Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Skeletal complications are a major cause of morbidity in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. These analyses were designed to identify the variables associated with a greater risk of skeletal complications.

METHODS

The 643 subjects in this report were participants in a randomized placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the effects of zoledronic acid on the incidence of skeletal-related events. All subjects had bone metastases and disease progression despite medical or surgical castration. The relationships between the baseline covariates and the time to the first skeletal-related event were assessed by Cox proportional hazard analyses. The serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP) and urinary N-telopeptide level was assessed as a representative specific marker of osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity, respectively. The other covariates included in the model were age, cancer duration, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, analgesic use, and prostate-specific antigen, hemoglobin, and lactate dehydrogenase levels.

RESULTS

Elevated BAP levels were consistently associated with a greater risk of adverse skeletal outcomes. Elevated BAP was significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event on multivariate analyses of the entire study population (relative risk 1.84, 95% confidence interval 1.40 to 2.43; P <0.001) and in subset analyses of the placebo and zoledronic acid groups. Elevated BAP levels were also consistently associated with adverse skeletal outcomes on multivariate analyses of the time to radiotherapy and pathologic fracture, the most common types of skeletal-related events in the study population. No other baseline variable was consistently associated with the risk of adverse skeletal outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study have shown that elevated serum BAP levels are associated with a greater risk of adverse skeletal outcomes in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer and bone metastases.

Prostate cancer is the most common solid tumor in men worldwide. In 2005, approximately 232,090 new cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed and 30,350 prostate cancer deaths occurred in the United States.1

Skeletal complications are a major cause of morbidity in men with metastatic prostate cancer. Bone metastases cause pain, pathologic fractures, spinal cord compression, and ineffective hematopoiesis.2 Disease-related skeletal complications are associated with shorter overall survival3 and a decreased quality of life.4 Despite the importance of skeletal complications in this setting, however, little is known about the factors associated with a greater risk of skeletal complications.

The objective of this study was to identify the clinical and laboratory variables associated with a greater risk of skeletal complications in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Data from a multicenter randomized controlled trial5 were used to examine the relationships between the baseline variables, including biochemical markers of bone metabolism, and the time to the first skeletal-related event.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Population

We used data from a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial designed to evaluate the effect of zoledronic acid on the incidence of skeletal complications in men with metastatic prostate cancer.5 The study included 643 men with histologically confirmed prostate cancer, bone metastases, and disease progression despite medical or surgical castration. All subjects had an Eastern Cooperative Group performance status of 2 or less, serum testosterone less than 50 ng/dL, corrected serum calcium level of 8.0 mg/dL or less, and serum creatinine of 3.0 mg/dL or less. Men with who had undergone prior cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 3 months or had severe cardiovascular disease were excluded. All subjects were enrolled from June 1998 to January 2001, and were followed up for up to 24 months.

Statistical Analysis

The primary study outcome for these analyses was the time to the first skeletal-related event. Skeletal-related events were prospectively defined as the need for radiotherapy to bone, pathologic bone fractures, the need for surgery to bone, spinal cord compression, or a change in antineoplastic therapy to treat bone pain. Subjects who withdrew from, or completed, the study before a skeletal-related event occurred were censored.

Univariate Cox regression models were fit for the time to the first skeletal-related event using each covariate as a single explanatory variable. Next, multivariate models were fit using all explanatory variables to identify those that were independently predictive.6,7 Stepwise backward elimination was performed to determine the simplest multivariate model; only terms remaining significant at the 5% level were retained in the reduced models. To assess the sensitivity of the findings to the coding of the bone marker variables, three sets of models were considered, with bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP) and N-telopeptide (NTx) summarized as dichotomous (less than the median or the median or greater) variables, quartiles, or continuous variables. All Cox regression models were stratified by the presence of bone metastases at the initial prostate cancer diagnosis (yes or no) and the treatment assignment (placebo group, zoledronic acid 4-mg group, or zoledronic acid 8-mg group). Diagnostic tests of the model assumptions were performed according to Schoenfeld residuals.8 Cumulative incidence function plots were used to estimate the probability of a skeletal-related event as a function of the baseline marker values because of the competing risk of death.6

