Abstract

Aim/hypothesis

Neonatal beta cells lack glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and are thus functionally immature. We hypothesised that this lack of glucose responsiveness results from a generalised low expression of genes characteristic of mature functional beta cells. Important glucose-responsive transcription factors, Mafa and Pdx1, regulate genes involved in insulin synthesis and secretion, and have been implicated in late beta cell development. The aim of this study was to assess whether Mafa and/or Pdx1 regulates the postnatal functional maturation of beta cells.

Methods

By quantitative PCR we evaluated expression of these and other beta cell genes over the first month compared with adult. After infection with adenovirus expressing MAFA, Pdx1 or green fluorescent protein (Gfp), P2 rat islets were evaluated by RT-PCR and insulin secretion with static incubation and reverse haemolytic plaque assay (RHPA).

Results

At P2 most beta cell genes were expressed at about 10% of adult, but by P7 Pdx1 and Neurod1 no longer differ from adult; by contrast, Mafa expression remained significantly lower than adult through P21. Overexpression of Pdx1 increased Mafa, Neurod1, glucokinase (Gck) mRNA and insulin content but failed to enhance glucose responsiveness. Similar overexpression of MAFA resulted in increased Neurod1, Nkx6-1, Gck and Glp1r mRNAs and no change in insulin content but, importantly, acquisition of glucose-responsive insulin secretion. Both the percentage of secreting beta cells and the amount of insulin secreted per beta cell increased, approaching that of adult beta cells.

Conclusions/interpretation

In the process of functional maturation acquiring glucose-responsive insulin secretion, neonatal beta cells undergo a coordinated gene expression programme in which Mafa plays a crucial role.

Keywords: Beta cell development, Insulin secretion, MAFA, Maturation

Introduction

Currently insulin-positive cells produced in vitro lack glucose-responsive insulin secretion and so must be considered functionally immature [1, 2]. Similarly, fetal and neonatal beta cells lack glucose responsiveness [3–5], providing a model to study the postnatal acquisition of glucose responsiveness. The molecular basis of this functional immaturity has been suggested as impaired function of calcium channels [6], of stimulus-secretion coupling [7, 8], or of the mitochondrial NADH shuttles [9]. However, based on gene profiling on laser-capture microdissected beta-cell-enriched cores of islets from neonatal (P1) and adult rats, we hypothesised that the lack of glucose responsiveness in neonatal islets was probably due to a generalised immaturity of the specialised metabolism of pancreatic beta cells. A number of genes, including key metabolic genes, had very low expression in neonatal beta cells, but there were few differences in genes for exocytotic machinery [10].

With many genes differentially expressed in the neonatal beta cell, a possible role of differential expression of key beta-cell-enriched transcription factors must be considered. Pdx1 and Mafa are most likely to be involved in the maturation process, because their expression is turned on after that of insulin during development [11]. Target genes of both Pdx1 [12] and Mafa [13] have been reported, with many exocytotic genes regulated by Pdx1, and genes of insulin synthesis and secretion regulated by Mafa. Pdx1 is crucial in pancreas formation [14, 15] and beta cell differentiation [16–18]. A role for Mafa in maturation is supported by: (1) several of its putative target genes (insulin 2, prohormone convertase 1/3 (Pcsk1) and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (Glp1r) [13]) have reduced expression in neonatal beta cells [10]; (2) the switch from MAFB+MAFA−INS+ to MAFB−MAFA+INS+ is a late stage event in beta cell differentiation [11] (INS, insulin; MAFA, v-Maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homologue A [avian]; MAFB, v-Maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homologue B [avian]); and (3) Mafa-deficient mice appearing normal at birth but postnatally developing impaired secretagogue-stimulated insulin secretion and glucose intolerance [19]. In addition, insulin-expressing MAFB+ cells derived from human embryonic stem cells lacked glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in vitro [1, 20] but acquired both glucose responsiveness and MAFA production after transplantation into mice [2].

To assess whether maturation of neonatal beta cells into glucose-responsive insulin secreting cells is regulated by Pdx1 and/or Mafa, we characterised their expression and that of other key beta cell genes during the first 4 weeks of postnatal life. We found expression of Mafa, Pdx1 and many other beta cell genes expressed at only about 10% of adult levels in the first postnatal week, with increasing but differing patterns until P28. We hypothesised that enhancing the expression levels of these factors in neonatal beta cells could drive the acquisition of glucose-responsive insulin secretion. We showed that adenoviral-mediated overexpression of either MAFA or Pdx1 in P2 islet cells significantly enhanced their maturation. However, overexpressed Pdx1 failed to increase glucose responsiveness, whereas MAFA increased glucose responsiveness with increased percentage of secreting cells and increased insulin secretion by individual cells.

Methods

Animals

Female Sprague–Dawley rats with various aged litters (P0 as day of birth) (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA) were kept under conventional conditions with free access to water and food. Islets were isolated from P2, P7, P9, P11, P13, P15, P21 and P28 and adult 10-week-old rats by collagenase digestion [21] and after an overnight culture in RPMI 1640 (11 mmol/l glucose, 10% FBS) handpicked to ensure high purity. For each P2 or P7 sample, islets from 10 animals were pooled; for P9–P28, islets from two to three animals; for adults, islets from one animal. For each age, there were three to six samples. For immunostaining, pancreases were excised and either fixed for 2 h in 4% paraformaldehyde for paraffin embedding or embedded in optimal cutting tissue compound (OCT) medium (Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA, USA) and processed for frozen blocks. All animal procedures were approved by the Joslin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Adenovirus infection

Human MAFA coding sequence (cds) was used to generate Adeno-CMV-hMAFA-IRES-green fluorescent protein (Gfp) (Ad-MAFA) based on pShuttle vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA); adenovirus containing the coding sequence for Pdx1 (Ad-Pdx1) was a kind gift from D. Melton (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA) [22]; Adeno-CMV-IRES-Gfp (Ad-Gfp) was used as control. Neonatal and adult islets were partially dispersed, plated on gelatin-treated dishes, and infected overnight with adenovirus in RPMI 1640 (11 mmol/l glucose, 10% FBS), washed and cultured for 3–5 days in RPMI (20 mmol/l glucose, 10% FBS). The high glucose concentration permits the strongest Mafa and Pdx1 transcriptional effects. After 72 h, samples were tested for secretion, extracted for RNA or fixed for immunostaining.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using PicoRNA extraction kit (Arcturus, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed to obtain cDNA (SuperScript reverse transcriptase; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR with SYBR green detection was performed using specific primers (Electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). Samples were normalised to a control gene (S25), and the comparative threshold cycle method used to calculate gene expression levels. Adenoviral-hMAFA mRNA was determined by comparison of two different sets of primers: one recognising the cds of both endogenous (rat) and adenoinfected (human) MAFA, and the other recognising the 3′ untranslated (UTR) sequence of Mafa only present in the endogenous transcript.

