N-cadherin is necessary in melanotropes and corticotropes for maintaining adherens junction protein expression at the cell membrane. Loss of N-cadherin leads to aberrant corticotrope clustering.

Abstract

Pituitary tumors are the third most common intracranial tumor in humans and can cause altered hormone secretions leading to hypercortisolism, acromegaly, and infertility. Reduced expression of the cell adhesion molecule N-cadherin has been linked with the formation of pituitary tumors, but its role in normal pituitary gland physiology or tumor initiation is unknown. In the murine pituitary, N-cadherin expression is detected in virtually all cells of the posterior, intermediate, and anterior lobes. N-cadherin may function to initiate important cues such as controlling proliferation, directing cell placement, and promoting formation of cell networks that coordinately release hormones into the bloodstream. To address this, we generated mice lacking N-cadherin in proopiomelanocortin-expressing melanotrope and corticotrope cells of the intermediate and anterior lobes of the pituitary. We observed that intermediate lobe cells can aberrantly displace SOX2-containing progenitor cells in the N-cadherin conditional knockout mice at postnatal d 1. By postnatal d 30, although a reduction in α- and β-catenin membrane staining occurs, there is little effect on intermediate lobe architecture with N-cadherin loss. Also, despite these changes in adherens junction molecules, no alterations in cell proliferation occur. In contrast, loss of N-cadherin in the corticotropes leads to aberrant cell clustering and a reduction in Pomc mRNA. Taken together, our data reveal important roles of N-cadherin in pituitary cell placement and that loss of N-cadherin alone does not lead to pituitary tumor formation.

The pituitary is responsible for producing hormones that mediate diverse physiological processes. It does this through the actions of cell populations within its three distinct lobes. The posterior lobe (PL), derived from neural ectoderm, contains pituicytes and axon terminals of magnocellular neurons. The anterior lobe (AL) is composed of corticotropes, thyrotropes, somatotropes, lactotropes, and gonadotropes, whereas the intermediate lobe (IL) contains melanotropes. During embryonic development, the hormone-producing cells of the AL and IL arise from undifferentiated progenitor cells that divide in Rathke's pouch, which is derived from the oral ectoderm. These cells in Rathke's pouch appear as tightly packed, columnar cells. When they cease dividing and move to the anterior lobe, their shape becomes round and they are less densely distributed (1). These changes in cell movement are accompanied by dynamic expression of cell adhesion molecules, most notably the cadherins. In rat development at embryonic day (e) 11, E-cadherin protein is expressed throughout the oral ectoderm, whereas N-cadherin is limited to the primordium of Rathke's pouch. At e13, N-cadherin and E-cadherin are both broadly expressed over the entire pituitary cell population, with N-cadherin more prominently lining the lumen of Rathke's pouch. Most cells express both N-cadherin and E-cadherin until mature hormone-producing cells begin to appear (2). Around the time of birth, hormone-producing cells express only N-cadherin, whereas folliculostellate cells and marginal cell layers express E-cadherin (3). Also, N-cadherin mRNA levels are highest at postnatal day (P) 1 and decrease until the animal reaches sexual maturity (4). In the adult mouse, hormone-producing cells are distributed throughout the pituitary, but cells expressing the same hormone organize into networks through cell-cell connections that can be delineated based on the complement of adhesion molecules they express (4, 5).

Although adhesion molecule expression in the developing and adult pituitary has been described, its function in normal pituitary physiology has not been extensively explored. Of particular interest is N-cadherin, a calcium-dependent homophilic cell-cell adhesion molecule that is associated with adherens junctions (6). The cytoplasmic domain of N-cadherin interacts with β-catenin, α-catenin, and p120, providing the mechanism connecting cell surface adhesion to the actin cytoskeleton. N-cadherin is essential for the formation of multiple organ systems in the body, in which it is thought to control cell movement and arrangement. In the adult heart, loss of N-cadherin results in disassembly of the intercalated disc structure because of disorganization of the adherens junctions and desmosomes (7). In the brain, N-cadherin is necessary to produce a cortex with a precise laminar structure. Without N-cadherin, cortical neurons also proliferate excessively, indicating that the adherens junctions can relay an important signal controlling organ size (8). Cadherins can also play a significant role in cell sorting. For instance, in the developing eye, N-cadherin cooperates with E-cadherin to promote separation of the lens vesicle from the overlying ectoderm (9). These studies indicate that N-cadherin is important for the morphology of multiple organ systems in the body by providing structural support through linking to the actin cytoskeleton and providing a mechanism for cell-cell communication in processes such as proliferation.

Although the role of N-cadherin in the initial formation of the pituitary as well as its contribution to homeostatic cell generation is unknown, studies point to a role in controlling tissue morphogenesis and possibly proliferation. During development, Prop1, a pituitary specific homeobox transcription factor in the Notch signaling pathway, is necessary for down-regulating N-cadherin in the cells lining the lumen of Rathke's pouch (1). In the Prop1 mutant, cells that stop dividing remain columnar, retain N-cadherin expression uniformly, and become trapped in Rathke's pouch in which they eventually die (1, 10). N-cadherin, through adhesion mediated cell-cell interactions, may also be involved in the control of adult pituitary cell number, including preventing tumor formation. Pituitary tumors are common in the general population, and although tumors in rodents and humans rarely metastasize, they can become locally invasive. Studies have also shown that reduced expression of N-cadherin in a mouse xenograft model can accelerate tumor progression and increase pituitary tumor invasiveness when fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling, a potent cell mitogen, is also altered (11, 12). Additionally, a loss of N-cadherin in conjunction with ptd-FGF receptor 4 expression has also been found in a subset of human pituitary tumors, with the absence of membrane N-cadherin protein expression correlating with tumor invasiveness (12). It is unclear whether the down-regulation of N-cadherin is sufficient to modulate the proliferation of the tumor cells or their spread into surrounding tissues. Due to these findings, we are interested in how N-cadherin affects the interaction and proliferation of distinct cell lineages of the pituitary.

