Abstract

Lysine propionylation is a recently identified post-translational modification that has been observed in proteins such as p53 and histones and is thought to play a role similar to acetylation in modulating protein activity. Members of the sirtuin family of deacetylases have been shown to have depropionylation activity, although the way in which the sirtuin catalytic site accommodates the bulkier propionyl group is not clear. We have determined the 1.8 Å structure of a Thermotoga maritima sirtuin, Sir2Tm, bound to a propionylated peptide derived from p53. A comparison with the structure of Sir2Tm bound to an acetylated peptide shows that hydrophobic residues in the active site shift to accommodate the bulkier propionyl group. Isothermal titration calorimetry data show that Sir2Tm binds propionylated substrates more tightly than acetylated substrates, but kinetic assays reveal that the catalytic rate of Sir2Tm deacylation of propionyl-lysine is slightly reduced to acetyl-lysine. These results serve to broaden our understanding of the newly identified propionyl-lysine modification and the ability of sirtuins to depropionylate, as well as deacetylate, substrates.

Keywords: Sir2, sirtuin, propionyl-lysine, depropionylation, deacetylation, T. maritima

Introduction

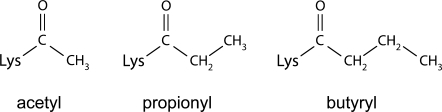

Protein acetylation is a dynamic, reversible post-translational modification that regulates many different biological pathways. The acetylation status of various lysine residues on histones governs chromatin structure and regulates transcription, whereas acetylation of metabolic enzymes, such as acetyl-CoA synthetase, has been found to regulate their activity.1 Recent studies have identified the presence of two novel acyl modifications of lysine, propionylation and butyrylation,2 in proteins such as histones,2 propionyl-CoA synthetase,3 and p53.4 These modifications are chemically similar to acetylation but have one or two extra methylene groups, respectively, making the modifications bulkier and more hydrophobic (Fig. 1). Like acetyltransferases, which use acetyl-CoA as the acetyl group donor, propionyltransferases and butyryltransferases catalyze transfer of the acyl group from propionyl-CoA and butyryl-CoA, respectively, to the ɛ-nitrogen of lysine. Previously identified acetyltransferases such as the GCN5 family of acetyltransferases and P300 can utilize either acetyl-CoA or propionyl-CoA to acetylate or propionylate substrates, respectively.3,4 Although less is known about the role of the propionyl and butyryl modifications, they are likely to serve a function similar to acetylation in regulating complex biological networks. In an example where a biological role for this modification has been well-established, propionylation of Salmonella enterica propionyl-CoA synthetase inactivates the enzyme,3 thereby serving as a negative regulator of propionyl-CoA synthesis, much in the way that acetylation regulates the activity of acetyl-CoA synthetase.1

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of acetyl (left), propionyl (middle), and butyryl (right) modifications.

Protein acetylation is reversed by lysine deacetylase enzymes, which remove the acetyl group to regenerate an unmodified lysine residue. Sir2 enzymes (sirtuins) are NAD+-dependent lysine deacetylases that cleave NAD+ during deacetylation, releasing nicotinamide and the metabolite, O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (OAADPR), as products.5,6 Sirtuins have been shown to deacetylate histones,7 p53,8,9 α-tubulin,10 and acetyl-CoA synthetase1 and regulate numerous biological processes, including transcriptional repression,11 rDNA recombination,12,13 apoptosis,9 fat mobilization,14 and metabolism.1 Sirtuins have in common a conserved catalytic core15–21 and are found in all three domains of life, with many organisms possessing multiple sirtuin homologs.11,22 Although deacetylation is the principal activity of most sirtuins, not all sirtuins have been shown to deacetylate lysines, and some sirtuins can catalyze other reactions. Indeed, sirtuins were first identified as ADP-ribosyltransferases,22–24 although subsequent research has revealed that this is likely a minor activity catalyzed by only some sirtuins.6,7 These findings, along with the discoveries of new lysine acyl modifications, have sparked interest in other potential activities of sirtuins.

