Abstract

We present a rare case of endocarditis in a 33-year-old woman with a splenectomy. The patient presented with meningeal symptoms and was diagnosed with endocarditis on the medical admissions unit using a portable echocardiography machine. Bordetella holmesii was cultured from the blood on admission and the patient underwent subsequent aortic valve replacement. We discuss the importance of echo skills within the specialty of acute medicine and the benefits of swift senior review at the front door. We emphasise the guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis for the post-splenectomy patient as well as discuss the pathogen B holmesii and its growing association of septicaemia in asplenic individuals.

Background

This case demonstrates the importance of the growing specialty of acute medicine. Acutely unwell patients who are seen swiftly by experienced individuals with appropriate skills such as echocardiography will improve patient outcomes and the patient journey.

There have been only two previously documented case reports of Bordetella holmesii endocarditis and both were in asplenic patients similar to our case report.

This case highlights that asplenic patients are not following the current guidelines regarding antibiotic treatment and vaccinations, and have little insight into opportunistic post-splenectomy infections (OPSIs).

Case presentation

A 34-year-old female caterer of Chinese origin presented to her general practitioner (GP) with a fever of 40°C in a drowsy and incoherent state. The GP administered an intramuscular injection of benzylpenicillin, suspecting meningitis. The patient was referred to the medical admissions unit (MAU) where she was seen immediately by the senior house officer. She gave a 3 month history of feeling unwell with intermittent fevers, myalgia, headaches and neck stiffness. Her headaches were occipital in nature and usually worse in the morning. She reported no rash and no photophobia. There was no history of loss of appetite or weight loss.

The patient had undergone a splenectomy 9 years earlier following a prolonged course of steroids for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She took prophylactic penicillin after her splenectomy but stopped after 3 years following advice from her GP. There was no other significant past medical history. There was no history of recent travel. She was not taking any regular medications and admitted to having a yearly flu injection.

On examination the patient was sweaty with a temperature of 38.5°C, a pulse of 94 beats/min, and blood pressure of 115/60 mm Hg. She described pain on flexing her neck but Kernigs was negative. There was no rash or photophobia. Fundoscopy and full neurological examination were normal. There were no peripheral stigmata of subacute bacterial endocarditis but she was found to have a diastolic murmur. Her chest was clear and abdomen was soft, with the presence of a splenectomy scar. Her urine dip stick was negative for blood and protein.

Investigations

Her initial blood results revealed a total white blood cell count (WBC) of 12.7×109/l (neutrophilia) and a C reactive protein (CRP) concentration of 128 mg/l. Liver function tests were abnormal with a bilirubin value of 21 μmol/l, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 100 iu/l, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 758 iu/l, albumin 41 g/l, and an international normalised ratio (INR) of 1.2. Admission glucose was normal. The patient was reviewed within an hour of admission by the consultant on call and it was decided an urgent echocardiogram should be undertaken in view of auscultatory findings of a diastolic murmur. The consultant elicited a negative Kernig’s and the decision made was that this was not meningism. A bedside echocardiogram revealed a thickened aortic valve with suspicion of a vegetation on the left coronary cusp of the aortic valve with severe aortic regurgitation. A diagnosis of subacute bacterial endocarditis was made (figs 1–3). The patient received immediate intravenous vancomycin (1 g) and gentamicin (300 mg). Despite antibiotic treatment the patient continued to spike temperatures and a trans-oesophageal echocardiogram was undertaken. This ruled out an aortic root abscess but confirmed the presence of a vegetation on the left coronary cusp of the aortic valve and severe aortic regurgitation.

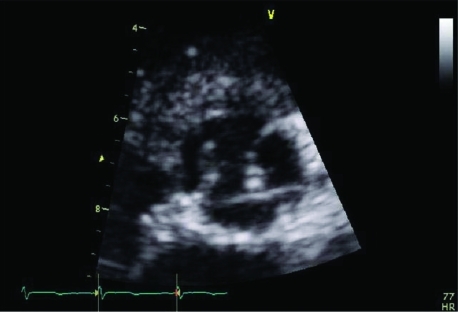

Figure 1.

An area of increased density is seen on the left coronary cusp, suggestive of a vegetation.

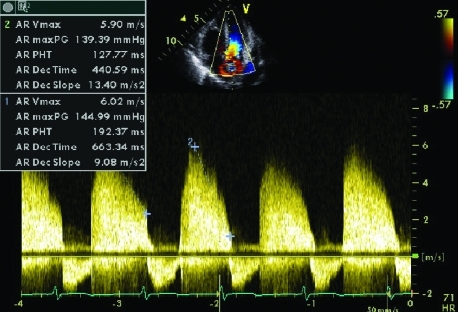

Figure 3.