Because complete loss of N-cadherin function in all murine tissue results in embryonic lethality due to cardiac defects, tissue-specific deletions are necessary to uncover its diverse roles (13). To examine the function of N-cadherin in the pituitary, we created N-cadherin conditional knockouts (cKO) by mating N-cadherin floxed mice to mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Pomc promoter (7, 14). Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is the precursor protein specific to melanotrope and corticotrope cell populations and is cleaved to produce MSH in melanotropes and ACTH in corticotropes. We are interested in cells expressing Pomc because these cells become misplaced when Notch signaling is altered in Prop1, Hes1 double mutants (1). This altered placement correlates with changes in N-cadherin localization.

We hypothesize that the loss of N-cadherin in melanotropes and corticotropes may affect the localization and proliferation of these cells during development when cells are differentiating and migrating. In adulthood N-cadherin may be necessary to modulate proliferation, preventing tumor formation, and to permit newly generated cells to integrate into networks. Our findings demonstrate that N-cadherin is necessary for the spatial organization of POMC-containing cells in the murine anterior lobe. In the areas of N-cadherin loss, α- and β-catenin are also significantly down-regulated, which likely contributes to the changes in morphology that are observed. Surprisingly, markers of cell proliferation are not altered when N-cadherin is lost. Taken together, these data reveal important roles of N-cadherin in pituitary cell interactions that are critical for pituitary organogenesis and homeostasis.

Results

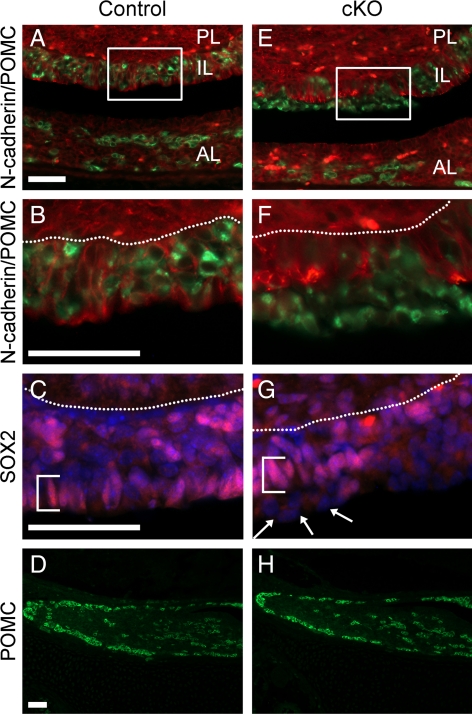

N-cadherin is necessary by P1 to maintain a distinct intermediate lobe boundary

N-cadherin is expressed throughout the murine pituitary from the first day of pituitary formation at e9.5 and continuing on throughout adulthood (2, 3) (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org, and data not shown). To determine the function of N-cadherin in a defined pituitary cell population, Pomc-Cre mice were crossed with N-cadherin floxed mice to generate corticotrope and melanotrope loss of N-cadherin (referred to as cKO). In wild-type mice, Pomc mRNA is detected in the AL corticotropes around e12.5 and in the IL melanotropes around e14.5, with the protein following a day later (15). At P1 in the N-cadherin floxed mice without Pomc-Cre (control), N-cadherin expression appears to be localized to the membrane of most cells of both the AL and IL (Fig. 1A). At this age, POMC-expressing melanotropes comprise the majority of cells located in the IL (Fig. 1, A and B), and POMC-expressing corticotropes are scattered throughout the AL (Fig. 1, A and D). Both populations of cells have N-cadherin expression. However, in the cKO AL and IL, there are patches of cells in which N-cadherin is lost or severely reduced (Fig. 1E and data not shown). Although POMC is still present in the IL (Fig. 1, E and F) and AL (Fig. 1, E and H) of the cKO, POMC and N-cadherin colabeling demonstrates that N-cadherin protein loss strictly correlates with POMC-positive cells. This indicates that N-cadherin was successfully deleted specifically in the POMC cells of the AL and IL. Overall, there does not appear to be any obvious differences in corticotrope cell number or placement between the ALs of the control and cKO animals at P1 (Fig. 1, D and H). However, in the cKO pituitaries, disorganization of the melanotropes in the IL is evident by examining the border of SOX2 immunoreactive progenitor cells along the cleft. In the control, virtually every cell bordering the cleft contains SOX2 (Fig. 1C, bracket), whereas in the cKO, there are cells lacking SOX2 that line the IL border along the cleft (Fig. 1G, arrows). These cells are positive for POMC. Each mutant examined displayed regions of disorganization; however, the severity of the disorganization varies randomly throughout the IL. These data indicate that N-cadherin expression is an important molecule in maintaining IL organization and cell sorting at P1.

Fig. 1.

Disorganization of POMC-expressing cells is evident in the IL but not the AL of the cKO at P1. Pituitaries at P1 were sectioned coronally and examined by immunohistochemistry for N-cadherin and POMC. N-cadherin expression is present throughout the PL, IL, and AL at P1 in the control mouse (A, red). POMC is expressed throughout most of the IL and in scattered cells of the AL (A, green). Higher magnification of the IL reveals all melanotropes contain N-cadherin at their cell membrane (B). In the cKO, N-cadherin is lost in patches of the IL (E and F, red), which correspond with cells expressing POMC (E and F, green). The border of SOX2-containing cells, seen in the control (C, red, bracket), is not consistently maintained in the cKO (G, red) IL, and melanotropes are seen in ectopic positions (arrows). In C and G, nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). In the AL, POMC-expressing cell distribution appears similar in both the control (D) and cKO (H) (n = 6–8, two sections from each animal). PL, Posterior lobe; IL, intermediate lobe; AL, anterior lobe. Magnification, ×200 (A and E), ×400 (B, C, F, and G); ×100 (D and H). Scale bar, 50 μm.

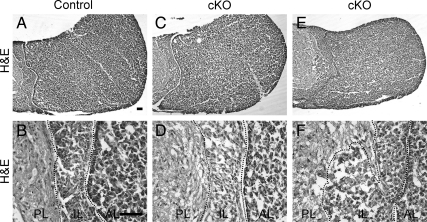

Melanotrope placement is not commonly altered with N-cadherin loss at P30

To determine the effect of sustained N-cadherin loss on melanotropes, cKO mice were examined at P30 and 6 months of age. A control pituitary has all three pituitary lobes: AL, IL, and PL (Fig. 2, A and B). We observed these structures in the proper place in virtually all of the cKO pituitaries (Fig. 2, C and D). However, we did detect an impaired border between the IL and PL in one of the mutants, resulting in large groups of IL cells invading the PL (Fig. 2, E and F). At 6 months of age, the pituitaries of control and cKO mice are similar in appearance to those at P30 (Supplemental Fig. 2), and no tumors formed. Because of these findings, we chose to concentrate on P30 pituitaries for the rest of the analysis.

