Abstract

We have sequenced the virulent Asibi strain of yellow fever virus and compared this sequence to that of the 17D vaccine strain, which was derived from it. These two strains of viruses differ by more than 240 passages. We found that the two RNAs, 10,862 nucleotides long, differ at 68 nucleotide positions; these changes result in 32 amino acid differences. Overall, this corresponds to 0.63% nucleotide sequence divergence, and the changes are scattered throughout the genome. The overall divergence at the level of amino acid substitution is 0.94%, but these changes are not randomly distributed among the virus protein. The capsid protein is unchanged, while proteins NS1, NS3, and NS5 contain 0.5% amino acid substitutions, and proteins ns4a and ns4b average 0.8% substitutions. In contrast, proteins ns2a and ns2b have 3.0 and 2.3% amino acid divergence, respectively. The envelope protein also has a relatively high rate of amino acid change of 2.4% (a total of 12 amino acid substitutions). The large number of changes in ns2a and ns2b, which are largely conservative in nature, may result from lowered selective pressure against alteration in this region; among flaviviruses, these polypeptides are much less highly conserved than NS1, NS3, and NS5. However, many of the amino acid substitutions in the E protein are not conservative. It seems likely that at least some of the difference in virulence between the two strains of yellow fever virus results from changes in the envelope protein that affect virus binding to host receptors. Such differences in receptor binding could result in the reduced neurotropism and vicerotropism exhibited by the vaccine strain.

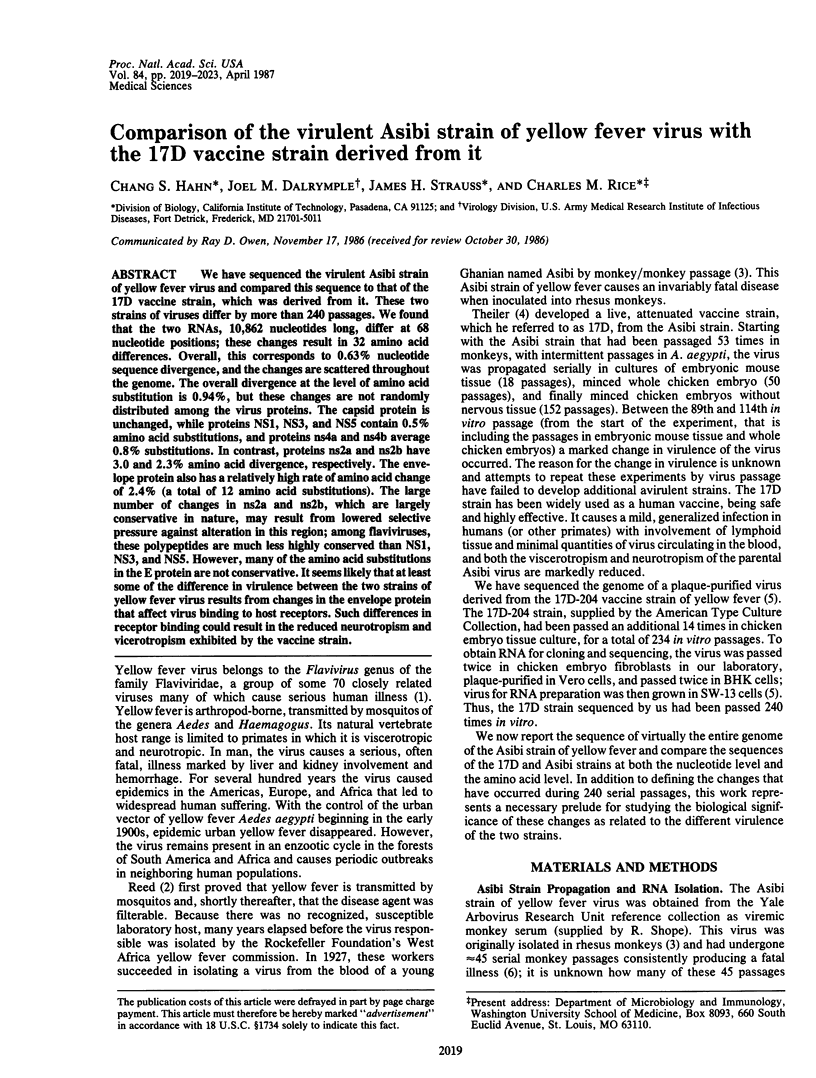

