Abstract

Type C fractures of the distal humerus are difficult to treat and typically require open anatomical reduction and internal fixation. Here we describe our experience treating patients with type C distal humerus fractures using a trans-olecranon approach with bilateral plate fixation. Fifty-six patients (30 males, 26 females; mean age 49.8 years) were treated over a period of six years. Thirteen fractures were open and 43 closed; all were caused by falls or traffic accidents. All operations were performed successfully with no intraoperative complications. Mean duration of follow-up was 30 months (range 6–70). Mean duration of fracture healing was 2.8 months (range 2–4). Forty-seven out of 56 patients (84%) suffered no postoperative complications. One patient exhibited symptoms of ulnar nerve injury following surgery (nine exhibited symptoms before and after surgery). Two patients had mild cubitus varus deformities, four delayed olecranon osteotomy site healing, and two heterotopic ossifications. In summary, complications were minimal and outcomes satisfactory in patients with type C distal humerus fractures who underwent bilateral plate fixation via a trans-olecranon approach.

Introduction

Type C distal humerus fractures are one of the most difficult fractures to treat [1, 2]. Although the incidence is very low, this type of fracture is often associated with neurovascular injuries [3, 4]. Furthermore, most manual methods of reduction are unsatisfactory for type C distal humerus fractures; hence, surgical treatment is preferred [5]. Open anatomical reduction followed by internal fixation with a reconstruction plate is the most common approach [6–8], while closed reduction and external fixation by means of a ring fixator has recently been reported to be effective in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone [9]. Distraction reduction with external fixation can be employed during the early stage of the injury in patients with serious fracture displacement compressing neurovascular structures and in those who have severe soft tissue swelling (internal fixation can be then performed when the swelling subsides) [10].

Type C distal humerus fractures are typically high-energy injuries. Hence, significant swelling is usually apparent in the affected limb as are fracture blisters [11]. As a result of this, surgery may have to be delayed from several days to two to three weeks until the swelling subsides. Any delay in surgical repair following injury can have a significant influence on prognosis. A second common concern with type C distal humerus fractures is difficulty in obtaining adequate surgical exposure. The surgical approach dictates whether the operation can be carried out smoothly. A third issue with type C distal humerus fractures pertains to the unique structure of the distal humerus which makes plate fixation difficult.

A number of different surgical approaches have been used to repair of type C distal humerus fractures. These include posterior using a triceps flap, triceps lateral, combined lateral and medial, and trans-olecranon [10, 12]. It is unclear which of these is optimal. Here we describe our experience over a period of six years treating patients with type C distal humerus fractures using a trans-olecranon approach and bilateral plate fixation.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between July 2000 and June 2006, 56 patients with type C distal humerus fractures were treated in our department; all underwent bilateral plate fixation. Inclusion criteria were open reduction and internal fixation of type C distal humerus fractures.

Surgical timing

All patients with open fractures underwent emergency surgery except in cases where other life threatening injuries (cerebral trauma, visceral injuries in the chest and abdomen, etc.) were apparent. In such cases, the life threatening injuries were treated first and fracture repair was performed when patients’ vital signs were stable. Surgery was performed after swelling subsided in patients with closed fractures.

Surgical procedure

The patient was placed in a supine position. A pneumatic tourniquet was applied after brachial plexus block anaesthesia. The upper limb was placed in front of the chest, with the shoulder and elbow in flexion. A midline posterior elbow incision was made. The ulnar nerve was protected after being carefully dissected from the cubital tunnel. Dissection was carried out along the triceps brachii muscle bilaterally to the proximal ulna, and osteotomy was performed 2.0 cm distal to the tip of the olecranon. The proximal part of olecranon and its attached triceps tendon were retracted proximally to expose the distal humerus. After exposure of the fracture site, the intercondylar fracture was first reduced and temporarily fixed using K-wire to restore the smoothness of articular surface and convert the type C fracture to a type A fracture. The type A fracture was reduced and fixed with bilateral plates to ensure the stability of the medial and lateral columns of the distal humerus. Bilateral plates (Trauson Medical Instrument Co., Ltd, Changzhou, P.R. China) were pre-bent according to the morphology of the distal humerus. Medial and lateral plates were placed on the medial and posterolateral sides of the humerus at 90º to one another. The olecranon was then reduced and fixed by K-wire and tension band wire, and subcutaneous anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve was performed. Functional exercise was initiated 48 to 72 hours after the completion of surgery. In the case of open fractures, antibiotics (1.5 g cefuroxime) were administered twice daily for three to five days.

