Abstract

UV resonance Raman spectroscopy (UVRR) is a powerful method that has the requisite selectivity and sensitivity to incisively monitor biomolecular structure and dynamics in solution. In this perspective, we highlight applications of UVRR for studying peptide and protein structure and the dynamics of protein and peptide folding. UVRR spectral monitors of protein secondary structure, such as the Amide III3 band and the Cα-H band frequencies and intensities can be used to determine Ramachandran Ψ angle distributions for peptide bonds. These incisive, quantitative glimpses into conformation can be combined with kinetic T-jump methodologies to monitor the dynamics of biomolecular conformational transitions. The resulting UVRR structural insight is impressive in that it allows differentiation of, for example, different α-helix-like states that enable differentiating π- and 310- states from pure α-helices. These approaches can be used to determine the Gibbs free energy landscape of individual peptide bonds along the most important protein (un)folding coordinate. Future work will find spectral monitors that probe peptide bond activation barriers that control protein (un)folding mechanisms. In addition, UVRR studies of sidechain vibrations will probe the role of side chains in determining protein secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures.

Keywords: Protein folding, melting dynamics, T-jump, UV resonance Raman spectroscopy, UVRR transient spectra, protein (un)folding kinetics

The protein folding problem

An understanding of the mechanism(s) of protein folding, whereby the ribosome synthesized biopolymer folds into its native protein is arguably one of the most important unsolved problem in biology.1–7 The primary sequence of many or most proteins encodes both the native structure as well as the folding mechanism pathway to the native structure.8–10 An understanding of the encoded protein folding “rules” would dramatically speed insight into protein structure and function.

A number of mechanisms have been proposed that differ in the order of folding events. The framework model11 and the diffusion-collision model12 propose that the initial step in folding involves formation of native-like secondary structural units, while the hydrophobic collapse model and the nucleation-condensation model13 suggest that hydrophobic or nucleating domains fold first, and that these structures drive the subsequent formation of secondary structure. Recent energy landscape models14 propose the occurrence of funnel-shaped folding energy landscapes, where the native state is accessed via a strategically sloped energy landscape that funnel myriads of partially folded conformations towards the native folded state.15

Techniques for studying protein folding

Numerous experimental techniques are being applied to study protein folding. In addition, various theoretical approaches are also being utilized with empirically developed parameters to try to get insight into the folding mechanisms.16 UV-Visible absorption spectroscopy was the first technique used to monitor the UV absorption of the peptide backbone. This method was able to detect protein backbone conformational changes because of the hypoand hyperchromic interactions that, for example, result from peptide bond excitonic interactions in the α-helix conformation.17,18 The development of circular dichroism spectroscopy enabled more direct monitoring of protein secondary structural content, especially the occurrence of α-helical conformations.19

X-ray Crystallography is the gold standard technique for determining static protein structures (from protein crystals), and much of the insight into protein science has resulted from the many incisive stationary x-ray structures. However, these static x-ray structures do not give the dynamic structural information essential to determine enzymatic mechanisms, for example.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) is an extraordinarily powerful tool for studying protein folding.20 The technique is also capable of elucidating detailed aspects of the structure and dynamics of large proteins. However, the atomic distances and dihedral angles measured by this technique are generally time averages.21

Laser spectroscopy techniques enable highly incisive structural investigations that can be utilized to study dynamics in the fsec to static time scales. IR and Raman vibrational spectroscopies can monitor small changes in protein structure resulting from tiny ~0.001 nm bond length changes. Unfortunately, the use of IR absorption spectroscopy is challenging for biological samples, because it is generally limited to D2O solution samples due to the overwhelming IR absorption of H2O.22

Raman spectroscopy monitors the vibrations of gas, liquid and solid samples.23–25 H2O is a relatively weak Raman scatterer. This enables Raman studies of biological molecules in H2O. Raman spectroscopy is an inelastic light scattering phenomenon where the incident electromagnetic field interacts with a molecule such that there is an exchange of a quantum of vibrational energy between the two, resulting in a vibrational frequency difference between the incident and scattered light.26–35 In normal, or off-resonance Raman scattering the incident photon at a frequency outside of any electronic absorption band is inelastically scattered, leaving the molecule in an excited vibrational level of the electronic ground state (for Stokes scattering). A similar vibrational transition occurs for resonance Raman scattering, where excitation occurs at a frequency within an electronic absorption band. In this case the vibrational modes observed are particular vibrations whose motions couple to the driven electronic motion occurring in the electronic transition. The vibrational modes enhanced are those localized in the chromophoric segments.

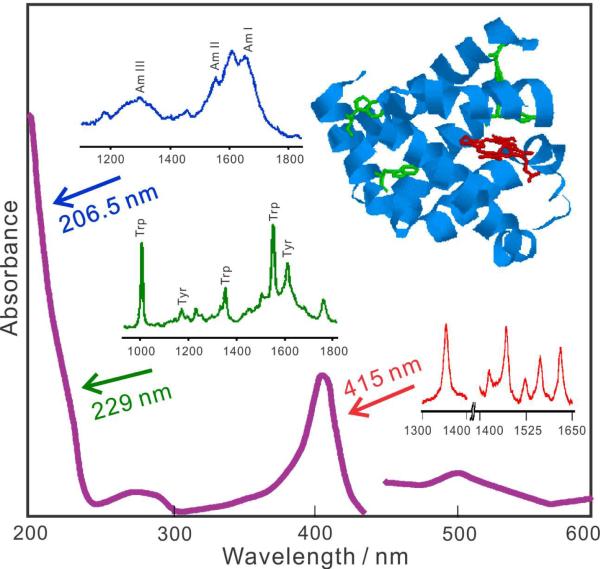

The additional resonance Raman enhancement can be an additional 106–108-fold. This results in a crucial ultra-high resonance Raman selectivity and sensitivity that makes it a very powerful technique for studying macromolecules; instead of all the sample vibrations contributing with comparable intensities, only a small subset of resonance Raman enhanced vibrations localized around the chromophoric group dominate the spectra. By judiciously tuning the excitation wavelength, we can selectively enhance particular vibrations in particular regions of the macromolecule.36,37 Fig. 1 demonstrates the UVRR selectivity available, for example, for studying the protein myoglobin (Mb).38,39 The visible wavelength absorption bands of Mb result from the in-plane π→π* electronic transitions of its heme group. UVRR excitation of Mb at 415 nm in the strong heme Soret absorption band, results in an intense UVRR spectra which contains only the in-plane heme ring vibrations.40 In contrast, excitation at 229 nm within the absorption bands of the tyr and trp aromatic side chains shows UVRR spectra completely dominated by tyr and trp aromatic ring sidechain vibrations.39,41 Deeper UV excitation at 206.5 nm, within the π→π* transitions of the amide peptide bonds, shows UVRR spectra dominated by the peptide bond amide vibrations.39

Figure 1.

Selectivity of resonance Raman spectral measurements of myoglobin showing the protein absorption spectrum and the different resonance Raman spectra obtained with different excitation wavelengths.

