Abstract

Among social vertebrates, immigrants may incur a substantial fitness cost when they attempt to join a new group. Dispersers could reduce that cost, or increase their probability of mating via coalition formation, by immigrating into groups containing first- or second-degree relatives. We here examine whether dispersing males tend to move into groups containing fathers or brothers in gray-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena) in Kibale National Park, Uganda. We sampled blood from 21 subadult and adult male mangabeys in 7 social groups and genotyped them at 17 microsatellite loci. Twelve genotyped males dispersed to groups containing other genotyped adult males during the study; in only 1 case did the group contain a probable male relative. Contrary to the prediction that dispersing males would follow kin, relatively few adult male dyads were likely first- or second-degree relatives; opportunities for kin-biased dispersal by mangabeys appear to be rare. During 4 yr of observation, adult brothers shared a group only once, and for only 6 wk. Mean relatedness among adult males sharing a group was lower than that among males in different groups. Randomization tests indicate that closely related males share groups no more often than expected by chance, although these tests had limited power. We suggest that the demographic conditions that allow kin-biased dispersal to evolve do not occur in mangabeys, may be unusual among primates, and are worth further attention.

Keywords: Dispersal, Gray-cheeked mangabeys, Kibale National Park, Lophocebus albigena, Microsatellites, Relatedness

Introduction

For many social primates, dispersal and subsequent immigration into a new group can have substantial fitness costs (Isbell and van Vuren 1996; Pusey and Packer 1987). In addition to costs related to increased predation risk and decreased knowledge of food resources, immigrants may receive aggression from group residents, e.g., olive baboons (Papio anubis): Packer (1979); long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis): van Noordwijk and van Schaik (1985); Hanuman langurs (Semnopithecus entellus): Borries (2000); and white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus): Fedigan (1993). Resident male olive baboons herd females away from immigrant males, and may also chase these males, sometimes severely wounding them (Packer 1979). Further, immigrants may also initially take on low ranking positions in the existing dominance hierarchy, e.g., vervets (Cercopithecus aethiops): Henzi and Lucas (1980); long-tailed macaques: van Noordwijk and van Schaik (1985); and Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata): Sprague (1992).

Given that access to kin increases the likelihood of forming coalitions and may decrease the probability of aggression, researchers have often suggested that dispersers could reduce fitness costs by immigrating with relatives (Cheney and Seyfarth 1983; Johnson and Gaines 1990; Ross 2001). In some species, relatives, or familiar individuals suspected of being relatives, immigrate into groups together, e.g., rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): Drickamer and Vessey (1973); Japanese macaques: Kawanaka (1973); yellow baboons (Papio hamadryas cynocephalus): Cheney and Seyfarth (1977); vervets: Cheney and Seyfarth (1983); squirrel monkeys (Saimiri boliviensis): Mitchell (1994); and white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus): Jack and Fedigan (2004). For example, male squirrel monkeys emigrate from their natal groups with age-mates, often spending time together in all-male bands before eventually entering new mixed-sex groups with the same individuals (Mitchell 1994). Male coalitions are essential for gaining entry into a group, and for maintaining membership in it (Jack and Fedigan 2004). Genetically related immigrant male rhesus macaques are more likely to support each other in aggressive interactions and to reach high-ranking positions in the dominance hierarchy than are males that immigrate alone (Meikle and Vessey 1981). Even singly dispersing individuals of some species immigrate into groups containing relatives, e.g., vervets: Cheney and Seyfarth (1983) and western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla): Bradley et al. (2007). For example, male vervets immigrate into groups containing related males, which decreases the likelihood that resident males and females will be aggressive toward them. In addition, young males sometimes immigrate together with peers or brothers (Cheney and Seyfarth 1983). Female western gorillas are more likely to immigrate into groups containing female relatives, making female kin associations possible (Bradley et al. 2007).

