Abstract

Epilepsy is a common, chronic neurological disorder. It is characterized by recurring seizures which are the result of abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Molecular pathways underlying neuronal death are of importance because prolonged seizure episodes (status epilepticus) cause significant damage to the brain, particularly within vulnerable structures such as the hippocampus. Additionally, repeated seizures over time in patients with poorly controlled epilepsy may cause further cell loss. Biochemical hallmarks associated with apoptosis have been identified in hippocampal and neocortical material removed from patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy: altered expression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family genes and increased expression of caspases and the presence of their cleaved forms. However, apoptotic cells are rarely detected in such patient material and there is evidence of anti-apoptotic signaling changes in the same tissue, including upregulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-w. From animal studies there is evidence that both brief and prolonged seizures can cause neuronal apoptosis within the hippocampus. Such cell death can be associated with caspase and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein activation. Pharmacological or genetic modulations of these pathways can significantly influence DNA fragmentation and neuronal cell death after seizures. Thus, the signaling pathways associated with apoptosis are potentially important for the pathogenesis of epilepsy and may represent targets for neuroprotective and perhaps anti-epileptogenic therapies.

Keywords: Apoptosis, epilepsy, epileptogenesis, hippocampal sclerosis, necrosis, programmed cell death

Overview

Epilepsy is a common chronic neurological disorder which has long been associated with a specific neuropathology. Post mortem studies in the 19th century on tissue from patients with epilepsy noted cell loss, particularly within the brain region called the hippocampus. Was this cause or consequence, or both, of seizures in the brain? The advent of animal models meant this could be formally tested: when normal animals were subjected to prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) or repeated brief seizures, cell death occurred in the hippocampus and certain interconnected brain regions. The pioneering work of the John Olney and Brian Meldrum laboratories provided evidence that seizure-induced cell death resulted from over-activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors. In the past ten years, researchers have found molecular “signatures” of gene-directed cell death signaling programmes linked to apoptosis in brain samples from a sub-population of epilepsy patients – those with pharmacoresistant epilepsy who experience frequent seizures. Using animal models, researchers have shown that experimentally-evoked seizures or epilepsy often activate the same signaling pathways, and drugs or genetic modulation of these cascades can reduce brain injury. This review describes the clinical findings alongside explaining what we are learning from animal models about apoptosis, Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in seizure-induced cell death and epilepsy.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder which affects about 1% of the population. The cardinal feature is a predisposition to recurring episodes of seizures – the results of abnormally synchronized neuronal discharges which disrupt the function of the brain region(s) from which they originate or through which they pass. There are about 40 clinically distinct syndromes. Seizures can cause a spectrum of effects for the patient, ranging from auras and feelings of déjà vu, altered autonomic functions, through to loss of consciousness and motor changes including convulsions [1]. In adults, the most common form is temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). This involves brain structures such as the hippocampus. Treatment of epilepsy is primarily with anti-epileptic drugs which work through mechanisms that subdue excitatory and/or increase inhibitory neurotransmission [1].

Etiology

The cause(s) of epilepsy is often unknown. Epilepsy and TLE in particular, can be acquired following insults to the brain, including head injury, stroke and tumor [1]. Full discussion of the mechanisms implicated in the pathogenesis of symptomatic epilepsy is beyond the scope of the present review and has been covered elsewhere [2-6]. Briefly, such injuries invariably set in motion various cell and molecular processes including neuronal death, gliosis, inflammation and vascular changes, altered expression of ion channels, neurogenesis and re-wiring. Collectively, the process is known as epileptogenesis. A small number of inherited forms of epilepsy are also known [1]. These usually result from gene mutations encoding ion channels, for example potassium or sodium channels. However, for the majority of the sporadic epilepsy population a rather less defined inheritable component exists, which suggest a combination of genetic and environmental factors [7].

Cell death in epilepsy

Hippocampal pathology: cause and consequence of seizures?

Temporal lobe epilepsy is most commonly associated with a lesion known as hippocampal sclerosis [8]. This features selective loss of neurons and atrophy of the brain structure. Cell loss is typically asymmetric between the hippocampi. The most affected regions are the CA (cornu ammonis) 1 subfield and hilar region of the dentate gyrus but the CA3 subfield also commonly displays cell loss. The CA2 subfield and granule cells of the dentate gyrus usually show much less cell loss. Additional features can include axonal sprouting and dispersion of neurons within the dentate granule cell layer of the hippocampus [8, 9].

One of the oldest questions in the field is whether this pathology is casual for epilepsy, a result of ongoing seizures or both. The advent of animal models has provided important answers. Spontaneous (i.e. epileptic) seizures probably do not cause significant neuronal death in the brain [10]. That said, longitudinal imaging of patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy support recurring seizures as a cause of further damage [11-13]. Experimentally-evoked seizures in animals, particularly if resulting in status epilepticus, cause cell loss within the hippocampus in a pattern closely resembling pathology in TLE patients [3, 14]. This has been shown for various species, including primates.

Whether cell loss per se is an essential component of epileptogenesis remains controversial. Prolonged hyperthermia-induced seizures in immature rats cause no permanent cell loss but nevertheless lead to the development of epilepsy in a sub-population [15]. Similarly, antagonists of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors can profoundly reduce hippocampal damage after status epilepticus but rats nevertheless develop epilepsy [16]. Andre et al. found that electroshock seizures suppressed development of epilepsy in rats following status epilepticus independently of protection against damage [17]. However, the importance of cell loss during the initial precipitating injury is supported by recent evidence that protecting hippocampal CA3 neurons by epileptic preconditioning prior to status epilepticus reduced numbers of epileptic seizures recorded in mice by over 50 % [18]. Also, the application of continuous EEG recording in rodents following status epilepticus has demonstrated that the period from injury to first epileptic seizure can be as short as two or three days [19, 20]. Such a short time frame coincides with degeneration of vulnerable cell populations rather than protracted re-wiring processes [3]. Understanding seizure-induced neuronal death therefore offers potential strategies for neuroprotection and, perhaps anti-epileptogenesis.

Mechanisms of cell death after seizures

The primary cause of neuronal death following seizures is probably over-activation of ion channels gated by glutamate, the principal neurotransmitter in the brain [14]. Neurons become flooded with sodium and calcium which causes swelling, membrane rupture and cell lysis. There is also energy failure, production of free radicals, activation of various proteases and DNA degradation [14]. Glutamate receptor-blocking drugs are neuroprotective but also disrupt normal brain function [14]. During the mid-1990s, research on seizure-induced cell death identified features that indicated a programmed or gene-based mechanism. This led to the hypothesis that apoptosis or its molecular machinery may also contribute to cell death [21].

Apoptosis signaling pathways

Apoptosis is a physiological process for removing unwanted cells during development and for maintaining tissue homeostasis. Described by Kerr and colleagues [22], cells condense, DNA is fragmented and the cell contents are dispersed for phagocytosis by surrounding cells. Recent detailed reviews on the molecular pathways that control apoptosis can be found elsewhere [23, 24]. Briefly, two principal pathways have been described. The extrinsic pathway is initiated by cell surface-expressed death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily. Once activated, for example by Fas ligand, receptors oligomerize, recruit intracellular adaptor proteins and form scaffolding complexes [25]. The intracellular adaptor for TNFR1 is the TNFR associated death domain (TRADD), while FADD (Fas-associated death domain) is recruited for Fas signaling [25]. The complexes recruit one or more members of the caspase family of cell death protease, classically caspase-8. Unlike Fas, TNFR1 signaling only leads to apoptosis when survival signaling by nuclear factor ĸB is blocked, for example during translation inhibition [26]. Cleavage of caspase-8 leads to formation of an active enzyme comprising p20 and p10 heterotetramer. This activated initiator caspase cleaves downstream effector caspases, in particular caspase-3. Caspase-3 then cleaves a large number of intracellular substrates, now numbering ∼400 which culminate in the morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis [23]. The second pathway, and the one thought most relevant to seizure-induced neuronal death, is the intrinsic pathway. Induction of this arises from disturbances from within the cell including DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, calcium overload and withdrawal of survival factors. The apical effectors of the intrinsic pathway appear to be members of the Bcl-2 homology domain 3-only (BH3) subgroup of the Bcl-2 gene family. BH3-only proteins comprise a group of at least eight members that include Bcl-2-associated death protein (Bad) [27] and Bcl-2-interacting mediator of death (Bim) [28]. Bid (Bcl-2 interacting death protein) [29] is unusual in that its proapoptotic function appears to be released following cleavage either by caspase-8 or calpains, and it may function as a bridge between the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways in certain cells. BH3-only proteins function by activating so-called multidomain pro-apoptotic Bax/Bak (which contain three of four possible BH domains) either through direct binding or indirectly by binding and inhibiting antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members [24]. The potency of individual members appears to reside with their relative affinities for antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members [30]. These interactions typically occur in the cytosol and at the outer mitochondrial membrane culminating in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization [31]. Thereafter, apoptogenic molecules are released from mitochondria, including cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and a small number of other proteins. In the cytosol, cytochrome c binds the apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (APAF-1) along with dATP which in turn recruits and activates caspase-9 followed by caspase3 [32]. Other hallmarks of apoptosis include the fragmentation of DNA by the caspaseactivated DNase (CAD) into ∼200 b.p. segments, which can be detected by biochemical techniques such as terminal deoxynucleotidyl dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), nuclear condensation, blebbing and dispersal of apoptotic bodies to be removed by surrounding cells [23].