Thus, tuning the UVRR excitation wavelengths, allows the probing of different chromophoric segments of a macromolecule. Another advantage of deep UV Raman measurements is that there is no interference from molecular relaxed fluorescence.42 In addition, UVRR can also be used in pump-probe measurements to give kinetic information on fast biological processes.43

UVRR Instrumentation

The rapid development of UVRR has been aided by recent advances in lasers, optics and detectors. For temperature-jump (T-jump) measurements an IR pump pulse at 1.9 μm excites the overtone absorption band of water and heats a small sample volume. A time delayed UV probe pulse excites the UVRR of the IR pulse heated volume. The UVRR light is collected and dispersed by a spectrograph and the spectrum is detected by a CCD detector. Non kinetic Raman measurements of static structure are best measured by using CW lasers that avoid nonlinear optical and thermal processes that can induce sample degradation.44

However, high repetition rate (1–5 KHz) pulsed (10–50 nsec) Nd:YLF pumped Ti:Sapphire lasers43,45 are very convenient UVRR laser sources because their output can be easily and continuously tuned between 193 nm to 240 nm. These deep UV excitation beams are generated by frequency quadrupling or tripling and mixing the Ti:Sapphire laser fundamentals. Liquid nitrogen cooled CCD cameras are the optimum UVRR detector because of their low noise.

Protein and Peptide Bond Studies

UV excitation involves the HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals of the peptide bond (secondary amide group, except for proline). The lowest energy n→π* transition at ~210 nm is electronically forbidden and weak. It gives rise to the strong CD signature of the α-helix conformation but gives rise to negligible resonance Raman enhancement.19,46 The ~190 nm π→π* transition is strongly allowed, with a strong absorption band that gives rise to strong UVRR intensities.47 Excitation within this absorption band gives rise to the strong UVRR enhancement of vibrations that have large components of C-N stretching. A somewhat smaller enhancement occurs for vibrations with strong C=O stretching.48

Excitation at ~200 nm gives rise to strong UVRR signals which show particular peptide bond vibrations,49 that include: the Amide I (AmI) vibration (~1660 cm−1) that consists mainly of C=O stretching and a small amount of out-of-phase C-N stretching; the Amide II (AmII) vibration (~1550 cm−1) that consists of an out-of-phase combination of C-N stretching and NH bending motions; and the Amide III (AmIII) vibration (between ~1200 – 1340 cm−1) which is a complex vibration involving C-N stretching and NH bending. A vibration that contains significant Cα-H bending (~1390 cm−1) is also enhanced if the peptide bond conformation causes the coupling of C-H bending to C-N stretching.

These UVRR enhanced peptide bond vibrations (except for the AmI) derive from local modes within individual peptide bonds. The AmI vibrations show small couplings between adjacent peptide bonds.50,51 The local mode character of the AmII, AmIII and Cα-H bending peptide bond vibrations allows the measured UVRR spectrum to be modeled as the linear sum of contributions of the individual peptide bond UVRR spectra.52

This enabled Asher and coworkers to develop a quantitative methodology to determine protein secondary structure directly from the measured UVRR spectra.53 They measured the UVRR spectra of a set of proteins with known x-ray structures and determined the “basis” spectra of the three major secondary structure motifs, the α-helix, β-sheet and unfolded conformations. These basis spectra represent the average pure secondary structure Raman spectra (PSSRS) of α-helix, β-sheet and unfolded conformation.53 The fractional secondary structure composition of a protein with an unknown secondary structure can be uniquely determined by linearly fitting the PSSRS to the protein UVRR spectra. The fitted weighting fractions are the fractional amounts of each secondary structure motif.53

Correlation between spectral features and protein secondary structure

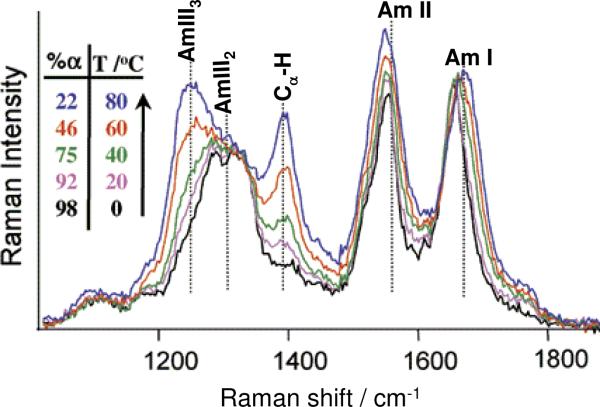

The UVRR spectra of proteins and peptides are conformationally sensitive as shown in the Fig. 2 UVRR study of α-helix melting of poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA) at pH 4. PGA is α-helical at low temperatures, but melts to unfolded structures at high temperatures.54 The α-helix low temperature UVRR spectrum shows an AmI band at ~1660 cm−1, an AmII band at ~1560 cm−1, a (C)Cα-H bending band at ~1390 cm−1, and AmIII bands between ~1200 cm−1 and ~1340 cm−1. As the temperature increases, the AmI band upshifts from ~1660 cm−1 to ~1670 cm−1 and becomes broader, while the AmII band downshifts from ~1560 cm−1 to ~1555 cm−1. These results indicate weakened hydrogen bonding (HB) with increasing temperature. Previous work showed that water HB to the peptide bond C=O site increases the C=O bond length and, thus, downshifts the AmI band, while water HB to the peptide bond N-H upshifts the AmII band. Thus, the extent of HB partially determines the UVRR band frequencies. The Cα-H intensity increase with temperature indicates α-helix melting.53,55 The α-helix conformation shows a negligible Cα-H bending band intensity, in contrast to the unfolded extended conformation that has a high Cα-H bending intensity.53,55

Figure 2.

The temperature dependence of the UVRR spectra and resulting α-helix fractions of poly-L-glutamic acid at pH 4.3 calculated from the UVRR spectra. Adapted from ref. 54.

The AmIII region contains three sub-bands: AmIII1, AmIII2 and AmIII3. However, only two of these sub-bands are clearly resolved in the AmIII region of PGA: the AmIII2 band (~1303 cm−1) and the AmIII3 band (~1250 cm−1). The AmIII3 band, that is most sensitive to conformation, derives from motions that involve coupling of NH bending to Cα-H bending and C-N stretching.56 As the temperature increases, the melted polyproline II (PPII)-like conformation increases and the corresponding unfolded PPII AmIII3 band (~1247 cm−1) in PGA becomes more prominent, overshadowing the low temperature α-helical AmIII3 band. This clearly signals melting of the α-helix conformation to a PPII conformation.

The large AmIII3 band frequency conformational dependence derives from the fact that coupling between Cα-H bending and NH bending peptide bond motion depends sensitively on the peptide bond Ramachandran Ψ dihedral angle that, in part, defines the peptide bond secondary structure conformation.57

Determination of psi (Ψ) angle distribution

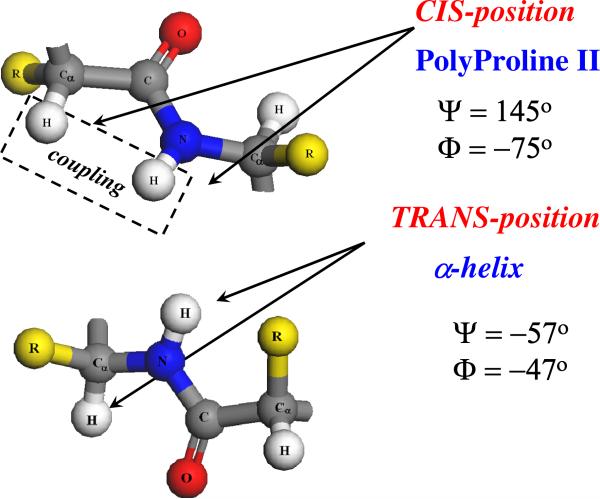

The Asher group discovered a sinusoidal dependence of the AmIII3 frequency on this Ramachandran Ψ angle.54 Conveniently, they also found little dependence of the AmIII3 frequency on the other dihedral angle, the Ramachandran Φ angle (for sterically allowed Ψ angles).56 The origin of this Ψ angle frequency difference between the α-helix and extended conformations results from the fact that the α-helix peptide bond conformations have trans N-H and Cα-H bonds that prevent coupling (Fig. 3). Thus, the α-helix AmIII3 frequency occurs at 1258 cm−1 and the Cα-H band contains negligible C-N and N-H bending motion, and is, thus, not resonance enhanced.