Immunostaining

Paraffin sections or formalin-fixed cells in dishes were incubated overnight with rabbit anti-MAFA (1:500 [11]); rabbit anti-glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) (1:1,000; a kind gift from J. Habener and T. Kieffer, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA [23]) or rabbit anti-prohormone convertase type 1 (PCSK1) (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C followed by a biotin–streptavidin system conjugated to Alexa fluor 488 (1:200) for GLP1R and PCSK1 and to VIP (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) for MAFA. In addition, sections were incubated with guinea pig anti-insulin (1:200; Linco, Billerica, MA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature, followed by FITC or Texas Red anti-guinea pig IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Westgrove, PA, USA). For quantification of nuclear MAFA, frozen sections were incubated with rabbit anti-MAFA antibody (1:1,500; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA), followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and streptavidin-conjugated Alexa fluor 488 antibody (Invitrogen). These sections were also immunostained for insulin; DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Images for each antigen were taken in confocal mode on a Zeiss LSM 410 or 710 microscope at the same settings and handled similarly in Adobe Photoshop across all images; at least three animals per age were examined.

Insulin-positive cells were identified and counted as high, low or not detected for MAFA or pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) nuclear staining on images based on the relative intensity of the fluorescent signal. Between 20 and 82 different islets were sampled for each age; values from individual animals (three to five) were averaged for each age.

Insulin secretion in vitro

Insulin secretion was measured in static conditions after 5 days culture in P2 Ad-Gfp, P2 Ad-MAFA, P2 Ad-Pdx1, adult Ad-Gfp, and adult and P2 untreated islets by sequential incubation in 2.6 mmol/l and 16.8 mmol/l glucose in KRB (16 mmol/l HEPES and 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4) as previously described [24]. Supernatant fractions and cells were frozen until assayed with Insulin Rat (EIA) kit (ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA).

Alternatively, we measured insulin secretion of single beta cells using the reverse haemolytic plaque assay (RHPA) as previously described [25]. After 5 days culture, cells were completely dispersed and mixed with 18% suspension of protein A-coated sheep erythrocytes and introduced into a poly-l-lysine-coated glass Cunningham chamber. They were challenged for 2 h with 2.6 or 16.8 mmol/l glucose in KRB in the presence of guinea pig anti-insulin antiserum (1:40, generated in our laboratory) and after 30 min incubation with guinea pig complement (1:40; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Secreted insulin was revealed as haemolytic plaques around secreting cells. A secretion index (average plaque area multiplied by the percentage of plaque-forming cells) indicated the overall secretory activity of beta cells under a given condition.

Western blot analysis

Total protein extracts of sonicated islets (20 µg) were boiled, resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes and probed with either MAFA (1:2,000 [11]) or PDX-1 (1:1,000; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, USA) antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. Primary antibodies were diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 (TBST). Membranes were washed in TBST, incubated with either anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and processed using either chemiluminescence SuperSignal West Dura or West Dura Femto reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Data analysis

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. For statistical analysis, unpaired Student’s t test was used. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of beta cell transcription factors during the postnatal period

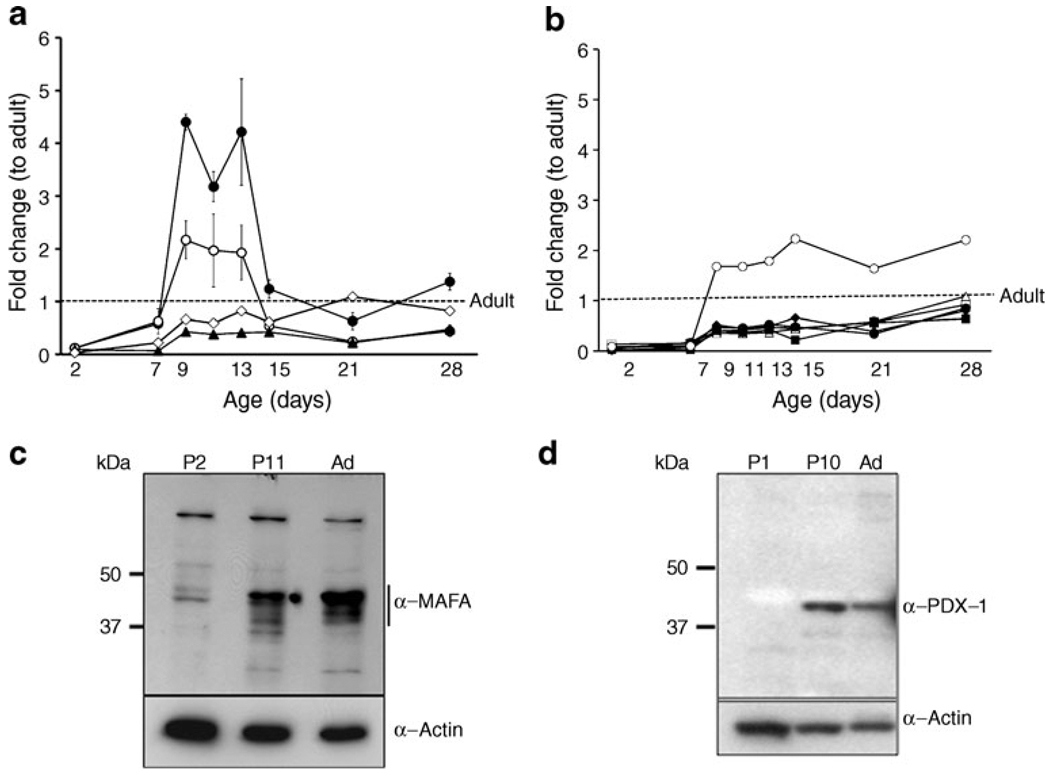

We had previously found by microarray analysis the reduced expression of many key beta cell genes in neonatal beta cells, suggesting that regulated expression of transcription factors may drive beta cell maturation. To examine the expression of these factors, quantitative RT-PCR was performed on neonatal islets isolated over the first postnatal month. Key beta cell transcription factors (Fig. 1a) had very low (3–12%) expression at P2, with sharp increases between P7 and P9 (Table 1). By P7 both Pdx1 and Neurod1 mRNA levels no longer differed from adult levels and from P9 to P13 were transiently higher than adult (Pdx1 was increased in all samples but did not reach significance). Nkx6-1 mRNA was expressed at levels lower than adult only through P7. Unexpectedly Mafb mRNA, which is expressed in alpha cells and immature beta cells, did not differ from adult even at P2 and rose to 15-fold higher than adult by P9, remaining significantly elevated even at P28 (ESM Fig. 1). By contrast, Mafa expression increased from 7% at P7 to 43% of adult at P9 but remained significantly lower than adult until P28.