Gray-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena) are arboreal, forest relatives of the widely studied savanna baboons (Papio spp.), and have become a common subject of behavioral research (Arlet et al. 2007; Chancellor and Isbell 2009; Janmaat et al. 2006; O’Driscoll-Worman and Chapman 2006; Olupot et al. 1994; Waser 1977). As in baboons, macaques, and many other cercopithecine primates, male mangabeys generally leave their natal groups just before reproductive maturity, often spending many months alone before successfully joining another group. A stable, matrilineal core of 6.2 ± 0.8 adult females can be joined by 3.1 ± 1.2 adult males (Olupot and Waser 2010), but male tenure in groups varies widely (Olupot and Waser 2005). Adult males often make individual forays to neighboring groups, shadowing them for a few hours or days, and when they are able to maintain prolonged contact with the new group’s females, those visits can progress to secondary dispersal. Not surprisingly, resident males are often aggressive toward visitors, and the males that succeed in immigrating into the new group are those able to mate in the new group despite the harassment they receive (Olupot and Waser 2001a, b). If the intensity of aggression received by a “visiting” male from resident males is influenced by their relatedness to him, his ability to enter and mate in a new group might be influenced by the presence of close male relatives.

Between 1996 and 2000, Olupot darted and radiocollared males in Kibale National Park, Uganda, documenting many aspects of dispersal and providing an opportunity to examine the role of kinship in male dispersal decisions. We here estimate the coefficient of relatedness among adult males based on blood samples collected during the process of attaching radiocollars, and then document the degree to which males join groups containing possible male relatives. Based on previous studies of closely related species (Cheney and Seyfarth 1983) and the theoretical advantages of male coalition formation, we predicted that dispersing male mangabeys would follow kin. Although 2 microsatellite markers for gray-cheeked mangabeys have already been developed (Clisson et al. 2000), the species is not well characterized genetically and it was necessary for us to evaluate additional markers and compare them with baboons and macaques.

Methods

Subjects

Between 1996 and 1998, Olupot darted and radiocollared all 25 adult male residents of 7 adjacent social groups in the vicinity of the Makerere University Biological Field Station, Kibale National Park, Uganda. He also darted subadult males, solitary males, and immigrants when possible. He scored males as adult or subadult based on body mass and dentition, and took 1–2 ml of whole blood from each individual (Olupot 2000a, b; Olupot and Waser 2005) Through mid-2000, he located and observed each male with an operating radiocollar 2–3× per week, thereby documenting male associations with social groups and each other as well as naturally occurring dispersal events (Olupot and Waser 2001a, b, 2005). Some blood was used for viral assays, but samples from 21 males (18 adult, 3 subadult) remained in 2007 and we transferred these samples to the Molecular Anthropology Laboratory at the University of California, Davis for genetic analyses.

Markers

We extracted DNA from whole blood samples using the QiaAmp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s directions. The close genetic relationship between gray-cheeked mangabeys and other cercopithecines, particularly Papio (Fleagle and McGraw 1999; Page and Goodman 2001), suggested that cross-amplification would be possible, and we selected 17 loci proven to be informative in Papio or Macaca for genotyping. For polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, we used 1.25 μl of DNA extract in each 12.5-μl reaction (67 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.8, 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.01% Tween-20, 0.05 mM each dNTP, 0.2 μM each primer, 1.7 mM MgSO4, 0.025 units/ml of Invitrogen Platinum Taq). We optimized annealing temperatures and extension times of the thermocycling conditions to each microsatellite primer pair (Table I), but generally included 60 cycles with denaturing at 94°C for 20 s, a variable annealing time and temperature, extension at 72°C for 45–90 s, and a variable final extension time at 72°C. We analyzed all samples on the ABI 3130 DNA Sequencer with the Liz 500 size standard, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Three of the markers (D7s1826, D7s794, and D8s1106) had a 6-base-pair “pig tail” on the reverse primer. We adjusted allele sizes for these markers accordingly.

Table I.