Figure 3.

Relative orientations of N–H and Cα-H bonds in the polyproline II and α-helix conformations.

In contrast, peptide bonds adopting an extended PPII-like conformation have cis N-H and Cα-H bonds whose motions couple well. The AmIII3 band frequency downshifts to 1245 cm−1 and the Cα-H bending vibration contains C-N stretching and N-H bending motion resulting in resonance enhancement.54 Quantitative relations were developed to relate the AmIII3 band frequencies to Ramachandran Ψ angles for different peptide bond HB states.57 For example, for peptide bonds fully hydrogen bonded to water such as in PPII, 2.51-helix, and extended β-strand conformations:

| (1) |

where T is temperature.

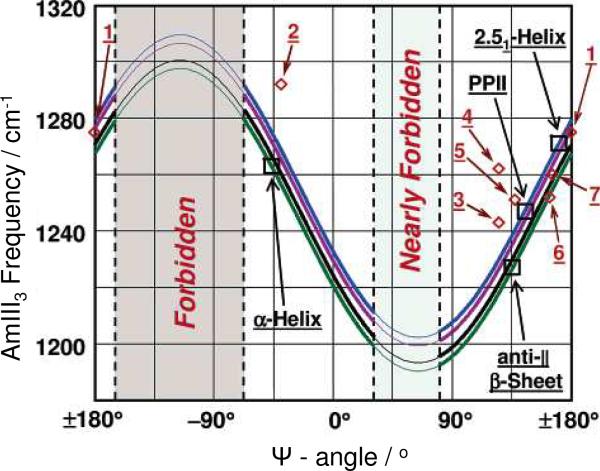

The family of quantitative relationships determining the AmIII3 frequencies ignore the more modest Ramachandran Φ angle dependencies.56 Equations have been proposed to allow estimation of the Ψ angle for the different possible peptide bond HB states. The estimated error of this determination is suggested to be ≤ ± 14°.57 Fig. 4 shows the family of theoretical curves that correlate the AmIII3 frequencies to the Ramachandran Ψ angles for the different HB states.57 As shown below, correlating the inhomogeneously broadened AmIII3 bandshape to the underlying Ramachandran Ψ angle distribution enables the determination of the peptide bond conformational distribution in peptides and proteins. Most importantly, this conformational distribution can be used to calculate the Gibbs free energy landscape along the Ψ angle coordinate, which is the most important (un)folding reaction coordinate.

Figure 4.

Correlation between AmIII3 frequency, peptide bond HB pattern and Ramachandran Ψ angle: (□) measured AmIII3 frequencies of α-helix, antiparallel β-sheet, PPII and 2.51-helix in aqueous solution; (◊) measured AmIII3 frequencies of peptide crystals, plotted against their Ψ angles: 1 Ala-Asp, 2 Gly-Ala-Leu·3H2O, 3 Val-Glu, 4 Ala-Ser, 5 Val-Lys, 6 Ser-Ala, 7 Ala-Ala. Blue curve is the predicted correlation (eq. 1) for full HB to water (PPII, 2.51-helix, and extended β-strand); green curve is a theoretically predicted correlation (eq. 1) for two end-on peptide bond-peptide bond HBs (α-helix-like conformation, and interior strands of β-sheet); magenta curve is the predicted correlation (eq. 1) for peptide bond where only the C=O group has a peptide bond-peptide bond HB (three α-helix N-terminal peptide bond, and half of peptide bonds of the exterior strands of β-sheet); black curve is the predicted correlation (eq. 1) for peptide bond with just their N–H group peptide bond-peptide bond HB (three α-helix C-terminal peptide bond, and the other half of peptide bond of exterior strand of β-sheet). Reproduced from ref. 57.

The UVRR spectra show inhomogeneously broadened Raman bands that reflect the distribution of conformations experienced by the protein. In the case of the AmIII3 band the inhomogeneous distribution reflects mainly the distribution of peptide bond Ψ angles and HB states.

We assume that the experimentally measured, inhomogeneously broadened AmIII3 band, A(ν) derives from the sum of M Lorentzian bands which result from the different peptide bond conformations with different band frequencies, νei.. The AmIII3 band homogeneous linewidth, Γ= 7.5 cm−1 was determined from UVRR measurements of small peptide crystals in defined secondary structure states.58

| (2) |

where Li is the probability for the contributing band to occur at frequency νei.

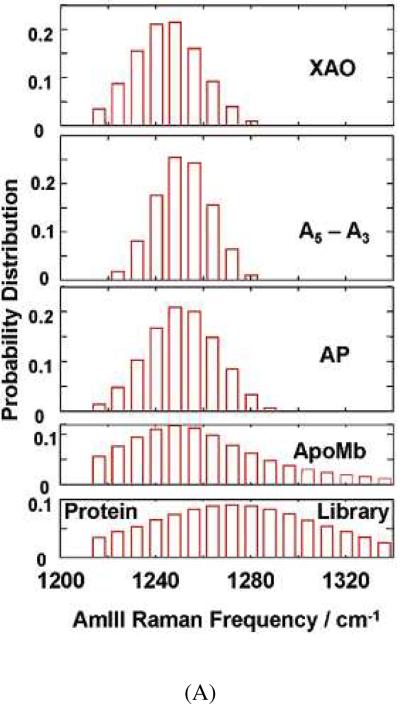

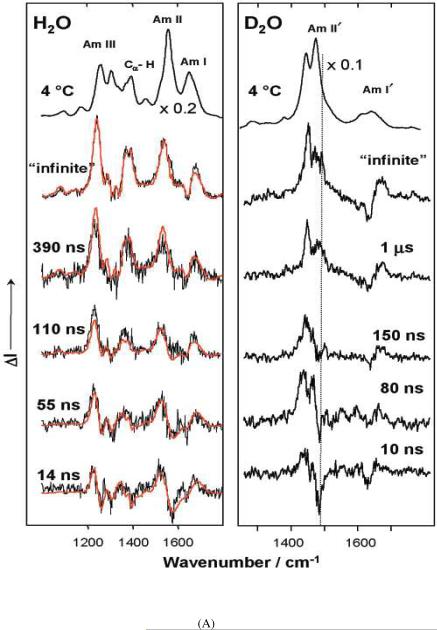

We can deconvolute out the homogeneous linewidth from the peptide bond UVRR spectra to calculate the underlying inhomogeneously broadened AmIII3 band shape,58 leading to the calculation of the frequency distribution of AmIII3 band. We can then use eq. 1, relating the AmIII3 band frequency to the Ramachandran Ψ angle, to convert the frequency distributions to Ψ angle distributions (Fig. 5). Fig. 5A shows histogram plots of the calculated underlying AmIII3 band frequency distributions for a set of peptides and proteins. The XAO peptide of sequence Ac-XXAAAAAAAOO-NH2 (A is alanine, O is ornithine, X is diaminobutyric acid) is known to be primarily in a PPII conformation.59 As shown in Fig. 5A, the XAO frequency distribution is similar to that of A5–A3 (the difference UVRR between ala5 and ala3 that models the spectrum of the interior A5 peptide bonds). This result indicates that these peptide bonds predominantly populate the PPII conformation, as do the peptide bonds of a 21-residue mainly alanine peptide (AP) of sequence, AAAAA(AAARA)3A at elevated temperature. Acid-denatured apomyoglobin shows a broad frequency distribution, as expected, from its broad distribution of conformations. The “protein library”, of course, shows the broadest frequency distribution. Fig. 5B shows the calculated Ramachandran Ψ angle distributions for the samples. These plots are obtained by converting the frequency distributions of Fig. 5A into Ramachandran Ψ angle distributions using eq. 1.

