Abstract

Cryptosporidium parvum is a protozoan parasite that infects gastrointestinal epithelial cells and causes diarrheal disease in humans and animals globally. Pathological changes following C. parvum infection include crypt hyperplasia, a modest inflammatory reaction with increased infiltration of lymphocytes into intestinal mucosa. Expression of adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), on infected epithelial cell surfaces may facilitate adhesion and recognition of lymphocytes at infection sites. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNA molecules of 23 nucleotides that negatively regulate protein-coding gene expression via translational suppression or mRNA degradation. We recently reported that microRNA-221 (miR-221) regulates ICAM-1 translation through targeting the ICAM-1 3′-untranslated region (UTR). In this study, we tested the role of miR-221 in regulating ICAM-1 expression in epithelial cells in response to C. parvum infection using an in vitro model of human biliary cryptosporidiosis. Up-regulation of ICAM-1 at both message and protein levels was detected in epithelial cells following C. parvum infection. Inhibition of ICAM-1 transcription with actinomycin D could only partially block C. parvum-induced ICAM-1 expression at the protein level. Cryptosporidium parvum infection decreased miR-221 expression in infected epithelial cells. When cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct covering the miR-221 binding site in the ICAM-1 3′-UTR and then exposed to C. parvum, an enhanced luciferase activity was detected. Transfection of miR-221 precursor abolished C. parvum-stimulated ICAM-1 protein expression. In addition, expression of ICAM-1 on infected epithelial cells facilitated epithelial adherence of co-cultured Jurkat cells. These results indicate that miR-221-mediated translational suppression controls ICAM-1 expression in epithelial cells in response to C. parvum infection.

Keywords: Epithelial cells, MicroRNAs, Cryptosporidium parvum, ICAM-1, Lymphocytes, Adhesion molecules, Inflammation

1. Introduction

The protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium spp. is resistant to the standard disinfection applied to drinking water and has been recognized as one of the leading causes of waterborne disease outbreaks worldwide (Guerrant, 1997). Infection by Cryptosporidium parvum causes an acute, self-limited diarrheal disease in immunocompetent individuals, but causes life-threatening syndromes in immunocompromised patients (Chen et al., 2002). Humans are infected by ingesting C. parvum oocysts which then excyst in the gastrointestinal tract releasing sporozoites to infect intestinal epithelial cells. Cryptosporidium parvum sporozoites can migrate to infect the epithelial cells lining the biliary tract, particularly in patients with HIV/AIDS (Chen et al., 2002). Cryptosporidial infection is usually limited to epithelial cells at the mucosal surface and, thus, C. parvum is classified as a “minimally invasive” mucosal pathogen (Guerrant, 1997; Chen et al., 2002).

Both innate and adaptive immunity are involved in the resolution of cryptosporidiosis and resistance to infection (Chen et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2005). The invasion of intestinal and biliary epithelial cells by C. parvum in vitro activates epithelial cells, resulting in the production and secretion of various cytokines and chemokines and anti-microbial peptides (e.g., β-defensins and cathelicidins) that can kill C. parvum or inhibit parasite growth (Chen et al., 2005; Ehigiator et al. 2005; Barakat et al., 2009). MyD88-deficient mice and IFN-γ- or TNF-α-deficient mice are more sensitive to C. parvum infection (Lacroix et al., 2001; Rogers et al., 2006), and acquired resistance to cryptosporidial infection is dependent upon T-cells (McDonald et al., 2000; Deng et al., 2004). Specific IgG, IgM, IgA and even IgE antibodies occur in acute or convalescent sera from infected patients. However, the mechanisms by which epithelial cells elicit host immune responses against C. parvum infection are not fully understood. Due to the “minimally invasive” nature of C. parvum, understanding how host epithelial cells coordinate the innate and adaptive immunity, orchestrating a finely-controlled anti-C. parvum defense, is crucial to development of therapeutic strategies.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a newly identified class of endogenous small regulatory RNAs that mediate either mRNA cleavage or translational suppression, resulting in gene silencing (Bartel, 2004). More than 700 miRNAs have been identified in humans and are postulated to control 20-30% of human genes (Bartel, 2004; Kim and Kim, 2007). miRNAs can be envisioned as a mechanism to fine-tune cellular responses to the environment, and may be regulators of host anti-microbial immune responses. We have recently characterized alterations in miRNA expression profiles in cultured human biliary epithelial cells following C. parvum infection (Chen et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2009). Importantly, miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation may regulate expression of genes critical to epithelial anti-microbial defense. Specifically, let-7i targets Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and regulates TLR4-mediated anti-C. parvum defense (Chen et al., 2007). miRNA-513 (miR-513), inhibits expression of B7-H1, a member of the B7 family of co-stimulatory molecules, and down-regulation of miR-513 is involved in C. parvum-induced B7-H1 expression in epithelial cells (Gong et al., 2010). Functional manipulation of select miRNAs in epithelial cells alters C. parvum infection burden in vitro (Chen et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2009). Thus, regulation of miRNA genes is an important component of epithelial reactions in response to C. parvum infection.

The intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54) is a 90 kDa member of the Ig superfamily expressed by several cell types including endothelial cells and epithelial cells. ICAM-1 is long known for its importance in stabilizing cell-cell interactions and is critical for the firm arrest and transmigration of leukocytes out of blood vessels into tissues. ICAM-1 is constitutively present on endothelial cells and epithelial cells, but its expression is increased by pro-inflammatory cytokines or following microbe infection (Rui-Mei et al., 1998; Whiteman et al., 2003; Sajjan et al., 2006; Omagari et al., 2009). We previously reported that miRNA-221 (miR-221) suppresses ICAM-1 translation and regulates ICAM-1 expression in human biliary epithelial cells in response to inflammatory stimuli (Hu et al., 2010). In this study, we show that up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in host epithelial cells following C. parvum infection in vitro involves down-regulation of miR-221. Moreover, C. parvum infection enhances adherence of infected epithelial cells by co-cultured Jurkat cells with the involvement of ICAM-1. Thus, a miRNA-mediated regulatory mechanism of ICAM-1 expression has been identified in C. parvum-infected epithelial cells, a process relevant to activation of the host’s defense against C. parvum infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cryptosporidium parvum and epithelial cells

Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts of the Iowa strain were purchased from a commercial source (Bunch Grass Farm, Deary, ID, USA). H69 cells (a gift of Dr. D. Jefferson, Tufts University, USA) are SV40-transformed human biliary epithelial cells originally derived from a normal liver harvested for transplant (Grubman et al., 1994). Human intrahepatic biliary epithelial (HIBEpiC) cells are non-immortalized isolated human biliary epithelial cells commercially available from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, USA) (Hu et al., 2010). Jurkat cells were purchased from ATCC, USA. Actinomycin D was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, USA).

2.2. In vitro infection model

An in vitro model of biliary cryptosporidiosis using cultured biliary epithelial cells was employed as previously described (Verdon et al., 1997). Before infecting cells, oocysts were treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite on ice for 20 min followed by extensive washing with DMEM-F12 medium. Oocysts were then added to the cell culture to release sporozoites to infect cells (Seydel et al., 1998). Infection was done in a culture medium (DMEM-F12 with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) containing viable C. parvum oocysts (oocysts with host cells in a 10:1 ratio). Infection was quantitated with indirect immunofluorescent microscopy or real-time PCR as previously reported (Chen et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2010).

2.3. Western blots

Whole cell lysates were obtained from cells with M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce). A total of 40 μg lysate proteins was loaded in 4-12% SDS-PAGE transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, USA). Antibodies to ICAM-1 (Cell Signaling, USA) and actin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Densitometric levels of ICAM-1 signals were quantified and expressed as their ratio to actin.

2.4. Anti-miRNA and precursor to miR-221

To manipulate cellular function of miR-221, we utilized an antisense approach to inhibit miR-221 function and transfection of cells with miR-221 precursor to increase miR-221 expression. For experiments, cells were grown to 70% confluence and treated with anti-miR-221 (antisense 2-methoxy oligonucleotide to miR-221, Ambion) or the miR-221 precursor (Ambion) using the lipofectamine™ 2000 reagent (Invitrogen).

2.5. Real-time PCR

For quantitative analysis of mRNA expression, comparative real-time PCR was performed with the use of the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The sequences for the amplification of human ICAM-1 were: 5- CGCAAGGTGACCGTGAATGT -3 (forward) and 5- CGTGGCTTGTGTGTTCGGTT -3 (reverse). The primer sequences for the amplification of the gene for Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were as follows: 5- TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC -3 (forward); 5- GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG -3 (reverse).

For analysis of miR-221, total RNA was isolated from cells using the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation kit (Ambion). Comparative real-time PCR was performed using the Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Specific primers and probes for mature miR-221 and for the non-coding small nuclear RNA (snRNA) RNU6B were obtained from Applied Biosystems. All reactions were run in triplicate. The amount of miR-221 was obtained by normalizing to snRNA RNU6B, and relative to controls (untreated cells) as previously reported (Hu et al., 2010).

2.6. Northern blots

Total RNAs harvested as above were run on a 15% Tris/Borate/EDTA [90 mM Tris/64.6 mM boric acid/2.5 mM EDTA (pH 8.3)] urea gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a Nytran nylon transfer membrane (Ambion). An LNA DIG-probe for miRNA-221 (Exiqon, USA) was hybridized using UltraHyb reagents (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with blotted snRNA RNU6B as a control.