Recent studies have revealed that a subset of sirtuins can also catalyze depropionylation and debutyrylation in vitro and in vivo with varying catalytic efficiency.3,25 The sirtuin depropionylation reaction is similar to deacetylation, except that O-propionyl-ADP-ribose (OPADPR) is formed instead of OAADPR as a product.3,26 Modeling of sirtuins bound to propionyl- or butyryl-lysine suggested that the enzyme active site should be able to accommodate the propionyl group with minor rearrangements, but that binding of the bulkier butyryl modification would require more significant rearrangement to avoid steric clashes.3,25 Interestingly, the yeast sirtuin, Hst2, was shown to bind to both propionylated and butyrylated peptides with greater affinity than to an acetylated peptide.25,26 It remains unclear what governs the ability of a sirtuin to discriminate between acetyl-, propionyl-, and butyryl-lysine as substrates. Although the sirtuin catalytic domain is well conserved, substrate recognition and selectivity may be defined by minor differences in the sequence and configuration of the substrate-binding pocket, affecting the capacity of various sirtuins to accommodate larger acyl moieties. To gain insight into the basis for the various deacylation activities of sirtuins, we determined the crystal structure of a sirtuin from Thermotoga maritima, Sir2Tm, bound to a propionylated substrate and studied the binding of substrate and reaction kinetics of Sir2Tm depropionylation and deacetylation. These studies provide a structural and thermodynamic basis for the observed plasticity of the sirtuin active site and provide a model for understanding how other sirtuins catalyze removal of a variety of acyl modifications from lysine side chains.

Results

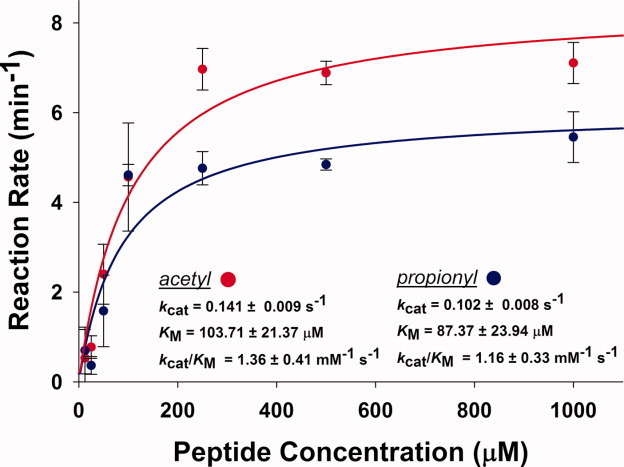

Sir2Tm depropionylates a propionylated p53 peptide

A previous study on sirtuin-mediated depropionylation reported that Sir2Tm can depropionylate propionyl-CoA synthetase from S. enterica in vitro.3 In this study, we tested the depropionylation activity of Sir2Tm on a peptide substrate derived from the C-terminus of the p53 tumor suppressor protein that has been used in previous structural studies of Sir2Tm.20,21,27 We confirmed that Sir2Tm can also efficiently depropionylate the p53 peptide with kinetics comparable to the deacetylation reaction (Fig. 2). The catalytic turnover rate (kcat) was 0.102 ± 0.008 s−1 for depropionylation and 0.141 ± 0.009 s−1 for deacetylation, indicating that depropionylation occurs at a comparable but slightly slower (1.38-fold lower) catalytic rate at saturating substrate conditions. We observed similar apparent KM values of 87.37 ± 23.94 μM and 103.71 ± 21.37 μM, for propionylated and acetylated p53 peptides, respectively. The resulting kcat/KM values for depropionylation and deacetylation are 1.16 ± 0.33 and 1.36 ± 0.41 mM−1 s−1, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Deacylation activity of Sir2Tm. Activity is shown for acetylated (red) and propionylated (blue) p53 peptides. Rates of reaction were measured by an NAD+ consumption assay.21 The reactions were performed with 50 μg/mL Sir2Tm and 1 mM NAD+ for 15 min at 37°C. Concentration of the substrate peptides was varied from 12.5 μM to 1 mM.