Figure 5.

(A) Frequency distribution of AmIII3 band calculated by deconvolution of homogenously broadened AmIII3 band profiles of XAO of the sequence Ac-XXAAAAAAAOONH2 (A is alanine, O is ornithine, X is diaminobutyric acid), A5–A3 (ala5-ala3), non-α-helical AP of the sequence AAAAA-(AAARA)3A, acid-denatured apomyoglobin, and “disordered” protein conformations. The resulting histogram shows the population distribution underlying the measured AmIII3 band. (B) Estimated Ramachandran Ψ angle distribution of XAO, A5–A3, non-α-helical AP, acid-denatured apomyoglobin, and “disordered” protein conformations. Reproduced from ref. 58.

Further, by applying the Boltzmann relation to the Ψ angle distributions, we can calculate the relative Gibbs free energy along the Ramachandran Ψ angle coordinate since the population at any particular Ψ angle is determined by its relative Gibbs free energy.58 Below we illustrate this approach for AP that melts from an α-helix to a PPII conformation. This approach has also been successfully used to determine the Gibbs free energy landscape for Poly-L-lysine (PLL).55,60

T-jump kinetic studies of protein folding

Dynamic UVRR measurements can be used to elucidate biomolecular structural dynamics.53 UVRR T-jump measurements can elucidate the evolution of peptide and protein secondary structure.61–70 These studies probe the evolution between different secondary structural motifs such as α-helix, 310-helix, π-bulge and PPII conformations.71 The rates of these transitions occur in the 100 nsec to ~ 2 μsec time regime.

Recent nsec to μsec protein folding dynamics studies find complex unfolding behaviors. For example, recent studies of the mainly alanine peptide (AP) melting demonstrate a complex pathway that involves melting of multiple α-helix-like structures, which include the 310-helix, π-bulge and pure α-helix conformations that have different melting curves to the PPII-like unfolded conformation.63

To gain insight into the dynamics of protein (un)folding, the Asher group constructed the first T-jump UVRR spectrometer that they used to examine conformational relaxation subsequent to nsec T-jumps.63 The peptide and protein relaxation after the T-jump utilizes folding and unfolding conformational change coordinates that are easily studied with UVRR. These T-jumps used ~5 nsec excitation pulses at 1.9 μm that occur within a water vibrational overtone absorption band. Thermalization of the absorbed energy occurs within 70 ps.72,73 It is easy to achieve ~20 °C T-jumps from the ~5 nsec IR laser pulses.

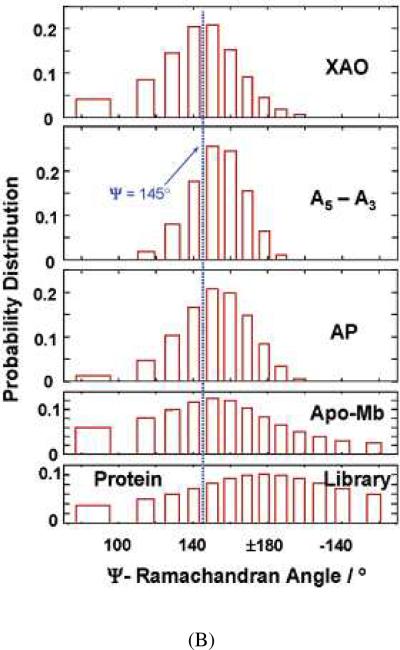

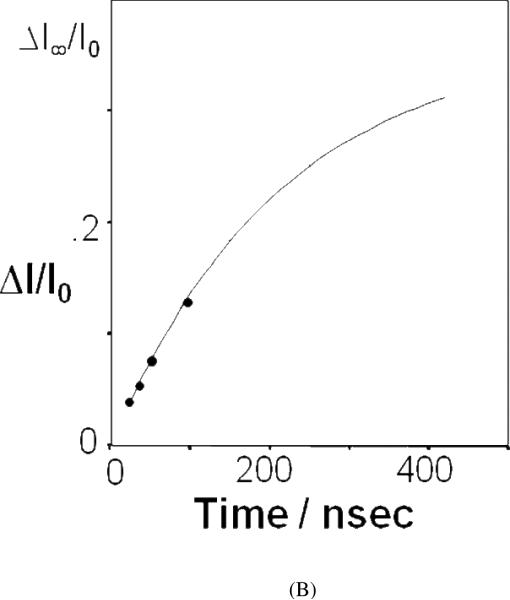

In their first kinetic studies, the Asher group examined the kinetics of melting of the AP that at low temperature is mainly α-helical.63 Steady state measurements showed that the α-helix melts to a PPII conformation. Fig. 6A shows the T-jump relaxation transient difference UVRR spectra of AP in H2O and D2O. The transient difference spectra measured at delay times as long as 1 μsec were modeled using a linear combination of α-helix and the PPII equilibrium UVRR basis spectra. The first spectral changes evident at <10 nsec derives from fast HB changes of water bound to the peptide bonds in the PPII state due to the temperature increase.61

Figure 6.

(A) AP UVRR spectra measured in water and D2O solution at 4 °C (top), and transient difference spectra of AP in solution initially at 4 °C measured at different delay times following a T-jump of ~31 °C (~22 °C in D2O). (B) Kinetics of thermal denaturation of AP. The ordinate axis is the relative change in the UV Raman intensity at 1236 cm−1 obtained from transient difference spectra of Fig. 14 of ref. 62. The abscissa is the time delay at which the spectra were acquired following the T-jump. Reproduced from refs. (A) 61 and (B) 62.

Subsequent relaxation spectral changes result from peptide bond conformation changes. Modeling of the transient spectra can determine the kinetics of the AP structural relaxation. Depending on the initial temperature, unfolding time constants between 180 and 240 ns were observed. By assuming a 2-state model they calculated a folding time constant of ~1 μs (Fig. 6).61–63

They also observed a puzzling peculiarity in the temperature dependence of the folding and unfolding rate constants that they calculated from the relaxation rates by assuming a 2-state system (that was fully consistent with the observed single exponential relaxation behavior). As the temperature increased, they calculated that the folding rate constant decreased, indicating a negative activation energy of kcal/mol, that indicates an anti-Arrhenius behavior.62,63 Obviously, this peculiarity must result from the fact that the conformational transition is not 2-state.

