Abstract

The p53 transcription factor regulates the expression of genes involved in cellular responses to stress, including cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. The p53 transcriptional program is extremely malleable, with target gene expression varying in a stress- and cell type-specific fashion. The molecular mechanisms underlying differential p53 target gene expression remain elusive. Here we provide evidence for gene-specific mechanisms affecting expression of three important p53 target genes. First we show that transcription of the apoptotic gene PUMA is regulated through intragenic chromatin boundaries, as revealed by distinct histone modification territories that correlate with binding of the insulator factors CTCF, Cohesins and USF1/2. Interestingly, this mode of regulation produces an evolutionary conserved long non-coding RNA of unknown function. Second, we demonstrate that the kinetics of transcriptional competence of the cell cycle arrest gene p21 and the apoptotic gene FAS are markedly different in vivo, as predicted by recent biochemical dissection of their core promoter elements in vitro. After a pulse of p53 activity in cells, assembly of the transcriptional apparatus on p21 is rapidly reversed, while FAS transcriptional activation is more sustained. Collectively these data add to a growing list of p53-autonomous mechanisms that impact differential regulation of p53 target genes.

Key words: transcription, PUMA, p21, FAS, CTCF, chromatin boundary, core promoter, non-coding RNA

Introduction

The importance of the p53 network in cancer biology is undisputed. TRP53 is the most commonly mutated tumor suppressor gene, with inactivating mutations occurring in about half of human cancers.1 Importantly, it is estimated that 11 million patients worldwide carry tumors with wild-type p53 that could be activated to induce tumor regression, thus making research into p53-based therapies a top priority in modern medicine.2 However, the development of these therapies is hampered by the fact that p53, which acts as a signaling node within a vast gene network, is a highly pleiotropic factor. Cells can adopt starkly different responses upon p53 activation, such as reversible cell cycle arrest versus apoptosis. The effects of this pleiotropy are manifested in the clinic, where activation of p53 by genotoxic stress leads to cancer cell death and tumor regression only in a fraction of cases.3–9 Conversely, systemic activation of p53 causes many of the undesirable side effects of genotoxic therapies by triggering apoptosis in healthy tissues.10 Therefore, understanding the mechanisms defining cell fate choice in response to p53 activation is a prerequisite for the design of therapeutic tools that selectively drive cancer cells into p53-dependent apoptosis while sparing normal tissues.

First and foremost, p53 is a transcription factor.11–13 Although some transcription-independent functions have been ascribed to this tumor suppressor,14–19 its role as a transcriptional regulator accounts for most of its biological activity.20–25 p53 induces cell cycle arrest via transcriptional activation of genes such as the CDK-inhibitor p21 (CDKN1A)26 and the inhibitor of the G2/M transition 14-3-3π (SFN).27 Conversely, p53-dependent apoptosis is mediated by transactivation of genes involved in the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (e.g., PUMA/BBC3, NOXA),28–30 and the extrinsic death receptor pathway (e.g., FAS, DR5).31,32 Much of the pleiotropy associated with p53 is due to the flexible nature of the p53 transcriptional program. Distinct subsets of p53 target genes are activated in different cell types and in response to diverse stimuli, which reveals the action of factors modulating p53 transactivation potential in a gene-specific manner.33–45 A major goal in the p53 field is to identify these gene-specific co-regulators and to elucidate how they work. Eventually, this knowledge will enable strategies to manipulate the activity of these factors toward more efficient p53-based therapies.

A prevalent hypothesis in the field is that cell fate choice is defined by selective binding of p53 to the response elements found at target genes. This “p53-centric” form of regulation could be achieved through p53 post-translational modifications and/or p53 interacting partners. For example, phosphorylation of Ser46 of p53 was shown to induce preferential binding and transactivation of p53AIP1, and purportedly increasing p53-dependent apoptosis.46 However recent studies demonstrated that over a panel of cell lines there is no correlation with Ser46 phosphorylation and the induction of apoptosis or the expression of p53AIP1.47 Furthermore, Nutlin-3, the small molecule inhibitor of MDM2, induces p53 activation without phosphorylation and stimulates apoptosis in some cell types.48,49 Similarly, interaction of p53 with the ASPP proteins has been suggested to lead to preferential binding of p53 to the apoptotic genes PIG3 and BAX but not to cell cycle arrest genes such as p21.50 Conversely, interaction of p53 with the HZF protein seems to facilitate p53 association with the cell cycle arrest genes p21 and SFN, while preventing interaction with the pro-apoptotic genes BAX and NOXA, thus promoting cell survival.51 While intriguing, these studies stand in contrast to several others that demonstrate that p53 binding to its cognate p53REs is invariant under a variety of stress stimuli. For example, under conditions of UV-irradiation and γ-irradiation, which lead to different p53 target gene expression patterns,33 p53 binding to its canonical targets p21, PUMA, BAX, p53AIP1 and PIG3 is indistinguishable.52 Furthermore, recent genome-wide studies of p53 chromatin binding demonstrated that under conditions where p53 promotes apoptosis, it binds nonetheless to target genes in multiple functional categories, rather than to a distinct apoptotic subset.53

