Abstract

We report a case of a 24-year-old man who presented with a complaint of reduced mouth opening and a burning sensation. On examination, he was clinically diagnosed with oral submucous fibrosis (OSF). Following routine biopsy and histopathological confirmation of OSF, the patient was supplemented with zinc acetate along with vitamin A and was followed up for 4 months. Following treatment the patient reported increased mouth opening and a reduced burning sensation. Histopathologically re-epithelialisation was evident along with the appearance of normal rete pegs. The data for mouth opening, collagen content and epithelial thickness of six other cases similarly treated are also presented, showing a significant increase in mouth opening and epithelial thickness and decrease in collagen content. We propose the use of zinc acetate and vitamin A for the management of OSF.

Background

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is an insidious chronic progressive precancerous condition of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Although it is reported in many parts of the world, including the UK,1 South Africa2 and many southeast Asian countries,3,4 it is mainly prevalent in the Indian subcontinent in all age groups and across all socioeconomic strata.3,4 A large proportion of these precancerous lesions convert to squamous cell carcinoma, the malignant transformation rate being in the order of 7.6%.5

The aetiology of OSF is ill understood, but chewing of the areca nut in isolation or in combination with betel leaf or other tobacco products6,7 has been implicated in the disease. Other factors such as ingestion of chillies, deficiencies of nutrients, trace elements, vitamins, hypersensitivity to various dietary constituents, genetic and immunologic predisposition have also been suggested to be involved in the progression of this disease.5,7–10

The basic change is a fibro-elastic transformation of the connective tissue in the lamina propria preceded by vesicle formation. In its later stages the oral mucous membrane becomes stiff and the patient suffers from trismus or difficulty in opening his or her mouth and a resultant difficulty in eating.11

No satisfactory treatment for OSF has been described, although a wide range of treatment modalities have been proposed. Treatment with steroids, enzymes, micronutrients and minerals, turmeric, IFN-γ and multiple surgical modalities have been tried.

The purpose of the present study is to monitor seven cases before and after administration of zinc acetate along with vitamin A supplement, after motivating the patients to stop chewing areca nut. Following treatment, the patients reported significant increased mouth opening and reduced burning sensation. Re-epithelialisation was clearly evident histologically. Quantitative image analysis noted a significant increase in epithelial thickness following treatment. This case report is intended to create awareness of the beneficial effect of zinc acetate and vitamin A in the treatment of this precancerous condition.

Case presentation

A 24-year-old man presented to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology at the Dr R Ahmed Dental College & Hospital, Kolkata, India, with a complaint of progressive reduction in mouth opening during the previous year, burning sensation on eating spicy food, and occasional vesicle formation on the palate. He denied any other significant medical issue. He gave a history of chewing gutkha (commercially prepared areca nut with smokeless tobacco and other flavouring agents), 7–8 packets per day for a period of 7–8 years, and also smoking bidi.

