Abstract

Obesity is increasing in resource-poor nations at an alarming rate. Obesity is a risk factor for noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and high-risk pregnancy. The combination of obesity and its concomitant diseases affects more women than men. Obesity places a large burden on an already thinly stretched health system that creates a public health challenge. Given faster population growth, increased urbanization, and lifestyle changes, an epidemic of obesity is expected in resource-poor nations within the next decade. Diet, exercise, medication, and weight-loss surgery are methods of weight reduction, but cultural and public health considerations must be assessed when implementing these various methods of weight loss.

Key words: Obesity, Diet, Exercise, Bariatric surgery

When one thinks about populations living in resource-poor nations, images of emaciated children with kwashiorkor or marasmus immediately come to mind. For decades, international organizations have focused on malnutrition and its ramifications. Indeed, this remains true in developing nations that suffer from protein-energy malnutrition, vitamin A and iodine deficiencies, and iron-deficiency anemia. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) is concerned that there is an emerging pandemic of obesity in resource-poor nations. The diseases that develop as a consequence of obesity—diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke—will undoubtedly overwhelm health systems.

Background

Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (Table 1). In the West, obesity is seen as a chronic disease contributing to excessive morbidity and mortality and accounting for an estimated 2.5 million deaths per year. In 2005, WHO estimated that approximately 1.6 billion adults were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and 400 million adults were obese.1 WHO projects that by 2015, 2.3 billion adults will be overweight and 700 million adults will be obese, with a rapidly growing number in developing nations.1 New cases of diabetes alone are predicted to reach over 200 million in the next 2 decades.2 Over 80% of cardiovascular disease occurs in resource-poor nations. Obesity is a growing problem throughout the world.

Table 1.

| BMI | Classification |

| < 18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal weight |

| 25.0–29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0–34.9 | Class I obesity |

| 35.0–39.9 | Class II obesity |

| ≥ 40.0 | Class III obesity |

Body mass index (BMI) is calculated by dividing the subject’s mass by the square of his or her height: BMI = kg/m2.

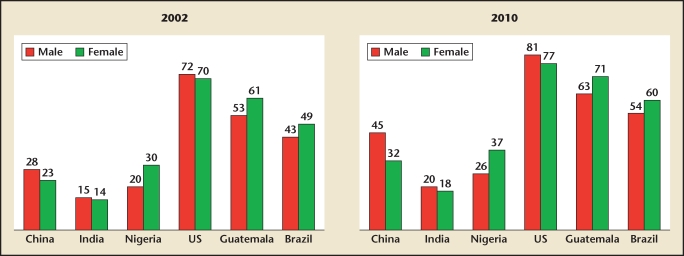

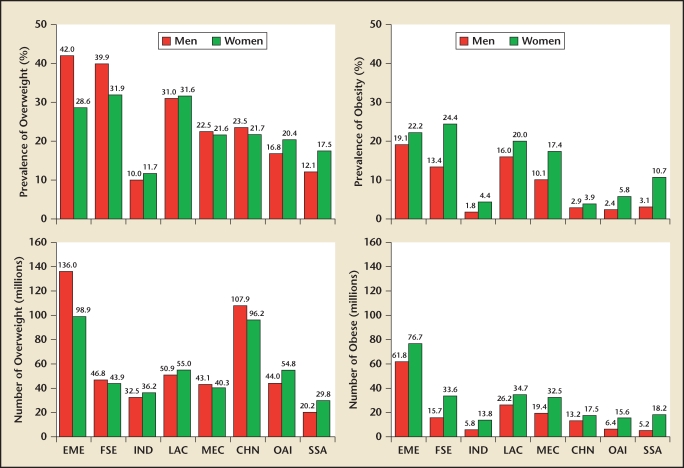

The prevalence of overweight and obese adults is higher in economically developed nations, but the prevalence is surprisingly high in countries like South Africa, Libya, and Brazil.3 The majority of obesity in developing nations is seen in countries whose per capita gross domestic product is under $5000, such as Guatemala and Nigeria (Figure 1). An increase in obesity in women was found in the Middle East/North Africa and Latin America/Caribbean regions (Figure 2). When comparisons throughout the world were made between men and women, the prevalence of obesity was higher among women (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Percentage of overweight population (selected countries) in 2002 and 2010 (projected). Source: World Health Organization Global InfoBase Online.

