Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the dietary and activity correlates of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption in middle and high-school children.

METHODS

Data were obtained from a cross-sectional survey of 15,283 middle and high school children in Texas, USA. Consumption of sodas and consumption of non-carbonated flavored and sports beverages (FSB) were examined separately for their associations with level of (a) unhealthy foods (fried meats, fries, desserts) and (b) healthy foods (vegetables, fruit, and milk) (c) physical activity including usual vigorous physical activity, and participation in organized physical activity, and (d) sedentary activity, including hours spent on TV, the computer, and videogames.

RESULTS

In both sexes, consumption of soda and FSB were systematically associated with a number of unhealthy dietary practices, as well as with sedentary behaviors. However, consumption of flavored and sports beverages showed significant positive graded associations with several healthy dietary practices and level of physical activity, while soda consumption showed no such associations with healthy behaviors.

CONCLUSIONS

Consumption of flavored and sports beverages coexists with healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors, suggesting popular misperception of these beverages as consistent with a healthy lifestyle. Assessment and obesity-prevention efforts targeting SSB need to distinguish between flavored and sports beverages from sodas.

Keywords: Soft drinks, Correlation, Dietary habits, Physical activity, Population-based studies

Despite recent reports of a possible slowdown in the obesity epidemic, the obesity burden in the United States remains a troubling public health issue1, 2. Currently, nearly 17% of children and adolescents (age 2–19) in the US are at or above the 95th percentile of the 2000 BMI-for-age CDC growth charts2. These trends have spurred intensive efforts to identify effective strategies for preventing weight gain among adolescents. Consistent with the multi-factorial nature of obesity causation3, these interventions encompass a variety of dietary and activity behaviors that are believed to affect energy balance, and hence weight gain 4–8.

One target behavior of interest for interventions is the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). Although sodas (carbonated beverages) are usually seen as the primary SSBs, the category also includes sports drinks and a large number of colas and fruit-flavored beverages which are not carbonated, but nevertheless contain large amounts of added sugar. The consumption of both types of SSBs by children has increased dramatically in the past few decades. Between 1977 and 1998, the prevalence of daily SSB consumption among children aged 11–18 years nearly tripled9, while the amount of SSB intake per day in this population more than doubled10. Adolescents now derive 10–15% of their total caloric intake from the consumption of SSB11. Because these increases have occurred concomitantly with rising levels of childhood overweight and obesity across the population, several scholars theorize that SSB consumption may be an important driver of the obesity epidemic12, 13. Several individual-level cross-sectional and cohort studies confirm an association between soft drink consumption and BMI or weight gain14, 15.

Nevertheless, only a small number of interventions have explicitly targeted SSB consumption as a primary outcome16. SSB interventions that have been successful tend to be characterized by environmental alterations, such as home delivery of non-caloric beverages to displace SSBs17, or the installation of water fountains in schools18. There is a need to develop more feasible behaviorally-based interventions. An important knowledge gap in this regard is the absence of information regarding the behavioral context of SSB consumption among adolescents. Little is known about the dietary and activity correlates of SSB consumption, and whether these behavioral correlates are similar across different categories of SSBs in this age-group. Several studies have reported that SSBs displace milk consumption19, 20 and one small study showed reduced fruit consumption and increased calorie consumption associated with high levels of SSB consumption21, but apart from these data, little is known about foods that are either complementary to or negatively associated with SSB consumption. Similarly, there is little published work examining if SSB consumption is associated with specific patterns of physical and/or sedentary activity. Knowledge of dietary and activity correlates, and how they differ across broad subgroups of beverages, is clearly relevant in informing the design of broad-based behavioral interventions targeting SSB consumption among adolescents.

The primary purpose of this study is to examine the dietary and activity correlates of SSB consumption among adolescents. Data for the study are obtained from the School Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN) surveys conducted by the University of Texas School of Public Health and funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services in the state of Texas in 2004–200522. The size of the dataset (n=15,283), the substantial representation of key racial and ethnic categories, and the age groups represented (8th and 11th grade) all make these data particularly suited to these analyses.

