Abstract

We have undertaken a meta-analysis of the English literature, to assess the component alignment outcomes after imageless computer assisted (CAOS) total knee arthroplasty (TKA) versus conventional TKA. We reviewed 23 publications that met the inclusion criteria. Results were summarised via a Bayesian hierarchical random effects meta-analysis model. Separate analyses were conducted for prospective randomised trials alone, as well as for all randomised and observational studies. In 20 papers (4,199 TKAs) we found a reduction in outliers rate of approximately 80% in limb mechanical axis when operated with the CAOS. For the coronal femoral and tibial implants positions, the analysis included 3,058 TKAs. The analysis for the femoral implant showed a reduction in outliers rate of approximately 87% and for the tibial implant a reduction in outliers rate of approximately 80%. Imageless navigation when performing TKA improves component orientation and postoperative limb alignment. The clinical significance of these findings though has to be proven in the future.

Introduction

Knee pain is a common complaint in older adults. Estimates of self-reported annual prevalence range from 33% (pain on most days for one month or longer) [1] to 47% (pain in or around the knee in the last year) [2]. The definitive treatment for knee osteoarthrosis is total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [3]. The demand for this operation in the United States in 2005 was 450,000 procedures yearly and it is projected to grow to 3.48 million procedures annually by 2030 [4]. The success of TKA is dependent on multiple factors, including patient characteristics, implant selection, operative technique, component positioning, and limb alignment [5]. It has been shown that there is a positive correlation between a good clinical result and a well positioned prosthesis [6, 7]. Proper coronal alignment has been correlated with good clinical outcomes, whereas malalignment of more than 3° of varus or valgus results in a higher failure rate [8–10].

Computer assisted orthopaedic surgery (CAOS) was first introduced in 1999 by Krackow et al. Its objective is to improve the accuracy of implant positioning and extremity alignment [11–13]. CAOS for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is gaining popularity among orthopaedic surgeons. Currently, there are three main categories of navigation systems: intra-operative, image-free (no CT or radiograph) navigation systems; pre-operative, image-based (CT-based) navigation systems; and intra-operative, image-based (radiograph no CT) systems [14]. Image-free navigation is gaining in popularity since it avoids the time, expense and radiation associated with pre-operative CT, and the extra OR time and personnel required for intra-operative radiographs.

Despite the initial enthusiasm there is still disagreement among orthopaedic surgeons regarding the effectiveness of imageless navigation systems to improve the radiological and clinical outcome of TKA [15–19]. Considering the absence of evidence consistently supporting the use of imageless CAOS to improve limb alignment and implant coronal position, we carried out a meta-analysis of trials comparing TKA outcomes with the use of imageless CAOS to the conventional technique.

Methods

Data sources and trial selection

We identified reports of clinical trials that compared imageless navigated knee arthroplasty with conventional total knee arthroplasty, regardless of the underlying condition or disease. An electronic search was conducted covering all the major medical databases (Medline, EMBASE, SciSearch, Scopus and the Cochrane library) entering the following terms and Boolean operators: “total knee replacement”, “alignment”, “navigation”, “imageless”, “image-free”, “outcome”, “computer assisted” until October 2008.

Two authors (Y.S.B. and V.S.N.) identified abstracts which discussed any type of comparison between imageless CAOS and conventional TKRs. These abstracts and their accompanying articles were then paired down to those that compared the mechanical axes and the coronal implant position with CAOS versus conventional TKA and those that compared the outliers in each of the mentioned angles. In a third step, authors D.Z. and J.A. checked the reference lists of the articles to identify citations to articles missed by the search steps. Finally, some articles were rejected because they reported insufficient data, used non-standardised scoring systems, or lacked precise comparison methods.

The study was limited to publications in English literature. We included randomised controlled trials, nonrandomised cohort studies, retrospective studies and studies that used a historical cohort. We included all types of TKR prostheses and all types of imageless navigation systems. This allowed us to compare the overall outcome of imageless CAOS and conventional TKR without being biased by the use of specific types of prostheses or types of equipment used.

