Abstract

Background

Around the world, health professionals and program managers are leading and managing public and private health organizations with little or no formal management and leadership training and experience.

Objective

To describe an innovative 2-year, long-term apprenticeship Fellowship training program implemented by Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) to strengthen capacity for leadership and management of HIV/AIDS programs in Uganda.

Implementation process

The program, which began in 2002, is a 2-year, full-time, non-degree Fellowship. It is open to Ugandan nationals with postgraduate training in health-related disciplines. Enrolled Fellows are attached to host institutions implementing HIV/AIDS programs and placed under the supervision of host institution and academic mentors. Fellows spend 75% of their apprenticeship at the host institutions while the remaining 25% is dedicated to didactic short courses conducted at MakSPH to enhance their knowledge base.

Achievements

Overall, 77 Fellows have been enrolled since 2002. Of the 57 Fellows who were admitted between 2002 and 2008, 94.7% (54) completed the Fellowship successfully and 50 (92.3%) are employed in senior leadership and management positions in Uganda and internationally. Eighty-eight percent of those employed (44/54) work in institutions registered in Uganda, indicating a high level of in-country retention. Nineteen of the 20 Fellows who were admitted between 2009 and 2010 are still undergoing training. A total of 67 institutions have hosted Fellows since 2002. The host institutions have benefited through staff training and technical expertise from the Fellows as well as through grant support to Fellows to develop and implement innovative pilot projects. The success of the program hinges on support from mentors, stakeholder involvement, and the hands-on approach employed in training.

Conclusion

The Fellowship Program offers a unique opportunity for hands-on training in HIV/AIDS program leadership and management for both Fellows and host institutions.

Keywords: building capacity, HIV/AIDS, program leadership, management, mentored Fellowship, Uganda

There is growing recognition that a shortage of health workers is among the most significant constraints in achieving the three health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): to reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, and combat HIV/AIDS and other diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria. The global problem of inadequate human resources for health is most acute in sub-Saharan Africa where the scope of the health workforce crisis is alarming (1). There is simply insufficient adequately trained human capacity, of all cadres, in the region to absorb, apply, and make efficient use of interventions being offered by many health initiatives (1). The most obvious response to human resource shortages is to train more. However, in many instances, much attention has been given to enhancing clinical and public health skills at the expense of management and leadership skills needed to strengthen health systems (2). As a result, many health professionals and program managers continue to lead and manage public and private health organizations and systems with little or no formal management and leadership education and experience (3). It is critical that program leaders and managers receive the necessary training in order to deliver effective and efficient interventions.

Traditional ways to effectively build capacity to lead change, such as sending an individual to an off-site workshop or course, are not only slow and costly but may disrupt service provision (4). Several strategies have been implemented in developing countries to address gaps in public health leadership and management. In Egypt, a leadership development program that aimed at improving health services by increasing managers’ ability to create high performing teams increased the number of new family planning visits in three districts by between 20–68% in just 1 year (4). In Liberia, a 6-month health systems management course resulted in substantial improvement in self-reported management skills (5). In Zimbabwe, a program aimed at increasing leadership capacity for HIV/AIDS programs registered significant increases in the number of public health professionals trained at a modest cost (6). The Zimbabwean program used new HIV/AIDS program-specific funds to build on the assets of a local training institution to strengthen and expand the general public health leadership capacity in the country (6).

In Uganda, Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH), with support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), introduced a Fellowship training program aimed at enhancing leadership and management capacity for HIV/AIDS programs. This program was initiated in 2002 and is still continuing. Its implementation has largely hinged on the principles of ‘learning by doing’ interspersed with mentorship opportunities provided to Fellows to enhance their competencies in program leadership and management.

