Abstract

Bone matrix mineralisation plays a critical role in the determination of the overall biomechanical competence of bone. However, the molecular mechanisms of bone matrix mineralisation have not been fully elucidated. We used a proteomic approach to identify proteins and genes that may play a role in osteoblast matrix mineralisation. Proteomic differential display revealed a protein band that appeared only in mineralising mouse 7F2 osteoblasts. In-gel protein digestion and mass spectrometry proteomic analysis of this protein band identified 16 proteins. Furthermore, their corresponding transcripts were upregulated. This identification of proteins that may be associated with bone matrix mineralisation presents important new information toward a better understanding of the precise mechanisms of this process.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is characterised by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture. Besides bone mass and microarchitecture it has become evident in recent years that bone mineral and matrix tissue properties play a pivotal role in the overall mechanical competence of bone [1]. Bone matrix mineralisation is an important determinant of the stiffness and hardness of the bone material [2]. Osteoblasts undergo proliferation and maturation that leads to the accumulation and mineralisation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in the form of hydroxyapatite [3]. Transcriptional control of osteoblast growth and differentiation is tightly regulated both temporally and spatially [4]. Some factors, such as mineral-binding-extracellular matrix proteins and proteoglycans, mineralisation-inhibiting proteins and matrix-vesicles [3] are known. However, very little is still known about the molecular control of bone matrix mineralisation. An enhanced understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying bone matrix mineralisation may provide the means to manipulate this process for therapeutic benefit. The use of gene microarrays has recently offered some insight into the global patterns of gene expression in osteoblast matrix mineralisation in vitro [5], as well as osteoblast and osteoclast regulation [6]. However, protein levels depend not only on the levels of the corresponding mRNA but also on a host of translational controls and regulated degradation [7]. Thus proteomics, which allows a holistic view of complex biological processes in the post-genomic era, was employed to identify proteins and genes that may play a role in osteoblast matrix mineralisation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Proliferating mouse 7F2 osteoblasts (American Tissue Culture Collections) were grown in 12-wells tissue culture plates and were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle alpha modification (αMEME) containing 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine and 10% FBS. For osteoblast matrix mineralisation, cells were induced with osteogenic medium for three weeks. Induced and non-induced cells were collected after three weeks of induction.

Detection of matrix mineralisation

Cells were fixed and stained with 1% alizarin red (pH 4.1) for 20 min followed by extensive washing with water to remove the unincorporated dye. Osteocalcin (OST) is an osteoblast matrix mineralisation marker expressed at the transition to osteocytes [8]. OST expression was assayed by real-time RT-PCR using the following forward and reverse primers: 5’ gct tgg ccc aga cct agc aga c 3’; 5’ cca aag ccg agc tgc ca gag 3’.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Proteomic differential display was used to analyse mineralising osteoblasts. Cells were collected by scraping in PBS and resuspended in CyQuant® cell lysis buffer (Invitrogen). The cells were then subjected to three cycles of freeze and thaw and centrifuged at maximum speed (13 k rpm). The clear lysates were collected, evaluated and used for electrophoresis. Then gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, destained and imaged on a flatbed scanner.

Proteomic analysis

The protein band (D1525) was excised from the gel and sent to the Children's Hospital Boston Proteomic Research Facility for protein identification according to standard protocols.

Total RNA extraction and mRNA purification

To have enough RNA, cells from three wells were homogenised together in TRIzol® (Invitrogen), mixed with chloroform, and RNA was precipitated with isopropanol. After quantification, the RNA integrity was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. Total RNA from three different experiments were pooled together before mRNA purification to get enough mRNA for reverse transcription. Oligotex® (Qiagen), mRNA purification reagent, was used to purify mRNA from total RNA according to standard protocols.

Reverse transcription of mRNA and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

RETROscript™ (Ambion), first strand synthesis kit, was used to reverse transcribe the mRNA to cDNA according to standard protocols. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was used to evaluate mRNA as previously described [9] Table 1 lists gene specific primers. Levels of GAPDH transcript proved to be stable under the experimental trials; therefore, it was selected as a reference gene. Relative Expression Software Tool (REST©) was used to analyse mRNA expression levels (Ct values) [10].