Statistical analysis

Differences in trial methods, patients’ characteristics and investigators’ practice patterns mean that the effect of CAOS within each of these trials is unlikely to be identical, as would be implied by the use of a fixed-effects meta-analysis model. We therefore used a Bayesian hierarchical (random effects) model to summarise the data across trials, thereby accounting for between-trial variations in odds ratios. In this model, the probability (p) of an event (outlier greater than 2 or 3 degrees) within each group of each trial is allowed to vary both between the treatment and control groups within each study and between each study included in the meta-analysis. To model the between-study variability, the logarithms of the odds ratios of each outcome variable are assumed to follow a normal distribution. The mean of the normal distribution of log odds ratios across studies therefore represents the average effect in the studies, and the variance represents the variability among the studies. Low-information prior distributions were used throughout, so that the data from the trials dominate the final inferences. Inferences were calculated using a Gibbs sampler algorithm programmed in WinBUGS software (version 1.4.1, MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). Forest plots for all major outcomes, which display the odds ratios and 95% credible intervals (Bayesian analogue of frequentist confidence intervals) for both the individual trials based on the random effects meta-analytic model, and for the pooled results from our meta-analysis.

For each outcome, we performed two meta-analyses, one incorporating data from randomised clinical trials alone, and a second analysis using data from all studies, including both randomised trials and observational studies.

Results

Out of 46 publications identified for screening, the electronic search yielded 23 publications that met the inclusion criteria and were considered eligible for the study. In two studies the authors did not calculate the outliers rate of the mechanical limb axis [20, 21], but in one of them the outliers for the components were calculated [20], so it was included in our meta-analysis for the evaluation of the implant position only. In the remaining 21 studies, one of the studies used a cut-off angle for the mechanical limb angle as ±2° or more [22]. There were 4,063 patients with 4,163 TKRs. Ten trials were prospective and randomised [22–31]. Table 1 is a descriptive table that summarises the various trial characteristics and participant demographics. First we analysed the prospective randomised studies alone. Then we analysed all the studies together and compared the results. The results were similar for both analyses.

Table 1.

Trial characteristics

| Author | Study type | Navigation system | Knees | Males | Females | Age conventional | Age navigation | Mechanical axis > ±3° | Femoral angle > ±3° | Tibial angle > ±3° | Operating time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenny and Boeri [32] | Retrospective | Aesculap | C = 30 N = 30 |

21 | 39 | C = 9 N = 5 |

C = 5a N=2a |

C = 6a N=2a |

C = 90 N=110 |

||

| Sparmann et al. [23] | Prospective randomised | Stryker | C=120 N=120 |

C = 41 N = 32 |

C = 79 N = 88 |

66.1 | 64.7 | C=16 N = 0 |

C = 34 N=1 |

C=12 N=1 |

|

| Bahtis et al. [24] | Prospective randomised | BrainLAB | C = 80 N = 80 |

C=27 N=21 |

C = 53 N = 59 |

70.9 ± 9.1 | 68.7 ± 9.3 | C=18 N = 3 |

C=11 N = 6 |

C = 5 N=2 |

C = 64 ± 11 N = 78 ± 12 |

| Chauhan et al. [25] | Prospective randomised | Stryker | C = 35 N = 35 |

C=10 N = 5 |

C = 3 N = 0 |

C = 3 N = 0 |

C = 67 N = 80 |

||||

| Matsumoto et al. [26] | Retrospective matched pared control study | Brain LAB | C = 30 N = 30 |

C = 5 N = 5 |

C=25 N=25 |

73.3 | 75.3 | C=10 N=2 |

C = 9a N=2a |

C = 7a N=2a |

|

| Haaker et al. [33] | Retrospective | Aesculap | C=100 N=100 |

C = 74 N = 66 |

C=26 N = 34 |

69 | 68 | C = 72 N=21 |

C=101 ± 21 N=111 ± 22 |

||

| Daubresse et al. [34] | Retrospective | Aesculap. | C = 50 N = 50 |

C=15 N=19 |

C = 35 N = 31 |

61 | 63 | C=16 N = 0 |

C = 3 N = 0 C=13a N = 5a |

C = 0 N = 0 C=10a N = 0a | |

| Zorman et al. [35] | Prospective study compared to a historical cohort | BrainLAB | C = 62 N = 72 |

