Lysine methylation of the androgen receptor by Set9, which is a lysine-specific methyltransferase, enhances the receptor's N-C interaction and transcriptional activity in prostate cancer cells.

Abstract

Lysine methyltransferases modulate activities of transcription factors and transcription coregulators by methylating specific lysine residue(s). We report that the androgen receptor (AR) is methylated at lysine-630 by Set9, which was originally identified as a histone H3K4 monomethyltransferase. Alanine substitution of lysine-630 prevented AR methylation in vitro and in vivo. Set9 methylated the nuclear and cytoplasmic AR utilizing the cofactor S-adenosyl-methionine. A pan-methyllysine antibody recognized endogenous AR, and Set9 coimmunoprecipitated with nuclear and cytoplasmic AR. Set9 overexpression potentiated AR-mediated transactivation of the probasin promoter, whereas Set9 depletion inhibited AR activity and target gene expression. Similar to AR, chromatin occupancy of Set9 at androgen response elements (AREs) was androgen dependent, and associated with methylated histone H3K4 chromatin activation marks and p300/CBP associated factor acetyltransferase recruitment. Set9 depletion increased the histone H3K9-dimethyl repressive mark at AREs and reduced histone activation marks and occupancy of p300/CBP associated factor. K630A mutation reduced amino- and carboxy-terminal (N-C) interaction in Set9-intact cells, whereas N-C interaction for wild-type AR was reduced upon Set9 depletion. The K630A mutant was resistant to loss of activity from Set9 silencing and to increase of activity from Set9 overexpression. The K630 dependence of Set9-regulated N-C interaction and AR activity suggests that Set9 directly acts on AR at the amino acid level. Chromatin recruitment of Set9 to AREs is suggestive of its additional role as a transcriptional coactivator. Because the cellular metabolic state determines the level of S-adenosylmethionine and consequently the activity of Set9, the enhanced activity of methylated AR may have special significance in certain metabolic contexts.

Protein methylation is often an important modulator of mammalian gene expression. Histone methyltransferases were initially characterized for activity on specific lysine or arginine residues of H3 and H4 histone tails and for roles in the modification of local chromatin structure, which results in altered gene activity. Later studies established that many of these enzymes also target nonhistone protein substrates, notably transcription factors and transcription coregulators. For example, the H3 lysine-4 methyltransferase Set9, containing the conserved SET motif of the Drosophila proteins Su(var)3–9, Ez, and Trx, catalyzes methyl group transfer to a single lysine residue of the tumor suppressor protein p53. Methylated p53 is more stable, displays greater nuclear retention, and shows enhanced transcription-regulatory activity (1). Set9-mediated methylation of TAF10 and TAF7, which are TATA box-binding protein-associated factors (TAFs), has been demonstrated, and methylated TAF10 has been shown to confer transcription stimulation in a promoter-specific manner (2). p/CAF, a global transcription coactivator and an acetyltransferase, is methylated by Set9 at multiple lysine residues, although the functional consequence of this covalent modification is unclear (3). Nuclear receptor-directed coactivator assembly/disassembly can depend on coactivator methylation/demethylation (4). Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase methylates the p160 coactivator steroid receptor coactivator 3 to a less stable form that showed reduced interaction with the global coactivator CREB-binding protein, which in turn led to disruption of estrogen receptor-α-associated coactivator assembly at targeted promoters and resulted in the termination of estrogen-induced signaling (5, 6).

Functional responses of the androgen receptor (AR) to posttranslational modifications due to phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation have been extensively examined (7, 8). Acetylation of AR at three lysine residues within a conserved motif in the hinge domain enhanced the androgen-induced transcriptional activity of the receptor (9), whereas two lysine-specific SUMO-1 conjugation sites at the amino-terminal domain have been linked to a context-dependent attenuation of the receptor activity (10). Acetylation alters certain androgen-independent AR functions as well, such as TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis, binding to the histone deacetylase 1, and induction of the cell cycle genes for cyclin D1 and cyclin E (8). Phosphorylation of AR at multiple sites by various kinases also enhanced AR-mediated transactivation (11). Interdependence of acetylation and phosphorylation in the regulation of AR activity, and that of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation in the regulation of AR stability, has been reported (12, 13).

The present study provides evidence that Set9 catalyzes methylation of AR at the hinge domain lysine-630 residue (K630) and that intracellular AR can exist in a methylated state. Set9 enhanced AR transcriptional activity in multiple cell lines originating from the kidney and prostate. The ligand-induced interdomain AR amino- and carboxyl-terminal (N-C) interaction declined markedly in Set9-silenced cells. Furthermore, this interaction was significantly weakened for the mutant AR carrying an alanine substitution for lysine-630 (K630A), which rendered the receptor refractive to Set9-mediated methylation. Unlike the wild-type AR, the K630A receptor was resistant to loss of transcriptional activity in Set9-depleted cells. The K630 methylation site overlaps with one of the three AR acetylation sites (9), and K630T somatic mutation of AR has been identified in prostate cancer (14). Considering that the availability of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), an essential cofactor for Set9 activity, is influenced by cellular metabolic and nutritional states, our results suggest that the K630 residue is an important determinant of AR function in normal physiology and in pathophysiology.

Results

Methylation of the AR hinge domain by Set9

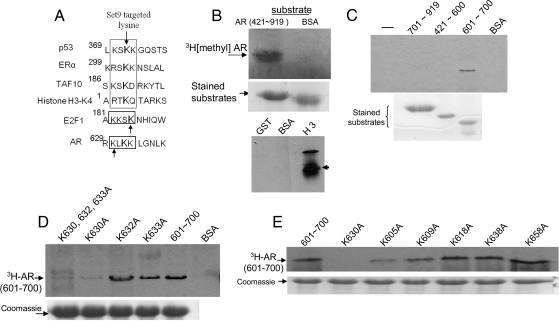

The sequence 629RKLKK633 within the hinge domain of AR (Fig. 1A) has partial similarity to the core Set9-targeted motif (K/R)(S/T)K* (K* = targeted lysine) in known Set9 substrates (such as histone H3, p53, TAF10, and estrogen receptor-α). The recently identified Set9-dependent methylation site in E2F1 (KKSK*) also conforms to this core substrate motif for Set9 (15). Figure 1B shows that recombinant Set9 [prepared as a glutathione-S transferase (GST)-fused enzyme] catalyzed the transfer of [3H]methyl from the cofactor SAM to a truncated human AR fragment [amino acids (AAs) 421-919] covering DNA- and ligand-binding domains of the receptor (Fig. 1B, top panel). Recombinant Set9 strongly methylated histone H3, but not BSA or GST (Fig. 1B, bottom panel). Methylation assay of a series of truncated AR fragments (as GST fusions) showed that the target residue(s) for methylation is (are) located within an AR region spanning AAs 601-700 (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Methylation of AR in vitro and identification of the lysine methylation site. A, Lysine-targeted Set9 motifs of known Set9 substrates and a putative Set9 motif for AR. B, Methylation of GST-AR (AAs 421-919) in an in vitro reaction. B (upper panel), GST-Set9 (3 μg) was incubated with the GST-fused AR fragment in the presence of [3H-methyl]-SAM. 3H signal of methylated AR in the reaction mixture (pH 8.5) was detected by 10% SDS-PAGE and fluorography. BSA lacked Set9 activity. B (middle panel), Coomassie blue staining of GST-AR and BSA. B (bottom panel), The strong histone methyltransferase activity of our GST-Set9 preparation, indicated by methylation of recombinant histone H3. GST and BSA were negative control substrates. C, Methylation of various GST fused AR fragments (upper panel) and Coomassie blue staining of the substrates (lower panel). D and E, Mapping of the AR methylation site. Each number indicates the altered lysine residue (K→A) within the GST-fused 601-700 AR fragment.