Sir2Tm binds to propionyl-lysine with higher affinity than acetyl-lysine

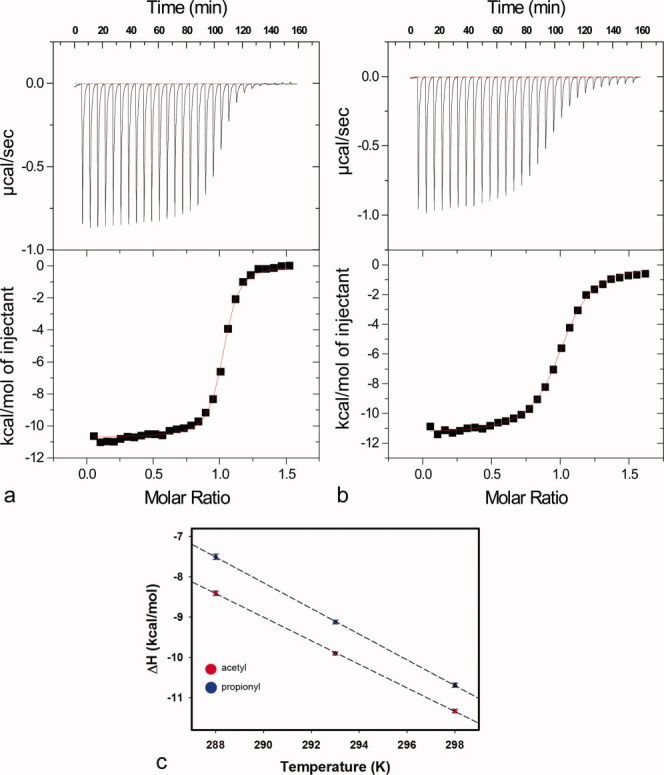

To assess how the kinetic constants for propionylated versus acetylated peptide substrates are related to substrate binding affinity, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to measure the thermodynamic parameters of Sir2Tm binding to both substrates. Binding experiments performed at 25°C showed that Sir2Tm binds the propionylated p53 peptide 4.4-fold more tightly, with a KD of 0.183 ± 0.017 μM when compared with 0.799 ± 0.038 μM for the acetylated form of the peptide [Fig. 3(a,b)]. This difference in binding affinity was unexpected given the similarity in KM values.

Figure 3.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of peptide binding. (a) Representative isothermal calorimetry titration of propionyl-lysine peptide binding to Sir2Tm at 25°C. Sir2Tm was titrated with injections of propionylated p53 peptide. (b) Representative isothermal calorimetry titration of acetyl-lysine peptide binding to Sir2Tm 25°C. (c) Change in heat capacity calculated based on temperature dependence of change in enthalpy of Sir2Tm binding to propionylated (blue) and acetylated (red) p53 peptides. The ΔCp values obtained for Sir2Tm binding were −318.8 ± 2.7 cal mol−1 K−1 for propionyl-lysine compared with −292.6 ± 3.8 cal mol−1 K−1 for acetyl-lysine.

We hypothesized that the tighter binding affinity of Sir2Tm to propionyl-lysine may be due to favorable interactions between the additional methylene group of propionyl-lysine with residues in the Sir2Tm. To further investigate the molecular basis for the observed difference in affinity, we analyzed the change in heat capacity (ΔCp) of Sir2Tm binding to both propionylated and acetylated p53 substrates. Measurement of ΔCp can reveal the contribution of polar and nonpolar interactions to binding, with a more negative ΔCp reflecting more hydrophobic interactions.28 ITC titrations were conducted at two additional temperatures (15 and 20°C) for both peptides (Table I). The ΔH values obtained for both substrates were plotted as a function of temperature to determine the slope [Fig. 3(c)], which gave ΔCp values for propionylated and acetylated substrates of −318.8 ± 2.7 and −292.6 ± 3.8 cal mol−1 K−1, respectively. The more negative ΔCp for the propionylated peptide as compared to the acetylated peptide indicates that the tighter binding of Sir2Tm to propionylated substrates versus acetylated substrates is likely due to the greater hydrophobicity of propionyl-lysine compared with acetyl-lysine.

Table I.

Summary of Sir2Tm Titrations with Propionylated and Acetylated p53 Peptides

| Temperature (°C) | KD (μM) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | ΔS (cal/mol K) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl | 15 | 0.667 ± 0.058 | −8.404 ± 0.0585 | −0.894 |

