Abstract

Objective

EphA2 overexpression predicts poor prognosis in endometrial cancer. To explore mechanisms for this association and assess its potential as therapeutic target, the relationship of EphA2 expression to markers of angiogenesis was examined using patient samples and an orthotopic mouse model of uterine cancer.

Results

Of 85 EE C samples, EphA2 was overexpressed in 47% of tumors and was significantly associated with high VEGF expression (p = 0.001) and high MVD counts (p = 0.02). High EphA2 expression, high VEGF expression and high MVD counts were significantly associated with shorter disease-specific survival. EA5 led to decrease in EphA2 expression and phosphorylation in vitro. In the murine model, while EA5 (33–88%) and docetaxel (23–55%) individually led to tumor inhibition over controls, combination therapy had the greatest efficacy (78–92%, p < 0.001). In treated tumors, combination therapy resulted in significant reduction in MVD counts, percent proliferation and apoptosis over controls.

Experimental Design

Expression of EphA2, estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), Ki-67, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and microvessel density (MVD) was evaluated using immunohistochemistry in 85 endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinomas (EEC) by two independent investigators. Results were correlated with clinicopathological characteristics. The effect of EphA2-agonist monoclonal antibody EA5, alone or in combination with docetaxel was studied in vitro and in vivo. Samples were analyzed for markers of angiogenesis, proliferation and apoptosis.

Conclusions

EphA2 overexpression is associated with markers of angiogenesis and is predictive of poor clinical outcome. EphA2 targeted therapy reduces angiogenesis and tumor growth in orthotopic uterine cancer models and should be considered for future clinical trials.

Key words: endometrial cancer, EphA2, VEGF, microvessel density, angiogenesis

Introduction

In 2009, there were an estimated 42,100 new cases of endometrial cancer diagnosed in the United States, making it the most common gynecologic malignancy.1 Most patients are diagnosed with early-stage disease and therefore have an excellent 5 year survival of approximately 85%.2 Unfortunately, for women with advanced or recurrent disease, treatment options are limited and an estimated 7,400 women succumbed to their disease in 2008.1,2 Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular pathways involved in endometrial carcinogenesis is required to develop novel and effective therapeutic strategies, especially for women with advanced or recurrent disease.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in biological therapies that target receptor tyrosine kinases with favorable responses reported in several clinical trials.3–5 The Eph receptors are the largest family of tyrosine kinases and are divided into two subclasses based on the interaction with their ligands, ephrin-A and ephrin-B.6 EphA2 was initially linked with neuronal migration during embryogenesis.7 However, there is growing evidence that high levels of EphA2 promote various aspects of malignant phenotype, including cell growth, migration, invasion, angiogenesis and survival of cancer cells.8–11 Furthermore, EphA2 is overexpressed in many human cancers, including breast, melanoma, prostate, lung and ovarian cancer.8,10–13 We have previously shown that EphA2 is overexpressed in over half of endometrial cancers and is associated with aggressive clinical features.14 More importantly, EphA2 overexpression is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with endometrial cancer.14 However, the molecular basis for this association is unknown. Based on the biological roles of EphA2 in promoting angiogenesis,15 we explored potential associations between EphA2 expression and markers of angiogenesis in patients with endometrial cancer. We also used an agonistic antibody, EA5 that binds to the extracellular domain of EphA2 and triggers receptor internalization and proteolysis.16 Using an orthotopic uterine cancer mouse model, we studied the effects of reduced EphA2 expression on tumor growth as well as effects on the local tumor microenvironment and markers of angiogenesis.

Results

Demographic factors.

The expression of EphA2, markers of angiogenesis and proliferation and steroid hormone receptors were evaluated in 85 endometrioid endometrial cancer specimens. The mean age of patients was 63.4 years (range, 39–91). Sixty-nine percent of patients had stage I or II disease. All tumors were of endometrioid histology. Distribution by grade was as follows: grade 1 (12%), grade 2 (73%) and grade 3 (15%). Seventy-three percent of the tumors were superficially invasive (<1/2 of the myometrial thickness). Thirty-six (42%) patients received adjuvant radiation and five (6%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Association between EphA2 and clinicopathologic features.

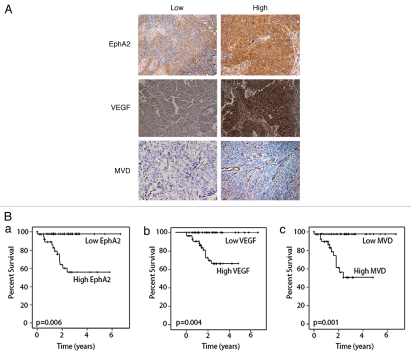

We evaluated all of the samples for EphA2 expression. Representative photomicrographs illustrating low and high expression of the study markers are presented in Figure 1A. EphA2 was overexpressed (high expression) in 47% of tumors, whereas the majority of the benign samples (90%) demonstrated low (negative or weak) expression of EphA2. EphA2 overexpression was associated with several aggressive features such as high stage disease (p = 0.001), high histologic grade (grade 3; p = 0.003) as well as increasing depth of myometrial invasion (p = 0.04; Table 1), but was not associated with the use of adjuvant radiation therapy. Since the presence of steroid hormone receptor expression is a good prognostic indicator in patients with endometrial cancer and may guide therapeutic strategies, we also evaluated the association of EphA2 with the expression of ER and PR in our cohort. High expression of ER and PR was detected in 40% and 50% of samples, respectively. EphA2 overexpression was demonstrated in 50% of tumors with low ER expression. Among tumors that showed low PR expression, high EphA2 expression was seen in 57% of cases (p = 0.016). Finally, we studied the relationship of EphA2 expression with the degree of cellular proliferation as represented by the percentage of tumor cells that stained positive for Ki-67. There was no significant difference in Ki-67 expression in our cohort.