Mentorship is a two-way mutually beneficial learning situation where the mentor provides advice, shares knowledge and experiences, and teaches using a low pressure, self-discovery approach (7). Healy and Welchert (8) defined mentorship as a dynamic, reciprocal relationship in a work environment between an advanced career incumbent (mentor) and a beginner (protégé), aimed at promoting the development of both. Mentorship helps the mentee to build their capacity as well as enhance their skills to produce the desired results (9). Mentorship has been recognized as a catalyst for career success, and mentoring relationships have been cited as important in facilitating career selection, advancement, and productivity (10, 11). A systematic review of mentorship and its relationship to career development found that respondents who had a mentor were more likely to allocate more time to research; they were more productive in research in terms of number of publications and grants and were more likely to complete their thesis (12). However, this approach has not been widely used in formal training in sub-Saharan Africa.

The purpose of this paper is to share our experiences in developing and implementing this apprenticeship program for enhancing individual and institutional capacity for leadership and management of HIV/AIDS programs in Uganda.

Implementation process

Setting

Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) is one of the four schools under Makerere University College of Health Sciences in Kampala, Uganda. The mission of the school is to improve the attainment of better health for the people of Uganda through public health training, research, and community service while its vision is to become a center of excellence by providing leadership in Public Health. MakSPH offers four Masters Programs, namely: Master of Public Health-full time (MPH), Master of Public Health-Distance Education (MPH-DE), Master of Public Health Nutrition (MPHN), and Master of Health Services Research (MHSR). As of July 2010, a total of 166 Masters’ students were enrolled at MakSPH; 104 for MPH-DE, 27 for MPH-full time, 17 for MPHN, and 13 for MHSR (13). Twenty-one PhD students are enrolled. MakSPH employs a total of 46 teaching staff.

Fellowship program overview

The main objective of the Fellowship program is to provide systematic public health training focused on increasing the number of professionals equipped with program leadership and management skills to implement HIV/AIDS programs, strengthen and/or replicate successful HIV/AIDS programs, as well as enhance the sustainability of HIV/AIDS programs in Uganda.

The long-term Fellowship is a 2-year, non-degree, full-time program. It is offered on a competitive basis to Ugandan nationals with postgraduate training in a health-related field such as Public Health, Medicine, Nursing, and other fields considered relevant to the fight against HIV/AIDS such as Statistics, Mass Communication, Social Sciences, Demography, or Information Technology. Training Fellows from diverse professional backgrounds is considered rational since mitigation of the HIV/AIDS problem requires a multi-disciplinary approach.

The long-term Fellowship is a hands-on apprenticeship program with the field component accounting for 75% of the 2 years. Twenty-five percent of the 2-year duration is dedicated to academic instruction comprising multi-disciplinary short courses conducted at the School of Public Health. The academic component is aimed at bolstering the Fellows’ knowledge base in leadership and management of HIV/AIDS programs as well as exposing them to the tools of public health such as epidemiology, biostatistics, and informatics. The field placement is to a host institution that is an HIV/AIDS program involved in service, care, prevention, information dissemination, or policy formulation in any part of Uganda.

Enrollment of Fellows

The enrollment of Fellows begins with solicitation of applications through the local print media and the program website. Short listed candidates are interviewed and selection of Fellows done based on the career path and leadership potential, previous involvement in HIV/AIDS programming, the Fellow's interests, and availability of institutions to accommodate these interests among other criteria. Up to 10 Fellows are selected annually.

Host institution selection

Host institutions are government or non-governmental organizations involved in service delivery in any part of Uganda. Host institution selection is done competitively based on the number of institutions applying to host Fellows, the availability of a Fellow who matches the interests of the host institution, and the proposed terms of reference for the Fellow. The terms of reference (TOR) specify the key assignments that will be allocated to the Fellow at the host institution and may differ from institution to institution. The TOR specifies the key outputs of the Fellow at specific intervals and the level of support that will be provided to the Fellow in achieving the set targets. Applications from host institutions also include a description of individuals who can serve as host mentors. Selected institutions benefit through the Fellows’ technical expertise, opportunity for host institution staff to attend short courses at MakSPH free of charge, as well as through grant support to Fellows to develop and implement a programmatic activity.