Table 1.

Gene specific primers sequence

| Gene | Primers sequence |

|---|---|

| Candidate genes | |

| High density lipoprotein | F:cca gcc ccc tct tca tct tc; R:cct gcc cta ggc tcc tca ac |

| Nucleobindin 1 | F:ttc cag gct cag cct ctc tg; R:tga agc cag gga agt tgg tg |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | F:agg ctg tgg gtc gag cta ag; R:agg aac caa agg cag gaa ag |

| Protein disulfide IA 3 | F:tcc ctg gcc ctg aga tac tg; R:tgc cag cga ttg ata ctg ttt c |

| Transketolase | F:cct tga gct ccg cat gtc ag; R:tca cct cc acct gct gtg ag |

| Prolyl 4-hydroxylase α2 | F:ggc tgc aag tgg gtc tcc aac; R:acc gtg ccg ggt gct ata gtc |

| Endoplasmin | F:agg gga ggt cac ctt caa gtc; R:ccg aac tcc ttc cag aaa gtg |

| Pyruvate kinase muscle | F:cct ggc tct gga ttc acc aac; R:cgc cct tct gtg ata aag tca g |

| Prolyl 4-hydroxylase α1 | F:ggc tcc tgt tgt cct cta acg; R:gct cct gac ttg tgg tga aat c |

| Vimentin | F:agg ccg agg aat ggt aca ag; R:gtg gcg atc tca atg tcc ag |

| Calreticulin | F:agc tgg ctg ctc cca ata atg; R:ccc ctt ctc ctg ccc tcc tc |

| Lamin A/C | F:gct cct ctg cct gcc tta cc; R:caa tcg ccg cac ctc tag ac |

| Lysyl-tRNA synthestase | F:gga gcg ctt tga gct gtt tg; R:tgg tcg ctg cag ttt cct tc |

| Coronin | F:cac tcc gga tgc tgg tca ag; R:ttg ggc agg tcg agg aga tg |

| Phosphoglucomutase 1 | F:gaa gct gtt ccc caa cag aaa g; R:cta tgg ccc gca aga ttt tg |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate CK2 | F:cag gct ggc tcc aaa ctc ac; R:ccc ctg ctg ccc ata tac ac |

| House keeping gene | |

| GAPDH | F:atc tga cgt gcc gcc tgg ag; R:ggt ggg tgg tcc agg gtt tc |

Western blotting

At transcriptional levels, nucleobindin 1 was the most upregulated and calreticulin was one of the low upregulated genes. Therefore, western blotting was used to evaluate their protein expression levels. The antibody for calreticulin was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), nucleobindin 1 antibody was from Protein Tech Group Inc. (Chicago, IL) and β-actin antibody from Ambion.

