). Furthermore, endogenous H2S also declines in obese and diabetic humans [114,115].

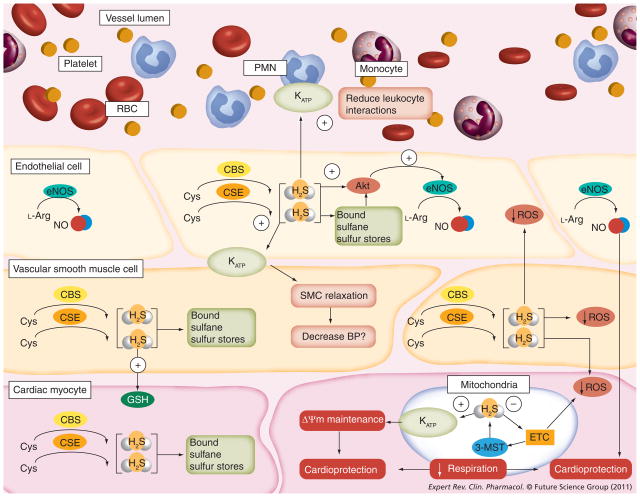

The dysregulation of H2S, particularly the loss of bio available H2S or the capacity for endogenous production, has several impacts on cardiovascular disease. The endogenous production of H2S is likely critical in maintaining basal antioxidant defenses and mitochondrial membrane potential and is instrumental in resisting inflammation and the tonic regulation of blood vessels (Figure 2). As the endogenous level of H2S declines, all of these functions will become compromised. This will ultimately result in an increased susceptibility to cell death following reperfusion of an ischemic heart and an increase in morbidity and mortality. This dysregulation may be exacerbated by age, as there is evidence that H2S bioavailability, like NO, decreases with age [116].

Figure 2. Endogenous H2S signaling contributes to cardiovascular homeostasis.

Endogenous H2S is produced from CSE, CBS or 3-MST. Excess H2S produced is stored in the cell as bound sulfane sulfur. H2S may act through Akt to phosphorylate eNOS, in turn upregulating production of the cardioprotective gas, NO, from Arg. H2S increases glutathione production, and can act on vascular smooth muscle KATP to cause SMC relaxation and a decrease in BP. H2S also acts on the KATP channels of leukocytes (i.e., polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes) to prevent rolling, adhesion and transmigration through the endothelial cell layer. H2S can scavenge free radicals that are produced from the mitochondria, and activate mitochondrial KATP channels, which may contribute to maintenance of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and cardioprotection. H2S also decreases respiration by inhibiting the electron transport chain, which also leads to cardioprotection.

3-MST: 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; BP: Blood pressure; CBS: Cystathionine β-synthase; CSE: Cystathionine γ-lyase; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ETC: Electron transport chain; GSH: Glutathione; H2S: Hydrogen sulfide; KATP: ATP-sensitive potassium channels; L-Arg: L-arginine; NO: Nitric oxide; PMN: Polymorphonuclear leukocyte; RBC: Red blood cell; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SMC: Smooth muscle cell.

Clinical translation of H2S

Clinical use of IPC for the heart

Even though IPC is the most potent and reproducible phenomenon in cardioprotection, it has not been readily translated to clinical use [117]. A major issue in IPC is that the timing of the main ischemic event must be known ahead of time for IPC to be effectively applied. Unfortunately, there is no way to predict when a myocardial infarction will occur and, therefore, no way to induce IPC just before the infarction. However, in scenarios when the ischemic event is known, such as elective coronary artery balloon angioplasty, coronary bypass surgery or heart transplantation, preconditioning can be effectively employed. Here, invasive measures can be taken to induce IPC via balloon inflation or cross clamping. Yellon et al. were the first to demonstrate the feasibility of IPC in the human heart during cardiac surgery [118]. In their study, to achieve IPC, the heart was subjected to two periods of crossclamping, and preserved myocardial ATP levels were used as an index of myocardial protection [118]. The two periods of crossclamping significantly preserved the myocardial ATP levels following a prolonged period of ischemia, suggesting that the hearts would exhibit a greater tolerance to MI/R injury [118].