Fig. 1.

Expression pattern of beta cell transcription factors during the first postnatal month. a Beta cell transcription factors Neurod1 (black circle), Pdx1 (white circle), Mafa (black triangle), Nkx6-1 (white diamond); (b) other key genes: Glp1r (black diamond), Pc (white square), Pcsk1 (white triangle), insulin (black circle), Glut2 (black square) and Gck (white circle) mRNA show different patterns of expression over the neonatal period as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Data expressed as fold change with respect to adult using S25 as internal control gene. Mean ± SEM, n=4–6 isolated samples per age, each pooled from three to ten animals. The same samples were analysed in Fig. 1a, b and ESM Fig. 1. Quantification of the beta cell proportion showed isolated neonatal islets did not significantly differ from adult in % beta cell [10]. Only P11 had significantly lower % beta cell than adult; P11 also had significantly lower than P1–2 but not P21. Thus the changes in gene expression are likely to be due to changes in phenotype rather than proportion of beta cells. By western blot, MAFA protein (c) and PDX1 (d) protein are low at birth (P2). MAFA increases at P11 but is still low compared with adult. PDX1 increased at P11 and decreased in adult islets in a pattern similar to that of mRNA levels at the same ages. Representative gels of three independent samples. Ad, adult

Table 1.

Time course expression of islet transcription factors

| Transcription factor | Age (days) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 21 | 28 | |

| Mafa | 0.09±0.06* | 0.07±0.03* | 0.43±0.02* | 0.38±0.05* | 0.41±0.02* | 0.42±0.05* | 0.22±0.08* | 0.48±0.07 |

| Pdx1 | 0.12±0.06* | 0.62±0.24 | 2.17±0.36 | 1.97±0.69 | 1.93±0.52 | 0.54±0.14 | 0.24±0.07* | 0.44±0.1 |

| Neurod1 | 0.12±0.09* | 0.58±0.08 | 4.4±0.15* | 3.18±0.29* | 4.22±1.01* | 1.24±0.18 | 0.63±0.16 | 1.38±0.16 |

| Nkx6-1 | 0.03±0.02* | 0.22±0.09* | 0.66±0.02 | 0.59±0.04 | 0.82±0.13 | 0.61±0.18 | 1.09±0.15 | 0.82±0.08 |

| Mafb | 0.62±0.32 | 3.25±0.51* | 15.51±3.95* | 14.24±2.08* | 19.3±1.91* | 4.96±0.94* | 2.78±0.91* | 4.49±0.8* |

Mean ± SEM;

p<0.05

Values are fold change with respect to adult islets

We further explored the role of Pdx1 and Mafa in functional maturation because both are major regulators of insulin gene expression. Mafa expression during the neonatal period seemed independent of Pdx1 expression. Interestingly, the pattern of insulin mRNA mirrored more closely that of Mafa than either Pdx1 or Neurod1 (Fig. 1a, b).

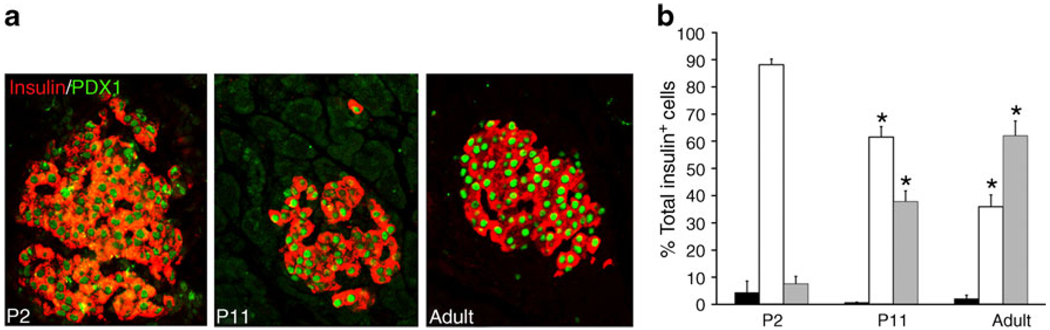

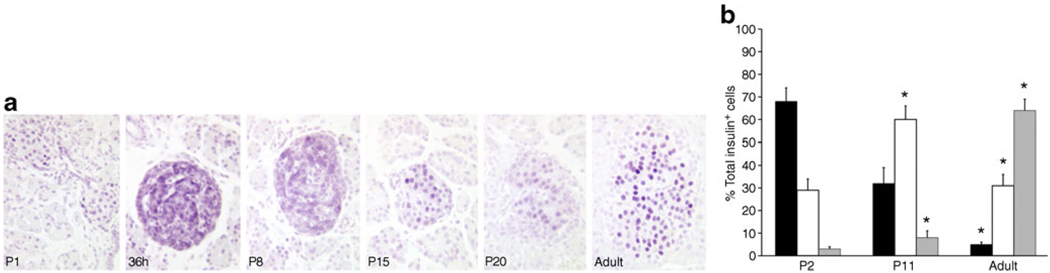

MAFA protein levels showed age-dependent increases. In western blots, MAFA protein (Fig. 1c) reflected the RNA levels with very low levels in P2 islets and increases in P11. PDX1 protein, by western blot (Fig. 1d) and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2a), showed comparable levels at P11 and adult, whereas mRNA levels tended to be higher at P11 (Fig. 1a). The higher mRNA than protein levels may reflect the presence of cytoplasmic PDX1 at P2 and P11 and post-transcriptional regulation of PDX1. At P2 about 90% of beta cells had PDX1low staining (Fig. 2a, b); PDX1high beta cells increased from 10% at P2, to 40% at P11 and 60% in adult islets. Similarly MAFA protein was produced at low levels at P0; by 36 h of age most of the protein in the majority of cells was cytoplasmic and by P15 had become increasingly nuclear (Fig. 3a). It was possible to evaluate subcellular MAFA localisation with insulin counterstaining, which clearly demarcates cytoplasmic vs nuclear compartments. At P2 (Fig. 3b, ESM Fig. 2), 68% of beta cells had no detectable nuclear MAFA and by P11 60% had low levels of nuclear MAFA protein, while in the adult 95% had detectable nuclear MAFA staining (64% MAFAhigh and 31% MAFAlow). At the early ages both nuclear and cytoplasmic MAFA were seen in different islets within the same pancreas (ESM Fig. 3); it was the proportion of cells expressing nuclear MAFA that changed with age. At P1 nuclear MAFA staining was seen in 26% MAFA-positive cells but at P10 in 76%. Murine beta cells also produced cytoplasmic MAFA at P0 and P2 (ESM Fig. 4), but by P7 their nuclear MAFA level was greater than seen in rats at similar age. These data show that by P11, Pdx1 mRNA and nuclear protein levels approached that of adult, whereas Mafa mRNA and nuclear protein remained significantly lower than adults.