Placement of Fellows at host institutions

Upon enrollment, Fellows are introduced to the basics of program design, implementation, and evaluation in order to prepare them for field placement. Fellows are thereafter posted to the host institutions to begin their placement. While at the host institution, Fellows participate in a series of program leadership and management activities meant to enhance their capacity as well as professional growth. Fellows’ activities at the host institution are guided by the terms of reference they have agreed upon with the host institution mentor.

The Fellowship program provides grant support to Fellows to implement a ‘programmatic activity.’ The programmatic activity is any activity that the Fellow undertakes at the host institution in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Fellowship Program. The selection of the programmatic activity takes into consideration host institution priority needs and the Fellow's learning objectives. The Fellow develops a proposal describing the activity, its objectives, methods, and outcomes to the satisfaction of the host institution and the program. The implementation of the programmatic activity provides Fellows with hands-on experience in the design, implementation, evaluation, and reporting/dissemination of public health interventions. At the end of the Fellowship, Fellows disseminate their achievements and findings from their programmatic activities in a large workshop attended by stakeholders including the host institutions and other implementers and policy makers. This presentation and final report are requirements for completion of the training and award of a certificate of attendance from the program.

Mentorship

Mentorship under the Fellowship Program is accomplished through Fellows working closely with designated host and academic mentors. The academic mentor is a staff of the School of Public Health or one of the schools under the College of Health Sciences whose role is to facilitate, guide, and support the Fellow. The Academic Mentor guides the Fellow in report writing, preparation of scientific papers, and proposal writing among other roles.

The host mentor, on the other hand, is a member of staff at the host institution. The host institution mentor facilitates the Fellow's learning during field attachment by providing an enabling environment for the Fellow to share ideas and experiences as well as challenges him/her and the staff at the host institution. The host mentors are the main persons with whom the Fellow has day-to-day contact. The host mentor guides, supports, encourages, and supervises the Fellow during field attachment. He/she ensures that the Fellow is exposed to management and leadership experiences and challenges available at the host institution as well as other career growth opportunities. He/she assists the Fellow to fully integrate into the host institution.

In addition to academic and host mentors, Makerere University School of Public Health provides Fellows with ‘floating mentors’ in the areas of management, leadership, and advocacy as well as biostatistics. Floating mentors are persons with proven skills and long-standing experience in these fields. They are available to all Fellows with needs in these areas.

The Fellowship Program convenes one mentorship workshop per year to provide an opportunity for mentors and Fellows to learn about their roles as well as share their expectations. The workshop is normally held immediately after Fellows have reported to their host institutions to give them a chance to reconcile their own and their mentors’ expectations at an early stage.

Short courses

Participation in short courses accounts for 25% of the Fellowship time. Fellows attend a total of 29 short courses in 24 weeks during the Fellowship. The purpose of short courses is to facilitate the building of a strong knowledge base that can enable Fellows to acquire skills and competencies in the field. Short courses offered include: monitoring and evaluation of HIV/AIDS programs, continuous quality improvement, behavior change communication, strategic planning, operations research, human resource management, strategic leadership and management, and advocacy and resource mobilization strategies among others. These courses are drawn from those offered in the regular MAKSPH academic programs as well as those that cover current and priority issues in HIV/AIDS and program leadership and management. Some of these courses are offered before field attachment while others are offered at intervals during the apprenticeship training.

Evaluation of Fellows

The Fellowship program continuously monitors the Fellows’ progress and performs quarterly evaluation and documentation of their achievements based on their terms of reference. At the end of every quarter, academic and host mentors complete quarterly evaluation forms and indicate their assessment of the Fellows’ progress during the quarter. Mentors’ assessments are based on set criteria including the Fellows’ progress in terms of quantity and quality of work, punctuality of work, initiative, and creativity, commitment to program goals, team work, oral and written communication, planning and organization, problem-solving skills, professional skills development, growth in skills during the quarter, and responsiveness to supervision. These criteria are phrased in form of statements to which the mentors agree or disagree as part of the assessment. Examples of such statements include, ‘[Fellow] participates actively in identifying solutions to his/her learning objectives’ and ‘[Fellow] usually seeks, considers, and responds to supervisory guidance.’ The assessment is based on a scale of 1–5, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The quarterly evaluation is done during a face-to-face meeting that allows interaction and feedback to the Fellow.