Primer sequences and annealing temperatures for Lophocebus albigena markers

| Locus name | Forward and reverse primer sequences | Anneal/ext/final ext |

|---|---|---|

| D2s1333 | 3′: CTT TGT CTC CCC AGT TGC TA | 62°C/30 s/60 min |

| 3′: TCT GTC ATA AAC CGT CTG CA | ||

| D3s1768 | 3′: GGT TGC TGC CAA AGA TTA GA | 60°C/45 s/60 min |

| 3′: CAC TGT GAT TTG CTG TTG GA | ||

| D4s243 | 3′: TCA GTC TCT CTT TCT CCT TGC A | 60°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: TAG GAG CCT GTG GTC CTG TT | ||

| D5s820 | 3′: ATT GCA TGG CAA CTC TTC TC | 56°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GTT CTT CAG GGA AAC AGA ACC | ||

| D5s1457 | 3′: TAG GTT CTG GGC ATG TCT GT | 58°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: TGC TTG GCA CAC TTC AGG | ||

| D6s501 | 3′: GCT GGA AAC TGA TAA GGG CT | 58°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GCC ACC CTG GCT AAG TTA CT | ||

| D7s1826 | 3′: CAT CCA TCT ATC TCT GTA ATC TCT C | 60°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GTT CTT TAT TTA ACA CAC CTG TCT CAA TCC | ||

| D7s794 | 3′: GCC AAT TCT CCT AAC AAA TCC | 60°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GTT CTT TAT GCC CAT GTG TTA GGG TT | ||

| D8s1106 | 3′: TTG TTT ACC CCT GCA TCA CT | 60°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GTT CTT TTC TCA GAA TTG CTC ATA GTG C | ||

| D11s2002 | 3′: CAT GGC CCT TCT TTT CAT AG | 60°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: AAT GAG GTC TTA CTT TGT TGC C | ||

| AGAT007 | 3′: CAA TGT TAA CTG ACT GCA TTG CTG | 60°C/45 s/60 min |

| 3′: TGG AAG CTA CAA TTC AAG ATG AGA | ||

| 270o7 | 3′: GAG CTC TGT GGA TTG CTG TGT AGA TTT | 62°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GGC ACG TGC CTG TAG TCC CAG TTA T | ||

| 272o12 | 3′: GTG TTC ATC TGG GAA TTT | 54°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GCT AGC TAA CTA GAC AGG TAG TT | ||

| D10s611 | 3′: CAT ACA GGA AAC TGT GTA GTG C | 64°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GTT CTT CTG TAT TTA TGT GTG TGG ATG G | ||

| D14s306 | 3′: AAA GCT ACA TCC AAA TTA GGT AGG | 54°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: TGA CAA AGA AAC TAA AAT GTC CC | ||

| D16s750 | 3′: ATA GCA AGT ACT GAA TGA CCT GG | 52°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GCA AAG CAC TGG GAG ATT TA | ||

| D4s1626 | 3′: TAC ACT TGA ACA AAG TAA GGA TGC | 60°C/45 s/5 min |

| 3′: GTT CTT AAA GGA AAA GGA ATG GGA TG |

The ABI 3130 DNA Sequencer initially assigned allele sizes to the hundredth base pair. As it is impossible for an individual to have an allele size of less than a whole base pair, we rounded the decimal values either up or down to the nearest base pair, and identified any 2 bands differing by <1 base pair as the same allele. Because all markers included in this study contained tetranucleotide (4-base pair, bp) repeat motifs, fragment sizes that are multiples of 4 were expected, though not required because insertions or deletions can increase or decrease the motif length by ≥1 bps. When we identified individuals with alleles that met the criteria above, but did not exhibit solely alleles that represented the 4-bp repeat motif, we regenotyped the individual at that locus until a concordant genotype was produced from ≥2 independent PCR reactions.

To test for allelic dropout and misidentification of heterozygotes, we randomly selected one third of individuals and regenotyped for every marker, and compared the replicate genotypes to the original. If the 2 genotypes matched, we considered the assignment correct. If the genotypes were not the same, e.g., the individual was a homozygote in the first PCR and a heterozygote in the second, we regenotyped the individual until ≥2 concordant genotypes were produced.

