Abstract

Background

Allotetraploids carry pairs of diverged homoeologs for most genes. With the genome doubled in size, the number of putative interactions is enormous. This poses challenges on how to coordinate the two disparate genomes, and creates opportunities by enhancing the phenotypic variation. New combinations of alleles co-adapt and respond to new environmental pressures. Three stages of the allopolyploidization process - parental species divergence, hybridization, and genome duplication - have been well analyzed. The last stage of evolutionary adjustments remains mysterious.

Results

Homoeolog-specific retention and use were analyzed in Arabidopsis suecica (As), a species derived from A. thaliana (At) and A. arenosa (Aa) in a single event 12,000 to 300,000 years ago. We used 405,466 diagnostic features on tiling microarrays to recognize At and Aa contributions to the As genome and transcriptome: 324 genes lacked Aa contributions and 614 genes lacked At contributions within As. In leaf tissues, 3,458 genes preferentially expressed At homoeologs while 4,150 favored Aa homoeologs. These patterns were validated with resequencing. Genes with preferential use of Aa homoeologs were enriched for expression functions, consistent with the dominance of Aa transcription. Heterologous networks - mixed from At and Aa transcripts - were underrepresented.

Conclusions

Thousands of deleted and silenced homoeologs in the genome of As were identified. Since heterologous networks may be compromised by interspecies incompatibilities, these networks evolve co-biases, expressing either only Aa or only At homoeologs. This progressive change towards predominantly pure parental networks might contribute to phenotypic variability and plasticity, and enable the species to exploit a larger range of environments.

Background

An allotetraploid is formed when diploids from two different species, which may have diverged for millions of years, hybridize. The resulting plant, if viable, might have a competitive edge, such as broader ecological tolerance compared to its parents [1-3]. The evolutionary importance of polyploidy, of which allotetraploidy is a common form, is reflected in its prevalence in flowering plants [4]: ancient polyploidy is apparent in all plant genomes sequenced to date and is estimated to have been involved in 15% of all plant speciation events [5]. Furthermore, most cultivated crops have undergone polyploidization during their ancestry [5,6]. Why are polyploids so evolutionarily, ecologically, and agriculturally successful? To answer this question, one has to consider the evolutionary and genetic processes acting at different stages of polyploidization.

Allopolyploidization can be characterized by four distinct stages. Stage 1 is the divergence between parental species, with both species adapting to specific environments and adopting their own mating strategies and reproductive schedules. Directional selection can contribute to the fixation of species-specific beneficial mutations in coding and regulatory regions [7,8], while slightly deleterious mutations are introduced due to drift. In stages 2 and 3, the diverged species hybridize and increase ploidy, with the two events sometimes reversed in order [9]. This change in ploidy enables the correct pairing at meiosis. Hybridization frequently results in phenotypic instability, widespread genomic rearrangements, epigenetic silencing, and unusual splicing [3,10-25]. Newly created polyploids often experience rapid intragenomic adjustments. Stages 2 and 3 are well-studied with artificial polyploids constructed in the laboratory [10,12-17,19,22-24] or spontaneously arising in nature [14,26].

Stage 4 is the long term evolution of homoeologous genes (that is, homologous genes from two parents joined into one polyploid genome and stably inherited). This stage occurs much slower on the evolutionary time-scale and has received considerably less attention, perhaps due to several technical limitations. Sequence analyses have historically required extensive cloning and bioinformatics. Microarrays have had to be specifically designed to distinguish between homoeologs and orthologs. Interesting patterns have been reported, but typically for a few genes [14,27-29]. Notably, the retention and expression of homoeologs is frequently biased towards one parental species. These patterns were reported on a large scale for approximately 1,400 out of 42,000 genes in cotton [30-32], and for dozens in Tragopogon [33]. Recent studies have also discovered abundant genetic variation among independently originated or evolved accessions of Tragopogon [34-36]. What molecular evolutionary processes account for this variation among accessions? How does intraspecific variation in polyploid genomes contribute to phenotypic variation? These questions remain wide open.

Here, we focus on Arabidopsis suecica (As), a highly selfing species [37] found mainly in central Sweden and southern Finland [38]. As originated 12,000 to 300,000 years ago (KYA) from a cross between a largely homozygous ovule-parent Arabidopsis thaliana (At, 2n10) and a pollen-parent Arabidopsis arenosa (Aa, 2n = 16) [39-41]. A single origin of As (2n = 26) has been established with mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNA [39-41]. As originated south of the ice cover and spread north when the ice retreated 10,000 years ago [39]. At is an annual, weedy, and mostly autogamous species native to Europe and central Asia but naturalized worldwide [42]. It has undergone at least two rounds of ancient polyploidization [26] and is annotated with 39 thousand genes. Aa is a self-incompatible member of the Arabidopsis genus, carrying the highest level of genetic diversity among the species group [43]. At and Aa diverged approximately 5 million years ago [44].

One can generate an artificial F1 allotetraploid (F1As) in the lab by performing a cross between a tetraploid At ovule-parent and a tetraploid Aa pollen donor. The resulting primary species hybrid contains two genomes from At and two from Aa. We can use this as an estimate, as the exact haplotypes that contributed to the initial hybridization event are not available, of the genomic composition and homoeolog-specific expression at the time of allopolyploid speciation [24,45,46]. Taking these patterns as reflective of the As ancestral state, we observed how evolution has shaped the As genome. As At is a selfer and Aa an outcrosser, At-originated homoeologs might have possessed more deleterious mutations due to Hill-Robertson interference [47]. Are Aa-originated homoeologs more commonly retained? At and Aa evolved orthologous networks in which genes were finely tuned to coordinate, separately within each species. Interference of At and Aa homoeologs may cause mis-regulation within mixed As networks. This is akin to Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities [48]. Do heterologous networks evolve to restore their original orthologous-like compositions? Here, we address these and other questions.

Results

For every gene in As, we set to determine whether both At and Aa homoeologs are present in the genome and whether they are expressed evenly or in homoeolog-specific fashion [49]. With the genome-wide Arabidopsis tiling microarray, we scanned the genomes of At, Aa, As, and F1As. We analyzed the transcriptome of As with tiling arrays and validated results with Illumina resequencing. We assembled a statistical pipeline to identify At and Aa homoeolog-originated signals, and to estimate their contribution to the As populations of DNA and RNA.

Comparison of probe hybridization between parental species, and between As and F1As

The Arabidopsis array features 3.2 million 25-base-long probes tiled throughout the complete genome at a 35-base distance. As these features are homologous to the At reference, they should, on average, exhibit a lower hybridization with Aa DNA. Probe intensities confirm this expectation. Two typical examples are shown for chromosomes 3 and 4 (Figures 1 and 2; see Additional files 1, 2, 3,4, 5 and 6 for other examples). F1As signals are a sharp intermediate between At and Aa. As shows remarkable correspondence with F1As, with the exception of several extended regions. We hypothesize that these regions correspond to historic losses of homoeologous chromosomal regions in As.

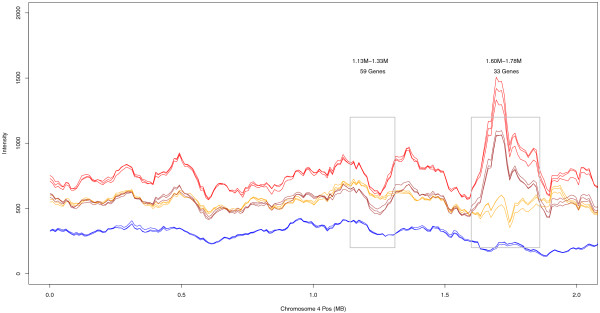

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution of probe intensities. The 100-kb sliding window averages for At (red), Aa (blue), As (gold), and F1As (brown) on chromosome 4. Chromosome positions and gene annotations correspond to the At genome. Gray boxes indicate clusters containing at least 30 genes with a strong unidirectional bias, where at least 27 genes have the same bias, and significant for at least 9 genes. A list of clusters can be found in Table 1. Genes within these clusters can be found in Additional file 2.