As the hypothesis that differential p53 binding as a determinant of cell fate choice has come into question, it has become increasingly clear that the context in which p53 functions at its individual target genes is exceedingly important. Several “p53-autonomous” mechanisms could influence gene expression independently of p53 modification, p53-DNA association or p53 interacting partners. Recently several instances of these context-dependent regulatory mechanisms have been described. For example, the hCAS/CSE1L protein associates with a distinct subset of p53 target genes (PIG3, p53AIP1 and p53R2) and loss of hCAS/CSE1L results in an imbalance in the p53 transcriptional program leading to an attenuated apoptotic response.35 Importantly, hCAS does not affect p53 binding to DNA but rather acts by somehow reducing the levels of repressive histone marks at select p53 target loci. More recently, it was demonstrated that core promoter elements found at the p53 target genes p21, FAS and APAF1 determine the rate of transcriptional apparatus assembly and the duration of transcription re-initiation, all in a p53-independent manner.54 The p21 promoter harbors elements that facilitate rapid but brief rounds of transcription, while elements found in FAS and APAF1 promoters dictate slow but sustained rounds of transcription.54 Collectively these results suggest that p53 target genes exist within unique regulatory landscapes, as defined by chromatin environments and promoter sequences, which play a significant and previously underappreciated role in determining eventual gene expression in response to stress. Here we provide further evidence for the existence of p53-autonomous mechanisms that impact differential regulation of p53 target genes. We first expand upon our recent findings that expression of the apoptotic gene PUMA is regulated by non-canonical intragenic chromatin boundaries.55 We then shift gears and provide in vivo evidence confirming the finding that “hard-wired” core promoter elements regulate the kinetics of p53 target gene expression.

Results

The PUMA locus displays a curious chromatin landscape that reveals an unusual mode of regulation.

PUMA is a BH3-only domain protein that antagonizes the function of pro-survival members of the Bcl-2 family and facilitates BAX translocation to the mitochondria.56,57 PUMA is a direct transcriptional target of p53 and a key mediator of p53-induced apoptosis.15,21,28,29 The PUMA gene is comprised of an ∼12 kb locus, which harbors two alternative promoters, with two adjacent p53REs residing just upstream of Exon 1a (Fig. 1A).

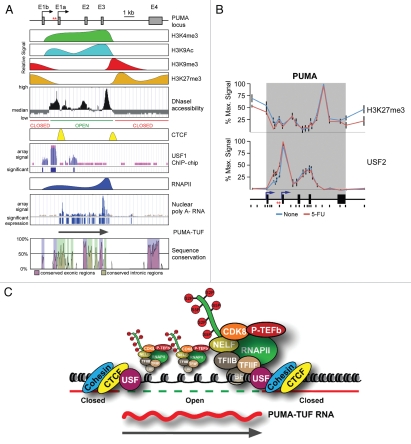

Figure 1.

Non-canonical transcriptional regulation at the PUMA locus. (A) A linear scale model of the PUMA locus indicating the exon structure and dual transcription start sites followed by a schematic summary of ChIP data, DNase I accessibility data and RNA analysis. Primary ChIP data for H3K4me3, H3K9Ac, H3K9me3, CTCF and RNAPII was previously published in Gomes and Espinosa.55 Primary data for H3K27me3 and USF2 is shown in (B). Data on DNaseI accessibility, USF1 occupancy and poly A- nuclear RNA was obtained from the USCS genome browser after analysis of publicly available genome wide datasets.62,66,67 Several lines of experimental evidence supporting the existence of PUMA-TUF were published in Gomes and Espinosa.55 PUMA locus conservation plot is an adapted view of VI STA plot data (http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml) comparing human and murine genomic sequences. (B) ChIP assays were performed with whole-cell extracts from control and 5-FU-treated (8 h) HCT116 p53+/+ cells with antibodies recognizing H3K27me3 and USF2. The locus maps are a condensed scale model of those seen in (A). The location of 20 Real-Time PCR amplicons used in ChIP assays is also shown; red asterisks represent the p53RE s. The gray band represents the annotated transcribed region. (C) A model summarizing the transcriptional state of the PUMA locus prior to p53 activation.

Recently we demonstrated that PUMA transcription is regulated by non-canonical mechanisms involving intragenic chromatin boundaries.55 The first half (∼6 kb) of the PUMA locus constitutively harbors histone marks of transcriptional activation. For example, histone H3 tri-methylation of lysine 4 (H3K4me3), which is typically observed ∼500 bp downstream of poised and active promoters,58 is found throughout the first 6 kb of the PUMA locus, with consistent levels detectable from Exon 1b until a precipitous drop off after Exon 3 (Fig. 1A). An additional mark of activation, histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9Ac), normally associates with enhancers and core promoters of transcriptionally active genes.59 On the PUMA locus H3K9Ac is again constitutively found throughout the first half of gene, with major peaks around the promoters and Exon 3 (Fig. 1A). Interestingly these histone marks of active transcription are flanked by histone marks associated with transcriptional silencing. Histone H3 lysine 9 tri-methylation (H3K9me3) is typically associated with a repressed transcriptional state and the presence of heterochromatin.60 We observed the clear presence of H3K9me3 upstream of the transcriptional start sites, and interestingly just downstream of the precipitous drop in H3K9Ac levels within intron 3 (Fig. 1A). Tri-methylation of histone 3 Lysine 27 (H3K27me3) is another mark of associated with transcriptional silencing.61 On PUMA H3K27me3 is found upstream of the transcriptional start sites and again interestingly just downstream of Exon 3, following the precipitous drop in H3K4me3 and H3K9Ac levels (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, H3K27me3 levels do not change following transcriptional activation upon p53 activation by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (Fig. 1B). Collectively these data suggest that the PUMA locus harbors an unusual chromatin environment, with the first 6 kb being defined by marks of active transcription and an ‘open’ chromatin state, while the flanking regions being defined by marks of transcriptional repression and a ‘closed’ chromatin state. This model is clearly supported by DNaseI accessibility assays, which show a long stretch of ‘open’ chromatin starting upstream of Exon 1a and extending downstream of Exon 3 (Fig. 1A).62 What factors might be mediating this unusual intragenic chromatin domain?