In addition to academic and host mentors’ evaluations, Fellows complete their own evaluation forms to indicate their satisfaction with apprenticeship opportunities availed to them during the quarter and their level of satisfaction with the support received from mentors and the program. Fellows also prepare and submit quarterly reports indicating their achievements and challenges. The quarterly reports are reviewed by the academic and host mentors as well as program staff. Once all the evaluation forms and quarterly reports have been received, the program conducts an assessment of the Fellows’ progress using a checklist. Program staff and academic mentors conduct supervisory visits to support Fellows in accomplishing their host institution objectives. These meetings also provide an opportunity for feedback to the Fellows and institutions after the overall quarterly assessment by the program.

At the end of the 2-year apprenticeship, the Fellow's overall progress is determined as a function of: (1) the mentors’ evaluations over the 2-year period, (2) the Fellows’ evaluation of their own progress during the Fellowship, and (3) program assessment of the Fellows’ progress. A dissemination workshop is organized for Fellows to share their work and achievements at the host institution as well as receive Certificates of Attendance. In recognition of excellence, the best rated Fellow receives a ‘Matthew Lukwiya Award.’ This award is made in recognition of the outstanding leadership qualities, professional dedication, and selflessness exhibited by Dr Matthew Lukwiya (RIP), a physician then based at Lacor Hospital in Gulu district, Northern Uganda, who died while treating Ebola-infected patients in 2000.

Achievements

Enrollment since 2002

A total of 291 applications were received in relation to the long-term Fellowship Program between 2002 and 2010. Fifty-seven Fellows were admitted between 2002 and 2008; 54 (94.7%) of whom completed the Fellowship successfully. An additional 20 Fellows were admitted between 2009 and 2010; 19 (95%) of whom are continuing with the training. Overall, 77 Fellows have been admitted since 2002. Of the 77 Fellows, 33 (43%) were males while 44 (57%) were females. Three-quarters of those admitted were aged between 31 and 40 years. A total of 67 institutions have hosted Fellows since 2002, some of them for more than once. Of the 67 institutions, eight were based in rural Uganda (including two in western Uganda, three in southwestern Uganda, one in central Uganda, one in eastern Uganda, and one in West Nile). The majority of the institutions 59 were based in Kampala but many of them had programs in different parts of the country at the time of hosting Fellows.

Impact on Fellows

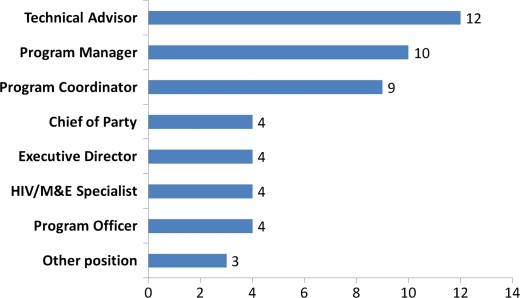

The Fellowship Program has had a positive impact in the career growth and enhancement of the professional status of Fellows. Graduate Fellows have taken up senior positions in national and international agencies. For many of the program graduates, there was a radical transformation from professionals employed in routine and mid-level positions to all-round program leaders and managers employed in senior positions within and outside Uganda. Of the 54 graduate Fellows, 50 (92.3%) are currently employed in senior leadership and management positions in Uganda and internationally, and of these, 44 (88%) are employed in institutions registered in Uganda, indicating a high level of in-country retention. Specifically, 12 Fellows are currently employed as Technical Advisors in leading health-related organizations in Uganda and internationally, 10 as Program Managers, 9 as Program Coordinators, 4 as Chief of Party, 4 as Executive Directors, 4 as HIV/AIDS/M&E Specialists, 4 as Program Officers, and 3 hold other positions including University Lecturer, Research Fellow, and Public Information Assistant (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Employment status of alumni Fellows enrolled between 2002 and 2008. Other positions include University Lecturer, Research Fellow, and Public Information Assistant.

