Abstract

Fever with generalised lymphadenopathy is a common presentation in clinical practice. A degree of lymphadenopathy is frequently a characteristic of established systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but it is rarely the primary presenting feature. A 25-year-old man presented with night sweats, weight loss and generalised lymphadenopathy. A chest computed tomography scan confirmed the presence of mediastinal, hilar and axillary lymphadenopathy, with bilateral pleural effusions. The double stranded DNA antibody (anti-dsDNA) was absent. Subsequently, there was mild renal impairment and a renal biopsy showed lupus nephritis. Anti-dsDNA was positive using an alternative assay. Treatment with prednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil led to considerable clinical improvement. Extensive lymphadenopathy as the first clinical manifestation of SLE is rare and this case also illustrates the variable results obtained from different anti-dsDNA antibody assays.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old man of Caribbean descent presented to his general practitioner with swellings behind his ear. He gave a 3 week history of night sweats, 4 kg weight loss over 3 months, multiple swollen lymph glands, and mild persistent headache. He was referred urgently to hospital.

The patient had no significant previous medical history, nor was there any family history of note. He was not on any medication although he had taken creatine supplements as part of a body building programme in the recent past. He had never smoked and drank alcohol rarely. He had not used any other recreational drugs.

On examination, his temperature was 37.9°C, his pulse rate was 84 beats/min and his blood pressure was normal. He looked comfortable at rest and was not breathless. There was no clubbing, icterus or oedema. Soft, non-tender lymph nodes, 2–3 cm in diameter, were palpable bilaterally in the cervical, axillary, supraclavicular, pre- and post-auricular and inguinal areas. Examination of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems revealed no abnormalities. The liver and spleen were not palpable.

Investigations (normal values in parentheses)

Bloods: urea and electrolyte values were normal:

Haemoglobin 12.2 (14–18) g/dl

Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 78 (80–98) fl

White blood cell count (WBC) 6.7 (3.8–10.8) × 106/l

C reactive protein (CRP) <5 (<5) mg/litre

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 44 (<10) mm in first hour

Albumin 37 (38–50) g/l

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 311 (125–243) U/l

Complement C3 0.45 (0.88–2.01) g/l, C4 0.04 (0.16–0.47) g/l

Serological tests for viral hepatitis B and C were negative. HIV 1 and 2 antibody and P24 antigen tests were negative. Serological tests for cytomegalovirus, toxoplasma and brucella were negative. The Epstein–Barr IgG antibody was present, but the IgM antibody was absent, suggesting that this was not an acute Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection.

No organism was grown on blood culture.

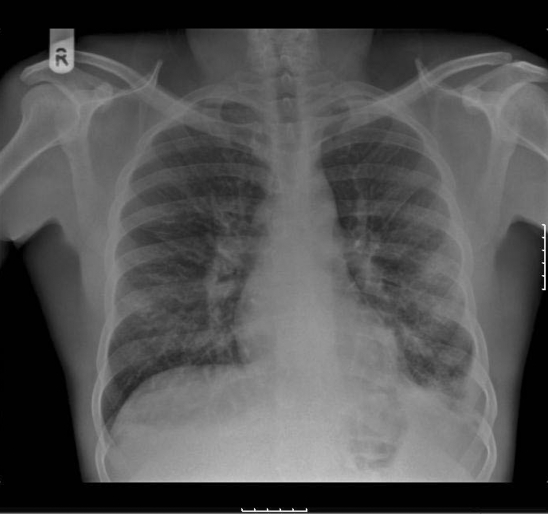

The chest radiograph (fig 1) showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and blunting of the left costophrenic angle.

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph showing bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and blunting of the left costophrenic angle.