Clinical observation and follow-up assessment

Six weeks after surgery, outpatient department follow-up took place every two to three weeks until fracture healing was apparent and thereafter every three to six months. Implanted plates, K-wires and tension band wiring were removed one to three years after fracture healing, with final follow-up taking place approximately one year later. Assessments were made to detect local tenderness and pain to vertical percussion and abnormal local movement. Anteroposterior and lateral X-rays were obtained to monitor fracture healing (the films were interpreted independently by two senior radiologists). Fracture healing was defined by the following: (1) no local tenderness or pain to vertical percussion, (2) no abnormal movement, (3) X-ray revealing continuous callus at the fracture site and no obvious fracture line, and (4) the upper limb could lift and hold a 1 kg object for one minute without deformation at the fracture site. After fracture healing, patients were followed-up every 12 weeks. Postoperative complications were noted.

Results

Among the patients, 30 were male and 26 female. The mean patient age was 49.8 years, ranging from 18 to 70 years. Twenty-five fractures were on the left side and 31 were on the right side. Thirteen fractures were open and 43 closed. Among these, six were Gustilo type I fractures and seven were Gustilo type II fractures. Forty-three were closed fractures. Fracture causes included falling injury (29 cases) and traffic accidents (27 cases). According to AO/ASIF classification, all cases were classified as C type. Eight cases were associated with fractures in other parts of the body, including three distal radial fractures, two rib fractures, one fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus, one lumbar vertebral body fracture, and one clavicle fracture. Ulnar nerve injury was evident in nine patients before surgery.

The mean duration between injury and surgery was nine days, ranging from 0 to 17 days. Among the 13 patients with open fractures, only two underwent emergency surgery. In these patients, emergency debridement and fracture fixation were performed. Surgery was delayed in the remainder while other life threatening injuries were treated. The mean duration of delay in patients with open fractures was 11 days, ranging from five to 17 days. The mean duration of delay in patients with closed fractures was nine days, ranging from three to 17 days.

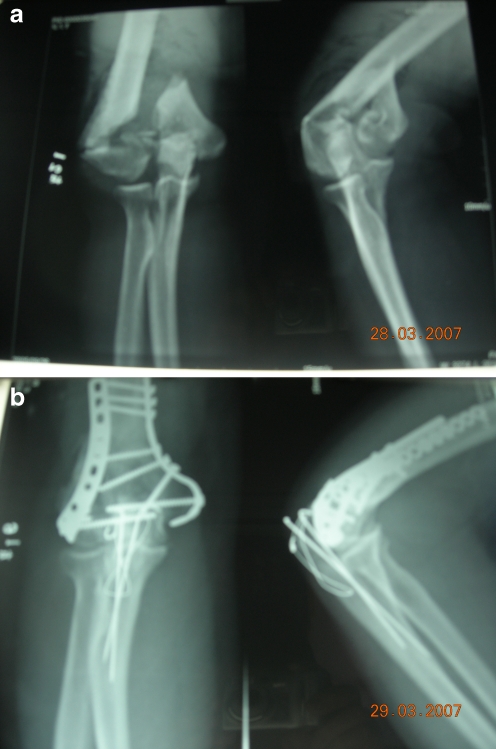

All operations were performed successfully with no intraoperative complications. A reconstructive plate (Trauson Medical Instrument Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China) was used in 21 cases and anatomical plate (Trauson Medical Instrument Co., Ltd.) in 35 cases (Fig. 1). External fixation was not performed in any case. Postoperative vacuum sealed drainage was used for patients with severe skin contusions.

Fig. 1.