The Fellowship Program continues to maintain contact with the graduates through one-on-one meetings as well as through mentorship and dissemination workshops. Additionally, some of the graduates are serving as host institution mentors while others have been co-opted as facilitators for short courses. At the exit of the Fellowship, graduating Fellows are asked to share their experiences including how enrollment in the program had influenced their career plans in any way. Graduates from the Fellowship Program express a high level of satisfaction with the program and feel that their participation in the 2-year Fellowship enhanced their professional growth as indicated below:

The Fellowship program was a goldmine for me! It gave me the best preparation ground towards fulfilling my career dream of becoming a health communication expert. (Graduate, 2003–2005 intake)

I have improved my leadership skills and deepened my knowledge in designing and managing nutritional interventions in the context of HIV/AIDS. Through the radio talk shows, print media, face-to-face contact, and organizational policy formulation, I have influenced the nutritional attitudes, and practices of health care providers and persons living with and affected by HIV and AIDS. (Graduate, 2008–2010 intake)

Collectively, these experiences suggest that the Fellowship program not only improved Fellows’ professional competencies but also transformed them in diverse ways, increasing their visibility as well as their competitiveness on the job market.

Impact on host institutions and programs

The Fellowship Program has made an appreciable impact on the host institutions as a result of the action learning activities of the Fellows and host institution staff that they have worked closely with. The main areas of impact have been in monitoring and evaluation, strategic planning, systems design, program design, operations research, and capacity building (Table 1).

Table 1.

Impact of the long-term Fellowship program on host institutions and programs

| Impact area | Example |

|---|---|

| Strategic planning | A Fellow attached to the National Uganda AIDS Commission played a leading role in the development of the national monitoring and evaluation framework (2003/2004–2005/2006) for the national response against HIV/AIDS. |

| Electronic media program design | A Fellow attached to Wavah Broadcasting Services (WBS) Television Station developed and produced 10 HIV/AIDS-related documentaries dubbed the ‘Prescription Series’ aimed at enhancing population awareness about the realities of the pandemic. |

| Operations research | A Fellow attached to the Academic Alliance participated in piloting the first provider-initiated testing and counseling (PITC) intervention in Uganda that eventually influenced policy revision and scaling-up of PITC services in Uganda. |

| Capacity building | A Fellow attached to the Jinja District Health Office trained district staff in the use and maintenance of the comprehensive monitoring and reporting system for Jinja HIV/AIDS district activities that he helped to develop. |

| Health management information system | A Fellow attached to Reach Out Mbuya put in place a comprehensive Health Management Information System (HMIS) for integrated HIV and primary health care services at the Kasaala Health Center. |

The monitoring and evaluation area was the most commonly developed program area probably because it was the least developed in most host institutions and thus was always a priority host institution need. Fourteen of the 54 program graduates supported their host institutions in setting up or improving existing monitoring and evaluation systems, while 12 Fellows implemented monitoring and evaluation assignments that improved service delivery.

Program implementation challenges

Despite the successes registered in the past 8 years, the Fellowship Program also faced a number of implementation challenges. For instance, during our ongoing interactions with the Fellows in the course of the Fellowship, Fellows reported that they found it challenging to balance views and expectations from multiple stakeholders (i.e. academic and host mentors as well as the program), especially in the face of divergent views. To address this challenge, the program organizes joint quarterly meetings that are attended by the academic and host mentors as well as the program staffs to ensure harmony in case of divergent views.

The concept of a Fellowship is not widely known or used in the Ugandan context. The presence and the roles of a Fellow within an institution need to be explained clearly to all staff within the institution at the onset in order assist the Fellows to settle in.

The Fellows need to be exposed to challenging assignments to encourage learning and development of problem-solving skills but depending on the needs and staffing capacity, the work can be overwhelming. The program reviews and discusses the terms of reference with the academic and host mentors to ensure a balance and exposure to multiple leadership opportunities.

Academic and host institution mentors are very busy since they have other full-time assignments. The concept of the ‘floating mentors” was introduced to provide additional support to Fellows in crosscutting needs.