Results

Detection of matrix mineralisation

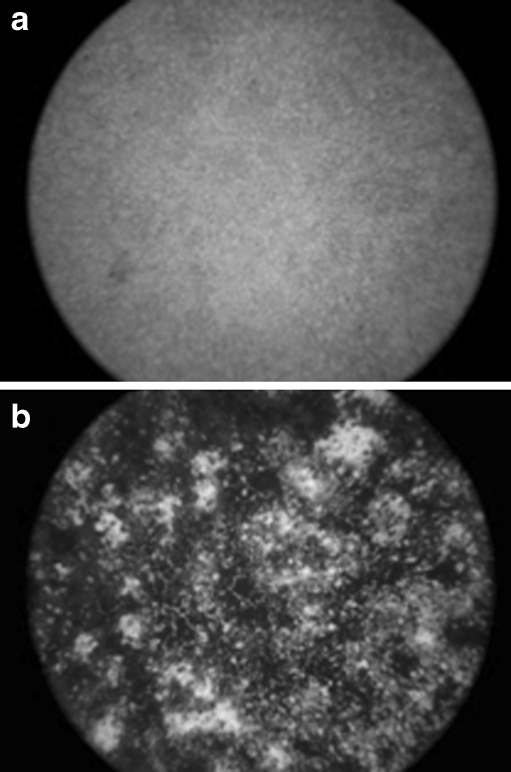

Alizarin red staining of differentiating osteoblasts revealed visible matrix mineralisation at three weeks after induction (Fig. 1). Osteocalcin (OST), an osteoblast matrix mineralisation marker expressed in mineralising osteocytes, was upregulated 1.9-fold in induced versus non-induced osteoblasts (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Alizarin red staining of (a) non-induced and (b) induced osteoblasts at three weeks

Fig. 2.

Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis. Gene transcriptional upregulation in mineralising osteoblasts

Gel electrophoresis and proteomic analysis

Proteomic differential display of differentiating osteoblasts and whole cell lysate revealed a protein band (D1525) of about 60 KDa that appears only in induced mineralising osteoblasts (Fig. 3). In-gel protein digestion and mass spectrometry proteomic analysis of this protein band identified 16 proteins (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Proteomic analysis of mineralising and non mineralising osteoblasts. Lane M Prestained protein marker. Lane A Non induced osteoblasts at three weeks. Lane B Induced osteoblasts at three weeks. Protein band (D1525 labelled with arrow) was excised for protein identification

Table 2.

Proteomic analysis of mineralising osteoblasts

| Gene | Peptide | Score |

|---|---|---|

| High density lipoprotein, Vigilin | TKDLIIEQR | 60.05 |

| Nucleobindin 1 precursor, NUCB1 | LSQETEALGR | 81.36 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1, PGK1 | ITLPVDFVTADKFDENAK | 72.66 |

| Protein disulfide isomerase A3, PDIA3 | MDATANDVPSPYEVK | 101.82 |

| Transketolase, TKT | NMAEQIIQEIYSQVQSK | 91.71 |

| Prolyl 4-hydroxylase α2, P4Ha2 | TAELLQVANYGMGGQYEPHFDFSR | 142.87 |

| Endoplasmin, GRP | GVVDSDDLPLNVSR | 72.90 |

| Pyruvate kinase muscle, PKM2 | LAPITSDPTEAAAVGAVEASFK | 110.78 |

| Prolyl 4-hydroxylase α1, P4Ha1 | IQDLTGLDVSTAEELQVANYGVGGQYEPHFDFAR | 133.06 |

| Vimentin, VIM | LHDEEIQELQAQIQEQHVQIDVDVSKPDLTAALR | 122.04 |

| Calreticulin, CALR | IDNSQVESGSLEDDWDFLPPKK | 97.47 |

| Lamin A/C, LMNa | LADALQELR | 92.83 |

| Lysyl-tRNA synthestase, KARS | ITYHPDGPEGQAYEVDFTPPFRR | 41.34 |

| Coronin 1B, CRN1b | SGASTATAVTDVPSGNLAGAGEAGKLEEVMQELR | 85.69 |

| Phosphoglucomulase 1, PGM1 | INQDPQVMLAPLISIALK | 82.08 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 | EIVSFGSGYGGNSLLGKK | 88.79 |

Gene transcription profiling

Sybr green I real-time RT-PCR was employed to evaluate the transcriptional levels of the predicted 16 genes at the osteoblast mineralisation phase (three weeks after induction or no induction, which confirms the upregulation of their corresponding transcripts; Fig. 2).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was used to evaluate protein expression levels of nucleobindin 1 and calreticulin. Figure 4 shows that calreticulin and nucleobindin1 are upregulated in mineralising osteoblasts at protein levels, which confirms the real-time PCR results.

Fig. 4.

Western blotting analysis. Lane A Non induced. Lane B Induced osteoblasts after three weeks

Discussion

Proteomic profiling provides an efficient method to determine protein candidates and elucidate the signalling transduction pathways in the process of osteoblast matrix mineralisation. Therefore, we used proteomic differential display and mass spectrometry to identify proteins that may be involved in osteoblast matrix mineralisation.