A noninvasive form of IPC has been developed as remote ischemic preconditioning (RIP). RIP is based on the idea that one vascular bed may precondition another vascular bed. The initial study into RIP was carried out by Przyklenk et al. in 1993 [119]. Przyklenk et al. demonstrated in a canine model that preconditioning the opposite coronary bed reduced myocardial infarct size to the same extent as preconditioning in the same coronary bed [119]. This concept was followed by additional studies that suggested remote organ ischemia, such as the kidney or mesentery, could also confer protection to the myocardium [117]. Remote limb ischemia also effectively preconditions the myocardium. Birnbaum et al. published the first study in a rabbit model that suggested that transient limb ischemia could be used in RIP [120]. Subsequent studies in humans showed that transient limb ischemia protects against endothelial ischemic reperfusion injury of the opposite limb [121], and reduces myocardial ischemic damage during coronary artery bypass surgery [122] and during pediatric cardiac surgery [123].

Preconditioning mimetics can also be used to mimic IPC. These can be proactively applied in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease or in patients that will undergo elective surgical procedures, such as organ transplantation or cardiac bypass surgery, that involve a defined ischemia/reperfusion injury. H2S may potentially fulfil this role as well, as there is accumulating evidence in animal models that it can be used as a preconditioning agent. However, this has yet to be demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial (see below).

Clinical use of postconditioning for the heart

Postconditioning is easier to apply clinically, as the time of ischemia does not have to be known ahead of time since the conditioning begins after reperfusion. Clinical use of postconditioning thus far has largely been done in several smaller proof-of-concept trials. However, the results are very encouraging [3]. Seven prospective randomized trials have investigated postconditioning in percutaneous coronary intervention, totaling 353 patients [124–130].

These clinical studies have used varying intervals of postconditioning, ranging from two to four cycles of 30 to 90 s per cycle [124–130]. All of the studies consistently showed a protective effect of postconditioning, even though their conditioning protocols varied [124–130]. Various markers of improvement were measured and showed protection: infarct size was decreased [127], ejection fraction increased by postconditioning [127,128], ST-segment resolution was increased in those who underwent postconditioning [124,129] and serum markers of cardiac damage, such as creatine kinase and troponin-I, were also decreased in postconditioning groups [125–128] in addition to the proapoptotic serum marker sFasL [130].

Translation of H2S to the clinic

There are three clinical trials currently ongoing that involve H2S and H2S therapy. An observational study at University Medical Center in Ljubljana, Slovenia, is investigating H2S as a prognostic factor in shock by measuring serum levels of H2S upon admission in the intensive care unit. The aim is to link the serum levels of H2S with a higher mortality in patients with shock. Ikaria Holdings, Inc. has two ongoing clinical trials. Both of these trials will use IK-1001 as a source of injectable H2S. The first study, taking place in the USA, is a Phase I study to assess the pharmacokinetics of IK-1001 in healthy subjects and in those with renal impairment of various degrees (mild–severe). All subjects will receive the drug as a single intravenous infusion. The second study, taking place at several locations in Australia and Canada, is a Phase II clinical trial that will investigate the safety and effectiveness of IK-1001 when used in coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) patients to reduce the damage done to the heart during surgery. The randomly assigned subjects will also receive IK-1001 as an intravenous infusion while they are undergoing CABG surgery.

Use of H2S therapy in cardiac surgery

Hydrogen sulfide is beginning to be translated to a surgical setting. However, the chemical properties of H2S, namely high reactivity and potential toxicity, pose a challenge when administering H2S in vitro or in vivo. IK-1001 has shown promising effects in preconditioning and in reducing infarct size after MI/R in murine models [44,73]. However, H2S generated from solutions of Na2S can be rapidly oxidized once liberated in the presence of molecular oxygen and trace metals [38], conditions that are ubiquitous in most experimental models and in the human body. Therefore, a stable source of H2S that can be released at the intended site of action would be desired. A H2S-releasing derivative of diclofenac (S-diclofenac) has been shown recently to have cardioprotective actions in an isolated rabbit heart model [131]. Rossoni et al. showed that S-diclofenac achieved a dose-dependant normalization of coronary perfusion pressure, as well as reduced levels of creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase, and increased levels of GSH in the perfusate [131]. Additionally, there are several currently available options to fill this role, such as organic polysulfides, molecules with chains of sulfur atoms between two functional groups. Diallyl disulfide and diallyl trisulfide are garlic-derived organic polysulfides that act as stable H2S donors when they react with biological thiols, such as GSH [132,133].