Analysis of individual AR mutants with K→A substitution at each of the eight lysine residues within the 601-700 AR fragment identified K630 as the methylation site, because only the K630A mutant abrogated [3H]methyl incorporation from [3H]SAM (Fig. 1, D and E). The K605A mutant consistently showed a weaker methylation signal compared with the other six mutants (Fig. 1E). This is possibly due to a conformation-specific effect of the K605A mutant that limited (but not abrogated) catalytic transfer of the methyl group to K630.

K630-dependent methylation of endogenous AR and association of intracellular AR with Set9

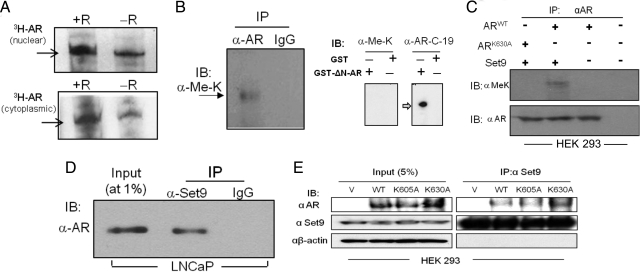

The endogenous AR can be methylated, because 3H-labeled AR was detected within the LNCaP cell nuclear lysate after incubation of the isolated nuclei with [3H]SAM (Fig. 2A, top panel). The cytoplasmic AR from LNCaP cells (cultured in the absence of androgen) was also methylated (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). Methylation was enhanced in the presence of the androgen R1881. pH optimization showed that the intracellular AR was most robustly methylated at a neutral pH. In contrast, a more basic pH (8.5) is optimal for the methylation of histone H3 (Fig. 1B, bottom panel). The high content of positively charged side chains in histone H3 and its high theoretical pI value likely account for the optimal histone H3 methylation at a basic pH.

Fig. 2.

Methylation of endogenous nuclear and cytoplasmic AR and their association with Set9. A (top panel), Methylation of nuclear AR in LNCaP cells. Nuclei isolated from R1881-treated cells were incubated with [3H]SAM in the presence or absence of R1881 (R), and [3H]AR within the AR immunoprecipitate was detected after Western blotting and 7 d of fluorography. A (bottom panel), Methylation of cytoplasmic AR. Total lysates of LNCaP cells (grown in androgen-free media) were incubated with [3H]SAM in the presence or absence of R1881(R). B (left panel), The AR immunoprecipitate (or IgG-incubated control) from the LNCaP cell total lysate was immunoblotted with the pan-methyllysine (Me-K) antibody (Abcam). This antibody can recognize mono-, di-, and tri-methylated lysine. B (right panel), Lack of cross-reactivity of the anti-Me-K antibody to recombinant AR. The recombinant AR (N-terminal deleted, GST-ΔN-AR) produced a strong signal when probed with the AR-C19 antibody (recognizing the AR C-terminal). C, HEK 293A cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding AR (wild type or K630A) and Set9, and the Western blotted AR immunoprecipitate was probed with anti-Me-K and anti-AR antibodies. Wild-type AR transfected cells without Set9 cotransfection, or control, nontransfected cells were also analyzed. D, The Western blotted Set9 immunoprecipitate (and IgG-incubated control) from the LNCaP cell lysate was probed with the anti-AR antibody. The input lysate was at 1% of the lysate used for immunoprecipitation. E, Co-IP of Set9 with AR (wild type, K605A, K630A) from transfected HEK 293A cells. Endogenous Set9 levels were similar in vector- and AR-transfected cells. All AR forms were expressed at similar levels in transfected cells. IB, Immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation; V, vehicle; WT, wild type.

Methylation was lysine specific, because a pan-methyllysine antibody (anti-MeK, AbCam, Cambridge, MA) recognized AR from LNCaP cells in Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B, left panel). This further strengthens the evidence that AR can exist in vivo in a methylated form. No cross-reactivity of the anti-MeK antibody to unmethylated AR was evident (Fig. 2B, right panel). The K630 residue is essential for lysine methylation of intracellular AR, because the MeK-specific antibody recognized transfected wild-type AR but not the K630A mutant in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (Fig. 2C, upper panel). Expression levels of the transfected wild-type and AR-K630A were similar (Fig. 2C, bottom panel). This result is consistent with the in vitro methylation data (Fig. 1, D and E), which shows that AR methylation by Set9 is K630 dependent. These results did not, however, distinguish mono-, di-, and tri-methylated lysine modifications, because the pan-methyl anti-MeK antibody recognized all three forms.

The anti-MeK antibody did not recognize wild-type AR in the absence of Set9 cotransfection, suggesting that under a steady-state condition, the intracellular AR is mostly in an unmethylated form, and in the absence of Set9 overexpression, any methylated AR in HEK 293 cells was below the detection limit of immunoblot probing. A low steady-state level of methylated AR is also indicated by the strong immunoblot signals with the anti-AR antibody in contrast to the weak signal from the anti-MeK antibody (Fig. 2C), assuming, however, that both antibodies recognized cognate antigens with similar efficiency.

AR coimmunoprecipitated with Set9 from the total LNCaP cell lysate, indicating that a fraction of endogenous AR and Set9 remain as part of the same intracellular protein complex (Fig. 2D). This physical proximity is expected to facilitate Set9-mediated methylation of AR. We did not examine whether these two proteins are directly associated with each other. The methylation-site-active wild-type and K605A AR, as well as the methylation-deficient K630A AR, coimmunoprecipitated with Set9 from AR-transfected HEK 293A cells (Fig. 2E).

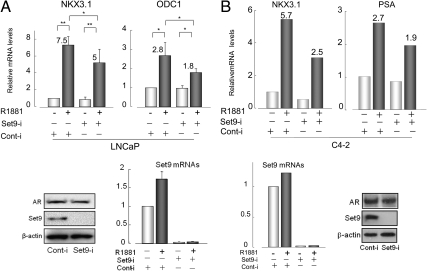

Set9 can associate with AR both in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartment. Thus, each can coimmunoprecipate the other in the high-salt nuclear extract of LNCaP cells (Fig. 3A, upper panel). AR coimmunoprecipitated Set9 from the cytosolic fraction as well (Fig. 3A. lower panel). Caspase 3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 were used as marker proteins for cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively (Fig. 3B). Although the bulk of the LNCaP cell AR translocated to the nucleus in the presence of androgen, a minor fraction of AR was detectable in the cytosol (Fig. 3B, middle panel), possibly due to the recycling of the receptor between the nucleus and cytoplasm (16). The AR-Set9 coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) efficiency was similar in the presence and absence of R1881.