Figure 2.

Nutrition experts are concerned about the growing problem of obesity in the developing world. CEE/CIA, Central Eastern Europe/Commonwealth of Independent States. Reprinted with permission from Martorell R et al, Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000:54;247–252.

Figure 3.

Age-standardized prevalence (upper) and absolute number (lower) of overweight and obesity in adults age 20 years and older by world region and sex in 2005. CHN, China; EME, established market economies; FSE, former socialist economies; IND, India; LAC, Latin America and the Caribbean; MEC, middle eastern crescent; OAI, other Asia and islands; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa. Reprinted with permission from Kelly T et al.3

Changes in Lifestyle and Diet

In the past, resource-poor nations sustained diets that, at worst, lacked enough caloric intake and, at best, consisted of fresh, farm-grown crops and fish obtained from seas or rivers. Over time, diets have shifted from traditional foods to a Western diet that includes processed foods, sugar, and highly saturated fats.4 This change in diet, along with reduced manual labor and increased motorized transportation, has enabled obesity to emerge. Even in sub- Saharan Africa, households may consist of overweight adults and underweight children, all suffering from poor nutrition.5

Cultural Perspective

Other forces promoting an increase of obesity in developing nations is that obesity is not stigmatized. An overweight woman in certain cultures is desirable. Obesity is associated with beauty, higher socioeconomic status, power, and better health. For example, in Nigeria, women are almost 3 times more likely to be obese than men.6 In the Gambia, studies on women’s body image portrayed high satisfaction with obesity. In South Africa, thinness is associated with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS); being overweight or obese is considered a sign of HIV-negative status.2 Unlike developed nations in which women’s obesity is inversely related to socioeconomic status, women’s obesity in most developing nations is seen in urban areas among higher socioeconomic brackets.7

Impact on Women’s Health and the Health System

Obesity and its associated diseases are costly to women, their lives, and the health care system. Given that obesity is a risk factor for diabetes, the rate of diabetes in developing nations has grown significantly. Indeed, 4 out of every 5 women with diabetes are living in developing nations.8 The International Federation of Diabetes projects that more women than men will die of diabetes and diabetes-related complications, such as nephropathy and coronary heart disease.8 In addition, pregnant, obese women face major health risks including gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and increased morbidity and mortality during cesarean deliveries. Health systems in resource-poor nations are not equipped to treat high-risk, pregnant patients. Many nations’ health budgets are consumed by infectious and acute diseases and do not address noncommunicable diseases. According to WHO, even countries with larger budgets, such as India and China, will lose $900 billion of national income between 2005 and 2015 to diabetes and cardiovascular disease.8

Treatment

Diet and Exercise

Diet and exercise are the first line of treatment that is routinely recommended to obese women. For example, diet modification with reduction in caloric and saturated fat intake or high protein is recommended. Individual and group exercise programs are encouraged. However, in general, staying motivated for life is nearly impossible for those who are morbidly obese. Given the cultural forces discussed earlier, encouraging women to exercise and lose weight can be challenging. Women who have witnessed a death from diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or stroke may be motivated, but changing social norms present an even greater public health dilemma. Governments and ministries of health must be supportive. In conservative nations, women-only gyms have grown in popularity, allowing for privacy and solidarity among women.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Antiobesity drugs attempt to alter the digestive and psychologic process of the human body. There are medications that suppress the appetite, decrease absorption in the gastrointestinal system, block fat breakdown, or increase body metabolism. Most medications are by prescription only. Nonprescription therapies include fiber supplements and guar gum. Although these medications have been used in the United States, there are few data on whether these medications are used or even affordable in resource-poor nations.