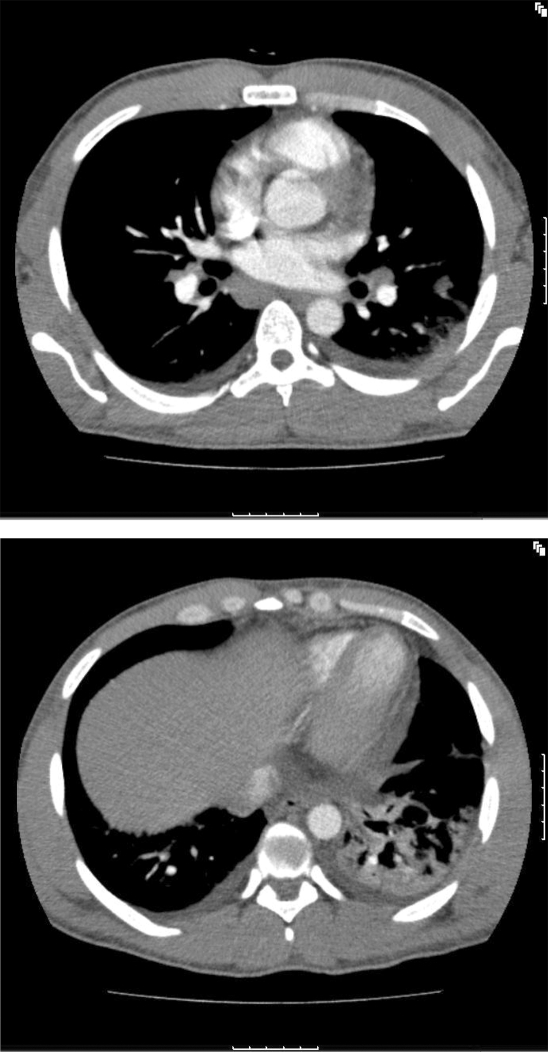

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen (fig 2) was performed and this confirmed mediastinal, hilar and axillary lymphadenopathy as well as small bilateral pleural effusions. There was some consolidation in the left lower lobe and moderate lymphadenopathy was seen in both inguinal regions.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen.

Inguinal node biopsy did not show any evidence of lymphoma. The features were those of reactive hyperplasia only. A bone marrow biopsy was obtained and this also appeared reactive with no evidence of lymphoma or a haematological malignancy. There were no acid fast bacilli on microscopy or other organisms on culture.

At this time, his condition deteriorated with fever, fluid retention, hypoalbuminaemia (dropped from 37 g/l on admission to 21 g/l) and later, worsening renal function with creatinine 147 μmol/l (75–125) and urea 13 mmol/l (2–6.6). Two weeks into his hospital stay, the patient developed a pruritic maculopapular rash over upper limbs. Further investigations revealed a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) at a titre of 1:2560 with a speckled pattern, negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and negative anti-dsDNA. The 24 h urine protein excretion was 3.32 g (0–0.3). The urine dipstick showed blood (++++). The urinary protein/creatinine ratio was raised at 81.05 (0–0.2).

Differential diagnosis

Initially, on clinical grounds, the differential diagnosis included:

systemic viral or bacterial infections

lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD)

sarcoidosis

autoimmune diseases.

The results above and the clinical progression described led to the consideration of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and the patient was referred for a renal biopsy. This revealed mild focal tubular atrophy in association with scarring, and occasional tubules showing hyaline casts. Within the vessels, mild medial and intimal hypertrophy was seen. No vasculitis was evident. There was no evidence of amyloid deposition on Congo red staining. Immunohistochemistry showed widespread mesangial and some capillary loop staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3c, and C9.

These appearances were consistent with lupus nephritis class IVa

Treatment

The patient was treated with methylprednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil. Two days later a considerable clinical improvement was noted and the patient was discharged.

Outcome and follow-up

Two months later he was in complete clinical remission. The laboratory and immunological findings were improving and the dose of steroids was tapered. Six months later he was doing well on maintenance oral corticosteroids.

Discussion

Fever with generalised lymphadenopathy is an extremely common presentation in clinical practice. There are several causes of this, the most common being tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus and infectious mononucleosis.

A degree of lymphadenopathy is frequently a characteristic of established systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but it is rarely the primary presenting feature. Studies have shown the most common sites of lymphadenopathy in SLE include cervical (43%), mesenteric (21%), axillary (18%), and inguinal (17%).1 Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement due to SLE is very rare.2 The presentation of generalised lymphadenopathy with blocks of enlarged retrosternal, mesenteric and retroperitoneal nodes has not been previously described as the initial clinical manifestation of the disease.