Fig. 3.

Co-IP of Set9 and AR from nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of LNCaP cells. A, Arrows mark coimmunoprecipitated AR and Set9. Co-IP was carried out in the presence or absence of R1881. Asterisks mark immunoprecipitated AR and Set9 from nuclear and cytosolic extracts upon incubation with anti-AR and anti-Set9 antibodies, respectively. B, Caspase 3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 are marker proteins for cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts. Ext, Extract; IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation.

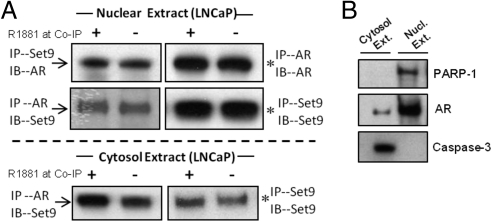

Impact of altered cellular Set9 levels on AR activity and AR target gene expression

Set9 depletion of LNCaP cells reduced androgen-stimulated induction of NKX3.1, ODC1 mRNAs (Fig. 4A) and also the expression of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) mRNAs (data not shown). The Set9-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) pool targeted four separate regions of the Set9 mRNA sequence. Similarly, androgen-stimulated NKX3.1 and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) mRNA expression declined markedly as a result of Set9 silencing in the androgen-independent C4-2 cells (Fig. 4B). The androgen-independent (albeit androgen-sensitive) C4-2 cells originated from the parental LNCaP line. For both cell lines, Set9 mRNAs were ablated by greater than 98% (Fig. 4, A and B, lower panels), and protein levels were similarly reduced. Thus, Set9 enhances the AR transcriptional activity in prostate cancer cells that are either androgen dependent (LNCaP) or androgen independent (C4-2).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of androgen-induced AR target gene expression in Set9-silenced LNCaP and C4-2 cells. A, NKX3.1 and ODC1 mRNA levels (quantified by real-time RT-quantitative PCR and normalized to constant β-actin mRNAs) in control-RNAi or Set9-RNAi-transfected LNCaP cells. Data show average ± sd (three independent duplicate experiments). **, P ≤ 0.01; *, P ≤ 0.05. B, NKX3.1 and PSA mRNA levels in C4-2 cells upon silencing of Set9. Values are averages from two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. Numbers on top of the histograms show fold induction. Induction of PSA in LNCaP cells and ODC1 in C4-2 cells was also reduced upon Set9 depletion (data not presented). A and B (bottom panels), Reduced Set9 mRNA and protein levels in Set9-depleted cells without changes in AR levels.

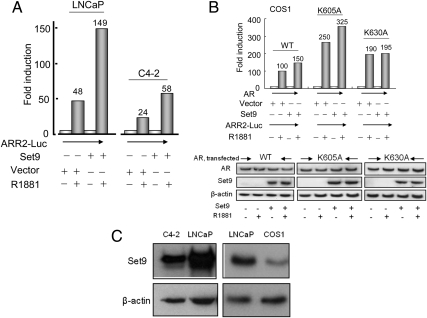

Reciprocally, overexpression of Set9 enhanced AR activity in LNCaP (from 48- to 149-fold) and in C4-2 cells (from 24- to 58-fold) (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, Figs. 4 (A and B) and 5A did not distinguish a direct effect of Set9 (due to AR methylation) from a general coactivation effect of Set9 through changes in the local chromatin structure due to histone methylation.

Fig. 5.

Set9 overexpression enhanced AR-mediated transactivation in a K630-dependent manner. A, R1881-induced luciferase activity from the transfected ARR2-Luc reporter plasmid in LNCaP and C4-2 prostate cancer cells with or without enforced Set9 overexpression. B, Luciferase activities in COS1 (simian kidney) cells that were cotransfected with the plasmids ARR2-Luc, pcDNA3.1-Set9 (or pcDNA3.1), and wild-type or mutant (K605A or K630A) AR. B (bottom panel), Similar levels of wild-type and mutant (K605A and K630A) AR in transfected COS1 cells, revealed from Western blotting. Luciferase activities in panels A and B were normalized to equal protein amounts, and data are presented as averages from two independent transfections, each carried out in duplicate. The numbers show fold induction. C, Endogenous Set9 levels in C4-2 and COS1 cells compared with LNCaP cells. Total cell-lysate proteins (30 μg) were loaded in each lane. WT, Wild type.

That Set9 can exert a direct effect on AR activity due to methylated K630 is indicated by the result that Set9 potentiated AR-mediated transactivation of the probasin gene promoter in COS1 cells in a K630-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). Enforced Set9 expression in COS1 cells enhanced the extent of androgen-mediated induction of luciferase expression from the ARR2-Luc plasmid upon cotransfection with the wild-type AR (from 100-fold to 150-fold) or the methylation site-active K605A mutant AR (from 250-fold to 325-fold). In contrast, the methylation-site-mutant AR (K630A) did not show any significant change in the transcriptional potency when Set9 was overexpressed in COS1 cells (Fig. 5B, third panel). Similar AR expression levels for the wild-type and K605A and K630A mutants are shown (Fig. 5B, bottom panel). A lack of effect of Set9 overexpression on the activity of the K630A mutant was also observed in 293A cells (data not shown). These results support the notion that the Set9 effect on AR activity may not simply be a general coactivation effect; rather, the lysine-630-methylated AR has enhanced transcriptional activity. The relative levels of Set9 in LNCaP, C4-2, and COS1 cells are shown (Fig. 5C).

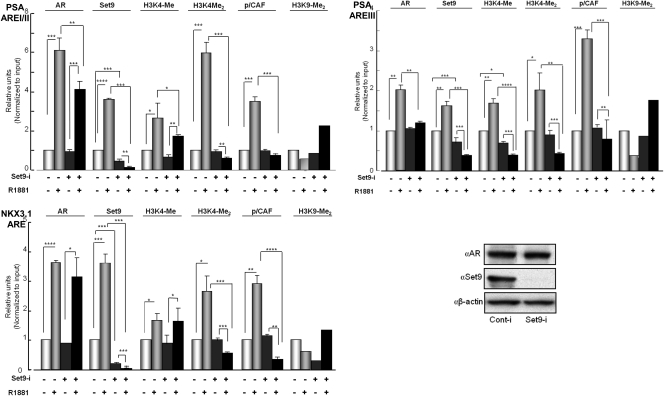

Androgen-induced chromatin recruitment of Set9 to androgen response elements (AREs) in AR target genes and associated changes in methylated histone H3 activation and repressive marks

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed on Set9-depleted and Set9-intact LNCaP cells that were treated with R1881 or vehicle to examine occupancy of AR, Set9, and the coactivator p/CAF at the genomic ARE loci of PSA and Nkx3.1 (Fig. 6). The methylation status of histone H3K4 and H3K9 was also examined. Similar to AR, engagement of Set9 at all three ARE loci increased in the presence of androgen. Set9 depletion resulted in the loss of Set9 from these sites. We note that upon Set9 depletion, hormone-induced AR occupancy was reduced at the AREs of the PSA gene (AREI/II and AREIII), whereas AR occupancy did not change significantly at the ARE located approximately 3 kbp upstream in the Nkx3.1 gene. The androgen-induced recruitment of the p/CAF coactivator at these three AREs was prevented in Set9-depleted cells. The chromatin activation marks from mono- and dimethylated histone H3K4 were abrogated at all three loci upon Set9 depletion. At the same time, the chromatin-repressive mark of histone H3K9-dimethyl increased. All these results provide evidence for Set9 engagement at AREs of the AR target genes PSA and Nkx3.1 in the presence of androgen, and Set9 likely is involved in the formation of AR-associated coactivator complexes at these sites.