Fig. 2.

PDX1 protein levels change in intensity during the postnatal period. a By immunostaining, PDX1 protein (green) in insulin+ cells (red) is low at birth (P2) and increases progressively until most beta cells are PDX1high in adults. b Quantification of nuclear PDX1 levels shows that already at P2 almost all insulin positive cells produced detectable PDX1 and the intensity of staining increases with age. Undetectable PDX1 (black bars), PDX 1low (white bars), PDX 1high (grey bars). Total insulin+ cells counted: P2, 463; P11, 2,286; adult, 1,092 (five pancreases per age). Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 with respect to previous age

Fig. 3.

MAFA protein levels change in intensity and localisation during the postnatal period. a By immunostaining, MAFA protein is low at birth (P0) and mainly cytoplasmic at 36 h after birth. By P15 it has increased and has more nuclear localisation. In adult islets MAFA protein is clearly nuclear. b Quantification of nuclear MAFA levels from immunofluorescent images (see ESM Fig. 2) showed at P2 only 30% MAFAlow insulin positive cells (white bar) and less than 5% MAFAhigh (grey bar) while the rest had undetectable MAFA levels (black bar). In the adult 95% of beta cells were MAFA+ (high+low). Total insulin+ cells counted: P2, 654 cells from four pancreases; P11, 1,140 cells from four pancreases; adult, 2,127 cells from five pancreases. Mean ± SEM; *p<0.05 with respect to previous age

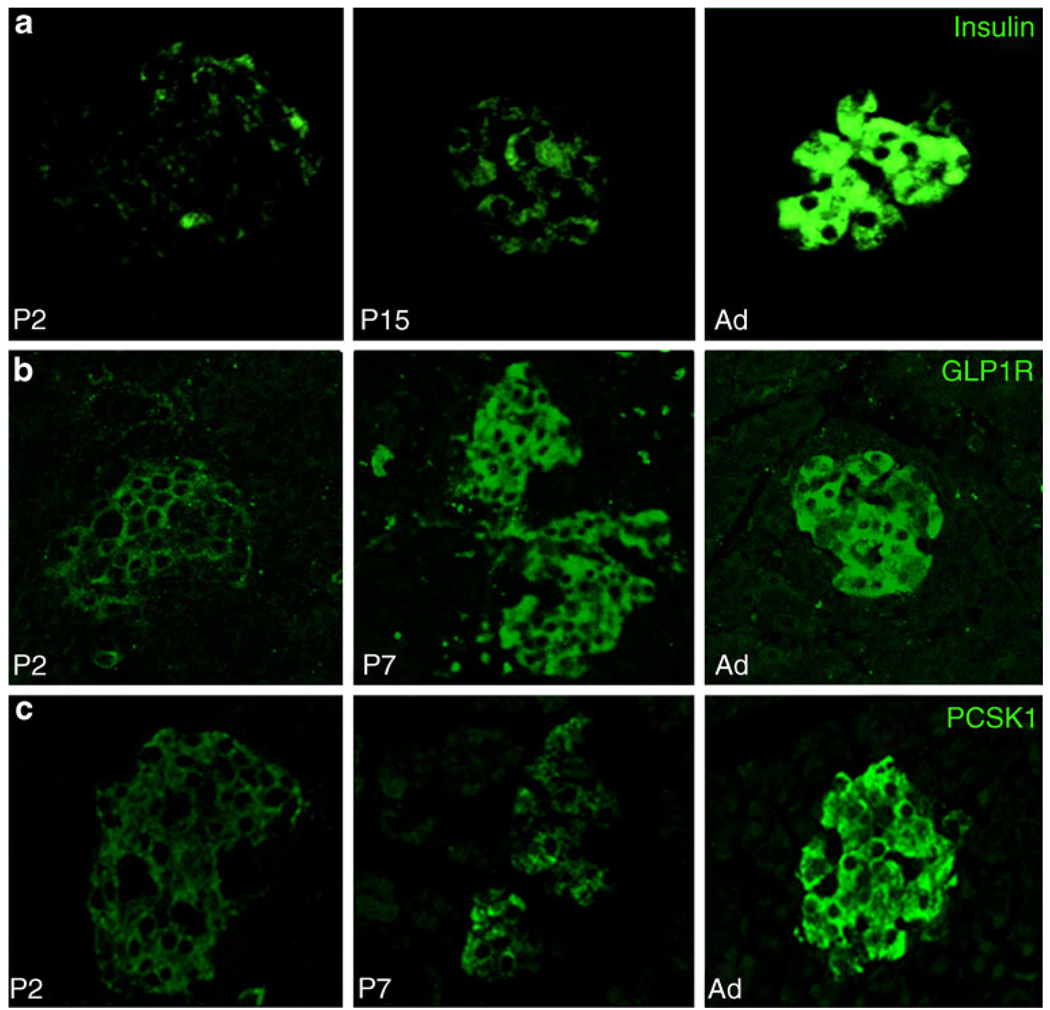

Putative Mafa targets (insulin, Glut2, Gck, Glp1r and Pcsk1) had an expression pattern similar to that of Mafa, with very low expression at P2, and significant increases from P7 to P9; however, unlike Mafa, these genes reached adult mRNA levels by P28 (Fig. 1b). Immunostained neonatal pancreas showed corresponding increases in insulin, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) and PCSK1 proteins with age (Fig. 4). As the tissues and sections were handled identically and all images were taken in parallel at the same settings, signal intensity differences reflect differences in protein production. Interestingly, Gck mRNA increased from 10% adult level at P7 to 168% at P9, which was maintained up to P28. Most other genes were unchanged over the neonatal period, e.g. catalase, a scavenger enzyme that has low levels in adult islets (ESM Fig. 1). The findings that Pdx1 expression reached adult levels already by P7 whereas Mafa expression remained significantly lower than adult even through P21 suggest Mafa as the factor that drives final maturation of beta cell function and enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

Fig. 4.

Proteins of selected genes have similar age-dependent increases as mRNA. Insulin (a), GLP1R (b) and PCSK1 (c) had very low levels of immunostaining at P2, increasing until adult. To allow comparison of protein levels at different ages paraffin sections were immunostained in parallel and photographed in confocal mode at same settings. Ad, adult

Adenoviral overexpression of Pdx1 and MAFA in P2 islets

To determine the effect of Pdx1 and Mafa on the maturation of the neonatal beta cells more directly, we overexpressed each separately using adenoviruses in P2 islets and assessed expression of putative target genes, nuclear localisation of the transcription factor and glucose-responsive insulin secretion.