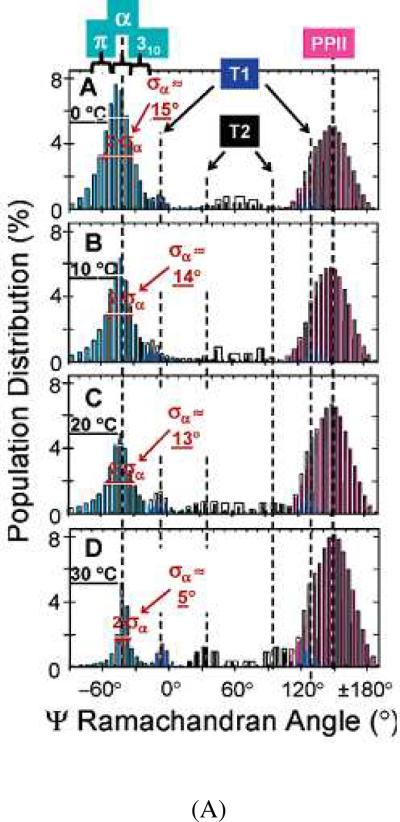

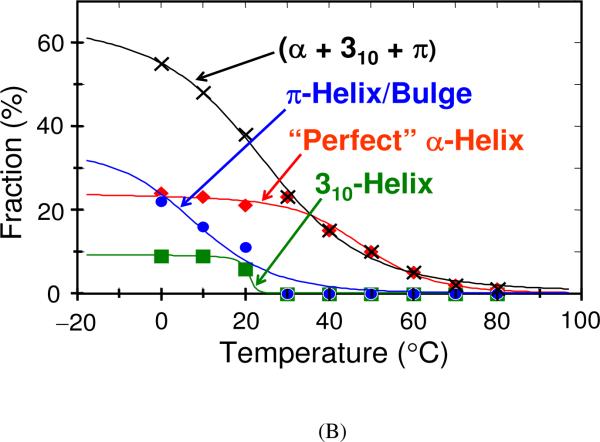

Subsequently, Mikhonin et al identified the additional states involved in the melting transition.74 They found that they could spectrally differentiate α-helix-like conformational substates from the AmIII3 band frequency distribution. They calculated the α-helix-like UVRR spectrum by subtracting off the pure PPII UVRR spectrum measured at higher temperature (after accounting for the temperature dependence of the PPII UVRR spectrum). Fig. 7A shows the calculated Ramachandran angle distributions in AP between 0°C and 30 °C.

Figure 7.

(A) Calculated Ramachandran Ψ probability distributions in AP at (A) 0 °C, (B) 10 °C, (C) 20 °C, (D) 30 °C. Reproduced from ref. 74. (B) Melting curves for AP “α-helix-like” conformations. (×) – Original “α-helix” melting curve as reported by Lednev et al. (refs. 62 and 61), which is a sum of individual α- π- and 310-helical melting curves; (◇) – Pure α-helix melting; (■) – 310-helix (type III turn) melting; (●) – π-bulge (π-helix) melting. Adapted from ref. 74.

At low temperatures, the Ψ angle distribution of the α-helix-like state is broad and spans the Ψ angles of the pure α-helix, 310-helix and π-helix bulge conformations. As the temperature increases the α-helix-like Ψ angle distribution narrows until at 30 °C, the distribution becomes very narrow and centered at −42°, the Ψ angle of the pure α-helix.

Fig. 7B shows the melting curves determined for these different α-helix-like conformations by assuming identical Raman cross sections for the pure α-helix, the 310-helix and the π-bulge conformations. Tm was determined to be 45 °C, 20 °C and 10 °C for the α-helix, 310-helices and π-bulges, respectively.

The anti-Arrhenius behavior observed by Lednev et al's T-jump measurements directly results from these different Tm for the 310-helix, π-bulge and pure α-helix conformations.75 As the temperature increases the pure α-helix conformation increasingly dominates the equilibrium conformational distribution. Apparently, the folding rate of the pure α-helix conformation is slowest. These studies clearly show the utility of UVRR to gain crucial insight into the complex nature of peptide folding dynamics.

These types of T-jump studies can give important biological insight. For example, in a recent protein T-jump study, Spiro et al70 examined the early events in the unfolding of apomyoglobin using both 197 and 229 nm excitation. These excitations allowed them to probe both the aromatic side chains and the peptide backbone conformations. Aromatic amino acid side chain UVRR bands can monitor the solvent exposure, while the peptide bond UVRR bands report on backbone Ramachandran Ψ angles, as discussed above. Measuring both spectral bands can answer the question of whether a changing solvent exposure of the protein core precedes or follows secondary structure changes. The authors were able to clearly differentiate the order of these events. They found that the Trp14 bands respond twice as fast as does the peptide bond α-helix melting. Thus, Trp14 that is originally buried in the protein core becomes exposed to solvent prior to melting of the protein core.

Kinetic IR T-jump experiments have also been carried out on α-helical peptides.22,76 For instance, in their IR studies, the Dyer group found that suc-Fs 21-peptide (a peptide very similar to AP) shows fast unfolding kinetics with a time constant of ~160 ns.22 This result is consistent with the UVRR studies of Lednev, et al.63 In another IR T-jump kinetic study, the Gai group examined the helix-coil transition of an α-helical peptide and its deuterated analog, Ac-YGSPEA3KA4KA4-CO-D-Arg-CONH2 and Ac-YGSPEA3KAAAAKA4-CO-D-Arg-CONH2, where the underlined residues are 13C-labeled. This design was meant to use the 13C=O AmI band of the central ala residues to probe conformational changes associated with only the middle of the peptide sequence and to discriminate it from signals due to end-fraying. They reported a complex helix-coil transition that does show single exponential relaxation.76 Their multiexponential relaxation kinetics based on 13C=O AmI band changes show a component with a time constant of 230 ns similar to ours, that does not arise from end-fraying.22,63 The IR peptide folding dynamic studies show less information content since they only monitor the AmI band,22,76 whereas UVRR monitors the Cα-H, AmII and AmIII bands, in addition to the AmI band. Thus, UVRR can give a more informative picture of peptide folding dynamics. Further, as shown in Fig. 2 the spectral dependence of the AmI band is less than for the AmIII3 and the Cα-H bending bands.

Other UVRR Insights

A number of other recent UVRR studies have also illustrated the important protein information available. For example, Ianoul et al used UVRR to examine the peptide backbone spatial dependence of α-helix melting of deuterium labeled AP (AdP).71 In AdP, all the ala residues except the four central ones were selectively deuterated. They found that melting of the isotopically labeled exterior peptide bonds could be spectrally resolved from the central ones; thus, allowing the spatial resolution of the peptide bond conformational changes. The results show that the central residues are essentially 100 % α-helix-like at 0 °C with a Tm of 32 °C while the exterior residues are ~60 % α-helix-like at 0 °C with a Tm of 5 °C.

More recently, Lednev's group reported the application of UVRR for studying amyloid fibrils,77,78 which are well-organized protein aggregates associated with many neurodegenerative diseases. Amyloid fibrils are not soluble and do not form crystals, limiting the application of conventional NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography, two major biophysical tools of structural biology. UVRR spectroscopy is uniquely suitable for characterizing the protein structure at all stages of fibrillation. Chemometric79 and 2D correlation80 analysis of UVRR spectra allowed for direct monitoring of the fibrillation nucleus,81 establishing the sequential order of changes in the protein secondary structure and the kinetic mechanism of lysozyme fibrillation.82

Their combination of hydrogen-deuterium exchange with UVRR and advanced statistics enabled them to determine the spectroscopic signature of the fibril core.83 They then utilized our method described above to determine the Ramachandran Ψ angle distribution in the fibril core.84,85 This information is a powerful constraint for determining the conformation of β-strands in the fibril core. This approach is the only experimental tool available at the moment to directly characterize the cross-β core structure in fibrils prepared from the full-length proteins. X-ray crystallography of small peptide microcrystals mimicking the fibril core and solid state NMR of fibrils, prepared from isotope labeled peptides can provide the atomic-resolution structure of the fibril core. UVRR – hydrogen-deuterium exchange indicated a significant variability in the core structure of fibrils prepared from different proteins.84,85 In addition, it allowed differentiating parallel and antiparallel β-sheets in the cross-β core of Amyloid β fibrils.84 Moreover, the conformation of the parallel β-sheet in the A1–40 fibril core was atypical for globular proteins, while in contrast, the antiparallel β-sheet in A32–42 fibrils was a common structure in globular proteins.84 Consistent with the latter observation, the Raman signature of the fibrillar-type β-sheet was required in addition to the globular protein β-sheet to satisfactorily fit the UVRR spectra of the aggregated prion protein.86

Future Direction and Outlook

The UVRR methodologies discussed in this perspective enable incisive investigations into the mechanism of protein folding. Future studies will include single peptide bond conformational changes and studies of the conformation of sidechains such as phe, tyr, trp, arg, asn and gln.