We hypothesized that SSB consumption co-occurs with specific dietary and activity behaviors for children at these ages, such that the extent of each of these behaviors would vary systematically across levels of SSB consumption. We further presumed that these behaviors vary by gender, as a number of studies have shown sex differences in the level of SSB consumption as well as in possibly associated dietary behaviors23–25. Finally, we hypothesized that the behavioral correlates of SSB consumption vary with the type of SSB consumed, specifically, regular sodas and flavored and sports beverages (FSB), because of differences in how consumers perceive these two categories. The analysis is limited to 8th and 11th grade children as younger children typically have lower control over the acquisition of beverages or the context of beverage consumption.

METHODS

The SPAN project is a surveillance system designed to monitor childhood obesity and related behaviors in school children at the state level. The cross-sectional study design utilized a stratified, multistage probability sampling scheme to obtain data, and was designed to be representative at the state level and by 3 major ethnic groups: African American, Hispanic, and white/other. Questionnaires were used to collect self-reported data on students’ eating behaviors on the previous day, using a food frequency questionnaire approach. Usual physical activity and sedentary activity were assessed through self-report. Versions of these questionnaires have been previously evaluated for reproducibility and validity26. The sampling frame for SPAN 2004–2005 included 87% of public school children in Texas. In all, 160 secondary schools were sampled. Further details of the SPAN study design are available elsewhere22. Analyses for this paper are limited to 15,283 8th and 11th grade students represented in SPAN 2004–2005 data, the most recent year for which complete statewide data are available. Approval for the SPAN study was obtained from the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston as well as the Texas Department of State Health Services Institutional Review Board and participating school districts.

Sugar-sweetened beverages

Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (SSB) are drinks that contain added caloric sweeteners, such as sugar or high-fructose corn syrup13. The definition includes a large variety of both carbonated and non-carbonated drinks, and excludes 100% fruit juice. Consistent with our hypothesis that sodas are perceived as a beverage type distinct from sports drinks and flavored beverages, we operationalize SSB consumption as three distinct measures: consumption of regular (not diet) sodas, consumption of noncarbonated flavored and sports beverages (FSB), and consumption of any SSB (obtained as the sum of responses for regular soda and FSB). The question relating to soda consumption is asked as follows: “Yesterday, how many times did you drink any regular (not diet) sodas or soft drinks?”, while the wording for question for FSB is as follows: “Yesterday, how many times did you drink any punch, Kool-Aid®, sports drinks, or other fruit-flavored drinks? Do not count 100% fruit juice.” Responses to each of these measures, obtained as number of servings consumed on the previous day, were available in one of four ordinal categories: none, one, two, and three or more. Both categorical and continuous specifications of beverage consumption were employed in the analyses. Prevalence of SSB consumption, as well as amount of beverage consumed, were both derived from these measures. Consumption of 100% fruit juice was also examined for its associations with the behavioral measures of interest, as fruit juice has been linked to adiposity in some studies27.

Dietary measures

Dietary correlates were drawn from 22 detailed questions included on SPAN 2004–2005, which referenced specific marker foods or food groups. As in the beverage questions, these questions pertained to number of times the food was consumed on the previous day, and responses ranged from none (0) to three or more. For the analysis of dietary behaviors, items were examined singly or in combination to yield a set of healthy and unhealthy foods/food groups, as well as alternative beverage choices. The unhealthy food groups examined included (a) consumption of fried meats (obtained as a sum of two related items - hamburgers and related meats, and fried meats); (b) fried snacks (a single item referencing French fries, chips, and other savory chip-type snacks); and (c) desserts, obtained as the sum of three items (frozen desserts, cakes, chocolate /candy). Healthy food and beverage groups included (a) fruit (b) vegetables and (c) milk. Each of the individual food item scores ranged from 0–3, except fried meats (0–6) and desserts (0–9). Means of items for each category of SSB consumption, as well for SSB consumption overall, were estimated from adjusted regression models.

Activity measures

Physical activity and sedentary activity behaviors were examined for their association with SSB beverage consumption. Physical activity measures included (a) number of days in the past week that the student engaged in vigorous physical activity, (b) whether the student opts for PE class and (c) whether the student participates in any organized physical activity, including participating in a sports team. The three sedentary activity measures included typical daily hours spent watching TV, typical hours per day spent on the computer, and typical hours per day on videogames. As in the case of dietary items, means for these measures were estimated across categories of SSB consumption.