Radiographs illustrating a representative type C distal humerus fracture. a Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral views. b Anteroposterior and lateral views following bilateral internal plate fixation via an olecranon osteotomy approach

The mean duration of follow-up was 30 months, ranging from six to 70 months. The mean duration of fracture healing was 2.8 months, ranging from two to four months. Forty-seven out of 56 patients (84%) suffered no postoperative complication.

Eleven out of 13 patients with open fractures had other injuries. These included other fractures (four patients) and ulnar nerve injury (seven patients; indicated by numbness or sensory loss in the ring and little fingers). Only four out of 43 patients with closed fractures had other fractures, while two had ulnar nerve injuries. Thus, a total of ten patients had symptoms of ulnar nerve injury; of these, symptoms were apparent before surgery in nine. After one to five months of treatment (oral Mecobalamin, 0.5 mg, three times/day), symptoms improved in six patients. Residual symptoms of ulnar nerve injury, including mild numbness in the ring and little finger were apparent in four patients. Of these, three exhibited mild hypothenar muscle atrophy with normal finger motor function (each of these patients had symptoms of ulnar nerve injury before surgery). Two patients had mild cubitus varus deformities, four had delayed healing at the olecranon osteotomy site, and two heterotopic ossifications. Table 1 summarises individual patient postoperative complications and the demographic and injury characteristics of these patients (details are shown in this table for the nine patients [16%] who had postoperative complications only).

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and injury characteristics and postoperative complications in the patients who experienced some form of postoperative complication

| Patient | Gender | Age (years) | Open/closed fracture | Gustilo type | AO/ASIF type | Other associated injuries | Days between injury and surgery | Postoperative complications and outcomes | Bone malunion | Follow-up duration (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Female | 70 | Open | II | C3 | Fracture of surgical neck of humerus, | 17 | Cubitus varus deformity | 68 | |

| 34 | Male | 59 | Open | I | C3 | Ulnar nerve injury | 14 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 5 months after the surgery | Heterotopic ossification | 31 |

| 49 | Male | 30 | Open | II | C2 | Ulnar nerve injury | 10 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 4 months after the surgery | Delayed healing at the site of olecranon osteotomy | 19 |

| 5 | Female | 27 | Open | I | C1 | Clavicle fracture, ulnar nerve injury | 0 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 3 months after the surgery | 50 | |

| 9 | Male | 65 | Closed | – | C2 | – | 3 | Delayed healing at the site of olecranon osteotomy | 53 | |

| 17 | Male | 59 | Closed | – | C2 | Ulnar nerve injury | 7 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 3 months after the surgery | 36 | |

| 23 | Female | 66 | Closed | – | C3 | – | 15 | Delayed healing at the site of olecranon osteotomy | 18 | |

| 55 | Male | 51 | Closed | – | C2 | – | 14 | Heterotopic ossification | 12 | |

| 12 | Male | 37 | Closed | – | C2 | – | 7 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 3 months after the surgery | 49 | |

| 24 | Female | 62 | Closed | – | C2 | – | 7 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 1 months after the surgery | 12 | |

| 53 | Male | 66 | Closed | – | C3 | – | 7 | Ring, little finger numbness, recovered 2 months after the surgery | 12 |

AO/ASIF Arbeitsgemeinschaft fuer Osteosynthesefragen/Association for the Study of Internal Fixation, HHS Harris hip score

Discussion

The optimal timing for initiating surgical repair of type C distal humerus fractures remains controversial [14, 15], with some surgeons advocating emergency surgery within 24 hours of injury [16]. In our experience, emergency surgery should be performed on patients with open fractures after thorough debridement. While in patients with closed fractures and severe initial local swelling, olecranon traction can be first applied and surgical fixation subsequently performed within one week after the swelling subsides. For patients with local blisters, blister extraction is necessary. Surgery should then be performed after the swelling subsides and the blister scab(s) falls off. This improves surgical safety and facilitates early post-surgery functional exercise.