Figure 1.

(A) Immunohistochemical expression of EphA2, VEGF and MVD in human endometrial cancer specimens. Semi-quantitative assessment of immunohistochemical expression was performed by assessing the percentage of stained tumor cells and staining intensity. Images were taken at original magnification x100. Tumor vessel density (MVD) was calculated as an average CD31-positive vessel count over three hot spots under x160 high power fields (HPF). The optimal, clinically relevant MVD cut-off point associated with death due to disease was calculated at 13.7 vessels/HPF. High MVD was >13.7/HPF and low MVD was ≤13.7/HPF. (B) Kaplan Meier Curves showing the effect of study markers on disease-specific survival in endometrial cancer. For statistical analyses, tumors were dichotomized into two groups based on the level of immunostaining as follows, for EphA2, low expression (negative, weak or moderate staining; SI = 0–8) and high expression (strong staining; SI = 9–12); for VEGF, low expression (negative or weak staining; SI = 0–4) and high expression (moderate and strong staining; SI = 5–12). High MVD was >13.7/HPF and low MVD was ≤13.7/HP F. p < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Table 1.

Association of EphA2 with clinicopathologic variables and markers of angiogenesis in endometrial cancer

| Variable (N = 85) | EphA2 expression | ||

| Low | High | p | |

| Stage* | |||

| Low (n = 59) | 38 | 21 | |

| High (n = 26) | 7 | 19 | 0.001 |

| Grade* | |||

| Low (1 or 2; n = 72) | 43 | 29 | |

| High (3; n = 13) | 2 | 11 | 0.003 |

| Depth of invasion* | |||

| ≤½ myometrium (n = 62) | 37 | 25 | |

| >½ myometrium (n = 23) | 8 | 15 | 0.04 |

| Adjuvant radiation | |||

| Received | 16 | 20 | |

| Not received | 29 | 20 | 0.2 |

| ER expression*# | |||

| Low (n = 48) | 24 | 24 | |

| High (n = 34) | 21 | 13 | 0.29 |

| PR expression*# | |||

| Low (n = 39) | 16 | 23 | |

| High (n = 43) | 29 | 14 | 0.016 |

| Ki-67 expression**# | |||

| Low (n = 55) | 33 | 22 | |

| High (n = 27) | 12 | 15 | 0.18 |

| VEGF expression*# | |||

| Low (n = 31) | 24 | 7 | |

| High (n = 54) | 21 | 33 | 0.001 |

| MVD | |||

| Low (<13.7/HPF) (n = 55) | 29 | 26 | |

| High (≥13.7/HPF) (N = 40) | 16 | 24 | 0.02 |

Note:

For the clinical variables, the groups are sub-classified as low and high as follows: Stage, low (I/II) and high (III/IV); FIGO grade, low (1 or 2) and high (3); Depth of invasion, low (≤½ myometrial thickness) and high (>½ myometrial thickness). Low expression of ER PR and VEGF denotes negative or weak expression; high expression of ER, PR and VEGF denotes strong expression.

Low expression of Ki-67 denotes ≤30% positive cells and high expression denotes >30% positive cells.

Missing numbers due to poor staining.

Clinical outcome based on EphA2 expression and angiogenic markers.

Prior to testing the prognostic significance of angiogenesis markers, we first performed univariate analyses of traditional clinical variables and EphA2 for DSS (Table 2). Representative Kaplan-Meier survival curves are illustrated in Figure 1B. Advanced age (cut-off 63.4 years) was significantly associated with an increased risk of death due to endometrial cancer (p = 0.02). As expected, high stage (p = 0.01), high tumor grade (p < 0.001) and increased depth of myometrial invasion (p = 0.003) were all associated with a shorter DSS. Among the immunohistochemical variables, EphA2 expression (p = 0.006, Fig. 1A) and Ki-67 (p = 0.057) predicted shorter DSS.

Table 2.

