Abstract

Background

Cavernous nerve (CN) injury during radical prostatectomy (RP) causes CN degeneration and secondary penile fibrosis and smooth muscle cell (SMC) apoptosis. Pentoxifylline (PTX) is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that further inhibits multiple cytokine pathways involved in nerve degeneration, apoptosis, and fibrosis.

Objectives

To evaluate whether PTX enhances erectile function in a rat model of CN injury.

Design, Setting and Interventions

Forty male Sprague-Dawley rats underwent CN crush injury and were randomized to oral gavage feeding of phosphate-buffered saline (vehicle) or PTX 25, PTX 50, or PTX 100 mg/kg per day. Ten animals underwent sham surgery and received vehicle treatment. Treatment continued for 28 d, followed by a wash-out period of 72 h. An additional eight rats underwent resection of the major pelvic ganglion (MPG) for tissue culture and examination of direct effects of PTX on neurite sprouting.

Measurements

Intracavernous pressure recording on CN electrostimulation, immunohistologic examination of the penis and the CN distal to the injury site, and length of neurite sprouts in MPG culture.

Results

Daily oral gavage feeding of PTX resulted in significant improvement of erectile function compared to vehicle treatment in all treated groups. After treatment with PTX 50 and PTX 100 mg/kg per day, the expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the dorsal penile nerve was significantly higher than in vehicle-treated rats. Furthermore, PTX treatment prevented collagen deposition and SMC loss in the corpus cavernosum. In the CN, signs of Wallerian degeneration were ameliorated by PTX treatment. MPG culture in medium containing PTX resulted in a significant increase of neurite length.

Conclusions

PTX treatment following CN injury in rats improved erectile recovery, enhanced nerve regeneration, and preserved the corpus cavernosum microarchitecture. The clinical availability of this compound merits application in penile rehabilitation studies following RP in the near future.

Keywords: Cavernous nerve injury, Cyclic adenosine monophosphate, Cytokines, Erectile dysfunction, Fibrosis, nerve regeneration, Pentoxifylline, Phosphodiesterase inhibitor, TGF beta, TGF alpha

1. Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) remains the most frequent long-term complication of radical prostatectomy (RP), despite recent advances in anatomic knowledge and technology [1]. In an effort to preserve potency in these patients, research efforts have demonstrated the efficacy of neuroimmunophilin ligands, neurotrophins, and stem cells in improving neuroregeneration following cavernous nerve (CN) injury [2–4]. Other approaches to enhance erectile recovery are geared toward preventing secondary collagen deposition and smooth muscle cell (SMC) loss in the corpus cavernosum by targeting antifibrotic and antiapoptotic pathways, respectively [5–7]. Although the results of these studies have been promising, the large majority of tested compounds remain experimental and are not clinically available. In fact, it may take several years before clinical trials are initiated, let alone completed.

Pentoxifylline (PTX) is a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that is further known for its broad-spectrum cytokine inhibitory properties [8,9]. It has been clinically used in a wide variety of conditions. PTX interferes with multiple cytokine pathways, such as those involved in tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling [8–13]. These pathways are involved in both the primary nerve degeneration following CN injury, and the secondary development of penile fibrosis and SMC apoptosis [11,14–17]. PTX might therefore be an interesting candidate for penile rehabilitation following RP. This study aimed to investigate the effects of chronic administration of PTX on erectile function, nerve regeneration, SMC preservation, and corporeal fibrosis in a rat model of CN crush injury.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Fifty male Sprague-Dawley rats (12 wk old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Rats had access to standard rat chow and water ad libitum. Forty animals underwent bilateral CN crush injury and were randomized to once-daily oral gavage feeding of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; vehicle), PTX 25, PTX 50, or PTX 100 mg/kg per day starting at the day of surgery. The remaining 10 animals underwent sham surgery and vehicle treatment. Dosages were based on human–rat dose translation on a body-surface-area basis with the highest dose (100 mg/kg per day) based on the currently used dosage in humans. Treatment was continued for 28 d, followed by a wash-out period of 72 h before erectile function measurement. Following functional testing, the animals were sacrificed and the penis and CNs were harvested for histology. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Francisco.

2.2. Cavernous nerve crush injury

Under inhalant anesthesia, the major pelvic ganglion (MPG) and CN were exposed on either side of the prostate via laparotomy. In sham animals, the abdomen was then closed. In the treatment and vehicle groups, standardized bilateral CN crush injury was performed as described previously [4].

2.3. Assessment of erectile function

Four weeks after CN crush or sham surgery, erectile function was assessed. Under ketamine (100 mg/kg) and midazolam (5 mg/kg) anesthesia, the MPG and CN were exposed bilaterally via midline laparotomy. A 25-G butterfly needle was inserted into the proximal left corpus cavernosum, filled with 250 U/ml heparin solution, and connected to a pressure transducer (Utah Medical Products, Midvale, UT, USA) for intracavernous pressure (ICP) measurement. The ICP was recorded at a rate of 10 samples per second. A bipolar stainless-steel hook electrode was used to stimulate the CN directly (each pole 0.2 mm in diameter, separated by 1 mm) via a signal generator (National Instruments, Austin, Texas, USA) and custom-built constant-current amplifier generating monophasic rectangular pulses with stimulus parameters of 5 mA, 20 Hz, pulse width of 0.2 ms, and duration of 50 s. Three stimulations were conducted on either side separately, and the maximal amplitude of ICP during nerve electrostimulation was calculated from baseline value and included for statistical analysis in each animal. Systemic blood pressure was recorded using a 23-G butterfly needle inserted into the aorta at the level of the iliac bifurcation for the calculation of the ratio of ICP increase to mean arterial pressure (MAP). After functional testing, animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (200 mg/kg) followed by bilateral thoracotomy. The penis and the distal CN were then harvested for histologic analysis.