| Propionyl | 15 | 0.150 ± 0.027 | −7.502 ± 0.0640 | 5.249 |

| Acetyl | 20 | 0.711 ± 0.032 | −9.900 ± 0.0362 | −5.636 |

| Propionyl | 20 | 0.144 ± 0.015 | −9.119 ± 0.0515 | 0.220 |

| Acetyl | 25 | 0.799 ± 0.038 | −11.330 ± 0.0459 | −10.090 |

| Propionyl | 25 | 0.183 ± 0.017 | −10.690 ± 0.0520 | −4.998 |

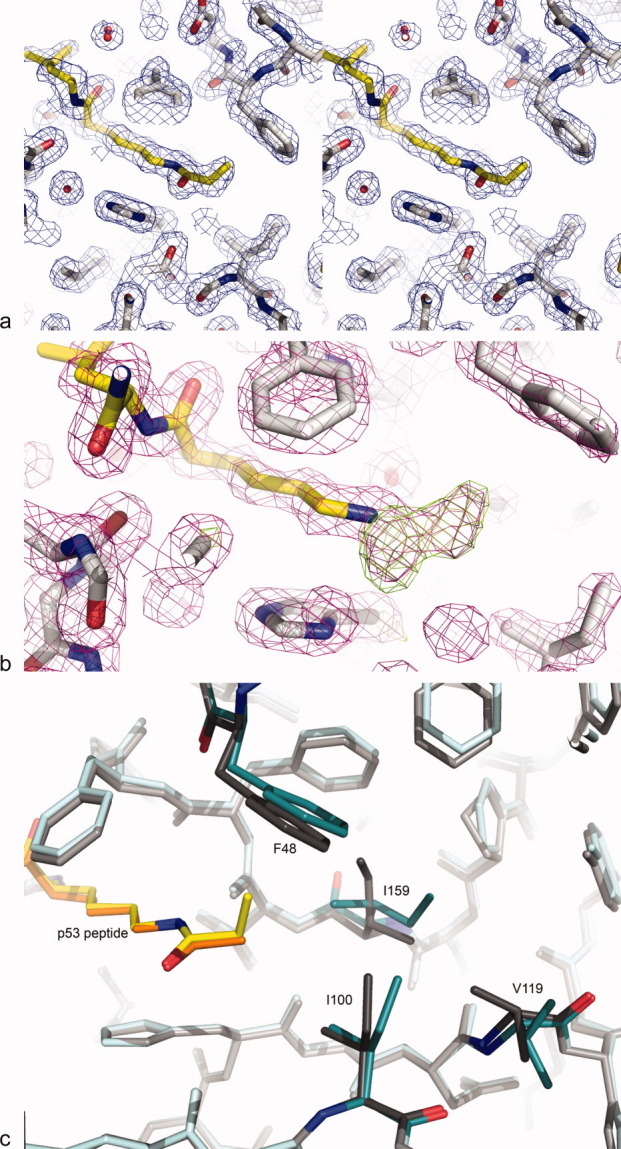

Structure of Sir2Tm bound to a propionylated p53 peptide

To understand the structural basis for the observed binding and kinetic constants for propionylated substrates, we determined the structure of Sir2Tm in complex with the propionylated p53 peptide at 1.8 Å resolution; crystallographic statistics are summarized in Table II. As expected, the overall structure is similar to the previously reported crystal structure of Sir2Tm bound to an acetylated p53 peptide,20 with all differences located in the enzyme active site [Fig. 4(a)]. Simulated annealing omit maps confirmed the presence and proper orientation of the propionyl moiety and the surrounding residues [Fig. 4(b)].

Table II.

Summary of Crystallographic and Refinement Statistics

| Diffraction data | |

|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell (Å) | 46.56, 60.01, 106.35 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.01–1.80 (1.83–1.80) |

| Measured reflections | 197,963 |

| Unique reflections | 28,346 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.82 (99.3) |

| Avg I/σ (merged data) | 23.8 (2.9) |

| Multiplicity | 7.0 (6.5) |

| Rmerge (%) | 9.9 (63.9) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Total atoms | 2,393 |

| Protein | 1,928 |

| Peptide | 117 |

| Zinc | 1 |

| Water | 247 |

| R factor (%) | 16.54 |

| Rfree (%) | 20.97 |

| RMSD | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.020 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.612 |

Values in parentheses correspond to highest resolution shell.

Figure 4.

Electron density maps showing region of peptide binding to Sir2Tm. (a) 2Fo-Fc stereo map (blue) contoured at 1σ of propionylated p53 peptide (yellow) bound to Sir2Tm (gray). (b) Simulated annealing omit map calculated with the propionyl moiety omitted. 2Fo-Fc map (purple) contoured at 1.5σ and Fo-Fc map (green) contoured at 3σ show well-defined positive density for the propionyl modification. (c) The positions of key Sir2Tm active site residues in complexes with propionylated (Sir2Tm teal, peptide yellow) and acetylated (Sir2Tm gray, peptide orange; PDB ID 2H2D) peptides.