Univariate survival analysis of prognostic variables for DSS in endometrial cancer patients

| Variable | Mean Survival (y) | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Low | High | |||

| Age (cutoff at 63.4 y) | 4.97 | 4.64 | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.02 |

| High-stage* | 6.04 | 3.36 | 4.21 (1.41–12.59) | 0.01 |

| High FIGO grade* | 6.05 | 1.91 | 11.34 (3.85–33.44) | <0.001 |

| Depth of invasion >½* | 5.96 | 2.3 | 5.03 (1.74–14.59) | 0.003 |

| Low ER expression | 5.42 | 4.94 | 0.75 (0.23–2.44) | 0.63 |

| Low PR expression | 5.13 | 5.17 | 0.46 (0.14–1.49) | 0.18 |

| High Ki-67 expression | 6.01 | 4.02 | 2.89 (0.92–9.12) | 0.057 |

| High EphA2 expression | 6.52 | 3.86 | 17.03 (2.23–48.28) | 0.006 |

| High VEGF expression | NR | 3.64 | 18.01 (1.68–54.22) | 0.004 |

| MVD ≥13.7/HPF | 6.52 | 3.16 | 20.33 (2.64–96.32) | 0.001 |

For the clinical variables, the groups are sub-classified as low and high as follows: Stage, low (I/II) and high (III/IV); FIGO grade, low (1 or 2) and high (3); Depth of invasion, low (≤½ myometrial thickness) and high (>½ myometrial thickness). The same criteria for low and high expression of immunohistochemical variables were used as in Table 1. NR, not reached.

Based on the functional role of EphA2 in tumor angiogenesis, we next examined the clinical significance of two markers of angiogenesis (microvessel density and VEGF expression) and also their relationship to EphA2 levels. Low VEGF expression was present in 36% of samples, whereas 63% had high positivity. The presence of high VEGF expression was significantly associated with high stage (p = 0.03), high grade (p = 0.02) high MVD counts (p = 0.001), as well as low expression of ER (p = 0.04), but not with depth of myometrial invasion, Ki-67 or PR expression (p = 0.06) (Table 3). Furthermore, the median DSS was also significantly lower in patients whose tumors overexpressed VEGF (DSS: 3.64 years) compared to those with low VEGF expression (DSS: not reached; p = 0.004; Fig. 1B).

The median MVD was 15.4 vessels/HPF (range, 4.2–46.7). MVD >13.7 vessels/HPF, the cut-off associated with the greatest hazard for death, was associated with high grade (p = 0.019), low PR expression (p = 0.008) and high VEGF expression (p = 0.001). There was a trend towards an association between high MVD and high stage (p = 0.07), however the associations between MVD and depth of invasion, ER and Ki-67 expression were not statistically significant (Table 3). The mean DSS for patients with tumors with an MVD above the cutoff >13.7/HPF was 3.16 years compared to those with a cut-off <13.7/HPF (DSS: 6.52 years; p = 0.001; Fig. 1B).

Table 3.

Association of angiogenic markers (VEGF and MVD) with clinicopathologic variables in endometrial cancer

| Variable (N = 85) | VEGF expression | MVD counts/HPF | ||||

| Low | High | p | <13.7 | ≥13.7 | p | |

| Stage | ||||||

| Low (n = 59) | 26 | 33 | 35 | 24 | ||

| High (n = 26) | 5 | 21 | 0.026 | 10 | 16 | 0.07 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Low (1 or 2; n = 72) | 30 | 42 | 42 | 30 | ||

| High (3; n = 13) | 1 | 12 | 0.019 | 3 | 10 | 0.019 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| ≤½ myometrium (n = 62) | 24 | 38 | 33 | 29 | ||

| >½ myometrium (n = 23) | 7 | 16 | 0.48 | 12 | 11 | 0.93 |

| ER expression*# | ||||||

| Low (n = 49) | 14 | 35 | 25 | 24 | ||

| High (n = 33) | 17 | 16 | 0.036 | 20 | 13 | 0.39 |

| PR expression*# | ||||||

| Low (n = 40) | 11 | 29 | 16 | 24 | ||

| High (n = 42) | 20 | 22 | 0.06 | 29 | 13 | 0.008 |

| Ki-67 expression**# | ||||||

| Low (n = 55) | 23 | 32 | 32 | 23 | ||

| High (n = 27) | 8 | 19 | 0.28 | 13 | 14 | 0.39 |

| MVD | ||||||

| Low (<13.7/HPF) (n = 45) | 24 | 21 | ||||

| High (≥13.7/HP F) (N = 40) | 7 | 33 | 0.001 | |||

Note:

Low expression of ER, PR and VEGF denotes negative or weak expression; high expression of ER, PR and VEGF denotes strong expression.

Low expression of Ki-67 denotes ≤30% positive cells and high expression denotes >30% positive cells.

Missing numbers due to poor staining.

We next asked whether EphA2 was related to VEGF expression and microvessel density. EphA2 overexpression was detected in 61% of tumors with high VEGF expression compared to 22% with low VEGF expression (p = 0.001). EphA2 overexpression was also associated with higher MVD counts, with 57% of tumors overexpressing EphA2 demonstrating MVD greater than the cut-off limit. In comparison, low EphA2 expression was associated with 35% of tumors with high MVD counts (p = 0.02). These findings suggest that EphA2 could play a role in endometrial cancer angiogenesis.

In vitro and in vivo effects of EpA2-targeting by an agonist antibody.