2.7. Luciferase reporter constructs and luciferase assay

Complementary 40 bp DNA oligonucleotides containing the putative miR-221 target site within the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of human ICAM-1 were synthesized and cloned into the multiple cloning sites of the pMIR-REPORT Luciferase vector (Ambion) as previously reported (Hu et al., 2010). In this vector, the post-transcriptional regulation of luciferase was potentially regulated by miRNA interactions with the ICAM-1 3′UTR. Another pMIR-REPORT Luciferase construct containing mutant 3′UTR (TGTAGC to ACATCG) was applied as a control. Cells were transfected with each reporter construct, as well as anti-miR-221 or miR-221 precursor, followed by assessment of luciferase activity 24 h after transfection. Luciferase activity was measured and normalized to control β-galactosidase (β-gal) (Chen et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2010).

2.8. Cell adhesion assay

A fluorescent labeling approach was used to assess epithelial cell-mediated adhesion of T-cells as previously reported (Frick et al., 2000). Briefly, Jurkat cells were first activated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA 20 nM) for 48 h and then labeled with the fluorogenic dye calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein AM, 1 μg/ml, Molecular Probes). Labeled Jurkat cells (2 × 105) were then added and incubated with pre-infected epithelial cells (1 × 105) in 24-well plates at 37°C for 15 min. Non-adhered cells were washed away by gently shaking each twice for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence-positive cells in the plates, reflecting adhered and labeled Jurkat cells, were counted under the fluorescence microscope and presented as a percentage of controls (Frick et al., 2000). Representative images were taken under a Carl Zeiss fluorescent microscope. Blocking experiments were conducted by incubating C. parvum-infected epithelial cells with a neutralizing antibody to ICAM-1 (10 μg/ml, R&D systems) for 60 min at 37°C. Treated cells were extensively washed with culture medium to remove free antibodies before the addition of the Jurkat cells. Non-specific IgG isotype (R&D systems) was used as a control.

3. Results

3.1. Host epithelial cells up-regulate ICAM-1 expression following C. parvum infection

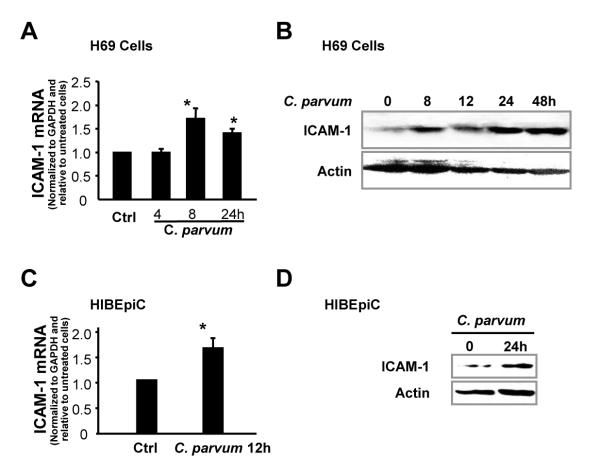

First, CAM-1 expression was tested in host epithelial cells following C. parvum infection using Western blot and real-time PCR. Two human biliary epithelial cell lines (H69 and HIBEpiC) were applied to the study. A significant increase of ICAM-1 at the mRNA level was detected in H69 cells after exposure to C. parvum for 8 h and 24 h (Fig. 1A). A time-dependent increase of ICAM-1 at the protein level was found in H69 cells after exposure to C. parvum for up to 48 h (Fig. 1B). Increase of ICAM-1 mRNA, as well as ICAM-1 protein, was further confirmed in HIBEpiC following C. parvum infection (Fig. 1C,D).

Fig. 1.

Human biliary epithelial cells (H69 and HIBEpiC) up-regulate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression following Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro. (A and B) Expression of ICAM-1 at the message and protein levels in H69 cells following C. parvum infection. H69 cells were exposed to C. parvum followed by real-time PCR (after incubation for up to 24 h) or Western blot analysis for ICAM-1 (after incubation for up to 48 h). (C and D) ICAM-1 expression in HIBEpiC induced by C. parvum. Cells were exposed to C. parvum followed by real-time PCR (C) or Western blot (D). Bars represent the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus non-infected cells. GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

3.2. Post-transcriptional regulation is involved in the upregulation of ICAM-1 in epithelial cells following C. parvum infection

