Abstract

NK cells play an important role in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) and in cross talk with dendritic cells (DCs) to induce primary T cell response against infection. Therefore, we hypothesized that blood DCs should augment NK cell function and reduce the risk of leukemia relapse after HCT. To test this hypothesis, we conducted laboratory and clinical studies in parallel. We found that although phenotypically NK cells could induce DC maturation and DCs could in turn increase activating marker expression on NK cells, paradoxically, both BDCA1+ myeloid DCs and BDCA4+ plasmacytoid DCs suppressed the function of NK cells. Patients who received an HLA-haploidentical graft containing larger number of BDCA1+ DCs or BDCA4+ DCs had a higher risk of leukemia relapse and poorer survival. Further experiments indicated that the potent inhibition on NK cell cytokine production and cytotoxicity was mediated in part through the secretion of IL-10 by BDCA1+ DCs and IL-6 by BDCA4+ DCs. These results have significant implications for future HCT strategies.

Keywords: Alloegenic hematopoietic cell transplantation, pediatric leukemia, human NK cell, dendritic cell

INTRODUCTION

NK cells play an important role in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) for leukemia (1–4). It has been demonstrated that donor NK cells may promote engraftment, prevent graft-versus host disease, control infections, and reduce the risk of leukemia relapse. We and others have demonstrated that NK cell alloreactivity is affected by many determinants, including donor versus recipient KIR ligand compatibility, KIR-HLA receptor-ligand mismatch, and the milieu of cytokine such as IL-12 and IL-18 (1, 5–7). Furthermore, the potency of NK activity appears to be augmented by a lymphopenic environment, especially T-cell lymphopenia because T-cell alloreactivity dominates that of NK cells (8).

Besides the interaction with T-cells, we began to investigate the interactions of human NK cells with dendritic cells (DCs) and examined their effects on patient outcomes after HCT. Blood DCs are not a single cell type but consist of several distinct subsets, including myeloid and lymphoid/plasmacytoid DC (pDC) that are derived from common myeloid and lymphoid progenitors, respectively (9, 10). The interactions between DCs and NK cells have been well documented (11–15). For instance in infection, it is well known that DCs and NK cells cross talk to induce primary T cell response (14, 16). Both NK cells and DCs are part of the innate immune response system and are equipped with a large array of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that allow the recognition of different pathogens (17). Toll like receptors (TLRs) are PRRs that upon recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) can induce triggering of innate immune response (18). When immature DCs (iDCs) are activated by TLRs ligands, they differentiate into mature DCs (mDCs) that express high levels of MHC class I and MHC class II antigens as well as costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86), which are required for stimulation of naïve T cells (19, 20). Because HCT setting is characterized by an inflammatory environment with abundant PAMPs derived from endogenous pathogens and host tissue damaged by the high-dose chemotherapy and radiation (21–23), we hypothesized that DCs should augment NK cell function and thereby reduce the risk of leukemia relapse after transplantation. To test this hypothesis, we conducted laboratory and clinical studies in parallel to examine the effects of blood DC subsets on NK cells in HCT setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies, TLR ligands, and cell lines

The following fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against human antigens were obtained from BD Pharmigen: CD3-APC, CD8-PECy7, CD11c-APC, CD14-APCCy7, CD19-APCCy7, CD20-PE, CD45-FITC, CD69-FITC, CD80-FITC, CD81-PE, CD83-PECy5, CD123-PE, NKG2D-APC, IFN-γ-FITC, IFN-γ-PECy7, Lin markers cocktail-FITC, Phospho-Zap70 (Y319) / Syk (Y352)-PE, and Phospho-SLP-76 (pY128)-PE. Fluorochrome-labeled mAbs CD25-PE, CD9-FITC and CD19-PE were obtained from DAKO. Fluorochrome-labeled mAbs CD3-ECD, CD45-ECD, CD56-APC, CD86-PE, and HLA DR-ECD were obtained from Beckman Coulter. Fluorochrome-labeled mAbs CD1c (BDCA1)-PE and CD304 (BDCA4)-APC were obtained from Miltenyi Biotec.

A-Class CpG ODN 2216 5`-ggGGGAGCATGCTGgggggG-3` as TLR9 ligand was provided by Hartwell Center for Bioinformatics and Biotechnology at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma 0127:B8) was used as TLR4 ligand.

K562 leukemia cell lines were used as targets for NK cell natural cytotoxicity assays. Luciferase transduced neuroblastoma cell line (NB1691luc) was kindly provided by Dr A. Davidoff (St Jude Children´s Research Hospital) and was used as the target in a quantitative in vivo mouse model.

Isolation and culture of NK cells and DC subsets

NK cells were magnetically isolated from nonmobilizied apheresis products of healthy donor using the AutoMACS machine and NK cell isolation kit from Miltenyi Biotec following the manufacturer’s specifications. From each 1–2×108 peripheral blood mononuclear cell product, we typically obtained between 5 to 15 ×106 cells with a purity of always >95% CD56+CD3- cells. Donor HLA typing was not performed.

BDCA1+ myeloid DCs and BDCA4+ pDCs were magnetically isolated using the AutoMACS machine and Human CD1c (BDCA1) dendritic cell isolation kit and CD304 (BDCA-4/Neuropilin-1) kits from Miltenyi Biotec following the manufacturer´s specifications. Starting with 2–8×109 peripheral blood mononuclear cells, between 0.5–5×106 cells were typically obtained after the isolation procedures ending with a purity always >95% for BDCA4+ cells and >90% for BDCA1+ cells. High levels of expression of TLR9 in purified BDCA4+ cell products and TLR4 in purified BDCA1+ products were confirmed by RTPCR.

Freshly purified NK cells were cocultured with or without DC subsets in a cell ratio of 2:1 overnight with or without adding LPS 100 ng/ml or a-CpG 10 µg/ml. Cultures were performed in complete culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 ng/ml streptomycin, and 2mM/L-glutamine) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air, with no addition of exogenous cytokines such as IL-2 or IL-15. DC maturation was assessed using CD80, CD83 and HLA-DR mAbs. CD69 and CD25 were used to assess NK cell activation status.