Three of the 16 genes identified in this study (vimentin, calreticulin and lamin a/c) have been noted to have biological functions in osteoblast differentiation. The roles of the other thirteen proteins in osteoblast matrix mineralisation are poorly understood. Nucleobindin 1 (Nucb1), a multifunctional Ca2+ binding protein [11], interacts with nucleic acids and regulatory proteins in several signalling pathways [12]. Although Nucb1 is linked to Ca2+ homeostasis, its functions are largely unknown [13]. Transketolase (Tkt) activity requires divalent metal ion and thiamin diphosphate. It controls the non-oxidative part of the pentose phosphate pathway [14]. Tkt was among the 52 upregulated proteins responsible for the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts [15]. Coronin 1b (CRN1b) is an actin binding protein, which has been involved in a variety of cellular processes that include fibroblast migration [16].

Protein disulfide isomerase associated 3 (Pdia3), a Ca2+ binding and storage protein, resides in the endoplasmic reticulum [17]. It forms a complex with αVβ3 integrin to mediate cell adhesion [18]. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 (PCK2) is a gluconeogenic enzyme involved in glyceroneogenesis [19]. PCK2 is expressed in a variety of human tissues including liver, fibroblasts, intestines, pancreas and kidneys [20]. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase α1 (P4ha1) plays a role in collagen biosynthesis [21], while prolyl 4-hydroxylase α2 (P4ha2) plays a major role in collagen triple helix stabilisation [22]. Type 2 pyruvate kinase (PKM2) modulates glucose metabolism [23]. Phosphoglucomutase 1 (PGM1) is a regulatory enzyme in glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis [24].

High density lipoprotein (Viglin) is an RNA binding protein localised to the cytoplasm and nucleus. Vigilin is expressed in cartilage and bone forming cells as chondrocytes and osteoblasts [25]. Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (Pgk1) is expressed in developing tooth and plays a role in tooth germ development [26]. Lysyl-tRNA synthestase (KARS) is a regulator of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) transcriptional activities [27]. Endoplasmin (GRP), a glucose regulated protein of 94 kDa (Grp94), resides in the endoplasmic reticulum and has effects on cellular Ca2+ storage [28].