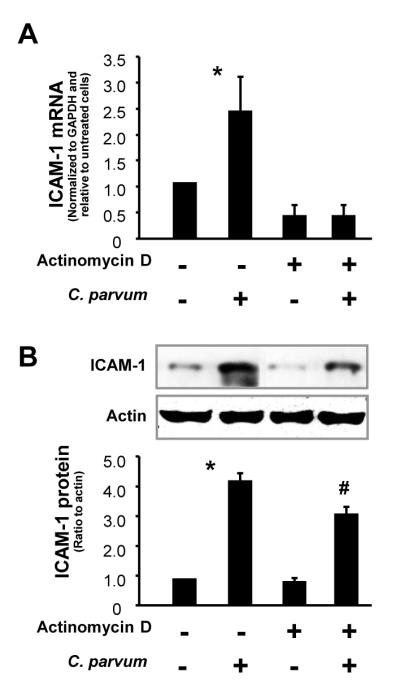

To clarify whether post-transcriptional regulation is involved in the up-regulation of ICAM-1 expression following C. parvum infection, we tested the expression of ICAM-1 proteins in H69 cells after C. parvum infection in the presence of a transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D (Whiteman et al., 2003). H69 cells were treated with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) for 90 min and exposed to C. parvum in the presence of actinomycin D for additional 12 h (for ICAM-1 mRNA measurement) or 24 h (for ICAM-1 protein detection). Treatment with actinomycin D did not affect the attachment and cellular invasion of C. parvum to H69 cells (data not shown). We found a complete inhibition of up-regulation of ICAM-1 at the message level in C. parvum-infected cells treated with actinomycin D (Fig. 2A). Inconsistent with the message expression, a significant up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein was detected in C. parvum-stimulated cells after treatment with actinomycin D (Fig. 2B), suggesting that post-transcriptional mechanisms are involved in the up-regulation of ICAM-1 in epithelial cells following C. parvum infection.

Fig. 2.

Post-transcriptional regulation is involved in the up-regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) protein in cells following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Expression of ICAM-1 at the message (A) and protein (B) levels in H69 human biliary epithelial cells following C. parvum infection in the presence or absence of actinomycin D. H69 cells were exposed to culture medium with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) for 90 min and then exposed to C. parvum for 24 h followed by real-time PCR (A) and Western blot (B) for ICAM-1. Data are representative of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 one-way by ANOVA test versus non-infected cells; #, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus actinomycin D-treated cells. GAPDH , Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

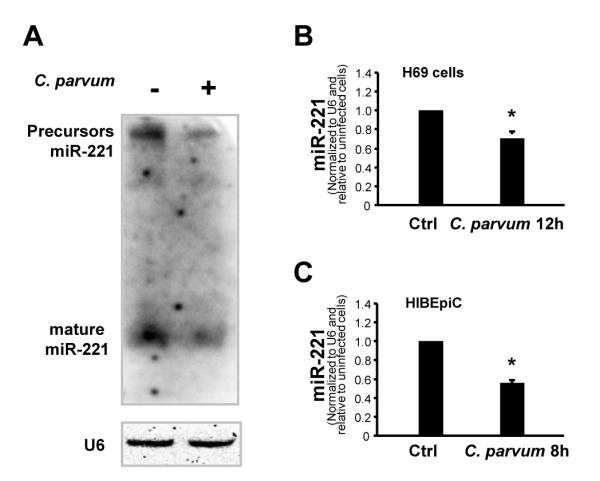

3.3. Down-regulation of miR-221 expression occurs in epithelial cells following C. parvum infection

miRNAs regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level (Bartel, 2004). We previously demonstrated that miR-221 targets ICAM-1 3′UTR, resulting in translational repression in biliary epithelial cells (Hu et al., 2010). To test whether miR-221-mediated ICAM-1 translational repression is involved in the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in cells following C. parvum infection, we measured expression of miR-221 in H69 and HIBEpiC cells after exposure to C. parvum for up to 24 h. Decreased expression of miR-221, both at the levels of its primary transcript and mature forms, was detected by Northern blot analysis in H69 cells after exposure to C. parvum infection for 24 h (Fig. 3A) using a probe that recognizes miR-221 primary transcript and mature miR-221 (Hu et al., 2010). Decreased expression of mature miR-221 in cells following C. parvum infection was confirmed by real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 3B,C).

Fig. 3.

Down-regulation of microRNA-221 (miR-221) - expression occurs in epithelial cells following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. (A) Cryptosporidium parvum infection decreased miR-221 expression in H69 human biliary epithelial cells, as assessed by Northern blot. Cells were exposed to C. parvum for 12 h followed by Northern blot for miR-221. Small nuclear RNA RNU6B (U6) was blotted to ensure equal loading. (B and C) Decreased expression of mature miR-221 in H69 and HIBEpiC cells following C. parvum infection, as assessed by real-time PCR. H69 and HIBEpiC cells were exposed to C. parvum for 12 h followed by real-time PCR for miR-221. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus non-infected cells in B and C.