RT-PCR and real-time PCR for TLR

RNA was isolated with RNAeasy (Quiagen 2001). DNA was removed by digestion with 5 U deoxyribonuclease I (Boehringer) for 30 min at 37° C. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed with oligo-dT primer (Omniscript, Quiagen 2004). The PCR reaction volume was 50 µl, containing 0.5 µM of each primer, 200 µM of each dNTP, and 2.5 units HotStarTaq (Quiagen 2005). The following sets of primers were used: TLR4 (F: 5’-CTGCAATGGATCAAGGACCA-3’, R: 5’-TTATCTGAAGGTGTTGCACATTCC-3’) and TLR9 (F: 5’-TGAAGACTTCAGGCCCAACTG-3’, R: 5’- TGCACGGTCACCAGGTTGT-3’). A GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (PerkinElmer/Applied Biosystems) was used with an initial denaturation step of 95° C for 15 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94° C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s (annealing temperature), 72° C for 1 min (extension temperature), and a final elongation step of 72° C for 7 min.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) was performed by using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector Systems (Applied Biosystems) and the SYBR Green I Dye assay chemistry, as suggested by the manufacturer. Briefly, all reactions were performed with 2 µL (80 ng) of cDNA, 12.5 µL of SYBR GREEN PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), and 0.5 µM forward and reverse primers in a final reaction volume of 25 µl. A water control and melting curve analysis were always performed to confirm the specificity of the PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control to normalize the difference in the amount of cDNA contained in each initial reaction. Reactions were incubated for 2 min at 50°C, denatured for 10 min at 95 °C, and subjected to 40 two-step amplification cycles with annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min followed by denaturation at 95°C for 15 s.

Phospho-protein assay of NK cells stimulated with TLR ligands

NK cell signaling after direct TLR ligand stimulation was determined by multi-parameter intracellular phospho-proteins assay using flow cytometry. In brief, 1×106 unstimulated NK cells or NK cells stimulated with LPS or a-CpG were fixed after different time points (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, 240, 270, 300 seconds, 15, 30 minutes and 8 hours) by adding 4% formaldehyde directly into the culture medium to obtain a final concentration of 2% formaldehyde. NK cells were incubated in fixative for 10 min at ambient temperature and pelleted. They were then permeabilized by resuspending with vigorous vortexing in 500 µl ice-cold MeOH per 106 and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. After that, cells were washed twice in staining media (PBS containing 1% BSA) and then resuspended in staining media at 0.5–1×106 cells per 100 µl. Fluorophore-specific mAbs were added and incubated for 15–30 min at ambient temperature. The cells were washed with 15 volumes of staining media and pelleted. Finally, samples were resuspended in 100 µl staining media and analyzed. At the same time points, intracellular IFN-γ staining was analyzed with mouse antihuman-IFNγ clone 4S.B3.

Cytokine Array

Purified NK cells (2×105), with or without DC subsets (1×105), were cultured in 48-well plates in 0.4 ml of complete culture medium and incubated with or without 10 µg/ml CpG or 100 ng/ml LPS at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 15 h of incubation, culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for cytokine production by ELISA using the Bioplex Protein Array system (BioRad) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Data analyses of all assays were performed with the Bio-Plex Manager software.

Cytotoxicity assays

Natural cytotoxicity of NK cells was assessed in a conventional 2-hour europium-TDA release assay (Perkin-Elmer Wallac, Turku, Finland)(24). The following formulas were used to calculate spontaneous and specific cytotoxicity:

% Specific release = (Experimental release − spontaneous release) / (Maximum release − spontaneous release) × 100.

% Spontaneous release = (Spontaneous release − background) / (Maximum release − background) × 100.

NK cell suppression by IL-6 and IL-10

Purified NK cells were incubated at 37°C with various concentrations of recombinant human IL-6 or recombinant human IL-10 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cytotoxic function of NK cells was determined using standard europium- release assay as described above after 48 hours of incubation.

Mouse model of metastatic neuroblastoma

Six- to 8-week-old NOD-scid IL2Rgnull mice were sublethally irradiated with 200 cGy and 24 hours later they were injected intravenously with NB-1691luc 5×105 neuroblastoma cells. Intravenous NK cellular therapy began 7 days after the injection of tumor cells and was performed once a week for 3 weeks. In three independent experiments (15 mice per group), we compared untreated mice (control group) with mice receiving 1× 106 NK cells stimulated overnight with 10 µg/ml a-CpG (NK+CpG group), or mice receiving 1× 106 NK cells and 5× 105 BDCA4 in coculture overnight with 10 µg/ml a-CpG (NK+CpG+BDCA4 group). Bioluminescence imaging was performed after the initiation of NK cell therapy on days 7, 14, and 21 after i.p. injection of 200 µl of luciferin dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 15 mg/ml. Between 7 and 10 minutes after administration of substrate, animals were anesthetized using isofluorane and transferred to the Xenogen IVIS©-200 Imaging system (Xenogen Corporation, Hopkinton, MA). Images were captured at varied exposures and analysis performed using Xenogen Living Image® Software (version 2.50). For BLI plots, a rectangular region of interest (ROI) encompassing the entire thorax and abdomen was applied for each mouse and total flux (photons/second (p/s)) calculated in ventral and prone positions at different exposures (1, 10, 60 and 120 seconds). This value was scaled to a comparable background value (from a non-tumor bearing, luciferin injected control mouse). All experiments were conducted following the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees according to criteria outlined in the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

HCT for hematologic malignancies

Patients received either total body irradiation (TBI, 12Gy) with Thiotepa (10mg/kg) and cyclophosphamide (120mg/kg), or a non-TBI regimen with fludarabine (150mg/m2), thiotepa (10mg/kg), and melphalan (140mg/m2). Post-HCT, patients required only single agent GVHD prophylaxis with cyclosporine or mycophenolate, because all the grafts were depleted of CD3+ cells by immunomagnetic method using the CliniMACs system (Miltenyi). The number of BDCA1+ cells and BDCA4+ cells in the parental grafts after T-cell depletion were measured by flow cytometry analysis.