C=19 N = 0 |

C=12 N = 0 |

C = 7 N = 0 |

|||||

| Decking et al. [22] | Prospective randomised | Aesculap. | C=25 N=27 |

C = 8 N = 9 |

C=17 N=18 |

67.3 ± 6.3 | 64.7 ± 9.4 | C=16a N=13a |

C = 5a N = 5a |

C = 5a N=1a |

C = 79 ± 8 N = 92 ± 9 |

| Kim et al. [36] | Prospective study compared to a historical cohort. | Stryker | C = 69 N = 78 |

C=26 N=23 |

C = 54 N = 44 |

68 | 70 | C=19 N = 4 |

|||

| Bolognesi and Hofman [49] | Retrospective | Navitrack | C = 50 N = 50 |

C=21 N=24 |

C=27 N=26 |

C = 5 N=1 | C = 4 N = 0 | ||||

| Jenny et al. [37] | Retrospective | Aesculap | C=235 N=235 |

107 | 363 | C = 65 N=18 |

C = 54 N=26 |

C = 41 N=26 |

C = 99 ± 22 N=108 ± 22 |

||

| Beneyto et al. [38] | Prospective randomised multicenter study | Stryker | C = 84 N=102 |

72.3 | 71.6 | C = 59 N = 53 |

C = 76.9 N = 93.6 |

||||

| Ensini et al. [27] | Prospective randomised | Stryker | C = 60 N = 60 |

C=20 N = 30 |

C = 40 N = 30 |

71.1 ± 7.8 | 68.8 ± 6.3 | C=15 N = 7 |

C = 9 N = 0 |

C=2 N=1 |

|

| Matziolis et al. [28] | Prospective randomised | Pigalielo | C=28 N = 32 |

20 | 40 | 70 ± 9 | 71 ± 7 | C = 7 N=1 |

C = 3 N = 0 |

C = 5 N = 0 |

C = 94 ± 18 N=101 ± 17 |

| Martin et al. [29] | Prospective randomised | BrainLAB | C=100 N=100 |

C=27 N = 32 |

C = 73 N = 68 |

71.1 ± 7.5 | 70.3 ± 8.2 | C=24 N = 8 |

C=14 N = 5 |

C=15 N = 3 |

C = 68 ± 18 N = 88 ± 16 |

| Mullaji et al. [30] | Prospective randomised | Brain LAB | C=185 N=282 |

C = 47 N = 67 |

C=143 N=215 |

65.9 | 65.5 | C = 40 N=26 |

|||

| Kim et al. [15] | Prospective- | BrainLAB | C=100 N=100 |

C=15 N=15 |

C = 85 N = 85 |

C = 35 N=28 |

C = 9 N=13 |

C = 7 N=16 |

C = 82 N = 97 |

||

| Tingart et al. [39] | Prospective study | Brain LAB | C = 500 N = 500 |

C=137 N=156 |

C = 363 N = 344 |

70.8 ± 9.4 | 67.3 ± 8.9 | C=128 N=26 |

C=159 N=20 |

C=105 N=23 |

C = 78 ± 23 N = 86 ± 20 |

| Oberst et l. [31] | Prospective randomised | Brain LAB | C = 35 N = 34 |

C = 7 N=2 |

|||||||

| Rosenberger et al. [40] | Retrospective | Medtronic | C = 50 N = 50 |

C=14 N=15 |

C = 36 N = 35 |

66.92 ± 7.48 | 65.63 ± 6.83 | C=21 N = 5 |