The binding of propionyl-lysine to Sir2Tm gives rise to changes in the conformations of several residues in the Sir2Tm active site as compared to the acetyl-lysine bound structure [Fig. 4(c)]. Both acetyl- and propionyl-lysine fit into the active site of Sir2Tm in a hydrophobic pocket formed by residues F48, I100, and I159. However, rearrangements of these active site residues were critical to accommodate the bulkier propionyl group as compared to acetyl-lysine, and to form optimal interactions with the substrate [Fig. 4(c)]. In particular, I159 and F48 make the most extensive contacts with propionyl-lysine and differ the most in conformation from the acetyl-lysine bound structure.20 Isoleucine 159 adopts an alternative sidechain rotamer in the propionyl-lysine bound structure, resulting in an orientation of the short methyl arm of the isoleucine sidechain pointing toward the terminal methyl group of the propionyl moiety [Fig. 4(c)]. This rotation decreases the distance by 0.25 Å between this residue and the terminal methyl of propionyl-lysine as compared to the position of I159 in the acetyl-lysine bound structure. This results in more extensive van der Waals interactions between the propionyl group and the isoleucine side chain. The alternate rotamer of I159, in turn, creates room for the sidechain of I100 to shift away slightly from the propionyl-lysine, thereby eliminating steric clash between the propionyl group and active site residues. To accommodate the change in the orientation of I159, V119 also adopts a different rotamer, pointing away from the active site residues and thereby eliminating steric clashes with I159 [Fig. 4(c)]. Phenylalanine 48 also shifts its position in the Sir2Tm active site to accommodate the larger propionyl modification. In the structure of acetylated peptide bound to Sir2Tm, all phenyl ring carbons of Sir2Tm F48 are more than 4 Å away from the acetyl modification. However, binding to the propionyl moiety causes the phenyl ring of F48 to tilt by 10° (corresponding to a shift of approximately 0.78 Å between the Cζ carbons of the phenyl rings) to accommodate the terminal methyl of propionyl-lysine [Fig. 4(c)]. This shift also results in more favorable contacts between substrate and enzyme.

Discussion

The kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural studies presented here provide fresh insights into the depropionylation activity of sirtuins and how the enzyme active site can accommodate propionylated substrates, and potentially other, larger acyl modifications. The structure of Sir2Tm bound to a propionylated peptide shows that rearrangements of key residues in the active site both allow the enzyme active site to accommodate the bulkier propionyl-lysine modification and give rise to more extensive contacts with the propionyl group as compared to an acetyl group. These additional hydrophobic interactions account for the 4.4-fold lower KD observed for the propionylated peptide and the more negative ΔCp value for the propionylated substrate as compared to the acetylated substrate. A higher affinity for more hydrophobic acyl modifications has also been observed for the yeast sirtuin, Hst2,25 suggesting that this is likely a common property of many sirtuins.

Despite the 4.4-fold higher binding affinity for propionyl-lysine compared with acetyl-lysine, the kcat/KM value for depropionylation and deacetylation are comparable. A lower KD for Sir2Tm binding to propionyl-lysine would suggest an increase in kcat/KM, as this rate constant for sirtuin-mediated enzymatic reactions reflects the first steps in deacylation through nicotinamide cleavage.6,29–33 A number of reasons can account for this disparity. The additional methylene moiety of propionyl-lysine may enhance the affinity of Sir2Tm for this substrate at the expense of decreased catalysis. Smith et al.26 demonstrated that the nucleophilicity of the carbonyl oxygen of the propionyl moiety is decreased compared with the acetyl carbonyl oxygen, lowering the rate of sirtuin-mediated NAD+ cleavage for depropionylation compared with deacetylation.26 The discrepancy between KD and kcat/KM values may also be a result of nonproductive binding of propionyl-lysine in the Sir2Tm active site and would manifest itself as an increase in binding affinity without a concomitant increase in kcat/KM.34 It is possible that a nonproductive binding mode exists for propionyl-lysine binding, but that the subsequent binding of NAD+ induces productive binding.

The catalytic turnover rate, kcat, is determined by the rate-limiting step,35 which for sirtuin deacetylation is thought to be product release of deacetylated peptide or OAADPR, which are released in random order.32,33 The 1.38-fold difference observed in kcat between depropionylation and deacetylation is likely due to slower release of the OPADPR product than OAADPR because of tighter binding of the propionyl moiety to the Sir2Tm enzyme. Given that the propionyl group enhances the affinity of Sir2Tm for substrate, it is plausible that the affinity for propionylated product would also be enhanced.

The structure of Sir2Tm bound to a propionylated p53 peptide presented here shows how this enzyme accommodates the bulkier propionyl modification. Although some residues are shifted away from the modification in the active site to provide more space for the extra methylene in propionyl-lysine, some side chains are reoriented so that they make more favorable contacts with propionyl-lysine. In particular, the coupled change in rotamer of both I159 and V119 plays an essential role in accommodating the propionyl group and in forming favorable van der Waals interactions with the modification [Fig. 4(c)]. An additional shift of the F48 side chain also makes room for the larger modification. Although a previous study3 presented a model for how the propionyl group could be accommodated through relatively small shifts in Sir2Tm active site residues, our structural studies reveal that more significant rearrangements, in fact, take place. We also note that the propionyl group itself adopts a different rotamer in the crystal structure than that used in modeling studies,3 which could not have been anticipated from the molecular modeling. The propionyl rotamer observed in the crystal structure is more readily accommodated in the Sir2Tm active site.