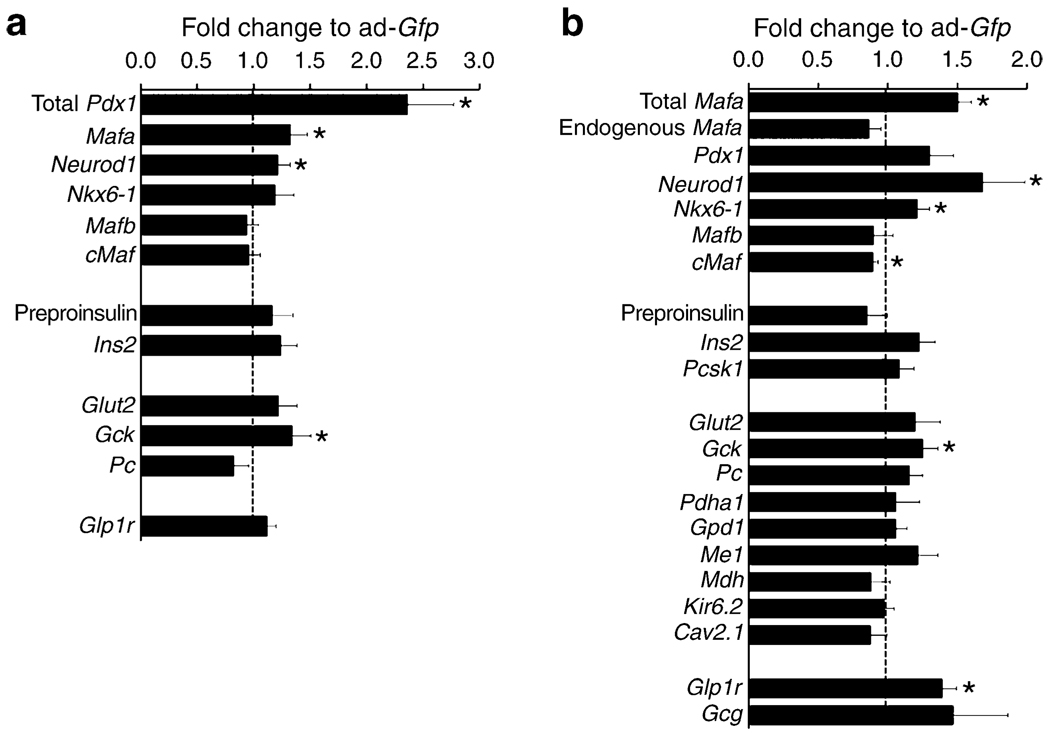

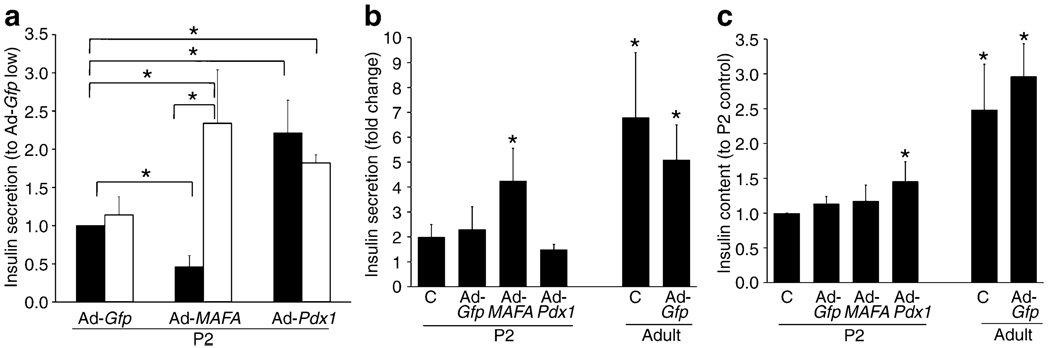

Pdx1 overexpression achieved a 2.4-fold increase in mRNA (Fig. 5a), with significant increases in Mafa, Neurod1 and Gck mRNA, but no change in Nkx6-1, cMaf (also known as Maf), Mafb, Glp1r, Glut2 (also known as Slc2a2), Ins2, preproinsulin or pyruvate carboxylase mRNA. Insulin secretion was significantly increased at both 2.8 and 16.8 mmol/l glucose (Fig. 6a) in Ad-Pdx1-infected cells compared with Ad-Gfp controls. However, there was no increase in fold change because the responses to low and high glucose did not differ (Fig. 6b). This lack of glucose responsiveness was seen even though insulin content significantly increased after Pdx1 overexpression (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 5.

Effect of adenoviral-mediated increase of Pdx1 and Mafa on genes important for beta cell function. After 72 h culture adenoviral-mediated overexpression of Pdx1 (a) or MAFA (b) P2 islets had significant increases of total Mafa mRNA (hMAFA; see Methods) and total Pdx1 mRNA. Overexpression of Pdx1 upregulated Mafa, Neurod1 and Gck whereas overexpression of Mafa had upregulated Neurod1, Nkx6-1, Gck and Glp1r. Quantitative RT-PCR; expression compared with Ad-Gfp infected cells (equal to 1, dotted line). Mean ± SEM, n=4–6 independent experiments; *p<0.05

Fig. 6.

Insulin secretion in static incubation and insulin content after Ad-Pdx1, Ad-MAFA and Ad-Gfp infection. a Insulin secretion in response to 16.8 mmol/l (white bar) glucose increased in both Ad-Pdx1 and Ad-MAFA infected P2 cells compared with Ad-Gfp infected cells after 5 days culture. However, insulin secretion in 2.6 mmol/l (black bar) glucose from Ad-MAFA infected cells significantly decreased while that from Ad-Pdx1 increased almost as much as with high glucose.*p<0.05 in marked comparisons. b Insulin secretion expressed as fold change in response to glucose stimulation reflects the glucose responsiveness of the cultured cells. As previously shown, neonatal (P2) islets have little glucose responsiveness when compared with adult islets similarly cultured (Ad-GfpP2: 7±2 pg insulin/ng DNA at 2.8 mmol/l and 9±2 at 16.8 mmol/l; Ad-Gfp adult: 11±2 pg insulin/ng DNA at 2.8 mmol/l and 47±13 at 16.8 mmol/l). Only Ad-MAFA increased the glucose responsiveness of the P2 cells; the uninfected, Ad-Gfp and Ad-Pdx1 infected cells had little to no response to the increased glucose concentration. *p<0.05 compared with untreated cultured P2 cells (c). c There was no change in insulin content (pg/ng DNA) in Ad-MAFA infected P2 islets and cultured control islets (untreated or Ad-Gfp infected), but insulin content was significantly higher in Ad-Pdx1 compared with cultured uninfected (c) cells. Mean ± SEM; n=4 independent experiments in duplicate. *p<0.05 compared with untreated (c) cultured P2 cells

MAFA overexpression was adjusted to obtain a modest 50% increase of Mafa levels at 72 h compared with control Ad-Gfp-infected cells; this is comparable to the level seen in P9–P28 islets. This change was due to increased exogenous MAFA as the amount of PCR product for 3′ UTR message (endogenous gene, see Methods) was unchanged (Fig. 5b). With this overexpression, transcription of Neurod1, Nkx6-1 and Gck were significantly upregulated, as was Glp1r. However, Ins2, Pdx1, Glut2, various metabolic genes and channels were not significantly changed. There was no change in Mafb, whereas c-Maf was significantly reduced.