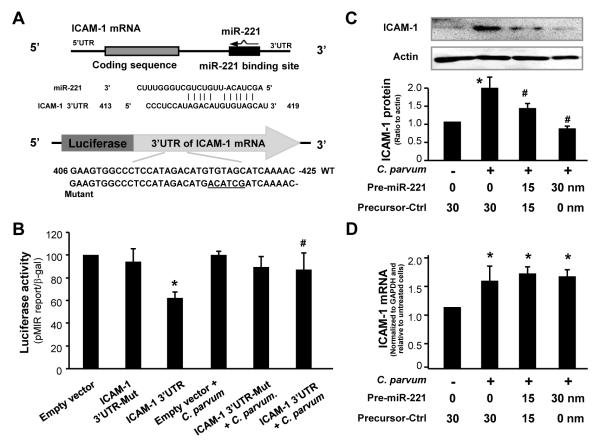

3.4. Down-regulation of miR-221 is involved in the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in epithelial cells following C. parvum infection

Because miR-221 targets ICAM-1 3′UTR and induces translational suppression (Hu et al., 2010), we expected that down-regulation of miR-221 in C. parvum-infected cells should cause a relief of miR-221-suppressed ICAM-1 translation. To test this possibility, we used a pMIR-REPORT luciferase construct containing the ICAM-1 3′-UTR with the putative miR-221 binding site or a construct with the TGTAGC to ACATCG mutation at the putative binding site (Hu et al., 2010) to transfect H69 cells (Fig. 4A). Transfected cells were then exposed to C. parvum for 24 h, followed by assessment of luciferase activity. Consistent with our previous results (Hu et al., 2010), a significant decrease of luciferase activity was detected in cells transfected with the ICAM-1 3′-UTR construct containing the potential binding site compared with the empty vector control (Fig. 4B), suggesting endogenous translational repression of the construct with the ICAM-1 3′-UTR. No change of luciferase was observed in cells transfected with the mutant ICAM-1 3′-UTR construct (Fig. 4B). Cells exposed to C. parvum for 24 h reversed the decrease of the ICAM-1 3′UTR-associated luciferase activity compared with the non-infected cells. No significant change of luciferase activity was found in C. parvum-infected cells transfected with the mutant and empty vector control (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Down-regulation of microRNA-221 (miR-221) is involved in the up-regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) protein in cells following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. (A) The luciferase reporter constructs containing the potential binding site for miR-221 in ICAM-1 3′ untranslated region (UTR) or the mutant sequence (TGTAGC to ACATCG, underlined) were generated. (B) H69 human biliary epithelial cells were transiently co-transfected with the reporter constructs and then exposed to C. parvum for 24 h. Luciferase activities were measured and normalized to the control β-galactosidase level. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus 3′UTR mutant; #, P < 0.05 P one-way ANOVA test versus ICAM-1 3′UTR reporter construct. (C) miR-221 precursor blocked up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in cells in response to C. parvum infection. H69 cells were transfected with the miR-221 precursor or a control non-specific precursor for 48 h and then exposed to C. parvum for 24 h, followed by Western blot for ICAM-1. (D) miR-221 precursor does not alter C. parvum-stimulated ICAM-1 expression at the message level. H69 cells were transfected with the miR-221 precursor for 24 h and then exposed to C. parvum for 8 h, followed by real-time PCR analysis for ICAM-1 mRNA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Precursor-Ctrl = non-specific precursor control. *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus non-infected cells; #, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus non-miR-221 precursor-treated infected cells (in D).

To further test whether miR-221-mediated ICAM-1 translational repression is indeed involved in the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in cells following C. parvum infection, we transfected H69 cells with various doses of miR-221 precursors for 48 h and then exposed cells to C. parvum for 24 h, followed by Western blot analyses for ICAM-1 protein. The precursor to miR-221 significantly inhibited the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in H69 cells following C. parvum infection (Fig. 4C) in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, transfection of miR-221 precursor can abolish the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in epithelial cells in response to C. parvum infection. Moreover, no significant change in ICAM-1 mRNA levels was found in miR-221 precursor-treated cells at 24 h following C. parvum infection, compared with cells treated with the control precursor or the non-treated control cells (Fig. 4D). Taken together, the above data suggest that down-regulation of miR-221 is required for the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in host epithelial cells following C. parvum infection.