Statistical analyses

The risk of leukemia relapse and death after HCT were estimated and compared by using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test among patients who were categorized in tertiles based on the number of donor BDCA1+ cells (<0.5, 0.5–0.9, and >1.0×108) or BDCA4+ cells (<1.4, 1.5–2.5, and >2.5×108) in the grafts. Other risk factor analyses included age, primary diagnosis, degree of HLA match, conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis, history of GVHD, and remission status. The standard risk category consisted of patients with AML, ALL, or NHL in first or second complete remission. The high-risk category included patients in third or subsequent remission, in relapse, or with myelodysplastic syndrome.

The effects of blood DCs on the cytokine production and cytotoxicity of NK cells in vitro were evaluated by Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The dose-response suppressive effects of IL-6 and IL-10 on NK cell cytotoxicity were analyzed by trend test. Difference in total flux in bioluminescence was compared using repeated measures ANOVA.

RESULTS

Phenotypic changes in coculture of NK cells and blood DC subsets

Highly purified CD56+3- NK cells were co-localized in our in vitro culture system with either BDCA1+ myeloid DCs or BDCA4+ pDCs for 24 hours in cell ratio of 2:1. We observed an increase in surface expression in both DC subsets of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80), maturation markers (CD83), and MHC Class II (HLA-DR); all of these changes suggested the blood DCs were undergoing maturation in the in vitro system. In turn, both DC subsets were able to activate NK cells phenotypically, as indicated by the induction of CD69 and CD25 expression on NK cells.

Suppression of TLR-ligand effect on NK cell by blood DC

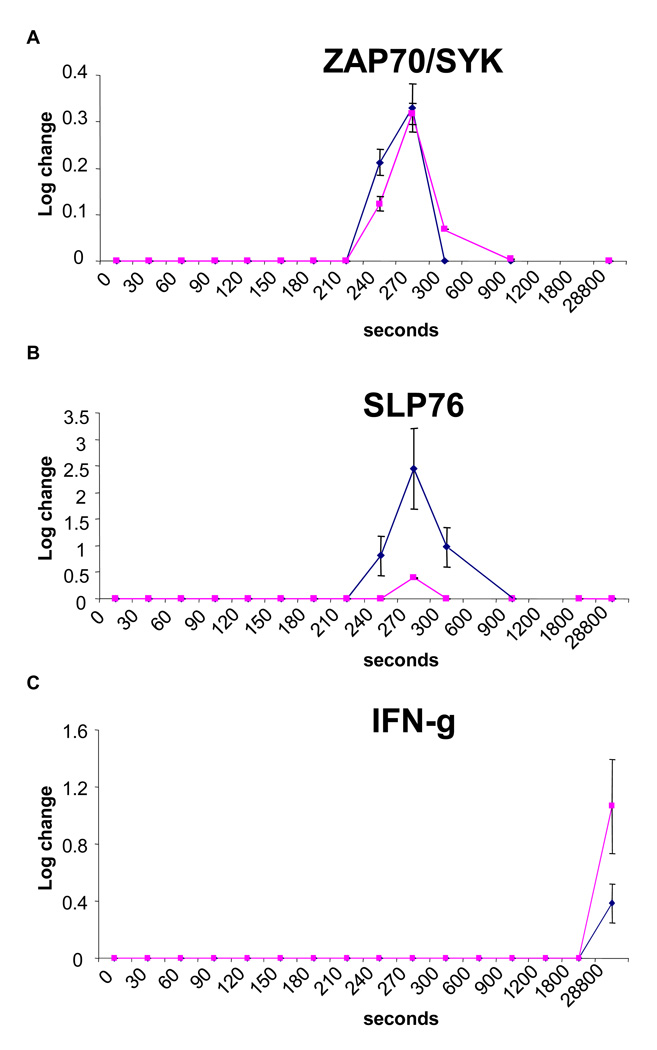

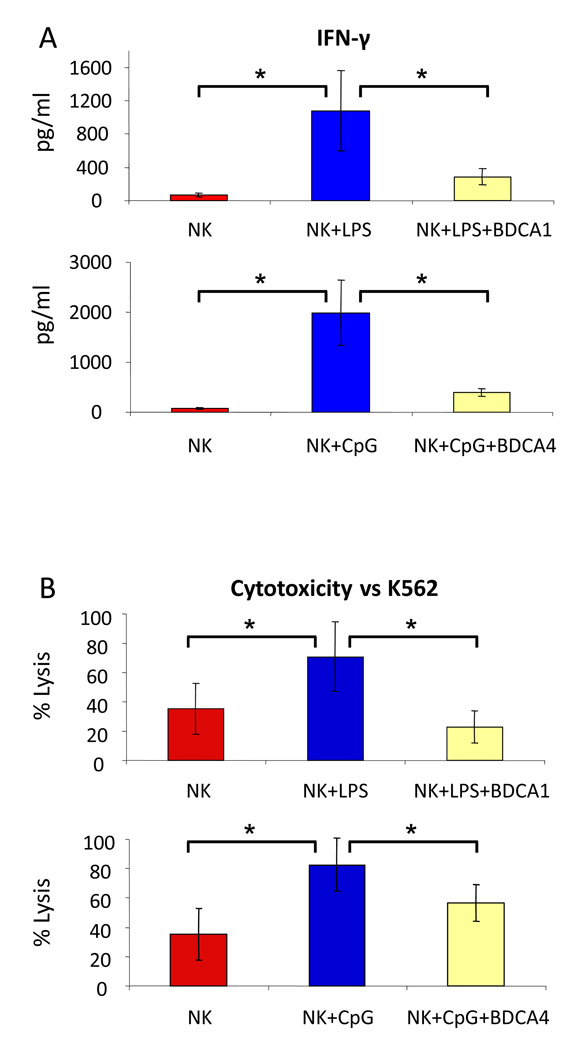

Base on the phenotypic changes described above, we hypothesized that human blood DCs should augment the function of NK cells in the presence of TLR ligands in the HCT setting. To test this hypothesis, we examined the direct effect of TLR ligands on NK cells and the secondary effects through DCs. We found that both TLR4 and TLR9 were expressed on highly purified NK cells as determined by RT-PCR assay, but the level of mRNA did not change with ligand exposure as demonstrated by RQ-PCR analysis (mean delta CT 7.9±1.4 vs. 7.7±1.1 for TLR4 and 5.8±1.7 vs. 5.4±1.4 respectively, all p>0.48). Importantly, the TLRs were functional as demonstrated by positive ZAP70/SYK and SLP76 signaling and a rise in production of IFN-γ (Figure 1). Furthermore, TLR ligands increased the secretion of IFN-γ by NK cells (Figure 2A) and enhanced the cytotoxicity against K562 cells (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, both BDCA1+ myeloid DC and BDCA4+ pDC strongly suppressed the NK cell production of IFN-γ induced by TLR ligands (Figure 2A). In addition, BDCA4+ pDC were able to reduce the stimulation effect of a-CpG on NK cytotoxicity against K562 cells, whereas BDCA1+ myeloid DC could completely offset the effect of LPS (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. TLR signaling in purified NK cells.