We estimated population genetic parameters from genotypic data with the adegenet 1.1 package for R. We used ML-RELATE, which generates maximum likelihood estimates of genetic relatedness, r (Kalinowski et al. 2006), to assess genetic relationships between all pairs of males. In addition, the program uses k-coefficients, or probabilities that a dyad shares 0, 1, or 2 alleles (Blouin 2003) in common, to estimate the relative likelihoods that individuals are siblings, parent and offspring, or unrelated.

We generated mean relatedness values within and between groups by averaging the estimates of r between each male and each of the other males in or out of his group, creating a single measure for each individual to avoid pseudoreplication. To compare the mean relatedness of individuals within and between groups, we performed a Wilcoxon signed-ranks test.

Randomization Tests

We performed a randomization test to determine whether the observed rate of dispersal into groups containing relatives was greater than expected by chance. For each observed dispersal by a genotyped male, we determined which of the adjacent 5 focal groups contained ≥1 adult male related to the emigrant by r > 0.20 at the time he left his group. We chose this cutoff to include first- (0.50, as with full brothers or fathers and sons) and second (0.25)-degree relatives (as with half-brothers) but exclude dyads of lower relatedness; for convenience, we refer to males whose estimated r > 0.20 as relatives. We then simulated the same number of dispersal events, in each case choosing a destination for the male randomly from the adjacent 5 groups. For each dispersing individual in turn, we recorded whether his random new group contained a male relative, iterating this process 1000 times. This procedure yielded the number of times that mangabeys dispersing without regard to the presence of relatives would be expected to immigrate into a group containing ≥1 relative by chance alone.

Estimators of genetic relatedness and relationship are subject to considerable error (Blouin 2003; Csillery et al. 2006; Van Horn et al. 2008). For example, Van Horn et al. (2008), using a larger data set than ours but a similar number of microsatellite loci, found that 3.5% of baboon dyads classified as unrelated were in reality close relatives, but that only 58% of dyads classified as related actually were. To assess whether our estimate of the number of males dispersing into groups containing relatives was sensitive to those errors, we performed another randomization test. We reassigned relatedness to our dyads on the assumption that errors in our analyses were of similar magnitude, converting a random 5% of our unrelated dyads, as determined by our genetic analysis, to relatives and 40% of our related dyads to nonrelatives. We then counted how many times dispersing males entered groups containing relatives as defined by this procedure, and iterated the process 1000 times.

Finally, we randomized the distribution of adult males among the 7 study groups in June of each year (1997–2000), maintaining the observed number of males in each group, and counting the number of pairs of males related by r > 0.20. Again, we iterated this process 1000 times. This gave us the number of pairs expected to share a group if males chose groups without regard to relatedness.

Results

Markers

We obtained genotypes at all 17 loci for 18/21 males; 3 males failed to amplify at 1 locus each. Lophocebus albigena was monomorphic at loci D3s1768 and AGAT007. Two polymorphic loci exhibited a significant excess of homozygotes, suggesting the presence of null alleles, and were eliminated from estimates of r. The remaining 13 polymorphic loci were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, and a number of alleles per locus ranging from 2 to 6 (Table II); we used these loci for relatedness analyses.

Table II.

Summary of genetic data collected for Lophocebus albigena, compared with values for Papio hamadryas anubis and Macaca mulatta

| Lophocebus (N = 21) | Papio (N = +100) | Macaca (N = 392) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus name | No. of alleles | Min. Size | Max. size | H e | H o | No. of alleles | Min. size | Max. size | H o | No. of alleles | Min. size | Max. size | H o |

| D2s1333 | 5 | 282 | 298 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 10 | 278 | 314 | 0.86 | 19 | 265 | 349 | 0.49 |

| D3s1768 | 1 | 158 | 158 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 178 | 230 | 0.80 | 19 | 174 | 226 | 0.75 |

| D4s243 | 5 | 160 | 176 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 8 | 153 | 181 | 0.76 | – | – | – | – |