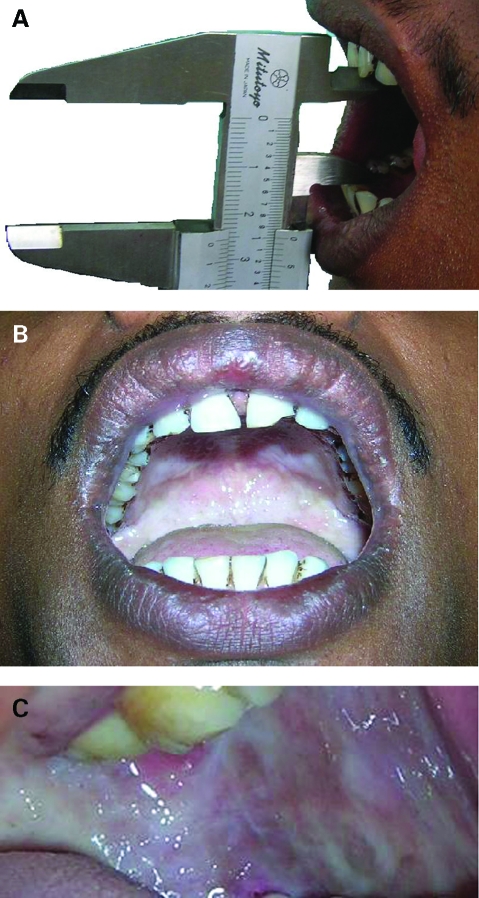

Intraorally, on inspection the maximal inter-incisal distance was noted to be 23 mm (fig 1A). Generalised blanching of the bilateral buccal mucosa was observed. Small vesicles were present on the hard palate (fig 1B, C). On palpation tense fibrous bands were felt in the buccal mucosa. A biopsy was taken from the representative site of the buccal mucosa and histopathological evaluation was done after haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, which revealed the presence of stratified squamous epithelium of variable thickness (5–20 cell layers) along with surface parakeratinisation. The underlying supporting connective tissue showed hyalinisation and homogenisation interspersed with mature spindle shaped fibrocytes and paucity of blood capillaries.

Figure 1.

(A) Maximal inter-incisal distance of 23 mm on Vernier scale. (B) Limited mouth opening with severely blanched palatal mucosa and vesicle formation. (C) Buccal mucosa showing severe blanching, a marble-like appearance, and fibrosis.

Investigations

The patient was subjected to a routine haemogram which was within normal limits and a routine orthopantomogram which did not reveal any other aetiology for trismus.

Treatment

The patient was treated for 4 months with zinc actetate tablets, 50 mg three times daily, and vitamin A 25000 IU, once daily, with regular follow-up at an interval of 1 month.

Outcome and follow-up

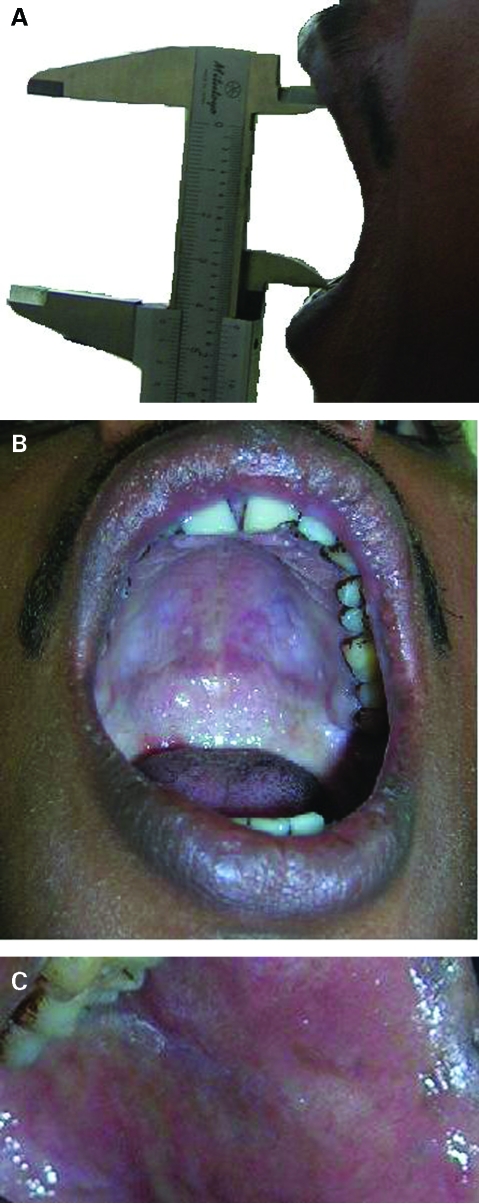

After 2 months of treatment and cessation of oral habits (chewing areca nut and smoking bidi), the patient reported an increased mouth opening of 29 mm with complete relief from burning sensation. On completion of 4 months of treatment the patient was recalled and the inter-incisal distance was now 42 mm (fig 2A). Intraoral examination revealed near normal colour of the mucosa with a few palpable bands on the buccal mucosa. A follow-up incisional biopsy was performed after 4 months and the specimen was obtained from the adjacent area of the previous biopsy site. The section revealed the presence of stratified squamous epithelium (20–25 cell layers) with the presence of rete pegs and surface keratinisation. The underlying connective tissue showed hyalinisation and homogenisation with obliterated blood vessels (fig 3B). The epithelial thickness pre- and post-treatment was measured with the help of Leica QWin plus digital image processing and analysis software (Leica Microsystems Ltd, Switzerland). A significant (p<0.0001, Student’s t test) increase in average epithelial thickness was observed which suggests re-epithelialisation following zinc and vitamin A supplement. The collagen content per unit protein was measured biochemically (Sircol collagen assay kit, UK), and were 95.83 µg/mg protein and 96.84 µg/mg protein at pre- and post-zinc acetate treatment, respectively.