Phosphorylation of (A) ZAP70/SYK and (B) SLP76 in purified NK cells after incubation with 10 µg/ml of a-CpG (blue) or 100 ng/ml of LPS (pink), with resultant increased in (C) IFN-γ production. Data are expressed as means ± SEM of three different experiments.

Fig 2. Effects of TLR ligands and blood DC subsets on IFN-γ secretion and natural cytotoxicity of NK cells.

(A) IFN-γ secretion by unstimulated NK cells (NK), NK cells stimulated overnight with 100 ng/ml of LPS (NK+LPS) or 10 µg/ml of a-CpG (NK+CpG), and NK cells stimulated overnight with one of these two TLR ligands in the presence of BDCA1+ myeloid DCs (NK+LPS+BDCA1) or BDCA4+ pDCs (NK+CpG+BDCA4) in a starting 2:1 cell ratio (no change in cell number or ratio thereafter was observed overnight). Results are expressed as means ± SEM from three independent experiments. (B) Cytotoxicity against K562 cells (NK:K562 cell ratio were always 8:1) by unstimulated NK cells (NK), NK cells stimulated overnight with 100 ng/ml of LPS (NK+LPS) or 10 µg/ml of a-CpG (NK+CpG), and NK cells stimulated overnight with one of these two TLR ligands in the presence of BDCA1+ myeloid DCs (NK+LPS+BDCA1) or BDCA4+ pDCs (NK+CpG+BDCA4) in a NK:DC cell ratio of 2:1. After cocultured, NK cells were not further purified. Results are expressed as means ± SEM from three independent experiments. * P < 0.05.

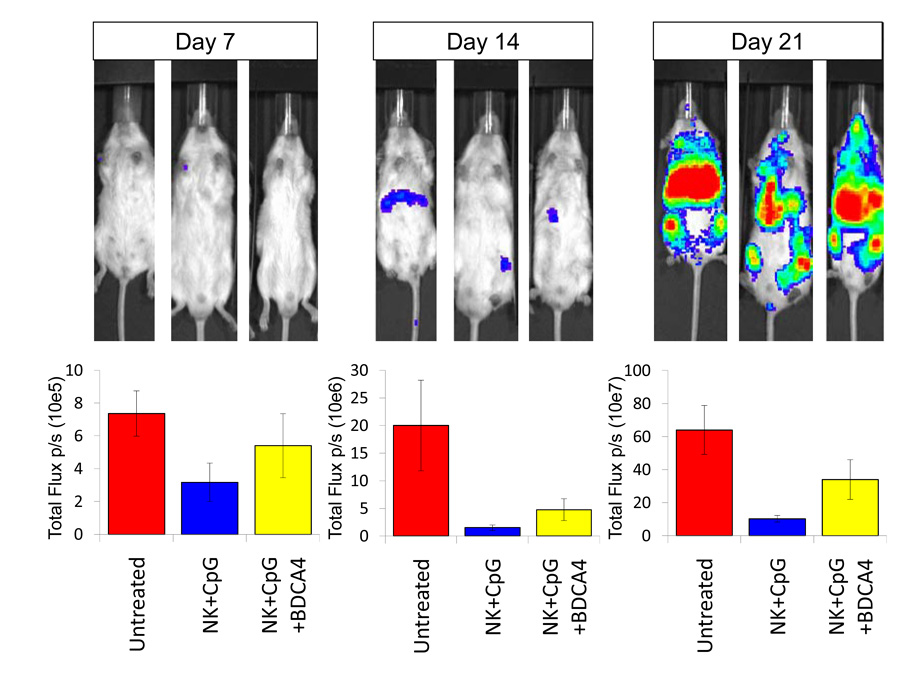

We then extended our investigation to an in vivo model to examine whether the modest suppressive effect of BDCA4+ pDC on TLR ligand stimulated NK cells in vitro might be clinically meaningful. We found that BDCA4+ pDC were indeed able to suppress the anti-tumor effect of CpG activated NK cells (P<0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Suppressive effect of BDCA4+ cells on the antitumor response of NK cells.

Quantitative ventral photon counting analysis on Day 7, 14, and 21 after the initiation of NK cell therapy in a metastatic neuroblastoma mouse model. Animals either received no treatment (Untreated), or received treatment with NK cells stimulated overnight with 10 µg/ml of a-CpG (NK+CpG), or NK cells stimulated with a-CpG in the presence of BDCA4+ pDCs (NK+CpG+BDCA4) in a 2:1 cell ratio. Results are representative of and summarized from three independent experiments (means ± SD) at various time points after receiving NK cellular therapy.

Higher risk of relapse and poorer survival in patients with childhood leukemia receiving higher dose of blood DCs