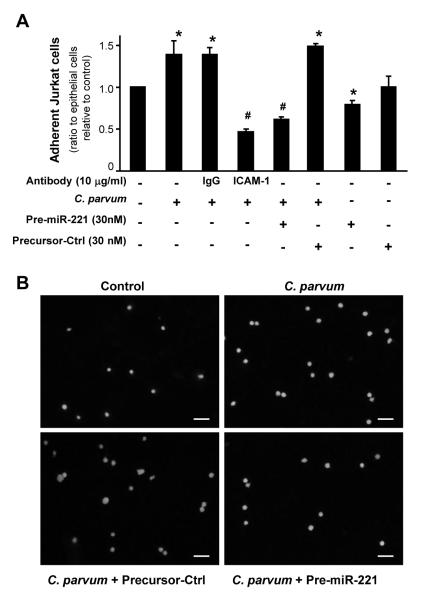

3.5. Up-regulation of ICAM-1 in response to C. parvum infection affects Jurkat cell adherence

Localized infiltration of neutrophils and lymphocytes has been reported in the intestinal and biliary tract following C. parvum infection (Tilley et al., 1995; McDonald et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2005). To determine the functional relevance of C. parvum-associated expression of ICAM-1 to lymphocyte infiltration, we performed an adhesion assay to assess the adherence of infected H69 cells by co-cultured Jurkat cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, H69 cells with an enhanced ICAM-1 expression due to C. parvum infection showed a significantly increased adherence to Jurkat cells, compared with control non-C. parvum infected cells. A neutralizing antibody to ICAM-1 blocked associated adherence by co-cultured Jurkat cells. Importantly, the over-expression of miR-221 in H69 cells through transfection of miR-221 precursor also blocked the adherence of Jurkat cells to C. parvum-infected cells (Fig. 5A). A non-specific precursor control showed no effect on the adherence of Jurkat cells to C. parvum-infected cells. In addition, H69 cells transfected with the miR-221 precursor alone showed a modest decrease in Jurkat cell adherence. No changes in Jurkat cell adherence were detected in H69 cells transfected with the precursor control (Fig. 5A). The infection rate following exposure to C. parvum for 2 h was similar in all cultures, including those treated with the ICAM-1 neutralizing antibody or miR-221 precursor (data not shown), suggesting that those miRNAs do not affect initial parasite host cell attachment and cellular invasion. Effects of miR-221-mediated ICAM-1 expression in biliary epithelial cells induced by C. parvum on adherence of co-cultured Jurkat cells were further confirmed by immunofluorescent microscopy (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Up-regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) protein in H69 human biliary epithelial cells induced by Cryptosporidium parvum affects adherence of co-cultured Jurkat cells. (A) Functional manipulation of microRNA-221 (miR-221) influenced adherence of H69 by co-cultured Jurkat cells in an ICAM-1-dependent manner. H69 cells were exposed to C. parvum for 24 h, followed by treatment with the anti-ICAM-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) or IgG isotype for 1 h. For over-expression of miR-221, H69 cells were first treated with miR-221 precursor or non-specific precursor control (precursor-Ctrl) for 72 h and then exposed to C. parvum. After washing, cells were incubated with the medium containing the IgG isotype control (ctrl) or anti-ICAM-1 mAb for 1 h. Activated Jurkat cells were labeled with the Calcein AM and then incubated with H69 cells. Adherence of Jurkat cells was measured under the fluorescence microscope and presented as the ratio of Jurkat cells:epithelial cells relative to control. *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus the non-treated control; #, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test versus C. parvum-infected group. (B) Effects of up-regulation of ICAM-1 in H69 cells in response to C. parvum on adherence of co-cultured Jurkat cells, as assessed by immunofluorescent microscopy. Calcein AM-labeled Jurkat cells following adherence to H69 cells were shown. Bars = 50 μm.

4. Discussion

Expression of ICAM-1 represents an important element of host epithelial cell reactions in response to microbial infection (Rui-Mei et al., 1998; Sajjan et al., 2006; Omagari et al., 2009). Until recently, most gene expression studies have measured steady-state mRNA levels and, thus, fail to account for different states of translational activation and different stabilities of individual mRNA species (Bartel, 2004; Stoecklin and Anderson, 2006). It is now apparent that the 3′UTR of mRNA can specifically control the rates of translation and degradation of individual mRNA, including targeting by miRNAs (Conne et al., 2000; Bartel, 2004). We recently reported that miR-221 regulates ICAM-1 expression through targeting of ICAM-1 3′UTR. This miR-221-mediated translational suppression is involved in the regulation of ICAM-1 in human epithelial cells in response to the inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ (Hu et al., 2010). Here, we found that epithelial cells activated ICAM-1 transcription and increased ICAM-1 protein expression following C. parvum infection. Inhibition of ICAM-1 transcription could only partially block associated ICAM-1 expression at the protein level. Importantly, we detected a significant decrease in miR-221 expression in cells after C. parvum infection, resulting in relief of translational suppression associated with ICAM-1 3′-UTR containing the miR-221 binding site. Moreover, treatment of cells with miR-221 precursor abolished the up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein in C. parvum-infected cells. Since a control precursor showed no inhibitory effect on associated ICAM-1 protein expression, we speculate that up-regulation of ICAM-1 protein following C. parvum infection involves relief of translational repression through down-regulation of miR-221. Although it is still unclear whether infection may directly impact on ICAM-1 protein stability, our above data indicate that host epithelial cells up-regulate ICAM-1 protein expression following C. parvum infection through both increased transcription of ICAM-1 and relief of miR-221-mediated translational repression.

miR-221 is one of the most abundant miRNAs in epithelial cells, representing approximately 10% of all miRNA clones, second only to miR-21 in biliary epithelial cells (Kawahigashi et al., 2009). The abundance of miR-221 may assure the low basal expression of ICAM-1 protein under physiologic conditions. Therefore, it is plausible that relief of miR-221-mediated translational suppression may be necessary for the stimulated expression of ICAM-1 in epithelial cells and critical to the stimulated expression of ICAM-1 in cells following C. parvum infection. Indeed, transfection of epithelial cells with miR-221 precursor could attenuate C. parvum-stimulated ICAM-1 expression at its protein level; although a high level of ICAM-1 mRNA still persisted after miR-221 precursor treatment.