Fig. 2.

Rare disorganization of the IL is evident at P30 in the cKO. Transversely sectioned pituitaries were stained for morphology with hematoxylin and eosin at P30. In the control pituitary at P30, there are three distinct lobes: PL, IL, and AL (A and B). The morphology of the cKO pituitaries resembled that of the control (C and D), whereas IL cells in one cKO appeared to be invading the PL (E and F) (n = 23–28, four to 12 sections from each individual). Magnification, ×100 (A, C, and E); ×400 (B, D, and F). Scale bar, 50 μm.

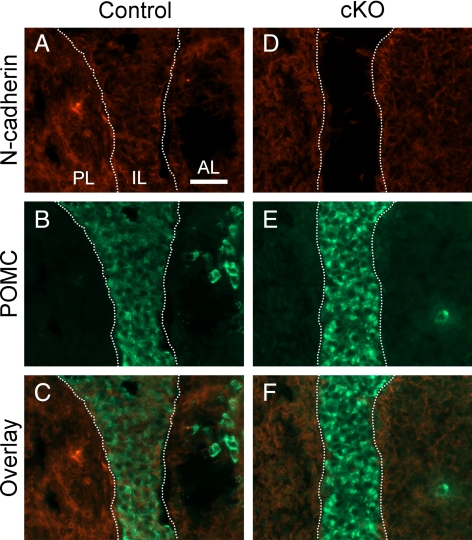

To confirm that the IL cells have lost N-cadherin at P30, we performed a double stain for N-cadherin and POMC. At this age, N-cadherin expression is found in virtually all cells of the control pituitary, including the melanotropes of the IL (Fig. 3A). However, in the cKO, N-cadherin is lost in the IL (Fig. 3D). POMC-immunoreactive melanotropes are present in both the control (Fig. 3B) and cKO (Fig. 3E) ILs, and the overlays demonstrate the absence of N-cadherin in the IL of the cKO (Fig. 3F), compared with control (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data show that N-cadherin loss in the melanotropes does not overtly affect their localization.

Fig. 3.

N-cadherin is lost in the IL cells of the cKO pituitary at P30. Immunohistochemistry for N-cadherin and POMC was performed on transverse sections of pituitaries at P30. N-cadherin expression is present in nearly all cells of the PL, IL, and AL at P30 in the control pituitary (A) but is absent on the majority of the IL cells in the cKO (D). POMC-expressing cells are the predominant cell type in the IL of the control and cKO pituitaries (B and E). In the control, N-cadherin is present in the POMC-expressing cells of the IL (C, overlay). However, in the cKO, it appears that N-cadherin is absent where POMC is expressed (F, overlay) (n = 9–13). Magnification, ×400. Scale bar, 50 μm.

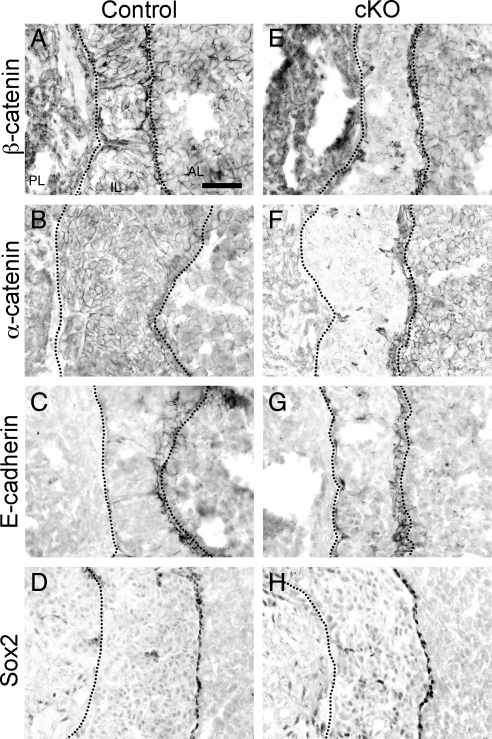

Loss of N-cadherin affects α- and β-catenin expression but not that of E-cadherin or SOX2 in the IL at P30

A prominent role of N-cadherin is to interact with β-catenin, which in turn associates with α-catenin to tether to the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in Refs. 6 and 16). Therefore, we hypothesized that the loss of N-cadherin would lead to a disruption in both α- and β-catenin localization. In the control pituitary, expression of β-catenin mimics that of N-cadherin; it is present along the cell membrane of virtually all cells (Fig. 4A). In the IL, α-catenin is also detectable in all cells (Fig. 4B). In the cKO, we observed a severe reduction in both β-catenin (Fig. 4E) and α-catenin (Fig. 4F) membrane localization that corresponded with the loss of N-cadherin in the IL. This disruption of catenin expression in the cKO confirms that at least one of their roles in the pituitary involves interacting with N-cadherin at the cell membrane.

Fig. 4.

Both β- and α-catenin are lost in the IL in the cKO at P30. Pituitaries were sectioned transversely at P30 and stained via immunohistochemistry for β-catenin, α-catenin, and E-cadherin. The expression of both β- and α-catenin is seen throughout the IL of the control pituitaries (A and B, respectively) in a similar manner to N-cadherin. The β- and α-catenin expression in the cKO appears to be lost in the majority of IL cells (E and F, respectively). Conversely, E-cadherin expression appears to line only the residual cleft of the IL in both the control (C) and cKO (G) pituitaries. SOX2 expression is similarly detected in cells lining the border of the IL and AL in the control (D) and cKO (H) pituitaries (n = 5–7). Magnification, ×400. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Along with N-cadherin, E-cadherin is present in the murine pituitary and also associates with α- and β-catenin. Although E-cadherin is present in the IL, it is found only in the stem-like cells along the cleft, which contain SOX2 but do not express POMC. Similarly, we found that E-cadherin expression in the control pituitary is restricted to a one- or two-cell thick layer lining the cleft that separates the IL from the AL (Fig. 4C) as well as in folliculostellate cells of the AL (data not shown). In the cKO, we saw a nearly identical pattern. E-cadherin expression along the cleft did not appear disrupted despite the loss of N-cadherin and α- and β-catenin throughout nearly all of the IL (Fig. 4G). Additionally, N-cadherin expression was retained along the cleft and overlapped with that of E-cadherin (data not shown). Furthermore, unlike the aberrant border of SOX2-containing cells seen at P1, at P30 SOX2 is detected in a single cell layer of the control (Fig. 4D) and cKO (Fig. 4H) IL-AL border. Therefore, N-cadherin can be retained in cells, even when the neighboring cells have lost N-cadherin expression and although loss of N-cadherin in the melanotropes diminishes many markers of adherens junctions, the cells remain properly localized to the IL.