We have already noted that the Fellowship program employs rigorous selection criteria to identify the best candidates for the Fellowship, and maintains a strict follow-up mechanism with quarterly supervision and support to the Fellows. Despite these efforts, some of the selected Fellows may not be able to cope with the requirements of the program resulting in an expulsion; three Fellows were terminated due to failure to achieve set program targets. To minimize terminations, there is a need for instituting rigorous selection criteria to identify the right individuals and for Fellows to be adequately supported to respond to performance problems early. The fact that only three Fellows were terminated over the duration of the program could be a reflection of the program's ability to select the right candidates as well as provide them with adequate supervisory support and mentorship to attain program and host institution targets.

Lessons learned

Developing models for enhancing leadership and management capacity in a developing country such as Uganda remains a critical challenge. This program provides an example of a model that has developed middle level cadres into senior managers within a short period of time. Because most of the program graduates are employed in-country and in senior management positions, this program has contributed to increasing the number of well-trained leaders to manage HIV programs in Uganda, which was one of the major gaps and aims for its establishment.

The high retention of the graduates in-country could be attributed to several factors including (1) using local host institutions including rural institutions as placement sites; (2) responding to a critical gap in the HIV sector, which led to rapid absorption of the program graduates into senior leadership positions, thus minimizing the desire to seek employment outside the country; (3) involvement of multiple institutions in the training process and wide dissemination of the achievements and capabilities of the program graduates built confidence and appreciation of the Fellows within the sector. As a result, several program graduates were employed by the institutions where they were hosted; and (4) the hands-on training approach adopted by the program created a cadre of trainees with practical experience in program leadership and management, making it possible for program graduates to compete favorably on the local job market. A recent study of the field epidemiology training programs in Africa has shown similar levels of retention with 80% of Ugandan graduates who completed their training in 1997 still working in Uganda (14). Similar training programs have been designed in other countries including Egypt, Malawi, Ethiopia, Malawi, Iran, Kenya, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe (4–6, 14–18).

For this kind of program to succeed, there should be mutual benefits for Fellows and host institutions. The terms of reference for the Fellows are generated by the institutions based on their needs. The Fellows also document their career plans at the onset, which facilitates the matching of Fellows’ and institutional needs. Our experience shows that nearly half of the Fellows implemented projects that supported institutions in strengthening their monitoring and evaluation systems. This was in response to the institutional capacity gaps in this field and partly a result of Fellows’ interests in furthering their professional career in the field of monitoring and evaluation. Through implementing their programmatic activities at the host institutions, Fellows are able to not only learn how programs are designed, implemented, and evaluated, but they also make significant contributions to the improvement of systems and service delivery at the institutions where they are hosted. This symbiotic relationship has enhanced program acceptability.

The success of the program hinges on a number of inter-related elements including support from mentors, stakeholder involvement, and the hands-on approach employed in delivering the training. The other factors that contributed to its success include open and challenging learning environment provided by the host institution, support from the School of Public Health faculty, the skills building courses, and the pro-activeness of Fellows to maximize learning opportunities. The success of such programs also requires a large pool of mentors who understand and appreciate the role of mentorship in training. Several graduates from this program currently host and mentor Fellows at their institutions, and facilitate the short courses that are conducted at the school. This has expanded the pool of capable mentors to support expansion of this and other related programs in Uganda.

The implementation of this program calls for availability of substantial resources to support the Fellows over the 2-year period, provide logistical support to the Fellows, and host institutions and hire staff to support the program. We are currently in the process of evaluating the long-term Fellowship program. This includes an assessment of the potential effect of the program on Fellows’ career paths and determination of the average cost per Fellow to go through the program. We appreciate the fact that this information would have been useful for this paper; unfortunately, this is not possible yet. However, we believe that while the cost of the program may be substantial, the potential benefits are tremendous in terms of improvement in the efficiency and effectiveness of health programs.