Figure 2.

(A) Post-supplementation maximal inter-incisal distance of 42 mm on Vernier scale. (B) Post-supplementation increased mouth opening with palatal mucosa showing near normal colour with few vesicles along with blanching limited to the lateral aspect of the soft palate. (C) Post-supplementation near normal colour of buccal mucosa with reduced fibrosis.

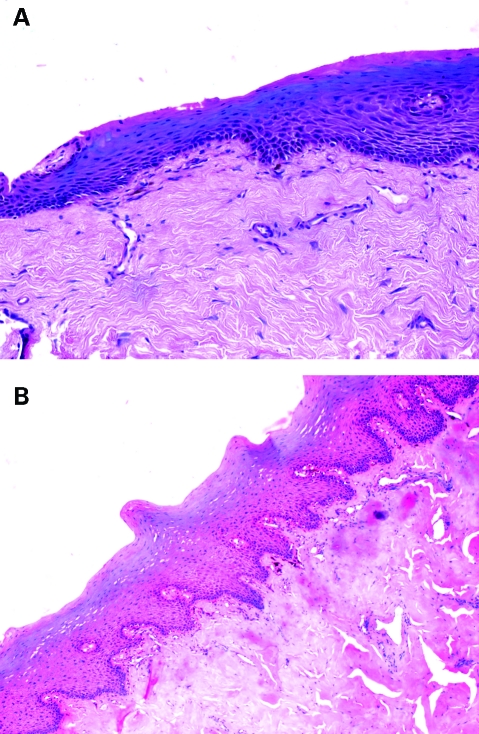

Figure 3.

(A) Pre-treatment microphotograph showing atrophic stratified squamous epithelium with subepithelial hyalinisation and homogenization (haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) ×10). (B) Post-treatment microphotograph showing keratinised stratified squamous epithelium with rete ridges and subepithelial hyalinisation and homogenisation. (H&E ×10).

Discussion

Zinc plays a wide and pivotal biological role in the system of the human body—for example, in DNA synthesis and cell division—and is a constituent of many enzymes, including dehydrogenases and carbonic anhydrase. Our earlier observation noted a pronounced reduction in tissue zinc content of OSF subjects.9 Moreover, zinc is an antagonist of copper; it has been suggested that the copper released from areca nut might upregulate lysyl oxidase activity that leads to increased collagen synthesis and cross-linking. In the present case study, vitamin A, known to stabilise epithelium, was used along with zinc to promote re-epithelialisation and reduce burning sensation in the mouth.

The same treatment protocol was followed for six other OSF cases with similar symptoms. Although, for the case described above, we could not detect any significant alterations in collagen content, in some of the other cases attending the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology at the Dr R Ahmed Dental College & Hospital, the collagen content was found to be reduced: the average collagen content per unit protein of total seven patients, including the case described, was found to be 65.5±21.15 µg/mg protein and 64.4±17.1 µg/mg protein before and after 4 months of supplementation, respectively (table 1). A concomitant increase in average maximal inter-incisal distance (26.5±6.8 mm vs 32.3±9.0 mm) and reduction in burning sensation were noticeable. Measurement of epithelial thickness in H&E stained sections revealed a highly significant increase (p<0.0001, Student’s t test), suggesting re-epithelialisation except in one case (table 2). Further experimentation is needed to study the causal relationship of mouth opening and collagen content in relation to the above treatment in this disease process.

Table 1.

Inter-incisal distance and collagen content of seven oral submucous fibrosis patients pre- and post-treatment with zinc acetate and vitamin A

| Pre-treatment | Inter-incisal distance (mm) | Collagen µg/mg protein | Post- treatment | Inter-incisal distance (mm) | Collagen (µg/mg of protein) |

| Pt 1 | 24 | 55.9 | Pt 1 | 25 | 55.97 |

| Pt 2 | 29 | 86.3 | Pt 2 | 29 | 65.4 |

| Pt 3* | 23 | 95.83 | Pt 3* | 42 | 96.84 |

| Pt 4 | 16 | 32.69 | Pt 4 | 23 | 39.69 |

| Pt 5 | 29 | 55.45 | Pt 5 | 32 | 67.42 |

| Pt 6 | 38 | 71.79 | Pt 6 | 47 | 59.57 |

| Pt 7 | 26 | 60.7 | Pt 7 | 28 | 65.9 |

| Mean | 26.5 | 65.5 | 32.3 | 64.4 | |

| SD | 6.8 | 21.15 | 9.0 | 17.1 |

*This case has been described in this report.