First indicators that seizure-induced neuronal death may feature apoptosis “programs”

Early evidence of a “programmed” element to seizure-induced neuronal death came from two separate observations. First, inhibition of new protein synthesis reduced kainic acid-induced neuronal death in vivo [33]. That is, new gene synthesis was required for some element of the cell death process, which would be compatible with apoptosis. Second, the p53 tumor suppressor gene was induced by seizure-like insults [34] and mice lacking p53 were resistant to excitotoxicity [35]. Other early evidence included the observation that cells deficient in Bax were resistant to excitotoxicity [36] and degenerating neurons after seizures stained for the type of DNA fragmentation present during apoptosis [37]. Some of these findings have subsequently been questioned, including the requirement for Bax [38] and new protein synthesis [39]. Nevertheless, these early studies formed the basis of a now large series of studies by a variety of laboratories to determine whether apoptosisassociated signaling pathways contribute to seizure-induced neuronal death and critically, if they are relevant to human epilepsy.

Apoptosis and apoptosis-associated signaling in human epilepsy

Altered Bcl-2 and Caspase family genes in human epilepsy

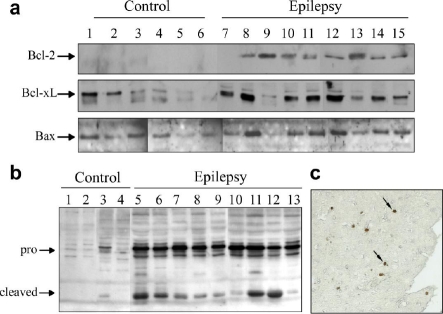

While a brief report in 1998 had mentioned increased Bax immunostaining in hippocampus from TLE patients [40], the first major study addressing apoptosis in human epilepsy was published in 2000 by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh [41]. This study examined protein levels of key genes in the Bcl-2 and caspase families in neocortex samples surgically removed from TLE patients with intractable seizures. The study found significantly higher levels of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL compared to autopsy controls (Figure 1a). Levels of Bcl-xL positively correlated with patient seizure frequency [41]. The expression of Bax was not significantly higher than in controls. For caspase-1, which is associated with pro-inflammatory responses (processing of interleukin 1β) expression of the pro-form was found to be lower in patients and the cleaved (activated) subunit was highly expressed [41]. For caspase-3, both full-length and cleaved forms were more abundant in TLE samples compared to controls (Figure 1b). This study suggested that both pro- and anti-apoptotic pathways were being modulated in human TLE. The implications were that over time this might underlie progressive damage in some patients. However, the study had certain caveats. Like all such studies, the autopsy control material has limitations as a means to compare to surgically obtained samples from patients with a history of seizures and medication. Nevertheless, this and other studies have since reported a range of constitutive and non-constitutive proteins in such material which match experimental control material, indicting broad suitability. Second, the neocortex is not the major site of pathology in human TLE, but rather the hippocampus. Are these pathways also modulated in hippocampus?

Figure 1.

Alterations in Bcl-2 and caspase gene family protein expression and DNA damage in human TLE. (a,b) Western blots showing expression of (a) Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bax in neocortex from autopsy control (lanes 16) and surgically obtained material from epilepsy patients (lanes 7-15). Note expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL is higher while Bax levels are similar between groups. (b) Westen blot analysis of pro- and cleaved caspase-3 in neocortex from the same study. Note, both bands are higher in TLE patient samples. (c) TUNEL staining of neocortex section from one patient. Arrows indicate positive cells. Modified with permission from Henshall et al. (2000) Neurology 55: p250-257 [41]. Copyright © 2000 AAN Enterprises, Inc.

Additional Bcl-2 and caspase family genes altered in human epilepsy

Analysis of hippocampus from patients with intractable TLE from several groups has confirmed altered expression of Bcl-2 and caspase family genes (Tables 1 and 2). A range of caspases are altered in TLE patient brain. These differences are found both in levels of the zymogen form and cleaved subunits. Reports have shown increased procaspases 2, 6, 7, 8 and 9 in human TLE, while cleaved subunits of caspases 3, 7, 8 and 9 have also been found (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of human data on caspase expression in neocortex and hippocampus from patients with intractable TLE

| Brain region | Caspase | Expression vs control | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neocortex | Caspase-1 | Pro-form lowerb | [41] |

| Cleaved higherb | |||

| Hippocampus | Caspase-2 | Highera,c | [72] |

| Hippocampus | Caspase-3 | Cleaved highera | [45] |

| Highera,c | [44] | ||

| Neocortex | Caspase-3 | Pro-and cleaved forms highera,b | [41] |

| Not differentc | [121]d | ||

| Hippocampus | Caspase-6 | Pro-form higherb | [79] |

| Hippocampus | Caspase-7 | Pro-form higherb | [79] |

| Cleaved higherb | |||

| Hippocampus | Caspase-8 | Cleaved higherb | [100] |

| Hippocampus | Caspase-9 | Pro-form higherb | [79] |

| Cleaved highera,b |

Assessed by immunohistochemistry;

Assessed by Western blotting;

distinction between pro- and cleaved not made.

No actual data was presented.

Table 2.

Summary of human data on Bcl-2 family protein expression in neocortex and hippocampus from patients with intractable TLE

| Brain region | Gene | Expression vs control | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | Bcl-2 | Highera | [44, 46] |

| Neocortex | Bcl-2 | Highera, b | [41] |

| Hippocampus | Bcl-xL | Not differentb | [52] |

| Neocortex | Bcl-xL | Highera,b | [41] |

| Hippocampus | Bcl-w | Higherb | [52] |

| Hippocampus | Bax | Highera | [46] |

| Hippocampus | Bax | Not differentb | [52] |

| Hippocampus | Bax | Not differenta,c | [44] |

| Neocortex | Bax | Not differenta,b,c | [41] |

| Hippocampus | Bad | Not differentb | [42] |

| Hippocampus | Bid | Not differentb,d | [42, 79] |

| Hippocampus | Bim | Lowerb,e | [42, 79] |

Assessed by immunohistochemistry

Assessed by Western blotting

Tendency to higher expression

Cleaved form not reported.

Binding of Bim to Bcl-w also evident.

A complex pattern of differences in Bcl-2 family protein expression between control and patient material is evident (Table 2). Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bcl-w have been reported to be higher in TLE than control in several studies. However, some pro-apoptotic changes are also seen in this gene family. Expression of Bax shows moderate or no overexpression in patient material. However, Bax is expressed constitutively in brain and may therefore not require induction for functional involvement. A number of BH3-only proteins have been reported, with consistently lower levels of Bcl-2-interacting mediator of death (Bim) reported. Levels of most others are similar to control (Table 2). Does this suggest pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins are not important? Not necessarily. To date, very few have been studied in any detail. Moreover, assays which yield information about the function of these proteins (co-immunoprecipitation of Bcl-2 family protein complexes from affected tissue) have found increased Bim binding to anti-apoptotic Bcl-w, a conformation associated with Bcl-w inactivation during apoptosis [42].