The CTCF zinc finger protein is involved in definition of chromatin boundaries, enhancer blocking and formation of chromatin loops.63,64 We observed that CTCF occupies two intragenic sites within PUMA, one around the core promoters and a second site just downstream of Exon 3, both of which overlap with the boundaries of the ‘open’ and ‘closed’ chromatin domains (Fig. 1A). We further demonstrated that CTCF knockdown leads to loss of H3K9me3 within PUMA and elevated basal PUMA mRNA expression.55 Collectively these data suggest that CTCF helps initiate/maintain the chromatin boundaries within PUMA and functions to repress the basal transcription of this potent apoptotic gene. However, as several chromatin signatures were still preserved upon CTCF knockdown,55 we hypothesized that additional factors must play a role in maintaining the observed chromatin boundaries. Accordingly, we observed that USF2 is constitutively associated within the PUMA locus in a manner overlapping with the previously defined chromatin boundaries (Fig. 1B). In addition to being associated with direct transcriptional activation, the USF factors have also been demonstrated to function as chromatin boundary elements that prevent the spreading of heterochromatin at β-globin genes.65 It is therefore possible that USF factors are also responsible for initiating/maintaining the peculiar intragenic chromatin architecture observed on PUMA. Of note, genome-wide studies of USF1 occupancy detected binding around the upstream boundary within PUMA (Fig. 1A).66

What is the consequence of this unusual chromatin architecture on the transcriptional competence of PUMA? Correlating with the ‘open’ nature of the first half of PUMA and the association of histone marks indicative of active transcription, we demonstrated that RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) is also constitutively associated with this region (Fig. 1A).55 Along with RNAPII a variety of general transcription factors (GTFs) (including TBP, TFIIB and TFIIF), Mediator (CDK8) and elongation factors (P-TEFb) are also constitutively associated with the first half of PUMA.55 We further demonstrated that these transcriptional complexes are active and give rise to a large sense-strand RNA of unknown coding capacity representing regions of the PUMA locus starting close to Exon 1a and terminating 100–200 bp after the end of Exon 3.55 We have dubbed this transcript PUMA-TUF, for PUMA transcript of unknown function (Fig. 1A). Genome-wide studies of nuclear, non-polyadenylated RNAs supports our observations that the first half of PUMA is constitutively transcribed (Fig. 1A).67 Interestingly this portion of the PUMA locus shows unusually high sequence conservation within intronic regions (Fig. 1A), which raises the intriguing possibility that PUMA-TUF may have a conserved cellular function and not simply be a consequence of promiscuous transcription from ‘open’ chromatin.

Do CTCF and cohesin complexes induce gene looping at the PUMA locus?

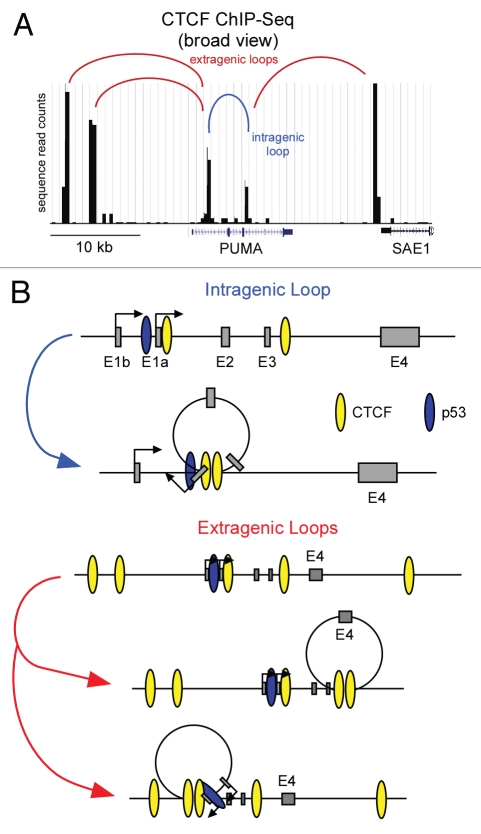

In addition to CTCF and USF1-2, we observed that the CTCF-associated Cohesins SMC1 and Rad21 also associate with the boundaries in the PUMA intragenic region.55 Genome-wide studies revealed that most CTCF binding sites occur within intergenic regions of the genome,64 which agrees with CTCF's described roles in enhancer blocking and the prevention of heterochromatin spreading into actively transcribed genes.68 It has been proposed that these CTCF functions involve the formation of ‘chromatin loops’, in which two distant sites of CTCF binding are brought into close proximity in the three-dimensional milieu of the nucleus.69 These loops, which can be detected by 3C technology, may be facilitated by Cohesins and seem to be regulated in a cell type- and signaling-specific manner.69 These observations create the intriguing possibility that the sites of CTCF-Cohesin binding within PUMA could mediate the formation of chromatin loops (Fig. 2). One possibility is that the dual sites of intragenic CTCF-Cohesin occupancy create an intragenic loop (Fig. 2B). Such a hypothesis fits well with our current understanding of the transcriptional regulation of PUMA. Recall that the first half of PUMA is constitutively transcribed and harbors an ‘open’ chromatin state. This intragenic region could be kept in isolation from the rest of the gene via an intragenic loop, and p53 activation could ‘break’ this loop, allowing for RNAPII travel into the 3′ end of the gene, with ensuing expression of PUMA mRNA (Fig. 2B). Consequently, by reducing the cellular pools of CTCF we might be undoing chromosomal loops, which then allows for more RNAPII to travel into the 3′ end of PUMA. Alternatively, these CTCF-Cohesin complexes could be forming ‘extragenic loops’ with CTCF binding sites flanking the PUMA locus observed in genome-wide studies (Fig. 2A).64 These extragenic interactions could bring important regulatory elements to the PUMA proximal promoters to allow proper regulation of the locus. The possibility that gene looping may be occurring on the PUMA locus is highly interesting and 3C studies are underway to determine if any loops exist and if they have a functional consequence on the expression of PUMA.