2.4. Histology

2.4.1. Immunofluorescence

Freshly dissected tissue was fixed for 4 h with cold 2% formaldehyde and 0.002% picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, followed by overnight immersion in buffer solution containing 30% sucrose. Tissues were frozen in optimum cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and stored at −80°C until use. Sections were cut at 5 µm, adhered to charged slides, air dried for 10 min, and rehydrated with PBS. Goat serum 3% in PBS was applied as blocking agent for 30 min. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, followed by 1 h incubation in 1:500 dilution of secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or Alexa fluor 594 (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies were rabbit antineuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) 1:400 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and mouse antineurofilament 1:400. (The mouse antineurofilament antibody, developed by J. Wood, was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA, USA). Actin was stained by incubation over 20 min with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin 1:500 (Invitrogen) in 4% paraformaldehyde. Nuclear staining was performed by 2-min incubation in 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; D-3571, Invitrogen).

2.4.2. Histochemistry

For collagen histochemistry, slides were rehydrated in PBS, immersed in picrosirius red stain (American master tech scientific, Lodi, CA, USA) for 1 h, and rinsed with 0.5% acetic acid water twice.

2.4.3. Digital analysis of sections

Three midpenile tissue sections per animal were included for statistical analysis. Slides were photographed and recorded using a Retiga 1300 digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada) attached to a Nikon E300 microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA). Computerized histomorphometric analysis was performed using Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). As harvest of the part of the CN distal to the crush injury site is complicated by fibrosis and scarring, we were not technically able to correctly identify and/or resect the portion distal to the crush site in all rats. Therefore, sections of the distal portion of the CN were not subject to statistical analysis and serve the purpose of microanatomic illustration of nerve degeneration and regeneration only.

2.5. Major pelvic ganglion culture

A separate group of eight 12-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats underwent harvesting of both MPGs for the purpose of tissue culture as was previously described in detail [3]. All MPG fragments were incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (UCSF cell culture facility) containing PTX at 0 nM (control), 100 nM, 10 µM, and 100 µM. MPG fragments were then cultured in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 for 48 h. At 48 h, MPG fragments were examined under the inverted microscope for neurite outgrowth at magnification ×100. The 10 longest neurites from each segment were measured; mean neurite length per fragment was calculated and used for statistical analysis.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed using Medcalc v.11.0.0.0 (Medcalc software, Belgium). To test the difference between the means of multiple treatment groups, analysis of variance and post hoc analysis according to Tukey-Kramer were used. Results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. Data are shown as mean plus or minus standard error of the mean.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of erectile function