DNA fragmentation in human TLE brain

Several groups have examined TLE patient material for the presence of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL), a marker of irreversible DNA fragmentation. In our own studies, we detected TUNEL positive cells in neocortex from some patients, but they were in the minority (Figure 1c) [41]. We have also found occasional TUNEL positive cells with apoptoticlike morphology in hippocampus from TLE patients [43]. Other groups have reported apoptosis-like cell morphology in sub-groups of patients at ultrastructural level [44]. There is also increased nuclear localization of CAD in TLE patient hippocampus [45]. In the same study, two other putative DNases, AIF and endonuclease G did not appear to be significantly activated in patient material [45]. However, to date TUNEL counts have not been found statistically different to controls in these and other studies [44-46].

Summary of human data: do repeated epileptic seizures in TLE patients cause apoptosis?

Is there apoptotic cell death in human TLE? The evidence does not yet support this conclusion, but the inherent single time point sampling with human material makes definitive estimates of incidence difficult. Also, relatively small cohorts have been studied to date. However, the biochemical data suggest ongoing pathogenic processes in epilepsy and/or frequent epileptic seizures per se alter the molecular repertoire of two key families of apoptosis-associated genes in the brain. Are the gene changes causing or indeed preventing further neuronal loss? The evidence of up-regulated anti-apoptotic genes may support adjustment of the apoptotic repertoire in human epileptic brain to a protective balance. However, it is tempting to speculate that because of the cleaved caspases detected in such material this is insufficient and thus apoptosis might contribute to the accumulation of neuronal loss over time in some patients.

Apoptosis and apoptosis-associated signaling pathways in rodent models

Apoptosis after single and repeated brief seizures

The occurrence of apoptosis has been analyzed following evoked single or repeated brief seizures, prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) and spontaneous seizures (epileptic animals). Sloviter et al. showed by electron microscopy that neuronal apoptosis occurs in the adult rat hippocampus after non-convulsive seizures induced by electrical stimulation of the perforant path [47]. However, apoptotic cells were restricted to the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus. In contrast, the morphology of dying hilar and CA3 pyramidal neurons was reported as necrotic [47]. Single non-convulsive seizures induced by electrical stimulation of the rat hippocampus or brief single seizures after electrical stimulation of the amygdala also cause dentate granule cell apoptosis [48, 49]. Repeated seizures in these animals caused more cells to undergo apoptosis [48, 49]. Electrical stimulation of the amygdala also caused induction of bax although this did not necessarily co-localize with apoptotic cells [49, 50]. Interestingly, after electroshock seizures in rats or mice there is a shift toward increased levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins [42, 51, 52]. This may underlie neuroprotective effects. Indeed, damage after status epilepticus is reduced when preceded by electroshock seizures [42, 51, 52]. Thus, where brief seizures result in cell death there is a pro-apoptotic biochemical response, while non-damaging seizures in fact suppress apoptosis signaling pathways.

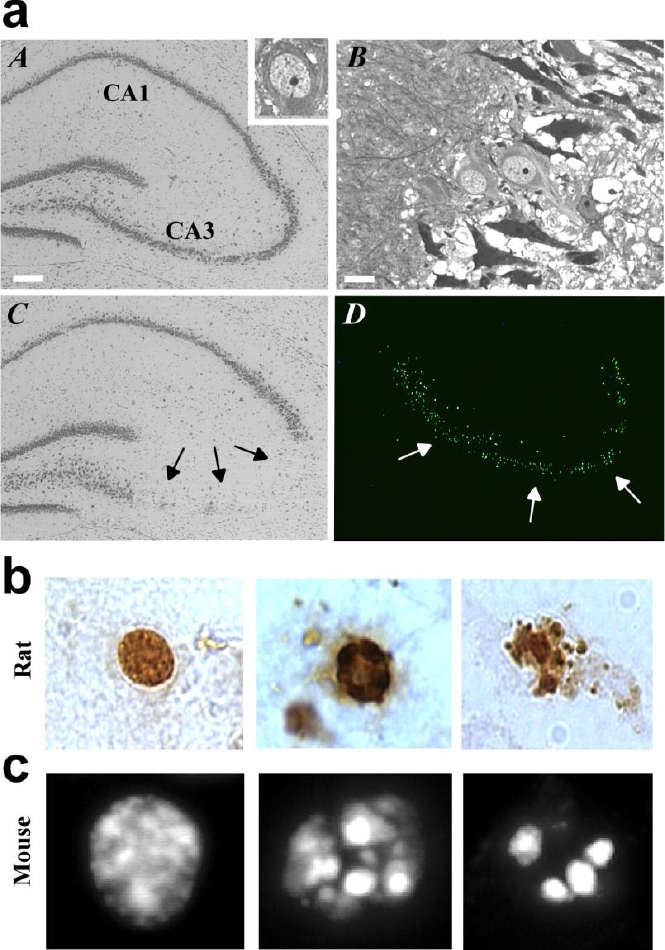

Apoptosis after experimental status epilepticus

What about after prolonged seizures? It is well established that experimental status epilepticus in adult rats induced via a variety of electrical or chemoconvulsive methods causes extensive cell death within the hippocampus. Individual mouse strains show considerable variability in seizure-damage vulnerability but all undergo hippocampal damage after status epilepticus [53, 54]. Extra-hippocampal areas including neocortex and thalamus are also commonly damaged where systemic convulsants are employed [3]. Degenerating neurons in such models display DNA fragmentation in these regions. As an example, we characterized robust single- and double-stranded DNA fragmentation in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons after focal-onset status epilepticus at 24 h [55, 56] (Figure 2a). Are these cells apoptotic? In the rat, the fragmented DNA in these dying cells is rather evenly distributed and apoptotic morphology is rare (Figure 2b). In mice subjected to status epilepticus using the same focal-onset approach, neurons throughout CA3 become strongly TUNEL positive and apoptoticlike nuclear morphology is apparent in ∼30 % of cells [57] (Figure 2c). Thus, prolonged seizures can cause apoptosis in hippocampal subfields in addition to the dentate granule cell layer. Model, age, species and/or strain differences influence the extent. Indeed, some groups have not reported strong DNA fragmentation profiles. Fujikawa and co-workers reported most dying neurons after generalized status epilepticus caused by the cholinergic agonist pilocarpine appeared necrotic and cells were mainly TUNEL negative [58, 59].

Figure 2.

Hippocampal damage after experi-mental status epilepticus and morphology of TUNEL positive cells. (a) A, Photomicrograph showing hippocampus of a rat that received intra-amygdala injection of vehicle. Inset shows a normal CA3 neuron at high magnification. B, CA3 subfield in a rat 4 h after status epilepticus revealing early degenerative changes (dark cells) in some neurons. C, View of a rat hippocampus 24 h following status epilepticus revealing CA3 neuron loss (arrows). D, Example of TUNEL stained CA3 subfield (green) 24 h after status epilepticus. Scale in A is 200µm; B is 15µm. (b) Examples of the morphology of TUNEL positive CA3 cells after status epilepticus in the rat showing (left) a cell without apoptotic features, while (middle, right) TUNEL labeled nuclei exhibiting chromatin marginalization, clumping and blebbing. (c) Examples of TUNEL positive CA3 cells in mice after status epilepticus showing (left) cell without apoptotic features and (middle, right) cells with apoptotic morphology. Modified with permission from (a) Henshall et al. (2002) J. Neuroscience 22, 8458-8465 [56], Copyright © 2002 Society for Neuroscience. (b) Henshall et al. (2002) Neurobiol. Dis. 10, 71-87 [69], Copyright © 2002 Elsevier Science (USA), and (c) Shinoda et al. (2004) J. Neurosci. Res. 76: 121-128 [57] Copyright © 2004 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Molecular signature of apoptosis after status epilepticus: mitochondrial dysfunction and caspsase induction