Resolution of individual peptide bond conformational changes

The current state-of-the-art UVRR measurements lack sufficient S/N to monitor conformational changes at the single peptide bond level of a ~100 residue protein. However, UVRR instrumentation continues to advance due to improvements in laser technology and the development of UV Raman spectrometers with dramatically improved spectral dispersion that enable dramatically increased throughput. We are constructing a spectrometer which utilizes very high dispersion gratings with optics specially coated for deep UV efficiencies. The increased S/N will enable the monitoring of the Gibbs free energy landscape of individual peptide bonds in a peptide or protein. Cα deuteration silences the Ψ angle dependence of the AmIII3 band frequency. Thus, the difference UVRR between a Cα deuterium labeled and the natural abundance protein reveals the AmIII3 band of the labeled peptide bond; the frequencies and bandshapes reveal its Ramachandran Ψ angle distribution, which reveals its Gibbs free energy landscape. T-jump kinetic measurements of the isotope labeled difference spectra will reveal the individual peptide bonds activation barriers that control (un)folding mechanisms.

Amino acid side chain conformations

There are numerous amino acid side chains chromophores that show UVRR enhanced bands with ~200 nm UVRR excitation. These UVRR bands can be used to monitor amino acid side chain conformations and their interactions with other side chains and the backbone peptide bonds. There is now a deep understanding of the conformational dependence of the trp, tyr and phe aromatic amino acids UVRR spectra.87,88 In contrast, there are few studies of the UVRR bands of his residues89 and no published studies, to our knowledge, of arg, asn and gln residues. The asn and gln side chains give rise to UVRR enhanced primary amide UVRR bands that partially overlap the peptide bond amide bands. These can be selectively monitored by comparing very deep UV ~195 nm UVRR, for example, to UVRR spectra excited at 204 nm; primary amides show their π→π* transition at shorter wavelength than the peptide bond π→π* transition.90 Thus, appropriately scaled 195 nm – 204 nm difference spectra will display the side chain primary amide bands.

We are now characterizing the UVRR spectra of asn and gln side chain vibrations in order to determine their HB dependence. This will ultimately enable UVRR to detect HB of side chains in peptides and proteins. The arg side chain shows an isolated band at 1178 cm−1 which is easily observed in AP, for example.46 Our work is also investigating the role of arg residues in α-helix stabilization.

Conclusion

The unique utility of UVRR for the study of protein folding is discussed in this perspective. Specifically, we have shown how peptide bond resonance Raman enhancement permits the study of protein secondary structure by using ~200 nm UV excitation. It now is clear that UVRR is the most useful dilute solution method to quickly determine protein and peptide secondary structure. The sinusoidal dependence of the AmIII3 Raman band frequency on the Ramachandran Ψ angle enables the determination of solution peptide bond Ψ angle distributions. The measurement of this distribution reveals the Gibbs free energy landscape along the Ψ angle protein (un)folding coordinate. Kinetic T-jump studies allow the examination of the kinetics of protein folding and reveal aspects of the activation barriers between equilibrium conformations. The application of UVRR to the study of formation mechanism of amyloid fibrils is an important illustration of the power of the technique to probe structure and dynamics. The development of statistical methods for the analysis of UVRR spectra dramatically increases the information content of the spectroscopy.

Quotes.

Another advantage of deep UV Raman measurements is that there is no interference from molecular relaxed fluorescence.

UVRR T-jump measurements monitored by UVRR measurements can elucidate the evolution of peptide and protein secondary structure.

To gain insight into the dynamics of protein (un)folding, the Asher group constructed the first T-jump UVRR spectrometer that they used to examine conformational relaxation subsequent to nsec T-jumps.

The increased S/N will enable the monitoring of the Gibbs free energy landscape of individual peptide bonds in a peptide or protein.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully thank Igor Lednev for helping us properly describe his groups fibrillation studies. We also gratefully acknowledge NIH Grant # 1R01EB009089 for funding.

Biographies

Sulayman Oladepo received his PhD from the University of Alberta, under the supervision of Prof. Glen Loppnow. He is currently doing his postdoctoral work in the laboratory of Prof. Sanford Asher at the University of Pittsburgh. His current research involves the use of UV resonance Raman spectroscopy to study the melting dynamics of β-sheet structures and the effects of citrullination on protein folding dynamics.

Kan Xiong received his Bachelor's Degree in Chemistry from the University of Science and Technology of China in 2006. He is currently a senior graduate student under the direction of Prof. Sanford A. Asher at the University of Pittsburgh and is working on using UV resonance Raman spectroscopy to study protein and peptide folding.

Zhenmin Hong is currently a graduate student in the Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh. He received B.S. and M.S. degrees from Tsinghua University, China. His research interest includes using UV resonance Raman spectroscopy to study protein and peptide structure and folding. He is now examining the effect of side chain interactions on determining peptide conformations.

Sanford Asher is Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at the University of Pittsburgh. He received his Bachelor's degree from the University of Missouri at St. Louis in 1971 and his PhD in 1977 from UC Berkeley. Following a postdoctoral work in Applied Physics at Harvard, he joined the department of Chemistry of the University of Pittsburgh in 1980. His current research concentrates on developing UV resonance Raman spectroscopy for probing protein structure and dynamics. His research group also investigates and develops photonic crystal materials and sensors. See http://www.pitt.edu/~asher/homepage/index.html