Fig. 6.

Effects of Set9 depletion on the chromatin occupancy of AR, p/CAF, and on the activation and repressive methylated histone H3 marks at AREs of AR target genes in LNCaP cells. ChIP was performed with antibodies to AR, Set9, p/CAF, H3K4-monomethyl, H3K4-dimethyl, and H3K9-dimethyl and the nonspecific COX-2 antibody. The PCR primers for ChIP are described in Materials and Methods. ChIP-ed DNAs were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to input DNA (before ChIP). Differential Ct values from experimental and input DNAs (ΔCt) were used to calculate the amplified DNA yield for each experiment. ChIP with anti-COX-2 antibody (negative control) did not show a PCR signal within 30 amplification cycles. For each ChIP, the fold change was calculated relative to the value for vehicle-treated, Set9-intact (control RNAi-treated) cells, which was set as 1. Each independent ChIP data point is the average of normalized values from PCR runs in duplicate wells. Each histogram is the average ± sem from multiple independent ChIP experiments of n = 3 except for the ChIP on H3K9-Me2, where n = 2 so that averages of two independent duplicates are shown. P values are based on Student's t test using the Sigma Plot software. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.00001. Reduction of the Set9 level in Set9 siRNA-incubated LNCaP cells without any change in the AR level is shown.

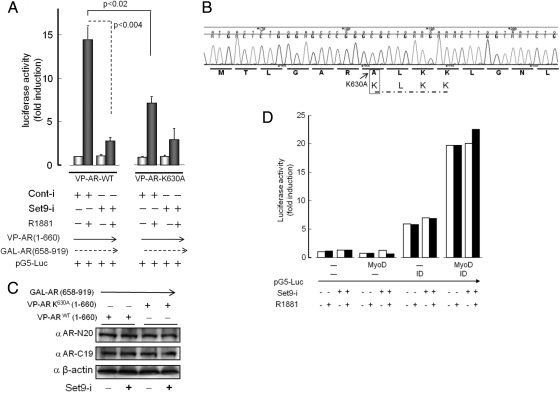

A K630-dependent direct role of Set9 in the AR N-C interaction and in AR's transcriptional activity

The interdomain amino- and carboxy-terminal interaction for AR (N-C interaction) is an important determinant of AR's transcriptional activity (17). Mammalian two-hybrid interaction assay using VP16-AR (AA residues 1-660), which contains AR N-terminal and DNA-binding domains, and GAL4-AR (AAs 658-919), which contains hinge and ligand-binding domains of AR, showed that the androgen-dependent stimulation of luciferase expression from the pG5-Luc reporter plasmid (containing five copies of the GAL4 DNA-binding sequence) markedly decreased in Set9-silenced COS1 cells (Fig. 7A, left panel; P < 0.004). The K630A substitution in VP16-AR (AAs 1-660) weakened N-C interaction (Fig. 7A, right panel; P < 0.02). The K630A mutant showed further decline in the N-C interaction upon Set9 knock down, which indicates an additional K630-independent Set9 effect on the N-C interaction. N-C interaction in 293A and PC3 cells showed similar results. K630A substitution was authenticated by nucleotide sequencing of the mutant VP16-AR (AAs 1-600) (Fig. 7B). Similar expression levels of the wild-type and mutant VP16-AR and the GAL4-AR (AAs 658-919) are shown (Fig. 7C). In a control experiment, the interaction between MyoD and ID (the inhibitory DNA-binding protein) was unaffected by Set9 silencing (Fig. 7D). These data, taken together, strongly suggest that the AR N-C interaction is regulated by Set9 in a K630-dependent manner.

Fig. 7.

The role of Set9 and lysine methylation in AR N-C interaction. A, In mammalian two-hybrid assay, COS1 cells were transfected with a Set9-specific siRNA pool (Set9-i) or a nonsilencing siRNA pool (Cont-i), pG5 luciferase reporter plasmid, the DNA-binding GAL4-AR (AAs 658-919) plasmid, and the VP16-AR (AAs 1-660) plasmid, which contains either a lysine-630 (VP-AR-WT) or the alanine-substituted 630 residue (VP-AR-K630A). Luciferase activities were normalized to equal protein amounts, and data are presented as average (±sem) of three independent transfections, each performed in duplicate. B, Sequencing profile of the mutant VP-AR-K630A plasmid DNA. The boxed region confirms alanine substitution for lysine-630 at the wild-type 630KLKK633 motif. C, Comparable expression of transfected VP-AR-WT and VP-AR-K630A in Set9-intact and Set9-depleted cells, and similar levels of GAL4-AR (AAs 658-919) expression in all cases. D, Set9 depletion did not alter the strength of interaction between MyoD (and ID (inhibitory DNA-binding protein). Average values from two experiments are shown.