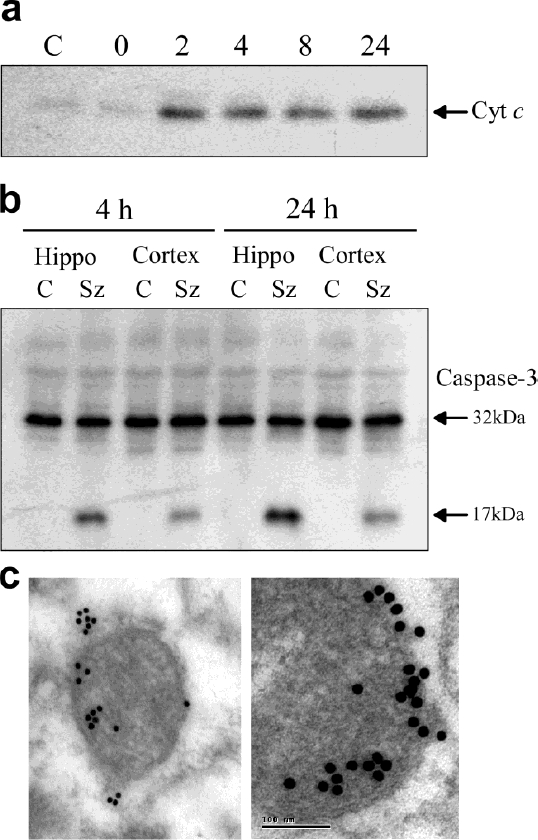

While recognizing that no single biochemical test unequivocally identifies cell death as apoptotic, the cell death accompanying status epilepticus in many models features a molecular “signature” consistent with apoptosis. A key event in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is cytochrome c release from mitochondria [21]. We have shown this occurs in rat hippocampus within 2 h of status epilepticus [60] (Figure 3a). The same result was reported by an independent group using the same model [61]. Other groups have shown cytochrome c release following intra-hippocampal kainic acid injection [62], while cytochrome c release was not detected after systemic kainic acid [63].

Figure 3.

Release of cytochrome c and caspase-3 cleavage following experimental status epileptics. Data from rats subject to status epilepticus induced by intra-amygdala kainic acid. (a) Western blot analysis of cytochrome c (Cyt c) in the cytoplasmic fraction of the rat hippocampus in control (C) rats and rats at various times following status epilepticus. The 0 h time point coincides with injection of anticonvulsant, 40 minutes after intra-amygdala kainic acid. Note the presence of “released” cytochrome c at 2 h. (b) Western blot of pro-caspase-3 (32 kDa) and the cleaved form (17 kDa) in hippocampus and cortex from control rats (C) and rats subject to prolonged seizures by intra-amygdala kainic acid (Sz). (c) Electron microscopy images of Bax-gold particles (15 nm) clustering at mitochondria in the CA3 subfield 2 h after status epielpticus. (a, b) Modified with permission from Henshall et al. (2000) J. Neurochem. 74: 1215-1223 [60]. Copyright © 2000 International Society for Neurochemistry. (c) Modified with permission from Henshall et al. (2002) J. Neuroscience 22, 8458-8465 [56], Copyright © 2002 Society for Neuroscience.

Downstream, there is evidence of apoptosome formation (APAF-1 interaction with cytochrome c) in hippocampus after seizures caused by intra-amygdala kainic acid [64]. In the same model, the presence of cleaved caspase-3 is evident by 4 h after seizures, with levels and activity peaking at 24 h [60] (Figure 3b). Caspase-3 cleavage is also evident in the neocortex of rats after status epilepticus [60] (Figure 3b). Work from multiple laboratories has demonstrated status epilepticus in rats or mice using different induction methods activate caspases 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9 [52, 60, 61, 64-73]. Caspase induction also seems to correlate to specific EEG patterns of seizure type and duration [69, 74]. If clinically relevant, this might have value for informing on pathologic versus benign seizures and neuroprotective treatment thereof.

Contrasting the above findings, some groups have not detected caspase activation during cell death after status epilepticus [58, 59, 63]. However, in the model used by Fujikawa and co-workers they also reported only minimal TUNEL staining in degenerating neurons [58, 59]. Reports from two other laboratories suggested induction of caspase-3 in hippocampus peaked several days after initial status epilepticus and was therefore unlikely to have an important role in acute cell death [74, 75]. Again however, the models used were not associated with strong, early hippocampal TUNEL staining. Taken together, these studies show cell death following seizures in certain models can occur without an apoptotic signature. Where there is strong DNA fragmentation/TUNEL staining, a robust caspase response is often present.

Caspase inhibitors reduce DNA fragmentation and neuronal death after status epilepticus

The effects of pseudo-substrate caspase inhibitors have been tested against seizure-induced neuronal death in vivo by several independent groups. Inhibitors of caspases 3, 8 and 9 all reduce status epilepticus-induced DNA fragmentation (as assessed by the TUNEL technique) and/or neuronal death (Table 3). The degree of protection is variable. Reductions in TUNEL counts can exceed 50 %, while surviving neuron counts tend to be closer to 30 %. Since inhibition of caspases typically had a greater effect on DNA damage than cell survival, caspases may be better at blocking biochemical features of cell death rather than permanently preventing cell demise. Over-expression of the baculoviral caspase inhibitor p35 via transgenic or viral vector approaches is also protective against seizure-like insults in vivo [66, 76] (Table 3). These studies provide evidence for a causal role for caspases in seizure-induced neuronal death, at least in the models tested. Monitoring and quantification of EEG in these studies also determined caspase inhibitors did not alter resting or seizure EEG, indicating they do not overly interfere with brain function under normal or pathological conditions [60, 67, 77].

Table 3.

Summary of caspase activation after experimental seizure-induced neuronal death and the effects of caspase inhibitors on seizure-damage

| Inhibitor | Model | Time period and method of assessment | Hippocampal TUNEL counts | Hippocampal CA3 survivala | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-1 | ESA | n.d. | n.d. | No effectb | [77] |

| Caspase-3 | IAK | 4-24 h (WB, A) | n.d. | Increased | [60] |

| ESA | n.d. | n.d. | Increased | [77] | |

| Caspase-8 | IAK | 0-72 h (WB, A) | Reduced | Increased | [67] |

| IAK | 0-72 h (WB) | Reduced | Increased | [61] | |

| Caspase-9 | IAK | 4-72 h (WB, A) | Reduced | Increased | [64] |

| IAK | 4-72 h (WB) | Reduced | Increased | [117] | |

| ESA | n.d. | n.d. | Increased | [77] | |

| viral p35 | SK | 8 h (A) | Reduced | n.d. | [66] |

Data are for CA3 subfield of the hippocampus. Inhibitors were: Ac-YVAD-cmk (caspase-1), z-DEVD-fmk (caspase-3), z-IETD-fmk (caspase-8) and z-LEHD-fmk (caspase-9).

Assessments made on either degenerating or remaining neurons in the CA3 part of the hippocampus.

Tendency to neuroprotection seen in dentate gyrus. Key: n.d., not determined; ESA, electrical stimulation of the amygdala; IAK, intra-amygdala kainic acid; SK, systemic kainic acid; WB, Western blot, A, enzyme assay.

Effect of caspase inhibitors on epilepsy development after status epilepticus

Narkilahti et al. evaluated whether caspase inhibition influenced the process of epileptogenesis. Their study reported that rats treated for one week with a caspase-3 inhibitor after status epilepticus developed a similar epileptic phenotype as the vehicle group [77]. However, two important points should be raised before dismissing anti-epileptogenic effects of caspase inhibitors. First, inhibitor administration began three hours after status epilepticus [77] so additional neuroprotective effects may have been missed. Second, two long-term studies were performed in the paper by Narkilahti et al. [77]. In the first, using a seven week interval between status epilepticus and epilepsy monitoring, the caspase inhibitor-treated rats developed significantly fewer epileptic seizures than the vehicle controls: anti-epileptogenic effects of caspase inhibition were evident. This anti-apileptogenic effect was not evident in the second (longer follow-up) study. Alternative dosing regimes in models associated with greater activation of caspases and DNA fragmentation might yield clearer effects of caspase inhibition of post-status epilepticus epileptogenesis.

Involvement of caspases in experimental epileptogenesis and chronic epilepsy

Both caspases 2 and 3 are up-regulated in rat hippocampus after status epilepticus during the period associated with epileptogenesis [72, 74, 78]. Moreover, upregulation and activity appears to be maintained in animals once epileptic. This suggests caspases may have roles beyond control of cell death in epilepsy, highlighting potentially novel disease mechanisms for caspases. Of note, caspase-2 stained neuronal processes during epileptogenesis and in chronically epileptic animals [72, 78]. Similar patterns of neuronal process staining for caspases 2 and 9 is evident in hippocampus from TLE patients [72, 79].

Interpretation of caspase inhibitor studies: does the “C” in ABCs stand for Controversy?