C = 6 N=1 |

C=10 N=2 |

|

| Yau et al. [16] | Retrospective | BrainLAB | C = 52 N = 52 |

C = 5 N = 8 |

C=28 N=25 |

66.3 ± 7.6 | 69 ± 9.2 | C=13 N=15 |

C = 3 N = 3 |

C = 5 N = 7 |

C conventional, N navigation

a The outlier angle was measured as >2°

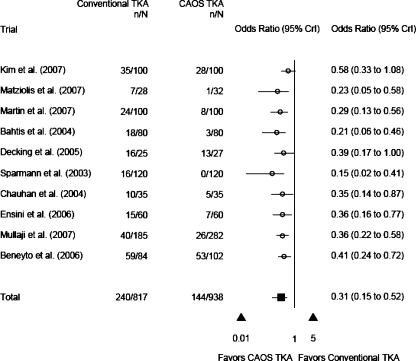

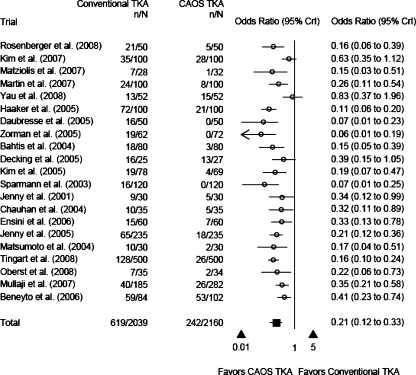

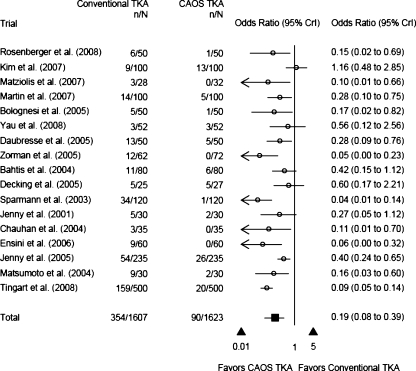

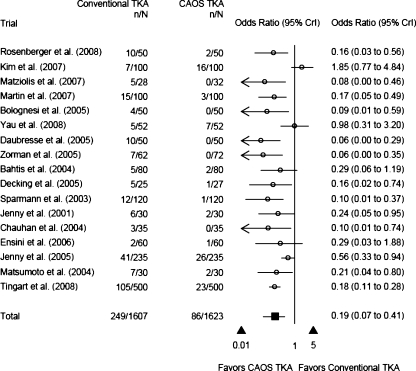

Results of meta-analysis for prospective randomised studies alone are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Table 3 presents the results of the meta-analysis for all the studies combined. Figures 2, 3 and 4 graphically present the results for the limb mechanical axis, femoral angle, and tibial angle, respectively.

Table 2.

Outliers reduction rate for the different angles, calculated only for the prospective randomised studies

| Angle | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| HKA angle > ±3° | 0.289 | 0.116–0.524 |

| HKA angle > ±2° and ± 3° | 0.313 | 0.149– 0.517 |

| coronal femoral angle > ±3° | 0.106 | 0.008–0.866 |

| coronal femoral angle > ±2° and ± 3° | 0.149 | 0.016–0.878 |

| coronal tibial angle > ±3° | 0.19 | 0.020–1.144 |

| coronal tibial angle > ±2° and ±3° | 0.188 | 0.028–0.828 |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, HKA hip-knee-ankle

Fig. 1.

Mechanical axis diagram for prospective randomised studies alone

Table 3.

Outliers reduction rate for the different angles, calculated for all studies (prospective randomised and retrospective)

| Angle | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| HKA angle > ±3° | 0.201 | 0.111–0.324 |

| HKA angle > ±2° and ± 3° | 0.211 | 0.123–0.333 |

| coronal femoral angle > ±2° | 0.345 | 0.057–1.87 |

| coronal femoral angle > ±3° | 0.13 | 0.036–0.344 |

| coronal femoral angle > ±2° and ± 3° | 0.19 | 0.077–0.392 |

| coronal tibial angle > ±2° | 0.112 | 0.005–1.395 |

| coronal tibial angle > and ±3° | 0.206 | 0.057–0.521 |

| coronal tibial angle > ±2° and ± 3° | 0.19 | 0.068–0.411 |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, HKA hip-knee-ankle

Fig. 2.