Figure 2.

Models of potential CTCF-induced gene looping on the PUMA locus. (A) An adapted UCSC genome browser view of PUMA and surrounding genomic sequence displaying CTCF binding data from CD4+ T cells80 denoting potential CTCF looping sites. (B) A general schematic of potential PUMA locus intragenic and extragenic CTCF-mediated loops.

p53-dependent transcriptional activation of p21 is rapidly reversed in vivo.

Recent biochemical analyses by the Emerson lab revealed an important role for core promoter elements in differential regulation of p53 target genes.54 The core promoter of a gene is defined as the minimal DNA sequence required for accurate RNAPII recruitment and transcription initiation, and can be comprised of a myriad of core promoter elements (CPEs) including the TATA box, the Downstream core Promoter Elements (DPE), GC-rich islands and Initiator motifs (Inr).70 These CPEs are responsible for the recruitment of GTFs to the core promoter, which in turn are responsible for the recruitment of RNAPII and formation of the pre-initiation complex (PIC). Additionally, CPEs can determine the sensitivity of a given promoter to distal enhancer elements, thus providing specificity in response to activator-induced gene expression.71 Core promoters found at p53 target genes harbor a diverse collection of CPEs, but it is unclear how these different architectures may influence their mode of expression in response to stress.72

Using elegant in vitro transcription assays, Morachis et al.54 showed that the CPEs found at the p21 and FAS promoters determine both the kinetics of PIC assembly and the re-initiation capacity of the transcriptional apparatus.54 They observed that the p21 promoter undergoes rapid PIC assembly and transcription initiation, but re-initiates poorly, thus being transcriptionally competent for a short period of time. In contrast, the FAS promoter undergoes slow PIC formation and transcriptional initiation, but was competent for numerous rounds of effective re-initiation. Importantly, the assays employed did not include p53REs or p53 protein. These data suggest that, at least in vitro, the core promoter architecture of p53 target genes can influence their expression kinetics independently of p53. A key prediction of these studies is that after a pulse of p53 activity in cells, different p53 target genes will not only engage in productive transcription at different velocities, but would also be inactivated with different kinetics. Early microarray experiments documented extensively the differential kinetics of p53 target gene activation, with p21 being classified as an early response gene.33 However, the kinetics of p53 target gene inactivation has not been analyzed. To investigate this issue we took advantage of the small molecule activator of p53, Nutlin-3. Nutlin-3 binds to and antagonizes the function of the p53 repressor MDM2, leading to activation of p53 in the absence of DNA damage, and importantly its effects are completely reversible upon removal from cell culture.49 Treatment of HCT116 cells with Nutlin-3 for 8 h leads to the accumulation of cellular p53 (Fig. 3B) and induces the transcriptional activation of p53 target genes, including p21 and FAS.49,73,74 Following removal of Nutlin-3 from cell cultures, p53 levels are drastically reduced within 30 min and drop below basal levels after 60 min (Fig. 3B). If the in vitro observation that p21 is rapidly activated and shut off, while FAS is slowly activated but sustained, this should be reflected in the reversal of the transcriptional events taking place at these individual loci. We began to test this prediction by performing first a detailed ChIP analysis of the p21 locus post-Nutlin-3 removal (Fig. 3C).

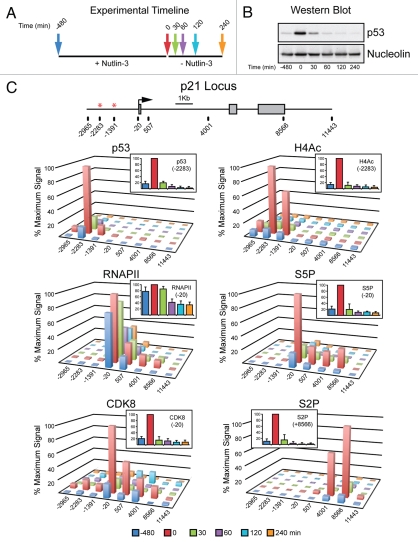

Figure 3.

Rapid inactivation of p21 transcription following transient p53 activation in cells. (A) Experimental timeline. HCT116 cells were treated with Nutlin-3 for 8 h, drug was washed out and cell extracts were harvested at 0, 30, 60, 120 and 240 min following Nutlin-3 removal. (B) Western blot analysis demonstrating p53 accumulation in response to Nutlin-3 treatment and rapid degradation following drug removal. Nucleolin serves as a loading control. (C) A linear scale model of the p21 locus indicating exon structure, transcription start site and red asterisks representing the p53REs. The location of 8 PCR amplicons used in ChIP assays is also shown. ChIP assays were performed with antibodies recognizing total p53, H4Ac, CDK8, total RNAPII , S5P-CTD and S2P-CTD.