In addition to the enhanced expression of several key genes, MAFA overexpression in P2 cells increased nuclear levels of MAFA. As with the islets within the pancreas (Fig. 3), Ad-Gfp islet cells after 72 h infection had low nuclear MAFA protein: 51% of these cells had no detectable nuclear MAFA. However, Ad-MAFA cells were 91% MAFA-positive with 38% MAFAhigh and 53% MAFAlow nuclear staining (ESM Fig. 5a). As the human MAFA vector included an Herpes simplex virus (HSV) tag, we confirmed that the adenoviral-expressed human MAFA in infected cells was preferentially localised in the nucleus (ESM Fig. 5b).

Importantly, MAFA overexpression induced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. In static incubations Ad-MAFA-infected cells significantly decreased basal insulin secretion at 2.8 mmol/l glucose while significantly increasing insulin secretion in 16.8 mmol/l glucose compared with Ad-Gfp cells (Fig. 6a). Insulin secretion increased fourfold from low to high glucose (Fig. 6b), a change comparable to the fivefold increase of cultured Ad-Gfp-infected adult cells. It is striking that adult glucose responsiveness was nearly achieved in MAFA-infected P2 cells that still had lower insulin expression (Figs 1b, 5b) and content (Fig. 6c) than adult cells treated and cultured under the same conditions. Considering that only about 50% of the cells were infected, the glucose responsiveness may be underestimated in these experiments. It is important to note that these Ad-infected P2 isolated islets were cultured for 5 days and thus cannot be compared with freshly isolated P2 islets.

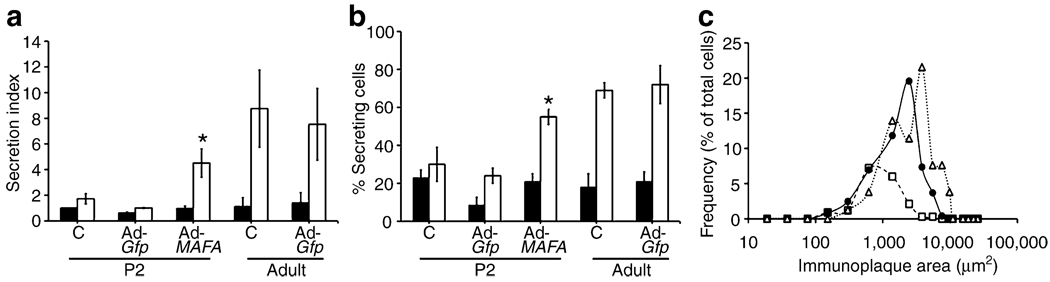

Using the more informative RHPA to explore in more detail the improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in MAFA-overexpressing cells, we found both increased proportion of glucose-responsive cells and greater amount of insulin secreted in response to high glucose. As previously shown [26], RHPA allows the evaluation of secretion from single beta cells by detection of haemolytic plaques, whose area is proportional to the amount of insulin secreted by that individual cell (ESM Fig. 6). Confirming the previously reported lack of glucose responsiveness in neonatal rodent islets [3–5], uninfected and Ad-Gfp-infected cultured P2 controls had little response to stimulatory glucose concentrations (Fig. 7a). By contrast, robust insulin secretion was observed in uninfected and Ad-Gfp-infected cultured adult cells, which had 7.8- and 5.4-fold greater insulin secretion index at 16.8 mmol/l glucose than at 2.8 mmol/l. The secretion index of Ad-MAFA P2 cells was 4.7-fold greater at 16.8 mmol/l glucose than at 2.8 mmol/l (Fig. 7a), approaching that of adult cells.

Fig. 7.

Mafa expression increases percentage of secreting cells and insulin secreted per beta cell as measured by reverse haemolytic plaque assay. a After Ad-MAFA infection, cultured P2 cells have increased insulin secretion index in response to glucose stimulation; 2.6 mmol/l (black bar), 16.8 mmol/l (white bar). Mean ± SEM; n=3 independent experiments. *p<0.03 respect to Ad-Gfp P2. Total number of plaques counted per condition: P2 untreated (c), 223; Ad-Gfp P2, 595; Ad-MAFA P2, 463; untreated (c) cultured adult, 188; cultured adult Ad-Gfp, 256. b The percentage of insulin-secreting beta cells increased after Ad-MAFA infection. *p<0.005 respect to Ad-Gfp P2; 2.6 mmol/l (black bar), 16.8 mmol/l (white bar). c In response to stimulatory 16.8 mmol/l glucose, more Ad-MAFA cells are secreting and with greater individual secretion, as seen in this plot of the subpopulations from a representative experiment. P2 Adv-Gfp (white square), P2 Adv-MAFA (black circle), adult control (white triangle)

The effects of Ad-MAFA on insulin secretion by neonatal islets were due partly to inducing responsiveness as seen by the significantly increased percentage of secreting cells at 16.8 mmol/l glucose (Fig. 7b): 30% for uninfected, 24% for Ad-Gfp-infected cells but 55% for Ad-MAFA infected. This proportion of responding cells approached that of adults (69% for uninfected and 72% for Ad-Gfp). In addition, the overexpression of MAFA changed the functional subpopulations of beta cells (Fig. 7c). Adult beta cells can be grouped on their secretory capacity into three functional subpopulations by plaque areas: small, medium and large plaque-forming cells (ESM Fig. 6). In control Ad-Gfp cultured cells, the majority of cells were small plaque-forming with few of the other subpopulations. However, in Ad-MAFA beta cells the proportion of small plaque-forming cells decreased as the other two populations increased, rendering the secretory characteristics of these infected cells similar to that of adult both in number and size of secretion plaques. Thus, increased expression of Mafa in glucose-unresponsive cultured islet cells induced a functional change in these cells such that they had near-adult glucose-induced insulin secretion, a sign of maturation.