Mechanical axis diagram for prospective randomised and retrospective studies

Fig. 3.

Femoral angle diagram for prospective randomised and retrospective studies

Fig. 4.

Tibial angle diagram for prospective randomized and retrospective studies

In 20 papers (4,199 TKAs) the outlier cut-off angle for the mechanical axis was defined as ±3° from the neutral [15, 16, 23–41]. For these trials, in 2,039 cases the conventional technique was used and the other 2,160 cases were operated with imageless CAOS. There were 390 (18.6%) outliers for the mechanical axis in the conventional group compared to 92 (4.3%) in the CAOS group. The meta-analysis estimated an odds ratio of OR = 0.201 (95% CI 0.111–0.324). This represents a strong effect, with CAOS reducing outlier rate by approximately 80%. The effect was similar when we combined the data with the one study where the chosen cut-off value was 2° (OR = 0.211; 95% CI 0.123–0.333) (Tables 2, 3; Figs. 1 and 2).

For the coronal femoral and coronal tibial implants position, 14 studies defined the outlier cut-off as ±3° or more. The analysis included 1,522 patients in the conventional group and 1,536 in the CAOS group. Analysing the femoral implant position revealed 280 (18.4%) patients in the conventional group that had outliers in femoral implant position, compared to 48 (3.1%) in the CAOS group. The meta-analysis estimated better results with the CAOS TKA. With a cut-off of 3° we found OR = 0.13 (95% CI 0.036–0.344), implying a strong effect with reducing the outliers rate by approximately 87% when using the CAOS (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 3).

Four studies defined the outlier cut-off for coronal femoral implants as ±2° [22, 26, 32, 34]. They included 272 operated knees. One hundred thirty-five were operated upon using the conventional technique and 137 with CAOS. The results for the femoral implant showed 32 (23.7%) outliers in the conventional group compared to 14 (10.2%) in the CAOS group. The meta-analysis resulted in a wide 95% CI (0.057–1.87), that precludes definitive conclusion. When we combined studies with cut-off value of 3° or more with those whose cut-off values were 2° or more, the result was OR = 0.19 (95% CI 0.077–0.392). This result shows a reduction in the outlier rate for the coronal femoral implant angle by approximately 81% (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 3).

The tibial implant analysis with cut-off value of ±3° or more exhibited outliers in 185 (12.2%) conventional cases, compared to 53 (3.5%) in the CAOS group. The results of the meta-analysis were conclusive for the coronal tibial angle, showing better results when CAOS was used. The reduction rate of outliers was approximately 80% (OR = 0.206; 95% CI 0.057–0.521) in favour of the CAOS. In the four studies with cut-off angle of ±2° or more the result of the meta-analysis showed a wide 95% CI which precludes definitive conclusions. When the two values for cut-off were combined, the result showed a reduction rate of approximately 81% (OR = 0.19; 95% CI 0.068–0.411) in outliers (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 4).

The study results reveal that 1,065 (51%) women were operated upon with CAOS and 1,021 by the conventional technique. Among men, 516 (52%) were operated upon with the assistance of CAOS and 477 by the conventional technique. In four studies with another 459 operated knees, the authors did not mention the patients’ gender (Table 1). These numbers show that in the total population of patients that underwent TKA and that were included in the studies, no gender bias for CAOS or conventional technique occurred.

Finally, we observed increased mean operating time comparing CAOS TKA to conventional TKA, with an average difference of 24.7 minutes (95% CI −9.0, 58.6) when all studies were included, and a difference of 13.6 minutes (95% CI −28.6, 56.5) when only randomised studies were included. However, the wide credible intervals mean that further study is required to see if the effect arose by chance or not.

Discussion

The most important conclusion of this meta-analysis is that the usage of imageless CAOS for TKA significantly reduces the number of outliers in the limb mechanical axis and coronal position of the implants by a rate of approximately 80%. This can be an important message for decision makers in health care systems, since better surgical results may, in the long run, mean less revision operations, hence considerable savings in human suffering and cost.