Because of the significant associations with overall survival in large multivariate analyses of men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer,9,10 age, Eastern Cooperative Group performance status, hemoglobin, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) were included as covariates in the Cox regression analyses. Bone pain and a requirement for narcotic analgesics were also included as measures of symptomatic metastatic disease. Serum BAP and urinary NTx were included in the analyses as representative specific markers of osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity, respectively. Prior skeletal-related events, cancer duration, and the presence of lymph node metastases were also included as covariates in the analyses.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All the men had bone metastases at study entry. Of the 643 men, 278 (43%) had bone metastases at their initial diagnosis of prostate cancer, and 137 (21.4%) required narcotic analgesics for pain.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 643)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |

| Mean | 72 ± 8 |

| Median | 72 |

| Range | 37–90 |

| Cancer duration (yr) | |

| Mean | 5.5 ± 3.7 |

| Median | 4.8 |

| Range | 0.1–23.6 |

| Lymph node metastases (n) | 37 (6) |

| ECOG performance status ≥ 1 (n) | 365 (57) |

| Bone pain (BPI ≥2) (n) | 301 (52) |

| Analgesic use (n) | 396 (62) |

| Prior SRE (n) | 215 (34) |

| Creatinine (creatinine ≥1.4 mg/dL) (n) | 122 (19) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | |

| Mean | 12.0 ± 15.2 |

| Median | 4.3 |

| Range | 2.01–50.0 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |

| Mean | 12.5 ± 1.6 |

| Median | 12.7 |

| Range | 5.4–16.9 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | |

| Mean | 285 ± 208 |

| Median | 211.0 |

| Range | 13.0–2229.0 |

| PSA (ng/mL) | |

| Mean | 282 ± 839 |

| Median | 77.3 |

| Range | 0.2–9124.0 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |

| Mean | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| Median | 1.1 |

| Range | 0.6–4.5 |

| Urinary NTx (nmol/mmol creatinine) | |

| Mean | 178 ± 279 |

| Median | 89.0 |

| Range | 2.0–2611.0 |

| Serum BAP (U/L) | |

| Mean | 559 ± 909 |

| Median | 267.5 |

| Range | 44.0–10640.0 |

ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Group; BPI = bone pain index; SRE = skeletal-related events; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; NTx = N-telopeptide; BAP = bone-specific alkaline phosphatase.

Data presented as mean = standard deviation or numbers of patients, with percentages in parentheses.

Cox Proportional Hazard Analyses

The relationships between the baseline characteristics and the time to the first skeletal-related event were assessed by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses. On univariate Cox regression analyses, narcotic analgesic use, a prior skeletal-related event, and greater levels of LDH, PSA, NTx, and BAP were significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event (Table 2). Greater urinary NTx and serum BAP levels were significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event, whether these markers were summarized as dichotomous (less than the median or the median or greater) variables, quartiles, or continuous variables.

Table 2.

Univariate Cox regression analyses for time to first SRE

| Variable | Relative Risk | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.66 |

| Cancer duration (yr) | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.37 |

| Lymph node metastases (yes) | 0.69 | 0.37–1.28 | 0.24 |

| ECOG (≥1) | 1.18 | 0.91–1.54 | 0.21 |

| Bone pain (BPI ≥2) | 1.22 | 0.94–1.59 | 0.13 |

| Narcotic analgesic use (yes) | 1.53 | 1.10–2.13 | 0.01 |

| Prior SRE (yes) | 1.39 | 1.06–1.83 | 0.02 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.07 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.94 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.16 |

| LDH (>454 U/L) | 2.01 | 1.27–3.18 | 0.003 |

| Log PSA (log ng/mL) | 1.17 | 1.08–1.26 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (≥1.4 mg/dL) | 0.87 | 0.60–1.26 | 0.46 |

| NTx (NTx/CR) | |||

| <89.0 | — | — | — |

| ≥89.0 | 1.73 | 1.33–2.24 | <0.001 |

| <54.5 | — | — | — |

| ≥54.5 to <89.0 | 1.28 | 0.88–1.84 | 0.20 |

| ≥89.0 to <180.5 | 1.77 | 1.22–2.55 | 0.003 |

| ≥180.5 | 2.12 | 1.47–3.06 | <0.001 |

| NTx (50 nmol/mmol creatinine increase) | 1.05 | 1.02–1.07 | <0.001 |

| BAP | |||

| <267.50 | — | — | — |

| ≥267.50 | 2.04 | 1.56–2.65 | <0.001 |

| <150.25 | — | — | — |

| ≥150.25 to <267.50 | 1.53 | 1.04–2.24 | 0.03 |

| ≥267.50 to <529.75 | 2.56 | 1.76–3.73 | <0.001 |

| ≥529.75 | 2.48 | 1.68–3.67 | <0.001 |

| BAP (200 U/L increase) | 1.05 | 1.02–1.07 | <0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; CR = creatinine; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Models stratified by bone metastasis status at initial diagnosis (yes vs. no) and treatment assignment (placebo group, zoledronic acid 4 mg, or zoledronic acid 8 mg).