We have previously demonstrated that activation of the p21 locus correlates with p53-dependent increases in histone acetylation, recruitment of the Mediator complex and conversion of paused RNAPII into an elongation competent form.40,42,43 Following 8 h of Nutlin treatment, a clear increase in chromatin-bound p53 is observed at the p53REs on the p21 locus along with enhanced histone acetylation (H4Ac) (Fig. 3C). The CDK8 subunit of the Mediator complex is also recruited to the p21 promoter, consistent with its demonstrated role as a positive-regulator of transcription on select p53 target genes.40 Following Nutlin-3 treatment, transcriptional activation is evidenced by increased levels of RNAPII within the body of the gene (Fig. 3C). It is widely accepted that phosphorylation of the heptad repeats (amino acid sequence YSPTSPS) in the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of RNAPII is indicative of transcriptional state. Whereas phosphorylation of serine 5 (S5P-CTD) is associated with promoter escape, serine 2 phosphorylation (S2P-CTD) accumulates towards the 3′ end of genes and is indicative of effective elongation.75 Accordingly, levels of both S5P-CTD and S2P-CTD increase drastically at the p21 locus upon Nutlin-3 treatment with their characteristic 5′ and 3′ polarities, respectively (Fig. 3C).

Surprisingly, all marks of transcriptional activation at the p21 locus are reduced to near or below basal levels after only 30 min of Nutlin-3 removal (Fig. 3C). The dramatic loss of p53 is perhaps not too surprising as MDM2 inhibition is immediately relieved after Nutlin-3 removal. However, the rapid loss of H4Ac suggests that histone deacetylases (HDACs) may be constitutively associated with the p21 locus and that, while their function is overcome during transcriptional activation, they quickly reverse the hyperacetylated state induced by p53.76,77 The rapid, concomitant loss of CDK8 and active RNAPII from the gene is indicative of an immediate disruption of the enhancer-promoter dialog that leads to stimulation of RNAPII elongation. How is this rapid inactivation achieved? A simple hypothesis is that the Mediator complex, which is recruited directly by p53, arbitrates this communication, and that as soon as the levels of chromatin-bound p53 are reduced, so is Mediator association and stimulation of RNAPII activity at post-recruitment steps. While the reductions in S5P-CTD and S2P-CTD levels correlate with reduced RNAPII levels, it is also possible that CTD phosphatases function on this locus to facilitate immediate transcriptional silencing upon loss of the activator.78,79 Taken together these data provide strong evidence that some p53 target genes, such as p21, can be rapidly silenced upon reversal of p53 activation, which could be dictated by a core promoter architecture that is non-permissive to sustained transcriptional re-initiation, as first evidenced by the in vitro transcription assays performed by Morachis et al.54

p21 and FAS display different kinetics of transcriptional inactivation after a pulse of p53 activity in cells.

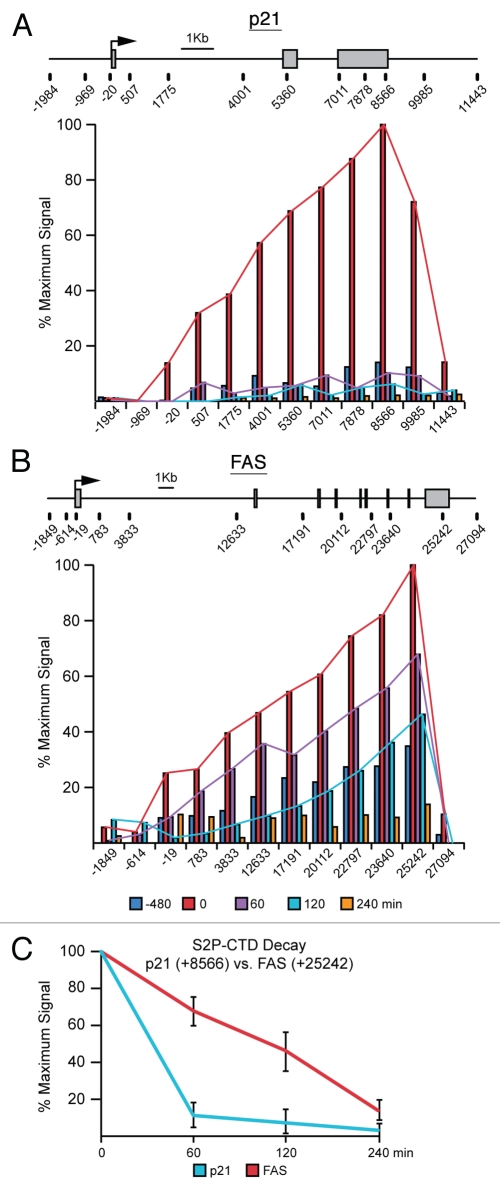

Next, we employed ChIP assays with antibodies recognizing actively elongating RNAPII (S2P-CTD) to compare the timing of transcriptional silencing of p21 versus FAS. As expected, after 8 h of Nutlin-3 treatment S2P-CTD levels are dramatically increased over basal and progressively increase towards the 3′ end at both the p21 and FAS loci (Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly, the decay in S2P-CTD signal is much slower on the FAS locus, only falling below basal levels 240 min after removal of the drug (Fig. 4). Focusing in on the 3′ end of each of these genes following Nutlin-3 removal demonstrates an immediate drop of S2P-CTD levels on p21, whereas elongating RNAPII persists for a longer time on FAS (Fig. 4C). Collectively these data demonstrate that the p21 and FAS loci clearly have different kinetics of inactivation, with p21 being quickly silenced following loss of active p53 while FAS inactivation is clearly delayed. Furthermore these data correlate well with in vitro observations for these loci and suggest that the core promoter architecture of p53 target genes plays an important role in determining their eventual pattern of expression.