| D5s820 | 6 | 195 | 230 | 0.75 | 0.62 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D5s1457 | 4 | 121 | 133 | 0.64 | 0.76 | – | – | – | – | 13 | 113 | 141 | 0.50 |

| D6s501 | 3 | 176 | 184 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 17 | 174 | 238 | 0.85 | 12 | 169 | 237 | 0.58 |

| D7s1826 | 3 | 137 | 150 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 10 | 122 | 158 | 0.79 | 10 | 126 | 158 | 0.53 |

| D7s794 | 3 | 144 | 157 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 11 | 146 | 183 | 0.66 | 10 | 145 | 185 | 0.57 |

| D8s1106 | 3 | 154 | 162 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 10 | 131 | 167 | 0.79 | 20 | 128 | 212 | 0.60 |

| D11s2002 | 3 | 263 | 298 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 8 | 254 | 282 | 0.79 | 10 | 250 | 282 | 0.46 |

| AGAT007 | 1 | 164 | 164 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 157 | 189 | 0.81 | 14 | 157 | 189 | 0.64 |

| 270o7 | 2 | 195 | 99 | 0.04 | 0.05 | – | – | – | – | 9 | 177 | 220 | 0.58 |

| 272o12 | 6 | 148 | 165 | 0.71 | 0.32 | – | – | – | – | 9 | 138 | 162 | 0.78 |

| D10s611 | 4 | 152 | 164 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 18 | 149 | 213 | 0.91 | 13 | 170 | 222 | 0.76 |

| D14s306 | 4 | 162 | 182 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 10 | 156 | 188 | 0.78 | 14 | 157 | 158 | 0.72 |

| D16s750 | 4 | 97 | 102 | 0.61 | 0.27 | – | – | – | – | 4 | 100 | 112 | 0.51 |

| D4s1626 | 5 | 158 | 186 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 14 | 232 | 284 | 0.85 | 31 | 162 | 217 | 0.66 |

PHA microsatellite data from the Southwest National Primate Research Center Primate Genetics and Genomics Database (http://baboon.sfbrgenetics.org/Bab_Polymorphisms/STRpageBL.php); MM microsatellite data from Smith et al. (2006)

Table II also includes comparative values for allele number, allele size range, and observed heterozygosity at each locus for captive olive baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis) at the Southwest National Primate Research Center and captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from a variety of U.S. and international primate centers. The number of alleles at each locus is substantially lower in our sample of Lophocebus than in either Papio or Macaca. Nevertheless, the observed heterozygosity for Lophocebus is comparable to that observed in Macaca, and overlaps the range of heterozygosities in Papio.

Relatedness and Dispersal

Among the 210 possible pairs among our 21 males, the mean relatedness was r = 0.07. Most pairs were unrelated, but 28 pairs were related by r > 0.20, with a maximum estimated r of 0.58.

Genotyped males dispersed into groups containing other genotyped males 12 times between 1996 and 2000. In 4 of these events, the disperser had no relatives in any adjacent group at the time of dispersal. During the other 8, the disperser had 1–2 possible relatives in neighboring groups, but only once did he enter a group that contained a relative (for this pair, r = 0.30). This result was insensitive to errors associated with estimating genetic relatedness; correcting for relatives misclassified as nonrelatives and vice versa, the mean number of dispersers that entered groups containing males classified as relatives was 1.2 ± 1.0 (mean ± SD). In 68% of our 1000 randomizations, dispersers entered groups containing a relative no more than once.

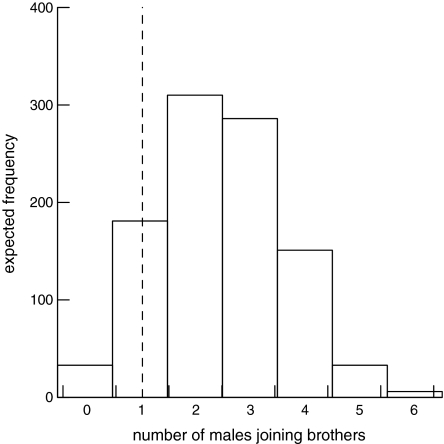

By chance, the number of dispersers expected to enter a group containing a relative was 2.2, and the probability that ≥1 disperser would enter a group containing a relative was 0.93 (Fig. 1). Therefore, males entered a group containing a male relative no more often than expected by chance

Fig. 1.