Precise differentiation between lupus lymphadenopathy and viral or bacterial infections entails negative serological tests for viruses and negative blood, urine and tissue cultures for bacterial infections. In this case, a careful search for viral and bacterial infections did not reveal an infection.

The absence of granulomata with or without caseation in the inguinal lymph node biopsy, as well as the negative tissue cultures, made tuberculosis and sarcoidosis unlikely.

Palpable lymph nodes in SLE can be bulky enough to mimic lymphoma. However, lymphadenopathy related to lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) requires the existence of neoplastic lymphoid cells in bone marrow or lymph node biopsies. In this case neither bone marrow nor lymph node biopsies uncovered the presence of any neoplastic disorder.

Anti-dsDNA antibodies assay

Anti-double stranded (ds) DNA antibodies are predominantly seen in SLE; however, they are negative in 30% of cases, whereas they appear in only 0.5% of people without SLE.

This patient had lupus nephritis with anti-dsDNA antibodies and rising anti-dsDNA titres along with hypocomplementaemia, particularly a low C3, which frequently points towards active lupus glomerulonephritis.3

His anti-dsDNA was initially negative. However, it was retested only a few days later using a different assay and was found to be positive. Studies have described cases where patients may be negative in one but not another assay.4

The initial assay was performed using a crithidia luciliae immunofluorescence test (CLIF). The second test used an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Research has compared ELISA versus CLIF tests for the effectiveness of anti-dsDNA detection in SLE. ELISA sensitivity was 64% and specificity 95%. For CLIF these values were 39% and 97%, respectively. ELISA therefore has a greater sensitivity than CLIF and thus may explain our findings. Some workers have consequently recommended that ELISA be used in preference to the CLIF test.5,6

Lymphadenopathy and SLE disease severity

Generalised lymphadenopathy is a non-specific sign and is typically not troublesome. It rarely causes immediate danger to the patient. However, it has been found that patients suffering from SLE with lymphadenopathy demonstrate more constitutional symptoms such as tiredness, pyrexia and weight loss, more SLE cutaneous manifestations, higher anti-dsDNA antibodies titres, and diminished complement levels.7 This patient had an early onset of cutaneous symptoms, bilateral pleural effusion, microcytic anaemia, recurrent fever, high titres of ANA, and low complement levels.

Furthermore, among patients with SLE and lymphadenopathy, disease activity calculated using the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) index has been shown to be greater and a higher dose of corticosteroids has been shown to be required to control the disease. Some authors have suggested that lymphadenopathy should be incorporated as one of the clinical findings indicative of disease activity in SLE patients.8

In summary, generalised lymph node enlargement can be caused by active SLE and its presence may be an indication of higher disease severity in these patients. This case demonstrates that in patients with fever and lymphadenopathy, SLE should be considered in the differential diagnosis even if anti-dsDNA antibodies are not found, as the systemic manifestations of lupus can predate, follow, or occur concurrently with generalised lymphadenopathy.

Learning points

Extensive lymphadenopathy as the first clinical manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is rare.

SLE should be considered in patients presenting with lymphadenopathy when other causes cannot be found.

Generalised lymphadenopathy may reflect disease severity in SLE.

Patients may have a negative anti-dsDNA antibody test using one assay, but not when using another.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisner MD, Amory J, Mullaney B, et al. Necrotizing lymphadenitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1996; 26: 477–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal GH, Clough JD, Tubbs RR. Autoimmune and iatrogenic causes of lymphadenopathy. Semin Oncol 1993; 20: 611–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boumpas DT, Fessler BJ, Austin HA, III, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: emerging concepts. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123: 42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 929–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janyapoon K, Jivakanont P. Comparative study of anti-double stranded DNA detection by ELISA and Crithidia luciliae immunofluorescence. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2003; 34: 646–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KH, Han JY, Kim JM, et al. Clinical significance of ELISA positive and immunofluorescence negative anti-dsDNA antibody. Clin Chim Acta 2007; 380: 182–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M. The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Reumatol Port 2008; 33: 402–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapira Y, Weıinberger A, Wysenbeek AJ. Lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Prevalence and relation to disease manifestations. Clin Rheumatol 1996; 15: 335–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]