After controlling for the other variables in the full multivariate models, greater LDH, PSA, and BAP levels were consistently associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event (Table 3). Greater serum BAP levels were significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event in the multivariate models when the bone markers were summarized as dichotomous variables, quartiles, or continuous variables. In contrast, the NTx levels were not significantly associated with the time to the first skeletal-related event on multivariate analyses. Greater LDH, PSA, and BAP levels were retained as significant predictors of a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event in the reduced multivariate models (data not shown). A prior skeletal-related event was also significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event in the reduced multivariate models.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression analyses for time to first SRE, full model

| Variable | Marker Assessment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichotomous |

Quartiles |

Continuous |

|||||||

| RR | 95% CI | P Value | RR | 95% CI | P Value | RR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.66 |

| Cancer duration (yr) | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.47 |

| Lymph node metastases (yes) | 0.70 | 0.37–1.31 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.37–1.30 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.33–1.17 | 0.14 |

| ECOG (≥1) | 1.08 | 0.81–1.43 | 0.61 | 1.07 | 0.81–1.42 | 0.62 | 1.10 | 0.83–1.45 | 0.51 |

| Bone pain (BPI ≥2) | 0.96 | 0.71–1.28 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.71–1.27 | 0.72 | 0.99 | 0.74–1.33 | 0.96 |

| Narcotic analgesic use (yes) | 1.14 | 0.79–1.65 | 0.48 | 1.18 | 0.82–1.72 | 0.38 | 1.15 | 0.79–1.66 | 0.47 |

| Prior SRE (yes) | 1.28 | 0.96–1.72 | 0.09 | 1.29 | 0.96–1.72 | 0.09 | 1.30 | 0.97–1.73 | 0.08 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.54 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 1.01 | 0.91–1.11 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.92–1.13 | 0.75 |

| LDH (>454 U/L) | 1.82 | 1.09–3.04 | 0.02 | 1.88 | 1.12–3.14 | 0.02 | 1.83 | 1.09–3.05 | 0.02 |

| Log PSA (Log ng/mL) | 1.09 | 0.99–1.19 | 0.06 | 1.10 | 1.01–1.21 | 0.04 | 1.12 | 1.03–1.22 | 0.01 |

| Creatinine ≥1.4 mg/dL | 0.85 | 0.58–1.25 | 0.42 | 0.85 | 0.58–1.25 | 0.41 | 0.87 | 0.59–1.28 | 0.49 |

| NTx (NTx/CR) | |||||||||

| ≥89.0 | 1.03 | 0.73–1.45 | 0.86 | ||||||

| <54.5 | |||||||||

| ≥54.5 to <89.0 | 1.10 | 0.75–1.61 | 0.62 | ||||||

| ≥89.0 to <180.5 | 1.07 | 0.70–1.62 | 0.76 | ||||||

| ≥180.5 | 1.02 | 0.61–1.69 | 0.95 | ||||||

| NTx (50 nmol/mmol creatinine increase) | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.32 | ||||||

| BAP | |||||||||

| ≥267.50 | 1.81 | 1.30–2.530 | <0.001 | ||||||

| <150.25 | |||||||||

| ≥150.25 to <267.50 | 1.55 | 1.04–2.32 | 0.03 | ||||||

| ≥267.50 to <529.75 | 2.50 | 1.62–3.84 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≥529.75 | 2.04 | 1.20–3.46 | 0.008 | ||||||

| BAP (200 U/L increase) | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 0.07 | ||||||

In other analyses restricted to subjects in the placebo group, greater levels of LDH (relative risk 3.02, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.34 to 6.79, P = 0.008), PSA (relative risk 1.16, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.34, P = 0.04), and BAP (relative risk 1.70, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.68, P = 0.02) were significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event in the reduced multivariate models. On analyses restricted to men in the zoledronic acid group, elevated BAP was also significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event in the reduced multivariate models (relative risk 2.05, 95% CI 1.47 to 2.86, P <0.001). Prior skeletal-related events and the levels of LDH and PSA were not significantly associated with the time to the first skeletal-related event in the multivariate analyses restricted to the zoledronic acid group.