The observed differences in the conformations of Sir2Tm residues in complexes containing acetylated versus propionylated peptide substrates offer insight into the differing depropionylation and debutyrylation activity observed among various sirtuin homologs.3,25 Although I159 is highly conserved and is either an isoleucine or valine, structural alignment of sirtuins shows that V119 is not conserved, with hydrophobic side chains such as leucine, methionine, or even phenylalanine replacing this residue. The ability of residues corresponding to I159 and V119 to adopt conformations that can accommodate different chemical groups will likely affect the depropionylation and debutyrylation activity of various sirtuins. As the rotamers of I159 and V119 are coupled during substrate binding, sequence variation at the residue analogous to V119 could govern the ability of sirtuins to bind to larger acyl modifications. Another key residue involved in substrate binding is F48 of Sir2Tm, which contacts the terminal methyl of the propionyl group and is found as either a phenylalanine or an alanine in other sirtuins. Sirtuins with an alanine in this position may be more likely to accommodate acyl modifications larger than acetylation, whereas a phenylalanine at this site may or may not affect binding, depending on the flexibility of this residue. At the same time, the central role of hydrophobic interactions in the binding of modified lysine residues suggests that the van der Waals interactions with F48 and I159 likely contribute favorably to peptide binding. Whether or not a given sirtuin can catalyze removal of modifications larger than an acetyl group likely depends on the fine balance between favorable hydrophobic interactions and unfavorable steric clashes in the active site in accommodating the modification.

Modeling studies of yeast sirtuin Hst2 binding to various acylated lysines by Smith et al.25 suggested that the residues analogous to F48, I100, and I159 of Sir2Tm (F67, I117, and I181 in Hst2) would require significant movement to accommodate butyryl-lysine in the active site with severe steric clash. Surprisingly, Hst2 binds more tightly to butyryl-lysine than to acetyl-lysine, although the debutyrylation activity was substantially lower than depropionylation activity.25 By analogy with our findings on Sir2Tm, it is possible that different rotamers of butyryl-lysine, as well as propionyl-lysine, could be accommodated in the Hst2 active site, perhaps facilitated by side chain rotamer shifts in the enzyme.

Although our results highlight the importance of enzyme active site and substrate conformations in governing whether or not a sirtuin is capable of depropionylation, the specificity of a given sirtuin for different peptide sequences may also play a role in regulating depropionylation activity, as is demonstrated in the case of human SIRT1. SIRT1 was initially reported to lack depropionylase activity based on an in vitro assay for depropionylation of S. enterica propionyl-CoA synthetase, whereas other sirtuins including Sir2Tm did demonstrate depropionylation activity with this substrate.3 However, subsequent studies demonstrated that SIRT1 depropionylates histone H3 peptides in vitro25 and p53 in vivo.4 This indicates that, although the SIRT1 active site is able to accommodate and bind propionyl-lysine, important determinants of substrate specificity depend on the amino acid sequence of the substrate itself, suggesting that residues outside the active site govern whether or not SIRT1 can bind to and deacylate a substrate. A previous study of an archaeal sirtuin, Sir2Af1, revealed that sirtuin affinity for its substrate could be altered by mutations to surface residues surrounding the active site.21 It is likely that, although the enzyme active site is adaptable enough to bind propionyl-lysine, SIRT1 surface residues govern whether or not the enzyme can make favorable contacts with the rest of the substrate as a means for providing substrate specificity.

Sirtuins are a remarkable example of active site plasticity, which allows members of this enzyme family to bind to different types of acyl substrates. Our study provides a first step in understanding the structural rearrangements in both the enzyme active site and the substrate that enable Sir2Tm to bind to both acetylated and propionylated substrates. These insights can provide a basis for modeling studies of sirtuins bound to different substrates and drugs that target members of this important class of enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

Sir2Tm was expressed in E. coli and purified as previously described.36 Purified Sir2Tm was dialyzed into 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 and concentrated to 16 mg/mL. The protein was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen in small aliquots and stored at −80°C until thawed for enzyme assays or crystallization.

Propionylated and acetylated p53 peptides (KKGQSTSRHKK(propionyl or acetyl)LMFKTEG) were commercially synthesized (CHI Scientific) and purified to greater than 95% purity by HPLC on a reverse phase C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm Venusil MP) with a 15–100% acetonitrile gradient developed over 25 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Stock peptide solution was made at 40 mM in deionized water neutralized with sodium hydroxide.