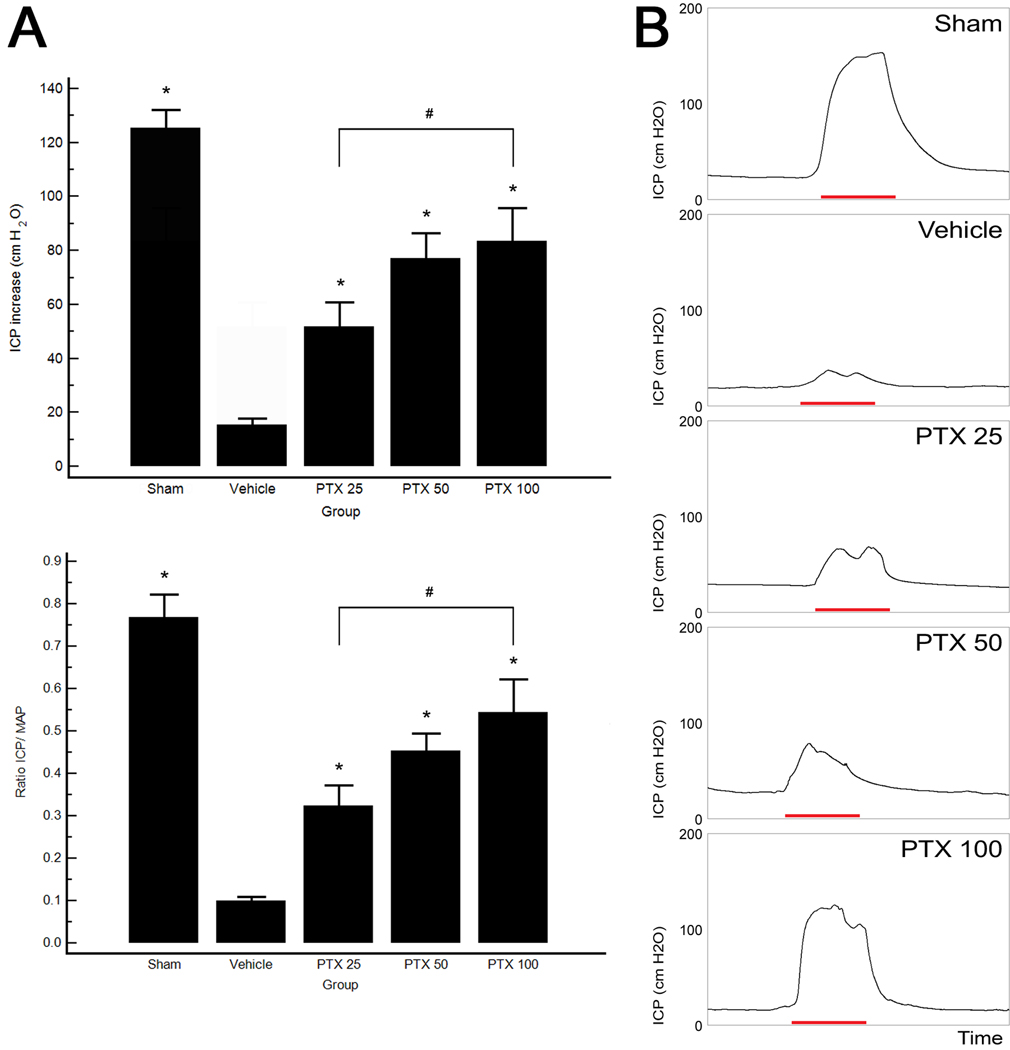

The effects of daily oral PTX treatment on recovery of erectile function are shown in Figure 1. CN crush injury consistently resulted in ED, as is illustrated by the significant decrease in the ICP-to-MAP ratio in the vehicle-treated group (0.09 ± 0.01) compared to sham animals (0.77 ± 0.05). Partial but significant recovery of erectile response was seen in all PTX-treated groups. A significant difference (p = 0.0337) was observed between the PTX 25 (0.32 ± 0.05) and PTX 100 (0.54 ± 0.08) groups, whereas PTX 50 (0.45 ± 0.04) was not significantly different from the lowest and highest doses. MAP did not differ significantly among groups (p = 0.59).

Fig. 1.

Electrostimulation of cavernous nerves at 4 wk. (a) Top: the effects of chronic treatment with pentoxifylline (PTX) in increasing dosages on the increase of intracavernous pressure (ICP) on electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerve. Bottom: ratio of ICP to mean arterial pressure (MAP). (b) Representative ICP recordings. The red bar represents an electrical stimulation of the cavernous nerve with a duration of 50 s.

* p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated rats.