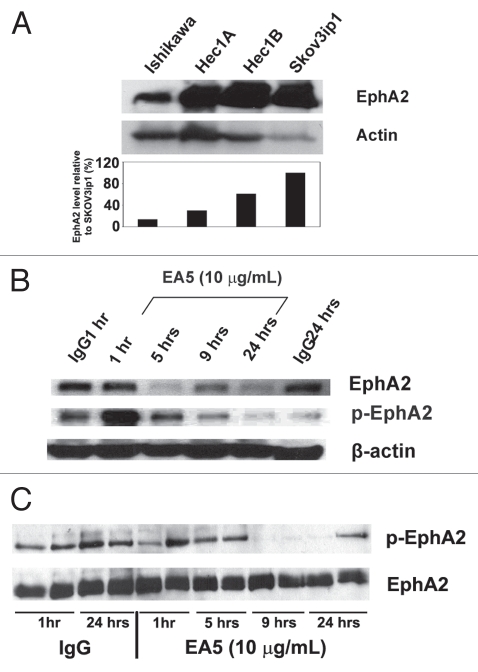

On the basis of our clinical observations, we next asked whether EphA2 downregulation would decrease angiogenesis and reduce in vivo tumor growth. We confirmed that EphA2 expression was present in several endometrial cancer cell lines: Hec1A, Hec1B and Ishikawa (Fig. 2A). Prior to performing in vivo therapy experiments, we tested the effects of EA5 on Hec1A and Ishikawa endometrial cancer cells by treating with EA5 for various time points and total EphA2 and phosphorylated EphA2 expression were examined. In the Hec1A cell line, EphA2 expression began to decrease as early as 5 hours after treatment and was sustained for up to 24 hours. EA5 treatment led to rapid phosphorylation (1 hour after treatment) that rapidly dissipated 5 hours after treatment. Treatment with a control antibody had no effect on EphA2 expression; however, minimal phosphorylation was observed at 1 hour after treatment (Fig. 2B). In Ishikawa cells, total EphA2 was not affected by EA5 treatment (Fig. 2C). Compared to the Hec1A cell line, Ishikawa cells appear to have greater baseline phosphorylated EphA2 as noted in control IgG lanes; however, phosphorylation rapidly decreased with EA5 treatment and remained decreased up to 24 hours following treatment.

Figure 2.

Expression and modulation of EphA2 in endometrial cancer cell line. (A) EphA2 expression in endometrial cancer cell lines (Hec1A, Hec1B and Ishikawa) was determined by western blot. The ovarian cancer cell line, SKOV3ip1, was used as a positive control. Densitometry analysis (graph below) represents percent (%) total EphA2 expression compared to SKOV3ip1 cells. Hec1A (B) and Ishikawa (C) endometrial cancer cells were exposed to 10 µg/mL of EA5 or to isotype control IgG for varying times and separate cell lysate samples were analyzed for total EphA2 by immunoblotting or phosphorylated EphA2 by immunoprecipitation with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody followed by immunoblotting for total EphA2.

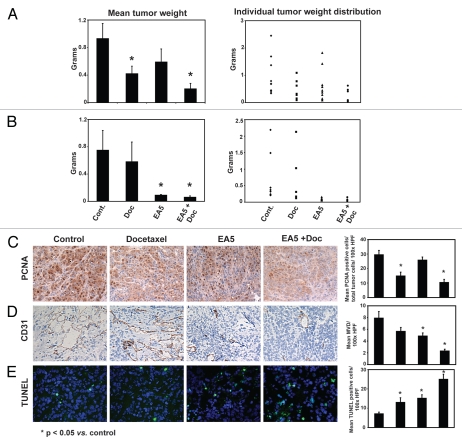

To examine the therapeutic potential of anti-EphA2 therapy, we examined the antitumor effects of EA5 in the Hec1A and Ishikawa models. Compared to mice treated with the control antibody, docetaxel alone reduced tumor growth by 55% (Hec1A; p = 0.02; Fig. 3A) and 23% (Ishikawa: p = 0.14; Fig. 3B). EA5 treatment also resulted in noticeable antitumor activity in the Hec1A model (37% reduction of tumor weight vs. controls; p = 0.10; Fig. 3A) and even more significantly in the Ishikawa model (88% reduction; p = 0.003; Fig. 3B). The greatest reduction in tumor growth compared to control mice was observed with EA5 and docetaxel combination treatment in the Hec1A (78% reduction; p = 0.003; Fig. 3A) and Ishikawa (92%; p = 0.004; Fig. 3B) models. To determine whether the addition of docetaxel provided additional benefit to mice treated with EA5, comparison was performed between these two respective groups. In the Ishikawa model, the average tumor weight was less with combination therapy versus single agent EA5 treatment; however, this difference was not significantly significant (p = 0.1). In the Hec1A model, combination therapy led to significant increased antitumor activity over EA5 therapy alone (p = 0.03). No obvious toxicities were observed in the animals during therapy experiments as assessed by mouse weights, behavioral changes, feeding habits and mobility.

Figure 3.