Enzymatic activity assays

Kinetics of Sir2Tm depropionylation and deacetylation were measured with a standard NAD+ consumption assay.21 Sir2Tm (50 μg/mL) was incubated with 1 mM NAD+ and acylated peptide substrates ranging in concentration from 12.5 μM to 1 mM for 15 min at 37°C. Under these conditions, steady-state initial velocities are maintained. Unconsumed NAD+ was quantified by enzymatic conversion of NAD+ to NADH, the latter of which can be measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 340 nM.21 NAD+ concentration measured this way is linear to at least 1 mM. The reaction progress at each timepoint was measured three times in independent experiments. The data were globally fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation [Eq. (1)] using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) to obtain the kinetic constants kcat and KM.

| (1) |

Kinetic values are reported as the mean and standard error of the fit parameters.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC experiments for Sir2Tm were performed as previously described,20 with minor modifications. Briefly, Sir2Tm was titrated with 458 μM propionylated or 380 μM acetylated p53 peptide. Peptides were titrated into buffer as controls to determine the heat of dilution. Each experiment included 25 injections of 7 μL of titrant peptide, spaced 330 s apart. The experiments were conducted at 15, 20, and 25°C. Peptide concentrations were accurately determined by amino acid analysis (Dana Farber Cancer Institute). Enzyme concentration was adjusted to obtain 1:1 stoichiometry of peptide binding to enzyme. This adjustment implied that the enzyme was approximately 75% active—although the enzyme concentration was measured at 85 μM by spectrophotometry, the concentration of active enzyme was 65 μM based on the 1:1 ratio. Data were analyzed with MicroCal Origin 5.0 software.

Crystallization

Sir2Tm was mixed with the propionylated p53 peptide to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL protein and 4 mM peptide and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The enzyme–substrate complex was set in crystallization drops at a 1:1 ratio with a well solution of 9.5% PEG3350 and 100 mM CHES, pH 8.5 at 20°C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals appeared after 1–2 days and were harvested after 5 days. For storage and data collection, crystals were briefly soaked in a cryoprotectant solution containing 10.5% PEG 3350, 100 mM CHES, pH 8.5, and 15% ethylene glycol and then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Crystallographic data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data were collected at 100 K at the BioCARS 14-BM-C beamline at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory using an ADSC Q315 detector. The data were indexed and scaled using HKL2000.37 The complex crystallized in the same space group and with similar cell dimensions as crystals of Sir2Tm bound to an acetylated p53 peptide. The structure was solved by molecular replacement with REFMAC5, using the coordinates of the Sir2Tm protein only from the structure of Sir2Tm bound to a peptide and NAD+ (PDB ID 2H4F and 2H2D).27 Subsequent building and refinements were performed with the graphics program COOT38 and REFMAC5 from the CCP4 suite.39

After the first few rounds of refinement, an unmodified version of the p53 peptide was built into the model. Positive density in both the 2Fo-Fc map contoured at 1σ and Fo-Fc map contoured at 3σ indicated that the propionyl modification was indeed present and well defined. After several rounds of refinement, the propionyl modification was introduced, followed by further rounds of refinement. Simulated annealing omit maps were calculated with the propionyl moiety of the p53 peptide omitted using CNS.41,42 The final structure contains residues 1–33 and 43–246 of Sir2Tm, 1 zinc atom, residues 2–14 of the peptide, and 247 water molecules. Refinement statistics are summarized in Table II.