# p < 0.05.

3.2. Histomorphometric analysis

3.2.1. Nerve regeneration

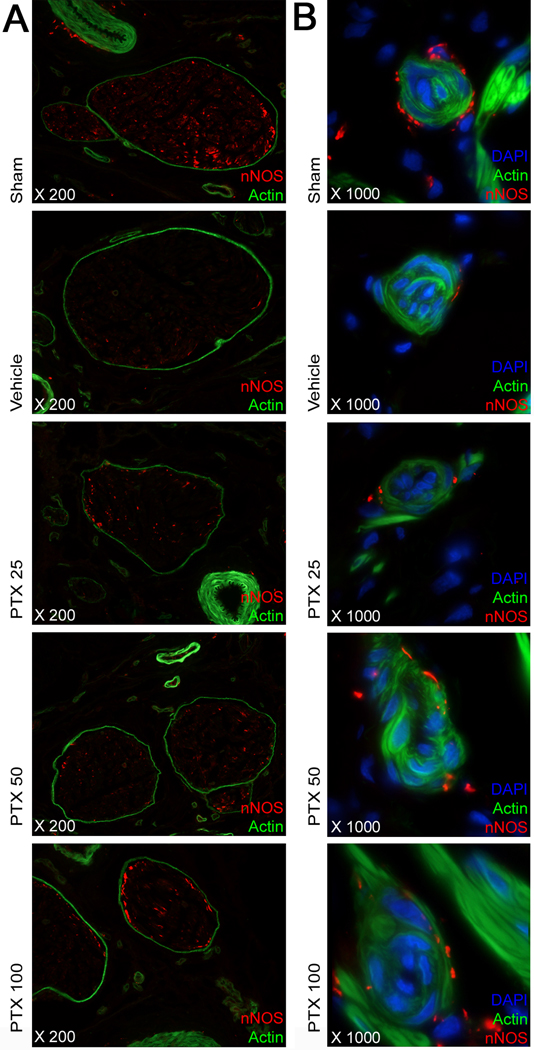

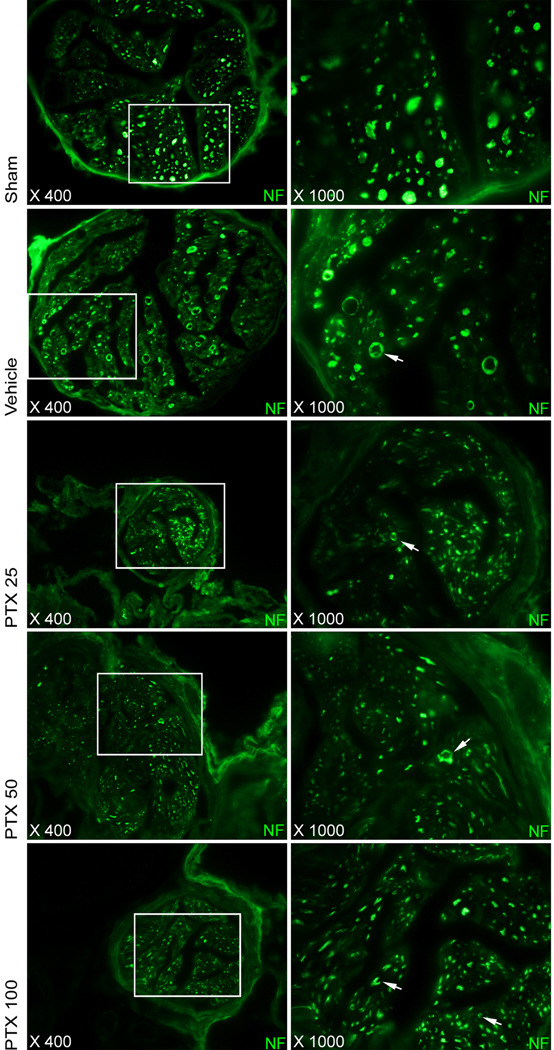

Regeneration of neuronal NOS (nNOS)–positive nerves was quantified by histomorphometric analysis of the percentage of the area of the dorsal nerve that stained positive for neuronal-specific NOS. There was a significant decrease in nNOS content of the dorsal penile nerves after bilateral CN crush injury. Following PTX treatment, nNOS content in the dorsal nerves was significantly higher in the PTX 50 and 100 mg/kg per day groups compared with vehicle-treated injured controls (Table 1; Fig. 2a). Similar observations were made for the small nerve fibers accompanying the helicine artery branches in the erectile tissue, as is illustrated in Figure 2b. In the CN, morphologic changes compatible with Wallerian degeneration, including distortion of overall nerve anatomy, axonal swelling and axonal vacuolization, were observed in the vehicle-treated animals, whereas PTX treatment preserved neural morphology (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Histomorphometric analysis of penile tissue sections†

| Treatment | nNOS content in the dorsal penile nerves, % | Smooth muscle content in corpus cavernosum, % | Collagen content in corpus cavernosum, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 1.13 ± 0.11* | 10.42 ± 0.97* | 32.19 ± 1.71* |

| Vehicle | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 5.02 ± 0.45 | 56.62 ± 3.17 |

| PTX 25 mg/kg per day | 0.62 ± 0.17 | 5.47 ± 0.46 | 40.99 ± 1.53* |

| PTX 50 mg/kg per day | 0.89 ± 0.18* | 7.77 ± 0.64* | 40.02 ± 1.76* |

| PTX 100 mg/kg per day | 1.00 ± 0.25* | 8.55 ± 0.94* | 39.61 ± 2.72* |

nNOS = neuronal nitric oxide synthase; PTX = pentoxifylline.

Histomorphometric digital analysis was performed on tissue sections of the rat penis. NNOS expression was evaluated by determination of the percentage of the dorsal nerve area that stained positive for nNOS. For collagen and smooth muscle content, the positive staining area for the respective tissue was evaluated in the total area within the tunica albuginea. The mean percentage of three tissue sections was included for each animal.

p < 0.05 versus vehicle treatment.

Fig. 2.

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) staining in a penile midshaft specimen. (a) Representative images in each treatment group of the dorsal penile nerves within the dorsal penile neurovascular bundle. Phalloidin staining for actin and immunostaining for nNOS. Original magnification: ×200. (b) High-power images of the helicine neurovascular bundles in the corpus cavernosum in each treatment group. Note the near-complete absence of small nerve fibers expressing nNOS surrounding the helicine arteries following cavernous nerve crush and the preservation of these in animals treated with pentoxifylline (PTX). Sections stained for nNOS, actin and DAPI. Original magnification: ×1000.

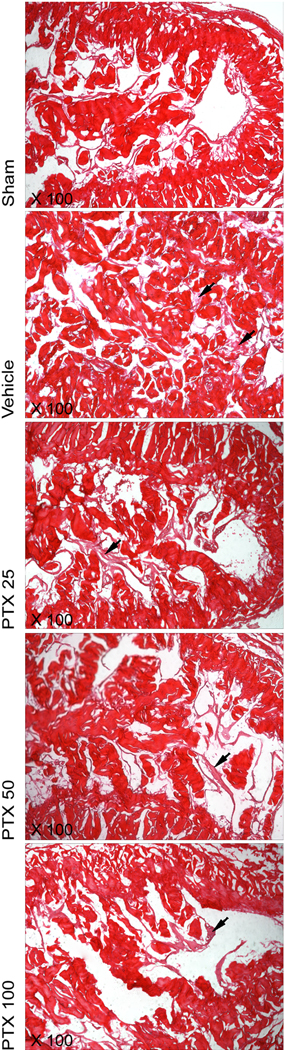

Fig. 3.