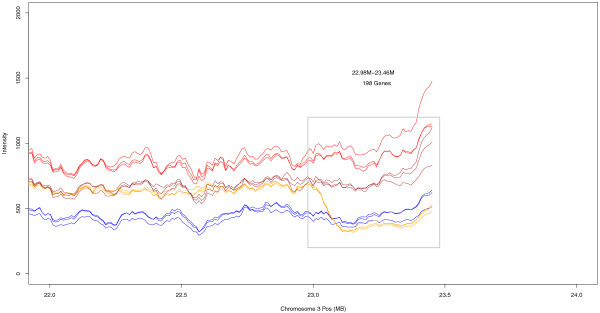

Figure 2.

Chromosome distribution of probe intensities. The 100-kb sliding window averages for At (red), Aa (blue), As (gold), and F1As (brown) on chromosome 3.

We mapped features onto the genes and compared intensities between As and F1As; 6,790 genes exhibited differential hybridization (Wilcoxon ranked sum test, false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05). To identify large putative alterations, we scanned for clusters containing at least 30 genes with a strong unidirectional bias (at least 27 with the same bias, significant for at least 9 genes). We identified 39 clusters, encompassing 1,643 genes (Table 1). Some clusters were due to differential abundance of transposable-element-like sequences. Chr1 13.66 M, Chr1 14.00 M, Chr3 12.44 M, Chr3 13.36 M, and Chr5 11.06 M mainly consisted of copia-like, gypsy-like, or CACTA-like retrotransposons. Other regions - for instance, on Chr1 0.29 M, Chr3 0.30 M, Chr3 5.58 M, Chr3 21.60 M, and Chr3 22.98 M - appeared free from this problem (Additional file 2 includes detailed information). Interestingly, the region 1.60 M-1.78 M on chromosome 4 (Figure 1) is coincident with the heterochromatic knob known to be hypervariable in At [50]. The 22.98 M-23.46 M region of chromosome 3 (Figure 2) looked like an At-homoeolog deletion. These results show that tiling arrays can be a useful tool for detecting copy number variation [51] and large-scale alterations in the As genome. As these analyses are based on non-normalized signals (between species), they are likely error-prone for individual genes.

Table 1.

Regions of putative alterations in Arabidopsis suecica

| Chromosome | Region | Number of genes | Percent with differential hybridization | Percent TEs | Number of probes | Higher hybridization in? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1 | 0.29 M-0.39 M | 38 | 44.7 | 0 | 2,537 | F 1 As |

| 0.82 M-0.91 M | 32 | 28.1 | 3.1 | 2,266 | F 1 As | |

| 3.16 M-3.29 M | 43 | 37.2 | 0 | 3,175 | As | |

| 8.40 M-8.49 M | 37 | 29.7 | 2.7 | 1,991 | F 1 As | |

| 13.66 M-13.86 M | 43 | 58.1 | 51.2 | 3,547 | F 1 As | |

| 14.00 M-14.39 M | 70 | 42.9 | 51.4 | 5,998 | F 1 As | |

| 29.97 M-30.07 M | 40 | 32.5 | 0 | 2,536 | F 1 As | |

| AT2 | 1.96 M-2.03 M | 34 | 32.4 | 8.8 | 1,377 | As |

| 4.57 M-4.69 M | 30 | 30.0 | 36.7 | 2,302 | F 1 As | |

| 6.50 M-6.67 M | 43 | 27.9 | 16.3 | 3,214 | As | |

| 10.88 M-11.01 M | 38 | 26.3 | 0 | 3,182 | As | |

| 14.74 M-14.84 M | 37 | 27.0 | 0 | 2,440 | F 1 As | |

| 19.60 M-19.68 M | 36 | 38.9 | 0 | 2,065 | F 1 As | |

| AT3 | 0.30 M-0.36 M | 33 | 42.4 | 0 | 1,568 | F 1 As |

| 5.58 M-5.68 M | 32 | 46.9 | 0 | 2,299 | As | |

| 7.30 M-7.38 M | 31 | 32.3 | 16.1 | 1,822 | F 1 As | |

| 12.44 M-12.61 M | 36 | 27.8 | 61.1 | 3,055 | F 1 As | |

| 13.36 M-13.50 M | 34 | 55.9 | 50.0 | 2,431 | As | |

| 14.55 M-14.70 M | 39 | 38.5 | 33.3 | 2,904 | As | |

| 20.25 M-20.34 M | 31 | 32.3 | 3.2 | 2,165 | F 1 As | |

| 20.93 M-21.00 M | 30 | 30.0 | 0 | 1,881 | F 1 As | |

| 21.30 M-21.43 M | 44 | 34.1 | 2.3 | 3,227 | F 1 As | |

| 21.60 M-21.73 M | 45 | 44.4 | 0 | 3,217 | F 1 As | |

| 22.11 M-22.22 M | 37 | 29.7 | 0 | 2,520 | F 1 As | |

| 22.98 M-23.46 M | 198 | 79.8 | 2.0 | 12,309 | F 1 As | |

| AT4 | 1.13 M-1.33 M | 59 | 28.8 | 1.7 | 4,967 | As |

| 1.60 M-1.78 M | 33 | 57.6 | 39.4 | 2,762 | F 1 As | |

| 7.59 M-7.68 M | 34 | 29.4 | 2.9 | 2,052 | As | |

| 7.67 M-7.82 M | 47 | 23.4 | 21.3 | 3,232 | As | |

| 16.89 M-16.96 M | 32 | 34.4 | 0 | 1,797 | As | |

| 17.86 M-17.95 M | 39 | 38.5 | 0 | 2,000 | F 1 As | |

| AT5 | 9.92 M-10.11 M | 44 | 43.2 | 22.7 | 4,269 | As |

| 11.06 M-11.27 M | 42 | 45.2 | 59.5 | 2,948 | F 1 As | |

| 13.76 M-13.89 M | 38 | 36.8 | 18.4 | 2,785 | As | |

| 18.49 M-18.61 M | 33 | 30.3 | 0 | 2,882 | As | |

| 20.53 M-20.70 M | 34 | 29.4 | 2.9 | 2,621 | As | |

| 23.48 M-23.56 M | 33 | 30.3 | 0 | 1,991 | F 1 As | |

| 26.41 M-6.47 M | 34 | 29.4 | 0 | 1,453 | F 1 As | |

| ATM | 0.02 M-.24 M | 30 | 50.0 | 0 | 1,447 | F 1 As |

As, Arabidopsis suecica; F1As, F1 artificial allotetraploid.

Homoeolog-specific retention

To analyze the homoeolog-specific retention and expression of individual genes, we focused on 1,393,557 probes mapping to coding regions using Bowtie [52]. Since Aa and At sequences differ at 1 out of 20 bases, some 25-base oligonucleotides designed for At are a perfect match for Aa sequences. Whenever orthologous Aa sequences mis-match to the At chip, this hybridization is weakened (hereafter termed 'diagnostic features' (DFs)). Separately for every gene, we identified a scaling factor based on probes with similar signatures of hybridization to normalize intensities between species. We then identified homoeolog-specific DFs and only retained those (405,466) robust over replicates (Figure 3). We could only follow 24,344 genes as the fastest-evolving genes have too many DFs for normalization (Additional file 3).