The mechanisms underlying down-regulation of miR-221 in cells following C. parvum infection are still unclear. Most miRNA genes are transcribed by polymerase II (pol II) and can be classified as class II genes (Lee et al., 2004). Expression of miRNAs can be elaborately controlled through various regulatory mechanisms, including transactivation and transrepression by nuclear transcription factors (Zhou et al., 2009; O’Hara et al., 2010), as well as activation of the miRNA-generating complex at the post-transcriptional level (Paroo et al., 2009; Trabucchi et al., 2009). We have recently identified a panel of miRNAs that are transactivated through activation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in human biliary epithelial cells following C. parvum infection (Zhou et al., 2009). Transcription of the let-7i gene is suppressed by infection via promoter binding by NF-κB subunit p50 along with C/EBPβ (O’Hara et al., 2010). In the current study, we detected a decrease in the miR-221 primary transcript, as well as its precursor and mature forms, in epithelial cells after exposure to C. parvum. Whether TLR4/NF-κB signals are involved in the down-regulation of miR-221 in cells following C. parvum infection is currently under investigation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, are potent activators of ICAM-1 protein expression in T-cells, B-cells, and endothelial and epithelial cells. IFN-γ down-regulates miR-221 expression in a STAT-1-dependent mechanism (Hu et al., 2010). Nevertheless, we failed to detect an increase of IFN-γ in the cell cultures after exposure to the C. parvum parasite (Gong et al., 2010).