The role of caspases in neurological insults in adult brain remains controversial and several caveats exist with the caspase inhibitor data. First, in vitro and in vivo data have been presented showing neuronal death after seizure-like insults or status epilepticus is unaffected by caspase inhibitors [58, 80, 81]. Second, there is evidence that key apoptosisregulatory genes including APAF-1 are downregulated in adult brain such that insults preferentially activate non-caspase pathways [82, 83]. Third, neuroprotection by pseudosubstrate caspase inhibitors may arise in part via non-specific effects against calpains and cathepsins [84-86]. On this last point, it has been noted by several groups that reduced DNA fragmentation or neuroprotection by caspase inhibitors extends to brain regions not displaying caspase activation after seizures [60, 77, 87]. Thus, where evident, effects of pseudosubstrate-based caspase inhibitors in vivo may derive in part from contributions by other caspases or non-caspase cell death proteases.

Bcl-2 family proteins

There is good evidence that members of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family are activated during seizure-induced neuronal death in rats and mice (Table 4). Expressional responses for several members of the family, in particular Bax and Bcl-xL are often not found after seizures [56, 88]. Rather, evidence of involvement comes from functional studies performed by co-immunoprecipitation of various Bcl-2 family member complexes. Status epilepticus causes activation (de-phosphorylation) and dissociation of Bad from its chaperone 14-3-3 and translocation and binding to anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL [56, 89]. Seizures also trigger cleavage of Bid [67, 90] and overexpression of Bim [42] (Table 4). Bax has also been detected in clusters on the outer surface of mitochondria [56] (Figure 3c).

Table 4.

Bcl-2 family member responses during seizure-induced neuronal death and effects of expressional modulation

| Gene | Species | Model | Response to seizures (≤ 24h) | Effect of modulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bcl-2 | Rat | SK | Upregulated | n.d. | [122] |

| Rat | IVK | Upregulated | n.d. | [123] | |

| Rat | IAK | Upregulated | n.d. | [89] | |

| Rat | SK | Not changed | n.d. | [88] | |

| Rat | IHK | n.d. | Overexpression protective | [91] | |

| Bcl-xL | Rat | IAK | No change | n.d. | [56] |

| Rat | SK | No change | n.d. | [88] | |

| Mouse | IAK | No change | n.d. | [52] | |

| Rat | SK | n.d. | Overexpression protective | [92] | |

| Bcl-w | Rat | IAK | Upregulated | n.d. | [124] |

| Rat | PILO | Upregulated | n.d. | [125] | |

| Rat | IVK | Down-regulated | n.d. | [123] | |

| Mouse | IAK | Down-regulated | Damage worse in bcl-w-/- | [52] | |

| Bad | Rat | IAK | Activated | Inhibition protectivea | [56] |

| Rat | IAK | Activated | n.d. | [89] | |

| Mouse | SK | Activated | Inhibition protectivea | [126] | |

| Bid | Rat | IAK | Activated | n.d. | [67] |

| Rat | IAK | Activated | n.d. | [90] | |

| Rat | IAK | Activated | n.d. | [61] | |

| Bax | Rat | SK | No change | n.d. | [88] |

| Rat | IAK | No changeb | n.d. | [56] | |

| Rat | SK | No change | n.d. | [63] | |

| Rat | IAK | No change | n.d. | [52] | |

| Mouse | SK | Small increase | n.d. | [70] | |

| Bim | Rat | IAK | Upregulated | Damage reducedc | [42] |

| Rat | PILO | Upregulated | n.d. | [125] | |

| Rat | IVK | Downregulated | n.d. | [123] | |

| Mouse | IHK | n.d. | Damage same in bim-/- | [95] |

Both FK506 and ketogenic diet used to prevent Bad activation have other mechanisms of action.

However, Bax accumulated at mitochondria.

Assessment made in vitro only. Key: n.d. not determined; ESA, electrical stimulation of the amygdala; IAK, intra-amygdala kainic acid; IHK, intra-hippocampal kanic acid; IVK, intra-ventricular kainic acid; SK, systemic kainic acid; PILO, pilocarpine;

However, anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins are also regulated in such tissue. Bcl-2 is commonly reported as up-regulated during seizure-induced neuronal death (Table 4).

In addition to these descriptive studies, causal roles for several members of the Bcl-2 family have been demonstrated (Table 4). Sapolsky's group showed that viral transfection of rats with Bcl-2 was neuroprotective in a model of seizure-induced neuronal death [91]. Complementing this approach, Bcl-xL over-expression using Tat fusion protein reduced neuronal death after seizures in rats [92]. Thus, while expressional differences exist between Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in terms of their constitutive and seizure-induced responses, either can protect against neuronal death when overexpressed. Conversely, mice lacking Bcl-w were found to display more hippocampal cell death after status epilepticus than their wild-type littermates, indicating endogenous protective roles for this gene [52].

Functional evidence for pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members is rather less certain. Pharmacological block of Bad by calcineurin inhibition is neuroprotective, but this drug has other mechanisms of action that could explain this finding [56]. Bak deficient mice were found, rather counter-intuitively, to be more vulnerable to seizure-induced neuronal death [93]. Two BH3-only protein deficient studies are relevant. First, mice deficient in Puma were found to be equally vulnerable as wild-types to N-methyl-d-aspartate-induced hippocampal injury in vivo [94]. Second, bim-/- mice were found to be similarly vulnerable in vivo to excitotoxicity as wild-type animals [95]. However, both these studies used models of direct intra-hippocampal excitotoxin injection, where dissociation of seizure effects versus direct toxicity is not possible. Also, the Theofilas study did not report data on Bim expression, nor hippocampal CA3 damage comparing bim-/- and wild-type mice. Collectively however, these studies suggest there may be redundancy among BH3-only proteins. If proven accurate, future studies might investigate mice doubly-deficient for BH3-only proteins.

Death receptor signaling in seizure-induced neuronal death

While there has been less focus on the involvement of the death receptor signaling pathway in seizure-induced neuronal death, studies suggest it is activated in vivo after prolonged seizures. Co-immunoprecipitation studies show TNFR1 binding to TRADD and TRADD-FADD binding both increased within the first hours after status epilepticus in rats [96]. Caspase-8 fragments are also present in FADD immunoprecipitates from rat hippocampus after status epilepticus [97]. Caspase-8 is activated in vitro and in vivo after seizures and time course analysis points to early induction [61, 67, 98]. In human brain, death receptors are constitutively expressed [99, 100] and TNFR1-TRADD and TRADD-FADD binding is evident in hippocampal resection specimens from patients with intractable TLE [100]. Functional evidence for involvement of this pathway in seizure-induced neuronal death comes from several observations. Caspase-8 inhibition using the pseudosubstrate z-IETD-fmk reduces neuronal death both in vitro [98] and in vivo [61, 67]. Neutralizing antibodies to TNFα reduced hippocampal cell death in vivo after status epilepticus [96]. However, mice lacking the TNFR1 undergo increased cell death following systemic kainic acid [101]. Thus, the role of death receptor signaling requires additional clarification. In particular, there is no direct evidence that Fas or TNFR1 is driving the formation of these signaling complexes, nor whether these are responsible for caspase-8 cleavage after seizures.

AIF and caspase-independent neuronal death

AIF is a mitochondrial flavoprotein which on translocation to the nucleus induces large-scale DNA fragmentation and nuclear condensation during apoptosis-like cell death [102]. This type of apoptosis is caspaseindependent, and AIF is recognized as an important mediator of neuronal death in models of excitotoxicity [103]. In vitro studies demonstrate that AIF contributes to excitotoxic neuronal death [38, 104]. Furthermore, harlequin mice which display ∼80% lower AIF levels than normal are protected in vivo against hippocampal damage following systemic kainic acid [38]. AIF is also implicated in cell death following traumatic brain injury [105, 106]. A recent study also reported that nuclear condensation was very rapid following AIF translocation to the nucleus in neuron-like cells [107]. Since nuclear pyknosis is evident in many neurons within a few hours of status epilepticus this may be AIF-dependent. Two major mechanisms have been proposed for release of AIF involving poly (ADP ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) [108] and calpain 1 [109, 110]. Full discussion of additional apoptosis-associated genes found regulated in either human or experimental models lies beyond the scope of the present review.