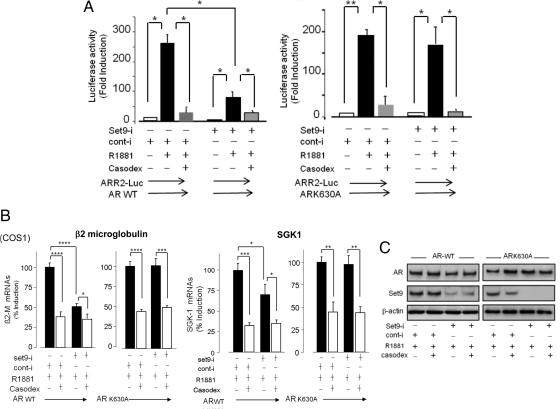

The likelihood of a direct action of endogenous Set9 on AR activity was examined in transfected COS1 cells. The wild-type AR induced the probasin gene promoter at the androgen response region, causing robust luciferase gene induction from ARR2-Luc in R1881-treated cells. Induction was reduced by 80% (250-fold vs. 50-fold) in Set9-silenced cells (Fig. 8A, left panel). In contrast, the K630A mutant caused similar levels of induction of ARR2-Luc in Set9-intact and Set9-depleted COS1 cells (Fig. 8A, right panel). The AR antagonist casodex inhibited the androgen-induced receptor activity under all conditions. The androgen-dependent, casodex-sensitive induction of the endogenous AR target genes β2-microglobulin and SGK1 was unaffected by Set9 depletion in COS1 cells that were transfected with the K630A mutant (Fig. 8B). On the other hand, Set9 depletion in the wild-type AR-transfected cells caused significant decline in the androgen-dependent induction of β2-microglobulin and SGK1 (by 50% for β2-microglobulin; by 40% for SGK1) (Fig. 8B). Similar expression of the wild-type and mutant K630A AR and a marked Set9 depletion in the presence of Set9-siRNAs are shown (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Set9 depletion reduced androgen-induced AR activity and AR target gene expression in COS1 cells. A, Androgen-induced luciferase activity of ARR2-Luc in Set9-depleted and Set9-intact COS1 cells that were cotransfected with wild-type or K630A mutant AR. Composite results (±sem) from four independent duplicate assays are shown. Luciferase activities in androgen-treated cells are shown relative to vehicle-treated cells. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01. B, Set9 depletion reduced androgen-stimulated induction of β2-microglobulin and SGK1 mRNAs in COS1 cells transfected with wild-type AR, but not the K630A mutant AR. The mRNAs were quantified by real-time qRT-PCR and normalized to invariant β-actin mRNAs. Casodex-mediated decrease of androgen-induced target gene expression is shown (open bars). The mRNA levels are presented as percent induction by R1881 compared with vehicle-treated cells. Percent induction is computed as the average ± sem, n = 3 independent assays, each performed in duplicate. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. C, Similar levels of wild-type and K630A AR expression in transfected COS1 cells. Set9 was depleted in siRNA (Set9)-incubated cells. WT, Wild type. β2-M, β2-microglobulin; Set9-i, Set9-specific siRNAs; Conti-i, control siRNAs.

The results in Figs. 7 and 8, taken together, lead us to conclude that AR activity is under direct positive regulation by Set9 due to methylation of K630. Thus, Set9 likely plays a dual role in enhancing AR transcriptional activity: a direct role by targeting AR for lysine methylation at K-630, when N-C interaction is strengthened, and a general coactivator role that involves histone tail modification by methylation of histone H3K4 at the ARE loci in the target gene chromatin.

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that the lysine-630 of AR is a substrate for the Set domain containing Set9 methyltransferase, and that methylation bestows AR with enhanced transcriptional activity and stronger N-C interaction. We show the following: 1) Methylation of AR was catalyzed by Set9 in vitro and in vivo at lysine-630, which is a hinge domain located AA. Of the eight lysine residues in the AR hinge domain, methylation was abrogated only for the lysine-630 substitution to alanine (K630A). The single AA substitutions K→A at positions 605, 609, 618, 632, 633, 638, and 658 did not prevent Set9-mediated methylation of a GST-fused AR fragment (AAs 601-700). Set9 methylated both cytoplasmic and nuclear AR, and androgen enhanced the extent of methylation. Set9 associated with both nuclear and cytoplasmic AR in co-IP assays. A pan-methyllysine antibody immunorecognized the methylation-competent AR containing lysine-630, but not the K630A mutant in transfected cells; 2) Depletion of endogenous Set9 (by RNA interference) reduced the transcriptional activity of the wild-type AR and the androgen-mediated AR target gene expression; this reduction was prevented by the K630A substitution. Reciprocally, Set9 overexpression potentiated the activity of the AR wild type, but not the K630A mutant; 3) N-C interaction was significantly weaker for the K630A mutant compared with the wild-type AR, and Set9 silencing caused a precipitous decline in the N-C interaction of the wild-type AR. These results make a strong case that methylation at lysine-630 leads to enhanced transcriptional activity of AR.

While our work was in revision, a report was published online to show that AR is methylated by Set9 at lysine-632 (18, Nucleic Acids Res, October 19, 2010, doi: 10.1093/nar/). The authors reported that methylation of an AR hinge domain peptide (AAs 623-640), harboring the 630KLKK633, was abrogated when lysine-632 was substituted by arginine. Our results, however, show that the K632A mutant in the GST-AR fragment was methylation competent (Fig. 1D). A much longer AR fragment (AAs 601-700), as used in our study, is likely to have a very different conformation at the KLKK motif than an 18-mer peptide, as used in the other study (18). In our study, the pan-methyllysine antibody did not recognize the AR-K630A immunoprecipitate from transfected HEK 293A cells (Fig. 2C), and the AR N-C interaction was much weaker for the K630A mutant relative to the wild-type AR (Fig. 7A). Additionally, Set9 depletion reduced transactivation mediated by the wild-type receptor but not the K630A mutant (Fig. 8). In a second study, where increased stability of ERα due to Set9-catalyzed methylation at the hinge domain KLKK motif was demonstrated, the authors could not detect methylation of an AR peptide substrate (from 622–642) by recombinant Set9 (19). The discrepancy between our results and the results reported by Gaughan et al. (18) needs to be resolved.

K630, K632, and K633 are known sites of acetylation mediated by p/CAF and Tip60 (8, 13). The acetylation site mutants K632A and K633A did not prevent AR methylation (Fig. 1D). Androgen-mediated induction of the Pem (Rhox5) gene promoter, which is a Sertoli cell-expressed AR target gene, was completely abrogated when K630, K632, and K633 residues were substituted with alanine, whereas AR mutations that prevented N-C interaction were still active in mediating androgen-dependent induction of the Pem promoter (20). Our results, i.e. that Set9 had a K630-dependent positive influence on AR N-C interaction and AR-mediated transcription of the AR target genes β2-microglobulin and SGK1, suggest a promoter-selective functional link between AR N-C interaction and altered AR activity through lysine modification.

In a dual role, Set9 appears to serve as a coactivator in the induction of AR target genes, in addition to its direct influence on the AR activity through lysine-630 modification. The chromatin structure at active gene sites often shows mono- and dimethylated lysine-4 (K4) of histone H3 (21, 22), whereas gene repression is linked to histone H3-lysine 9 dimethylated chromatin (23). We show that mono- and dimethylation of lysine-4 of the histone H3 at AREs of the PSA and Nkx3.1 genes paralleled the androgen-induced recruitment of Set9 and the p/CAF histone acetyltransferase, along with AR. This coactivation effect of Set9 is likely to be independent of its effect on AR activity via lysine modification, because Set9 coimmunoprecipitated both methylation-active (wild type, K605A) and methylation-inactive (K630A) AR (Fig. 2E). Set9 depletion reduced K4-methylated histone H3 and p/CAF, while increasing the presence of the H3K9-dimethyl-repressive mark at AREs. We observed that Set9 depletion reduced AR occupancy at the PSA gene AREs (ARE I/II and ARE III) but not at the upstream ARE of Nkx3.1 (Fig. 6). The mechanistic implication of this ARE-selective Set9 dependence for the chromatin engagement of AR is not understood at the present time.