Neurodegeneration in the cavernous nerve distal to the crush injury. Note microanatomic signs of Wallerian degeneration, including an overall distortion of normal nerve anatomy, axonal swelling and axonal vacuolization (arrows) in the vehicle treated group. Further note an increased number of small axons in the pentoxifylline (PTX) treated groups, indicative of nerve regeneration. Sections were immunostained for neurofilament. Original magnification: ×400, ×1000.

3.2.2. Smooth muscle cell and collagen content in the corpus cavernosum

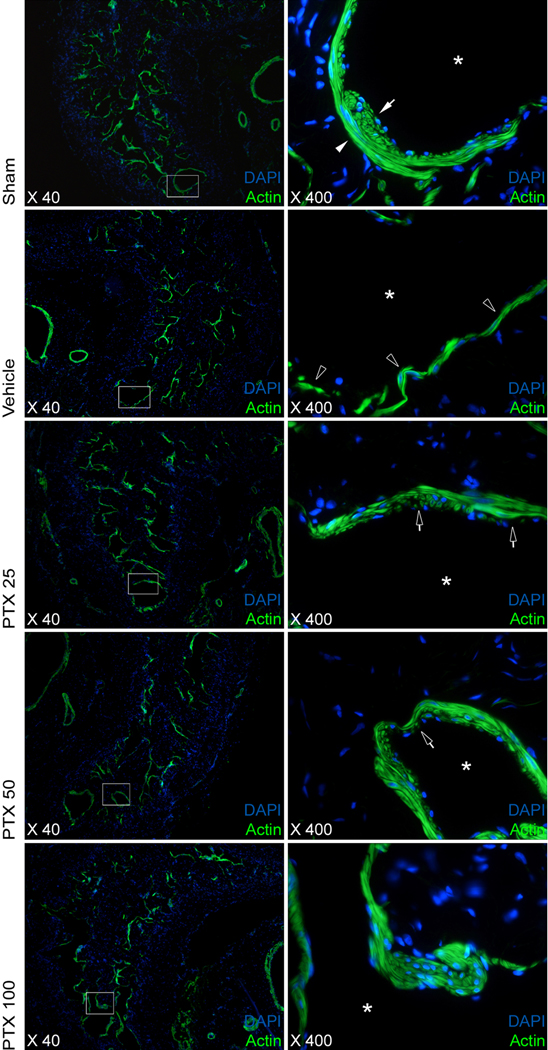

Consistent with previous observations, SMC volumetric density in the corpus cavernosum following CN crush and vehicle treatment declined to approximately half the content compared to those animals who underwent a sham procedure. SMC content in the PTX 50 and PTX 100 groups, but not in the PTX 25 group, was significantly higher than in vehicle treated rats (table 1). Loss of smooth muscle content was attributable to a loss of SMCs in both the circular layer and the longitudinal layer lining the cavernous sinusoids, with the loss of SMCs appearing more pronounced in the longitudinal cell layer after injury. Chronic PTX treatment resulted in partial restoration of smooth muscle architecture (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Changes in the architecture of the corpus cavernosum: smooth muscle. Images showing detailed changes in the structure of cavernous smooth muscle surrounding sinusoids (asterisk). The left panel shows an overview of one side of the corpus cavernosum. The sinus indicated by the white box is depicted in high magnification in the right panel. Loss of smooth muscle structure was more pronounced in the longitudinal, or inner, layer of smooth muscle cells (closed arrows) rather than the circular, or outer, layer (closed arrowheads). Open arrowheads: Architectural changes in the such as a decrease in cell number in both layers were observed. Chronic pentoxifylline (PTX) treatment resulted in partial restoration of smooth muscle architecture (open arrows). Phalloidin staining for actin and nuclear staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Original magnification: ×40, ×400.

PTX treatment resulted in less collagen deposition in all treatment groups compared to the vehicle-treated rats. Fibrosis was present following CN injury, as indicated by the increase in collagen staining in vehicle-treated rats compared with sham animals. However, no dose dependency for collagen content in the corpus cavernosum was observed, and the improvement compared to vehicle treatment was virtually identical in all three treatment groups (Table 1). Histologically, deposition of collagen following CN crush injury was mainly attributable to deposits of thin, subendothelial reticulin fibers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Changes in the architecture of the corpus cavernosum: collagen. Overview of collagen content in the middle corpus cavernosum. Collagen is located mainly in the trabeculae and the tunica albuginea where it consists of thick, bright red bundles. Reticular collagen fibers further are visible as thin fibrils forming a subendothelial meshwork. Note the deposition of reticular collagen in the sinusoids following crush injury (black arrows); this was partially prevented by pentoxifylline (PTX) treatment. Sections were stained with picrosirius red stain. Original magnification: ×200.