CAOS has drawbacks that are well described, including the increased operative time (of 20 minutes on average) and the extra costs for hardware and software usage and disposable parts that need to be purchased [15, 22, 24, 25, 28, 29, 33, 37–39, 32, 42, 43]. With imageless CAOS for TKA surgeons avoid exposing patients to the extra radiation associated with pre-operative CT, and avoid the extra OR time and personnel required for intra-operative radiographs [14]. Because of these advantages imageless CAOS is continuously gaining in popularity and thus we wanted to perform a meta-analysis of imageless CAOS studies only.

Two previous meta-analyses investigated the effectiveness of the navigated TKA versus the conventional [44, 45]. These studies concluded better results for navigated TKA and have analysed prospective randomised studies, but also quasi-randomised controlled trials, nonrandomised cohort studies, studies with historical cohorts, and studies investigating the outcome of computed tomography or image-free navigation systems for both unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. However, these meta-analyses included comparative studies of both imageless and CT-based navigation systems.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis in the literature analysing only image-free navigation systems. We included both prospective randomised studies and others. We ran separate analyses for the prospective randomised studies only and subsequently for all the studies combined. We found similar results whether the studies were prospectively randomised or not, so we concluded that there might not be a bias effect for the non prospective randomised studies, although it could serve as a point for criticism to our study. Finally, our meta-analysis evaluated only English written studies that were published until October 2008.

This meta-analysis evaluates studies with different navigation systems (Table 1). All are image-free navigation systems and there might be differences between them. We could not separate the meta-analysis for each manufacturer because of the small number of studies done with each separate system. Since all share the same principles of image-free CAOS, we decided it would be reasonable to include them all in one meta-analysis. In the future, with more studies, there will be a place to consider a meta-analysis for one kind of navigation system only

The cut-off value for outliers in this meta-analysis was 3° or 2°. These are the values that are used in the studies that we evaluated. Indeed, these cut-off values have proven to be significantly correlated to the long-term survivorship of TKA [8–10]. Others have shown that coronal malalignment of greater than 3° can reduce TKA ten-year survival from 90% to 73% [8, 46]. Nevertheless, despite this evidence, the clinical significance of the use of CAOS TKA is still debated. Spenser et al. showed no difference in the following clinical scores: knee society score, WOMAC score, Oxford knee score and Bartlett patellar score, between navigated and conventional TKA patients in a prospective randomised study with up to two years of follow-up [47]. Ensini et al. failed to show a better clinical improvement up to 28 months after the operation using the Oxford score, patellofemoral joint score, and satisfaction score [27]. Anderson et al. did not find any improvement in range of motion at six months follow-up [48]. Finally, Decking et al. showed the same clinical results at three months following the operation using the WOMAC score and the Knee Society score [22]. These studies show that although there are better outcomes in alignment and implant position in CAOS TKA, there is no effect on the clinical outcome in the short-term follow-up. We believe that the influence of a better limb alignment and implant position will be realised only after several years. Since CAOS TKA was first introduced in 1999 [11], there is not enough data available yet to show a reduction in implant failure rate when CAOS is used. Further studies and longer survey of patients and outcomes will be necessary to prove that.

Limitations of this study warrant further discussion. First, we included studies with different levels of evidence and not randomised studies only. Using non-randomised studies might introduce a bias. In this study, we first performed a meta-analysis for randomised studies and only then a second meta-analysis for randomised and non-randomised studies. We found the same results, so we concluded that there is probably no bias in the non-randomised studies, hence we could use both studies in the meta-analysis. Second, we concentrated only on the limb mechanical axis and the coronal angle of the femoral and tibial components, but did not evaluate the sagittal plane of the implants. Third, our data did not evaluate clinical differences between the two modalities. This data could be evaluated only in the future. Fourth, we included data that was collected from different navigation systems of different manufacturers. However, all of them followed the same principle, i.e. image-free navigation systems.