Effect of EphA2-targeted therapy in vivo. Mice injected with Hec1A (A) and Ishikawa (B) cells were treated with control IgG antibody (R347), R347 + docetaxel (Doc), EphA2 antibody (EA5), or the combination of docetaxel and EA5 (EA5 + Doc). After 5–6 weeks of treatment, after mean tumor weights (left graphs) and distributions (right graphs) were recorded. Hec1A tumors collected at the conclusion of therapy experiments were stained for (C) PCNA, (D) CD31 and (E) TUNEL. Representative sections (final magnification, x100) are shown. A graphic representation of the mean percent PCNA-positive cells, average number of CD31-positive cells and TUNEL-positive cells are shown in the adjoining graphs. *p < 0.05 compared to controls. Bars in graphs represent SEM.

Effects of anti-EphA2 activity on the tumor microenvironment.

To determine the potential mechanisms by which inhibition of EphA2 activity resulted in antitumor activity, we examined tumors from the Ishikawa and Hec1A therapy models for markers of tumor cell proliferation (PCNA), angiogenesis (CD31) and apoptosis (TUNEL; Hec1A model only). Compared to tumors from control mice, tumor cell proliferation was reduced with docetaxel in both the Ishikawa (21% reduction; p = 0.03) and Hec1A models (50% reduction; p < 0.01). Single agent therapy with EA5 was superior in reducing proliferation, compared to tumors from control mice, in the Ishikawa (24%; p < 0.01) compared to Hec1A tumors (13%; p = 0.32; Fig. 3C). Combination therapy was significantly superior to either single agent in both models (35–65%; p < 0.001 for both models). Tumor vascularity was significantly reduced by EA5-treated regimens in both Ishikawa and Hec1A models (EA5: 36–39% reduction vs. controls, p < 0.05 and EA5 + docetaxel: 59–72%, p < 0.001; Fig. 3D). The effects of docetaxel monotherapy were similar in the Ishikawa model (29% reduction vs. controls, p = 0.01) when compared to the Hec1A model (28% reduction, p = 0.09); not statistically different in the latter. Even when compared to both single agent therapies, combination therapy led to a significant reduction in angiogenesis in both models (p < 0.01). This trend continued in the TUNEL analyses of Hec1A tumors with combination therapy significantly increasing tumor cell apoptosis compared to all other three treatment arms (p < 0.01; Fig. 3E).

Discussion

The key findings of this study are that overexpression of EphA2 in endometrial carcinoma is associated with increased expression of angiogenic markers including microvessel density and VEGF. Moreover, these angiogenic markers are associated with aggressive phenotypic features including high-stage, high-grade and low steroid receptor status. Significantly, both high MVD counts and VEGF overexpression are important predictors of shorter disease-specific survival in these patients. We also found that the use of an agonistic antibody that leads to reduction in EphA2 activity, when combined with docetaxel, results in significant tumor growth inhibition in an orthotopic uterine cancer model. These effects appear to be due, in part, to decreased microvessel density in treated tumors as well as decreased tumor cell proliferation and increased apoptosis. These results indicate that EphA2 may be an attractive anti-vascular therapeutic target for patients with endometrial cancer.

The Eph (erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma cell line) family of receptor tyrosine kinases was initially described by Hirai and colleagues20 in 1987 and has been implicated in several critical roles in signal transduction in both normal physiology as well as tumorigenesis.9,10,21 Importantly, there are reports that implicate ephrin signaling in abnormal vascular development including tumor angiogenesis.22 EphA2 overexpression has been reported in several solid tumors including breast, prostate, non-small cell lung (NSCLC) and ovarian cancers.12–14 In malignant cells, EphA2 remains unphosphorylated and accumulates on the cell surface.23 Kinch and colleagues demonstrated that EphA2-transfected non-transformed cells show increased growth in vitro and form larger and more aggressive tumors in vivo.11 Our group has recently published findings from 139 patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer which showed that EphA2 overexpression is an independent prognostic factor for survival in this group of patients,14 with over half of the tumors overexpressing this oncoprotein. In the present study, a sub-group of these patients was evaluated to investigate a possible angiogenic basis for the poor clinical outcome associated with EphA2 overexpression. In this cohort, EphA2 overexpression remained a strong predictor of poor outcome. Tumors with EphA2 overexpression were significantly associated with high levels of angiogenesis markers, specifically VEGF expression and MVD counts. Tumor cells that overexpress EphA2 are involved in vascular mimicry and form vasculogenic-like networks in vitro, thus affecting tumor cell plasticity.24 Similar findings have been reported by Kataoka and colleagues where EphA2 overexpression was associated with high microvessel counts in human colorectal cancers.25 While there has been a recent study that supports the role of EphA2 in ovarian cancer15 and colorectal cancer25 angiogenesis, this is the first study that links EphA2 with angiogenesis in endometrial cancer. Recently, overexpression of EphA2 in endothelial cells was found to be associated with elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9).15 It is well known that both MMP-2 and MMP-9 degrade type IV collagen, a major component of the basement membrane and are associated with active neovascularization.26 In our study, EphA2 overexpression was seen in tumors that demonstrated higher levels of proliferation by Ki-67 staining. These findings are supported by other studies, which indicate that EphA2 is involved in tumor cell growth, angiogenesis and differentiation.17,18