Continuous wave Doppler signal showing severe aortic regurgitation. Severe aortic regurgitation is characterised by a pressure half time of <250 ms, and a dense Doppler signal with high velocities (6 m/s).

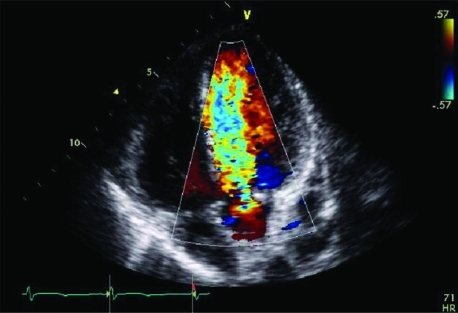

Figure 2.

Apical five chamber view showing severe aortic regurgitation. Colour flow studies show a broad regurgitant jet (blue) entering the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) and extending up to the left ventricular apex, indicative of severe aortic regurgitation.

Outcome and follow-up

Initial reports from microbiological studies indicated an organism from the HACEK (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella) group. Four weeks later, Bordetella holmesii was isolated.

The patient’s antibiotic treatment (cefotaxime 2 g intravenously three times a day) continued for a further 4 weeks before she underwent mechanical aortic valve replacement (fig 4). She made an uneventful recovery.

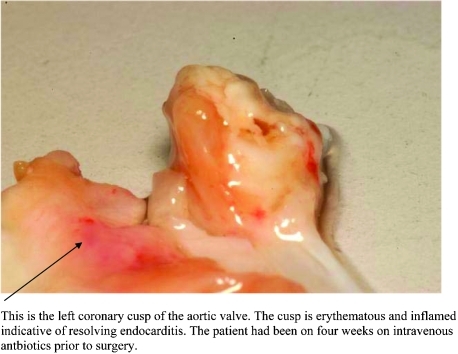

Figure 4.

Macroscopic image of the aortic valve post-resection. This is the left coronary cusp of the aortic valve. The cusp is erythematous and inflamed, indicative of resolving endocarditis. The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics for 4 weeks before surgery.

Discussion

Echo at the front door

This case demonstrates how echocardiography at the bedside can support a diagnosis suspected from good clinical examination. By making a swift diagnosis on the MAU the patient’s journey can be improved along with reductions in National Health Service costs and in patient length of stay. It can also decrease pressures on departmental echo services, which can be overwhelmed with inappropriate referrals.

Echocardiography has traditionally been used in the hands of cardiologists and cardiac physiologists. However, with the era of portable echo machines, the use of echocardiography has extended into various forums including the MAU, accident and emergency department, intensive therapy unit, and the community.1 For acute physicians there are clear benefits to having echocardiography as a skill to assist with the prompt diagnosis of conditions, such as suspected cardiac tamponade, massive pulmonary embolism, new murmur post-myocardial infarction, suspected aortic aneurysm, suspected pericardial effusion and persistent low blood pressure. Rapid answers to important and life changing clinical questions will ultimately improve diagnostic speed and accuracy, management and patient outcome.

An interesting clinical feature of this case is that this patient presented with meningeal symptoms: headache, fever, and neck stiffness. These symptoms are recognised in endocarditis and are due to a cytokine medicated systemic inflammatory response. The initial diagnosis made by the GP as well as the senior house officer was that of meningitis. However, swift senior review revealed no meningeal signs, but a diastolic murmur which previously had not been appreciated. There were no signs in keeping with neurological sequelae of endocarditis such as septic emboli. This led to the diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis being made and urgent bedside echocardiography. Access to an echo machine and an on-call medical registrar trained in echocardiography were vital in the management of this case. Our case therefore highlights the importance of prompt senior (consultant) review as well as good decision making on the MAU.2 It also highlights the value of echocardiography skills and equipment in the acute setting.3–5

Prophylaxis guidelines post-splenectomy

The spleen is part of our immunological defence system and without it individuals are at risk of infection, especially that of encapsulated bacteria such as Haemophilus, Streptococcus and Neisseria species.

The British Committee for the Standards in Haematology produced an update in 2002 for their guidelines originally published in 1996 for post-splenectomy patients.6 The key points are:

Life long prophylactic antibiotics are still recommended (oral phenoxypenicillin or erythromycin). Antibiotic prophylaxis is particularly important in the first 2 years post-splenectomy, in children <16 years of age, and those who are immunocompromised.

Patients developing infection despite these measures must be given systemic antibiotics and be admitted urgently to hospital.

All splenectomised patients and those with functional hyposplenism should receive pneumococcal immunisation and Haemophillus influenza type B vaccine. Meningoccocal group C vaccine should also be given in addition to an annual influenza vaccine.