Structure figures were created in Pymol.40

Coordinates have been deposited in the PDB with accession code 3PDH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Datta for advice and assistance and C. Berndsen for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science. 2002;298:2390–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Sprung R, Tang Y, Ball H, Sangras B, Kim SC, Falck JR, Peng J, Gu W, Zhao Y. Lysine propionylation and butyrylation are novel post-translational modifications in histones. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:812–819. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700021-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrity J, Gardner JG, Hawse W, Wolberger C, Escalante-Semerena JC. N-lysine propionylation controls the activity of propionyl-CoA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30239–30245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Z, Tang Y, Chen Y, Kim S, Liu H, Li SS, Gu W, Zhao Y. Molecular characterization of propionyllysines in non-histone proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:45–52. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800224-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanny JC, Moazed D. Coupling of histone deacetylation to NAD breakdown by the yeast silencing protein Sir2: evidence for acetyl transfer from substrate to an NAD breakdown product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:415–420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031563798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landry J, Sutton A, Tafrov ST, Heller RC, Stebbins J, Pillus L, Sternglanz R. The silencing protein SIR2 and its homologs are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5807–5811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110148297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Imai S, Chen D, Su F, Shiloh A, Guarente L, Gu W. Negative control of p53 by Sir2alpha promotes cell survival under stress. Cell. 2001;107:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Ng Eaton E, Imai SI, Frye RA, Pandita TK, Guarente L, Weinberg RA. hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell. 2001;107:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North BJ, Marshall BL, Borra MT, Denu JM, Verdin E. The human Sir2 ortholog, SIRT2, is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brachmann CB, Sherman JM, Devine SE, Cameron EE, Pillus L, Boeke JD. The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2888–2902. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottlieb S, Esposito RE. A new role for a yeast transcriptional silencer gene, SIR2, in regulation of recombination in ribosomal DNA. Cell. 1989;56:771–776. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90681-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JS, Boeke JD. An unusual form of transcriptional silencing in yeast ribosomal DNA. Genes Dev. 1997;11:241–254. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picard F, Kurtev M, Chung N, Topark-Ngarm A, Senawong T, Machado De Oliveira R, Leid M, McBurney MW, Guarente L. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2004;429:771–776. doi: 10.1038/nature02583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Min J, Landry J, Sternglanz R, Xu RM. Crystal structure of a SIR2 homolog-NAD complex. Cell. 2001;105:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin L, Wei W, Jiang Y, Peng H, Cai J, Mao C, Dai H, Choy W, Bemis JE, Jirousek MR, Milne JC, Westphal CH, Perni RB. Crystal structures of human SIRT3 displaying substrate-induced conformational changes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24394–24405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnin MS, Donigian JR, Pavletich NP. Structure of the histone deacetylase SIRT2. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:621–625. doi: 10.1038/89668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao K, Chai X, Marmorstein R. Structure of the yeast Hst2 protein deacetylase in ternary complex with 2′-O-acetyl ADP ribose and histone peptide. Structure. 2003;11:1403–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao K, Chai X, Marmorstein R. Structure and substrate binding properties of cobB, a Sir2 homolog protein deacetylase from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:731–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cosgrove MS, Bever K, Avalos JL, Muhammad S, Zhang X, Wolberger C. The structural basis of sirtuin substrate affinity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7511–7521. doi: 10.1021/bi0526332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avalos JL, Celic I, Muhammad S, Cosgrove MS, Boeke JD, Wolberger C. Structure of a Sir2 enzyme bound to an acetylated p53 peptide. Mol Cell. 2002;10:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frye RA. Characterization of five human cDNAs with homology to the yeast SIR2 gene: Sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) metabolize NAD and may have protein ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:273–279. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsang AW, Escalante-Semerena JC. CobB, a new member of the SIR2 family of eucaryotic regulatory proteins, is required to compensate for the lack of nicotinate mononucleotide: 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole phosphoribosyltransferase activity in cobT mutants during cobalamin biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31788–31794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanny JC, Dowd GJ, Huang J, Hilz H, Moazed D. An enzymatic activity in the yeast Sir2 protein that is essential for gene silencing. Cell. 1999;99:735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith BC, Denu JM. Acetyl-lysine analog peptides as mechanistic probes of protein deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37256–37265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith BC, Denu JM. Sir2 deacetylases exhibit nucleophilic participation of acetyl-lysine in NAD+ cleavage. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5802–5803. doi: 10.1021/ja070162w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoff KG, Avalos JL, Sens K, Wolberger C. Insights into the sirtuin mechanism from ternary complexes containing NAD+ and acetylated peptide. Structure. 2006;14:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabhu NV, Sharp KA. Heat capacity in proteins. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2005;56:521–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Northrop DB. On the Meaning of Km and V/K in Enzyme Kinetics. J Chem Educ. 1998;75:1153–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland WW. Partition analysis and the concept of net rate constants as tools in enzyme kinetics. Biochemistry. 1975;14:3220–3224. doi: 10.1021/bi00685a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson MD, Schmidt MT, Oppenheimer NJ, Denu JM. Mechanism of nicotinamide inhibition and transglycosidation by Sir2 histone/protein deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50985–50998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borra MT, Langer MR, Slama JT, Denu JM. Substrate specificity and kinetic mechanism of the Sir2 family of NAD+-dependent histone/protein deacetylases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9877–9887. doi: 10.1021/bi049592e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauve AA, Schramm VL. Sir2 regulation by nicotinamide results from switching between base exchange and deacetylation chemistry. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9249–9256. doi: 10.1021/bi034959l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science: a guide to enzyme catalysis and protein folding. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1999. p. xxi.p. 631. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cleland WW. What limits the rate of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction? Acc Chem Res. 1975;8:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith JS, Avalos J, Celic I, Muhammad S, Wolberger C, Boeke JD. Sir2 family of NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases. Methods Enzymol. 2002;353:282–300. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)53056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. Palo Alto, California: DeLano Scientific; 2008. Available at: http://www.pymol.org. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges N, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR System (CNS), A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR System. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]