Discussion

Beta cells at birth are functionally immature, lacking the ability to respond to a changing glucose concentration, only acquiring glucose responsiveness over the first 3–4 weeks after birth [5, 25]. Here, we tested two of the three suggested transcription factors essential for beta cell specificity and insulin gene expression. We demonstrated a close relationship between the expression patterns of Mafa and some of its putative targets, including insulin, during this neonatal period. As Mafa expression from P2 through P7 was less than 10% of adult, reconstitution of Mafa at P2 provides a means to unequivocally evaluate effects of Mafa on beta cell functional development.

In such reconstitution experiments, overexpressing MAFA in neonatal cells led to their acquisition of an insulin-secretory profile similar to adult beta cells, with a higher percentage of secreting cells as well as greater insulin secretion in response to high glucose concentrations. Thus, increased Mafa expression may represent a mechanism responsible for enhancing the beta cell functional maturity. By contrast, Pdx1 reached adult levels by P7 and had a postnatal expression pattern that differed from the tested beta cell genes including insulin, Glut2 and Gck. Importantly, Pdx1 reconstitution in P2 beta cells failed to increase glucose responsiveness within the experimental timeframe. However, Pdx1 overexpression upregulated Mafa mRNA expression, increased insulin content and increased insulin secretion in both low and high glucose concentrations.

The expression patterns of Mafa and Pdx1 during the neonatal period were distinct even though both have been implicated in regulating expression of the other [13, 27, 28]. The parallel expression of insulin and Mafa, the upregulation of Mafa expression by Ad-Pdx1, and our previous observation that PDX1high is expressed before MAFA in insulin+ cells during development [11] are consistent with Pdx1 being an upstream regulator of Mafa. Even though the induction of glucose responsiveness was not achieved by Pdx1 overexpression within the timeframe of our experiments, we expect that with longer incubation Pdx1-infected P2 cells would acquire glucose responsiveness.

Mafb is also implicated in regulating Mafa expression [29], yet our results suggest the lack of such regulation in postnatal beta cells. Mafb expression had a similar pattern to Pdx1 and Neurod1 between P7 and P15, a period when the proportion of glucagon-expressing alpha cells does not increase [30]. Two likely contributors to enhanced Mafb expression are induction of Mafb in maturing glucagon+ cells and transient production of MAFB [11] in beta cells formed after birth [31, 32]. In the mouse around P14 only a few insulin+ cells are still MAFB+ [11, 33]. The dramatic reduction in expression of Pdx1, Neurod1 and Mafb about P15 was not accompanied by reduced Mafa expression and so suggests additional factors may regulate Mafa expression during this time.

A previous report [13] had suggested Gck, Pcsk1 and Glp1r as putative Mafa targets. As Mafa knockout mice did not show any embryonic phenotype, it was not surprising that a recently published paper [33] failed to detect these genes as being directly under the control of either Mafa or Mafb in E18.5 Mafbnull or MafaDPancMafbnull mice. However, our data of parallel expression of Glp1r, insulin, Glut2 and Pcsk1 with Mafa support their being Mafa targets postnatally. Gck expression was upregulated by both Pdx1 and Mafa overexpression, yet the time course of its expression differed significantly from both. In addition to Mafa and Pdx1, physiological stimuli, such as thyroid hormones [34], may regulate Gck expression.

In our previous report showing developing insulin+ cells switching from MAFB+MAFA−INS+ to MAFB−MAFA+INS+ cells [11], we suggested that Mafa may be important for the postnatal functional maturation of beta cells. Our current results strongly indicate such a role. While global Mafa-knockout mice showed embryonic Mafa expression was not essential for islet architecture at birth, that study did not address its function in maturation of beta cells [19]. A modest increase in fasting glucose at 4 weeks was the earliest defect reported in the Mafa knockout mice, and this was followed by impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion at 8 weeks. There was no analysis of whether this impairment was due to a lack of maturation, an intrinsic defect or glucotoxicity. Neonatal rodent beta cells are analogous to a loss-of-function model owing to their very low Mafa expression at birth, and we suggest that the acquisition with mature beta cell function after reconstitution of Mafa expression to levels comparable with adult beta cells essentially represents a functional rescue. Demonstration of physiological signals regulating Mafa expression during the neonatal period will underscore its importance as an essential transcription factor for functional maturation of beta cells.

In the early neonatal period in rodents (Fig. 3, ESM Fig. 2) MAFA protein not only has a very low expression but has mainly cytoplasmic localisation; with time it gains nuclear localisation. The relative proportion of nuclear and cytoplasmic MAFA differs somewhat between rats and mice during this period, but the presence of some cytoplasmic MAFA across species suggests that such translocation is a normal feature of neonatal development. Although the mechanisms controlling MAFA localisation in beta cells during the postnatal period are unknown and beyond the scope of this work, cytoplasmic localisation of transcription factors has been described [35, 36]. Recently a nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of MAFA was described as a result of oxidative stress in the adult beta cell [37].

Maternal hyperglycaemia leads to precocious maturation and hyperplasia of fetal beta cells [4, 38], and chronic in vitro exposure of fetal beta cells to elevated glucose levels induced maturation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [4]. Both Mafa and Pdx1 are glucose-responsive transcription factors and so could have enhanced expression. However, increased expression of Mafa, but not Pdx1, converted immature neonatal beta cells into glucose-responsive cells within the timeframe studied, supporting the more direct role of Mafa in the maturation process.

Although much emphasis has been put on elucidating the transcription factors involved in the embryonic differentiation of beta cells (reviewed by Jensen [39]), identification of factors that drive functional maturation in the postnatal period is essential to harvest the true potential of human embryonic stem (hES) cells. Currently, differentiated insulin-positive cells derived in vitro lack glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and still express MAFB [1, 20]. Only several months after transplantation, these hES cell-derived insulin+ cells were shown to be glucose responsive and to express MAFA [2]. Conversely, the loss of Mafa mRNA and protein expression occur in dysfunctional beta cells from rats 4 weeks after 90% pancreatectomy and from 12-week-old hyperglycaemic db/db mice [40]. Thus, identification of the neonatal physiological stimuli that regulate Mafa and Pdx1 expression will be important for developing in vitro strategies to convert stem-cell derived insulin-expressing cells into mature, fully functional beta cells for cell-based therapies for diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Lock, T. Salameh and C. Cahill, all of the Joslin Diabetes Center, for their expert technical assistance. This study was supported by NIH R01 DK 66056 (S. Bonner-Weir), R01 DK 60127 (A. Sharma), P30 DK36836 Joslin Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (DERC) Advanced Microscopy Core grants as well as the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, Diabetes Research and Wellness Foundation, the Graetz Fund and an important group of private donors. I. El Khattabi was supported by Joslin T32 DK007260, W. C. Li by a JDRF Post doctoral fellowship, A. Koh by a Singapore National Medical Research Council Research fellowship grant, and K. Juhl by a Lundbeckfonden fellowship.