We conducted additional multivariate analyses for the time to the first pathologic fracture and the time to radiotherapy to bone, the two most common types of skeletal-related events in the study. In these analyses, greater levels of BAP were significantly associated with a shorter time to the first pathologic fracture (relative risk 1.60, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.37, P = 0.02) and the time to radiotherapy to bone (relative risk 2.07, 95% CI 1.50 to 2.85, P <0.001).

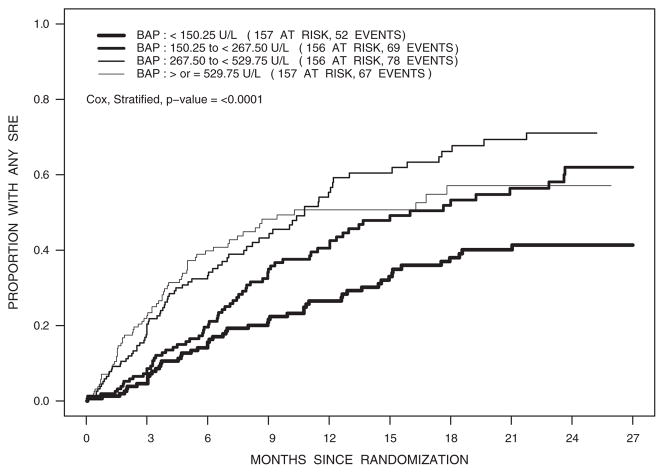

To illustrate the clinical utility of serum BAP levels, the only baseline variable consistently associated with adverse skeletal outcomes in each of these analyses, we constructed cumulative incidence plots of the time to the first skeletal-related event according to the marker quartiles (Fig. 1). Consistent with the results of the Cox proportion hazard analyses, the time to the first skeletal-related event was significantly shorter with greater BAP levels (P <0.001). At 1 year, for example, the cumulative incidence of skeletal-related events was approximately twofold greater for men in the greatest versus lowest BAP quartile (50.7% versus 26.5%).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence plots for skeletal-related events (SRE) according to quartiles of serum BAP.

COMMENT

Using data from a large multicenter, randomized, controlled trial, we observed that greater serum BAP levels are consistently associated with a greater risk of adverse skeletal outcomes in men with hormone-refractory prostate and bone metastases. Elevated BAP levels were significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event on multivariate analyses of the entire study population. Elevated BAP levels were also significantly associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event in subset analyses of the placebo and zoledronic acid groups. Elevated BAP levels were associated with adverse skeletal outcomes on multivariate analyses of the time to radiotherapy and pathologic fracture, the two most common types of skeletal-related events in the study population. No other baseline variable was consistently associated with the risk of adverse skeletal outcomes in each of these analyses.

Few other studies have assessed the factors associated with skeletal complications in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. In a single institution series of 200 men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer, baseline performance status, bone pain, disease extent in bone as assessed by radiographic imaging and serum BAP and urinary NTx measurement were associated with the risk of skeletal complications.11 On multivariate analyses, only bone pain and disease extent in bone were associated with the risk of skeletal complications. Disease extent was also associated with the risk of occult spinal cord compression in a series of 68 men with metastatic prostate cancer.12 Information about disease extent by radiographic imaging was not available for our analyses. However, the serum BAP level correlates closely with the extent of skeletal involvement,13–15 and the significant association between serum BAP and the time to first skeletal-related event likely reflects the extent of skeletal metastases.

Tissue-specific isoenzymes of alkaline phosphatase are present in bone, liver, intestine, kidney, and leukocytes. Serum total alkaline phosphatase mainly reflects liver and bone isoenzymes in normal adults.16 In men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer and bone metastases, the serum total alkaline phosphatase and BAP levels are highlycorrelated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.986, 95% CI 0.982 to 0.987, P < 0.0001),17 indicating that serum total alkaline phosphatase primarily reflects bone-specific isoenzyme in this setting. As expected, elevated serum levels of either total alkaline phosphatase or BAP were independently associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event (data not shown). Taken together, these observations suggest that total alkaline phosphatase is an appropriate surrogate for the bone-specific isoform to assess the risk of skeletal complications for most clinical and research purposes in men with metastatic prostate cancer.