Socio-demographic data

Demographic data included sex; grade (8th or 11th); language spoken at home (English or non-English); a school-level SES variable, defined as the proportion of enrolled students who were eligible for free or reduced meals, or were otherwise classified as economically disadvantaged, and self-identified race/ethnicity, collapsed into 3 major categories of interest, African-American, Hispanic, and all other races, largely comprising Whites). BMI measures were also utilized.

Statistical analyses

First we examined how the consumption of soda, flavored and sports beverages, and total SSB is distributed by gender, and across categories of potential confounders including race/ethnicity, socio-economic status (SES), grade-level and BMI. Means, standard errors, and proportions of beverage consumption in each demographic category were estimated. Next, in multivariate analyses, we estimated the degree of various dietary and activity behaviors across categories of beverage consumption for each of the beverage categories of interest, using linear regression models. Adjustment variables included race/ethnicity, grade, % economically disadvantaged, BMI, and language spoken at home. P-value for linear trend across increasing categories of beverage consumption was estimated for each outcome using identical regression models but with a continuous specification for the main beverage variable. All regression models were stratified by gender. An additional set of analyses similarly examined the associations of dietary and activity behaviors with 100% juice consumption. A level of .05 was established a priori as the threshold for statistical significance. All estimates and statistical tests took into account sampling stratification and clustering, and sample weights utilized by the survey. Estimates were obtained using Stata (version 11.0).

RESULTS

Detailed demographics of the sample by gender are presented in Table 1. The final sample consists of 7,573 males and 7,748 females. 58% of the children were from 8th grade (n=8,827). The racial/ethnic makeup of the sample was 42.9% Hispanic, 11.4% African-American, and the remaining 45.7% composed of mostly Caucasian children. About 22% of children reported that English was not the language used at home / with parents. Distributions of grade race/ ethnicity, language spoken at home, economic disadvantage were comparable across the sexes. The mean age of the sample was nearly 15 years (SD=1.6). 22% of the boys were obese (BMI>=30), and 17% of the girls in the sample were obese. 62% of the sample was normal weight (BMI<25). Across schools, the percent of economically disadvantaged students was approximately 50%.

TABLE 1.

Mean number of times sodas and flavored and sports beverages are consumed daily (based on previous day consumption) among 8th and 11th grade students across socio-demographic characteristics and BMI categories, by gender, SPAN 2004–2005

| Socio-demographic characteristics | MALES | FEMALES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular sodas | Flavored and sports beverage | Any SSB | Regular sodas | Flavored and sports beverage | Any SSB | |||

| n | Mean (SE)1) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |

| Total3 | 7,535 | 1.04 (0.05) | 1 (0.05) | 1.78 (0.05) | 7,748 | 0.85 (0.04) | 0.75 (0.04) | 1.46 (0.04) |

| Grade | ||||||||

| 8th | 4,328 (57%) | 0.97 (0.06) | 1.01 (0.06) | 1.73 (0.06) | 4,499 (58%) | 0.85 (0.06) | 0.82 (0.05) | 1.5 (0.06) |

| 11th | 3,207 (43%) | 1.13 (0.07) | 0.99 (0.06) | 1.85 (0.07) | 3,249 (42%) | 0.84 (0.06) | 0.66 (0.04) | 1.4 (0.06) |

| Race /ethnicity | ||||||||

| African- American | 795 (11%) | 0.82 (0.1) | 1.42 (0.08) | 1.92 (0.09) | 947 (12%) | 0.7 (0.07) | 1.21 (0.07) | 1.69 (0.07) |

| Hispanic | 3,128 (42%) | 1.05 (0.04) | 0.97 (0.03) | 1.8 (0.04) | 3,430 (44%) | 0.99 (0.05) | 0.7 (0.05) | 1.52 (0.05) |

| White / other | 3,612 (48%) | 1.1 (0.09) | 0.91 (0.08) | 1.72 (0.1) | 3,371 (44%) | 0.78 (0.06) | 0.64 (0.05) | 1.33 (0.06) |