References

- 1.Baldwin RL, Rose GD. Is Protein Folding Hierarchic? I. Local Structure and Peptide Folding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:26–33. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin RL, Rose GD. Is Protein Folding Hierarchic? II. Folding Intermediates and Transition States. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobson CM. The Structural Basis of Protein Folding and Its Links with Human Disease. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. Lond. Ser. B-Biol. Sci. 2001;356:133–145. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobson CM, Sali A, Karplus M. Protein Folding: A Perspective from Theory and Experiment. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 1998;37:868–893. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980420)37:7<868::AID-ANIE868>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahn TR, Radford SE. The Yin and Yang of Protein Folding. FEBS. 2005;272:5962–5970. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindberg MO, Oliveberg M. Malleability of Protein Folding Pathways: A Simple Reason for Complex Behaviour. Curr. Op. Struc. Biol. 2007;17:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daggett V, Fersht A. The Present View of the Mechanism of Protein Folding. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:497–502. doi: 10.1038/nrm1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anfinsen CB, Haber E, Sela M, White FH., Jr. The Kinetics of Formation of Native Ribonuclease During Oxidation of the Reduced Polypeptide Chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1961;47:1309–1314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.9.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews CR. Pathways of Protein-Folding. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:653–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thirumalai D, Woodson SA. Kinetics of Folding of Proteins and RNA. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996;29:433–439. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim PS, Baldwin RL. Specific Intermediates in the Folding Reactions of Small Proteins and the Mechanism of Protein Folding. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1982;51:459–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karplus M, Weaver DL. Protein Folding Dynamics. Nature. 1976;260:404–406. doi: 10.1038/260404a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daggett V, Fersht AR. Is There a Unifying Mechanism for Protein Folding? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dill KA, Chan HS. From Levinthal to Pathways to Funnels. Nature Struct. Biol. 1997;4:10–19. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mello CC, Barrick D. An Experimentally Determined Protein Folding Energy Landscape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:14102–14107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403386101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacKerell AD, Jr., Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Jr., Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, et al. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantor CR, Schimmel PR. Absorption Spectroscopy. In: McCombs LW, editor. Biophysical Chemistry. Vol. 2. W. H. Freeman and Company; San Francisco: 1980. pp. 349–408. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenheck K, Doty P. The Far Ultraviolet Absorption Spectra of Polypeptide and Protein Solutions and Their Dependence on Conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1961;47:1775–1785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.11.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallenbach NR, Lyu P, Zhou H. CD Spectroscopy and the Helix-Coil Transition in Peptides and Polypeptides. In: Fasman GD, editor. Circular Dichroism and Conformational Analysis of Biomolecules. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. pp. 201–259. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittermaier A, Kay LE. Review - New Tools Provide New Insights in NMR Studies of Protein Dynamics. Science. 2006;312:224–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1124964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wuthrich K. NMR - This Other Method for Protein and Nucleic-Acid Structure Determination. Acta Cryst. D Biol. Cryst. 1995;51:249–270. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994010188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams S, Causgrove TP, Gilmanshin R, Fang KS, Callender RH, Woodruff WH, Dyer RB. Fast Events in Protein Folding: Helix Melting and Formation in a Small Peptide. Biochemistry. 1996;35:691–697. doi: 10.1021/bi952217p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendra PJ. Sampling Consideration for Raman Cpectroscopy. In: Chalmers JP, Griffiths PR, editors. Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons; London: 2002. pp. 1263–1288. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everall NJ. Raman Spectroscopy of the Condensed Phase. In: Chalmers JP, Griffiths PR, editors. Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; London: 2002. pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber A. Raman Spectroscopy of Gases. In: Chalmers JP, Griffiths PR, editors. Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; London: 2002. pp. 176–194. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long DA. The Raman Effect: A Unified Treatment of the Theory of Raman Scattering by Molecules. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; West Sussex, England: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramers H, Heisenberg W. Über die Streuung von Strahlung durch Atome. Zeitschrift für Physik A Hadrons and Nuclei. 1925;31:681–708. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dirac PAM. The Quantum Theory of Dispersion. Proc. Royal Soc. Lond. A. 1927;114:710–728. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Placzek G. Rayleigh and Raman Scattering. In: Marx E, editor. Handbuch der Radiologie. Vol. 6. Aeademische; Leipzig: 1934. p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albrecht AC. On the Theory of Raman Intensities. J. Chem. Phys. 1961;34:1476–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S-Y, Heller EJ. Time-Dependent Theory of Raman Scattering. J. Chem. Phys. 1979;71:4777–4788. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tannor DJ, Heller EJ. Polyatomic Raman Scattering for General Harmonic Potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 1982;77:202–218. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heller EJ, Sundberg R, Tannor D. Simple Aspects of Raman Scattering. J. Phys. Chem. 1982;86:1822–1833. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Studies of Molecular Structure and Dynamics: Applications in Physical and Biophysical Chemistry. Annu. Rev.Phys. Chem. 1988;39:537–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pc.39.100188.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers AB. `Time-Dependent' Resonance Raman Theory. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1997;28:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asher SA. UV resonance Raman-Spectroscopy for Analytical, Physical, and Biophysical Chemistry .1. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:A59–A66. doi: 10.1021/ac00052a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asher SA. UV resonance Raman-Spectroscopy for Analytical, Physical, and Biophysical Chemistry .2. Anal. Chem. 1993;65:A201–A210. doi: 10.1021/ac00052a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palaniappan V, Bocian DF. Acid-Induced Transformations of Myoglobin. Characterization of a New Equilibrium Heme-Pocket Intermediate. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14264–14274. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chi ZH, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Determination of Protein Acid Denaturation: Selective Unfolding of Helical Segments of Horse Myoglobin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2865–2872. doi: 10.1021/bi971161r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Oyerinde OF, Su J, Groves JT, Spiro TG. A Conformational Switch to β-Sheet Structure in Cytochrome C Leads to Heme Exposure. Implications for Cardiolipin Peroxidation and Apoptosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:504–505. doi: 10.1021/ja0678727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed Z, Beta IA, Mikhonin AV, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Thermal Unfolding Study of Trp-Cage Shows That it is Not a Simple Two-State Miniprotein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10943–10950. doi: 10.1021/ja050664e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asher SA, Johnson CR. Raman Spectroscopy of a Coal Liquid Shows that Fluorescence Interference is Minimized with Ultraviolet Excitation. Science. 1984;225:311–313. doi: 10.1126/science.6740313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bykov S, Lednev I, Ianoul A, Mikhonin A, Munro C, Asher SA. Steady-State and Transient Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectrometer for the 193–270 nm Spectral Region. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005;59:1541–1552. doi: 10.1366/000370205775142511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asher SA, Bormett RW, Chen XG, Lemmon DH, Cho N, Peterson P, Arrigoni M, Spinelli L, Cannon J. UV Resonance Raman-Spectroscopy Using a New CW Laser Source - Convenience and Experimental Simplicity. Appl. Spectrosc. 1993;47:628–633. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao XJ, Chen RP, Tengroth C, Spiro TG. Solid-State Tunable kHz Ultraviolet Laser for Raman Applications. Appl. Spectrosc. 1999;53:1200–1205. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma B, Bykov SV, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Investigation of Electronic Transitions in α-Helical and Polyproline II-Like Conformations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:11762–11769. doi: 10.1021/jp801110q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asher SA, Chi ZH, Li PS. Resonance Raman Examination of the Two Lowest Amide ππ* Excited States. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1998;29:927–931. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen XG, Asher SA, Schweitzerstenner R, Mirkin NG, Krimm S. UV Raman Determination of the π-π* Excited-State Geometry of N-Methylacetamide - Vibrational Enhancement Pattern. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:2884–2895. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myshakina NS, Asher SA. Peptide Bond Vibrational Coupling. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:4271–4279. doi: 10.1021/jp065247i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mix G, Schweitzer-Stenner R, Asher SA. Uncoupled Adjacent Amide Vibrations in Small Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9028–9029. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mikhonin AV, Asher SA. Uncoupled Peptide Bond Vibrations in α-Helical and Polyproline II Conformations of Polyalanine Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:3047–3052. doi: 10.1021/jp0460442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bykov SV, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Elucidation of the Terminal and Internal Peptide Bond Conformations of Crystalline and Solution Oligoglycines. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:269–271. doi: 10.1021/jz900117u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chi ZH, Chen XG, Holtz JSW, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman-Selective Amide Vibrational Enhancement: Quantitative Methodology for Determining Protein Secondary Structure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2854–2864. doi: 10.1021/bi971160z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asher SA, Ianoul A, Mix G, Boyden MN, Karnoup A, Diem M, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Dihedral Ψ Angle Dependence of the Amide III Vibration: A Uniquely Sensitive UV Resonance Raman Secondary Structural Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11775–11781. doi: 10.1021/ja0039738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma L, Ahmed Z, Mikhonin AV, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Measurements of Poly-L-Lysine's Conformational Energy Landscapes: Dependence on Perchlorate Concentration and Temperature. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7675–7680. doi: 10.1021/jp0703758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ianoul A, Boyden MN, Asher SA. Dependence of the Peptide Amide III Vibration on the Φ Dihedral Angle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7433–7434. doi: 10.1021/ja0023128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mikhonin AV, Bykov SV, Myshakina NS, Asher SA. Peptide Secondary Structure Folding Reaction Coordinate: Correlation Between UV Raman Amide III Frequency, Ψ Ramachandran Angle, and Hydrogen Bonding. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:1928–1943. doi: 10.1021/jp054593h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asher SA, Mikhonin AV, Bykov SV. UV Raman Demonstrates that α-Helical Polyalanine Peptides Melt to Polyproline II Conformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8433–8440. doi: 10.1021/ja049518j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi Z, Olson C, Rose G, Baldwin R, Kallenbach N. Polyproline II Structure in a Sequence of Seven Alanine Residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:9190–9195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112193999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mikhonin AV, Myshakina NS, Bykov SV, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Determination of Polyproline II, Extended 2.51-Helix, and β-Sheet Ψ Angle Energy Landscape in Poly-L-Lysine and Poly-L-Glutamic Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7712–7720. doi: 10.1021/ja044636s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lednev IK, Karnoup AS, Sparrow MC, Asher SA. Transient UV Raman Spectroscopy Finds No Crossing Barrier Between the Peptide α-Helix and Fully Random Coil Conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2388–2392. doi: 10.1021/ja003381p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lednev IK, Karnoup AS, Sparrow MC, Asher SA. α-Helix Peptide Folding and Unfolding Activation Barriers: A Nanosecond UV Resonance Raman Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8074–8086. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lednev IK, Karnoup AS, Sparrow MC, Asher SA. Nanosecond UV Resonance Raman Examination of Initial Steps in α-Helix Secondary Structure Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4076–4077. [Google Scholar]