Several commonly used approaches have been described for distal humerus fracture repair [2, 17, 18]. The posterior elbow approach using triceps flap involves obliquely cutting the triceps muscle to produce a flap. This approach can result in significant bleeding, muscle fibre breakdown, swelling, and fibrosis. Furthermore, a relatively long period of postoperative immobilisation is necessary, resulting in extensive adhesions and contracture between the triceps muscle and the distal humerus and surrounding peripheral tissue. Joint stiffness may be apparent and functional recovery of the joint impaired [19]. The triceps lateral approach is associated with less procedural injury and is relatively simple to perform. However, exposure of intercondylar area is relatively poor, fracture reduction can be difficult, and exploration of the ulnar nerve challenging [20]. A combined lateral and medial approach facilitates simple and extensive exposure of the operative field, does not affect the extension and flexion of the elbow, allows for simultaneous exploration and repair of the ulnar and radial nerves and is associated with less tissue injury. Exposure of the intercondylar area is relatively poor with this approach, however, and fracture reduction is difficult [21, 22]. The transolecranon approach has been used by many surgeons [5, 23]. This approach sufficiently exposes the articular surface of the distal humerus and negates the risk of triceps injury. Early post-surgical functional exercise can be instigated; however, interarticular fracture is a potential complication. The transolecranon approach was used in 56 cases of type C distal humerus fractures described herein. We found the operative field to be extensive, fracture reduction satisfactory and the implementation of early functional exercises easily possible.

Within the last seven years, a two-column theory of the distal humerus anatomy has been advocated whereby the coronal plane of the distal humerus is in the shape of a triangle, with the coronoid fossa and olecranon fossa accounting for the majority of the central area, and the medial and lateral condyles forming two strong columns by proximal extension [7, 24]. Fixation of the distal humerus must not only restore the capitellum-trochlea joint, but also the integrity of the medial and lateral columns. There are several options for fixation between the condyle and humeral metaphysis. These include the use of Y-shaped plates, single plates, double K-wire, and K-wire together with tension band wiring [10, 25]. The aim is to facilitate biomechanical reconstruction of the aforementioned two-column structure. Bilateral plate fixation was carried out in all 56 cases in our study. In each case, fracture reduction was satisfactory, fixation strong and durable, the fracture site stable and early post-surgical functional exercise possible.

Many complications have been reported following surgical repair of distal humerus fractures. These include infection, nerve injury, joint stiffness, heterotopic ossification, and delayed union or nonunion of the ulnar olecranon [5, 26, 27]. For instance, Kundel et al. reported that the incidences of heterotopic ossification and nerve injury were 49% and 33%, respectively, following open reduction and internal fixation [26]. In our study, ten out of 56 patients were found to have symptoms of ulnar nerve injury (among these patients, nine exhibited symptoms pre-surgery). This is well below the rate reported by Kundel et al. [26]. This may be due to intraoperative protection and anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. The incidence of heterotopic ossification in our study was also lower than that previously reported. Gofton et al. found that 13% of patients with type C distal humerus fractures exhibited postoperative heterotopic ossification [27]. The lower incidence in our study may relate to complete intraoperative haemostasis, unobstructed postoperative drainage, and early postoperative functional exercise. In contrast to findings of distal humeral nonunion from several previous reports [28–30], no instances of fixation failure were detected in this study. Presumably this was a reflection of strong bilateral plate fixation and satisfactory fracture reduction. Delayed healing at the olecranon osteotomy site was apparent in four patients. This may have been due to the early post-operative implementation of exercises. Healing ensued in all of these patients following decreases in the level of exercise intensity.

In summary, we found that use of a trans-olecranon approach and bilateral internal plate fixation was efficacious for the treatment of type C distal humerus fractures. Complications were minimal and healing satisfactory. We advocate the use of this approach for repair of type C distal humerus fractures.

Contributor Information

Zhen-hua Li, Phone: +86-021-66307304, FAX: +86-021-66301114, Email: 1966lzh@sina.com.

Zheng-dong Cai, Phone: +86-021-66307304, FAX: +86-021-66301114, Email: czd856@vip.sohu.com.