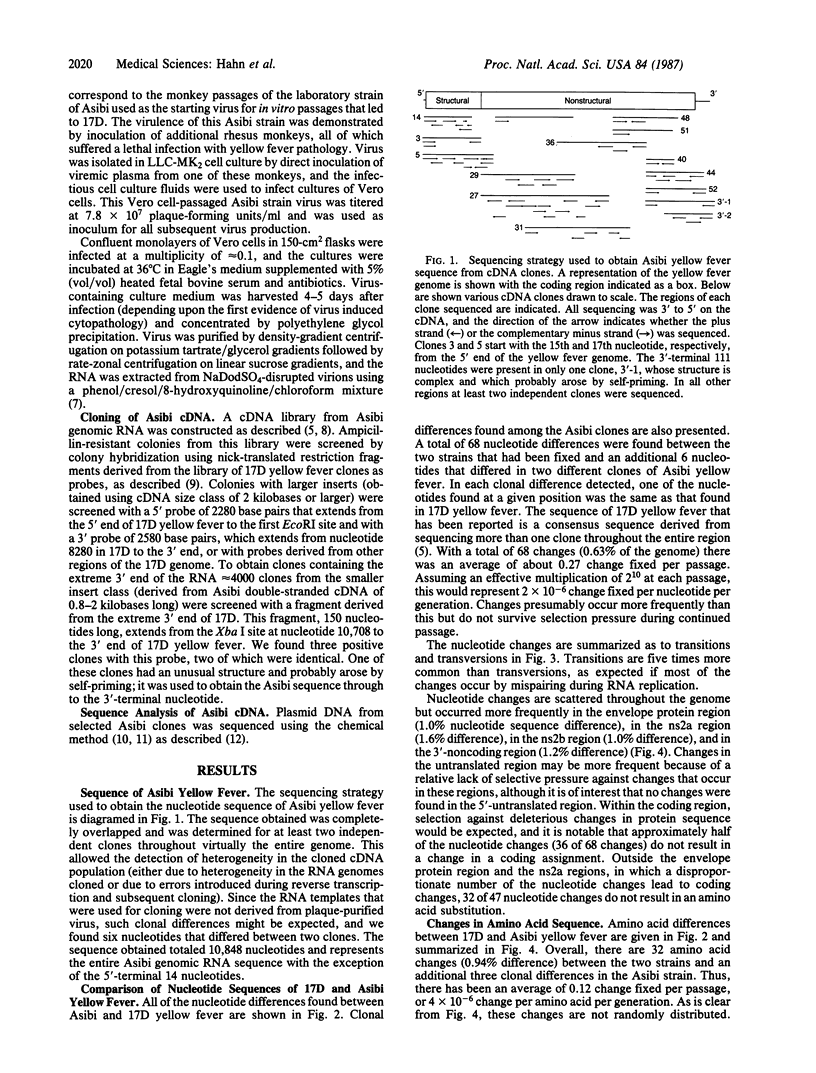

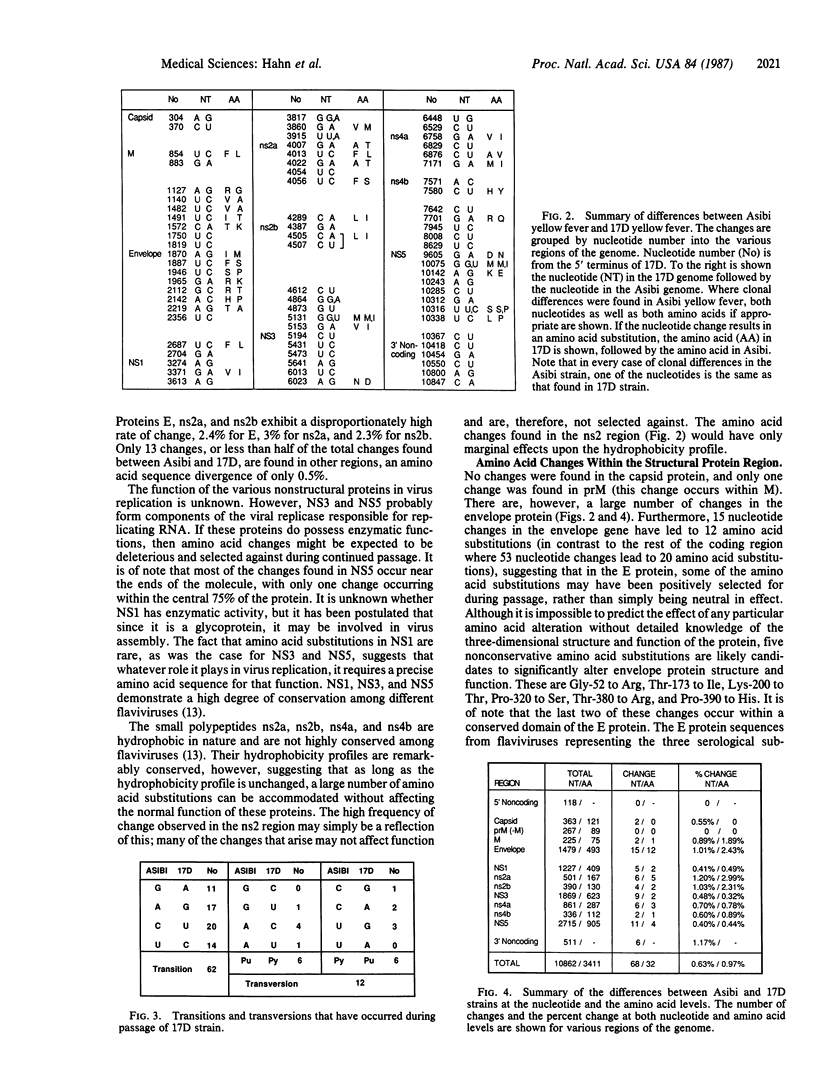

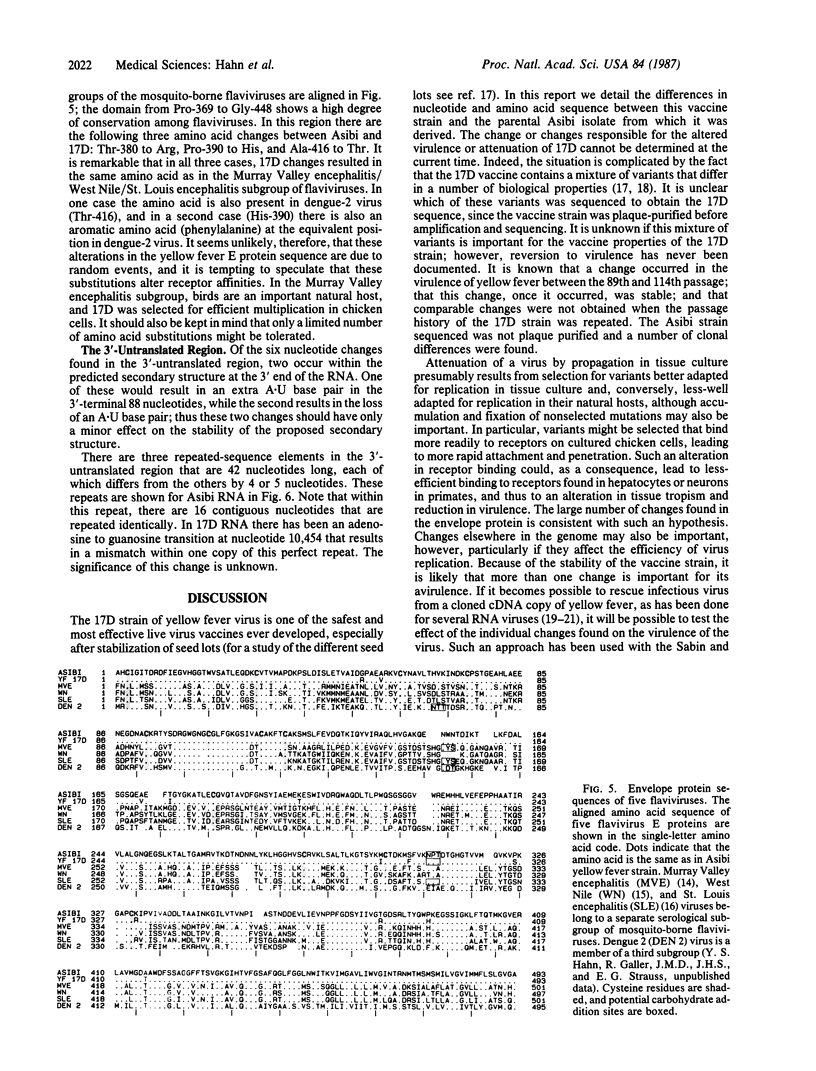

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahlquist P., French R., Janda M., Loesch-Fries L. S. Multicomponent RNA plant virus infection derived from cloned viral cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Nov;81(22):7066–7070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgarno L., Trent D. W., Strauss J. H., Rice C. M. Partial nucleotide sequence of the Murray Valley encephalitis virus genome. Comparison of the encoded polypeptides with yellow fever virus structural and non-structural proteins. J Mol Biol. 1986 Feb 5;187(3):309–323. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E., Sabo D., Taniguchi T., Weissmann C. Nucleotide sequence heterogeneity of an RNA phage population. Cell. 1978 Apr;13(4):735–744. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J., Spindler K., Horodyski F., Grabau E., Nichol S., VandePol S. Rapid evolution of RNA genomes. Science. 1982 Mar 26;215(4540):1577–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.7041255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Monica N., Meriam C., Racaniello V. R. Mapping of sequences required for mouse neurovirulence of poliovirus type 2 Lansing. J Virol. 1986 Feb;57(2):515–525. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.515-525.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liprandi F. Isolation of plaque variants differing in virulence from the 17D strain of yellow fever virus. J Gen Virol. 1981 Oct;56(Pt 2):363–370. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-56-2-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monath T. P., Kinney R. M., Schlesinger J. J., Brandriss M. W., Brès P. Ontogeny of yellow fever 17D vaccine: RNA oligonucleotide fingerprint and monoclonal antibody analyses of vaccines produced world-wide. J Gen Virol. 1983 Mar;64(Pt 3):627–637. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-3-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omata T., Kohara M., Kuge S., Komatsu T., Abe S., Semler B. L., Kameda A., Itoh H., Arita M., Wimmer E. Genetic analysis of the attenuation phenotype of poliovirus type 1. J Virol. 1986 May;58(2):348–358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.2.348-358.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvin J. D., Moscona A., Pan W. T., Leider J. M., Palese P. Measurement of the mutation rates of animal viruses: influenza A virus and poliovirus type 1. J Virol. 1986 Aug;59(2):377–383. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.377-383.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racaniello V. R., Baltimore D. Cloned poliovirus complementary DNA is infectious in mammalian cells. Science. 1981 Nov 20;214(4523):916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.6272391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repik P. M., Dalrymple J. M., Brandt W. E., McCown J. M., Russell P. K. RNA fingerprinting as a method for distinguishing dengue 1 virus strains. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983 May;32(3):577–589. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C. M., Lenches E. M., Eddy S. R., Shin S. J., Sheets R. L., Strauss J. H. Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution. Science. 