All patients should be educated about the risk of overwhelming infection. Opportunistic post-splenectomy infections (OPSIs), although uncommon, are associated with a high mortality. Lifelong antibiotic prophylaxis is especially important as Pneumovax only offers protection against 75% of infecting strains and OPSI episodes, as vaccine failures have been described in the literature.7 Death rates from OPSI have been reported up to 600 times greater than in the general population, with an estimated lifetime risk of 5%.8 Individuals should be given written information as well as carry an alert card/bracelet or pendent. Our patient had had antibiotic prophylaxis stopped after 3 years and was unaware of both the long term dangers of her previous splenectomy and most of the precautions detailed above. This case supports the view that national guidelines are, unfortunately, not being followed.9

Bordetella holmesii

Bordetella species are small, obligatory aerobic, gram negative coccobacilli, traditionally regarded as respiratory tract parasites. The most recognised is B pertussis, the causative agent for whooping cough. B parapertussis, B bronchiseptica and B avium traditionally are respiratory pathogens on animal hosts. Other species include B hinzii and B trematum.

B holmseii was first isolated in 1983 and the initial article naming the new bacterial species was published in 1995 in honour of Barry Holmes for his substantial contributions to characterisation, classification and identification of unusual pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria.10

B holmesii can cause endocarditis, pneumonia, cellulitus, suppurative arthritis and pyelonephritis.11,12 A clear syndrome of B holmesii bacteraemia has not yet emerged. Since 1995, there have only been a small number of case reports describing the potential clinical manifestations of B holmesii infection. The information available from these cases reports and case studies have been limited due to small numbers of subjects included. There have been only two case reports of B holmesii endocarditis in the literature.11,12 In one report from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) covering the period between 1983 and 2000, which included 26 patients with B holmesii bacteraemia, 22 patients (85%) were asplenic and only two of these presented with endocarditis.11 Further clinical details were not provided. The most prominent and persistent symptom that patients displayed was that of fever.

The time taken to isolate B holmesii can be up to 4 weeks, as in our case, and is due to the lack of oxidase activity and carbohydrate utilisation during culture. This makes it difficult to distinguish it from other phenotypically similar bacteria, such as the Acinetobacter species13 and the CDC non-oxidiser group.14 Once diagnosed, however, intravenous third generation cephalosporins are recommended, particularly for patients with invasive infections.15

Learning points

Swift senior review is key for all acutely sick patients.

Bedside echocardiography is a fundamental skill for acute physicians.

Asplenic patients require education on life long prophylaxis, vaccinations as well as opportunistic post-splenectomy infections (OPSIs).

Bordetella holmesii is a rare pathogen which has a growing association with asplenic patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Senior R, Chambers J. Portable echocardiography: a review. Echocardiography 2006; 13: 3 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College Of Physicians Acute medical care, the right person, in the right setting, first time. Report Of The Acute Medical Task Force. London: RCP, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashrafian H, Bogle RG, Henien M, et al. Portable echocardiography. BMJ 2004; 328: 300–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedson S, Neithardt G, Thomas P, et al. Unsuspected clinically important findings detected with a small portable ultrasound device in patients admitted to a general medical service. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003; 16: 901–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salustri A, Trambaiolo P. Point-of-care echocardiography: small, smart and quick. Eur Heart J 2002; 23: 1484–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The British Committee for The Standards in Haematology Update of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen. 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagham DJ. Overwhelming infection in asplenic patients. Current best practice, preventative measures are not being followed. J Clin Pathol 2001; 54: 214–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch AM, Kapila R. Overwhelming post splenectomy infection. Infec Dis Clin North Am 1996; 10: 693–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramachandra J, Bond A, Ranaboldo C, et al. An Audit of post splenectomy prophylaxis- are we following the guidelines? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003; 85: 252–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weyany RS, Hollis DG, Weaver, et al. Bordetella holmesii sp nov, a new gram negative species associated with septicaemia. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33: 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepard CW, Daneshvar MI, Kaiser RM, et al. Bordetella Holmesii bactaraemia:A newly recognised clinical entity among asplenic patients. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 799–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang YW, Hopkins MK, Kolbert CP, et al. Bordetella holmesii like organism associated with septicaemia, endocarditis, and respiratory failure. Clin infect Dis 1998; 26: 389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber-Smidt P, Tjernberg I, Ursing J. Reliability of phenotypic tests for identification of Acinetobacter species. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29: 277–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollis DG, Moss CW, Daneshaver MI, et al. Characterization of Centers for Disease Control group NO-1, a fastiditious, non oxidative, gram negative organism associated with dog and cat bites. J Clin Micobiol 1993; 31: 746–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindquist SW, Webber DJ, Mangum ME, et al. Bordetella holmesii in an asplenic adolescent. Ped Infect Dis J 1995; 14: 813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]