Abbreviations

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- GLP1R

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor

- GCK

Glucokinase

- GLP1R

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor

- MAFA

v-Maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homologue A (avian)

- MAFB

v-Maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homologue B (avian)

- PCSK1

Prohormone convertase 1/3

- PDX1

Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1

- RHPA

Reverse haemolytic plaque assay

- TBST

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20

- UTR

Untranslated

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-010-2026-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Duality of interest The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contributor Information

A. Sharma, Email: arun.sharma@joslin.harvard.edu.

S. Bonner-Weir, Email: susan.bonner-weir@joslin.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.D’Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:443–452. doi: 10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freinkel N, Lewis NJ, Johnson R, Swenne I, Bone A, Hellerstrom C. Differential effects of age vs glycemic stimulation on the maturation of insulin stimulus-secretion coupling during culture of fetal rat islets. Diabetes. 1984;33:1028–1038. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.11.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellerstrom C, Swenne I. Functional maturation and proliferation of fetal pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 1991;40 Suppl 2:89–93. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bliss CR, Sharp GW. Glucose-induced insulin release in islets of young rats: time-dependent potentiation and effects of 2-bromostearate. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:E890–E896. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.5.E890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarro-Tableros V, Fiordelisio T, Hernandez-Cruz A, Hiriart M. Physiological development of insulin secretion, calcium channels, and GLUT2 expression of pancreatic rat beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1018–E1029. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00457.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rorsman P, Arkhammar P, Bokvist K, et al. Failure of glucose to elicit a normal secretory response in fetal pancreatic beta cells results from glucose insensitivity of the ATP-regulated K+channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4505–4509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bliss CR, Sharp GW. A critical period in the development of the insulin secretory response to glucose in fetal rat pancreas. Life Sci. 1994;55:423–427. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan C, Tuch BE, Tu J, Brown SA. Role of NADH shuttles in glucose-induced insulin secretion from fetal beta-cells. Diabetes. 2002;51:2989–2996. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jermendy A, Toschi E, Aye T, et al. Rat neonatal beta cells lack the specialised metabolic phenotype of mature beta cells. Diabetologia. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-2036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura W, Kondo T, Salameh T, et al. A switch from MafB to MafA expression accompanies differentiation to pancreatic beta-cells. Dev Biol. 2006;293:526–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller DM, McWeeney S, Arsenlis A, et al. Characterization of pancreatic transcription factor Pdx-1 binding sites using promoter microarray and serial analysis of chromatin occupancy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32084–32092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Brun T, Kataoka K, Sharma AJ, Wollheim CB. MAFA controls genes implicated in insulin biosynthesis and secretion. Diabetologia. 2007;50:348–358. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0490-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, et al. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, Edlund H. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature. 1994;371:606–609. doi: 10.1038/371606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Stein R. Glucose-induced transcription of the insulin gene is mediated by factors required for beta-cell-type-specific expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:871–879. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waeber G, Thompson N, Nicod P, Bonny C. Transcriptional activation of the GLUT2 gene by the IPF-1/STF-1/IDX-1 homeobox factor. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1327–1334. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.11.8923459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, Simu K, Edlund H. beta-cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the beta-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1763–1768. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Moriguchi T, Kajihara M, et al. MafA is a key regulator of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4969–4976. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4969-4976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang J, Au M, Lu K, et al. Generation of insulin-producing islet-like clusters from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1940–1953. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotoh M, Maki T, Satomi S, et al. Reproducible high yield of rat islets by stationary in vitro digestion following pancreatic ductal or portal venous collagenase injection. Transplantation. 1987;43:725–730. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198705000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature. 2008;455:627–632. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heller RS, Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. Insulinotropic glucagon-like peptide I receptor expression in glucagon-producing alpha-cells of the rat endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 1997;46:785–791. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuppin GT, Bonner-Weir S, Montana E, Kaiser N, Weir GC. Replication of adult pancreatic-beta cells cultured on bovine corneal endothelial cell extracellular matrix. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1993;29A:339–344. doi: 10.1007/BF02633963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguayo-Mazzucato C, Sanchez-Soto C, Godinez-Puig V, Gutierrez-Ospina G, Hiriart M. Restructuring of pancreatic islets and insulin secretion in a postnatal critical window. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salomon D, Meda P. Heterogeneity and contact-dependent regulation of hormone secretion by individual B cells. Exp Cell Res. 1986;162:507–520. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samaras SE, Zhao L, Means A, Henderson E, Matsuoka TA, Stein R. The islet beta cell-enriched RIPE3b1/Maf transcription factor regulates pdx-1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12263–12270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raum JC, Gerrish K, Artner I, et al. FoxA2, Nkx2.2, and PDX-1 regulate islet beta-cell-specific mafA expression through conserved sequences located between base pairs −8118 and −7750 upstream from the transcription start site. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5735–5743. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00249-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artner I, Blanchi B, Raum JC, et al. MafB is required for islet beta cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3853–3858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700013104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scaglia L, Cahill CJ, Finegood DT, Bonner-Weir S. Apoptosis participates in the remodeling of the endocrine pancreas in the neonatal rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1736–1741. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonner-Weir S, Toschi E, Inada A, et al. The pancreatic ductal epithelium serves as a potential pool of progenitor cells. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5 Suppl 2:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chintinne M, Stange G, Denys B, et al. Contribution of postnatally formed small beta cell aggregates to functional beta cell mass in adult rat pancreas. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2380–2388. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1851-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Artner I, Hang Y, Mazur M, et al. MafA and MafB regulate genes critical to β cells in a unique temporal manner. Diabetes. 2010;59:2530–2539. doi: 10.2337/db10-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Partridge NC, Hoh CH, Weaver PK, Oliver IT. Premature induction of glucokinase in the neonatal rat by thyroid hormone. Eur J Biochem. 1975;51:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb03905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumoto M, Accili D. All roads lead to FoxO. Cell Metab. 2005;1:215–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kishi A, Nakamura T, Nishio Y, Maegawa H, Kashiwagi A. Sumoylation of Pdx1 is associated with its nuclear localization and insulin gene activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E830–E840. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00390.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harmon JS, Bogdani M, Parazzoli SD, et al. Beta-cell-specific overexpression of glutathione peroxidase preserves intra-nuclear MafA and reverses diabetes in db/db mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4855–4862. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aerts L, van Assche FA. Rat foetal endocrine pancreas in experimental diabetes. J Endocrinol. 1977;73:339–346. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0730339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen J. Gene regulatory factors in pancreatic development. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:176–200. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondo T, El Khattabi I, Nishimura W, et al. p38 MAPK is a major regulator of MafA protein stability under oxidative stress. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1281–1290. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.