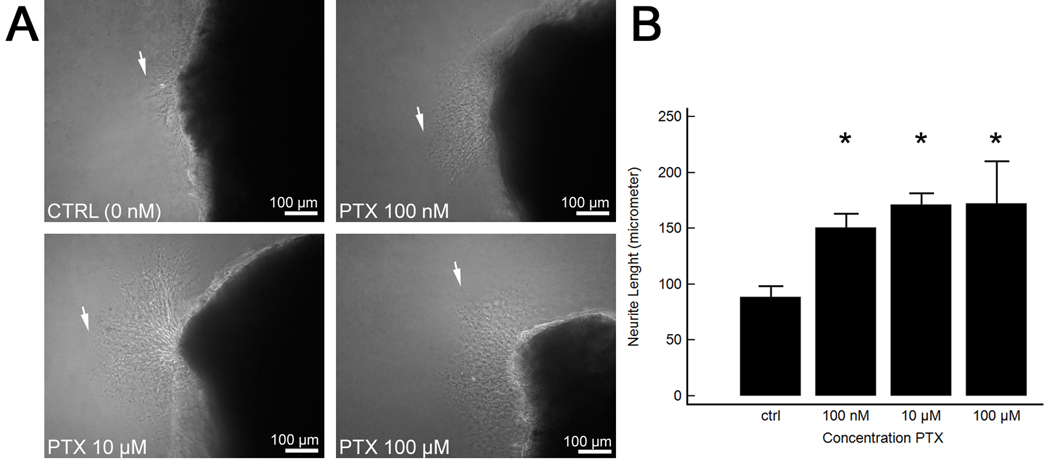

3.2.3. Major pelvic ganglion culture

MPG culture was used to investigate the direct neurotrophic effects of PTX because enhanced in vivo neuroregeneration in PTX treated rats was observed. After 48 h of tissue culture, there was a significantly increased length of neurite outgrowth in the PTX-treated MPG fragments compared with nontreated controls (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Culture of the major pelvic ganglion (MPG) and evaluation of neurite sprouting in vitro. (a) Representative images of inverted microscopy of the MPG following 48-h culture in medium supplemented with pentoxifylline (PTX) in increasing concentrations. White arrows indicate the longest neurite. The shaded area on the right is a fragment of the dorsocaudal region of the MPG. Note increased length of neurites in the MPG cultures treated with PTX. Original magnification: ×100. (b) Mean neurite length in cultured MPG fragments.

* p < 0.05 versus control group.

4. Discussion

PTX is approved in several countries for the treatment of intermittent claudication and is further used for the treatment of a variety of other diseases including neuropathy, stroke, and various fibrotic conditions [18]. It is gaining acceptance as a conservative treatment for Peyronie’s disease, in which it inhibits TGF-β-mediated collagen deposition and fibrosis in the tunica albuginea [8,12,19]. Furthermore, a recent trial showed beneficial synergistic effects of coadministration of PTX and sildenafil on arterial ED [20]. Clinical availability, a low adverse events profile, direct beneficial effects on erectile function, and high oral bioavailability make PTX an attractive compound for oral penile rehabilitation following RP [18,21]. PTX does not share the risk of FK506, the other well-known immunomodulatory compound that was studied in this setting, which has an immunosuppressive nature that is potentially harmful in men who were previously treated for prostate cancer [2]. PTX also has a well-known safety profile in cases of long-term treatment. In the present study, we report a novel finding of beneficial effects of daily PTX treatment on recovery of erectile function in rats that underwent CN injury, thereby simulating postprostatectomy ED.

Wallerian degeneration following nerve injury is characterized by degradation of the axoplasm and axolemma, accompanied by development of axonal and myelin debris that is subsequently removed by Schwann cells and invading macrophages [22]. TNF-α and TGF-β are important cytokines in orchestrating the inflammatory response in the nerve and its close surroundings that accompanies Wallerian degeneration. Both cytokines are distinctively upregulated in the endo- and epineurium shortly after peripheral nerve injury [14,22]. Blocking pathways of proinflammatory cytokines to modulate the inflammatory response has been shown to be beneficial in peripheral nerve regeneration: Various studies have shown advantageous effects on nerve regeneration and perineural scar formation following axotomy, either by neutralizing TNF-α and TGF-β signaling pathways by antibodies or in animal models in which the respective signaling pathways were genetically knocked down [15,17,23,24]. PTX interferes in both cytokine pathways and has been used to improve nerve regeneration in TNF-α-mediated axonal degeneration in the rabbit optic nerve [11]. It further stimulates myelin uptake by macrophages, thereby supporting a more efficient axonal regeneration by removing myelin-derived axonal outgrowth inhibitors [11,25]. Aside from having these immunomodulatory properties, PTX has been identified as a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor whose action results in an increase of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) but not cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels [26]. Because elevation of cAMP has been shown to be neurotrophic [27], it is likely that PTX possesses indirect neurotrophic effects. In this study, we show that PTX attenuated the hallmark anatomic changes of Wallerian degeneration distal to the nerve injury site. Furthermore, the expression of nNOS in the dorsal nerves was preserved after PTX treatment compared with vehicle-treated rats. The neurotrophic effects of PTX were confirmed in vitro, as demonstrated by the enhanced neurite outgrowth in the MPG culture at concentrations reached in human plasma when PTX is administered three times daily in the 400-mg extended-release formulation [21].