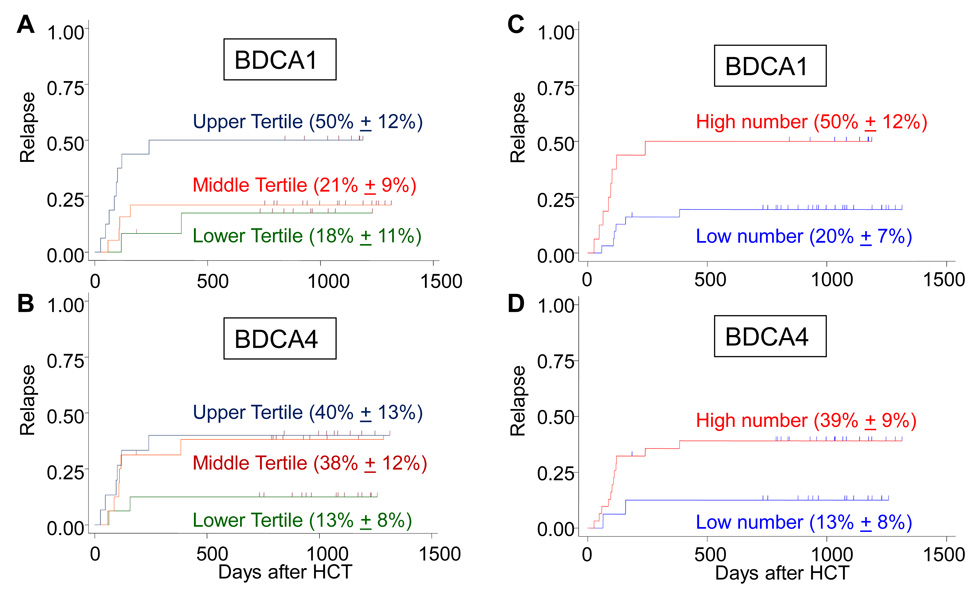

To examine the effects of DC subsets on patient outcomes, we studied 47 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (n=17), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=25), or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=5), who received an HCT from a HLA-haploidentical parental donor. We measured the number of DC in the patient’s graft prospectively and categorized them into tertiles based on the DC content. We found that those patients who had in their graft a higher number of BDCA1+ myeloid DC (upper tertile) or BDCA4+ pDC (upper two tertiles) had poorer survival because of increased incidence in leukemia relapse (Figure 4). No other factors were found to be statistically significant, including age, primary diagnosis, risk group, degree of HLA matching, conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis, or history of GVHD (all P>0.16). The number of BDCA1+ or BDCA4+ DCs in the graft has no effect on transplant-related mortality (P>0.36).

Figure 4. Cumulative risk of leukemia relapse after HCT.

The risk of leukemia relapse after transplant was evaluated based on the graft’s DC content in tertiles: (A) BDCA1+ cells (<0.5, 0.5–0.9, and >1.0×108) or (B) BDCA4+ cells (<1.4, 1.5–2.5, and >2.5×108). Those patients who had received a hematopoietic graft containing (C) the upper tertile of BDCA1+ myeloid DCs or (D) the upper two tertiles of BDCA4+ pDCs (high number) had a higher risk of relapse when compared with those who received less DCs (low number), P<0.05.

Inhibition of NK cells by DCs through IL-6 and IL-10

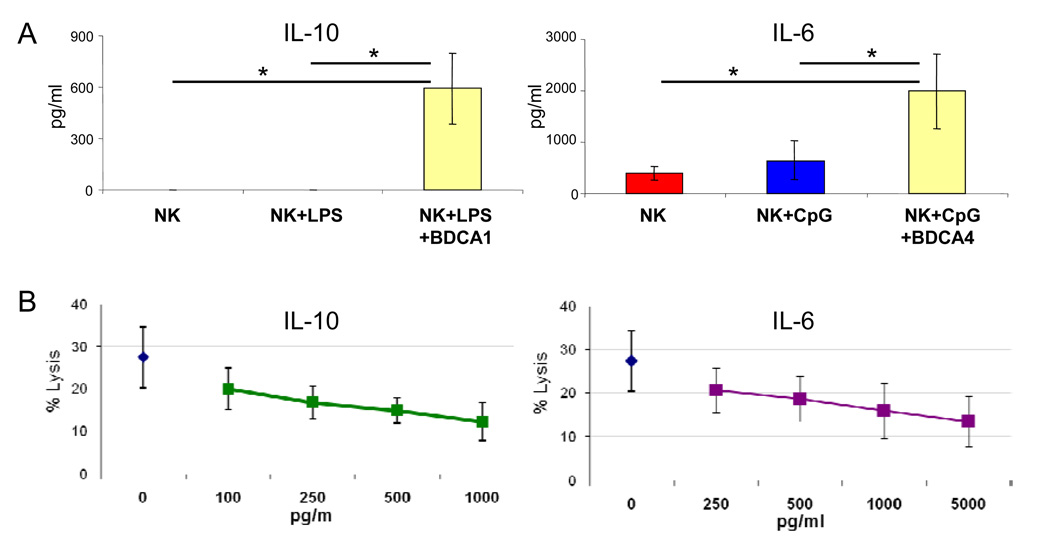

To investigate the mechanisms of the suppressive effects of blood DCs on NK cells activated by TLR ligands, we examined the cytokine profile of the in vitro co-cultures. We found that in the presence of BDC1+ myeloid DC or BDC4+ pDC, there was a large amount of IL-10 (mean 600 pg/ml) or IL-6 (mean 2,000 pg/ml), respectively (Figure 5A). Incubation of NK cells with recombinant IL-6 or IL-10 at these cytokine concentrations confirmed a dose-dependent suppressive effects on the cytotoxic function of NK cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Role of IL-6 and IL-10.

(A) IL-10 and IL-6 levels in the supernatant of cell cultures including unstimulated NK cells (NK), NK cells stimulated overnight with 100 ng/ml of LPS (NK+LPS) or 10 µg/ml of a-CpG (NK+CpG), and NK cells stimulated with these two TLR ligands in the presence of BDCA1+ myeloid DCs (NK+LPS+BDCA1) or BDCA4+ pDCs (NK+CpG+BDCA4) in a 2:1 cell ratio. Results are expressed as means ± SEM from three independent experiments. * P < 0.05 (B) Suppressive effect of IL-6 and IL-10 on natural cytotoxicity of NK cells. Incubation of purified NK cells with soluble IL-10 or IL-6 (with no DCs or TLR ligands) for 48 hours resulted in reduction of natural cytotoxicity against K562 cells (E:T; 2:1) in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05 for the two highest concentrations of IL-6 and IL-10 when compared with no cytokines, and for dose-response as analyzed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test and trend test).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to prove that blood DCs augmented NK cell function and thus favored the clinical activity of NK cells against acute myeloid leukemia (5) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (7). Our hypothesis was based on the large body of literatures supporting a critical role of DC and NK cell cross talk in the control of infection (18, 25–27). Surprisingly, we found that although phenotypically NK cells could induce DC maturation and DCs could in turn increase the expression of activating markers in NK cells as described by other investigators, paradoxically, both blood BDCA1+ myeloid DC and BDCA4+ pDC suppressed the function of NK cells in both in vitro assays and in vivo mouse models when TLR ligands were used to mimic the microbe-associated inflammatory environment in allogeneic HCT (28). The clinical relevance of these finding is underscored by our observation that patients who received an HLA-haploidentical graft containing large number of BDCA1+ myeloid DC and BDCA4+ pDC had a high risk of leukemia relapse. Detailed biological studies reveal that DC were potent inhibitor of both NK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine production and were mechanistically mediated in part through IL-10 or IL-6. These findings have significant implications for future HCT strategies.