| Language spoken at home | ||||||||

| Not English | 1,624 (22%) | 0.95 (0.05) | 0.86 (0.06) | 1.64 (0.06) | 1,688 (22%) | 1.01 (0.07) | 0.78 (0.04) | 1.58 (0.06) |

| English | 5,826 (77%) | 1.07 (0.06) | 1.05 (0.05) | 1.82 (0.06) | 5,957 (77%) | 0.8 (0.04) | 0.74 (0.04) | 1.42 (0.05) |

| Economic disadvantage tertiles | ||||||||

| Lowest tertile | 2,394 (32%) | 1 (0.11) | 0.92 (0.08) | 1.69 (0.1) | 2,371 (31%) | 0.72 (0.06) | 0.64 (0.04) | 1.26 (0.06) |

| Middle tertile | 2,591 (34%) | 1.11 (0.07) | 1.06 (0.05) | 1.88 (0.06) | 2,683 (35%) | 0.88 (0.05) | 0.73 (0.05) | 1.5 (0.05) |

| Upper tertile | 2,550 (34%) | 1.01 (0.05) | 1.03 (0.08) | 1.77 (0.06) | 2,694 (35%) | 0.96 (0.09) | 0.89 (0.07) | 1.63 (0.06) |

| BMI categories2 | ||||||||

| Normal | 4,540 (60%) | 1.09 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.06) | 1.82 (0.07) | 4,977 (64%) | 0.9 (0.05) | 0.75 (0.04) | 1.49 (0.06) |

| Overweight | 1,286 (17%) | 0.94 (0.06) | 0.9 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.11) | 1,471 (19%) | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.79 (0.07) | 1.41 (0.09) |

| Obese | 1,709 (23%) | 0.97 (0.06) | 0.99 (0.07) | 1.73 (0.09) | 1,300 (17%) | 0.74 (0.06) | 0.71 (0.05) | 1.36 (0.08) |

SE=Standard error.

Classification of BMI categories - normal=<85th percentile; overweight=85th to 95th percentile; obese= >=95th percentile - follows WHO guidelines.

Sample sizes are not weighted. Estimated means and standard errors take into account the complex sampling scheme and survey weights

Socio-demographic characteristics and amount of SSB consumption

Table 1 also presents the mean number of times SSBs were consumed (based on previous day self-reported consumption) across socio-demographic characteristics within gender and SSB categories. Among males, the average number of times soda is consumed daily increases from 8th grade to 11th grade, while the number of times FSBs are consumed remains steady. In contrast, among females, soda consumption remains steady from 8th to 11th grade, and FSB consumption declines substantially. Marked differences in average consumption are also present across racial/ethnic categories. African-American children of both sexes have lower soda consumption but considerably higher FSB consumption than either Hispanic or White/Other children. Among males, children who reported that English was not the primary language used at home have lower soda and FSB consumption than children for whom English is the primary language at home. The reverse is true among females. Soda and FSB consumption increase with economic disadvantage among females. Soda or FSB consumption show no patterning by BMI level.

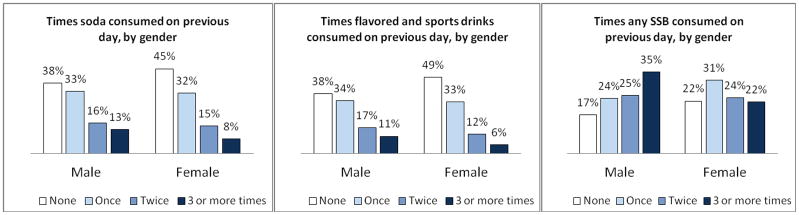

Prevalence and level of beverage consumption by sex and type of SSB

Prevalence of SSB consumption (defined here as the proportion of students reporting any consumption of SSB on the previous day) and level of consumption vary by sex, and by type of SSB (Figure 1). Males report both higher prevalence and higher levels of consumption of soda and of FSB, with 62% of males reporting that they drank regular soda one or more times, and a similar proportion reporting that they drank FSB one or more times the previous day, compared to 55% and 51% respectively of females. The prevalence of consumption of any SSB is substantially larger in both males and females (83% and 78% respectively), suggesting that consumption of sodas and FSBs appear to be independent behaviors and therefore additive across categories. Large proportions of both males and females (35% and 22%) report consuming some SSB three or more times a day.