The AR hinge domain is known to harbor a repressor subdomain (AA residues 628-646) that interacts with multiple coregulators such as the small nuclear ring finger protein, which facilitates ligand-mediated nuclear translocation of AR (24) and the actin-binding cytoskeletal protein filamin A, which interferes with interdomain N-C interaction of AR and represses AR-mediated transactivation by competing with the p160 coactivator transcriptional intermediary factor 2/glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 (25). Cyclin D1 binds to the hinge region through its acid-rich carboxyl terminus and inhibits ligand-dependent AR activity by competing for the limiting cellular p300/CREB-binding protein-associated factor p/CAF (26). It is conceivable that upon methylation, AR-K630 serves as a sign post either for recruiting a hinge domain-binding coactivator or for preventing association of this region with a corepressor. Additional studies are needed to sort out these different possibilities and to explore whether K-630 methylation of AR is reversible by the lysine-specific demethylase LSD1 (27).

Given the overlapping methylation and acetylation site at K630, and dependence of acetyltransferase and methyltransferase on the respective cofactors (acetyl-coenzyme A and SAM), we speculate that competing dynamics between acetylation and methylation of AR at K630 may be guided by redox, metabolic, and nutritional states of cells. Somatic mutation in the genomic AR leading to the K630 →T AA change in AR has been identified in prostate cancer. K630T mutation increased AR transcriptional activity, AR interaction with coactivators, and AR-regulated growth of xenograft tumors from human prostate cancer cells (13, 28). It is conceivable that fine tuning of AR activity, needed to support specific metabolic or nutritional changes, involves methyl or acetyl modification of AR. On the other hand, prostate cancer-associated K630T AA change may cause phosphorylation of the 630 AA by a putative threonine-specific kinase, when the negatively charged phosphate group would markedly alter the interaction dynamics of AR with coactivator(s). This alteration can potentially raise AR activity to a pathological level, which promotes uncontrolled prostate cell proliferation that culminates in prostate cancer development.

Materials and Methods

Methylation of AR in vitro and in vivo, GST-fused AR, and Set9

A mixture of GST-Set9 and GST-AR (wild type or bearing K→A substitution) was incubated with 1 μm [3H-methyl]SAM (78 Ci/mmol, catalog no. NET155H, Perkin-Elmer Corp., Wellesley, MA) at 30 C, 2 h in a reaction buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 4 mm dithiothreitol, as described elsewhere (29). Reaction products were run on 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membrane, which was sprayed with EN3HANCE (Perkin-Elmer) and fluorographed for 7 d.

Truncated AR cDNAs were derived from full-length human AR cDNAs by PCR, subcloned in pGEX4T2, and expressed in the Escherichia coli BL21RP by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside induction. Point mutations were introduced into AR cDNAs using a QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and appropriate mutant oligos. Mutants were confirmed by nucleic acid sequencing. Upon transfection into mammalian cells, the mutagenized cDNAs produced AR variants with desired AA substitutions. The Set9 full-length cDNA was cloned from LNCaP cells by RT-PCR, sequence verified, and subcloned into pGEX4T2 or into pcDNA3.1. Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21RP under isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside induction and affinity purified on glutathione-Sepharose.

The endogenous AR in LNCaP cell nuclei was methylated under a neutral pH reaction condition by incubating the nuclei with [3H]SAM. 3H-labeled AR was identified by fluorography of the SDS-PAGE-fractionated AR immunoprecipitate. A nuclei isolation kit (NUC-101; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was used to isolate nuclei from LNCaP cells that were cultured for 2 d in charcoal-stripped serum and then for an additional day in the stripped serum containing 1 nm R1881 to induce nuclear translocation of AR. The nuclei were taken up in 100 μl of nuclei EZ lysis buffer, pH 7.4 (product N3408, Sigma) containing 1 μm [3H]SAM and incubated at 30 C for 60 min in the absence or presence of 1 nm R1881. The reaction was stopped by adding 400 μl of a lysis buffer (40 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 125 mm NaCl; 1%Triton X-100; 2 mm EDTA; 10% glycerol) along with phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (1 mm) and a cocktail of complete protease inhibitors (Roche). AR was immunoprecipitated from the reaction mixture by overnight incubation at 4 C with 2 μl of the AR antibody (N-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) followed by incubation with Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 2 h at 4 C. The bead-associated AR immunoprecipitate was captured on a DynaMag magnetic particle concentrator, washed (three times with the nuclear lysis buffer), and eluted at 98 C by the Laemmli's sample buffer. The denatured sample was fractionated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane, and the 3H-labeled AR was detected by fluorography of the membrane for 7 d on a Kodak XAR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Set9 depletion of cells

Cells were transfected with siRNA pools or nontargeting siRNA pools (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) for 72 h. Each siRNA pool has four distinct targeting sequences as follows. Set9 siRNAs: 5′-GGAGUGUGCUGGAUAUAUUUU; 5′-CAAACUGCAUCUACGAUAUUU; 5′-CUGGACGAUGACGGAUUAUU; and 5′-AGAGGACCGCACUUUAUGUU (Dharmacon; catalog no. M-014643-00-0005). Nontargeting siRNAs: 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA; 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUUGUGUGA; 5′-UGG-UUUACAUGUUUUCUGA and 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCCUA (Dharmacon, catalog no. D-001810-01-20).

ChIP in Set9-depleted LNCaP cells

The cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes (∼10 × 106 cells each dish) and kept overnight at 37 C in a complete medium [RPMI-1640, phenol red free plus antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin) and charcoal-stripped serum (CSS) at 5%]. The medium was changed to phenol red free RPMI-1640 (without antibiotics and CSS) and 4 h later, the cells were transfected with 50 nm of Set9-siRNA pool or control-siRNA pool using oligofectamine (Dharmacon). At 4 h after transfection, the medium was switched back to RPMI-1640, antibiotics plus 5% CSS. At 72 h after incubation with siRNAs, fresh complete media (with 5% CSS) was added, and 3 h later, cells were treated with R1881 (1 nm) or vehicle (0.001% ethanol) for 45 min and then fixed by 1% formaldehyde. The chromatin DNA, cross-linked to proteins, was processed for ChIP as before (30, 31). ChIP-PCR detected R1881-dependent recruitment of AR, Set9, the p/CAF coactivator, and the methylation status of histone H3K4 (monomethyl; dimethyl) and H3K9 (dimethyl) at target gene loci. The PCR primer sequences are: PSA, ARE-I/II: 5′-GCTAGCACTTGCTGTTCTGC (sense); 5′-AGGGATCAGGGAGTCTCACA (antisense). PSA, ARE-III: 5′-CTGAGCAAAGACAGCAA-CACC(sense); 5′-GGATTGAAAACAGACCTACTC (antisense). Nkx3.1, ARE: 5′-TGTCTTTGGAGGA-CACTGGA(sense); 5′-TTGGCAAAGCTGGTTTTCTT (antisense). The antibody sources: AR (N-20), Set9 (V-20), p/CAF from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; H3K4-Me; H3K4-(Me)2; H3K9-(Me)2 from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Quantification of ChIP-PCR data is detailed in the Figure legend.