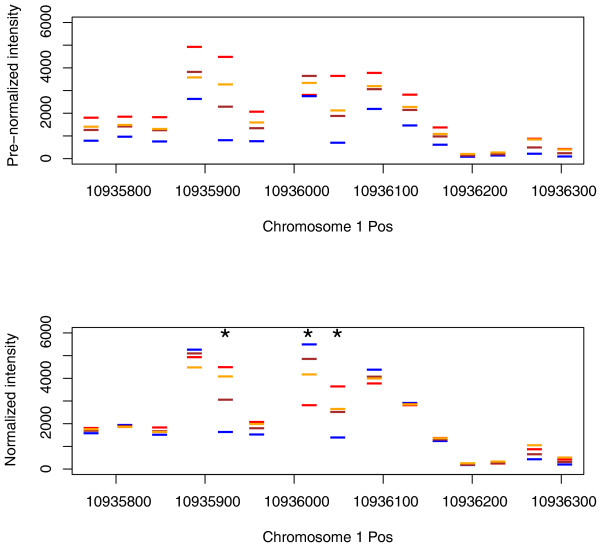

Figure 3.

Probe intensities before and after normalization. Probe intensities for every gene were normalized to identical levels in all arrays. A t-test between At (red) and Aa (blue) replicates identified diagnostic features (shown with asterisks) that were used to identify homoeolog-specific hybridization. F1As (brown) is shown as a null reference for which to compare As (gold).

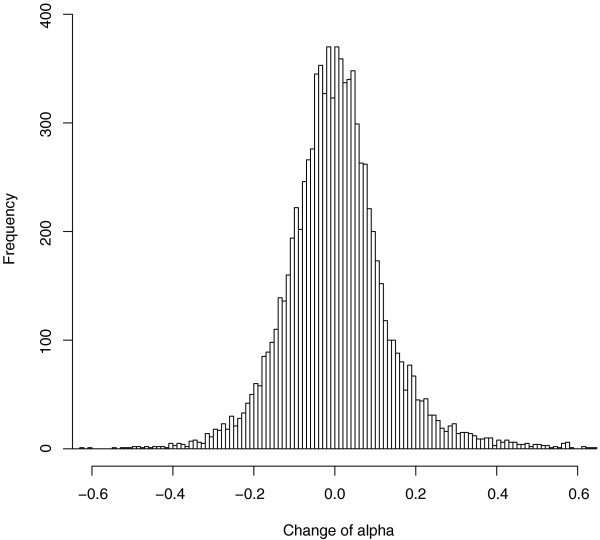

We tested for deviations from an equal representation of the two homoeologs in the As genome [12,16,53]. As a reference point, we used the F1As DNA in which homoeologs are present at equal doses (Figure 1). For each gene within the regions of putative alterations, we tested for changes in α between As and F1As, where α represents the relative contribution of Aa DF hybridization strengths in a hybrid genome. There was an upward shift in α in As compared to F1As (one-sided paired t-test, P < 2e-17), suggesting a preferential retention of homoeologs derived from the Aa parent (Figure 4). Supporting this, more genes were called Aa-like (614) than At-like (324). This bias is significant, although moderate compared to earlier studies [30-32,34-36]. This might reflect a limited power of microarrays. For instance, we analyzed 30 genes encoded by the mitochondria organelle known to be At-derived. Only one plastid-encoded gene had enough DFs to be unambiguously classified, and was biased towards maternal At, as expected.

Figure 4.

Histogram distribution of homoeolog bias Δα. Δα is shown for the genome of As, using F1As as a null reference. Distribution is nearly symmetrical and centered at 0.004.

Use of At and Aa homoeologs in As transcriptome

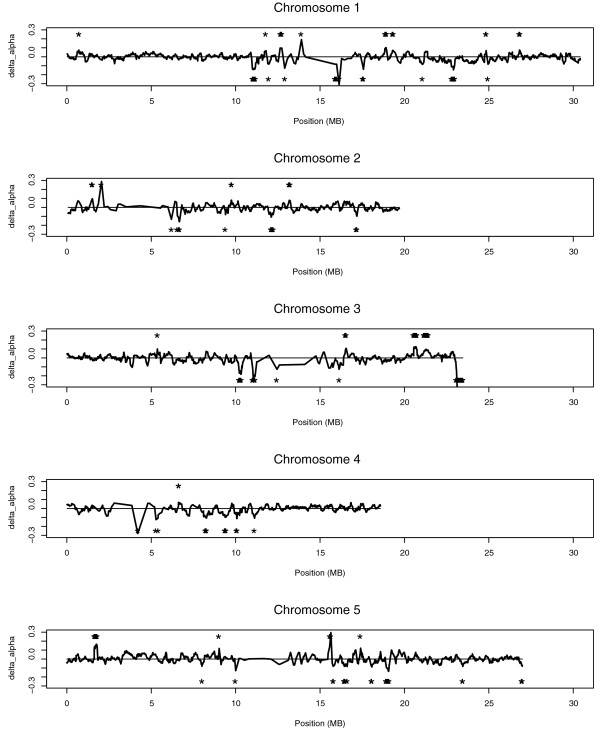

To identify homoeologous transcripts in As, we extracted RNA from leaf tissues and processed microarrays with the SNP-detection protocols similar to above. More than 49% of genes were called expressed, and 7,608 exhibited homoeolog-specific expression, with 3,458 and 4,150 exhibiting At-enriched and Aa-enriched DFs, respectively. Overall, we conclude that, over the 12,000 to 300,000 years, As has accumulated more deletions of At-originated homoeologs and uses the remaining At-originated homoeologs somewhat less (Table 2). Genes physically clustered together might co-express and co-evolve in transcript levels, as previously observed in flies [54]. To test whether biases in homoeolog-specific expression were concordant between nearby genes, we calculated running averages of Δα along chromosomes (Figure 5), and found regions with clusters of At-enriched and Aa-enriched transcription.

Table 2.

Homoeolog-specific retention and use in Arabidopsis suecica

| Classification | As genome | As transcriptome |

|---|---|---|

| At-like | 324 | 3,458 |

| Aa-like | 614 | 4,150 |

Aa, Arabidopsis arenosa; As, Arabidopsis suecica; At, Arabidopsis thaliana.

Figure 5.

Chromosomal distribution of clusters of biased homoeolog transcripts. Lines above the center indicate clusters of At-like genes, and those below indicate of Aa-like genes. Asterisks depict significance using a genome-wide permutation test. Presence of another asterisk indicates a nearby region that is also clustered with At- or Aa-enriched transcription.

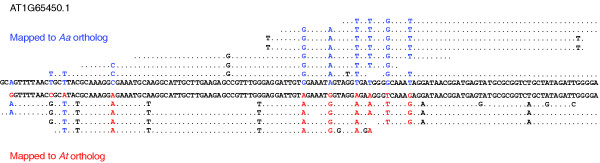

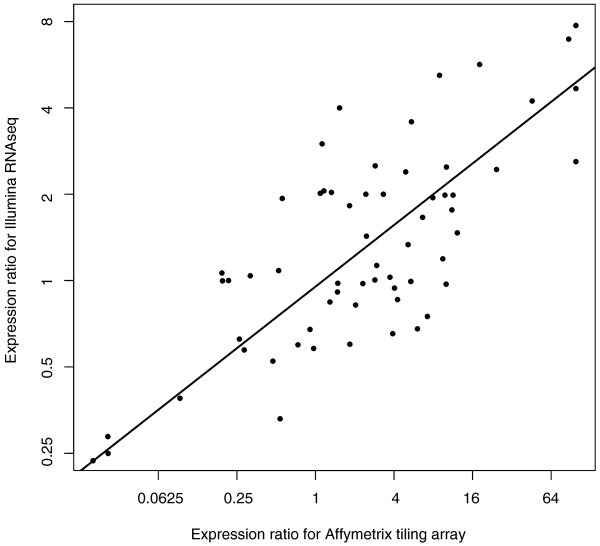

To validate the tiling array-based procedures above, we prepared Illumina libraries and performed RNA-sequencing of the As transcriptome. The Aa genome is not yet assembled, but we identified 52 Aa genes from GenBank and acquired an additional 50 genes from the UC Genome Center. We identified the orthologous At genes for these Aa genes and mapped the Illumina reads to both homologs. Nine genes did not contain any reads that were mapped to either homolog. For 14 genes, reads only mapped to either the Aa or the At reference. For the remaining genes, reads were aligned to both homologs and clustered as either derived from At or Aa (Figure 6). We consider the number of uniquely mapped reads as a measure of homoeolog-specific expression. A strong correlation in Aa:At expression ratio between tiling arrays and the RNA-seq (R2 = 0.646, P < 5e-07) proves that both approaches work. This concordance is very satisfactory (Figure 7) given that RNA samples were extracted from independently grown plants, and that microarray estimates are frequently noisy.