Figure 4.

FAS displays extended transcriptional competence after p53 shut down. (A and B) Linear scale models of the p21 and FAS loci indicating exon structures and transcription start sites. The location of 12 PCR amplicons used in ChIP assays for each locus is also shown. ChIP assays were performed with antibodies recognizing S2P-CTD. (C) Summary of ChIP data from the 3′ end of p21 (+8,566) and FAS (+25,242) over the time course following Nutlin-3 treatment and removal.

Materials and Methods

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays.

All ChIP assays were performed as finely detailed in Gomes et al. 2006.42 Briefly for PUMA ChIPs, subconfluent HCT116 cultures were treated with 5-FU (375 µM) for 8 h, fixed with 1% formaldehyde and then whole-cell lysates were prepared. Protein lysates (1 mg) were subject to ChIP with the indicated antibodies, followed by DNA purification and Q-PCR with the indicated primer sets, detailed in Gomes and Espinosa 2010.55 For Nutlin reversal experiments, HCT116 cells were treated with Nutlin-3 (10 µM) for 8 h, cells were washed twice with 1X PBS, replaced with Nutlin-free media and harvested at 0, 30, 60, 120 and 240 minute intervals. Primers for FAS are detailed in Supplemental Table 1.

Protein immunoblot analysis.

10 µg of total protein extract harvested as described above were loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blots were probed with primary antibodies: p53 (DO-1, Oncogene) and nucleolin (sc-8031, Santa Cruz), developed with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz) and ECL detection reagents (GE Healthcare).

Concluding Remarks

Here we have described two gene-specific mechanisms that mediate p53 target gene expression in a manner independent of p53 function. First, we demonstrated that unique intragenic chromatin domain environments ultimately determine functional expression from the apoptotic PUMA gene locus. Second, we provided in vivo data supporting the in vitro results indicating that the core promoter architecture of p53 target genes determine the duration of p21 and FAS transcriptional competence after RNAPII initiation.

These observations raise several intriguing possibilities in regards to the regulation of p53 target gene expression in response to cellular stress. First, functional PUMA mRNA expression may be achieved in the absence of stress and p53 activation simply by modulating the chromatin architecture of the locus, perhaps via modulation of chromatin boundary factors such as CTCF, Cohesins and USF1-2. Can this endogenous mechanism be exploited to facilitate preferential expression of apoptotic PUMA in the treatment of cancer? Second, the identification of PUMA-TUF, which appears to be highly conserved, suggests this RNA may have a cellular function. Is that function involved in the regulation of PUMA expression or other cellular processes? Third, select groups of p53 target genes (e.g. cell cycle arrest vs. apoptosis) seem to harbor CPEs dictating rapid but brief as opposed to slow but sustained rounds of transcription. Can these intrinsic characteristics be exploited to facilitate the sustained expression of apoptotic genes upon therapeutic activation of p53?

Collectively these findings provide important evidence that differential gene expression following p53 activation, and ultimately cell fate choice in response to cellular stress, cannot simply be defined as a consequence of differential p53 binding to DNA. Rather, the individual ‘personalities’ of each p53-target gene are likely to strongly influence their ultimate expression pattern. The illumination and deciphering of these mechanisms brings us closer to the ultimate goal of developing targeted therapies allowing for the tipping of the cell fate choice balance, thereby forcing cancer cells into apoptosis in response to p53 activation.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Stephanie Szostek for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1-CA117907. J.M.E. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist. N.P.G. was supported in part by NIH training grant T32GM07135.