Endogenous mRNAs and the luciferase reporter activity in Set9-depleted cells

Endogenous mRNA levels were quantified by real-time quantitative PCR of reverse transcripts and normalized to constant β-actin mRNA expression. RNAs from harvested cells were isolated using TRIZOL (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR amplification of the cDNAs were performed as before (30, 31). AR-negative COS-1cells were seeded in 12-well flasks, grown overnight in the presence of 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) without antibiotics, and then transfected concurrently with the siRNA pool, 100 nm (Set9-specific or control, nontargeting) and AR expression plasmid, 50 ng (wild type or mutant) using Lipofectamine 2000. For reporter gene assay, the plasmid ARR2-Luc (200 ng) was also included, and 24-well flasks were used. At 2 d after transfection, cells were treated for 24 h with R1881 (10 nm) or vehicle (0.01% ethanol) and then harvested for mRNA quantification or luciferase assay.

LNCaP and C4-2 cells were seeded in 12-well flasks in the presence of 5% CSS containing medium (RPMI-1640, phenol red free), without antibiotics. The siRNA pool at 100 nm (control or Set9 targeting) was transfected into the cells using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). At 2 d after transfection, R1881 (1 nm) or vehicle was added to the medium and 24 h later cells were harvested for mRNA analysis. PCR primers were as follows: 1) β2-microglobulin: 5′-GCTGTGCTCGCGCTACTCTC (sense); 5′-CAATGTCGGATGGATGAAACC (antisense); 2) SGK-1: 5′-CCTTGTGGATATGCTGTGTGAACCG (sense); SGK-1 5′-TGGGGCATTGGTCCATAAAAACC (antisense); 3) ODC1: 5′-TGATTGG-ATGCTCTTTGAAAACAT (sense); 5′-ACACATTAATACTAGCCGAAGCAC (antisense); NKX3.1: 5′-CTGTCAGCCCCTGAACGG (sense); 5′-AACCATATCTTCACTTGGGTCTCC (antisense); PSA: 5′-TATTTCCAATGACGTGTG (sense); 5′-TGCACCACCTTGGTGTACAGG (antisense); β-actin: 5′-CGTACCACTGGCATCGTGAT (sense); 5′-GTGTTGGCGTACAGGTCTTT (antisense).

Enforced Set9 expression and luciferase activity from the ARR2-Luc plasmid

LNCaP and C4-2 human prostate cancer cells were seeded in 24-well flasks and cotransfected with the ARR2-Luc reporter (200 ng) plasmid and Set9 expression plasmid at 100 ng (or the vector plasmid). For COS-1 cells, an AR-encoding plasmid at 50 ng (wild type or mutant) was cotransfected with ARR2-Luc (200 ng) and the Set9 expression plasmid (100 ng). DNA amounts were normalized to equal amounts in all wells using vector DNA. Cells were grown in CSS-phenol red free medium for 2 d, seeded overnight on 24-well plates, and transfected with an appropriate plasmid combination using Fugene 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN); 24 h later cells were treated with vehicle (0.01% ethanol) or R1881 (1 nm) for 24 h, after which cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity (luciferase kit; Promega Corp., Madison, WI). Values were normalized to constant protein amounts (Bradford assay). Maintenance media: DMEM, 5% FBS (for COS-1): RPMI-1640, 5% FBS (for LNCaP); DMEM, 5% FBS, 20% HAM'S F12, 5 μg/ml insulin, 13.65 pg/ml T3, 4.4 μg/ml apo-transferrin, 0.244 μg/ml d-biotin, 12.5 μg/ml adenine (for C4-2). Antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin) were included in all maintenance media.

Western blot and co-IP

A pan-methyllysine-specific antibody (Abcam) was used to detect the methylated form of intracellular AR. Co-IP of Set9 and AR in nuclear and cytosolic fractions of LNCaP cells were examined. The supernatant from pelleted nuclei (isolated using the NUC-101 nuclei isolation kit) was saved as the cytosol fraction. The nuclei were incubated with a high-salt extraction buffer [0.45 m NaCl, 50 mm Tris·HCl, (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 2 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, Cocktail of Complete Protease Inhibitors (Roche)] at 4 C with rotation for 1 h. The nuclear extract was diluted 3-fold with a dilution buffer (the extraction buffer as above, except without any NaCl), cleared by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 20 min, 4 C) and then incubated overnight with rotation at 4 C with anti-AR or anti-Set9 antibody followed by incubation with Dynabeads Protein G for 30 min at 4 C. The bead-bound immunoprecipitates were captured on the DynaMag magnet, washed twice with the dilution buffer, and then dissociated from the beads, after which the recovered supernatant (using Laemmli's sample buffer at 98 C) was used for Western blot assay after fractionation on 10% SDS-PAGE. The cytosolic fraction was similarly processed for co-IP. Co-IP in AR-transfected HEK 293 cells was performed with total cell lysates.

N-C interaction of AR

COS1 cells, seeded overnight in 24-well flasks at 50% confluency in CSS, phenol red free medium, were transfected with Set9 siRNA pool (100 nm) or control siRNA pool together with pG5-Luc (100 ng), and 50 ng each of GAL-AR (AAs 658-919) and VP-AR (AAs 1-160), using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 0.1 nm R1881 or vehicle (0.01% ethanol) for 24 h. The luciferase activity of cell lysates [in the Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega)] was assayed and normalized to equal protein amounts (Bradford assay).

The plasmid VP16-AR (AAs 1-660) encodes the chimeric VP16 transactivation domain and the wild-type N-terminal AR (AA residues 1-660); GAL4-AR (AAs 658-919) expresses the GAL4 DNA-binding domain in frame with the C-terminal AR (AA residues 658-919). These plasmids were gifts from Dr. Elizabeth M. Wilson (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). The K-630A mutant VP16-AR (AAs 1-660) was generated using the same primer set as used to construct the full-length K630A AR and was confirmed by sequencing the plasmid DNA at the target site. pG5-Luc (Promega) contains the GAL4-binding site as five tandem repeats. Similar expression levels of VP16-AR (AAs 1-660) and GAL4-AR (AAs 658-919) were confirmed by Western blotting using the N-terminal-specific anti-AR (N-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and C-terminal-specific anti-AR (C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The plasmids pACT-MyoD and pBIND-ID (Promega) and the corresponding empty vectors were gifts from Dr. Tom Boyer.

Statistics

Calculation of sem and Student's t test was done using Sigma plot software. P values <0.05 were statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Liheng Shi for full-length Set9 cDNA, Elizabeth Wilson (Chapel Hill, NC) for N-C interaction plasmids, Tom Boyer (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio) for pACT-MyoD and pBIND-ID plasmids, Rong Li (University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio) for valuable discussion, and Ibtissam Echchgadda (Chatterjee Laboratory) for useful comments. B.C. is a Senior Career Scientist at the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-AG10486 and R01-AG19660; a Veterans Affairs Merit-Review grant, a Department of Defense predoctoral fellowship, XWH-08-1-0067 (to S. Ko.); and a Clinical and Translational Science Award-Translational Science Training predoctoral fellowship (to J.A.).

Disclosure Summary: None of the authors have anything to disclose.