Expected (histogram from randomization test) and observed (dashed line) number of males that immigrated into groups containing probable brothers during the study.

When we examined the distribution of relatedness within and among social groups, we found that 1 of our 3 genotyped subadults was related by r = 0.50 to an adult male in his group, suggesting that they were a father–son pair. This pair shared the same group for ≥3 of the 4 yr of the study. The other 2 subadult males were not related to any other males in their groups by r > 0.20. The mean r between subadults and other males in their groups was 0.06, virtually identical to their relatedness to males in other groups (r = 0.08).

Excluding the subadults, the mean value of r among males sharing a group was 0.04. For males in different groups, the mean r was 0.08. In other words, relatedness among adult males in the same group was marginally lower (p = 0.04, N = 18, Wilcoxon signed-ranks test) than that among adult males in different groups. This pattern of mean male relatedness, together with that reported above for dyads involving subadult males, provides no support for the idea that dispersal produces clusters of male relatives.

No related adult males shared groups at the start of the study, and the 1 male that immigrated into a group containing an apparent relative stayed only 6 wk before emigrating again. The numbers of pairs of relatives expected to share groups each year by chance were 1.1 (1997), 2.9 (1998, when the observed case occurred), 1.3 (1999), and 1.5 (2000). The probabilities that relatives would share groups at least as often as observed by chance were 0.79 (1997), 0.86 (1998), 0.84 (1999), and 0.86 (2000). Therefore, male relatives shared groups no more often than expected by chance.

Discussion

Markers

Primers for microsatellites polymorphic in other cercopithecines were readily adapted to use with Lophocebus albigena. The number of alleles per locus was relatively low, as might be expected if there is an ascertainment bias, but observed heterozygosities were comparable to those observed in captive populations of olive baboons and rhesus macaques. In light of the Uganda mangabey’s recent assignment by Groves (2007) to its own species (Lophocebus ugandae) based on cranial measurements, it is increasingly relevant to also investigate the genetics of this group of primates.

Opportunities for Kin-biased Dispersal

An unexpected result of our analysis is that only 28/210 (13%) of our dyads have r values high enough to be characterized as likely relatives. In other words, the genetic data suggest that most dispersing mangabeys will not have nearby male kin to follow. As noted earlier, one problem associated with relatedness estimators is that they may be biased. Could the apparent lack of brothers in nearby groups be an artifact of that limitation? In fact, the pattern of type I and type II errors reported by Van Horn et al. (2008), suggest that relatedness estimators overestimate the number of related dyads. If the pattern of errors reported by Van Horn et al. (2008) for baboons also applies to mangabeys, the true percentage of male dyads that are relatives (22/210 = 10%) may be even lower than our estimate (28/210 = 13%). In other words, the pattern of type I and type II errors associated with relatedness estimators reinforces, rather than weakens, the conclusion that opportunities for kin-biased dispersal are rare.

The imprecision of relatedness estimators also places wide confidence limits around our inference that dispersing mangabeys rarely have nearby brothers. Nevertheless, if we use a more permissive definition of relatives, accepting every dyad for which ML-Relate cannot reject sibling as a possible relationship, the proportion of dyads that are related is 38/210 (19%). If we are conservative and accept only dyads for which the hypothesis of no relationship is rejected, the proportion drops to 7/210 (3%). Neither estimate suggests many opportunities for kin-biased dispersal.

