Abstract

In November 2009, countries around the world reported confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1, including over 6000 deaths. No peak in activity has been seen. The most common causes of death are pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. We report a case of a 55-year-old woman who presented with organising pneumonia associated with influenza A (H1N1) infection confirmed by transbronchial lung biopsy. Organising pneumonia should also be considered as a possible complication of influenza A (H1N1) infection, given that these patients can benefit from early diagnosis and appropriate specific management.

Background

In November 2009, countries around the world reported confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1, including over 6000 deaths.1 No peak in activity has been seen. The most common causes of death are pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome.2 To our knowledge, no histological confirmation of organising pneumonia secondary to H1N1 infection has been reported. Oseltamivir is indicated in patients admitted to hospital with confirmation of influenza A or in patients included in risk groups. In our case, oseltamivir could not prevent the subacute development of organising pneumonia. The organising pneumonia should also be considered as a possible complication of influenza A (H1N1) infection, given that these patients can benefit from early diagnosis and appropriate specific management.

Case presentation

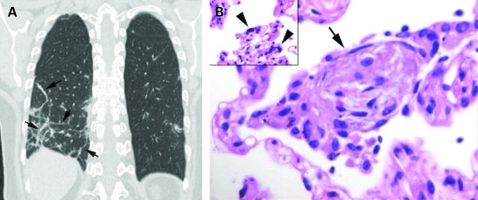

In August 2009, a 55-year-old woman with a history of intermittent asthma attended our emergency department for diffuse myalgia, cough and fever. The symptoms had started 36 h earlier. At the physical examination she presented with a red oropharynx, although the chest x-ray was normal. The patient was discharged, and amoxicillin and paracetamol were prescribed. Two days later she returned with a persistent fever (38.2°C), cough and dyspnoea. Arterial gases were: Pao2 55 mm Hg, Paco2 34 mm Hg. A pulmonary infiltrate in the right lower lobe had appeared. The patient was hospitalised, the antibiotic was changed to levofloxacin (500 mg/daily) and 24 h later, after nasopharyngeal swaps were positive for influenza H1N1 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the patient was isolated and treatment with oseltamivir (75 mg twice daily) was started. Clinical improvement was observed the following days, except for mild residual cough, and she was discharged from hospital on the fifth day. Three weeks later she came for her outpatient visit and reported progressive dyspnoea and cough. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed and bilateral subsegmental areas of consolidation in a peripheral distribution were found (fig 1A). Lung function test showed a carbon monoxide diffusion capacity of 80% (predicted) with normal lung volumes. Basal arterial gases were: Pao2 105 mm Hg, Paco2 28 mm Hg. An ambulatory flexible bronchoscopy was performed to obtain pulmonary samples. Transbronchial lung biopsies from the right lower lobe were taken by freezing cryoprobe and the histology showed multiple areas of organising pneumonia and alveolar cells with viral cytopathic changes (fig 1B). The patient was treated with prednisone (0.75 mg/kg/day). A month later clinical and radiological improvement was observed.

Figure 1.

(A) Coronal reformation computed tomography image showing organising pneumonia in a perilobular distribution (arrows). (B) High power photomicrograph shows a polypoid plug of fibroblastic tissue within an alveolar space (arrow). Note alveolar cell showing viral cytopathic changes (arrowheads).

Discussion

Organising pneumonia is an inflammatory and fibroproliferative lung reaction leading to a clinico-radiologic-pathological syndrome. It may occur with no detectable cause (cryptogenic) or may be associated with various processes including, among others, infections, drugs, and connective disorders. The clinical picture is usually subacute and may include fever, fatigue, weight loss, cough, dyspnoea, crackles, and can progress to respiratory failure. At imaging, the most typical pattern consists of multiple subpleural consolidations. Open lung biopsy can be necessary to confirm the diagnosis, showing buds of loose connective tissue filling the lung alveoli. In our case, bronchoscopic transbronchial biopsy with a cryoprobe3 was sufficient to confirm the diagnosis. Most patients respond well to moderate doses of prednisone from 1–3 months. Data coming especially from autopsy studies after influenza pandemics describe a large spectrum of lung changes associated with viral pneumonia. Later stages of influenza virus pneumonia can be associated with organising pneumonia with diffuse alveolar damage and fibrosis.4 In a recent article, seven patients with confirmed H1N1 infection were followed according to the radiographic and chest CT findings. The most common alterations were ground glass opacities, with or without areas of consolidation, with predominant peribronchovascular and subpleural distribution, resembling organising pneumonia.5 There have been radiologically suspected cases of organising pneumonia, but no biopsy proven cases, and to our knowledge no histological confirmation of organising pneumonia secondary to H1N1 infection has been reported. Oseltamivir is indicated in patients admitted to hospital with confirmation of influenza A or in patients included in risk groups. In our case, oseltamivir could not prevent the subacute development of organising pneumonia.

Learning points

Although this is a single observation, we highlight that:

Organising pneumonia should also be considered as a possible complication of influenza A (H1N1) infection.

Patients diagnosed with organising pneumonia secondary to H1N1 can benefit from early diagnosis and appropriate specific management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs C Puzo and JM Rodriguez-Arias for their clinical contribution, as well as Drs V Plaza and Professor J Sanchis for their manuscript supervision.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – update 73. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/updates/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louie JK, Acosta M, Winter K, et al.for the California Pandemic (H1N1) Working Group Factors associated with death or hospitalization due to pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection in California. JAMA 2009; 302: 1896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pajares V, Torrego A, Puzo MC, et al. Transbronchial lung biopsies with cryoprobes in diffuse lung parenchymal lung diseases. Arch Bronconeumol 2009doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2009.09.012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol 2008; 3: 449–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajlan AM, Quiney B, Nicolaou S, et al. Swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viral infection: radiographic and CT findings. Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193: 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]