On the basis of the suspected biological roles of EphA2 and its correlations with angiogenesis in clinical samples, we examined the therapeutic potential of utilizing an EphA2 agonistic antibody, EA5, in orthotopic uterine cancer models. We found that EA5 in combination with cytotoxic therapy could significantly reduce the growth of endometrial tumors, consistent with recent reports with EphA2-targeted therapy in breast and ovarian cancer models.16,18 While docetaxel was examined in the current experiments, other agents have been tested demonstrating similar activity in patients. Compared to other taxanes, such as paclitaxel, docetaxel is known to have non-overlapping activity and appears to be more potent.27 Nevertheless, evaluation of other compounds such as anthracyclines and platinum may also be warranted in future studies. Interestingly, we observed that the effects on tumor growth inhibition of single agent therapy with EA5 were more pronounced in the Ishikawa model compared to Hec1A. In vitro, EphA2 phosphorylation decreased following treatment in both models; however, total EphA2 appeared more stable in the Ishikawa cells. Although the underlying reason behind this observation is not fully clear at this time, these findings may be one possible explanation for the differences observed between these two models. Similar to previous studies, the antitumor effects of EphA2 inhibition are more likely secondary to modulation of one or more critical pathways within the tumor microenvironment. The tumors from mice treated with either single agent EA5, docetaxel or combination EA5 + docetaxel were examined for effects on tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis and apoptosis. Interestingly, both EA5 treatment arms showed significant decreases in microvessel density. Further supporting the role of EphA2 in angiogenesis is a study by Cheng and co-workers, where treatment of transgenic mice with soluble EphA receptors resulted in enhanced endothelial cell apoptosis in an orthotopic pancreatic cancer model.28 Additionally, systemic treatment targeted against EphA2 successfully inhibited VEGF-induced angiogenesis.28 In an ovarian cancer model, treatment with EA5 resulted in reduced microvessel density, reduced VEGF protein and mRNA levels and a resultant increase in endothelial cell apoptosis.18 Another novel approach for targeting EphA2 using intraperitoneal liposomal EphA2-siRNA complexes along with paclitaxel has been used in an orthotopic ovarian cancer model.29 This treatment regimen resulted in reduction in tumor growth compared to non-silencing siRNA and paclitaxel treatment.29 Therefore, it appears that there are several approaches by which effective downregulation of EphA2 is feasible. Developing treatment strategies that target EphA2 could provide novel alternative options for patients with endometrial cancer.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge this is the first study to investigate the clinical and biological correlates between EphA2 expression and angiogenesis in endometrial cancer. These results indicate that EphA2 is a viable target, alone or in conjunction with cytotoxic chemotherapy, for the treatment of patients with advanced endometrial cancer.

Materials and Methods

Samples for immunostaining.

Following IRB approval, archived formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples were obtained from 85 patients with endometrioid endometrial carcinoma who were surgically treated at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center between 2000 and 2004. Patients were surgically staged based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system. None of the patients received pre-operative chemotherapy or radiation. Endometrial samples from ten women who underwent hysterectomy for benign causes were included as controls for the expression of the study proteins.

Immunohistochemical staining.

The methods for immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded and frozen samples samples have been described previously.15,17,18 Samples were sectioned at 4 µm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for tumor confirmation. Sections adjacent to the H&E staining were used for immunohistochemical staining. Primary antibody used for human samples included: monoclonal EphA2 antibody (dilution 1:50, MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD), mouse antihuman estrogen receptor (ER; dilution 1:10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) mouse antihuman progesterone receptor (PR; dilution 1:75, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); mouse antihuman Ki-67 (dilution 1:100; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGF (dilution 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and mouse antihuman CD31 monoclonal antibody (dilution 1:20, Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Orthotopic sample primary antibodies included: rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD31 (1:800; BD Bioscience, Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and PC-10 mouse monoclonal IgG PCNA (1:50; Dako, Carpinteria, CA). TUNEL staining was performed as described previously.18

Semiquantitative analysis of immunostaining.

All human samples were reviewed by two investigators including a gynecologic pathologist (D.C.), who were blinded to the clinical outcome of patients. Semi-quantitative assessment of immunohistochemical expression was performed as described previously.13,15,17,19 Briefly, the percentage of positively stained cells was rated as: 0 points, 0–5%; 2 points, 6–50%; 3 points, >50%. The staining intensity was graded as follows: 1 point, weak intensity; 2 points, moderate intensity; 3 points, strong intensity. Points for the intensity and percentage of positive cells were combined and an overall score index (SI 0–3) was assigned. Tumors were categorized into four groups based on the SI: negative expression SI, 0 or <5% cells stained regardless of intensity; weak expression (SI, 1) 1 to 2 points; moderate expression (SI, 2) 3 to 4 points; strong expression (SI, 3) 5 to 6 points. For statistical analysis, the patients were dichotomized into two groups: low expression (SI, 0 or 1) included those with negative or weak expression and high expression (SI, 2 or 3) included those with moderate or strong expression. For Ki-67 and PCNA analyses, the number of positively stained cells in 5-high powered fields in the areas of greatest proliferation was calculated and the percentage of positive cells per field was calculated. Tumor vessel density (MVD) was calculated as an average CD31-positive vessel count over three hot spots under x160 high power fields (HPF). A vessel was defined as an open lumen lined by one or more CD31-positive cells. For tumor cell apoptosis analysis, the average number of TUNEL positive cells was calculated as an average over 5-high powered fields. For animal experiments, the average number of PCNA, CD31 and TUNEL was calculated similarly as for the human samples except slides of tumor from three different mice for each treatment group was performed.