References

- 1.O’Driscoll SW. Optimizing stability in distal humeral fracture fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:186S–194S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo Y, Liu W. Treatment of comminuted intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus with double tension band and cancellous screw. Chin J Orthop Trauma. 2005;9:885–887. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali AM, Hassanin EY, El-Ganainy AE, Abd-Elmola T. Management of intercondylar fractures of the humerus using the extensor mechanism-sparing paratricipital posterior approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:747–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrader MW (2008) Pediatric supracondylar fractures and pediatric physeal elbow fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 39:163–71 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wong AS, Baratz ME. Elbow fractures: distal humerus. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoellen IP, Bauer G, Holbein O. Prosthetic humeral head replacement in dislocated humerus multi-fragment fracture in the elderly—an alternative to minimal osteosynthesis? Zentralbl Chir. 1997;122:994–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pajarinen J, Bjorkenheim JM. Operative treatment of type C intercondylar fractures of the distal humerus: results after a mean follow-up of 2 years in a series of 18 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:48–52. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.119390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinzl L, Fleischmann W. The treatment of distal upper arm fractures. Unfallchirurg. 1991;94:455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burg A, Berenstein M, Engel J et al (2010) Fractures of the distal humerus in elderly patients treated with a ring fixator. Int Orthop doi:10.1007/s00264-009-0938-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Boykin RE, Baskies MA, Harrod CC, Jupiter JB. Intraoperative distraction in the upper extremity. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2009;13:75–81. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e31818f0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert SR, Conklin MJ. Presentation of distal humerus physeal separation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:816–819. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31815a060b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollock JW, Athwal GS, Steinmann SP. Surgical exposures for distal humerus fractures: a review. Clin Anat. 2008;21:757–768. doi: 10.1002/ca.20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabezies EJ, D’Ambrosia R. Fracture treatment for the multiply injured patient. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blum J, Gercek E, Hansen M, Rommens PM. Operative strategies in the treatment of upper limb fractures in polytraumatized patients. Unfallchirurg. 2005;108:843–849. doi: 10.1007/s00113-005-1003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu S, Huang C, Zhang M. Surgical treatment of humeral condylar fractures. Chin J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;16:208. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang KH, Park HW, Park SJ, Jung SH. Lateral J-plate fixation in comminuted intercondylar fracture of the humerus. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:234–238. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0508-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei W, Zhang T, Xin J. The treatment and its results of type C fractures of distal humerus. Chin J Orthop. 2005;25:679–681. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarty LP, Ring D, Jupiter JB. Management of distal humerus fractures. Am J Orthop. 2005;34:430–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prokopis PM, Weiland AJ. The triceps-preserving approach for semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:454–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hausman M, Panozzo A (2004) Treatment of distal humerus fractures in the elderly. Clin Orthop Relat Res 425:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Brauer CA, Lee BM, Bae DS, Waters PM, Kocher MS. A systematic review of medial and lateral entry pinning versus lateral entry pinning for supracondylar fractures of the humerus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:181–186. doi: 10.1097/bpo.0b013e3180316cf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Athwal GS, Rispoli DM, Steinmann SP. The anconeus flap transolecranon approach to the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:282–285. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang TL, Chiu FY, Chuang TY, Chen TH. The results of open reduction and internal fixation in elderly patients with severe fractures of the distal humerus: a critical analysis of the results. J Trauma. 2005;58:62–69. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000154058.20429.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JJ, Ruan HJ, Wang JG, Fan CY, Zeng BF. Double-column fixation for type C fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kundel K, Braun W, Wieberneit J, Ruter A (1996) Intraarticular distal humerus fractures. Factors affecting functional outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 332:200–208 [PubMed]

- 27.Gofton WT, MacDermid JC, Patterson SD, Faber KJ, King GJ. Functional outcome of AO type C distal humeral fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:294–308. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaPorte DM, Murphy MS, Moore JR. Distal humerus nonunion after failed internal fixation: reconstruction with total elbow arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2008;37:531–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cil A, Veillette CJ, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey BF. Linked elbow replacement: a salvage procedure for distal humeral nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1939–1950. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad N, Dent C. Outcome of total elbow replacement for distal humeral fractures in the elderly: a comparison of primary surgery and surgery after failed internal fixation or conservative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:343–348. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B3.18971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]