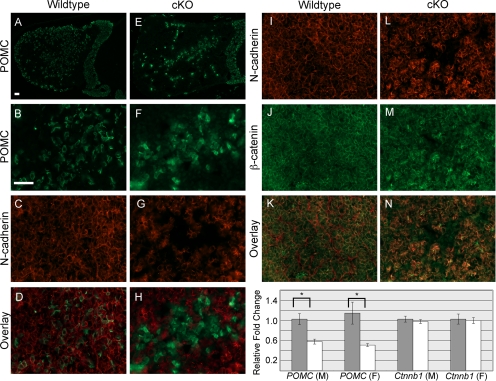

Corticotrope cell distribution is disrupted at P30 when N-cadherin is lost

Corticotropes in the AL also contain N-cadherin, but its function in these cells that are dispersed throughout the gland is unknown. We did not notice any differences in POMC expression or corticotrope distribution between the control and cKO AL at P1 (Fig. 1). At P30 in control animals, corticotropes are dispersed throughout the AL, with a concentration at the periphery of the gland (Fig. 5, A and B). However, in the cKO, we observed an irregular clustering of POMC-positive cells in the center of the AL as well as a partial loss of positive cells at the periphery (Fig. 5, E and F). Also striking is the difference in the POMC expression pattern in individual corticotrope cells. When control pituitaries are stained with the POMC antibody, POMC is localized to the cytoplasm producing a crisp, ringing pattern surrounding the nucleus and allowing individual cells to be easily visualized (Fig. 5B). However, cKO pituitaries appear to have hazy POMC immunoreactivity that does not appear to be confined to the cytoplasm, making it difficult to distinguish the individual POMC-positive cells from the negative ones (Fig. 5F). These changes in POMC cell distribution, and potentially number, are accompanied by a reduction in Pomc mRNA in both males and females (Fig. 5O). To confirm that N-cadherin is indeed lost in the corticotropes and is unaffected in neighboring cells, we double stained for POMC and N-cadherin in both the control (Fig. 5C) and cKO (Fig. 5G). Normally, N-cadherin and POMC are coexpressed (Fig. 5D). However, as expected, we observed a loss of N-cadherin in the POMC-expressing cells of the cKO (Fig. 5H). This suggests that although N-cadherin is dispensable for the initial placement and specification of corticotropes, it is necessary for the proper distribution of the corticotropes during early adulthood. Surprisingly, even though the corticotropes appear disrupted when N-cadherin is lost, morphology of the adrenal gland, an organ that relies on proper release of ACTH for its morphogenesis, is not overtly affected in males and females (Supplemental Fig. 3). The effect of N-cadherin loss in the anterior lobe is cell autonomous because other hormone-producing cell types are still evenly distributed throughout the gland and do not seem to be altered in number (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

The AL of the cKO pituitary has misplaced POMC-expressing cells and lower levels of Pomc mRNA. In the AL of a control pituitary at P30, POMC-expressing cells are detected by immunohistochemistry and appear scattered throughout the lobe (A and B). N-cadherin is present in virtually all of the cells of the control AL (C), including the POMC-expressing cells (D, overlay). However, in the AL of the cKO pituitary, POMC-expressing cells appear to be irregularly organized into clusters (E and F), and N-cadherin expression (G) does not overlap with POMC (H, overlay). β-Catenin expression (J) in the anterior lobe of the control pituitary has a similar pattern to N-cadherin (I) in that it rings nearly all of the cells (K, overlay). However, in the cKO, it appears that β-catenin expression (M) is altered where N-cadherin (L) is absent (N, overlay). When mRNA levels of β-catenin (Ctnnb1) were measured by quantitative RT-PCR, there was no difference between the control (gray bars) and cKO (white bars) levels in either the male (M) or female (F) ALs (O). However, Pomc mRNA levels were significantly decreased between the control (gray bars) and cKO (white bars) in the anterior lobes of both the males and females (O, bracket and asterisks) [P < 0.008 for males and P < 0.03 for females; n = 3–10 (immunohistochemistry); n = 3–7 (quantitative RT-PCR)]. Magnification, ×100x (A and E); ×400x (B–D and F–N). Scale bar, 50 μm.

β-Catenin loss mirrors that of N-cadherin in the AL at P30

Because β-catenin is important for N-cadherin function and it was disrupted in the IL of the cKO at P30, we examined its expression in the AL. As previously mentioned, N-cadherin is localized to the membrane of virtually every cell of the AL in the control pituitary (Fig. 5I) and is lost in POMC-expressing cells in the cKO (Fig. 5L). Like N-cadherin, β-catenin can also be found ringing nearly every cell in the control AL (Fig. 5J). In the same cells in which N-cadherin is lost in the AL of the cKO, β-catenin expression no longer displays prominent membrane staining (Fig. 5M). Overlay of the N-cadherin and β-catenin staining confirms that the β-catenin expression pattern mirrors that of N-cadherin in both the control (Fig. 5K) and the cKO (Fig. 5N). This loss of membrane β-catenin staining likely represents a change in protein distribution or protein levels and not a change in transcription because Ctnnb1 mRNA is unaltered in both male and female cKO ALs (Fig. 5O). Therefore, loss of N-cadherin results in a disruption of the expression of β-catenin in not only the IL of the pituitary but the AL as well.