Figure 6.

Sequenced read alignments to At and Aa orthologs. Orthologous At and Aa sequences shown at center contain diagnostic SNPs in red and blue, respectively, that can be used to align and cluster Illumina reads.

Figure 7.

Concordance between homoeolog-specific expression estimated from At tiling microarray (X-axis) and Illumina resequencing (Y-axis). R2 = 0.646, P < 5e-07.

Network analyses of homoeolog-specific genes

The summary of the Gene Ontology analysis of genes exhibiting homoeolog-specific retention and expression is shown in Tables 3 and 4. The categories 'cell communication' and 'signal transduction' were underrepresented, while 'DNA repair' and 'response to DNA damage stimulus' were overrepresented. Aa-enriched transcripts were overrepresented in the 'gene expression' category, including subprocesses involved in transcription, translation, RNA processing and gene silencing by miRNA.

Table 3.

Gene Ontology annotation for homoeolog-biased genes in the Arabidopsis suecica genome, overrepresented unless stated

| Classification | Biological process | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| At-like | Sulfur amino acid metabolic process | 0.00078 |

| Response to fungus | 0.0054 | |

| Heat acclimation | 0.0054 | |

| Aspartate family amino acid metabolic process | 0.012 | |

| mRNA metabolic process | 0.012 | |

| Riboflavin biosynthetic process | 0.013 | |

| Membrane lipid metabolic process | 0.013 | |

| Cellular sodium ion homeostasis | 0.013 | |

| Cellular calcium ion homeostasis | 0.021 | |

| Aspartate family amino acid metabolic process | 0.024 | |

| Purine ribonucleoside monophosphate metabolic process | 0.035 | |

| Cellular potassium ion homeostasis | 0.036 | |

| Aa-like | Protein amino acid glycosylation | 0.021 |

| Defense response, underrepresented | 0.029 | |

| DNA repair | 0.024 | |

| Response to DNA damage stimulus | 0.024 | |

| RNA metabolic process | 0.028 | |

| Cell communication, underrepresented | 0.031 | |

| Signal transduction, underrepresented | 0.033 | |

| Hormone transport | 0.044 | |

| Microtubule cytoskeleton organization | 0.044 |

Table 4.

Gene Ontology annotations for homoeolog-biased use (expression) in Arabidopsis suecica transcriptome, overrepresented unless stated

| Classification | Biological process | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| At-like | One-carbon metabolic process | 6.1e-05 |

| Intracellular protein transport | 0.00012 | |

| Macromolecule localization | 0.00012 | |

| Microtubule-based movement | 0.00045 | |

| Cytoskeleton-dependent intracellular transport | 0.00045 | |

| Protein complex assembly | 0.0030 | |

| Cellular component organization | 0.0039 | |

| Cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 0.0039 | |

| Photorespiration | 0.0053 | |

| Seryl-tRNA aminoacylation | 0.0069 | |

| Aspartate family amino acid metabolic process | 0.0071 | |

| mRNA metabolic process | 0.011 | |

| Response to drug, underrepresented | 0.020 | |

| Drug transport, underrepresented | 0.020 | |

| Pyrimidine base metabolic process | 0.024 | |

| Phosphate transport | 0.024 | |

| Inflammatory response | 0.024 | |

| Aa-like | Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.0013 |

| ATP synthesis coupled electron transport | 0.0024 | |

| Programmed cell death | 0.0028 | |

| Cell development | 0.0043 | |

| Glycerol metabolic process | 0.0058 | |

| Alcohol metabolic process | 0.0058 | |

| Hormone metabolic process | 0.0058 | |

| Phagocytosis | 0.0081 | |

| Endocytosis | 0.0081 | |

| Hormone catabolic process | 0.012 | |

| Photomorphogenesis | 0.014 | |

| tRNA metabolic process, underrepresented | 0.017 | |

| Transcription | 0.023 | |

| Nuclear transport | 0.031 | |

| Regulation of cell cycle | 0.034 | |

| RNA polyadenylation | 0.034 |

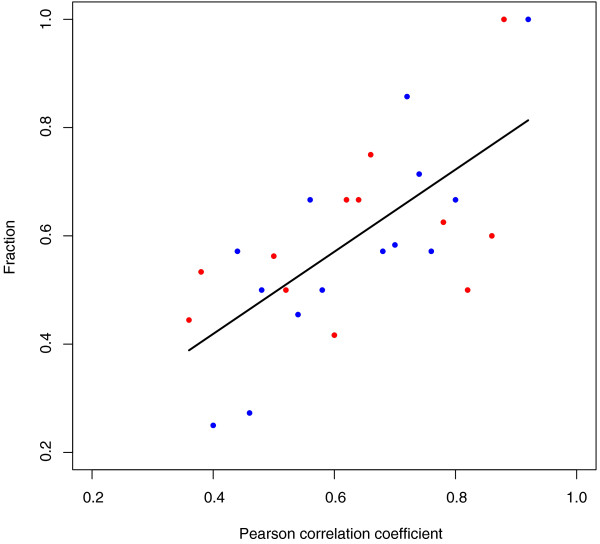

Lastly, we considered homoeolog-specific expression in the context of At transcriptional networks [55]. Of the 7,608 genes, connectedness estimates were available for 6,941 gene pairs. We tested whether bins of higher-connected gene pairs exhibited higher concordance of homoeolog-specific expression (Figure 8). The fraction of concordant pairs was approximately 0.4 in low-connectedness bins, but increased to 0.8 for the high-connected gene pairs (R2 = 0.47, P < 0.0001). We also partitioned networks with homoeolog-specific expressions of at least two genes as co-biased for Aa (325), co-biased for At (219), or with mixed biases (302) (Table 5). The latter 'mixed' group was significantly underrepresented in comparison with random expectation (χ2 test, P < 6e-08).

Figure 8.

Fraction of gene pairs co-biased as either At or Aa for bins of different connectivity. R-squared = 0.47, P < 0.0001. Red dots represent bins with higher fraction of At co-biased genes within bin. Blue dots represent bins with higher fraction of Aa co-biased genes within bin.

Table 5.

Co-biased pairs of Arabidopsis suecica homoeologs in Arabidopsis thalianat-identified gene networks

| Classification | Co-biased as At | Biased as At and Aa | Co-biased as Aa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence | 219 | 302 | 325 |

| Expected | 173.1 | 419.2 | 253.7 |

χ2 test, P < 6e-08.

Discussion

In allopolyploid speciation, two genomes that have experienced long independent evolution are combined. Their genomes were shaped in different ways in response to the extrinsic environmental and intrinsic lifestyle pressures. We focused on As, a species that evolved 12 to 300 KYA from a single hybrid individual formed from an ovule of At and a pollen of Aa. Orthologous genes of At and Aa have average sequence divergence of 5% [43], exhibit differences in tissue-specific expression [10,24], and are located on five versus eight chromosomes. The allotetraploid hybrid initially had low fertility, if one can conclude this from the performance of artificial hybrids in the lab. This fertility can be restored through the complex interplay of genetic and epigenetic processes [22]. Several groups have been fascinated with this rapid but complex process [10,22,24,45,46,53,56-59]. We focus on the subsequent longer-term molecular evolution, by comparing an evolved natural As with an 'unevolved' F1As hybrid.