Conclusion

The Fellowship program offers an opportunity for hands-on training in program leadership and management, and demonstrates the importance of stakeholder involvement and mentorship in the training of leaders and managers in real-work situations. This model can be adopted in countries with similar leadership challenges.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support received from the faculty and staff at Makerere University School of Public Health, host, academic, and floating mentors in the implementation of the program. We would also like to acknowledge the financial and technical support received from CDC in the implementation of this program.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors of this article participated in the implementation of the program as described. The program was supported by grants U62/CCUO 20671 and U2G/PS000 971 from the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC).

References

- 1.Anywangwe SCE, Mtonga C. Inequities in the global health workforce: the greatest impediment to health in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2007;4:93–100. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2007040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waddington C, Egger D, Travis P, Hawken L, Dovlo D. Towards better leadership and management in health: Report on an international consultation on strengthening leadership and management in low-income countries. Making Health Systems Work: Working paper No. 10 WHO/HSS/healthsystems/2007.3 Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization. Accessed from: http://www.who.int/management/working_paper_10_en_opt.pdf [cited 8 January 2011]

- 3.Sherk KE, Nauseda F, Johnson S, Liston D. An experience of virtual leadership development for human resource managers. Hum Res Health. 2009;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour M, Mansour JB, El Swesy AH. Scaling up proven public health interventions through a locally owned and sustained leadership development program in rural Upper Egypt. Hum Res Health. 2010;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe LA, Brillant SB, Cleveland E, Dahn BT, Ramanadhan S, Podesta M, Bradley EH. Building capacity in health facility management: guiding principles for skills transfer in Liberia. Hum Res Health. 2010;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DS, Tshimanga M, Worlk G, Nsubuga P, Sunderland NL, hader SL, St Louis ME. Increasing leadership capacity for HIV/AIDS programs by strengthening public health epidemiology and management training in Zimbabwe. Hum Res Health. 2009;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starcevich MM. Coach, mentor: is there a difference? CEO Center for Coaching and Mentoring, Inc. 2009. Available from: http://www.coachingandmentoring.com/Articles/mentoring.html [cited 5 November 2010]

- 8.Healy CC, Welchert AJ. Mentoring relations: a definition to advance research and education. Educ Res. 1990;19:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mugyenyi P, Sewankambo NK, editors. Clinical Operational and Health Services Research (COHRE) Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers; 2008. Mentors’ manual for health sciences training in Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray J, Armstrong P. Academic health leadership: looking to the future. Clin Invest Med. 2003;26:315–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeAngelis CD. Professors not professing. JAMA. 2004;292:1060–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine. A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makerere University School of Public Health Annual Report: August 2009-July 2010. Kampala, Uganda. Available from: http://www.musph.ac.ug/docs/MUSPH%20ANNUAL%20REPORT%202009_2010%204%20web.pdf [Cited 8 January 2011]

- 14.Mukanga D, Namusisi O, Gitta SN, Pariyo G, Tshimanga M, Weaver A, Trostle M. Field epidemiology training programs in Africa - where are the graduates? Hum Res Health. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.I-TECH. Malawi Fellowship Opportunities. Available from: http://www.go2itech.org/employment/open-positions/advert-application_fellowship_mw_merged_sept2010-1.docx/view [cited 12 October 2010]

- 16.Feldman MD, Huang L, Guglielmo BJ, Jordan R, Kahn J, Creasman JM, Wiener-Kronish JP, Lee KA, Tehrani A, Yaffe K, Brown JS. Training the next generation of research mentors: the University of Calfornia, San Francisco, Clinical & Translational Science Institute Mentor Development Program. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2(3):216–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2009.00120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNabb ME, Hiner CA, Pfitzer A, Abduljewad Y, Nadew M, Faltamo P, Anderson J. Tracking working status of HIV/AIDS-trained service providers by means of a training information monitoring system in Ethiopia. Hum Res Health. 2009;7:29. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omar M, Gerein N, Tarin E, Butcher C, Pearson S, Heidari G. Training evaluation: a case study of training Iranian health managers. Hum Res Health. 2009;7:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]