NK cell function is tightly regulated by a balance of signals from inhibitory and activating receptors. The “missing-self” hypothesis suggests that NK cell specificity is determined by the interaction between NK cell inhibitory receptors and target cell MHC class I expression (29). Even in the absence of target cell MHC, however, most activating receptor-ligand interactions are insufficient to induce cytotoxicity by resting peripheral-blood NK cells (30). Except for CD16, pre-activation of NK cells is required to generate sufficient signal for cytolytic granule polarization and degranulation (31, 32). NK cell may be pre-activated by many non-ADCC factors such as cytokines or pathogen-derived substances (30). TLR ligands are pathogen-derived substances that can activate NK cell indirectly through accessory cells (33, 34) or directly through TLR expressed on NK cells (35–37). It remains controversial on the level of expression of each of the ten TLR family members on human NK cells, and their ability to directly activate NK cell. For example, some studies failed to show the expression of TLR9 on human NK cells and direct activation by its ligands (33, 34), whereas others demonstrated its expression and function (36, 38). TLR3 was found to be expressed at higher level than TLR1 in some studies (35), but a reverse order was observed by others (33). Furthermore, some found significant TLR4 expression on human NK cells and its ability to directly trigger cytokine production and cytotoxicity (35, 37); however, others did not observed any significant TLR4 expression or direct function (33, 34). Differences in NK cell gating or purification strategy, culture condition, induction status, and the amount or type of ligand used may explain the differences between previous reports (34, 38, 39). In our study, we found that human NK cells expressed TLR9 in addition to TLR4, as evidenced by the presence of mRNA in highly purified NK cells. More importantly, we showed that they were functionally responsive directly to TLR ligands in the absence of DCs, and both TLR-ligands were capable of stimulating NK cells with resultant signaling through ZAP70/Syk and SLP 76 phosphorylation. The end results were activation of NK cells to produce IFN-γ and increased killing of target cells both in vitro and in vivo. These results highlight the potential of TLR ligand-activated NK cells in cancer immunotherapy. Clinical scale isolation of NK is now feasible with no contamination of DC (40, 41); thus, NK cells stimulated ex vivo by TLR ligand may be used for cancer treatment. In this regard, recent studies suggested that TLR ligands may improve the efficacy of immunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma by enhancing NK cells and T cells and by altering the tumor microenvironment in angiogenesis (42, 43).

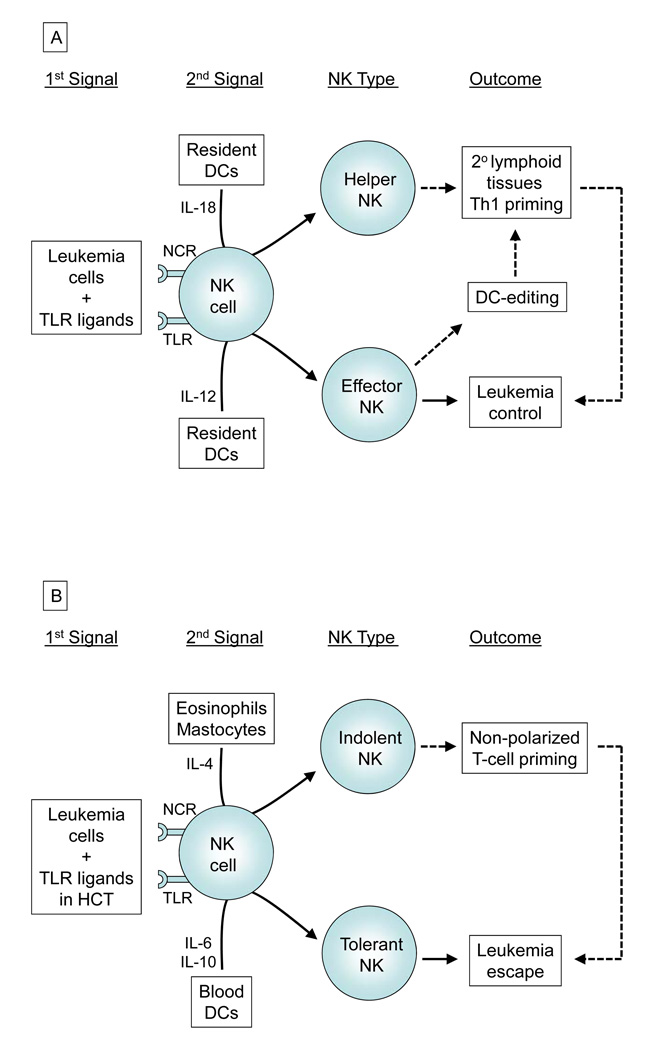

Full priming of human NK cells in peripheral tissue require both the engagement of activating receptors and the presence of activating cytokines released by DC (44). Colocalization of NK cells with both monocyte-derived DCs and pDCs in inflamed tissue is in part mediated by chemerin (45). In a “two-signal” model (44, 46), functionally and phenotypically divergent types of NK cells may be generated after receiving a first signal from tumor cells or via TLRs, and then a second signal delivered through various cytokines released by different immune cells (Figure 6). In the classical model of viral infection, IL-12 produced by peripheral tissue-resident DCs favors the development of CD25+CD69+ “effector” NK cells, which in turn promote optimal maturation of DCs characterized by upregulation of MHC, CCR7, CD80, and CD86 (47). The mature DCs then migrate to the secondary lymphoid tissues to promote Th1 polarization. Those inappropriately primed DC in the inflamed tissue will be killed by the effector NK cells (termed NK-mediated editing). Alternatively under the influence of IL-18, NK cells may acquire a “helper” phenotype with de novo expression of CCR7, thus enabling them to be responsive to CCL19/21. These helper NK cells may then migrate to the secondary lymphoid tissues themselves, and work together with DCs to release large amount of IFN-γ for T cell priming (48, 49).