Conclusions

Results of this meta-analysis showed that the use of imageless CAOS for TKA significantly reduces the number of outliers in the limb mechanical axis and coronal position of the implants by a rate of approximately 80%. It should be taken into account that there are some drawbacks with CAOS including the cost, length of surgery, learning curve, etc. However, CAOS TKA seems to improve accurate component positioning; the clinical significance of this remains to be proven.

Source of funding

The authors declare that there was no external funding source for this study.

References

- 1.Dawson J, Linsell L, Zondervan K, Rose P, Randall T, Carr A, Fitzpatrick R. Epidemiology of hip and knee pain and its impact on overall health status in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:497–504. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jinks C, Jordan K, Ong BN, Croft P. A brief screening tool for knee pain in primary care (KNEST). 2. Results from a survey in the general population aged 50 and over. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:55–61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAlindon T, Zucker NV, Zucker MO. 2007 OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: towards consensus? Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16:636–637. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1487–1497. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stulberg SD, Loan P, Sarin V. Computer-assisted navigation in total knee replacement: results of an initial experience in thirty-five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(Suppl 2):90–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Influence of positioning of prosthesis in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter MA, Faris PM, Keating EM, Meding JB (1994) Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res 299:153–156 [PubMed]

- 8.Jeffery RS, Morris RW, Denham RA. Coronal alignment after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:709–714. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B5.1894655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hvid I, Nielsen S. Total condylar knee arthroplasty. Prosthetic component positioning and radiolucent lines. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:160–165. doi: 10.3109/17453678408992329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berend ME, Ritter MA, Meding JB, Faris PM, Keating EM, Redelman R, Faris GW, Davis KE (2004) Tibial component failure mechanisms in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 428:26–34 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Krackow KA, Bayers-Thering M, Phillips MJ, Mihalko WM. A new technique for determining proper mechanical axis alignment during total knee arthroplasty: progress toward computer-assisted TKA. Orthopedics. 1999;22:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiehl JB. Comparison of tibial rotation in fixed and mobile bearing total knee arthroplasty using computer navigation. Int Orthop. 2009;33:679–685. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0562-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luring C, Oczipka F, Grifka J, Perlick L. The computer-assisted sequential lateral soft-tissue release in total knee arthroplasty for valgus knees. Int Orthop. 2008;32:229–235. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merloz P. Computer-assisted knee replacement. European Instructional Course Lectures. 2008;8:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YH, Kim JS, Yoon SH. Alignment and orientation of the components in total knee replacement with and without navigation support: a prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:471–476. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yau WP, Chiu KY, Zuo JL, Tang WM, Ng TP. Computer navigation did not improve alignment in a lower-volume total knee practice. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:935–945. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik MH, Wadia F, Porter ML. Preliminary radiological evaluation of the Vector Vision CT-free knee module for implantation of the LCS knee prosthesis. Knee. 2007;14:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamat YD, Aurakzai KM, Adhikari AR, Matthews D, Kalairajah Y, Field RE. Does computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty improve patient outcome at midterm follow-up? Int Orthop. 2009;33:1567–1570. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0690-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bejek Z, Solyom L, Szendroi M. Experiences with computer navigated total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2007;31:617–622. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0254-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mombert M, Daelen L, Gunst P, Missinne L. Navigated total knee arthroplasty: a radiological analysis of 42 randomised cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stockl B, Nogler M, Rosiek R, Fischer M, Krismer M, Kessler O (2004) Navigation improves accuracy of rotational alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 426:180–186. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Decking R, Markmann Y, Fuchs J, Puhl W, Scharf HP. Leg axis after computer-navigated total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized trial comparing computer-navigated and manual implantation. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sparmann M, Wolke B, Czupalla H, Banzer D, Zink A. Positioning of total knee arthroplasty with and without navigation support. A prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:830–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bathis H, Perlick L, Tingart M, Luring C, Zurakowski D, Grifka J. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty. A comparison of computer-assisted surgery with the conventional technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:682–687. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B5.14927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauhan SK, Scott RG, Breidahl W, Beaver RJ. Computer-assisted knee arthroplasty versus a conventional jig-based technique. A randomised, prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:372–377. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B3.14643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto T, Tsumura N, Kurosaka M, Muratsu H, Kuroda R, Ishimoto K, Tsujimoto K, Shiba R, Yoshiya S. Prosthetic alignment and sizing in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2004;28:282–285. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0562-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ensini A, Catani F, Leardini A, Romagnoli M, Giannini S. Alignments and clinical results in conventional and navigated total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:156–162. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180316c92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matziolis G, Krocker D, Weiss U, Tohtz S, Perka C. A prospective, randomized study of computer-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty. Three-dimensional evaluation of implant alignment and rotation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:236–243. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin A, Wohlgenannt O, Prenn M, Oelsch C, Strempel A. Imageless navigation for TKA increases implantation accuracy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:178–184. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31804ea45f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullaji A, Kanna R, Marawar S, Kohli A, Sharma A. Comparison of limb and component alignment using computer-assisted navigation versus image intensifier-guided conventional total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, single-surgeon study of 467 knees. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberst M, Bertsch C, Konrad G, Lahm A, Holz U. CT analysis after navigated versus conventional implantation of TKA. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:561–566. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenny JY, Boeri C. Computer-assisted implantation of total knee prostheses: a case-control comparative study with classical instrumentation. Comput Aided Surg. 2001;6:217–220. doi: 10.3109/10929080109146086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haaker RG, Stockheim M, Kamp M, Proff G, Breitenfelder J, Ottersbach A (2005) Computer-assisted navigation increases precision of component placement in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 433:152–159 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Daubresse F, Vajeu C, Loquet J. Total knee arthroplasty with conventional or navigated technique: comparison of the learning curves in a community hospital. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zorman D, Etuin P, Jennart H, Scipioni D, Devos S. Computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty: comparative results in a preliminary series of 72 cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:696–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SJ, MacDonald M, Hernandez J, Wixson RL. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: improved coronal alignment. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenny JY, Clemens U, Kohler S, Kiefer H, Konermann W, Miehlke RK. Consistency of implantation of a total knee arthroplasty with a non-image-based navigation system: a case-control study of 235 cases compared with 235 conventionally implanted prostheses. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macule-Beneyto F, Hernandez-Vaquero D, Segur-Vilalta JM, Colomina-Rodriguez R, Hinarejos-Gomez P, Garcia-Forcada I, Seral Garcia B. Navigation in total knee arthroplasty. A multicenter study. Int Orthop. 2006;30:536–540. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tingart M, Luring C, Bathis H, Beckmann J, Grifka J, Perlick L. Computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty versus the conventional technique: how precise is navigation in clinical routine? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberger RE, Hoser C, Quirbach S, Attal R, Hennerbichler A, Fink C. Improved accuracy of component alignment with the implementation of image-free navigation in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0420-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jenny JY. The current status of computer-assisted high tibial osteotomy, unicompartmental knee replacement, and revision total knee replacement. Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:721–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graydon AJ, Malak S, Anderson IA, Pitto RP. Evaluation of accuracy of an electromagnetic computer-assisted navigation system in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2009;33:975–979. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0586-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seon JK, Park SJ, Lee KB, Li G, Kozanek M, Song EK. Functional comparison of total knee arthroplasty performed with and without a navigation system. Int Orthop. 2009;33:987–990. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0594-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, Gebhard F, Hanson B, Ekkernkamp A, Stengel D. Navigated total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:261–269. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rand JA, Coventry MB (1988) Ten-year evaluation of geometric total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 232:168–173 [PubMed]

- 47.Spencer JM, Chauhan SK, Sloan K, Taylor A, Beaver RJ. Computer navigation versus conventional total knee replacement: no difference in functional results at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:477–480. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson KC, Buehler KC, Markel DC. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: comparison with conventional methods. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolognesi M, Hofmann A. Computer navigation versus standard instrumentation for TKA: a single-surgeon experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:162–169. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000186561.70566.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]