Hydrogen sulfide donors may play an important role in cardiac surgery, where damage to the heart and ischemia happen at a largely predictable time. H2S donors could be administered 24 h preoperatively to invoke delayed or late preconditioning cytoprotective signaling cascades if the surgery was not time critical, or right before or during ischemia to invoke the early pre- and post-conditioning signaling cascades. It will be exciting to see the results of the Ikaria trial in CABG patients, which may pave the way for future clinical trials using H2S as a pre- and postconditioning agent during other procedures, such as balloon angioplasty, stenting or transplantation.

Summary

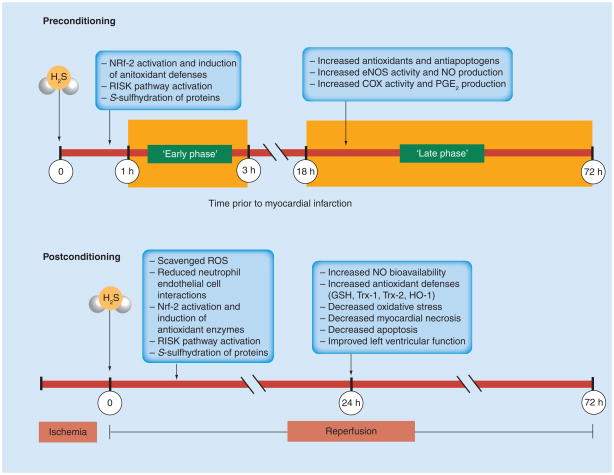

It is clear that H2S can be used as an effective preconditioning and postconditioning agent. However, it is currently difficult to define the precise mechanisms for this protection. A summary of the known mechanisms by which H2S-induced pre- and post-conditioning may work is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Hydrogen sulfide as a pre- and post-conditioning agent.

In the early phase of preconditioning, H2S can activate the Nrf-2, and subsequently induce antioxidant defenses in the late phase. H2S also activates the RISK pathway leading to antiapoptogen and antioxidant increases in the late phase. H2S may also act through S-sulfhydration, activating several molecular targets already present in the myocardium, which may lead to early-phase protection. H2S also leads to increased eNOS activity and NO production, as well as increased COX and PGE2 production, which may contribute to the late phase. In postconditioning, H2S can readily scavenge ROS produced during reperfusion and reduce neutrophile–endothelial cell interactions. H2S will also activate Nrf-2 translocation and the RISK pathway, and may act through S-sulfhydration of proteins. During later reperfusion, H2S preconditioning will result in increased NO bioavailability and antioxidant defenses, such as GSH, Trx-1 and -2 and HO-1. There is a resulting reduction in oxidative stress, as well as in myocardial necrosis and apoptosis, which, ultimately, results in improved left ventricular function.

eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GSH: Glutathione; H2S: Hydrogen sulfide; HO-1: Heme oxygenase-1; NO: Nitric oxide; Nrf-2: Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; PGE2: Prostaglandin E2; RISK: Reperfusion injury salvage kinase; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; Trx: Thioredoxin.

In the early phase of preconditioning, H2S can activate Nrf-2, and subsequently induce antioxidant defenses in the late phase. H2S also activates the RISK pathway, leading to antiapoptogen and antioxidant increases in the late phase. H2S may also act through S-sulfhydration, activating several molecular targets already present in the myocardium, which may lead to early-phase protection. H2S leads to increased eNOS activity and NO production, as well as increased COX and PGE2 production, which may contribute to the late phase. In postconditioning, H2S can readily scavenge ROS produced during reperfusion and reduce neutrophil–endothelial cell interactions. H2S will also activate Nrf-2 translocation and the RISK pathway, and may act through S-sulfhydration of proteins. During later reperfusion, H2S preconditioning will result in increased NO bioavailability and antioxidant defenses, such as GSH, Trx-1 and -2 and HO-1. There is a resulting reduction in oxidative stress, as well as in myocardial necrosis and apoptosis, which ultimately results in improved left ventricular function.

Expert commentary

Hydrogen sulfide has great potential as a pre- and post-conditioning agent. While the exact mechanisms behind its cardioprotective effects are not entirely known, thus far, it has been efficacious in small-animal research and some pioneering large-animal work. Current clinical trials and future translational research will shed light on the efficacy of H2S as a cytoprotective agent in humans during ischemic injury, while more basic science research will be needed to uncover the H2S signaling pathways that confer cytoprotection in the ischemic myocardium in order to fully realize its therapeutic potential. Additionally, to aid in clinical translation and address human complexity, research needs to include models of comorbid conditions that may modify the cardioprotective signaling, such as dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, diabetes and age.