Figure 6. Two-signal model in HCT for leukemia.

In the presence of leukemia cells and TLR ligands (1st signal), various immune cells may provide NK cells a different 2nd signal (A) towards “effector” and “helper” phenotype, or (B) towards “indolent” and “tolerant” phenotype. The NK cell effects on leukemia may be direct (solid arrows), especially in T-cell depleted HCT setting as described herein, or mediated through T-cell priming (dotted arrows).

Recent studies, however, have demonstrated that not all interactions among NK cells and other innate immune cells may result in induction of NK cell priming and Th1 polarization. For example, exposure of NK cells to IL-4 released by mastocytes and eosinophils may lead NK cells towards an “indolent” NK phenotype and impair NK-mediated DC editing (Figure 6) (50). In this study, we extend the two-signal model further by demonstrating for the first time that circulating myeloid DCs and pDCs, unlike peripheral tissue-resident DCs, may favor an IL6 or IL10-rich milieu respectively, to tolerize NK cells and promote tumor cell growth. Though the source of these 2 cytokines has not been established, the presence of either BDCA1+ or BDCA4+ DCs clearly resulted in a significant decrease in TLR ligand-induced production of IFN-γ and a reduction in killing of target cells by NK cells in vitro and in vivo. Both IL-6 and IL-10 are pleiotropic cytokine with dual immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory properties as well as tumor-promoting and tumor-inhibitory effects (51, 52). For instance, IL-6 is considered an activator of acute phase response and a lymphocyte stimulatory factor (53), but it can also block neutrophil accumulation, DC development, NF-κB binding activity, CCR7 expression, and mixed lymphocyte reaction (54–56). On the other hand, IL-10 was originally termed cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor and suppresses NF-κB through STAT3 in DCs and CD4+ T cells, but paradoxically it can also activate NF-κB and AP-1 in CD8+ T cell to increase its cytotoxicity (51, 57). Because the effects of blood DCs on NK cells is suppressive as demonstrated herein and are mechanistically mediated through IL-6 and IL-10, our findings should encourage further study of novel medical therapy to block the secretion of these 2 cytokines or to neutralize their activity to improve NK therapeutic potential. Clinical grade antibodies are now available for both IL-6 and IL-10 (51, 58).

Our finding that patients who received an HLA-haploidentical graft containing larger number of BDCA1+ DC and BDCA4+ DC had a higher risk of leukemia relapse and poorer survival rate should have immediate implications in clinical HCTs. First, it provides a novel prognostic factor in the management of haploidentical HCT patients. Second, the data suggest that DC depletion from the donor graft should be considered in haploidentical HCT for leukemia, as blood DCs may not only inhibit NK cells, but also contain some circulating tolerogenic DC subsets (59, 60). DC depletion can be accomplished by directly removing DCs from the hematopoietic graft, or indirectly through positive selection of stem cells using markers such as CD133 or CD34 which are commonly used in the clinic (61).

In summary, our study provides fundamental insights into the biology of blood DC subsets and NK cells in the presence of TLR ligands as in the setting of HCTs. Laboratory and clinical data provide strong evidence for a dominant suppressive effect of BDCA1+ myeloid DCs and BCDCA4+ pDCs. These results should have significant implications for future medical therapies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Drs. Thasia Leimig, Miguel A. Sanjuan, and Christopher Calabrese for their technical assistance and advice. This work was supported in part by research grants from NIH P30 CA-21765, the Assisi Foundation of Memphis, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). A. P-M was supported by National Health Service of Spain grant FIS CM-04/00011.