Our identification of proteins that may be associated with bone matrix mineralisation presents important information leading to a better understanding of the precise mechanisms of biomineralisation and may provide the means to manipulate this process for therapeutic benefit.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Melvin Glimcher, Lila Graham and Patrick O’Neill for their critical reading of the manuscript and Marie Torres for her assistance in proteomic analysis. This work was supported by grants from The Peabody Foundation to Melvin J. Glimcher.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fratzl P, Gupta HS, Paschalis EP, Roschger P. Structure and mechanical quality of the collagen-mineral nano-composite in bone. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:2115–2123. doi: 10.1039/b402005g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckwalter JA, Glimcher MJ, Cooper RR, Recker R. Bone biology. Part I: structure, blood supply, cells, matrix, and mineralisation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77-A:1256–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glimcher MJ. The nature of the mineral component of bone and the mechanism of calcification. In: Griffin PP, editor. AAOS Instr Course Lect XXXVI. Park Ridge: AAOS Press; 1987. pp. 49–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein GS, Lian JB, Stein JL, Wijnen AJ, Montecino M. Transcriptional control of osteoblast growth and differentiation. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:593–629. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi M, Nagano A, Nakamura Y. Genome-wide screening by cDNA microarray of genes associated with matrix mineralisation by human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:381–390. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borovecki F, Pecina-Slaus N, Vukicevic S. Biological mechanisms of bone and cartilage remodelling–genomic perspective. Int Orthop. 2007;31(6):799–805. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu P, Vogel C, Wang R, Yao X, Marcotte EM. Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:117–124. doi: 10.1038/nbt1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguila HL, Rowe DW. Skeletal development, bone remodeling, and hematopoiesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;208:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofstaetter JG, Saad FA, Samuel RE, Wunderlich L, Choi YH, Glimcher MJ. Differential expression of VEGF isoforms and receptors in knee joint menisci under systemic hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin P, Le-Niculescu H, Hofmeister R, McCaffery JM, Jin M, Hennemann H, McQuistan T, Vries L, Farquhar MG. The mammalian calcium-binding protein, nucleobindin (CALNUC), is a Golgi resident protein. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1515–1527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valencia CA, Cotten SW, Duan J, Liu R. Modulation of nucleobindin-1 and nucleobindin-2 by caspases. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsukumo Y, Tomida A, Kitahara O, Nakamura Y, Asada S, Mori K, Tsuruo T. Nucleobindin 1 controls the unfolded protein response by inhibiting ATF6 activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29264–29272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenk G, Duggleby RG, Nixon PF. Properties and functions of the thiamin diphosphate dependent enzyme transketolase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:1297–1318. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang AX, Yu WH, Ma BF, Yu XB, Mao FF, Liu W, Zhang JQ, Zhang XM, Li SN, Li MT, Lahn BT, Xiang AP. Proteomic identification of differently expressed proteins responsible for osteoblast differentiation from human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;304:167–179. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai L, Makhov AM, Bear JE. F-actin binding is essential for coronin 1B function in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 10):1779–1790. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucero HA, Lebeche D, Kaminer B. ER calcistorin/protein-disulfide isomerase acts as a calcium storage protein in the endoplasmic reticulum of a living cell. Comparison with calreticulin and calsequestrin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9857–9863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahav J, Gofer-Dadosh N, Luboshitz J, Hess O, Shaklai M. Protein disulfide isomerase mediates integrin-dependent adhesion. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:89–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beale EG, Harvey BJ, Forest C. PCK1 and PCK2 as candidate diabetes and obesity genes. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;48:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Modaressi S, Brechtel K, Christ B, Jungermann K. Human mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2 gene. Structure, chromosomal localization and tissue-specific expression. Biochem J. 1998;333(Pt 2):359–366. doi: 10.1042/bj3330359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeowell HN, Murad S, Pinnell SR. Hydralazine differentially increases mRNAs for the alpha and beta subunits of prolyl 4-hydroxylase whereas it decreases pro alpha 1(I) collagen mRNAs in human skin fibroblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;289:399–404. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90430-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nissi R, Böhling T, Autio-Harmainen H. Immunofluorescence localization of prolyl 4-hydroxylase isoenzymes and type I and II collagens in bone tumours: type I enzyme predominates in osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas, whereas type II enzyme predominates in their benign counterparts. Acta Histochem. 2004;106:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Chang Y, Zhang L, Feng Q, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Zuo J, Meng Y, Fang F. High glucose upregulates pantothenate kinase 4 (PanK4) and thus affects M2-type pyruvate kinase (Pkm2) Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;277:117–125. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-5535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gururaj A, Barnes CJ, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Regulation of phosphoglucomutase 1 phosphorylation and activity by a signaling kinase. Oncogene. 2004;23:8118–8127. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plenz G, Gan Y, Raabe HM, Mueller PK. Expression of vigilin in chicken cartilage and bone. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;273:381–389. doi: 10.1007/BF00312841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda JY, Kobayashi I, Kiyoshima T, Yamaza H, Xie M, Takahashi K, Enoki N, Nagata K, Nakashima A, Sakai H. Glycolytic enzyme Pgk1 is strongly expressed in the developing tooth germ of the mouse lower first molar. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:423–432. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YN, Nechushtan H, Figov N, Razin E. The function of lysyl-tRNA synthetase and Ap4A as signaling regulators of MITF activity in FcepsilonRI-activated mast cells. Immunity. 2004;20:145–151. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biswas C, Ostrovsky O, Makarewich CA, Wanderling S, Gidalevitz T, Argon Y. The peptide-binding activity of GRP94 is regulated by calcium. Biochem J. 2007;405:233–241. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]