Contribution of glia

Glia are important contributors to mechanisms of ictogenesis, seizure-induced neuronal death and epileptogenesis [111-113]. While glial cell death is not common after status epilepticus, the contribution of glia to apoptosis and as sites of regulated Bcl-2 and caspase family genes has been recognized in several studies. Astrocytes were identified as the cell type expressing elevated Bcl-xL in neocortex from patients with TLE [41]. BH3-only protein Bid was also found, albeit not exclusively, in astrocytes after status epilepticus in rats [67]. Both microglia and astrocytes express several types of caspases following experimental status epilepticus [69, 114]. Indeed, Narkilahti et al. reported the majority of active caspase-3 immunoreactivity localized to astrocytes after status epilepticus in rats [74]. However, this is in contrast to the mainly neuronal expression of caspase-3 and other caspases reported by our group and others [60, 64, 68, 69, 75, 115-117]. In human TLE, caspases are mainly expressed in neurons [41, 72, 79]. Astrocytes and microglia are also the source of several cytokines that influence cell death and epileptogenesis and death receptors of the TNF family are constitutively expressed on glia [99, 118]. The Vezzani group have shown that glia are the source of TNFα [119] and more recently, that caspase-1 contributes to epileptogensis by production of interleukin-1β in astrocytes [120]. Taken together, these data suggest apoptotic pathways are activated in glia during and after seizure-induced neuronal death and these pathways may form part of the glial contribution to neuronal death and the epileptogenic process.

Summary

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurring episodes of seizures. Repeated seizures over time or single prolonged seizures may harm the brain and therefore understanding molecular mechanisms of neuronal death is a route to therapeutic neuroprotective and possibly anti-epileptogenic therapies. Levels of both caspases and Bcl-2 family genes are altered in brain regions affected by repeated seizures in epilepsy patients and repeated brief or single prolonged experimental seizures can cause apoptosis and activate caspases and Bcl-2 family proteins. We have also learnt that apoptosis-associated genes may continue to be active long after the initial injury and perhaps contribute to pathogenic mechanisms underlying the development and maintenance of the epileptic state. Finally, we know that modulating these genes can alter hippocampal damage after seizures. The present review is not exhaustive and we have focused principally on the caspase and Bcl-2 families. Nevertheless, the evidence supports a role for these signaling pathways in seizure-induced neuronal death and the epileptic brain which may form the basis of future efforts at neuroprotection or anti-epileptogenesis.

What problems and questions remain? First, inter-model variability in the apoptotic component has shown neuronal death after seizures does not necessarily involve these pathways. Nevertheless, apoptotic pathways are almost certainly regulated in TLE patient's brain. Thus, focus on models which feature both the main characteristics of experimental epileptogenesis and an apoptotic component remain justified. Second, we need better evidence for whether pro-apoptotic and antiapoptotic signaling changes are occurring in the same or different cells. This is important for both the human and experimental model work. While activated caspases have been reported in neurons after seizures, convincing staining of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in patient or experimental material is lacking. Third, more exact temporal mapping of proapoptotic changes to events such as cytochrome c release and morphological changes. Finally, the role of apoptosis-associated genes in epileptogenesis and maintenance of the epileptic state merits increased attention. Can modulation of Bcl-2 or caspase family members affect damage enough to alter post-status epilepticus development of epilepsy? What is the significance of their modulation in the chronically epileptic brain? Ongoing investigations, in a number of laboratories including our own, aim to provide answers to these questions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following for their generous support: Health Research Board (RP/2005/24), Irish Research Council for Science Engineering and Technology, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS39016, NS41935 and NS47622), Marie Curie Actions (MIRG-CT-2004-014567), Science Foundation Ireland (08/IN1/B1875), and the Wellcome Trust (GR076576MA).