Figure 1.

Previous day consumption of soda, flavored and sports beverages, and any SSB by Texas middle and high school boys and girls, SPAN 2004–2005.

Dietary behaviors associated with beverage consumption

Associations of ‘unhealthy’ foods (meats, fried snacks, desserts) with sodas, FSB and overall SSB are unequivocally positive for males and females (Table 2). Consumption of each of these items increases significantly with level of consumption of these categories of SSB. With the ‘healthy foods’–vegetables and fruit, the picture is not as clear-cut and varies with the type of SSB. Thus, vegetable and fruit consumption increase with level of FSB consumption, but decrease with level of soda consumption. These trends are apparent with both males and females, and are statistically significant in the case of females. Interestingly, these opposite associations with sodas and FSB result in an apparent lack of association with the composite SSB variable. Apparent displacement of milk by soda consumption is seen in both males and females, but FSB consumption, in contrast, is positively associated with milk consumption. In general, the results suggest that soda consumption is associated with lower consumption of healthy foods, but FSB consumption increases concomitantly with the consumption of healthy foods, especially among girls.

Table 2.

Association of level of SSB consumption with healthy and unhealthy diet measures

| Unhealthy meats | Fries | Desserts | Vegetables | Whole Fruit | Milk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Males |

||||||

| Times consumed |

Soda |

|||||

| 0 | 1.32 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 1.48 |

| 1 | 1.36 | 0.99 | 1.31 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1.33 |

| 2 | 1.52 | 0.95 | 1.39 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 1.27 |

| 3 or more | 1.89 | 1.27 | 2.08 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.18 |

| p for trend | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.053 | 0.374 | 0.013 ↓ |

| Times consumed |

Flavored and sports beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 1.29 | 0.79 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 1.35 |

| 1 | 1.42 | 0.93 | 1.36 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 1.38 |

| 2 | 1.63 | 1.04 | 1.53 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 1.24 |

| 3 or more | 1.74 | 1.23 | 2.15 | 1.05 | 1.20 | 1.49 |

| p for trend | 0.001 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.150 | 0.000 ↑ | 0.731 |

| Times consumed |

Any sugar-sweetened beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 1.15 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 1.48 |

| 1 | 1.33 | 0.76 | 1.14 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 1.39 |

| 2 | 1.39 | 0.95 | 1.20 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 1.38 |

| 3 or more | 1.67 | 1.15 | 1.82 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 1.26 |

| p for trend | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.612 | 0.105 | 0.222 |

|

Females |

||||||

| Times consumed |

Soda |

|||||

| 0 | 1.08 | 0.80 | 1.20 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 1.10 |

| 1 | 1.24 | 0.90 | 1.30 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.97 |

| 2 | 1.41 | 1.18 | 1.66 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.87 |

| 3 or more | 1.68 | 1.32 | 1.83 | 0.54 | 0.80 | 0.97 |

| p for trend | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↓ | 0.010 ↓ | 0.003 ↓ |

| Times consumed |

Flavored and sports beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 1.18 | 0.82 | 1.15 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.20 | 0.93 | 1.39 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.95 |

| 2 | 1.28 | 1.14 | 1.57 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 1.14 |

| 3 or more | 1.63 | 1.37 | 2.38 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.28 |

| p for trend | 0.021 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.039 ↑ | 0.040 ↑ | 0.044 ↑ |

| Times consumed |

Any sugar-sweetened beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 1.10 | 0.72 | 1.15 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 1.12 |

| 1 | 1.10 | 0.84 | 1.16 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.96 |

| 2 | 1.29 | 0.95 | 1.33 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 1.02 |

| 3 or more | 1.48 | 1.24 | 1.87 | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.97 |

| p for trend | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.015 ↓ | 0.103 | 0.185 |

Estimates are obtained from linear regression models that estimate the mean number of times each food group was consumed daily, by ordered levels of SSB consumption. All models are adjusted for grade, race/ethnicity, language spoken at home, and socioeconomic status, and are stratified by sex. Models take into account the complex sampling design of the study and survey weights. p for linear trend is obtained from regression models that use a continuous specification of the beverage variable. Arrows are used to indicate the direction of significant (p<=.05) trends.