For statistical analyses of human samples, tumors were dichotomized into two groups based on the level of immunostaining as outlined above. For EphA2, ER, PR and VEGF, low expression and high expression; for Ki-67, low expression (Ki-67 positive cells ≤30%) and high expression (Ki-67 positive cells >30%). A receiver operator characteristic curve anaylsis in previous analyses was used to determine the optimal cut-off point associated with death due to disease.19 Based on these results, MVD was dichotomized at 13.7 vessels/HPF (p = 0.05). For all immunohistochemical analyses, the independent scores from both investigators were consolidated into a final score, which is reported in this study. Any differences in the scores were adjudicated following discussion between the two investigators.

Clinicopathologic analysis.

All patients underwent surgical exploration and primary surgical staging as the initial treatment. The pathologic diagnosis was verified from the pathology reports. A gynecologic pathologist (D.C.) reviewed all the H&E slides to confirm the histopathologic diagnosis and tumor grading. Based on FIGO stage, patients were divided into two groups, low stage (FIGO stage I and II, n = 59) and high stage (FIGO stage III and IV, n = 26). The treating gynecologic oncologist determined the adjuvant therapy. A clinical remission was defined as no evidence of disease based on physical examination and/or imaging studies. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was defined as the time from treatment completion until the date of death or the date of last contact.

Western blot/immunoprecipitation analyses of EphA2 in vitro.

EphA2 expression in endometrioid endometrial cells lines (Hec1A, Hec1B and Ishikawa) was determined by western blot. The ovarian cancer cell line, SKOV3ip1, was used as a positive control.18 Cell lysates were obtained with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton, 0.5% deoxycholate, 25 µg/mL leupeptin, 10 µg/mL aprotinin, 2 mM EDTA and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate), centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C followed by determination of protein concentration with Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Following protein loading (50 µg/well), bands were separated on a 10% gel by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose paper, blocked with 5% milk for 2 hours at room temperature (RT) and, incubated with either a mouse anti-human/mouse EphA2 antibody (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (GE Healthcare UK Limited, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 2 hours at RT. Blots were developed with the ECL western Blotting Detection Kit (GE Healthcare). Actin was used for loading control and all experiments were repeated in duplicate. For immunoprecipitation assays, protein (500 µg) was incubated with an EphA2 antibody for 12 hours at 4°C. Protein A sepharose beads (60 µL of a 1:1 dilution in PBS; Upstate Cell Signaling, Lake Placid, NY) were then added and the mixture was incubated for 4 hours at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm at 4°C for 1 min, washed with PBS and resuspended in equal amount of PBS/Laemmli buffer. Western blot assay for phosporylated EphA2 (anti-pY; Upstate) expression was then performed as described above.

EphA2 targeted therapy in vivo.

Female athymic nude mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute-Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, MD) and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions. They were cared for in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the American Association for Accreditation for Laboratory Animal Care and the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all studies were approved and supervised by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The two endometrial cancer cell lines, Hec1A and Ishikawa, were maintained and prepared for in vivo injection as previously described.19 The mice were inoculated with cells by intrauterine injection, as previously described by our group.19

For therapy experiments, mice were randomized into four treatment groups: (a) control IgG antibody (R347; MedImmune; Gaithersburg, MD) 10 µg/g in 200 µl (intraperitoneal [i.p.], twice weekly); (b) R347 + docetaxel 50 µg in 200 µl PBS (i.p., weekly); (c) EphA2 antibody (EA5; MedImmune) 10 µg/g in 200 µl PBS (i.p., twice weekly); (d) docetaxel and EA5 (both drugs given at doses and frequency described above for each drug alone). Therapy was initiated two weeks following cell line injection. Mice were monitored for adverse effects and sacrificed by cervical dislocation 6–7 weeks following initiation of treatment. At the completion of each experiment, mouse weights, tumor weights, tumor location and number of tumor nodules were recorded for each treatment group. Tumor specimens were processed for further analysis by preservation in optimum cutting temperature (OCT; Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN) medium (for frozen slides) as well as fixed in formalin (for paraffin slides). Statistical analyses of outcome variables (tumor weights, tumor nodules and mouse weights) were compared among treatment groups with the Mann-Whitney U test. All tests were two-sided and a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis.

In patient samples, Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used, as appropriate, to test for the association in the proportions across levels of a single covariate factor and expression of EphA2, ER, PR, Ki-67, VEGF and MVD counts. Patients who were alive at last follow-up or died from causes other than uterine cancer were censored at the date of last follow-up. Disease specific survival (DSS) estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit method. A two-sided log-rank test was used to test for differences between survival curves. DSS was assessed using univariate survival analysis. For in vivo therapy experiments, 10 mice were used in each group, which provided the power to detect 50% reduction in tumor size (β error 0.2). Continuous variables were compared using Student's t test (2 groups) or ANOVA (all groups) if normally distributed. For non-parametric distribution, Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests (all groups) was used. A value of p < 0.05 on two-tailed testing was deemed statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

A.A.K. was supported by the Betty Ann Asche-Murray Fellowship Award; W.M.M., Y.G.L., W.A.S., A.M.N., R.L.S. were supported by the National Cancer Institute (T32 Training Grant CA101642). Portions of this work were supported by the NIH (P50 CA098258, P50 CA083639, CA128797, RC2GM092599, U54 CA151668) and the Betty Ann Asche Murray Distinguished Professorship to A.K.S.