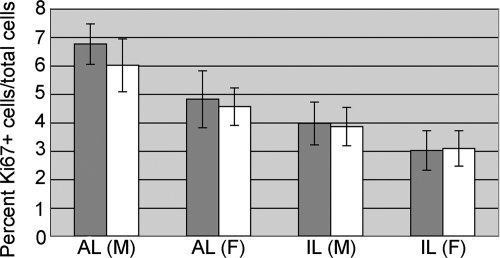

Proliferation is unaffected by loss of N-cadherin

N-cadherin is known to regulate cell number, and its expression is lost in a subset of pituitary tumors (12). We reasoned that loss of N-cadherin may affect proliferation in the melanotropes or corticotropes and may lead to tumor formation. In the control P30 pituitary, proliferating cells marked by Ki67 were quantified in both the AL and IL of male and female pituitaries. When the ratio of Ki67 positive cells to total cell counts is compared between the control and the cKO, no change in proliferation is observed (Fig. 6). These data, combined with the fact that tumors were not formed in the cKO pituitaries up to 6 months of age (Supplemental Fig. 2), indicate that loss of N-cadherin is not sufficient to change cell division activity or initiate tumor formation.

Fig. 6.

AL proliferation is unaffected by loss of N-cadherin at P30. Cell counting was performed on sections of ALs of both control and cKO pituitaries at P30 that were stained by immunohistochemistry for Ki67. There was no significant difference in the percent of Ki67+ cells between the control (gray bars) and cKO (white bars) in the male (M) or female (F) AL or IL [n = 5 (control male and female), n = 6 (cKO male), n = 9 (cKO female)].

Discussion

Adhesion is essential for the organization of cells into organs. Although dynamic changes in adhesion happen during embryonic development, there is also a need for sustained adhesion in adult tissue, possibly to support tissue remodeling or intercellular signaling. N-cadherin, a member of the classic cadherin family, is a homophilic cell adhesion molecule that mediates cell-cell interactions that are necessary for adhesion, cell sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. In the pituitary, N-cadherin is expressed from the earliest stages of development in all cells. There is a dynamic redistribution of N-cadherin from the membranes of cells that have exited the cell cycle and are in the process of moving to the anterior lobe in which they will differentiate. In the adult, N-cadherin is present on the membranes of all hormone-producing cells, but there is evidence to suggest that expression levels may vary, depending on cell type (4).

By using a conditional deletion strategy, we found that N-cadherin expression in melanotropes and corticotropes is necessary to sustain the expression of other adherens junction proteins in a cell-autonomous manner. Specifically, β-catenin membrane expression drops dramatically in both cell types without N-cadherin. A less pronounced reduction in β-catenin also occurs in the cardiac outflow tract when N-cadherin is conditionally deleted (17). In contrast, β-catenin remains localized to synapses of N-cadherin cKO cortices (8). These data demonstrate that β-catenin can be regulated by N-cadherin, but, in some cases, other factors may act redundantly to sustain its expression when N-cadherin is lost. In the pituitary, N-cadherin appears to be one of the major regulators of β-catenin levels. β-Catenin can serve two very important roles in the cell: a structural scaffold linking N-cadherin to α-catenin and the actin cytoskeleton and also as a critical component of the Wnt signaling pathway. Although we saw no change at the mRNA level, β-catenin protein staining was diminished. With the change in β-catenin protein distribution, there may be a reduction in Wnt signaling in the corticotropes and melanotropes of the cKO. Wnt signaling is known to be active in the developing pituitary, in which it plays a role in pituitary shape (18–21). Yet conditional deletion of β-catenin in the Pit1 lineage (thyrotropes, somatotropes, and lactotropes) had no effect on cell specification or placement. However, these mice were examined only until the day of birth (22). Although a corticotrope deletion of β-catenin has not been explored, we may expect to find a similar phenotype to the N-cadherin deletion at P30 or no effect if another molecule like plakoglobin compensates for β-catenin loss, as it does in other systems (23).

The main consequence of loss of N-cadherin and the accompanying proteins α- and β-catenin is mislocalization of the corticotropes. Based on this observation, it is likely that one main role of N-cadherin mediated cell-cell interactions is to facilitate cell sorting. During embryogenesis, differentiated cells first appear in the pituitary in distinct locations. In the adult, however, the hormone cells become interspersed throughout the anterior lobe. We found that the initial specification and placement of corticotropes is unaffected by loss of N-cadherin. This may indicate that the first wave of corticotropes that populate the gland do not need to interact with each other through N-cadherin. There may be another redundant adhesion system in place, or less likely, the embryonic pituitary cells do not rely on adhesion molecules for their placement. In contrast, during the proliferative expansion of the pituitary that occurs postnatally, N-cadherin is critical for directing the corticotropes to distributed positions throughout the gland. Previous work has shown that in both humans and mice, corticotrope cell density is not uniform (24, 25). Our data demonstrate that the placement of corticotrope cells in the AL is, in fact, very precise and that N-cadherin is a critical mediator. Although N-cadherin is important in cell distribution in postnatal mice, it is likely not the only molecule playing a role. Pituitary cells also have other adhesion molecules that may permit them to recognize cells they need to communicate and associate with such as neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) and other cadherins (4, 26).

The role of cell dispersal in the pituitary is incompletely understood. Studies have elucidated that pituitary cells can form long-range networks that are linked by adherens junctions containing N-cadherin and β-catenin (4, 5, 27). It is thought that the somatotrope networks allow for the coordinated, pulsatile release of GH in response to stimulation (28). N-Cadherin may play a critical role in establishing and regulating these networks because N-cadherin stimulation in vitro results in GH secretion from fetal and tumor cultures (29). Furthermore, N-cadherin expression in somatotropes is dynamically regulated by estrogen and FGF receptor 4 signaling (11, 12, 30, 31), providing a mechanism by which cell-cell communication can be altered in response to the environment. Although the presence of corticotrope networks has not been formally explored, the expression and function of similar adherens junction proteins in these cells makes it plausible. It is unclear whether the communication between corticotropes has been altered due to loss of N-cadherin. There is a precedent for loss of cell adhesion to cause changes in hormone secretion. In the pancreas of N-cadherin tissue-specific knockouts, the number of mature insulin secretory granules is altered. In conditions of low glucose, there was a reduction in insulin secretion, although in response to high glucose, the difference was not statistically significant (32). However, loss of the adhesion molecule N-CAM within the pancreas leads to defects in hormone release of greater severity (33), indicating there may be some redundancy in the cell adhesion machinery that modulates hormone release. We did see a change in the subcellular distribution of ACTH in corticotropes lacking N-cadherin, yet the adrenal glands still formed appropriately. Because ACTH is essential for adrenal gland morphogenesis, this indicates that ACTH can be released at a level from the cKO pituitary sufficient to exert a biological effect (34–36). Even though corticotropes are not in the correct position and ACTH localization appears abnormal, they can still function in the absence of N-cadherin. Possibly another molecule such as N-CAM is still providing a redundant intercellular communication cue as N-cadherin.