The summary of F1As unevolved patterns

F1As and its following generations are a model for whole-genome rearrangements and gene expression. Approximately one of ten cDNA amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) bands displayed patterns that were non-additive between F1As and its parental species [16]. One percent of bands were not detected in the parental species altogether [24]. For AFLP fragments observed in the parents, homoeolog silencing was nearly symmetrical: 4% of At versus 5% of Aa. These patterns varied among tissues in a seemingly stochastic way. There was also some variation among accessions. In addition to AFLPs, Wang et al. [53] used spotted 70-mer oligonucleotide arrays to compare gene expression between At, Aa, and F1As. More than 15% of transcripts had different levels between parental species. In F1As, 5% of genes deviated in expression level from the additive mid-parent expectation, with the majority being repressed. Interestingly, 94% of these genes were more strongly expressed in the At parent, with their levels of expression in F1As resembling Aa [56,57]. In conclusion, the levels of gene expression in F1As more frequently resemble those in Aa, although homoeologs seem to have been used symmetrically and sometimes randomly. Aa-specific phenotypes, such as flower morphology, plant stature and long lifespan, are dominant in F1As (likewise, Arabidopsis lyrata phenotypes are dominant in thaliana-lyrata hybrids [56,59]). These results were confirmed and further detailed in very recent investigations [24,45,46].

Evolved As patterns

We found that in As, Aa homoeologs are more frequently retained and more actively transcribed than their At counterparts. We hypothesize that these Aa-favoring biases are not random, but rather represent a signature of an evolutionary process. To explain these patterns, we propose a concept of 'homoeolog competition.' Genes are subject to detrimental mutations at approximately constant rates [47]. Purifying selection removes these mutations with varying efficiencies depending on the gene redundancy, dominance, and other characteristics [6,21,60,61]. As some F1As homoeologs are functionally redundant, they should be progressively lost to mutations and deletions. From the initial pool of homoeologs, natural selection would preferentially maintain those with a higher contribution to fitness. In this sense, homoeologs 'compete'. Despite stoichiometric constraints to maintain stable ratios of dosage among genes [62], there is a well-documented shrinkage of polyploid genomes over time [6,9,12,15,18,21,25,26], as few genes are haploinsufficient [60].

Why would At-originated homoeologs be less valuable? Our first hypothesis is inspired by Hill and Robertson [60]. Selfing organisms, such as At, are less capable of purging mildly deleterious mutations. This is because of severely reduced recombination in comparison to outcrossers, such as Aa [61,63,64]. This may seem paradoxical, as At maintains much less variation than Aa [43], which one might interpret as mutations in Aa. When selfing evolves, segregating mutations are quickly purged, as they exhibit their deleterious nature in autozygous individuals. In the short term, selfers are in fact better off [61]. With time, however, Mullers' ratchet kicks in one slightly deleterious mutation after another, resulting in low standing variation but inferior functionality [47]. Selfing is typical of terminal branches on phylogenetic trees, interpreted as being an evolutionary dead-end [64,65]. Thus, Aa homoeologs may contribute more to the fitness of an F1As, as they originate from an outcrossing species. In the future, we will test this hypothesis by population 'allele-specific' resequencing and applying molecular evolution tests to homoeologs separately.

Our second hypothesis involves historical factors. Suppose the southern-adapted At accession hybridized with the northern-adapted Aa accession, and that the emerging As accession spent most of the 12,000 to 300,000 years in the northern environment [37,39]. Aa-originated homoeologs would be a better fit for the environment, would be more frequently retained, and would evolve to be preferentially used [66]. To test this hypothesis, one must sample As accessions from multiple locations, resequence their genomes and transcriptomes and identify environment-specific molecular evolution since the unique As speciation event. Our model assumes a large standing variation in the genome and transcriptome, which has been well-documented in Tragopogon [35,36]. A more direct, rather than biogeographic-type, evidence might be obtained with Gossypium [14]. This species displays a similar strengthening of parentally skewed expression when natural allotetraploids are compared with F1 allotetraploid controls.

Thirdly, recall that the Aa transcription machinery is preferentially expressed in F1As [53]. Homoeologs pre-adapted to function under Aa transcriptional control will then be selected for, reinforcing this initial pattern. Homoeolog-specific methylation might be at the heart of these processes [45,46]. Indirectly supporting this idea, Aa-like genes exhibited enrichment in the 'gene expression' category (with subprocesses: transcription, translation, RNA processing, and gene silencing by miRNA). Recent reports in Arabidopsis and Brassica allopolyploids indicate a high proportion of nonadditive expression for genes within these categories as well [53,67,68]. Similar results have also been shown in Senecio [69,70].

Resolving incompatibilities in allotetraploid networks

Imagine ancestral genes A1 and A2 that formed a functional dimer in the common ancestor of Aa and At 5 million years ago. These genes evolved into At1 and At2 orthologs in the At lineage, and into Aa1 and Aa2 orthologs in the Aa lineage. Within these lineages, At1 and At2 have been selected for the ability to form a dimer. Likewise, co-evolution has been taking place between Aa1 and Aa2 proteins [48]. In F1As, along with the parental dimers At1-At2 and Aa1-Aa2, there will also be heterologous At1-Aa2 and Aa1-At2 dimers. Are these dimers likely to be functional [48]? Dobzhansky and Muller hypothesized that some would not be [71]. Strongly decreased fitness of At × Aa F1 and F2 seeds, and meiotic disruptions in F1's, attest to the presence of intrinsic incompatibilities contributing to the reproductive isolation of these two species, and some genes involved have been characterized [61,62].

An allotetraploid might walk an evolutionary path to fitness restoration by preferentially co-expressing only one parental set of interacting homoeologs, with mixed networks being less common. The data confirmed our expectation that homoeologous networks in fact evolved towards pure Aa or At profiles. This type of 'D-M homoeolog conflict resolution' should be typical for polyploid ancestors and might potentially contribute to the fractionated genomes we observe today [9,72]. As we now know the identity of networks having evolved to a 'pure' parental type, our strong prediction is that the experimenter-induced heterologous state in these networks shall result in detectable reproductive losses.

Conclusions

When an allotetraploid is formed, the functions of homoeologs are partially redundant, and the genome is set for gene silencing and deletion. Thousands of genes affected by these processes in As were identified with tiling arrays and resequencing. These new computational approaches enable the use of widely available and economical tiling microarrays for the whole-genome analyses of species closely related to the sequenced references. In the As allotetraploid, more At-originated homoeologs are lost and silenced than Aa-originated homoeologs. We hypothesize that these Aa-favoring biases are not random, but rather represent a signature of an evolutionary process. Whenever more than one gene experiences silencing within a network, the homoeolog bias of the first event influences the likewise bias for the subsequent silencing; networks evolve towards their ancestral types. The mosaics of predominantly pure-parental networks in allotetraploids might contribute to phenotypic variability and plasticity, and enable the species to exploit a larger range of environments.

Materials and methods

Plant material, DNA and RNA extractions

Affymetrix GeneChip® Arabidopsis Tiling 1.0R Arrays were hybridized with samples from four different sources. Genomic DNA was obtained from tetraploid At accession Ler [73], tetraploid Aa accession Care-1 [58], allotetraploid As accession Sue-1 [73], and an F1As produced by crossing the tetraploids At and Aa as maternal and paternal parents, respectively [58]. cDNA was prepared from As leaf samples. All genomic DNA and cDNA samples were hybridized in three biological replicates using standard protocols.

Sample Illumina library preparation

RNA purification, cDNA synthesis and Illumina library construction was performed using the protocols of Mortazavi et al. [74] with the following modifications. Total RNA, mRNA, and DNA were quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). mRNA fragmentation was performed using Fragmentation Reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and subsequently cleaned through an RNA cleanup kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Additional DNA and gel purification steps were conducted using Clean and Concentrator kits (Zymo Research). Illumina sequences are available for download at the NCBI Short Read Archive under the accession SRA025958.