The expression of adhesion molecules on the surface of epithelial cells modulates their interactions with other cell types. Adhesion molecules expressed on the epithelial cell surface during microbe infection permit adhesion and recognition of immune cells such as lymphocytes and, subsequently, activation of adaptive immunity. Up-regulation of ICAM-1 in host epithelial cells was evident after infection by various pathogens, including parasites (Rui-Mei et al., 1998; Whiteman et al., 2003; Sajjan et al., 2006; Omagari et al., 2009). Infiltration of inflammatory lymphoid cells has been demonstrated in both intestinal and biliary tissues following C. parvum infection (Tilley et al., 1995; McDonald et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2005). In this study, we confirmed that ICAM-1 expressed on the surface of epithelial cells following C. parvum infection increased the attachment of co-cultured Jurkat cells to infected epithelial cells. A neutralizing antibody to ICAM-1 significantly blocked the attachment of co-cultured Jurkat cells. Functional manipulation of miR-221 in epithelial cells could also influence associated attachment of co-cultured Jurkat cells. Thus, ICAM-1 may have important regulatory functions to ensure a controlled and balanced inflammatory reaction at infection sites during C. parvum infection. Future studies should identify other miR-221 target genes and investigate whether miR-221-mediated expression of ICAM-1 on epithelial cells following C. parvum infection will influence inflammatory infiltration in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, USA Grant AI071321 and by the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Program, USA (LB692) (to X-M.C), and in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30928019 and No. 81041078) (to Y. F). We are grateful to Ms Barbara L. Bittner for her assistance in writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barakat FM, McDonald V, Foster GR, Tovey MG, Korbel DS. Cryptosporidium parvum infection rapidly induces a protective innate immune response involving type I interferon. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200:1548–1555. doi: 10.1086/644601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, Keithly JS, Paya CV, LaRusso NF. Cryptosporidiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:1723–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra013170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, O’Hara SP, Nelson JB, Splinter PL, Small AJ, Tietz PS, Limper AH, LaRusso NF. Multiple Toll-like Receptors are expressed in human cholangiocytes and mediate host epithelial responses to Cryptosporidium parvum via activation of NF-kappaB. J. Immunol. 2005;175:7447–7456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, Splinter PL, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF. A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28929–28938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conne B, Stutz A, Vassalli JD. The 3′ untranslated region of messenger RNA: A molecular ‘hotspot’ for pathology? Nat. Med. 2000;6:637–641. doi: 10.1038/76211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Rutherford MS, Abrahamsen MS. Host intestinal epithelial response to Cryptosporidium parvum. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:869–84. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehigiator HN, Romagnoli P, Borgelt K, Fernandez M, McNair N, Secor WE, Mead JR. Mucosal cytokine and antigen-specific responses to Cryptosporidium parvum in IL-12p40 KO mice. Parasite. Immunol. 2005;27:17–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick AG, Joseph TD, Pang L, Rabe AM, St. Geme JW, Look DC. Haemophilus influenzae stimulates ICAM-1 expression on respiratory epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4185–4196. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong AY, Zhou R, Hu G, Liu J, Sosnowska D, Drescher KM, Dong H, Chen XM. Cryptosporidium parvum induces B7-H1 expression in cholangiocytes by downregulating microRNA-513. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:160–169. doi: 10.1086/648589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubman SA, Perrone RD, Lee DW, Murray SL, Rogers LC, Wolkoff LI, Mulberg AE, Cherington V, Jefferson DM. Regulation of intracellular pH by immortalized human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell lines. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:G1060–1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.6.G1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant RL. Cryptosporidiosis: an emerging, highly infectious threat. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1997;3:51–57. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Gong AY, Liu J, Zhou R, Deng C, Chen XM. miR-221 suppresses ICAM-1 translation and regulates interferon-gamma-induced ICAM-1 expression in human cholangiocytes. Am. J. Physiol. – Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G542–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00490.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahigashi Y, Mishima T, Mizuguchi Y, Arima Y, Yokomuro S, Kanda T, Ishibashi O, Yoshida H, Tajiri T, Takizawa T. MicroRNA profiling of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell lines reveals biliary epithelial cell-specific microRNAs. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 2009;76:188–197. doi: 10.1272/jnms.76.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Kim VN. Processing of intronic microRNAs. EMBO J. 2007;26:775–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix S, Mancassola R, Naciri M, Laurent F. Cryptosporidium parvum-specific mucosal immune response in C57BL/6 neonatal and gamma interferon-deficient mice: role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in protection. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1635–1642. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1635-1642.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald V, Smith R, Robinson H, Bancroft G. Host immune responses against Cryptosporidium. Contrib. Microbiol. 2000;6:75–91. doi: 10.1159/000060371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omagari D, Mikami Y, Suguro H, Sunagawa K, Asano M, Sanuki E, Moro I, Komiyama K. Poly I:C-induced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in intestinal epithelial cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009;156:294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara SP, Splinter PS, Gajdos GB, Trussoni CK, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Chen XM, LaRusso NF. NF-kB p50-CCAAT-enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBPb)-mediated transcriptional repression of microRNA let-7i following microbial infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:216–225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroo Z, Ye X, Chen S, Liu Q. Phosphorylation of the human microRNA-generating complex mediates MAPK/Erk signaling. Cell. 2009;139:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KA, Rogers AB, Leav BA, Sanchez A, Vannier E, Uematsu S, Akira S, Golenbock D, Ward HD. MyD88-dependent pathways mediate resistance to Cryptosporidium parvum infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:549–556. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.549-556.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui-Mei L, Kara AU, Sinniah R. In situ analysis of adhesion molecule expression in kidneys infected with murine malaria. J. Pathol. 1998;185:219–225. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199806)185:2<219::AID-PATH77>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjan US, Jia Y, Newcomb DC, Bentley JK, Lukacs NW, LiPuma JJ, Hershenson MB. H. influenzae potentiates airway epithelial cell responses to rhinovirus by increasing ICAM-1 and TLR3 expression. FASEB J. 2006;20:2121–2123. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5806fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydel KB, Zhang T, Champion GA, Fichtenbaum C, Swanson PE, Tzipori S, Griffiths JK, Stanley SL., Jr. Cryptosporidium parvum infection of human intestinal xenografts in SCID mice induces production of human tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-8. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:2379–1382. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2379-2382.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Anderson P. Posttranscriptional mechanisms regulating the inflammatory response. Adv. Immunol. 2006;89:1–37. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)89001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RC, Olson ME, Zhu G, Enomoto S, Abrahamsen MS, Hijjawi NS. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Adv. Parasitol. 2005;59:77–158. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)59002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley M, McDonald V, Bancroft GJ. Resolution of cryptosporidial infection in mice correlates with parasite-specific lymphocyte proliferation associated with both Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:459–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabucchi M, Briata P, Garcia-Mayoral M, Haase AD, Filipowicz W, Ramos A, Gherzi R, Rosenfeld MG. The RNA-binding protein KSRP promotes the biogenesis of a subset of microRNAs. Nature. 2009;459:1010–1014. doi: 10.1038/nature08025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdon R, Keusch GT, Tzipori S, Grubman SA, Jefferson DM, Ward HD. An in vitro model of infection of human biliary epithelial cells by Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Infect. Dis. 1997;175:1268–1272. doi: 10.1086/593695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SC, Bianco A, Knight RA, Spiteri MA. Human rhinovirus selectively modulates membranous and soluble forms of its intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) receptor to promote epithelial cell infectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11954–11961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Hu G, Liu J, Gong AY, Drescher KM, Chen XM. NF-kappaB p65-dependent transactivation of miRNA genes following Cryptosporidium parvum infection stimulates epithelial cell immune responses. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000681. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]