Abbreviations

- 3C

chromosome conformation capture

- CDK8

cyclin dependent kinase 8

- CTCF

zinc finger CCCTC-binding factor

- CPE

core promoter element

- GTF

general transcription factor

- HZF

hematopoietic zinc-finger

- MDM2

human homolog of murine double minute 2

- p53AIP1

p53-regulated apoptosis-inducing protein

- p53REs

p53 response elements

- PIG3

p53 inducible gene 3

- PUMA

p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis

- P-TEFb

positive transcription elongation factor b

- PUMA-TUF

PUMA transcript of unknown function

- Q-PCR

quantitative PCR

- RNAPII

RNA polymerase II

- S5P and S2P-CTD

serine 5 and 2 phosphorylation of the RNAPII C-terminal domain

- TBP

TATA-binding protein

- TFIIB and F

transcription factor II B and F

- USF

upstream transcription factor

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/12998

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Soussi T, Kato S, Levy PP, Ishioka C. Reassessment of the TP53 mutation database in human disease by data mining with a library of TP53 missense mutations. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:6–17. doi: 10.1002/humu.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown CJ, Lain S, Verma CS, Fersht AR, Lane DP. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the p53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:862–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saitoh S, Cunningham J, De Vries EM, McGovern RM, Schroeder JJ, Hartmann A, et al. p53 gene mutations in breast cancers in midwestern US women: null as well as missense-type mutations are associated with poor prognosis. Oncogene. 1994;9:2869–2875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Vargas H, Ballestar E, Carmona-Saez P, von Kobbe C, Banon-Rodriguez I, Esteller M, et al. Transcriptional profiling of MCF7 breast cancer cells in response to 5-Fluorouracil: relationship with cell cycle changes and apoptosis and identification of novel targets of p53. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1164–1175. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viktorsson K, De Petris L, Lewensohn R. The role of p53 in treatment responses of lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:868–880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troester MA, Hoadley KA, Sorlie T, Herbert BS, Borresen-Dale AL, Lonning PE, et al. Cell-type-specific responses to chemotherapeutics in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4218–4226. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisold S, Linnebacher M, Ryschich E, Antolovic D, Hinz U, Klar E, et al. The effect of adenovirus expressing wild-type p53 on 5-fluorouracil chemosensitivity is related to p53 status in pancreatic cancer cell lines. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3583–3589. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i24.3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunz F, Hwang PM, Torrance C, Waldman T, Zhang Y, Dillehay L, et al. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:263–269. doi: 10.1172/JCI6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe SW, Bodis S, McClatchey A, Remington L, Ruley HE, Fisher DE, et al. p53 status and the efficacy of cancer therapy in vivo. Science. 1994;266:807–810. doi: 10.1126/science.7973635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botchkarev VA, Komarova EA, Siebenhaar F, Botchkareva NV, Komarov PG, Maurer M, et al. p53 is essential for chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5002–5006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farmer G, Bargonetti J, Zhu H, Friedman P, Prywes R, Prives C. Wild-type p53 activates transcription in vitro. Nature. 1992;358:83–86. doi: 10.1038/358083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zambetti GP, Bargonetti J, Walker K, Prives C, Levine AJ. Wild-type p53 mediates positive regulation of gene expression through a specific DNA sequence element. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1143–1152. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, et al. Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein. Science. 1991;252:1708–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.2047879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caelles C, Helmberg A, Karin M. p53-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcriptional activation of p53-target genes. Nature. 1994;370:220–223. doi: 10.1038/370220a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science. 2005;309:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.1114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Droin NM, Newmeyer DD, Schuler M, et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erster S, Moll UM. Stress-induced p53 runs a direct mitochondrial death program: Its role in physiologic and pathophysiologic stress responses in vivo. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1492–1495. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.12.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erster S, Mihara M, Kim RH, Petrenko O, Moll UM. In vivo mitochondrial p53 translocation triggers a rapid first wave of cell death in response to DNA damage that can precede p53 target gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6728–6741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6728-6741.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, et al. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Somasundaram K, El-Deiry WS. Inhibition of p53-mediated transactivation and cell cycle arrest by E1A through its p300/CBP-interacting region. Oncogene. 1997;14:1047–1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhang L. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627984100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwakuma T, Lozano G. Crippling p53 activities via knock-in mutations in mouse models. Oncogene. 2007;26:2177–2184. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chao C, Saito S, Kang J, Anderson CW, Appella E, Xu Y. p53 transcriptional activity is essential for p53-dependent apoptosis following DNA damage. EMBO J. 2000;19:4967–4975. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.18.4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimenez GS, Nister M, Stommel JM, Beeche M, Barcarse EA, Zhang XQ, et al. A transactivation-deficient mouse model provides insights into Trp53 regulation and function. Nat Genet. 2000;26:37–43. doi: 10.1038/79152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig RL, Bates S, Vousden KH. Differential activation of target cellular promoters by p53 mutants with impaired apoptotic function. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4952–4960. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, He TC, Zhang L, Thiagalingam S, et al. 14-3-3 sigma is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7:683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, Nemoto J, Shibue T, Yamashita T, et al. Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science. 2000;288:1053–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller M, Wilder S, Bannasch D, Israeli D, Lehlbach K, Li-Weber M, et al. p53 activates the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) gene in response to DNA damage by anticancer drugs. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2033–2045. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takimoto R, El-Deiry WS. Wild-type p53 transactivates the KILLER/DR5 gene through an intronic sequence-specific DNA-binding site. Oncogene. 2000;19:1735–1743. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao R, Gish K, Murphy M, Yin Y, Notterman D, Hoffman WH, et al. Analysis of p53-regulated gene expression patterns using oligonucleotide arrays. Genes Dev. 2000;14:981–993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattia M, Gottifredi V, McKinney K, Prives C. p53-Dependent p21 mRNA elongation is impaired when DNA replication is stalled. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1309–1320. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01520-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka T, Ohkubo S, Tatsuno I, Prives C. hCAS/CSE1L associates with chromatin and regulates expression of select p53 target genes. Cell. 2007;130:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohkubo S, Tanaka T, Taya Y, Kitazato K, Prives C. Excess HDM2 impacts cell cycle and apoptosis and has a selective effect on p53-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16943–16950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottifredi V, Shieh S, Taya Y, Prives C. p53 accumulates but is functionally impaired when DNA synthesis is blocked. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1036–1041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021282898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottifredi V, Shieh SY, Prives C. Regulation of p53 after different forms of stress and at different cell cycle stages. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000;65:483–488. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedlander P, Haupt Y, Prives C, Oren M. A mutant p53 that discriminates between p53-responsive genes cannot induce apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4961–4971. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donner AJ, Szostek S, Hoover JM, Espinosa JM. CDK8 Is a Stimulus-Specific Positive Coregulator of p53 Target Genes. Mol Cell. 2007;27:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donner AJ, Hoover JM, Szostek SA, Espinosa JM. Stimulus-specific transcriptional regulation within the p53 network. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2594–2598. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.21.4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomes NP, Bjerke G, Llorente B, Szostek SA, Emerson BM, Espinosa JM. Gene-specific requirement for P-TEFb activity and RNA polymerase II phosphorylation within the p53 transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 2006;20:601–612. doi: 10.1101/gad.1398206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Espinosa JM, Verdun RE, Emerson BM. p53 functions through stress- and promoter-specific recruitment of transcription initiation components before and after DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1015–1027. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fei P, Bernhard EJ, El-Deiry WS. Tissue-specific induction of p53 targets in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7316–7327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouvard V, Zaitchouk T, Vacher M, Duthu A, Canivet M, Choisy-Rossi C, et al. Tissue and cell-specific expression of the p53-target genes: bax, fas, mdm2 and waf1/p21, before and following ionising irradiation in mice. Oncogene. 2000;19:649–660. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oda K, Arakawa H, Tanaka T, Matsuda K, Tanikawa C, Mori T, et al. p53AIP1, a potential mediator of p53-dependent apoptosis and its regulation by Ser-46-phosphorylated p53. Cell. 2000;102:849–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurihara A, Nagoshi H, Yabuki M, Okuyama R, Obinata M, Ikawa S. Ser46 phosphorylation of p53 is not always sufficient to induce apoptosis: multiple mechanisms of regulation of p53-dependent apoptosis. Genes Cells. 2007;12:853–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson T, Tovar C, Yang H, Carvajal D, Vu BT, Xu Q, et al. Phosphorylation of p53 on key serines is dispensable for transcriptional activation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53015–53022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D, Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuels-Lev Y, O'Connor DJ, Bergamaschi D, Trigiante G, Hsieh JK, Zhong S, et al. ASPP proteins specifically stimulate the apoptotic function of p53. Mol Cell. 2001;8:781–794. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Das S, Raj L, Zhao B, Kimura Y, Bernstein A, Aaronson SA, et al. Hzf Determines cell survival upon genotoxic stress by modulating p53 transactivation. Cell. 2007;130:624–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaeser MD, Iggo RD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis fails to support the latency model for regulation of p53 DNA binding activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:95–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012283399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei CL, Wu Q, Vega VB, Chiu KP, Ng P, Zhang T, et al. A global map of p53 transcription-factor binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2006;124:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morachis JM, Murawsky CM, Emerson BM. Regulation of the p53 transcriptional response by structurally diverse core promoters. Genes Dev. 2010;24:135–147. doi: 10.1101/gad.1856710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gomes NP, Espinosa JM. Gene-specific repression of the p53 target gene PUMA via intragenic CTCF-Cohesin binding. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1022–1034. doi: 10.1101/gad.1881010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yee KS, Vousden KH. Contribution of membrane localization to the apoptotic activity of PUMA. Apoptosis. 2008;13:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Xing D, Liu L. PUMA promotes Bax translocation by both directly interacting with Bax and by competitive binding to Bcl-XL during UV-induced apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3077–3087. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-11-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agalioti T, Chen G, Thanos D. Deciphering the transcriptional histone acetylation code for a human gene. Cell. 2002;111:381–392. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stewart MD, Li J, Wong J. Relationship between histone H3 lysine 9 methylation, transcription repression and heterochromatin protein 1 recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2525–2538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2525-2538.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1123–1136. doi: 10.1101/gad.381706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, et al. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell. 2008;132:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cuddapah S, Jothi R, Schones DE, Roh TY, Cui K, Zhao K. Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res. 2009;19:24–32. doi: 10.1101/gr.082800.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim TH, Abdullaev ZK, Smith AD, Ching KA, Loukinov DI, Green RD, et al. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2007;128:1231–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.West AG, Huang S, Gaszner M, Litt MD, Felsenfeld G. Recruitment of histone modifications by USF proteins at a vertebrate barrier element. Mol Cell. 2004;16:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rada-Iglesias A, Ameur A, Kapranov P, Enroth S, Komorowski J, Gingeras TR, et al. Whole-genome maps of USF1 and USF2 binding and histone H3 acetylation reveal new aspects of promoter structure and candidate genes for common human disorders. Genome Res. 2008;18:380–392. doi: 10.1101/gr.6880908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng J, Kapranov P, Drenkow J, Dike S, Brubaker S, Patel S, et al. Transcriptional maps of 10 human chromosomes at 5-nucleotide resolution. Science. 2005;308:1149–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1108625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips JE, Corces VG. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hou C, Dale R, Dean A. Cell type specificity of chromatin organization mediated by CTCF and cohesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3651–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Juven-Gershon T, Hsu JY, Theisen JW, Kadonaga JT. The RNA polymerase II core promoter—the gateway to transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Butler JE, Kadonaga JT. Enhancer-promoter specificity mediated by DPE or TATA core promoter motifs. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2515–2519. doi: 10.1101/gad.924301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gomes NP, Espinosa JM. Differential regulation of p53 target genes: it's (core promoter) elementary. Genes Dev. 2010;24:111–114. doi: 10.1101/gad.1893610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tovar C, Rosinski J, Filipovic Z, Higgins B, Kolinsky K, Hilton H, et al. Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in cancer: implications for therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1888–1893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507493103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paris R, Henry RE, Stephens SJ, McBryde M, Espinosa JM. Multiple p53-independent gene silencing mechanisms define the cellular response to p53 activation. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2427–2433. doi: 10.4161/cc.6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Komarnitsky P, Cho EJ, Buratowski S. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2452–2460. doi: 10.1101/gad.824700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10014–10019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gui CY, Ngo L, Xu WS, Richon VM, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor activation of p21WAF1 involves changes in promoter-associated proteins, including HDAC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1241–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307708100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yeo M, Lin PS, Dahmus ME, Gill GN. A novel RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase that preferentially dephosphorylates serine 5. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26078–26085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mandal SS, Cho H, Kim S, Cabane K, Reinberg D. FCP1, a phosphatase specific for the heptapeptide repeat of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II, stimulates transcription elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7543–7552. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7543-7552.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.