Five-year view

The future looks bright for H2S as a pre- and post-conditioning agent. There are several drugs and donor agents that are available for research purposes, and some are even undergoing clinical trials. Ideally, several stable donors of H2S would be available in the next 5 years for use in clinical research trials, particularly in cardiac surgery and other surgical applications where ischemia/reperfusion injury is prevalent, such as organ transplantation. There have already been multiple patents filed on potential H2S-releasing drugs [134,135]. New, stable H2S donors will also allow further elucidation of the many signaling mechanisms involved in the cardioprotective actions of H2S in experimental models, which can then be translated to the clinic.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@expert-reviews.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by NIH grants 5R01 HL092141–02 and NIH 1R01 HL093579–01A1 to David J Lefer and the Carlye Fraser Heart Center (CFHC) of Emory University Hospital Midtown. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Assmann G, Cullen P, Jossa F, Lewis B, Mancini M. Coronary heart disease: reducing the risk: the scientific background to primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. A worldwide view International Task force for the Prevention of Coronary Heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(8):1819–1824. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausenloy DJ, Tsang A, Yellon DM. The reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway: a common target for both ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15(2):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granfeldt A, Lefer DJ, Vinten-Johansen J. Protective ischaemia in patients: preconditioning and postconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83(2):234–246. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74(5):1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolli R, Li QH, Tang XL, et al. The late phase of preconditioning and its natural clinical application – gene therapy. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12(3–4):189–199. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolli R. Cardioprotective function of inducible nitric oxide synthase and role of nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia and preconditioning: an overview of a decade of research. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(11):1897–1918. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tritto I, Ambrosio G. Role of oxidants in the signaling pathway of preconditioning. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3(1):3–10. doi: 10.1089/152308601750100425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MV, Yang XM, Liu GS, Heusch G, Downey JM. Acetylcholine, bradykinin, opioids, and phenylephrine, but not adenosine, trigger preconditioning by generating free radicals and opening mitochondrial K(ATP) channels. Circ Res. 2001;89(3):273–278. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu GS, Thornton J, Van Winkle DM, et al. Protection against infarction afforded by preconditioning is mediated by A1 adenosine receptors in rabbit heart. Circulation. 1991;84(1):350–356. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz JE, Rose E, Yao Z, Gross GJ. Evidence for involvement of opioid receptors in ischemic preconditioning in rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(5 Pt 2):H2157–H2161. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marber MS, Latchman DS, Walker JM, Yellon DM. Cardiac stress protein elevation 24 hours after brief ischemia or heat stress is associated with resistance to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993;88(3):1264–1272. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Na HS, Kim YI, Yoon YW, et al. Ventricular premature beat-driven intermittent restoration of coronary blood flow reduces the incidence of reperfusion-induced ventricular fibrillation in a cat model of regional ischemia. Am Heart J. 1996;132(1 Pt 1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao ZQ, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, et al. Inhibition of myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion: comparison with ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(2):H579–H588. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Corvera JS, et al. Myocardial protection with postconditioning is not enhanced by ischemic preconditioning. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(3):961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skyschally A, van Caster P, Boengler K, et al. Ischemic postconditioning in pigs: no causal role for RISK activation. Circ Res. 2009;104(1):15–18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun HY, Wang NP, Kerendi F, et al. Hypoxic postconditioning reduces cardiomyocyte loss by inhibiting ROS generation and intracellular Ca2+ overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(4):H1900–H1908. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01244.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kin H, Wang NP, Mykytenko J, et al. Inhibition of myocardial apoptosis by postconditioning is associated with attenuation of oxidative stress-mediated nuclear factor-κB translocation and TNF α release. Shock. 2007;29(6):761–768. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31815cfd5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun HY, Wang NP, Halkos M, et al. Postconditioning attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via inhibition of JNK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Apoptosis. 2006;11(9):1583–1593. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-9037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Lisa F, Canton M, Menabo R, Dodoni G, Bernardi P. Mitochondria and reperfusion injury. The role of permeability transition. Basic Res Cardiol. 2003;98(4):235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halestrap AP, Kerr PM, Javadov S, Woodfield KY. Elucidating the molecular mechanism of the permeability transition pore and its role in reperfusion injury of the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366(1–2):79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng J, Lucchinetti E, Ahuja P, et al. Isoflurane postconditioning prevents opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore through inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(5):987–995. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber NC, Preckel B, Schlack W. The effect of anaesthetics on the myocardium – new insights into myocardial protection. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005;22(9):647–657. doi: 10.1017/s0265021505001080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim SY, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Preconditioning and postconditioning: the essential role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(3):530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mudalagiri NR, Mocanu MM, Di Salvo C, et al. Erythropoietin protects the human myocardium against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and ERK1/2 activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(1):50–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson G, 3rd, Tsao PS, Lefer AM. Cardioprotective effects of authentic nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia with reperfusion. Crit Care Med. 1991;19(2):244–252. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199102000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefer DJ, Nakanishi K, Johnston WE, Vinten-Johansen J. Antineutrophil and myocardial protecting actions of a novel nitric oxide donor after acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion of dogs. Circulation. 1993;88(5 Pt 1):2337–2350. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budde JM, Velez DA, Zhao Z, et al. Comparative study of AMP579 and adenosine in inhibition of neutrophil-mediated vascular and myocardial injury during 24 h of reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47(2):294–305. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefer DJ. A new gaseous signaling molecule emerges: cardioprotective role of hydrogen sulfide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(46):17907–17908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Akar FG, O’Rourke B. Mitochondrial criticality: a new concept at the turning point of life or death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762(2):232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci. 1996;16(3):1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. First study to propose that hydrogen sulfide could be an endogenous, gaseous signaling molecule and provide physiological evidence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237(3):527–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholls P. The effect of sulphide on cytochrome aa3. Isosteric and allosteric shifts of the reduced α-peak. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;396(1):24–35. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(75)90186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan AA, Schuler MM, Prior MG, et al. Effects of hydrogen sulfide exposure on lung mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;103(3):482–490. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90321-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholls P, Kim JK. Sulphide as an inhibitor and electron donor for the cytochrome c oxidase system. Can J Biochem. 1982;60(6):613–623. doi: 10.1139/o82-076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Julian D, April KL, Patel S, Stein JR, Wohlgemuth SE. Mitochondrial depolarization following hydrogen sulfide exposure in erythrocytes from a sulfide-tolerant marine invertebrate. J Exp Biol. 2005;208(Pt 21):4109–4122. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eghbal MA, Pennefather PS, O’Brien PJ. H2S cytotoxicity mechanism involves reactive oxygen species formation and mitochondrial depolarisation. Toxicology. 2004;203(1–3):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen KY, Morris JC. Oxidation of sulfide by O2: catalysis and inhibition. J San Eng Div Proc Am Soc Civ Eng. 1972;98:215–227. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tapley DW, Beuttner GR, Shick JM. Free radicals and chemiluminescence as products of the spontaneous oxidation of sulfide in seawater, and their biological implications. Biol Bull. 1999;196:52–56. doi: 10.2307/1543166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagarinao T, Vetter RD. Sulfide-hemoglobin interactions in the sulfide-tolerant salt-marsh resident, the California killifish Fundulus parvipinnis. J Comp Physiol B. 1992;162:614–624. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraus DW, Doeller JE, Powell CS. Sulfide may directly modify cytoplasmic hemoglobin deoxygenation in Solemya reidi gills. J Exp Biol. 1996;199:1343–1352. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.6.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Völkel S, Berenbrink MK. Sulphaemoglobin formation in fish: a comparison between the haemoglobin of the sulphide-sensitive rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and of the sulphide-tolerant common carp (Cyprinus carpio) J Exp Biol. 2000;203:1047–1058. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42•.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, et al. 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(4):703–714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2253. Shows a new pathway for the production of hydrogen sulfide that is physiologically relevant in mammals, in addition to cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, Nagahara N, Kimura H. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide. J Biochem. 2009;146(5):623–626. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(39):15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. Demonstrates that both exogenously applied and endogenous hydrogen sulfide are cardioprotective in the heart. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bian JS, Yong QC, Pan TT, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the cardioprotection caused by ischemic preconditioning in the rat heart and cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316(2):670–678. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansen D, Ytrehus K, Baxter GF. Exogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) protects against regional myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury – evidence for a role of KATP channels. Basic Res Cardiol. 2006;101(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Duranski MR, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide donor protects against acute myocardial ischemia– reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2006;114(18 Suppl S):172. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sivarajah A, McDonald MC, Thiemermann C. The production of hydrogen sulfide limits myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury and contributes to the cardioprotective effects of preconditioning with endotoxin, but not ischemia in the rat. Shock. 2006;26(2):154–161. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225722.56681.