Physical and sedentary activity behaviors associated with beverage consumption

Again, it is evident from the analysis that soda and FSB consumption relate differently to physical and sedentary activity (Table 3). Each of the three physical activity indexes examined (amount of vigorous physical activity, participation in school PE classes, and participation in organized sports activity) decreases with level of soda consumption and increases with level of FSB consumption, especially among boys. Positive associations with FSB consumption are repeated among girls, but not the negative associations with soda consumption. Finally, each of the three sedentary activity measures (hours spent watching TV, on the computer, and with video games) increase in general with both soda consumption and with FSB consumption among both girls and boys, although associations tend to be significant mostly with soda consumption.

Table 3.

Association of level of SSB consumption with physical and sedentary activity

| Days VPA | Opts for PE class | Any organized PA | Hours watched TV | Hours on computer | Hours on video | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Males |

||||||

| Times consumed |

Soda |

|||||

| 0 | 4.90 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 2.47 | 1.30 | 1.37 |

| 1 | 4.33 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 2.64 | 1.30 | 1.58 |

| 2 | 4.28 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 2.77 | 1.57 | 1.84 |

| 3 or more | 4.48 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 3.25 | 1.47 | 2.02 |

| p for trend | 0.008 ↓ | 0.096 | 0.008 ↓ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.015 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ |

| Times consumed |

Flavored and sports beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 4.38 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 2.69 | 1.36 | 1.60 |

| 1 | 4.43 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 2.56 | 1.28 | 1.55 |

| 2 | 4.80 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 2.67 | 1.49 | 1.43 |

| 3 or more | 5.18 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 2.97 | 1.47 | 1.99 |

| p for trend | 0.005 ↑ | 0.006 ↑ | 0.044 ↑ | 0.148 | 0.362 | 0.220 |

| Times consumed |

Any sugar-sweetened beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 4.81 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 2.38 | 1.34 | 1.36 |

| 1 | 4.39 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 2.66 | 1.23 | 1.55 |

| 2 | 4.47 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 2.51 | 1.25 | 1.41 |

| 3 or more | 4.60 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 2.94 | 1.56 | 1.88 |

| p for trend | 0.816 | 0.219 | 0.616 | 0.000 ↑ | 0.019 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ |

|

Females |

||||||

| Times consumed |

Soda |

|||||

| 0 | 3.94 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 2.39 | 1.11 | 0.26 |

| 1 | 3.55 | 0.50 | 0.69 | 2.67 | 1.45 | 0.34 |

| 2 | 3.50 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 2.93 | 1.54 | 0.34 |

| 3 or more | 3.33 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 3.30 | 1.50 | 0.55 |

| p for trend | 0.002 ↓ | 0.400 | 0.001 ↓ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ | 0.003 ↑ |

| Times consumed |

Flavored and sports beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 3.58 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 2.54 | 1.28 | 0.28 |

| 1 | 3.75 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 2.67 | 1.38 | 0.32 |

| 2 | 3.93 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 2.66 | 1.16 | 0.25 |

| 3 or more | 4.09 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 3.25 | 1.60 | 0.79 |

| p for trend | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.093 ↑ | 0.007 ↑ | 0.389 | 0.005 ↑ |

| Times consumed |

Any sugar-sweetened beverage |

|||||

| 0 | 4.02 | 0.56 | 0.75 | 2.33 | 1.20 | 0.21 |

| 1 | 3.50 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 2.52 | 1.17 | 0.30 |

| 2 | 3.70 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 2.67 | 1.41 | 0.35 |

| 3 or more | 3.68 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 3.08 | 1.56 | 0.42 |

| p for trend | 0.307 | 0.818 | 0.354 | 0.000 ↑ | 0.005 ↑ | 0.000 ↑ |

Estimates are obtained from linear regression models that estimate the level of physical and sedentary activity for ordered levels of SSB consumption. All models are adjusted for grade, race/ethnicity, language spoken at home, and socioeconomic status, and are stratified by sex. Models take into account the complex sampling design of the study. p for linear trend is obtained from regression models that use a continuous specification of the beverage variable. Arrows are used to indicate the direction of significant (p<=.05) trends.