Microarray preprocessing and normalization

The Arabidopsis Tiling Microarray is composed of over 3.2 million probe pairs tiled throughout the complete At genome. Probes are tiled at an average of 35 base pairs. Affymetrix CEL files are available for download from the public repository ArrayExpress under the accessions E-MEXP-2968 and E-MEXP-2969. To ensure that arrays within genotypes are comparable to each other, Robust Multiarray Analysis [75,76] was implemented to perform background correction. Intensities for three biological replicates were summarized with quantile normalization [77]. In addition, intensities for the three biological replicates of As and F1As were summarized altogether with quantile normalization. Consistency and density plots may be found in the Additional files. PM probes exhibited some mismatches for the At genotype, as this array is based on a different reference; the arrays exhibited an additional lower hybridization intensity peak. PM probes from conserved exon regions were much more robust.

As expected from interspecific sequence divergence, the number of Aa higher intensity probes decreased, while the number of lower intensity probes increased. Note, however, that 'conservative features' and 'divergent features' peak at similar intensities in both species, making the analyses easier. Similar to At, Aa lower intensity probes were overrepresented in non-coding regions.

Identifying As genomic regions with putative multi-gene alterations

Probe intensities among three biological replicates in As were averaged and paired with the corresponding average among the three F1As replicates. For each gene, a paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test (FDR <0.05) [78] of all probes was used to identify genes with differential hybridization. The significance of individual genes might be misleading, but the pattern for multigene regions is robust. We scanned for windows in which at least 27 (90%) out of 30 genes exhibited unidirectional stronger or unidirectional weaker hybridization in As in comparison with F1As. We also required these differences to be significant at FDR <0.05 for at least 9 (30%) genes. Overlapping windows were collapsed to identify the entirety of these regions.

Multi-genotype array normalization and identification of diagnostic features

Our goal here is to select probe features enabling the comparison of At and Aa signal representation in As DNA and RNA. To enable cross-comparison of DNA and RNA, the analyses have to be made gene-by-gene, with DNA and RNA hybridization signals normalized to the same level with each gene.

First, probes representing conserved signatures between genotypes were identified and used to scale the entire gene. For every probe in a gene, its average intensity among replicates in At was compared to the average intensity in Aa. These ratios formed a unimodal distribution and the peak of this distribution was used as the scaling factor for which to normalize between genotypes for that gene. Mathematically, for probe i in the gene, the average intensity among j biological replicates in both genotypes is defined as:

where aij and tij represent the probe intensities of the jth replicate of the ith probe in Aa and At, respectively. Defining Xi as:

The scaling factor, xmax is defined as:

The value for xmax was estimated using the mlv function in R, which calculates the kernel density and searches for x that maximizes that estimated density function. From hereon, we replace all aij values with rescaled values represented by product(xmax,aij). We disregarded genes whose f(x) failed the Shapiro-Wilks normality test. This normalization method is similar to one recently outlined by Robinson and Oshlack [79], where a scaling parameter is used to normalize between two samples.

Second, we identified single feature polymorphisms or DFs between At and Aa using a Welch t-test of log2-transformed values, followed by controlling FDR to be smaller than 0.05. These approaches enabled us to analyze homoeolog-specific retention in 24,344 out of approximately 39,000 At genes.

Analysis of DFs in DNA samples from As

If an As gene retained both parental homoeologs, we should observe an equal mix of At and Aa signals. A linear model was used to determine whether As has probe intensities within a gene contributed by i) both parents (mixed), ii) parental At only (At-like), or iii) parental Aa only (Aa-like). For a gene with n DFs, the vector of intensities, S = [S1, S2,..., Sn], may be contributed by corresponding Aa- and At-specific signals, such that S = α1•A + β1•T and the contribution of Aa, α1, can be estimated using a simple linear regression. Specifically:

where i = 1,2,..,n, j = 1,2,3 for the three biological replicates, and Ai and Ti are the mean intensities in Aa and At, respectively. εij are error terms that are independent random variables from a normal distribution with a mean 0 and variance σ2. The strength of our experimental design is in F1As, in which a null model holds true for genomic DNA. For F1As, this expectation is:

To detect deviations from the null, we tested whether α1 is significantly different from α2. Under the null hypothesis that α1 = α2, and assuming α + β = 1:

follows an F distribution with 1 and 6n - 1 degrees of freedom. This assumption of α + β = 1 can be made since the contributions of Aa and At are weighted. The bias was labeled as Aa-like if α1 > α2 and as At-like if α1 < α2. To account for multiple testing issues arising from thousands of genes tested, Benjamini-Hochberg's FDR was employed to adjust the significance level at 0.05 [78].

As with all linear regression models, we assume that the error terms follow a normal distribution. We investigated this by applying a Shapiro-Wilks test on each gene to ensure that they were normal. We removed over 7,000 genes that failed these tests. We found little discrepancy for the results of the analyses when α1 was defined as the At contribution. We also determined significance by performing a permutation test for each gene and found little discrepancy with the F distribution shown above.

Analysis of DFs in As transcripts

Since we are estimating the relative contribution of Aa rather than the absolute, the expression level of every gene in the As transcriptome was normalized to identical hybridization levels with its corresponding genomic DNA. This was done using probes representing conserved signatures, identified as previously described. We then analyzed the homoeolog-specific expression with the same linear model approach as above, using DFs identified between RNA and DNA, and α found in As DNA as the null reference point. When these intensities of DFs are biased in one direction, we can determine homoeolog-specific expression. Furthermore, for each gene, α was estimated by regressing over all DFs in the set, minimizing spurious effects of individual probes. Forty-nine percent of genes were expressed. Distributions of intensities for conserved features in As DNA and RNA prior to and after gene-wise normalization are shown in the Additional files. The homoeolog-specific expression was assayed in 18,876 genes.

Illumina data analysis

Pair-ended 72-base Illumina reads were aligned and mapped allowing up to 10 mismatches using bwa [80] to 102 Aa transcript sequences and their orthologous At sequences. A pairwise global alignment identified SNPs and short insertion/deletion variants between orthologous Aa and At gene pairs. Reads that mapped to either of the two orthologs were scanned for these variants to ensure that they were clustered with the appropriate ortholog (Figure 6). The number of reads mapped to each ortholog was normalized to FPK (fragments per kilobase of exon) to account for slightly variable sequence length between orthologs. This analysis and its results are summarized in Figures 6 and 7, and in Additional file 5.

Variation within Aa and At

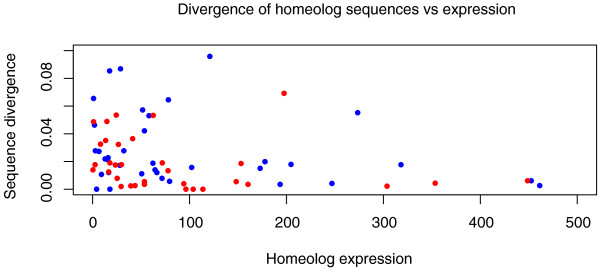

Note that although extant accessions of Aa, At, and F1As were used, As was formed 12 to 300 KYA, perhaps from different accessions. DFs and Illumina resequencing may potentially result in misleading conclusions. Nevertheless, 5 million years of sequence divergence between Aa and At compares favorably with the smaller amount of standing sequence variation and with the unaccounted extra divergence since As formation. From the above resequencing data, we estimated the divergence of the Aa homoeolog within As from the homologous gene in Aa. Likewise, we estimated the divergence of the At homoeolog within As from the homologous gene in At. Consistent with high sequence variation in Aa [43], the divergence from parental homologs is larger in Aa, as sequence variation in natural At is very limited [42]. This would result in fewer Aa-like calls, and lower biases detected in this manuscript. Note that, as expected from [66], stronger expressed genes appear more conserved and exhibit lesser Aa and At divergences (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Divergence of At and Aa homoeologs in As in comparison with At and Aa references (Y-axis) compared to homoeolog-specific expression (X-axis).