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu YZ, Wang ZJ, Ho P, et al. Hydrogen sulfide and its possible roles in myocardial ischemia in experimental rats. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(1):261–268. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00096.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng Y, Ndisang JF, Tang G, Cao K, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide-induced relaxation of resistance mesenteric artery beds of rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(5):H2316–H2323. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00331.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geng B, Yang J, Qi Y, et al. H2S generated by heart in rat and its effects on cardiac function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313(2):362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kubo S, Kajiwara M, Kawabata A. Dual modulation of the tension of isolated gastric artery and gastric mucosal circulation by hydrogen sulfide in rats. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15(6):288–292. doi: 10.1007/s10787-007-1590-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang W, Yang G, Jia X, Wu L, Wang R. Activation of KATP channels by H2S in rat insulin-secreting cells and the underlying mechanisms. J Physiol. 2005;569(Pt 2):519–531. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S as a novel endogenous gaseous KATP channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20(21):6008–6016. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Babenko AP, Gonzalez GC, Bryan J. Hetero-concatemeric KIR6.X4/SUR14 channels display distinct conductivities but uniform ATP inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(41):31563–31566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shyng S, Nichols CG. Octameric stoichiometry of the KATP channel complex. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110(6):655–664. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clement JP, 4th, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, et al. Association and stoichiometry of KATP channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;18(5):827–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440(7083):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Das B, Sarkar C. Is the sarcolemmal or mitochondrial K(ATP) channel activation important in the antiarrhythmic and cardioprotective effects during acute ischemia/reperfusion in the intact anesthetized rabbit model? Life Sci. 2005;77(11):1226–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garlid KD, Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, et al. Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide and its interaction with mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Circ Res. 1997;81(6):1072–1082. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hide EJ, Thiemermann C. Limitation of myocardial infarct size in the rabbit by ischaemic preconditioning is abolished by sodium 5-hydroxydecanoate. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;31(6):941–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hide EJ, Thiemermann C. Sulprostone-induced reduction of myocardial infarct size in the rabbit by activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118(6):1409–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carroll R, Yellon DM. Delayed cardioprotection in a human cardiomyocyte-derived cell line: the role of adenosine, p38MAP kinase and mitochondrial KATP. Basic Res Cardiol. 2000;95(3):243–249. doi: 10.1007/s003950050187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Downey JM, Cohen MV. Do mitochondrial KATP channels serve as triggers rather than end-effectors of ischemic preconditioning’s protection? Basic Res Cardiol. 2000;95(4):272–274. doi: 10.1007/s003950070045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pain T, Yang XM, Critz SD, et al. Opening of mitochondrial KATP channels triggers the preconditioned state by generating free radicals. Circ Res. 2000;87(6):460–466. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cole WC, McPherson CD, Sontag D. ATP-regulated K+ channels protect the myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion damage. Circ Res. 1991;69(3):571–581. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noma A. ATP-regulated K+ channels in cardiac muscle. Nature. 1983;305(5930):147–148. doi: 10.1038/305147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan TT, Feng ZN, Lee SW, Moore PK, Bian JS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to the cardioprotection by metabolic inhibition preconditioning in the rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40(1):119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kimura Y, Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide protects neurons from oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2004;18(10):1165–1167. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1815fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kimura Y, Dargusch R, Schubert D, Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide protects HT22 neuronal cells from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(3–4):661–670. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kimura Y, Goto Y, Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide increases glutathione production and suppresses oxidative stress in mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12(1):1–13. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whiteman M, Armstrong JS, Chu SH, et al. The novel neuromodulator hydrogen sulfide: an endogenous peroxynitrite ‘scavenger’? J Neurochem. 2004;90(3):765–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73••.Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105(4):365–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. Lays down the groundwork for the cardioprotective signaling mechanisms of hydrogen sulfide through Nrf-2 and the RISK pathway. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. New directions for protecting the heart against ischaemia-reperfusion injury: targeting the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK)- pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61(3):448–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yellon DM, Baxter GF. Reperfusion injury revisited: is there a role for growth factor signaling in limiting lethal reperfusion injury? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1999;9(8):245–249. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Churchill EN, Mochly-Rosen D. The roles of PKCδ and ε isoenzymes in the regulation of myocardial ischaemia/ reperfusion injury. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 5):1040–1042. doi: 10.1042/BST0351040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bertolotto C, Maulon L, Filippa N, Baier G, Auberger P. Protein kinase C τ and ε promote T-cell survival by a RSK-dependent phosphorylation and inactivation of BAD. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(47):37246–37250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):281–294. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Madamanchi NR, Li S, Patterson C, Runge MS. Thrombin regulates vascular smooth muscle cell growth and heat shock proteins via the JAK–STAT pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(22):18915–18924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80•.Osipov RM, Robich MP, Feng J, et al. Effect of hydrogen sulfide in a porcine model of myocardial ischemia/ reperfusion: comparison of different administration regimens and characterization of the cellular mechanisms of protection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54(4):287–297. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181b2b72b. Takes small-animal research to the next level using a translational model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in the pig. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sodha NR, Clements RT, Feng J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates the inflammatory response in a porcine model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138(4):977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oh GS, Pae HO, Lee BS, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits nitric oxide production and nuclear factor-κB via heme oxygenase-1 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41(1):106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kukielka GL, Smith CW, Manning AM, et al. Induction of interleukin-6 synthesis in the myocardium. Potential role in postreperfusion inflammatory injury. Circulation. 1995;92(7):1866–1875. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hennein HA, Ebba H, Rodriguez JL, et al. Relationship of the proinflammatory cytokines to myocardial ischemia and dysfunction after uncomplicated coronary revascularization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(4):626–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kukielka GL, Smith CW, LaRosa GJ, et al. Interleukin-8 gene induction in the myocardium after ischemia and reperfusion in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(1):89–103. doi: 10.1172/JCI117680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dinarello CA. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;118(2):503–508. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nian M, Lee P, Khaper N, Liu P. Inflammatory cytokines and postmyocardial infarction remodeling. Circ Res. 2004;94(12):1543–1553. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130526.20854.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Herrera-Garza EH, Stetson SJ, Cubillos- Garzon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α: a mediator of disease progression in the failing human heart. Chest. 1999;115(4):1170–1174. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zanardo RC, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. FASEB J. 2006;20(12):2118–2120. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6270fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang H, Zhi L, Moochhala SM, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulates leukocyte trafficking in cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(4):894–905. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prasad A, Gersh BJ. Management of microvascular dysfunction and reperfusion injury. Heart. 2005;91(12):1530–1532. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.064485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hu LF, Pan TT, Neo KL, Yong QC, Bian JS. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates the delayed cardioprotection induced by hydrogen sulfide preconditioning in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455(6):971–978. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cai WJ, Wang MJ, Moore PK, et al. The novel proangiogenic effect of hydrogen sulfide is dependent on Akt phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yong QC, Lee SW, Foo CS, et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulphide mediates the cardioprotection induced by ischemic postconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(3):H1330–H1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00244.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, et al. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399(6736):601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96•.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, et al. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal. 2009;2(96):ra72. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000464. Investigates a novel mechanism of signaling for hydrogen sulfide, S-sulfhydration, which is similar to nitrosylation by nitric oxide. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide: its production, release and functions. Amino Acids. doi: 10.1007/s00726–010–0510-x (2010). (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Daniels KM, Stipanuk MH. The effect of dietary cysteine level on cysteine metabolism in rats. J Nutr. 1982;112(11):2130–2141. doi: 10.1093/jn/112.11.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ishigami M, Hiraki K, Umemura K, et al. A source of hydrogen sulfide and a mechanism of its release in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(2):205–214. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, Togawa T, Tanabe S. Determination of bound sulfur in serum by gas dialysis/high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1993;215(1):73–81. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Toohey JI. Sulphane sulphur in biological systems: a possible regulatory role. Biochem J. 1989;264(3):625–632. doi: 10.1042/bj2640625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Olson KR. Hydrogen sulfide and oxygen sensing: implications in cardiorespiratory control. J Exp Biol. 2008;211(Pt 17):2727–2734. doi: 10.1242/jeb.010066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Olson KR, Dombkowski RA, Russell MJ, et al. Hydrogen sulfide as an oxygen sensor/transducer in vertebrate hypoxic vasoconstriction and hypoxic vasodilation. J Exp Biol. 2006;209(Pt 20):4011–4023. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Olson KR, Forgan LG, Dombkowski RA, Forster ME. Oxygen dependency of hydrogen sulfide-mediated vasoconstriction in cyclostome aortas. J Exp Biol. 2008;211(Pt 14):2205–2213. doi: 10.1242/jeb.016766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, Skovgaard N, Olson KR. A reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:1930–1937. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.d’Emmanuele di Villa Bianca R, Sorrentino R, Maffia P, et al. Hydrogen sulfide as a mediator of human corpus cavernosum smooth-muscle relaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(11):4513–4518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Srilatha B, Adaikan PG, Li L, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulphide: a novel endogenous gasotransmitter facilitates erectile function. J Sex Med. 2007;4(5):1304–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shukla N, Rossoni G, Hotston M, et al. Effect of hydrogen sulphide-donating sildenafil (ACS6) on erectile function and oxidative stress in rabbit isolated corpus cavernosum and in hypertensive rats. BJU Int. 2009;103(11):1522–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Srilatha B, Adaikan PG, Moore PK. Possible role for the novel gasotransmitter hydrogen sulphide in erectile dysfunction – a pilot study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;535(1–3):280–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Du J, Yan H, Tang C. Endogenous H2S is involved in the development of spontaneous hypertension. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2003;35(1):102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang G, Wu L, Jiang B, et al. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine γ-lyase. Science. 2008;322(5901):587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brancaleone V, Roviezzo F, Vellecco V, et al. Biosynthesis of H2S is impaired in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155(5):673–680. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Koenitzer JR, Isbell TS, Patel HD, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates vasoactivity in an O2-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(4):H1953–H1960. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01193.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jain SK, Bull R, Rains JL, et al. Low levels of hydrogen sulfide in the blood of diabetes patients and streptozotocin-treated rats causes vascular inflammation? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12(11):1333–1337. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Whiteman M, Gooding KM, Whatmore JL, et al. Adiposity is a major determinant of plasma levels of the novel vasodilator hydrogen sulphide. Diabetologia. 2010;53(8):1722–1726. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Predmore BL, Alendy MJ, Ahmed KI, Leeuwenburgh C, Julian D. The hydrogen sulfide signaling system: changes during aging and the benefits of caloric restriction. Age. 2010;32(4):467–481. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9150-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kloner RA. Clinical application of remote ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 2009;119(6):776–778. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yellon DM, Alkhulaifi AM, Pugsley WB. Preconditioning the human myocardium. Lancet. 1993;342(8866):276–277. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Przyklenk K, Bauer B, Ovize M, Kloner RA, Whittaker P. Regional ischemic ‘preconditioning’ protects remote virgin myocardium from subsequent sustained coronary occlusion. Circulation. 1993;87(3):893–899. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Birnbaum Y, Hale SL, Kloner RA. Ischemic preconditioning at a distance: reduction of myocardial infarct size by partial reduction of blood supply combined with rapid stimulation of the gastrocnemius muscle in the rabbit. Circulation. 1997;96(5):1641–1646. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kharbanda RK, Mortensen UM, White PA, et al. Transient limb ischemia induces remote ischemic preconditioning in vivo. Circulation. 2002;106(23):2881–2883. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043806.51912.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hausenloy DJ, Mwamure PK, Venugopal V, et al. Effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on myocardial injury in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9587):575–579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cheung MM, Kharbanda RK, Konstantinov IE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of remote ischemic preconditioning on children undergoing cardiac surgery: first clinical application in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(11):2277–2282. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Laskey WK. Brief repetitive balloon occlusions enhance reperfusion during percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: a pilot study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65(3):361–367. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Staat P, Rioufol G, Piot C, et al. Postconditioning the human heart. Circulation. 2005;112(14):2143–2148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ma XJ, Zhang XH, Li CM, Luo M. Effect of postconditioning on coronary blood flow velocity and endothelial function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2006;40(6):327–333. doi: 10.1080/14017430601047864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yang XC, Liu Y, Wang LF, et al. Reduction in myocardial infarct size by postconditioning in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2007;19(10):424–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Thibault H, Piot C, Ovize M. Postconditioning in man. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12(3–4):245–248. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Laskey WK, Yoon S, Calzada N, Ricciardi MJ. Concordant improvements in coronary flow reserve and ST-segment resolution during percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: a benefit of postconditioning. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72(2):212–220. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhao WS, Xu L, Wang LF, et al. A 60-s postconditioning protocol by percutaneous coronary intervention inhibits myocardial apoptosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Apoptosis. 2009;14(10):1204–1211. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rossoni G, Sparatore A, Tazzari V, et al. The hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of diclofenac protects against ischaemia– reperfusion injury in the isolated rabbit heart. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(1):100–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]