Additional analyses examined the associations of these behaviors with 100% juice consumption (results not shown). Correlates of 100% juice consumption are very similar to those seen with FSB consumption, with fruit juice consumption showing positive associations with physical activity measures and healthy food consumption, as well as with unhealthy food practices and sedentary behavior.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis, we examined the dietary and activity correlates of SSB consumption among girls and boys from a population based sample of 8th and 11th grade children in Texas. The analysis included an examination of the prevalence and levels of consumption of two major types of SSB (regular sodas, and flavored and sports beverages), by gender and across various socio-demographic characteristics.

Several findings are noteworthy. First, when total SSB (both regular sodas and flavored and sports beverages) is considered, the prevalence of SSB consumption among these children is very high, with 28% of children consuming three or more SSBs a day. Second, the amount of SSB consumption varies by socio-demographic characteristics as well as by type of SSB. Third, the study is the first to demonstrate pronounced and consistent associations of a variety of dietary and activity behaviors with the level of SSB consumption. Fourth, these associations vary substantially and systematically by the type of beverage considered.

The high level of consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among adolescents has generated considerable concern because of its potential to increase weight gain. It has been estimated that daily consumption of just 1 12 oz. can of soda or other SSB could lead to as much as 15-lb weight gain in a year28. In light of this, our findings relating to the high prevalence and level of soda and other SSB consumption among 8th and 11th grade children are troubling. Approximately 10% of these children report consuming three or more sodas on the previous day. Average consumption of SSBs across all children is about 1.6 servings per day; this is likely an underestimate, as the questions relating to consumption were top-coded at 3, and do not include other beverages such as energy drinks or sweetened milk drinks, which frequently contain high levels of sugar.

The findings relating to differences in level of consumption by socio-demographic category have important implications for the development of interventions. Boys consume higher levels of SSB than girls, and soda consumption in particular increases with grade level among boys. African-Americans consume soda at lower levels than Hispanics or Whites, but their level of FSB consumption is substantially higher. Soda consumption increases with economic disadvantage among females, but less so among males. Different patterns of SSB consumption among different demographic subgroups, especially across racial/ethnic categories, can and should be accommodated in efforts to tailor interventions.

Our most important findings relate to the difference in behavioral correlates of FSB and soda consumption. Both soda consumption and FSB consumption are positively associated with various unhealthy dietary practices and sedentary behaviors, suggesting that these practices may be universal in the adolescent population. However, there is clear divergence between the two categories of SSBs with regard to the consumption of healthy items, such as milk, fruit and vegetables, with FSB showing a positive association and sodas showing a negative association. Similarly, physical activity increases with level of FSB consumption but decreases with level of soda consumption. The most likely explanation for these findings is that FSBs have been successfully marketed as beverages consistent with a healthy lifestyle, to set them apart from sodas. Often, these beverages contain a minimal percentage of fruit juice, or more commonly, contain artificial fruit flavors, conveying the impression that the drink is more healthful than it actually is. This may explain our finding that the behavioral correlates of FSB consumption are very similar to those of fruit juice consumption, while remaining distinct from the correlates of soda consumption. Thus, it is apparent that consumers differentiate between sodas and the sports and flavored drink groups. This product differentiation between sodas and FSB has not been made by public health advocates and scholars, who focus instead on the fact that all these beverages are sugar-sweetened13, 15, 29. While this approach is consistent from a physiological point of view, our findings clearly underscore its inadequacy as a paradigm for informing analyses as well as the development of interventions. Analyses that examine sugar-sweetened beverages as a single category mask the differential behavioral associations with categories of SSB. Recognition of the different behavioral contexts of different categories of SSB needs to be an important input in intervention design, as well as in assessment of SSB consumption.

This study does have limitations. The associations are cross-sectional, and provide no information on the direction of causality. Our instruments for measuring both beverage consumption and behavioral correlates are blunt, given that there are only 4 response categories for most items, and that the measures are derived from self-report. Despite adjustment for several covariates, there may be some residual confounding from unmeasured variables. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the findings are an artifact, given the large size of the dataset, and the similarity of the results across conceptually consistent categories. In conclusion, this study describes novel findings relating to the behavioral correlates of SSB consumption that may be important for intervention design.