Abbreviations

Aa: Arabidopsis arenosa; AFLP: amplified fragment length polymorphism; As: Arabidopsis suecica; At: Arabidopsis thaliana; DF: diagnostic feature; F1As: F1 artificial allotetraploid; FDR: false discovery rate; KYA: thousand years ago; SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PLC performed the computational and statistical analysis of the data, carried out the molecular resequencing, and drafted the manuscript. BPD performed sequence extraction and microarray experiments, and drafted the manuscript. MM performed sequence extraction and microarray experiments. LC participated in the design of the study. SVN conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Differential hybridization between As and F1As. Excel table showing 6,790 genes with differential hybridization between As and F1As (Wilcoxon ranked sum test, FDR <0.05).

Differentially hybridized clusters between As and F1As. Excel table showing 1,643 genes found within differentially hybridized clusters between As and F1As. Clusters contain at least 30 genes with a strong unidirectional bias, where at least 27 genes have the same bias, and significant for at least 9 genes.

Outline of genes included and analyzed. Excel table outlining the number of genes discarded and included at each step in the analysis.

Homoeolog-specific retention in As DNA. Excel table showing 938 genes with homoeolog-specific retention in As DNA.

Comparison of homoeolog-specific expression estimated from At tiling microarray and Illumina resequencing. Excel table showing comparison of expression for 102 genes using both At tiling microarrays and Illumina resequencing.

Summary of probe hybridization intensities between At, Aa, As, and F1As. Probe hybridization intensities are shown for various regions throughout the genome (Figures S1 to S12). Density plots are shown for probe hybridization of DNA for PM and MM probes (Figures S13 to S16). A density plot is shown for conserved probes in As DNA and As RNA before and after gene-level normalization.

Contributor Information

Peter L Chang, Email: peter.chang@usc.edu.

Brian P Dilkes, Email: bdilkes@purdue.edu.

Michelle McMahon, Email: mcmahonm@cals.arizona.edu.

Luca Comai, Email: lcomai@ucdavis.edu.

Sergey V Nuzhdin, Email: snuzhdin@usc.edu.

Acknowledgements

BPD and LC were supported by grant DBI0733857 from NSF Plant Genome Research Program. The authors are grateful to Joseph Fass, Meric Lieberman and Victor Missirian at the UC Genome Center for providing of A. arenosa sequences. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions during the review of the manuscript.