It has been hypothesized that the absent or decreased capacity for penile erection following CN injury results in a hypoxia-induced release of TGF-β in the corpus cavernosum, which in turn leads to fibrosis and SMC apoptosis in the erectile tissue [6,28]. In line with these findings, inhibition of the TGF-β pathway resulted in a significant decrease of collagen deposition and apoptosis in the corpus cavernosum following bilateral CN injury [5,7]. Similar beneficial effects on fibrosis and apoptosis have been shown after long-term treatment with phosphodiesterase inhibitors following CN injury [29]. Based on the above-mentioned observations, it is possible that PTX has salutary effects on SMC preservation and fibrosis prevention due to inhibitory actions on TGF-β and phosphodiesterase. In line with this hypothesis, our group has previously shown in vitro that PTX was able to reduce collagen formation in penile fibroblasts cultured in the presence of TGF-β [8,12]. In addition, a similar observation was made in TGF-β-pretreated vascular SMCs [26]. In the present study, PTX treatment resulted in decreased collagen deposition in the corpus cavernosum. Furthermore, PTX treatment resulted in preservation of SMC architecture and content.

The dosages of PTX used in this study were based on various previous studies in rat models and on a dose calculation based on the current human recommended dose. In rats, the plasma half-life was 0.6 h and the oral bioavailability was 100%, which is similar to the pharmacokinetics in human subjects [30]. The maximum recommended dose on a body-surface-area basis, as stated by the US Food and Drug Administration, is 137 mg/kg in rats [31]. When translated to human dosages on body-surface-area based formula, the dosages would be 239 mg/d (PTX 25), 567 mg/d (PTX 50), and 1134 mg/d (PTX 100) in a human male subject weighing 70 kg. [32]. The latter dose roughly is equivalent to the currently used human dose of 3 × 400 mg/d. In human subjects, the apparent plasma half-life of PTX varies from 0.4 to 0.8 h and the plasma half-lives of its metabolites vary from 1 to 1.6 h [31]. In older patients (60–68 yr), the elimination rate can be somewhat lower, which might even have beneficial implications for the RP patient. Furthermore, because the extended-release formulation is available, the dosage of PTX possibly can be lowered compared to the dosages we used in rats; maintaining high plasma levels over longer periods of time putatively potentiates the efficacy of the drug.

This study has limitations. Although PTX treatment has beneficial effects on both nerve regeneration and preservation of corpus cavernosum microarchitecture, the main cytokine pathways remain poorly defined. In addition, this study investigated only short-term PTX treatment on erectile function. Long-term administration of PTX might enhance nerve regeneration to a larger degree, resulting in further improved erectile function. Experiments relating to these issues have recently been initiated in our laboratory.

5. Conclusions

In this study, daily oral PTX treatment following CN crush injury resulted in a restoration of erectile function. The underlying mechanisms of recovery appear to involve enhanced nerve regeneration as well as a preservation of the microarchitecture of the erectile tissue in the corpus cavernosum. The clinical availability of PTX merits application in penile rehabilitation studies following RP in the near future.

Take-home message

Pentoxifylline enhances erectile recovery in a rat model of cavernous nerve crush injury by improving nerve regeneration and ameliorating architectural changes in the corpus cavernosum. Its clinical availability merits application in the near future for penile rehabilitation following radical prostatectomy.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: This work was funded by NIDDK/NIH R37 DK045370.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: Tom F. Lue had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Albersen, Lue.

Acquisition of data: Albersen, Fandel, Zhang, Banie, Lin G.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Albersen, Fandel, Lin G, Lin CS, Lue, De Ridder.

Drafting of the manuscript: Albersen, Fandel.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: De Ridder, Lin CS, Lue.

Statistical analysis: Albersen.

Obtaining funding: Albersen, De Ridder, Lue.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Banie.

Supervision: De Ridder, Lin CS, Lue.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: I certify that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/ affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Maarten Albersen is a fellow of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) and a scholar of the European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO), the Federico Foundation, and Belgische Vereniging voor Urologie (BVU), and he received an unrestricted research grant from Bayer Healthcare Belgium.