Abbreviations

- SSB

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- FSB

Flavored and sports beverages

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- SPAN

School Physical Activity and Nutrition

- PE

Physical Education

- VPA

Vigorous Physical Activity

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: None

Conflict of interest declarations: None

Contributor Information

Nalini Ranjit, UT School of Public Health (Austin Regional Campus) and the Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living

Martin H. Evans, UT School of Public Health (Austin Regional Campus)

Courtney Byrd-Williams, UT School of Public Health (Austin Regional Campus) and the Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living

Alexandra E. Evans, UT School of Public Health (Austin Regional Campus) and the Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living.

Deanna M. Hoelscher, UT School of Public Health (Austin Regional Campus) and the Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High Body Mass Index for Age Among US Children and Adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008;299:2401–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of High Body Mass Index in US Children and Adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM. Multifactorial causation of obesity: implications for prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:563S–572. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.3.563S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nader PR, Stone EJ, Lytle LA, et al. Three-Year Maintenance of Improved Diet and Physical Activity: The CATCH Cohort. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:695–704. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan P, Rex J. New Moves: a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Prev Med. 2003;37:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoelscher D, Springer A, Ranjit N, et al. Reductions in Child Obesity Among Disadvantaged School Children With Community Involvement: The Travis County CATCH Trial. Obesity. 2010;18:S36–S44. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, et al. Reducing Obesity via a School-Based Interdisciplinary Intervention Among Youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:409–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grey M, Berry D, Davidson M, Galasso P, Gustafson E, Melkus G. Preliminary Testing of a Program to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes Among High-Risk Youth. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavadini C, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. US adolescent food intake trends from 1965 to 1996. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:18–24. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.French S, Lin B, Guthrie J. National trends in soft drink consumption among children and adolescents age 6 to 17 years: Prevalence, amounts, and sources, 1977/1978 to 1994/1998. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103:1326–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)01076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1604–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity.[see comment][erratum appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Oct;80(4):1090] American Journalof Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:537–43. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brownell KD, Frieden TR. Ounces of prevention--the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:1805–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84:274–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of Soft Drink Consumption on Nutrition and Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J PublicHealth. 2007;97:667–675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. Research to Practices Series No. 3. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity; 2006. Does Drinking Beverages with Added Sugars Increase the Risk of Overweight? [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK, Chomitz VR, Ellenbogen SJ, Ludwig DS. Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:673–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muckelbauer R, Libuda L, Clausen K, Toschke AM, Reinehr T, Kersting M. Promotion and Provision of Drinking Water in Schools for Overweight Prevention: Randomized, Controlled Cluster Trial. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e661–667. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller KL, Kirzner J, Pietrobelli A, St-Onge M-P, Faith MS. Increased sweetened beverage intake is associated with reduced milk and calcium intake in 3-to 7-year-old children at multi-item laboratory lunches. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Striegel-Moore RH, Thompson D, Affenito SG, et al. Correlates of beverage intake in adolescent girls: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. [see comment] Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;148:183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen KW, Ash DM, Warneke C, de Moor C. Intake of soft drinks, fruit-flavored beverages, and fruits and vegetables by children in grades 4 through 6. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1475–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoelscher D, Day R, Lee E, et al. Measuring the prevalence of overweight in Texas schoolchildren. AmJ Public Health. 2004;94:1002–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harnack L, Stang J, Story M. Soft drink consumption among US children and adolescents: nutritional consequences. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99:436–41. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Temple JL, Bulkley AM, Briatico L, Dewey AM. Sex differences in reinforcing value of caffeinated beverages in adolescents. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20:731–741. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328333b27c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardle J, Haase A, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisie F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:107–116. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoelscher D, Day R, Kelder S, Ward J. Reproducibility and validity of the secondary level School-Based Nutrition Monitoring student questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103:186–194. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faith MS, Dennison BA, Edmunds LS, Stratton HH. Fruit Juice Intake Predicts Increased Adiposity Gain in Children From Low-Income Families: Weight Status-by-Environment Interaction. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2066–2075. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apovian CM. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2004;292:978–979. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drewnowski A, Bellisle F. Liquid calories, sugar, and body weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85:651–661. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]