NURSA Molecule Pages:

Coregulators: AR;

Ligands: R1881.

Footnotes

- AA

- Amino acid

- AR

- androgen receptor

- ARE

- androgen response element

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- co-IP

- coimmunoprecipitation

- CSS

- charcoal-stripped serum

- GST

- glutathione-S transferase

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- N-C interaction

- amino- and carboxy-terminal interaction

- p/CAF

- p300/CBP associated factor

- PSA

- prostate- specific antigen

- SAM

- S-adenosyl methionine

- SET

- Su(var)3–9, Ez, and Trx

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TAF

- TATA-binding protein-associated factor.

References

- 1. Chuikov S, Kurash JK, Wilson JR, Xiao B, Justin N, Ivanov GS, McKinney K, Tempst P, Prives C, Gamblin SJ, Barlev NA, Reinberg D. 2004. Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature 432:353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kouskouti A, Scheer E, Staub A, Tora L, Talianidis I. 2004. Gene-specific modulation of TAF10 function by SET9-mediated methylation. Mol Cell 14:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masatsugu T, Yamamoto K. 2009. Multiple lysine methylation of PCAF by Set9 methyltransferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 381:22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee YH, Coonrod SA, Kraus WL, Jelinek MA, Stallcup MR. 2005. Regulation of coactivator complex assembly and function by protein arginine methylation and demethylimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:3611–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng Q, Yi P, Wong J, O'Malley BW. 2006. Signaling within a coactivator complex: methylation of SRC-3/AIB1 is a molecular switch for complex Disassembly. Mol Cell Biol 26:7846–7857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Naeem H, Cheng D, Zhao Q, Underhill C, Tini M, Bedford MT, Torchia J. 2007. The activity and stability of the transcriptional coactivator p/CIP/SRC-3 are regulated by CARM1-dependent methylation. Mol Cell Biol 27:120–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Faus H, Haendler B. 2006. Post-translational modifications of steroid receptors. Biomed Pharmacother 60:520–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang C, Powell MJ, Popov VM, Pestell RG. 2008. Acetylation in nuclear receptor signaling and the role of sirtuins. Mol Endocrinol 22:539–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fu M, Wang C, Reutens AT, Wang J, Angeletti RH, Siconolfi-Baez L, Ogryzko V, Avantaggiati ML, Pestell RG. 2000. p300 and p300/cAMP-response element-binding protein-associated factor acetylate androgen receptor at sites governing hormone-dependent transactivation. J Biol Chem 275:20853–20860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Callewaert L, Verrijdt G, Haelens A, Claessens F. 2004. Differential effect of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-ylation of the androgen receptor in the control of cooperativity on selective versus canonical response elements. Mol Endocrinol 18:1438–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gioeli D. 2005. Signal transduction in prostate cancer progression. Clin Sci 108:293–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin HK, Wang L, Hu YC, Altuwaijri S, Chang C. 2002. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitylation and degradation of androgen receptor by Akt require Mdm2 E3 ligase. EMBO J 21:4037–4048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fu M, Rao M, Wu K, Wang C, Zhang X, Hessien M, Yeung YG, Gioeli D, Weber MJ, Pestell RG. 2004. The androgen receptor acetylation site regulates cAMP and AKT but not ERK-induced activity. J Biol Chem 279:29436–29449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi XB, Ma AH, Xia L, Kung HJ, de Vere White RW. 2002. Functional analysis of 44 mutant androgen receptors from human prostate cancer. Cancer Res 62:1496–1502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kontaki H, Talianidis I. 2010. Lysine methylation regulates E2F1-induced cell death. Mol Cell 39:152–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tyagi RK, Lavrovsky Y, Ahn SC, Song CS, Chatterjee B, Roy AK. 2000. Dynamics of intracellular movement and nucleocytoplasmic recycling of the ligand-activated androgen receptor in living cells. Mol Endocrinol 14:1162–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. He B, Lee LW, Minges JT, Wilson EM. 2002. Dependence of selective gene activation on the androgen receptor NH2- and COOH-terminal interaction. J Biol Chem 277:25631–25639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaughan L, Stockley J, Wang N, McCracken SRC, Treumann A, Armstrong K, Shaheen F, Watt K, McEwan IJ, Wang C, Pestell RG, Robson CN. 19 October 2010. Regulation of the androgen receptor by SET9-mediated methylation. Nucleic Acids Res 10.1093/nar/gkq861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Subramanian K, Jia D, Kapoor-Vazirani P, Powell DR, Collins RE, Sharma D, Peng J, Cheng X, Vertino PM. 2008. Regulation of estrogen receptor α by SET7 lysine methyltransferase. Mol Cell 30:336–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Faus H, Haendler B. 2008. Androgen receptor acetylation sites differentially regulate gene control. J Cell Biochem 104:511–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, Schreiber SL, Mellor J, Kouzarides T. 2002. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419:407–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. 2007. The mammalian epigenome. Cell 128:669–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129:823–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poukka H, Karvonen U, Yoshikawa N, Tanaka H, Palvimo JJ, Jänne OA. 2000. The RING finger protein SNURF modulates nuclear trafficking of the androgen receptor. J Cell Sci 113:2991–3001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loy CJ, Sim KS, Yong EL. 2003. Filamin-A fragment localizes to the nucleus to regulate androgen receptor and coactivator function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:4562–4567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reutens AT, Fu M, Wang C, Albanese C, McPhaul MJ, Sun Z, Balk SP, Jänne OA, Palvimo JJ, Pestell RG. 2001. Cyclin D1 binds the androgen receptor and regulates hormone-dependent signaling in a p300/CBP associated factor (P/CAF)-dependent manner. Mol Endocrinol 49:797–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wissmann M, Yin N, Müller JM, Greschik H, Fodor BD, Jenuwein T, Vogler C, Schneider R, Günther T, Buettner R, Metzger E, Schüle R. 2007. Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat Cell Biol 9:347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fu M, Rao M, Wang C, Sakamaki T, Wang J, Di Vizio D, Zhang X, Albanese C, Balk S, Chang C, Fan S, Rosen E, Palvimo JJ, Jänne OA, Muratoglu S, Avantaggiati ML, Pestell RG. 2003. Acetylation of androgen receptor enhances coactivator binding and promotes prostate cancer cell growth. Mol Cell Biol 23:8563–8575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nishioka K, Chuikov S, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Allis CD, Tempst P, Reinberg D. 2002. Set9, a novel histone H3 methyltransferase that facilitates transcription by precluding histone tail modifications required for heterochromatin formation. Genes Dev 16:479–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ko S, Shi L, Kim S, Song CS, Chatterjee B. 2008. Interplay of nuclear factor-κB and B-myb in negative regulation of androgen receptor expression by tumor necrosis factor α. Mol Endocrinol 22:273–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shi L, Ko S, Kim S, Echchgadda I, Oh TS, Song CS, Chatterjee B. 2008. Reciprocal dynamics of the tumor suppressor p53 and poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase PARP-1 regulates loss of androgen receptor in aging and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 283:36474–36485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]