Pt, patient.

Table 2.

Effect of zinc acetate upon the epithelial thickness of oral mucosa of submucous fibrotic patients

| Case ID | Average epithelial thickness | p Values | |||||

| Pre-zinc acetate treatment | Post-zinc acetate treatment | ||||||

| Mean ± SEM | Maximum thickness (µm) | Minimum thickness (µm) | Mean ± SEM | Maximum thickness (µm) | Minimum thickness (µm) | ||

| Pt 1 | 265.1±3.4 | 374.27 | 65.79 | 417.4±8.18 | 598.49 | 154.68 | <0.0001 |

| Pt 2 | 216.2±4.7 | 354.28 | 76.44 | 404.2±7.4 | 863.49 | 109.37 | <0.0001 |

| Pt 3* | 350.37±7.08 | 840.42 | 56.57 | 487.27±8.8 | 863 | 192.52 | <0.0001 |

| Pt 4 | 321±5.69 | 423.75 | 172.67 | 463.31 9.8 | 756.45 | 463.31 | <0.0001 |

| Pt 5 | 298.1±5.6 | 553.9 | 145.97 | 527.5±8.4 | 755.4 | 357.95 | <0.0001 |

| Pt 6 | 205.1±5.3 | 358.34 | 68.1 | 360±6.04 | 577.96 | 165.61 | <0.0001 |

| Pt 7 | 406.8±6.07 | 669.17 | 186.63 | 403.2±8.6 | 942.7 | 110.31 | 0.7265 |

*This case has been described in this report.

Pt, patient.

The only two effective standard approaches to the treatment of OSF are: (1) no treatment with follow-up and behavioural modification; and (2) total excision with soft tissue myocutaneous or free microvascular flaps transposing viable elastic skin. Approaches using injections of steroids, chymotrypsin, hyaluronidase or alcohol, and surgery using mucosal or non-vascularised split thickness grafts, have not only been ineffective but have often exacerbated the condition, with added scar tissue.12 In this context, zinc acetate and vitamin A supplementation had a positive effect in the cases under study; however, the treatment needs to be coupled with cessation of oral habits such as chewing areca nut for improved management.

Learning points

Areca nut or a combination of areca nut with smokeless tobacco and other flavouring agents plays a crucial role in the aetiology of oral submucous fibrosis.

Cessation of oral habits along with zinc and vitamin A supplementation resulted in a reduction in clinical symptoms.

A significant increase in average epithelial thickness was observed post-supplementation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canniff JP, Harvey W, Harris M. Oral submucous fibrosis: its pathogenesis and management. Br Dent J 1986; 160: 429–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seedat HA, VanWyk CW. Betel-nut chewing and submucous fibrosis in Durban. S Afr Med J 1988; 74: 568–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maher R, Lee AJ, Warnakulasuriya K, et al. Role of areca nut in the causation of oral submucous fibrosis: acase-control study in Pakistan. J Oral Pathol Med 1994; 23: 65–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zain RB, Ikeda N, Razak IA, et al. A national epidemiological survey of oral mucosal lesions in Malaysia. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997; 25: 377–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aziz SR. Oral submucous fibrosis: an unusual disease. J N J Dent Assoc 1997; 68: 17–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. Oral pathology: clinical pathologic correlations. London: WB Saunders, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao PH, Lee TL, Yang LC, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli gene mutation and decreased wild-type p53 protein expression in oral submucous fibrosis: a preliminary investigation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001; 92: 202–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Wyk CW, Grobler-Rabie AF, Martell RW, et al. HLA-antigens in oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med 1994; 23: 23–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul RR, Chatterjee J, Das AK, et al. Altered elemental profile as indicator of homeostatic imbalance in pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis. Biol Trace Elem Res 2002; 87: 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul RR, Chatterjee J, Das AK, et al. Zinc and iron as bioindicators of precancerous nature of oral submucous fibrosis. Biol Trace Elem Res 1996; 54: 213–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral surgery 1966; 22: 764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx RE, Stern D, eds. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, a rationale for diagnosis and treatment. Germany: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc, 2003: 317–9 [Google Scholar]