Abbreviations

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PR

progesterone receptor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- EA5

EphA2 agonist monoclonal antibody

- EEC

endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma

- MVD

microvessel density

- HPF

high power field

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- DSS

disease specific survival

- RT

room temperature

- MMT

matrix metalloproteinase

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose PG. Endometrial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:640–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608293350907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caponigro F, Formato R, Caraglia M, Normanno N, Iaffaioli RV. Monoclonal antibodies targeting epidermal growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor with a focus on head and neck tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:212–217. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000159623.68506.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripathy D, Slamon DJ, Cobleigh M, Arnold A, Saleh M, Mortimer JE, et al. Safety of treatment of metastatic breast cancer with trastuzumab beyond disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1063–1070. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale NW, Holland SJ, Valenzuela DM, Flenniken A, Pan L, Ryan TE, et al. Eph receptors and ligands comprise two major specificity subclasses and are reciprocally compartmentalized during embryogenesis. Neuron. 1996;17:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flanagan JG, Vanderhaeghen P. The ephrins and Eph receptors in neural development. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andres AC, Reid HH, Zurcher G, Blaschke RJ, Albrecht D, Ziemiecki A. Expression of two novel eph-related receptor protein tyrosine kinases in mammary gland development and carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 1994;9:1461–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:462–475. doi: 10.1038/nrm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker-Daniels J, Coffman K, Azimi M, Rhim JS, Bostwick DG, Snyder P, et al. Overexpression of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase in prostate cancer. Prostate. 1999;41:275–280. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19991201)41:4<275::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelinski DP, Zantek ND, Stewart JC, Irizarry AR, Kinch MS. EphA2 overexpression causes tumorigenesis of mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2301–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinch MS, Moore MB, Harpole DH., Jr Predictive value of the EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase in lung cancer recurrence and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:613–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thaker PH, Deavers M, Celestino J, Thornton A, Fletcher MS, Landen CN, et al. EphA2 expression is associated with aggressive features in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5145–5150. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamat AA, Coffey D, Merritt WM, Nugent E, Urbauer D, Lin YG, et al. EphA2 overexpression is associated with lack of hormone receptor expression and poor outcome in endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:2684–2692. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin YG, Han LY, Kamat AA, Merritt WM, Landen CN, Deavers MT, et al. EphA2 overexpression is associated with angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:332–340. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carles-Kinch K, Kilpatrick KE, Stewart JC, Kinch MS. Antibody targeting of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase inhibits malignant cell behavior. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2840–2847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamat AA, Fletcher M, Gruman LM, Mueller P, Lopez A, Landen CN, Jr, et al. The clinical relevance of stromal matrix metalloproteinase expression in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1707–1714. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landen CN, Jr, Lu C, Han LY, Coffman KT, Bruckheimer E, Halder J, et al. Efficacy and antivascular effects of EphA2 reduction with an agonistic antibody in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1558–1570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamat AA, Merritt WM, Coffey D, Lin YG, Patel PR, Broaddus R, et al. Clinical and biological significance of vascular endothelial growth factor in endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7487–7495. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirai H, Maru Y, Hagiwara K, Nishida J, Takaku F. A novel putative tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the eph gene. Science. 1987;238:1717–1720. doi: 10.1126/science.2825356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamoto M, Bergemann AD. Diverse roles for the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases in carcinogenesis. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:58–67. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brantley DM, Cheng N, Thompson EJ, Lin Q, Brekken RA, Thorpe PE, et al. Soluble Eph A receptors inhibit tumor angiogenesis and progression in vivo. Oncogene. 2002;21:7011–7026. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker-Daniels J, Hess AR, Hendrix MJ, Kinch MS. Differential regulation of EphA2 in normal and malignant cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Hess AR, Seftor RE. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kataoka H, Igarashi H, Kanamori M, Ihara M, Wang JD, Wang YJ, et al. Correlation of EPHA2 overexpression with high microvessel count in human primary colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liotta LA, Steeg PS, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Cancer metastasis and angiogenesis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cell. 1991;64:327–336. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90642-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsumata N. Docetaxel: an alternative taxane in ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:9–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng N, Brantley D, Fang WB, Liu H, Fanslow W, Cerretti DP, et al. Inhibition of VEGF-dependent multistage carcinogenesis by soluble EphA receptors. Neoplasia. 2003;5:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landen CN, Merritt WM, Mangala LS, Sanguino AM, Bucana C, Lu C, et al. Intraperitoneal delivery of liposomal siRNA for therapy of advanced ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1708–1713. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]