In our univariate analyses of all 643 subjects, elevated serum BAP and urinary NTx levels were associated with a shorter time to the first skeletal-related event. This finding is consistent with published univariate analyses of 203 subjects in the placebo group18 and 440 subjects in the zoledronic acid groups19 from the same randomized controlled trial. Baseline levels of urinary NTx did not remain independently associated with the risk of skeletal-related events, however, when controlling for other baseline variables in either the entire study cohort or subjects assigned to the placebo group. In the prospective clinical trial, serum BAP and NTx were measured at baseline, 1 and 3 months, and every 3 months thereafter. The univariate published analyses of subjects in the placebo and zoledronic acid groups evaluated the relationships between the baseline and most recent BAP and NTx levels. In contrast, our multivariate analyses were restricted to the baseline marker levels. We limited the analyses to the baseline BAP and NTx values to allow unbiased comparison with the other variables that were not serially assessed during the study. Because zoledronic acid significantly decreases serum BAP and urinary NTx, we also limited the analyses to the baseline values to allow the inclusion of subjects in the zoledronic acid groups without the potential confounding effects of treatment on the analyses. Taken together, these results suggest that other covariates in the multivariate model explain the previously reported association between NTx and skeletal-related events. Our observations did not diminish the value of urinary NTx or other markers of osteoclastic activity for monitoring the efficacy of bisphosphonate treatment in patients with cancer.

Our study had limitations. We used serum BAP and urinary NTx as representative markers of osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. Although other specific markers of bone metabolism have similar operating characteristics, different results might be observed using other markers of osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. The men in the study cohort received additional treatment, including secondary hormonal therapy and/or chemotherapy at physician discretion. This feature of the study cohort increased the generalizability of our observations. Because detailed information about secondary hormonal therapy and chemotherapy was not collected, however, we could not assess the effects of these other treatments on the risk of skeletal complications.

CONCLUSIONS

Elevated levels of BAP are associated with a greater risk of adverse skeletal outcomes in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer and bone metastases. This observation could help inform the design of future clinical trials of bone-targeted therapy in men with prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Novartis Oncology and the W. Bradford Ingalls Foundation.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinski J, Dorff TB. Prostate cancer metastases to bone: patho-physiology, pain management, and the promise of targeted therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:932–940. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oefelein MG, Ricchiuti V, Conrad W, et al. Skeletal fractures negatively correlate with overall survival in men with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2002;168:1005–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groot MT, Boeken Kruger CG, Pelger RC, et al. Costs of prostate cancer, metastatic to the bone, in the Netherlands. Eur Urol. 2003;43:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1458–1468. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalbfleisch J, Prentice R. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawless J. Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grambsch PM. Goodness-of-fit and diagnostics for proportional hazards regression models. Cancer Treat Res. 1995;75:95–112. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2009-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smaletz O, Scher HI, Small EJ, et al. Nomogram for overall survival of patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer after castration. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3972–3982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halabi S, Small EJ, Kantoff PW, et al. Prognostic model for predicting survival in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1232–1237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berruti A, Tucci M, Mosca A, et al. Predictive factors for skeletal complications in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients with metastatic bone disease. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:633–638. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayley A, Milosevic M, Blend R, et al. A prospective study of factors predicting clinically occult spinal cord compression in patients with metastatic prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:303–310. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010715)92:2<303::aid-cncr1323>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berruti A, Dogliotti L, Gorzegno G, et al. Differential patterns of bone turnover in relation to bone pain and disease extent in bone in cancer patients with skeletal metastases. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1240–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontana A, Delmas PD. Markers of bone turnover in bone metastases. Cancer. 2000;88:2952–2960. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12+<2952::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garnero P. Markers of bone turnover in prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:187–196. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Posen S, Doherty E. The measurement of serum alkaline phosphatase in clinical medicine. Adv Clin Chem. 1981;22:163–245. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(08)60048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook RJ, Coleman R, Brown J, et al. Markers of bone metabolism and survival in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3361–3367. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown JE, Cook RJ, Major P, et al. Bone turnover markers as predictors of skeletal complications in prostate cancer, lung cancer, and other solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:59–69. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman RE, Major P, Lipton A, et al. Predictive value of bone resorption and formation markers in cancer patients with bone metastases receiving the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4925–4935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]