Abbreviations

- HCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Velardi A, Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, et al. Clinical impact of natural killer cell reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:489–503. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanier LL. The role of natural killer cells in transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:626–631. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valiante NM, Parham P. Natural killer cells, HLA class I molecules, and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1997;3:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy WJ, Koh CY, Raziuddin A, Bennett M, Longo DL. Immunobiology of natural killer cells and bone marrow transplantation: merging of basic and preclinical studies. Immunol Rev. 2001;181:279–289. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1810124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung W, Iyengar R, Triplett B, et al. Comparison of killer Ig-like receptor genotyping and phenotyping for selection of allogeneic blood stem cell donors. J Immunol. 2005;174:6540–6545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung W, Iyengar R, Turner V, et al. Determinants of antileukemia effects of allogeneic NK cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:644–650. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe EJ, Turner V, Handgretinger R, et al. T-cell alloreactivity dominates natural killer cell alloreactivity in minimally T-cell-depleted HLA-non-identical paediatric bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:323–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald KP, Munster DJ, Clark GJ, Dzionek A, Schmitz J, Hart DN. Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood. 2002;100:4512–4520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa F, Niiro H, Iino T, et al. The developmental program of human dendritic cells is operated independently of conventional myeloid and lymphoid pathways. Blood. 2007;110:3591–3660. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Fuchs A, Colonna M, Caligiuri MA. NK cell and DC interactions. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez NC, Lozier A, Flament C, et al. Dendritic cells directly trigger NK cell functions: cross-talk relevant in innate anti-tumor immune responses in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:405–411. doi: 10.1038/7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcenaro E, Dondero A, Moretta A. Multi-directional cross-regulation of NK cell function during innate immune responses. Transpl Immunol. 2006;17:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walzer T, Dalod M, Robbins SH, Zitvogel L, Vivier E. Natural-killer cells and dendritic cells: "l'union fait la force". Blood. 2005;106:2252–2258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson JL, Heffler LC, Charo J, Scheynius A, Bejarano MT, Ljunggren HG. Targeting of human dendritic cells by autologous NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:6365–6370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Della Chiesa M, Sivori S, Castriconi R, Marcenaro E, Moretta A. Pathogen-induced private conversations between natural killer and dendritic cells. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature. 2000;406:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andoniou CE, van Dommelen SL, Voigt V, et al. Interaction between conventional dendritic cells and natural killer cells is integral to the activation of effective antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1011–1019. doi: 10.1038/ni1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis e Sousa C. Toll-like receptors and dendritic cells: for whom the bug tolls. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor PA, Ehrhardt MJ, Lees CJ, et al. TLR agonists regulate alloresponses and uncover a critical role for donor APCs in allogeneic bone marrow rejection. Blood. 2008;112:3508–3516. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke KR, Gerbitz A, Crawford JM, et al. LPS antagonism reduces graft-versus-host disease and preserves graft-versus-leukemia activity after experimental bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1581–1589. doi: 10.1172/JCI12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blazar BR, Krieg AM, Taylor PA. Synthetic unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanosine oligodeoxynucleotides are potent stimulators of antileukemia responses in naive and bone marrow transplant recipients. Blood. 2001;98:1217–1225. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bari R, Bell T, Leung WH, et al. Significant functional heterogeneity among KIR2DL1 alleles and a pivotal role of arginine 245. Blood. 2009;114:5182–5190. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews DM, Scalzo AA, Yokoyama WM, Smyth MJ, Degli-Esposti MA. Functional interactions between dendritic cells and NK cells during viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:175–181. doi: 10.1038/ni880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan H, Moretto M, Bzik DJ, Gigley J, Khan IA. NK cells enhance dendritic cell response against parasite antigens via NKG2D pathway. J Immunol. 2007;179:590–596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, Trinchieri G. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:327–333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penack O, Holler E, van den Brink MR. Graft-versus-host disease: regulation by microbe-associated molecules and innate immune receptors. Blood. 115:1865–1872. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karre K. Natural killer cell recognition of missing self. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:477–480. doi: 10.1038/ni0508-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryceson YT, March ME, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Activation, coactivation, and costimulation of resting human natural killer cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:73–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryceson YT, March ME, Barber DF, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Cytolytic granule polarization and degranulation controlled by different receptors in resting NK cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1001–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryceson YT, March ME, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood. 2006;107:159–166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, et al. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorski KS, Waller EL, Bjornton-Severson J, et al. Distinct indirect pathways govern human NK-cell activation by TLR-7 and TLR-8 agonists. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1115–1126. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalifour A, Jeannin P, Gauchat JF, et al. Direct bacterial protein PAMP recognition by human NK cells involves TLRs and triggers alpha-defensin production. Blood. 2004;104:1778–1783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivori S, Falco M, Della Chiesa M, et al. CpG and double-stranded RNA trigger human NK cells by Toll-like receptors: induction of cytokine release and cytotoxicity against tumors and dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10116–10121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403744101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauzon NM, Mian F, MacKenzie R, Ashkar AA. The direct effects of Toll-like receptor ligands on human NK cell cytokine production and cytotoxicity. Cell Immunol. 2006;241:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourke E, Bosisio D, Golay J, Polentarutti N, Mantovani A. The toll-like receptor repertoire of human B lymphocytes: inducible and selective expression of TLR9 and TLR10 in normal and transformed cells. Blood. 2003;102:956–963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartmann G, Weeratna RD, Ballas ZK, et al. Delineation of a CpG phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotide for activating primate immune responses in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:1617–1624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iyengar R, Handgretinger R, Babarin-Dorner A, et al. Purification of human natural killer cells using a clinical-scale immunomagnetic method. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:479–484. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leung W, Iyengar R, Leimig T, Holladay MS, Houston J, Handgretinger R. Phenotype and function of human natural killer cells purified by using a clinical-scale immunomagnetic method. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:389–394. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0609-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spaner DE, Masellis A. Toll-like receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:53–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Link BK, Ballas ZK, Weisdorf D, et al. Oligodeoxynucleotide CpG 7909 delivered as intravenous infusion demonstrates immunologic modulation in patients with previously treated non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Immunother. 2006;29:558–568. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211304.60126.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcenaro E, Della Chiesa M, Pesce S, Agaugue S, Moretta A. The NK/DC complot. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;633:7–16. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-79311-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parolini S, Santoro A, Marcenaro E, et al. The role of chemerin in the colocalization of NK and dendritic cell subsets into inflamed tissues. Blood. 2007;109:3625–3632. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mailliard RB, Son YI, Redlinger R, et al. Dendritic cells mediate NK cell help for Th1 and CTL responses: two-signal requirement for the induction of NK cell helper function. J Immunol. 2003;171:2366–2373. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moretta A. Natural killer cells and dendritic cells: rendezvous in abused tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:957–964. doi: 10.1038/nri956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mailliard RB, Alber SM, Shen H, et al. IL-18-induced CD83+CCR7+ NK helper cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:941–953. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, et al. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcenaro E, Della Chiesa M, Bellora F, et al. IL-12 or IL-4 prime human NK cells to mediate functionally divergent interactions with dendritic cells or tumors. J Immunol. 2005;174:3992–3998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vicari AP, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-10 in viral diseases and cancer: exiting the labyrinth? Immunol Rev. 2004;202:223–236. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knupfer H, Preiss R. Significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in breast cancer (review) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kishimoto T, Akira S, Narazaki M, Taga T. Interleukin-6 family of cytokines and gp130. Blood. 1995;86:1243–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xing Z, Gauldie J, Cox G, et al. IL-6 is an antiinflammatory cytokine required for controlling local or systemic acute inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:311–320. doi: 10.1172/JCI1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chomarat P, Banchereau J, Davoust J, Palucka AK. IL-6 switches the differentiation of monocytes from dendritic cells to macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:510–514. doi: 10.1038/82763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hegde S, Pahne J, Smola-Hess S. Novel immunosuppressive properties of interleukin-6 in dendritic cells: inhibition of NF-kappaB binding activity and CCR7 expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:1439–1441. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0969fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mege JL, Meghari S, Honstettre A, Capo C, Raoult D. The two faces of interleukin 10 in human infectious diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:557–569. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mosser DM, Zhang X. Interleukin-10: new perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:205–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonasio R, von Andrian UH. Generation, migration and function of circulating dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Park J, Foss D, Goldschneider I. Thymus-homing peripheral dendritic cells constitute two of the three major subsets of dendritic cells in the steady-state thymus. J Exp Med. 2009;206:607–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawabata Y, Hirokawa M, Komatsuda A, Sawada K. Clinical applications of CD34+ cell-selected peripheral blood stem cells. Ther Apher Dial. 2003;7:298–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]