References

- 1.Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1257–1266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vezzani A, Granata T. Brain inflammation in epilepsy: experimental and clinical evidence. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1724–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloviter RS. Hippocampal epileptogenesis in animal models of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis: the importance of the “latent period” and other concepts. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 9):85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scharfman HE. The neurobiology of epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7:348–354. doi: 10.1007/s11910-007-0053-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boison D. The adenosine kinase hypothesis of epileptogenesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitkanen A, Lukasiuk K. Molecular and cellular basis of epileptogenesis in symptomatic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(Suppl 1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavalleri GL, Weale ME, Shianna KV, Singh R, Lynch JM, Grinton B, Szoeke C, Murphy K, Kinirons P, O'Rourke D, Ge D, Depondt C, Claeys KG, Pandolfo M, Gumbs C, Walley N, McNamara J, Mulley JC, Linney KN, Sheffield LJ, Radtke RA, Tate SK, Chissoe SL, Gibson RA, Hosford D, Stanton A, Graves TD, Hanna MG, Eriksson K, Kantanen AM, Kalviainen R, O'Brien TJ, Sander JW, Duncan JS, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Wood NW, Doherty CP, Delanty N, Sisodiya SM, Goldstein DB. Multicentre search for genetic susceptibility loci in sporadic epilepsy syndrome and seizure types: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:970–980. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathern GW, Babb TL, Armstrong DL. Hippocampal Sclerosis. In: Engel JJ, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houser CR. Granule cell dispersion in the dentate gyrus of humans with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 1990;535:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91601-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorter JA, Goncalves Pereira PM, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, Lopes da Silva FH, Lucassen PJ. Neuronal cell death in a rat model for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy is induced by the initial status epilepticus and not by later repeated spontaneous seizures. Epilepsia. 2003;44:647–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.53902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalviainen R, Salmenpera T, Partanen K, Vainio P, Riekkinen P, Pitkanen A. Recurrent seizures may cause hippocampal damage in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1998;50:1377–1382. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tasch E, Cendes F, Li LM, Dubeau F, Andermann F, Arnold DL. Neuroimaging evidence of progressive neuronal loss and dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:568–576. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199905)45:5<568::aid-ana4>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernasconi A, Tasch E, Cendes F, Li LM, Arnold DL. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging suggests progressive neuronal damage in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujikawa DG. Neuroprotective strategies in status epilepticus. In: Wasterlain CG, Treiman DM, editors. Status epilepticus: Mechanisms and management. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2006. pp. 463–480. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dube C, Richichi C, Bender RA, Chung G, Litt B, Baram TZ. Temporal lobe epilepsy after experimental prolonged febrile seizures: prospective analysis. Brain. 2006;129:911–922. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandt C, Potschka H, Loscher W, Ebert U. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade after status epilepticus protects against limbic brain damage but not against epilepsy in kainate model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2003;118:727–740. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andre V, Ferrandon A, Marescaux C, Nehlig A. The lesional and epileptogenic consequences of lithium-pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus are affected by previous exposure to isolated seizures: effects of amygdala kindling and maximal electroshocks. Neuroscience. 2000;99:469–481. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jimenez-Mateos EM, Hatazaki S, Johnson MB, Bellver-Estelles C, Mouri G, Bonner C, Prehn JH, Meller R, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Hippocampal transcriptome after status epilepticus in mice rendered seizure damage-tolerant by epileptic preconditioning features suppressed calcium and neuronal excitability pathways. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bumanglag AV, Sloviter RS. Minimal latency to hippocampal epileptogenesis and clinical epilepsy after perforant pathway stimulation-induced status epilepticus in awake rats. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:561–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.21801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouri G, Jimenez-Mateos E, Engel T, Dunleavy M, Hatazaki S, Paucard A, Matsushima S, Taki W, Henshall DC. Unilateral hippocampal CA3-predominant damage and short latency epileptogenesis after intra-amygdala microinjection of kainic acid in mice. Brain Res. 2008;1213:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liou AKF, Clark RS, Henshall DC, Yin XM, Chen J. To die or not to die for neurons in ischemia, traumatic brain injury and epilepsy: a review on the stress-activated signaling pathways and apoptotic pathways. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:103–142. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor RC, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Apoptosis: controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strasser A, Jost PJ, Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashkenazi A, Herbst RS. To kill a tumor cell: the potential of proapoptotic receptor agonists. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1979–1990. doi: 10.1172/JCI34359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang E, Zha J, Jockel J, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell. 1995;80:285–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor L, Strasser A, O'Reilly LA, Hausmann G, Adams JM, Cory S, Huang DC. Bim: a novel member of the Bcl-2 family that promotes apoptosis. EMBO J. 1998;17:384–395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang K, Yin XM, Chao DT, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. BID: a novel BH3 domain-only death agonist. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2859–2869. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, Colman PM, Day CL, Adams JM, Huang DC. Differential Targeting of Prosurvival Bcl-2 Proteins by Their BH3-Only Ligands Allows Complementary Apoptotic Function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cain K, Bratton SB, Cohen GM. The Apaf-1 apoptosome: a large caspase-activating complex. Biochimie. 2002;84:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreiber SS, Tocco G, Najm I, Thompson RF, Baudry M. Cycloheximide prevents kainate-induced neuronal death and c-fos expression in adult rat brain. J Mol Neurosci. 1993;4:149–159. doi: 10.1007/BF02782498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakhi S, Bruce A, Sun N, Tocco G, Baudry M, Schreiber SS. p53 induction is associated with neuronal damage in the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7525–7529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison RS, Wenzel HJ, Kinoshita Y, Robbins CA, Donehower LA, Schwartzkroin PA. Loss of the p53 tumor suppressor gene protects neurons from kainate- induced cell death. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1337–1345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01337.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang H, Kinoshita Y, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Schwartzkroin PA, Morrison RS. Bax involvement in p53-mediated neuronal cell death. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1363–1373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01363.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pollard H, Charriaut-Marlangue C, Cantagrel S, Represa A, Robain O, Moreau J, Ben-Ari Y. Kainate-induced apoptotic cell death in hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1994;63:7–18. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheung EC, Melanson-Drapeau L, Cregan SP, Vanderluit JL, Ferguson KL, McIntosh WC, Park DS, Bennett SA, Slack RS. Apoptosis-inducing factor is a key factor in neuronal cell death propagated by BAX-dependent and BAX-independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1324–1334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4261-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss S, Cataltepe O, Cole AJ. Anatomical studies of DNA fragmentation in rat brain after systemic kainate administration. Neuroscience. 1996;74:541–551. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagy Z, Esiri MM. Neuronal cyclin expression in the hippocampus in temporal lobe epilepsy. Exp Neurol. 1998;150:240–247. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henshall DC, Clark RS, Adelson PD, Chen M, Watkins SC, Simon RP. Alterations in bcl-2 and caspase gene family protein expression in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2000;55:250–257. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinoda S, Schindler CK, Meller R, So NK, Araki T, Yamamoto A, Lan JQ, Taki W, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Bim regulation may determine hippocampal vulnerability after injurious seizures and in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1059–1068. doi: 10.1172/JCI19971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henshall DC, Schindler CK, So NK, Lan JQ, Meller R, Simon RP. Death-associated protein kinase expression in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:485–494. doi: 10.1002/ana.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu S, Pang Q, Liu Y, Shang W, Zhai G, Ge M. Neuronal apoptosis in the resected sclerotic hippocampus in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schindler CK, Pearson EG, Bonner HP, So NK, Simon RP, Prehn JH, Henshall DC. Caspase-3 cleavage and nuclear localization of caspase-activated DNase in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:583–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uysal H, Cevik IU, Soylemezoglu F, Elibol B, Ozdemir YG, Evrenkaya T, Saygi S, Dalkara T. Is the cell death in mesial temporal sclerosis apoptotic? Epilepsia. 2003;44:778–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.37402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sloviter RS, Dean E, Sollas AL, Goodman JH. Apoptosis and necrosis induced in different hippocampal neuron populations by repetitive perforant path stimulation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;366:516–533. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960311)366:3<516::AID-CNE10>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bengzon J, Kokaia Z, Elmer E, Nanobashvili A, Kokaia M, Lindvall O. Apoptosis and proliferation of dentate gyrus neurons after single and intermittent limbic seizures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10432–10437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang LX, Smith MA, Li XL, Weiss SR, Post RM. Apoptosis of hippocampal neurons after amygdala kindled seizures. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;55:198–208. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akcali KC, Sahiner M, Sahiner T. The role of bcl-2 family of genes during kindling. Epilepsia. 2005;46:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.13904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kondratyev A, Sahibzada N, Gale K. Electroconvulsive shock exposure prevents neuronal apoptosis after kainic acid-evoked status epilepticus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;91:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy B, Dunleavy M, Shinoda S, Schindler C, Meller R, Bellver-Estelles C, Hatazaki S, Dicker P, Yamamoto A, Koegel I, Chu X, Wang W, Xiong Z, Prehn J, Simon R, Henshall D. Bcl-w Protects Hippocampus during Experimental Status Epilepticus. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1258–1268. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schauwecker PE. Complications associated with genetic background effects in models of experimental epilepsy. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)35014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schauwecker PE. Role of genetic influences in animal models of status. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 8):21–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henshall DC, Sinclair J, Simon RP. Spatio-temporal profile of DNA fragmentation and its relationship to patterns of epileptiform activity following focally evoked limbic seizures. Brain Res. 2000;858:290–302. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henshall DC, Araki T, Schindler CK, Lan J-Q, Tiekoter K, Taki W, Simon RP. Activation of Bcl-2-associated death protein and counterresponse of Akt within cell populations during seizure-induced neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8458–8465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08458.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shinoda S, Araki T, Lan JQ, Schindler CK, Simon RP, Taki W, Henshall DC. Development of a model of seizure-induced hippocampal injury with features of programmed cell death in the BALB/c mouse. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:121–128. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fujikawa DG, Ke X, Trinidad RB, Shinmei SS, Wu A. Caspase-3 is not activated in seizure-induced neuronal necrosis with internucleosomal DNA cleavage. J Neurochem. 2002;83:229–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujikawa DG, Shinmei SS, Zhao S, Aviles ER., Jr Caspase-dependent programmed cell death pathways are not activated in generalized seizure-induced neuronal death. Brain Res. 2007;1135:206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henshall DC, Chen J, Simon RP. Involvement of caspase-3-like protease in the mechanism of cell death following focally evoked limbic seizures. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1215–1223. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li T, Lu C, Xia Z, Xiao B, Luo Y. Inhibition of caspase-8 attenuates neuronal death induced by limbic seizures in a cytochrome c-dependent and Smac/DIABLO-independent way. Brain Res. 2006;1098:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chuang YC, Chen SD, Lin TK, Liou CW, Chang WN, Chan SH, Chang AY. Upregulation of nitric oxide synthase II contributes to apoptotic cell death in the hippocampal CA3 subfield via a cytochrome c/caspase-3 signaling cascade following induction of experimental temporal lobe status epilepticus in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1263–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puig B, Ferrer I. Caspase-3-associated apoptotic cell death in excitotoxic necrosis of the entorhinal cortex following intraperitoneal injection of kainic acid in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2002;321:182–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02518-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Henshall DC, Bonislawski DP, Skradski SL, Araki T, Lan J-Q, Schindler CK, Meller R, Simon RP. Formation of the Apaf-1/cytochrome c complex precedes activation of caspase-9 during seizure-induced neuronal death. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:1169–1181. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gervais FG, Xu D, Robertson GS, Vaillancourt JP, Zhu Y, Huang J, LeBlanc A, Smith D, Rigby M, Shearman MS, Clarke EE, Zheng H, Van Der Ploeg LH, Ruffolo SC, Thornberry NA, Xanthoudakis S, Zamboni RJ, Roy S, Nicholson DW. Involvement of caspases in proteolytic cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta precursor protein and amyloidogenic A beta peptide formation. Cell. 1999;97:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Viswanath V, Wu Z, Fonck C, Wei Q, Boonplueang R, Andersen JK. Transgenic mice neuronally expressing baculoviral p35 are resistant to diverse types of induced apoptosis, including seizure-associated neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2270–2275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030365297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Henshall DC, Bonislawski DP, Skradski SL, Meller R, Lan J-Q, Simon RP. Cleavage of Bid may amplify caspase-8-induced neuronal death following focally evoked limbic seizures. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:568–580. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henshall DC, Skradski SL, Bonislawski DP, Lan JQ, Simon RP. Caspase-2 activation is redundant during seizure-induced neuronal death. J Neurochem. 2001;77:886–895. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henshall DC, Skradski SL, Meller R, Araki T, Minami M, Schindler CK, Lan JQ, Bonislawski DP, Simon RP. Expression and differential processing of caspases 6 and 7 in relation to specific epileptiform EEG patterns following limbic seizures. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:71–87. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu XM, Pei DS, Guan QH, Sun YF, Wang XT, Zhang QX, Zhang GY. Neuroprotection of Tat-GluR6-9c against neuronal death induced by kainate in rat hippocampus via nuclear and non-nuclear pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17432–17445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manno I, Antonucci F, Caleo M, Bozzi Y. BoNT/E prevents seizure-induced activation of caspase 3 in the rat hippocampus. Neuroreport. 2007;18:373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Narkilahti S, Jutila L, Alafuzoff I, Karkola K, Paljarvi L, Immonen A, Vapalahti M, Mervaala E, Kalviainen R, Pitkanen A. Increased expression of caspase 2 in experimental and human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuromolecular Med. 2007;9:129–144. doi: 10.1007/BF02685887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Persike DS, Cunha RL, Juliano L, Silva IR, Rosim FE, Vignoli T, Dona F, Cavalheiro EA, Fernandes MJ. Protective effect of the organotelluroxetane RF-07 in pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Narkilahti S, Pirttila TJ, Lukasiuk K, Tuunanen J, Pitkanen A. Expression and activation of caspase 3 following status epilepticus in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1486–1496. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weise J, Engelhorn T, Dorfler A, Aker S, Bahr M, Hufnagel A. Expression time course and spatial distribution of activated caspase-3 after experimental status epilepticus: Contribution of delayed neuronal cell death to seizure-induced neuronal injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roy M, Hom JJ, Sapolsky RM. HSV-mediated delivery of virally derived antiapoptotic genes protects the rat hippocampus from damage following excitotoxicity, but not metabolic disruption. Gene Ther. 2002;9:214–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Narkilahti S, Nissinen J, Pitkanen A. Administration of caspase 3 inhibitor during and after status epilepticus in rat: effect on neuronal damage and epileptogenesis. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:1068–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Narkilahti S, Pitkanen A. Caspase 6 expression in the rat hippocampus during epileptogenesis and epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2005;131:887–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamamoto A, Murphy N, Schindler CK, So NK, Stohr S, Taki W, Prehn JH, Henshall DC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis signaling in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:217–225. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000202886.22082.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tomioka M, Shirotani K, Iwata N, Lee HJ, Yang F, Cole GM, Seyama Y, Saido TC. In vivo role of caspases in excitotoxic neuronal death: generation and analysis of transgenic mice expressing baculoviral caspase inhibitor, p35, in postnatal neurons. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;108:18–32. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verdaguer E, Garcia-Jorda E, Jimenez A, Stranges A, Sureda FX, Canudas AM, Escubedo E, Camarasa J, Pallas M, Camins A. Kainic acid-induced neuronal cell death in cerebellar granule cells is not prevented by caspase inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1297–1307. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yakovlev AG, Ota K, Wang G, Movsesyan V, Bao WL, Yoshihara K, Faden AI. Differential expression of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 and caspase-3 genes and susceptibility to apoptosis during brain development and after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7439–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu CL, Siesjo BK, Hu BR. Pathogenesis of hippocampal neuronal death after hypoxia-ischemia changes during brain development. Neuroscience. 2004;127:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schotte P, Declercq W, Van Huffel S, Vandenabeele P, Beyaert R. Non-specific effects of methyl ketone peptide inhibitors of caspases. FEBS Lett. 1999;442:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Knoblach SM, Alroy DA, Nikolaeva M, Cernak I, Stoica BA, Faden AI. Caspase inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk attenuates calpain and necrotic cell death in vitro and after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1119–1132. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000138664.17682.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bizat N, Galas MC, Jacquard C, Boyer F, Hermel JM, Schiffmann SN, Hantraye P, Blum D, Brouillet E. Neuroprotective effect of zVAD against the neurotoxin 3-nitropropionic acid involves inhibition of calpain. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kondratyev A, Gale K. Intracerebral injection of caspase-3 inhibitor prevents neuronal apoptosis after kainic acid-evoked status epilepticus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;75:216–224. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lopez E, Pozas E, Rivera R, Ferrer I. Bcl-2, Bax and Bcl-x expression following kainic acid administration at convulsant doses in the rat. Neuroscience. 1999;91:1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00704-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li TF, Lu CZ, Xia ZL, Niu JZ, Yang MF, Luo YM, Hong Z. Dephosphorelation of Bad and upregulation of Bcl-2 in hippocampus of rats following limbic seizure induced by kainic acid injection into amygdaloid nucleus. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2005;57:310–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shinoda S, Schindler CK, Lan J-Q, Saugstad JA, Taki W, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Interaction of 14-3-3 with Bid during seizure-induced neuronal death. J Neurochem. 2003;86:460–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Phillips RG, Lawrence MS, Ho DY, Sapolsky RM. Limitations in the neuroprotective potential of gene therapy with Bcl-2. Brain Res. 2000;859:202–206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02453-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ju KL, Manley NC, Sapolsky RM. Anti-apoptotic therapy with a Tat fusion protein protects against excitotoxic insults in vitro and in vivo. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fannjiang Y, Kim CH, Huganir RL, Zou S, Lindsten T, Thompson CB, Mito T, Traystman RJ, Larsen T, Griffin DE, Mandir AS, Dawson TM, Dike S, Sappington AL, Kerr DA, Jonas EA, Kaczmarek LK, Hardwick JM. BAK alters neuronal excitability and can switch from anti- to pro-death function during postnatal development. Dev Cell. 2003;4:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Concannon CG, Ward MW, Bonner HP, Kuroki K, Tuffy LP, Bonner CT, Woods I, Engel T, Henshall DC, Prehn JH. NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal apoptosis in vitro and in vivo occurs in an ER Stress and PUMA independent manner. J Neurochem. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Theofilas P, Bedner P, Huttmann K, Theis M, Steinhauser C, Frank S. The proapoptotic BCL-2 homology domain 3-only protein Bim is not critical for acute excitotoxic cell death. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:102–110. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31819385fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shinoda S, Skradski SL, Araki T, Schindler CK, Meller R, Lan J-Q, Taki W, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Formation of a tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 molecular scaffolding complex and activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 during seizure-induced neuronal death. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2065–2076. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Henshall DC, Araki T, Schindler CK, Shinoda S, Lan J-Q, Simon RP. Expression of death-associated protein kinase and recruitment to the tumor necrosis factor signaling pathway following brief seizures. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:1260–1270. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Meller R, Clayton C, Torrey DJ, Schindler CK, Lan JQ, Cameron JA, Chu XP, Xiong ZG, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Activation of the caspase 8 pathway mediates seizure-induced cell death in cultured hippocampal neurons. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dorr J, Bechmann I, Waiczies S, Aktas O, Walczak H, Krammer PH, Nitsch R, Zipp F. Lack of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand but presence of its receptors in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-j0001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamamoto A, Schindler CK, Murphy BM, Bellver-Estelles C, So NK, Taki W, Meller R, Simon RP, Henshall DC. Evidence of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Exp Neurol. 2006;202:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gary DS, Bruce-Keller AJ, Kindy MS, Mattson MP. Ischemic and excitotoxic brain injury is enhanced in mice lacking the p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1283–1287. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cregan SP, Dawson VL, Slack RS. Role of AIF in caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23:2785–2796. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang H, Yu SW, Koh DW, Lew J, Coombs C, Bowers W, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Apoptosis-inducing factor substitutes for caspase executioners in NMDA-triggered excitotoxic neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10963–10973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3461-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang X, Chen J, Graham SH, Du L, Kochanek PM, Draviam R, Guo F, Nathaniel PD, Szabo C, Watkins SC, Clark RS. Intranuclear localization of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and large scale dna fragmentation after traumatic brain injury in rats and in neuronal cultures exposed to peroxynitrite. J Neurochem. 2002;82:181–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Slemmer JE, Zhu C, Landshamer S, Trabold R, Grohm J, Ardeshiri A, Wagner E, Sweeney MI, Blomgren K, Culmsee C, Weber JT, Plesnila N. Causal role of apoptosis-inducing factor for neuronal cell death following traumatic brain injury. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1795–1805. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Landshamer S, Hoehn M, Barth N, Duvezin-Caubet S, Schwake G, Tobaben S, Kazhdan I, Becattini B, Zahler S, Vollmar A, Pellecchia M, Reichert A, Plesnila N, Wagner E, Culmsee C. Bid-induced release of AIF from mitochondria causes immediate neuronal cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1553–1563. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science. 2002;297:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Polster BM, Basanez G, Etxebarria A, Hardwick JM, Nicholls DG. Calpain I induces cleavage and release of apoptosis-inducing factor from isolated mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6447–6454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]