References

- Ehrendorfer F. Polyploidy and distribution. Basic Life Sci. 1979;13:45–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-3069-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant V. Plant Speciation. New York, USA: Columbia University; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn TC, Pires JC, Birchler JA, Auger DL, Chen ZJ, Lee HS, Comai L, Madlung A, Doerge RW, Colot V, Martienssen RA. Understanding mechanisms of novel gene expression in polyploids. Trends Genet. 2003;19:141–147. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson J. Stomatal size in fossil plants: evidence for polyploidy in majority of angiosperms. Science. 1994;264:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5157.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood TE, Takebayashi N, Barker MS, Mayrose I, Greenspoon PB, Rieseberg LH. The frequency of polyploid speciation in vascular plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13875–13879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811575106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP, Whitton J. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:401–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzhdin SV, Wayne ML, Harmon KL, McIntyre LM. Common pattern of evolution of gene expression level and protein sequence in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1308–1317. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranz JM, Castillo-Davis CI, Meiklejohn CD, Hartl DL. Sex-dependent gene expression and evolution of the Drosophila transcriptome. Science. 2003;300:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.1085881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS, Soltis DE. The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:561–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Percifield R, Wendel JF. Organ-specific silencing of duplicated genes in a newly synthesized cotton allotetraploid. Genetics. 2004;168:2217–2226. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Wendel JF. Novel patterns of gene expression in polyploid plants. Trends Genet. 2005;21:539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Ni Z. Mechanisms of genomic rearrangements and gene expression changes in plant polyploids. Bioessays. 2006;28:240–252. doi: 10.1002/bies.20374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M, Liu B, Segal G, Abbo S, Levy AA, Vega JM. Rapid elimination of low-copy DNA sequences in polyploid wheat: a possible mechanism for differentiation of homoeologous chromosomes. Genetics. 1997;147:1381–1387. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel L, Udall JA, Nettleton D, Wendel JF. Duplicate gene expression in allopolyploid Gossypium reveals two temporally distinct phases of expression evolution. BMC Biol. 2008;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashkush K, Feldman M, Levy AA. Gene loss, silencing and activation in a newly synthesized wheat allotetraploid. Genetics. 2002;160:1651–1659. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Chen ZJ. Protein-coding genes are epigenetically regulated in Arabidopsis polyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6753–6758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121064698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Brubaker CL, Mergeai G, Cronn RC, Wendel JF. Polyploid formation in cotton is not accompanied by rapid genomic changes. Genome. 2001;44:321–330. doi: 10.1139/gen-44-3-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Vega JM, Feldman M. Rapid genomic changes in newly synthesized amphiploids of Triticum and Aegilops. II. Changes in low-copy coding DNA sequences. Genome. 1998;41:535–542. doi: 10.1139/gen-41-4-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madlung A, Masuelli RW, Watson B, Reynolds SH, Davison J, Comai L. Remodeling of DNA methylation and phenotypic and transcriptional changes in synthetic Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:733–746. doi: 10.1104/pp.003095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke MA, Scheid OM, Matzke AJM. Rapid structural and epigenetic changes in polyploid and aneuploid genomes. Bioessays. 1999;21:761–767. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199909)21:9<761::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP. The evolutionary consequences of polyploidy. Cell. 2007;131:452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes O, Ng P, Silva M, Lewis MS, Madlung A, Comai L, Viegas W, Pikaard CS. Chromosomal locus rearrangements are a rapid response to formation of the allotetraploid Arabidopsis suecica genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18240–18245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407258102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Lu P, Tang K, Oshlack A. Rapid genome change in synthetic polyploids of Brassica and its implications for polyploid evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7719–7723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Tian L, Madlung A, Lee HS, Chen M, Lee JJ, Watson B, Kagochi T, Comai L, Chen ZJ. Stochastic and epigenetic changes of gene expression in Arabidopsis polyploids. Genetics. 2004;167:1961–1973. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF. Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:225–249. doi: 10.1023/A:1006392424384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Wendel JF. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KL, Cronn RC, Percifield R, Wendel JF. Genes duplicated by polyploidy show unequal contributions to the transcriptome and organ-specific reciprocal silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4649–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630618100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottley A, Koebner RM. Variation for homoeologous gene silencing in hexaploid wheat. Plant J. 2008;56:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottley A, Xia GM, Koebner RM. Homoeologous gene silencing in hexaploid wheat. Plant J. 2006;47:897–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary B, Flagel L, Stupar RM, Udall JA, Verma N, Springer NM, Wendel JF. Reciprocal silencing, transcriptional bias and functional divergence of homeologs in polyploid cotton (gossypium). Genetics. 2009;182:503–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel LE, Wendel JF. Evolutionary rate variation, genomic dominance and duplicate gene expression evolution during allotetraploid cotton speciation. New Phytol. 2009;186:184–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp RA, Udall JA, Wendel JF. Genomic expression dominance in allopolyploids. BMC Biol. 2009;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggs RJ, Chamala S, Wu W, Gao L, May GD, Schnable PS, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Barbazuk WB. Characterization of duplicate gene evolution in the recent natural allopolyploid Tragopogon miscellus by next-generation sequencing and Sequenom iPLEX MassARRAY genotyping. Mol Ecol. 2010;19(Suppl 1):132–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggs RJ, Doust AN, Tate JA, Koh J, Soltis K, Feltus FA, Paterson AH, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Gene loss and silencing in Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae): comparison of natural and synthetic allotetraploids. Heredity. 2009;103:73–81. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KY, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Tate J, Matyasek R, Srubarova H, Kovarik A, Pires JC, Xiong Z, Leitch AR. Rapid chromosome evolution in recently formed polyploids in Tragopogon (Asteraceae). PLoS One. 2008;3:e3353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate JA, Joshi P, Soltis KA, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. On the road to diploidization? Homoeolog loss in independently formed populations of the allopolyploid Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae). BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Säll T, Lind-Halldén C, Jakobsson M, Halldén C. Mode of reproduction in Arabidopsis suecica. Hereditas. 2005;141:313–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2004.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulten E. Atlas of the Distribution of Vascular Plants in Northwestern Europe. Stockholm: Generalstabens Litografiska Anstalts Forlag; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson M, Hagenblad J, Tavaré S, Säll T, Halldén C, Lind-Halldén C, Nordborg M. A unique recent origin of the allotetraploid species Arabidopsis suecica: evidence from nuclear DNA markers. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1217–1231. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msk006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummenhoff K, Hurka H. Allopolyploid origin of Arabidopsis suecica (Fries) Norrlin: Evidence from chloroplast and nuclear genome markers. Botanica Acta. 1995;108:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Säll T, Jakobsson M, Lind-Halldén C, Halldén C. Chloroplast DNA indicates a single origin of the allotetraploid Arabidopsis suecica. J Evol Biol. 2003;16:1019–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shehbaz IA, O'Kane SL. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Arabidopsis (Brassicaceae). The Arabidopsis Book. 2002;6:1–22. doi: 10.1199/tab.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch MA, Matschinger M. Evolution and genetic differentiation among relatives of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6272–6277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701338104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch MA, Haubold B, Mitchell-Olds T. Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae). Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1483–1498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Ha M, Lackey E, Wang J, Chen ZJ. RNAi of met1 reduces DNA methylation and induces genome-specific changes in gene expression and centromeric small RNA accumulation in Arabidopsis allopolyploids. Genetics. 2008;178:1845–1858. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.086272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha M, Lu J, Tian L, Ramachandran V, Kasschau KD, Chapman EJ, Carrington JC, Chen X, Wang XJ, Chen ZJ. Small RNAs serve as a genetic buffer against genomic shock in Arabidopsis interspecific hybrids and allopolyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17835–17840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907003106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley PD, Otto SP. Interference among deleterious mutations favours sex and recombination in finite populations. Nature. 2006;443:89–92. doi: 10.1038/nature05049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA, Orr HA. The evolutionary genetics of speciation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:287–305. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graze RM, McIntyre LM, Main BJ, Wayne ML, Nuzhdin SV. Regulatory divergence in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans, a genomewide analysis of allele-specific expression. Genetics. 2009;183:547–561. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.105957. 541SI-521SI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz JO, Hazen SP, Michael TP, Morris GP, Baxter IR, Hu TT, Chen H, Werner JD, Nordborg M, Salt DE. Genome-wide patterns of single-feature polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12057–12062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705323104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baross A, Delaney AD, Li HI, Nayar T, Flibotte S, Qian H, Chan SY, Asano J, Ally A, Cao M, Birch P, Brown-John M, Fernandes N, Go A, Kennedy G, Langlois S, Eydoux P, Friedman JM, Marra MA. Assessment of algorithms for high throughput detection of genomic copy number variation in oligonucleotide microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:368. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Tian L, Lee HS, Wei NE, Jiang H, Watson B, Madlung A, Osborn TC, Doerge RW, Comai L, Chen ZJ. Genomewide nonadditive gene regulation in Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Genetics. 2006;172:507–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey JG, Nuzhdin SV, Ye F, Jones CD. Coordinated evolution of co-expressed gene clusters in the Drosophila transcriptome. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Gong Q, Bohnert HJ. An Arabidopsis gene network based on the graphical Gaussian model. Genome Res. 2007;17:1614–1625. doi: 10.1101/gr.6911207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J, Jean M, Belzile F. The allotetraploid Arabidopsis thaliana-Arabidopsis lyrata subsp. petraea as an alternative model system for the study of polyploidy in plants. Mol Genet Genomics. 2009;281:421–435. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Comai L, Pikaard CS. Gene dosage and stochastic effects determine the severity and direction of uniparental ribosomal RNA gene silencing (nucleolar dominance) in Arabidopsis allopolyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14891–14896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L, Tyagi AP, Winter K, Holmes-Davis R, Reynolds SH, Stevens Y, Byers B. Phenotypic instability and rapid gene silencing in newly formed Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1551–1568. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah ME, Yogeeswaran K, Snyder S, Nasrallah JB. Arabidopsis species hybrids in the study of species differences and evolution of amphiploidy in plants. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1605–1614. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JH. Junk ain't what junk does: neutral alleles in a selected context. Gene. 1997;205:291–299. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00470-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SI, Lauga B, Charlesworth D. Rates and patterns of molecular evolution in inbred and outbred Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:1407–1420. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Veitia RA. The gene balance hypothesis: implications for gene regulation, quantitative traits and evolution. New Phytol. 2009;186:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller R, Smith JM. Does Muller's ratchet work with selfing? Genet Res. 2009;32:289–293. doi: 10.1017/S0016672300018784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi N, Morrell PL. Is self-fertilization an evolutionary dead end? Revisiting an old hypothesis with genetic theories and a macroevolutionary approach. Am J Bot. 2001;88:1143–1150. doi: 10.2307/3558325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins GL. Self fertilization and population variability in the higher plants. Am Nat. 1957;91:337–354. doi: 10.1086/281999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Force A. The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics. 2000;154:459–473. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta RT, Yoo SY, Pires JC, Doerge RW, Chen ZJ, Oshlack A. Analysis of gene expression in resynthesized Brassica napus allopolyploids using Arabidopsis 70 mer oligo microarrays. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha M, Kim ED, Chen ZJ. Duplicate genes increase expression diversity in closely related species and allopolyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2295–2300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807350106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty MJ, Barker GL, Wilson ID, Abbott RJ, Edwards KJ, Hiscock SJ. Transcriptome shock after interspecific hybridization in Senecio is ameliorated by genome duplication. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1652–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty MJ, Jones JM, Wilson ID, Barker GL, Coghill JA, Sanchez-Baracaldo P, Liu G, Buggs RJA, Abbott RJ, Edwards KJ. Development of anonymous cDNA microarrays to study changes to the Senecio floral transcriptome during hybrid speciation. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2493–2510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2005.02608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True JR, Haag ES. Developmental system drift and flexibility in evolutionary trajectories. Evol Dev. 2001;3:109–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003002109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BC, Pedersen B, Freeling M. Following tetraploidy in an Arabidopsis ancestor, genes were removed preferentially from one homeolog leaving clusters enriched in dose-sensitive genes. Genome Res. 2006;16:934–946. doi: 10.1101/gr.4708406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilkes BP, Spielman M, Weizbauer R, Watson B, Burkart-Waco D, Scott RJ, Comai L. The maternally expressed WRKY transcription factor TTG2 controls lethality in interploidy crosses of Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. http://www.jstor.org/pss/2346101 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows - Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Differential hybridization between As and F1As. Excel table showing 6,790 genes with differential hybridization between As and F1As (Wilcoxon ranked sum test, FDR <0.05).

Differentially hybridized clusters between As and F1As. Excel table showing 1,643 genes found within differentially hybridized clusters between As and F1As. Clusters contain at least 30 genes with a strong unidirectional bias, where at least 27 genes have the same bias, and significant for at least 9 genes.

Outline of genes included and analyzed. Excel table outlining the number of genes discarded and included at each step in the analysis.

Homoeolog-specific retention in As DNA. Excel table showing 938 genes with homoeolog-specific retention in As DNA.

Comparison of homoeolog-specific expression estimated from At tiling microarray and Illumina resequencing. Excel table showing comparison of expression for 102 genes using both At tiling microarrays and Illumina resequencing.

Summary of probe hybridization intensities between At, Aa, As, and F1As. Probe hybridization intensities are shown for various regions throughout the genome (Figures S1 to S12). Density plots are shown for probe hybridization of DNA for PM and MM probes (Figures S13 to S16). A density plot is shown for conserved probes in As DNA and As RNA before and after gene-level normalization.