- 64.JiJi RD, Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Spiro TG. Intermediacy of Poly(L-proline) II and β-Strand Conformations in Poly(L-lysine) β-sheet Formation Probed by Temperature-Jump/UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:34–41. doi: 10.1021/bi051507v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Bender GM, Getahun Z, DeGrado WF, Spiro TG. Nanosecond T-Jump Induced Unfolding Kinetics of α-Helical Peptide: A UV Resonance Raman Study. Biophysical J. 2005;88:39A–40A. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Bender GM, Getahun Z, DeGrado WF, Spiro TG. Enthalpic and Entropic Stages in α-Helical Peptide Unfolding, from Laser T-Jump/UV Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12801–12808. doi: 10.1021/ja073366l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Case MA, McLendon GA, Spiro TG. T-Jump Induced Helix to Coil Transition in GCN4 Derivative, A Model Coiled-Coil System: UV Raman Study. Biophysical J. 2004;86:499A–500A. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Case MA, Spiro TG. Microsecond Melting of a Folding Intermediate in a Coiled-Coil Peptide, Monitored by T-Jump/UV Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:19877–19883. doi: 10.1021/jp061987f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balakrishnan G, Hu Y, Spiro TG. Temperature-Jump Apparatus with Raman Detection Based on a Solid-State Tunable (1.80–2.05 μm) kHz Optical Parametric Oscillator Laser. Appl. Spectrosc. 2006;60:347–351. doi: 10.1366/000370206776593799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang CY, Balakrishnan G, Spiro TG. Early Events in Apomyoglobin Unfolding Probed by Laser T-jump/UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15734–15742. doi: 10.1021/bi051578u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ianoul A, Mikhonin A, Lednev IK, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Study of the Spatial Dependence of α-Helix Unfolding. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:3621–3624. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Phillips CM, Mizutani Y, Hochstrasser RM. Ultrafast Thermally-Induced Unfolding of RNase-A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1995;92:7292–7296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lian TL,B, Kholodenko Y, Hochstrasser M. Energy Flow from Solute to Solvent Probed by Femtosecond IR Spectroscopy: Malchite Green and Heme Protein Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11648–11656. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mikhonin AV, Asher SA. Direct UV Raman Monitoring of 310-Helix and π-Bulge Premelting During α-Helix Unfolding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13789–13795. doi: 10.1021/ja062269+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mikhonin A, Asher S, Bykov S, Murza A. UV Raman Spatially Resolved Melting Dynamics of Isotopically Labeled Polyalanyl Peptide: Slow α-Helix Melting Follows 310-Helices and π-Bulges Premelting. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:3280–3292. doi: 10.1021/jp0654009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang C-Y, Getahun Z, Wang T, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Time-Resolved Infrared Study of the Helix-Coil Transition Using 13C-Labelled Helical Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12111–12112. doi: 10.1021/ja016631q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lednev IK, Shashilov V, Xu M. Ultraviolet Raman Spectroscopy is Uniquely Suitable for Studying Amyloid Diseases. Curr. Sci. 2009;97:180–185. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu M, Ermolenkov VV, Uversky VN, Lednev IK. Hen Egg White Lysozyme Fibrillation: A Deep-UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopic Study. J. Biophoton. 2008;1:215–229. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200710013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shashilov VA, Lednev IK. Advanced Statistical And Numerical Methods for Spectroscopic Characterization of Protein Structural Evolution. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:5692–713. doi: 10.1021/cr900152h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shashilov VA, Lednev IK. Two-Dimensional Correlation Raman Spectroscopy for Characterizing Protein Structure and Dynamics. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009;40:1749–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shashilov V, Xu M, Ermolenkov VV, Fredriksen L, Lednev IK. Probing a Fibrillation Nucleus Directly by Deep Ultraviolet Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6972–6973. doi: 10.1021/ja070038c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shashilov VA, Lednev IK. 2D Correlation Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Early Events of Lysozyme Fibrillation: Kinetic Mechanism and Potential Interpretation Pitfalls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:309–317. doi: 10.1021/ja076225s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu M, Shashilov V, Lednev IK. Probing the Cross-β Core Structure of Amyloid Fibrils by Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Deep Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11002–11003. doi: 10.1021/ja073798w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Popova LA, Kodali R, Wetzel R, Lednev IK. Structural Variations in the Cross-β Core of Amyloid β Fibrils Revealed by Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6324–6328. doi: 10.1021/ja909074j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sikirzhytski V, Topilina NI, Higashiya S, Welch JT, Lednev IK. Genetic Engineering Combined with Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy for Structural Characterization of Amyloid-Like Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5852–5853. doi: 10.1021/ja8006275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shashilov VA, Sikirzhytski V, Popova LA, Lednev IK. Quantitative Methods for Structural Characterization of Proteins Based on Deep UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Methods. 2010;52:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Asher SA. Ultraviolet Raman Spectroscopy. In: Chalmers JP, Griffiths PR, editors. Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; London: 2002. pp. 557–571. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kneipp J, Balakrishnan G, Chen R, Shen TJ, Sahu SC, Ho NT, Giovannelli JL, Simplaceanu V, Ho C, Spiro TG. Dynamics of Allostery in Hemoglobin: Roles of the Penultimate Tyrosine H-Bonds. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;256:335–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu Q, Balakrishnan G, Pevsner A, Spiro TG. Histidine Photodegradation During UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:8047–8051. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dudik JM, Johnson CR, Asher SA. UV Resonance Raman Studies of Acetone, Acetamide, and N-Methylacetamide: Models for the Peptide Bond. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:3805–3814. [Google Scholar]