In contrast to the dispersed nature of the anterior lobe cells, melanotropes are the sole hormone-producing cell type that we know of in the intermediate lobe of the mouse. Our studies show that N-cadherin is mostly dispensable for melanotropes to remain within the IL. However, we did detect melanotropes in the posterior lobe of one cKO, something never seen in control pituitaries. The posterior lobe is neural in origin and contains pituicytes and axon terminals of magnocellular neurons, whereas the IL and AL are derived from Rathke's pouch. In humans there is only a rudimentary IL; however, the phenomenon of basophil invasion, a movement of ACTH-immunoreactive cells from the residual IL to the posterior lobe, occurs in about 5% of the population (37, 38). The mechanism for this invasion is unknown, but our results suggest that changes in N-cadherin in intermediate lobe melanotropes is permissive for posterior lobe invasion but would likely need to be combined with another genetic or environmental alteration.

Pituitary tumors are common in the human population, and the murine IL is also prone to tumors. Although loss of the cell cycle regulators Rb and p27 lead to pituitary tumor formation in the IL (39–41), loss of N-cadherin did not result in excess cell division of melanotropes or corticotropes. This finding was somewhat surprising because somatotrope tumor GH4 cells form more aggressive and invasive tumors in a xenograft model when N-cadherin expression is reduced by small interfering RNA (12). Our data demonstrate that loss of N-cadherin alone is not sufficient to induce tumor formation in corticotropes or melanotropes by 6 months of age in the mouse. It is possible that tumors may form beyond the time at which we examined, but it is also likely that another hit, such as altered signaling, is necessary to stimulate proliferation. However, N-cadherin and β-catenin expression certainly modulates cell placement and possibly prevents tumors from becoming invasive. In fact, expression of N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and β-catenin has been shown to be significantly lower in invasive compared with noninvasive human pituitary tumor cells (12, 42). Although our data do not exclude, or point to, N-cadherin as a critical molecule directing tumor formation, it is possible that in humans N-cadherin plays a distinct role from mice. Taken together, our studies highlight the importance of sustained N-cadherin expression in pituitary cell organization.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice with loxP sites flanking exon 1 of the N-cadherin (Cdh2) gene were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and used to establish a breeding colony (7). The progeny from this colony were bred to Pomc-Cre mice, also purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (14). Pomc-Cre transgenic mice were created by homologous recombination of Cre encoding DNA sequence into a bacterial artificial chromosome containing 45 kb 5′ and 70 kb 3′ of Pomc sequence. Insertion of Cre occurred at the start codon of Pomc and deleted the first 30 bp of the Pomc gene in this bacterial artificial chromosome. Subsequent matings involved breeding N-cadherin fl/fl males to N-cadherin fl/fl Pomc-Cre females to produce both control (N-cadherin fl/fl) and cKO (N-cadherin fl/fl Pomc-Cre) mice. All mice were provided with 6% rodent chow and water ad libitum. All procedures involving mice were approved by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

To genotype the mice, DNA from tail biopsies was isolated using a DNA salt-out technique followed by PCR. The PCR reaction mixture contained 1.56 mm MgCl2, 1 U Go Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), 12.5 pmol of each primer, 1× Promega 5X Green GoTaq Flexi Buffer, 10 mm of deoxynucleotide triphosphate mix, and 1 μl of DNA per reaction. The following primers were used to detect the N-cadherin floxed allele: 5′-TGC TGG TAG CAT TCC TAT GG-3′ and 5′-TAC AAG TTT GGG TGA CAA GC-3′ (7). The samples underwent 35 cycles of denaturing at 95 C for 30 sec, annealing at 55 C for 30 sec, and elongation at 72 C for 30 sec, followed by 72 C for 10 min. The following primers were used to detect the Pomc and Cre alleles: 5′-TGG CTC AAT GTC CTT CCT GG-3′, 5′-CAC ATA AGC TGC ATC GTT AAG-3′, and 5′-GAG ATA TCT TTA ACC CTG ATC-3′. The samples underwent 35 cycles of denaturing at 95 C for 30 sec, annealing at 55 C for 30 sec, and elongation at 72 C for 1 min, followed by 72 C for 10 min.

Immunohistochemistry

The mice were killed at e16.5, P1, P30, or 6 months of age and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde diluted in PBS (pH 7.2). For paraffin embedding (e16.5, P1, and P30), the samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol before being embedded in paraffin and sectioned coronally at 6 μm. The sections were mounted onto charged slides and prepared for the staining procedures. For frozen sectioning (P30 and 6 months), pituitaries were placed in 30% sucrose diluted in PBS overnight, embedded in OCT medium, snap frozen at −80 C and sectioned at 10 μm. A hematoxylin and eosin stain was used to observe cell morphology. To prepare paraffin slides for immunofluorescence, the slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in ethanol and PBS followed by a 10-min boil in 10 mm citric acid (pH 6). The frozen slides were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min, rinsed in PBS, and put in hot citrate for 5 min. All slides were then incubated in the normal donkey serum [5% (wt/vol)] diluted in immunohistochemistry block, which consists of PBS, BSA (3%), and Triton X-100 (0.5%), followed by overnight incubation at 4 C with a primary antibody diluted in immunohistochemistry block against the desired peptide: N-cadherin (1:200; Zymed, San Francisco, CA), ACTH (1:200; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), α-E-catenin (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), β-catenin (1:150; Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA), or E-cadherin (1:150; Cell Signaling). An antimouse secondary antibody conjugated to biotin was used with N-cadherin, whereas antirabbit secondary antibody conjugated to biotin was used with ACTH, α-E-catenin, β-catenin, and E-cadherin. Colabeling required antirabbit, antirat, or antimouse directly conjugated to the fluorophore. Either Strep-Dylight 488 or Strep-CY3 for signal detection was used followed by mounting with an aqueous mounting medium. All secondary and strep-conjugated antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

After staining as described above, images of the slides were viewed at ×400 and ×200 magnification with a Leica DM2500 microscope (Heidelberg, Germany), captured with the Retiga 2000R color camera (Q-Imaging, Surrey, Canada) attached to the microscope, and the pictures were acquired in Q-Capture Pro (Q-Imaging). Images were processed in Adobe Photoshop CS2 (San Jose, CA).