1985 Aug 23;229(4715):726–733. doi: 10.1126/science.4023707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger J. J., Brandriss M. W., Monath T. P. Monoclonal antibodies distinguish between wild and vaccine strains of yellow fever virus by neutralization, hemagglutination inhibition, and immune precipitation of the virus envelope protein. Virology. 1983 Feb;125(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. R., Calvo J. M. Nucleotide sequence of the E coli gene coding for dihydrofolate reductase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980 May 24;8(10):2255–2274. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.10.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer D. A., Holland J. J. Direct method for quantitation of extreme polymerase error frequencies at selected single base sites in viral RNA. J Virol. 1986 Jan;57(1):219–228. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.1.219-228.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E. G., Rice C. M., Strauss J. H. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of Sindbis virus. Virology. 1984 Feb;133(1):92–110. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi T., Palmieri M., Weissmann C. QB DNA-containing hybrid plasmids giving rise to QB phage formation in the bacterial host. Nature. 1978 Jul 20;274(5668):223–228. doi: 10.1038/274223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler M., Anderson C. R. The relative resistance of dengue-immune monkeys to yellow fever virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1975 Jan;24(1):115–117. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengler G., Castle E., Leidner U., Nowak T., Wengler G. Sequence analysis of the membrane protein V3 of the flavivirus West Nile virus and of its gene. Virology. 1985 Dec;147(2):264–274. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]