References

- 1.Walz J, Burnett AL, Costello AJ, et al. A critical analysis of the current knowledge of surgical anatomy related to optimization of cancer control and preservation of continence and erection in candidates for radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2010;57:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sezen SF, Lagoda G, Burnett AL. Role of immunophilins in recovery of erectile function after cavernous nerve injury. J Sex Med. 2009;6(Suppl 3):340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bella AJ, Lin G, Tantiwongse K, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) acts primarily via the JAK/STAT pathway to promote neurite growth in the major pelvic ganglion of the rat: Part I. J Sex Med. 2006;3:815–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albersen M, Fandel TM, Lin G, et al. Injections of adipose tissue-derived stem cells and stem cell lysate improve recovery of erectile function in a rat model of cavernous nerve injury. J Sex Med. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01875.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canguven O, Lagoda G, Sezen SF, Burnett AL. Losartan preserves erectile function after bilateral cavernous nerve injury via antifibrotic mechanisms in male rats. J Urol. 2009;181:2816–2822. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albersen M, Joniau S, Claes H, Van Poppel H. Preclinical evidence for the benefits of penile rehabilitation therapy following nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Adv Urol. 2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/594868. 594868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fandel TM, Bella AJ, Lin G, et al. Intracavernous growth differentiation factor-5 therapy enhances the recovery of erectile function in a rat model of cavernous nerve injury. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1866–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin G, Shindel AW, Banie L, et al. Pentoxifylline attenuates transforming growth factor-beta1-stimulated elastogenesis in human tunica albuginea-derived fibroblasts part 2: interference in a TGF-beta1/Smad-dependent mechanism and downregulation of AAT1. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1787–1797. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei T, Sabsovich I, Guo TZ, et al. Pentoxifylline attenuates nociceptive sensitization and cytokine expression in a tibia fracture rat model of complex regional pain syndrome. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zabel P, Schade FU, Schlaak M. Inhibition of endogenous TNF formation by pentoxifylline. Immunobiology. 1993;187:447–463. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrovich MS, Hsu HY, Gu X, Dugal P, Heller KB, Sadun AA. Pentoxifylline suppression of TNF-alpha mediated axonal degeneration in the rabbit optic nerve. Neurol Res. 1997;19:551–554. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1997.11740856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shindel AW, Lin G, Ning H, et al. Pentoxifylline attenuates transforming growth factor-beta1-stimulated collagen deposition and elastogenesis in human tunica albuginea-derived fibroblasts part 1: impact on extracellular matrix. J Sex Med. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01790.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Salam OM, Baiuomy AR, El-Shenawy SM, Arbid MS. The anti-inflammatory effects of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor pentoxifylline in the rat. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taskinen HS, Ruohonen S, Jagodic M, Khademi M, Olsson T, Roytta M. Distinct expression of TGF-beta1 mRNA in the endo- and epineurium after nerve injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:969–975. doi: 10.1089/0897715041526131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nath RK, Kwon B, Mackinnon SE, Jensen JN, Reznik S, Boutros S. Antibody to transforming growth factor beta reduces collagen production in injured peripheral nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1100–1106. discussion 1107–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiefer R, Streit WJ, Toyka KV, Kreutzberg GW, Hartung HP. Transforming growth factor-beta 1: a lesion-associated cytokine of the nervous system. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1995;13:331–339. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(94)00074-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkins S, Smith KG, Loescher AR, Boissonade FM, Ferguson MW, Robinson PP. The effect of antibodies to TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta2 at a site of sciatic nerve repair. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2006.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frampton JE, Brogden RN. Pentoxifylline (oxpentifylline). A review of its therapeutic efficacy in the management of peripheral vascular and cerebrovascular disorders. Drugs Aging. 1995;7:480–503. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199507060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payton S. Therapeutic benefit of pentoxifylline for Peyronie’s disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:237. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozdal OL, Ozden C, Gokkaya S, Urgancioglu G, Aktas BK, Memis A. The effect of sildenafil citrate and pentoxifylline combined treatment in the management of erectile dysfunction. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:133–136. doi: 10.1007/s11255-007-9255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beermann B, Ings R, Mansby J, Chamberlain J, McDonald A. Kinetics of intravenous and oral pentoxifylline in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;37:25–28. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenrich K, Gordon T. Canadian association of neuroscience review: Axonal regeneration in the peripheral and central nervous systems—current issues and advances. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004;31:142–156. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100053798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siebert H, Bruck W. The role of cytokines and adhesion molecules in axon degeneration after peripheral nerve axotomy: a study in different knockout mice. Brain Res. 2003;960:152–156. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03806-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stegmuller J, Huynh MA, Yuan Z, Konishi Y, Bonni A. TGFbeta-Smad2 signaling regulates the Cdh1-APC/SnoN pathway of axonal morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1961–1969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3061-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liefner M, Maruschak B, Bruck W. Concentration-dependent effects of pentoxifylline on migration and myelin phagocytosis by macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;89:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YM, Wu KD, Tsai TJ, Hsieh BS. Pentoxifylline inhibits PDGF-induced proliferation of and TGF-beta-stimulated collagen synthesis by vascular smooth muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:773–783. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borin A, Toledo RN, Ho PL, Testa JR, Cruz OL, Fukuda Y. Influence of cyclic AMP on facial nerve regeneration in rats. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74:675–683. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31376-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leungwattanakij S, Bivalacqua TJ, Usta MF, et al. Cavernous neurotomy causes hypoxia and fibrosis in rat corpus cavernosum. J Androl. 2003;24:239–245. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrini MG, Davila HH, Kovanecz I, Sanchez SP, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF, Rajfer J. Vardenafil prevents fibrosis and loss of corporal smooth muscle that occurs after bilateral cavernosal nerve resection in the rat. Urology. 2006;68:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hui YH, Huang NH, Ebbert L, et al. Pharmacokinetic comparisons of tail-bleeding with cannula- or retro-orbital bleeding techniques in rats using six marketed drugs. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2007;56:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. [Accessed September 15, 2010];Pentoxifylline side effects. Drugs.com Web site. http://www.drugs.com/sfx/pentoxifylline-side-effects.html.

- 32.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008;22:659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]