Proliferation quantification

The quantification of proliferation was performed at P30 in control and cKO samples (n ≥ 5). All pituitaries were oriented the same way and a ×400 picture was taken in the center of each AL and along either of the lateral sides of the IL. Using the ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), the total number of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)+ cells in each of the ×400 pictures was counted (only the DAPI+ cells within the IL were counted for the IL values). The total number of Ki67+ cells within the picture (AL) or IL were counted. For the AL values, the two lobe values were averaged for each sample. The number of KI67+ cells was divided by the number of DAPI+ cells to determine the percentage of proliferating cells within the field of view for each sample. The data were analyzed with a t test performed by the SAS program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to determine significance, sd, and se.

RNA analysis

An RNAqueos-micro kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used to isolate RNA from individually isolated P30 ALs according to the manufacturer's protocol. After deoxyribonuclease treatment (Ambion), 0.5 μg RNA was converted into cDNA with the ProtoScript cDNA synthesis kit and random hexamers (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were also processed through the cDNA synthesis in the absence of enzyme to serve as a negative control (−RT). Then 0.2 μl cDNA was amplified with gene-specific primers and SYBR green (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) on a Bio-Rad MyIQ real-time PCR machine. Data were analyzed with the change in cycle threshold (ΔCt) value method and statistical significance determined by a Student's t test.

Primers for RT-PCR include: Gapdh forward, GGTGAGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATG; Gapdh reverse, GACCCGTTTGGCTCCACCCTTC; Ctnnb1 forward, CACGCAGTGAAGAATGCACACG; Ctnnb1 reverse, AGCAAGGCTAGGGTTTGATAACGC; Pomc forward, GTTACGGTGGCTTCATGACCTC; Pomc reverse, CGCGTTCTTGATGATGGCGTTC.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Katherine Brannick (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL) for assistance with mouse breeding. We also thank Paven Aujla, Tyler Moran, and other members of the Raetzman Lab (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01DK076647 (to L.T.R.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AL

- Anterior lobe

- cKO

- N-cadherin conditional knockout

- DAPI

- 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- e

- embryonic day

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- IL

- intermediate lobe

- N-CAM

- neural cell adhesion molecule

- P

- postnatal day

- PL

- posterior lobe

- POMC

- proopiomelanocortin.