Gastric Bypass

The National Institutes of Health published a consensus statement determining that, in patients with morbid obesity requiring long-term weight loss, the most successful intervention is bariatric surgery.9 Bariatric surgery (also referred to as weight-loss surgery) is recommended to patients with a BMI > 40 who have failed diets, exercise, and pharmacological treatments. Studies have determined that patients who undergo bariatric surgery experience significant weight loss, and a decrease in obesity-induced diseases (diabetes, cardiovascular risks, cancer) resulting in improvements in their long-term survival.10,11 Bariatric surgery is increasing worldwide, with over 225,000 surgeries completed in the United States alone in 2008. Bariatric surgery, specifically the Roux-en-Y, is not without risks. In the Roux-en-Y procedure, a portion of the stomach is made smaller and the top portion is connected to the jejunum, thus bypassing the remainder of the stomach and duodenum. Postoperative complications include bleeding, infection, and leakage of stomach contents into the abdominal cavity, resulting in peritonitis, pulmonary emboli, and death. In the United States, mortality rates are stated as less than 1%.12 Long-term complications include ulcers, gallstones, hernias, nutritional deficiencies, and osteoporosis.13

Gastric bypass surgery is performed in low- and middle-income nations; weight loss surgery is a growing specialty among surgeons in developing nations. The majority of their patients arrive as medical tourists. Medical tourism is a growing trend in which individuals travel to another country to obtain medical care or surgery at a reduced cost. When “gastric bypass” + “medical tourism” is entered into a computer search engine, destinations such as Thailand, Mexico, India, Costa Rica, and Jordan appear. Web sites describe the surgery but do not always display the risks and complications of the procedure, and are clearly targeting individuals who are self-paying. In the next decade, when obesity becomes a serious epidemic in the developing world, it will be interesting to see whether gastric bypass will be a possibility for those without financial means living in developing nations.

Conclusions

WHO has placed obesity at the top of the list of chronic diseases. Governments, ministries of health, and nongovernment organizations must begin to focus on this issue before the potential epidemic reaches its projection. Populations that have yet to be urbanized must be encouraged to maintain a healthy diet and exercise. Discouraging the consumption of processed, high-fat foods and sugar is vital. Governments and the private sector should make responsible decisions when investing in their nation. Allowing unhealthy fastfood restaurants to enter and expand will target the most vulnerable: those living in poverty. By promoting health and preventing obesity, the growing rate of noncommunicable and chronic diseases can ultimately be reduced.

Main Points.

The majority of obesity in developing nations is seen in countries whose per capita gross domestic product is under $5000. An increase in obesity in women is found in the Middle East/North Africa and Latin America/Caribbean regions.

Diets have shifted from traditional foods to a Western diet that includes processed foods, sugar, and highly saturated fats. This change in diet, along with reduced manual labor and increased motorized transportation, has enabled obesity to emerge.

In sub-Saharan Africa, households may consist of overweight adults and underweight children, all suffering from poor nutrition.

Pregnant, obese women face major health risks including gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and increased morbidity and mortality during cesarean deliveries. Health systems in resource-poor nations are not equipped to treat high-risk, pregnant patients.

By promoting health and preventing obesity, the growing rate of noncommunicable and chronic diseases can ultimately be reduced.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, authors. Obesity and Overweight. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. (Fact sheet no. 311). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prentice A. The emerging epidemic of obesity in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:93–99. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, et al. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obesity. 2008;32:1431–1437. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popkin BM, Lu B, Zhai F. Understanding the nutrition transition: measuring rapid dietary changes in transition countries. Publ Health Nutr. 2002;5:947–953. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caballero B. A nutrition paradox-underweight and obesity in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1514–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olatunbosun ST, Kaufman JS, Bella AF. Prevalence of obesity and overweight in urban adult Nigerians [published online ahead of print September 6, 2010] Obes Rev. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00801.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montiero CA, Conde WL, Lu B, Popkin BM. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int J Obes. 2004;28:1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Diabetes Federation, authors. [Accessed October 28, 2010];Morbidity and mortality. IDF Diabetes Atlas Web site. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/content/diabetesmortality. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gastrointestinal Surgery for Severe Obesity, authors. NIH Consens Statement Online. 1991 Mar 25–27;9(1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;14:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith C, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753–761. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:547–559. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, authors. [Accessed October 28, 2010];Bariatric surgery for severe obesity. Weight-control Information Network Web site. http://www.win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/gastric.htm. [Google Scholar]