References

- 1. Himes AD, Raetzman LT. 2009. Premature differentiation and aberrant movement of pituitary cells lacking both Hes1 and Prop1. Dev Biol 325:151–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kikuchi M, Yatabe M, Kouki T, Fujiwara K, Takigami S, Sakamoto A, Yashiro T. 2007. Changes in E- and N-cadherin expression in developing rat adenohypophysis. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 290:486–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kikuchi M, Yatabe M, Fujiwara K, Takigami S, Sakamoto A, Soji T, Yashiro T. 2006. Distinctive localization of N- and E-cadherins in rat anterior pituitary gland. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 288:1183–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chauvet N, El-Yandouzi T, Mathieu MN, Schlernitzauer A, Galibert E, Lafont C, Le Tissier P, Robinson IC, Mollard P, Coutry N. 2009. Characterization of adherens junction protein expression and localization in pituitary cell networks. J Endocrinol 202:375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonnefont X, Lacampagne A, Sanchez-Hormigo A, Fino E, Creff A, Mathieu MN, Smallwood S, Carmignac D, Fontanaud P, Travo P, Alonso G, Courtois-Coutry N, Pincus SM, Robinson IC, Mollard P. 2005. Revealing the large-scale network organization of growth hormone-secreting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:16880–16885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gumbiner BM. 2005. Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:622–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kostetskii I, Li J, Xiong Y, Zhou R, Ferrari VA, Patel VV, Molkentin JD, Radice GL. 2005. Induced deletion of the N-cadherin gene in the heart leads to dissolution of the intercalated disc structure. Circ Res 96:346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kadowaki M, Nakamura S, Machon O, Krauss S, Radice GL, Takeichi M. 2007. N-cadherin mediates cortical organization in the mouse brain. Dev Biol 304:22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pontoriero GF, Smith AN, Miller LA, Radice GL, West-Mays JA, Lang RA. 2009. Co-operative roles for E-cadherin and N-cadherin during lens vesicle separation and lens epithelial cell survival. Dev Biol 326:403–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ward RD, Raetzman LT, Suh H, Stone BM, Nasonkin IO, Camper SA. 2005. Role of PROP1 in pituitary gland growth. Mol Endocrinol 19:698–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ezzat S, Zheng L, Asa SL. 2004. Pituitary tumor-derived fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 isoform disrupts neural cell-adhesion molecule/N-cadherin signaling to diminish cell adhesiveness: a mechanism underlying pituitary neoplasia. Mol Endocrinol 18:2543–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ezzat S, Zheng L, Winer D, Asa SL. 2006. Targeting N-cadherin through fibroblast growth factor receptor-4: distinct pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. Mol Endocrinol 20:2965–2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Radice GL, Rayburn H, Matsunami H, Knudsen KA, Takeichi M, Hynes RO. 1997. Developmental defects in mouse embryos lacking N-cadherin. Dev Biol 181:64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC, Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. 2004. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron 42:983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Japón MA, Rubinstein M, Low MJ. 1994. In situ hybridization analysis of anterior pituitary hormone gene expression during fetal mouse development. J Histochem Cytochem 42:1117–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodwin M, Yap AS. 2004. Classical cadherin adhesion molecules: coordinating cell adhesion, signaling and the cytoskeleton. J Mol Histol 35:839–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luo Y, High FA, Epstein JA, Radice GL. 2006. N-cadherin is required for neural crest remodeling of the cardiac outflow tract. Dev Biol 299:517–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Potok MA, Cha KB, Hunt A, Brinkmeier ML, Leitges M, Kispert A, Camper SA. 2008. WNT signaling affects gene expression in the ventral diencephalon and pituitary gland growth. Dev Dyn 237:1006–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brinkmeier ML, Potok MA, Davis SW, Camper SA. 2007. TCF4 deficiency expands ventral diencephalon signaling and increases induction of pituitary progenitors. Dev Biol 311:396–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cha KB, Douglas KR, Potok MA, Liang H, Jones SN, Camper SA. 2004. WNT5A signaling affects pituitary gland shape. Mech Dev 121:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brinkmeier ML, Potok MA, Cha KB, Gridley T, Stifani S, Meeldijk J, Clevers H, Camper SA. 2003. TCF and Groucho-related genes influence pituitary growth and development. Mol Endocrinol 17:2152–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olson LE, Tollkuhn J, Scafoglio C, Krones A, Zhang J, Ohgi KA, Wu W, Taketo MM, Kemler R, Grosschedl R, Rose D, Li X, Rosenfeld MG. 2006. Homeodomain-mediated β-catenin-dependent switching events dictate cell-lineage determination. Cell 125:593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fukunaga Y, Liu H, Shimizu M, Komiya S, Kawasuji M, Nagafuchi A. 2005. Defining the roles of β-catenin and plakoglobin in cell-cell adhesion: isolation of β-catenin/plakoglobin-deficient F9 cells. Cell Struct Funct 30:25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baker BL, Gross DS. 1978. Cytology and distribution of secretory cell types in the mouse hypophysis as demonstrated with immunocytochemistry. Am J Anat 153:193–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trouillas J, Guigard MP, Fonlupt P, Souchier C, Girod C. 1996. Mapping of corticotropic cells in the normal human pituitary. J Histochem Cytochem 44:473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berardi M, Hindelang C, Laurent-Huck FM, Langley K, Rougon G, Félix JM, Stoeckel ME. 1995. Expression of neural cell adhesion molecules, NCAMs, and their polysialylated forms, PSA-NCAMs, in the developing rat pituitary gland. Cell Tissue Res 280:463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Horvath E, Kovacs K, Penz G, Ezrin C. 1974. Origin, possible function and fate of “follicular cells” in the anterior lobe of the human pituitary. Am J Pathol 77:199–212 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lafont C, Desarménien MG, Cassou M, Molino F, Lecoq J, Hodson D, Lacampagne A, Mennessier G, El Yandouzi T, Carmignac D, Fontanaud P, Christian H, Coutry N, Fernandez-Fuente M, Charpak S, Le Tissier P, Robinson IC, Mollard P. 2010. Cellular in vivo imaging reveals coordinated regulation of pituitary microcirculation and GH cell network function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4465–4470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rubinek T, Yu R, Hadani M, Barkai G, Nass D, Melmed S, Shimon I. 2003. The cell adhesion molecules N-cadherin and neural cell adhesion molecule regulate human growth hormone: a novel mechanism for regulating pituitary hormone secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3724–3730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heinrich CA, Lail-Trecker MR, Peluso JJ, White BA. 1999. Negative regulation of N-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by the estrogen receptor signaling pathway in rat pituitary GH3 cells. Endocrine 10:67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith PM, Heinrich CA, Pappas S, Peluso JJ, Cowan A, White BA. 2002. Reciprocal regulation by estradiol 17-β of ezrin and cadherin-catenin complexes in pituitary GH3 cells. Endocrine 17:219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johansson JK, Voss U, Kesavan G, Kostetskii I, Wierup N, Radice GL, Semb H. 2010. N-cadherin is dispensable for pancreas development but required for β-cell granule turnover. Genesis 48:374–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Olofsson CS, Håkansson J, Salehi A, Bengtsson M, Galvanovskis J, Partridge C, SörhedeWinzell M, Xian X, Eliasson L, Lundquist I, Semb H, Rorsman P. 2009. Impaired insulin exocytosis in neural cell adhesion molecule−/− mice due to defective reorganization of the submembrane F-actin network. Endocrinology 150:3067–3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yaswen L, Diehl N, Brennan MB, Hochgeschwender U. 1999. Obesity in the mouse model of pro-opiomelanocortin deficiency responds to peripheral melanocortin. Nat Med 5:1066–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smart JL, Low MJ. 2003. Lack of proopiomelanocortin peptides results in obesity and defective adrenal function but normal melanocyte pigmentation in the murine C57BL/6 genetic background. Ann NY Acad Sci 994:202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smart JL, Tolle V, Otero-Corchon V, Low MJ. 2007. Central dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuron-specific proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice. Endocrinology 148:647–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuebber S, Ropte S, Hori A. 1990. Proliferation of adenohypophyseal cells into posterior lobe. Their normal anatomical condition and possible neoplastic potentiality. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 104:21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fan X, Olson SJ, Johnson MD. 2001. Immunohistochemical localization and comparison of carboxypeptidases D, E, and Z, α-MSH, ACTH, and MIB-1 between human anterior and corticotroph cell “basophil invasion” of the posterior pituitary. J Histochem Cytochem 49:783–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu N, Gutsmann A, Herbert DC, Bradley A, Lee WH, Lee EY. 1994. Heterozygous Rb-1 Δ20/+mice are predisposed to tumors of the pituitary gland with a nearly complete penetrance. Oncogene 9:1021–1027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fero ML, Rivkin M, Tasch M, Porter P, Carow CE, Firpo E, Polyak K, Tsai LH, Broudy V, Perlmutter RM, Kaushansky K, Roberts JM. 1996. A syndrome of multiorgan hyperplasia with features of gigantism, tumorigenesis, and female sterility in p27(Kip1)-deficient mice. Cell 85:733–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kiyokawa H, Kineman RD, Manova-Todorova KO, Soares VC, Hoffman ES, Ono M, Khanam D, Hayday AC, Frohman LA, Koff A. 1996. Enhanced growth of mice lacking the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor function of p27(Kip1). Cell 85:721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Qian ZR, Li CC, Yamasaki H, Mizusawa N, Yoshimoto K, Yamada S, Tashiro T, Horiguchi H, Wakatsuki S, Hirokawa M, Sano T. 2002. Role of E-cadherin, α-, β-, and γ-catenins, and p120 (cell adhesion molecules) in prolactinoma behavior. Mod Pathol 15:1357–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]