How many close male relatives might a disperser be expected to have, given mangabey group size and demography? In the Appendix, we derive the likelihood that a dispersing male mangabey has a living brother. The results confirm our inferences from male genotypes: only one third of male dispersers would be expected to have a living maternal brother somewhere in the population, and at most half would have a living father (Appendix). The proportion of those brothers (or fathers) that might live in nearby groups given dispersal patterns, and the proportion that a dispersing male might be able to recognize are both unknown. Dispersing males might also have older paternal brothers; this likelihood depends on assumptions about the mating system but is at most ca. 0.3 (Appendix). Assuming that the mangabey mating system resembles that of baboons, paternal brothers would likely be age-mates and age can be used as a proxy for relatedness (Alberts 1999); however, the relatively small group size of mangabeys ensures that male age-mates are rare. In 7 groups monitored continuously over 4 yr, none contained more than a single subadult male (W. Olupot unpubl. data).

Relatedness and Dispersal

Opportunities to follow brothers were uncommon, and when they occurred, we found no evidence to support the idea that mangabeys took them. Males dispersed singly, and showed no tendency to target groups containing male relatives. Our finding that only 1 of our dispersing males joined a group containing a male relative was not changed by simulating the pattern of errors in relatedness estimation. Mean relatedness estimates, which are more reliable than estimates of relatedness for particular dyads, indicate that adult males in the same group are significantly less related to each other than to males in other groups. It is difficult to reconcile this result with the idea that males preferentially join groups containing brothers.

Our randomization tests had limited statistical power because of the rarity of adult male relatives. If dispersal were kin-biased, we would have to follow a considerably larger number of dispersal events to document it with certainty. Similarly, we could not statistically reject the hypothesis of kin-biased dispersal. However, in each randomization test we performed, the frequency with which males joined or shared groups with likely brothers was lower, not higher than expected by chance.

Ecology, Demography, and the Evolution of Kin-biased Dispersal

Why do some primate species, but apparently not mangabeys, disperse selectively into groups with relatives? One possibility is that kin-biased dispersal reflects ecological, not social factors. For example, potential dispersal routes are limited by predation in dwarf mongooses (Keane et al. 1996). Dispersers followed restricted routes that had more vegetation or rock cover, and thus ended up in groups with genetically similar individuals (Keane et al. 1996). Leopard predation is a major cause of mortality in vervets (Cheney et al. 1981; Isbell 1990). Following restricted dispersal routes by transferring to adjacent groups in the company of peers may minimize this risk (Cheney and Seyfarth 1983). However, this constraint is unlikely to apply to mangabeys. Predation is higher for solitary than for group-living males, but mangabeys live in continuous-canopy forest and their major predator is the crowned hawk-eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus) (Olupot and Waser 2001a). It is hard to imagine that safe dispersal routes are in short supply. Indeed, Olupot located isolated radiocollared males nearly 1000 times, at locations throughout the study area (Janmaat et al. 2009).

For some species, it is conceivable that inbreeding avoidance prevents kin-biased dispersal (Cavalli-Sforza and Bodmer 1971) because a male that transfers into a small group following his brother may have difficulty avoiding mating with his brother’s daughters. However, mangabey demography (Appendix) suggests that males that follow relatives into a group would at worst breed with their half-brothers’ daughters. The cost of inbreeding with relatives of this magnitude (r = 0.125) is generally small (Keller and Waller 2002). In addition, mangabey females often mate with subordinate as well as dominant males (Arlet et al. 2008b), suggesting that opportunities for outbred matings should be common.

Could dispersing mangabeys avoid aggression by joining brothers? Aggression from residents poses a substantial fitness cost to immigrants in many social species, not only primates (Lambin et al. 2001; Ronce 2007; Waser 1996; Williams and Rabenold 2005). Immigration is a stressful event for the closely related yellow baboon and has been associated with high levels of cortisol (Alberts et al. 1992; Bergman et al. 2005; van Schaik et al. 1991). Competition between male mangabeys strongly predicts cortisol concentrations, with immigrants having higher concentrations than residents (Arlet et al. 2008a). However, we have no data to assess whether the presence of kin reduces aggression toward immigrating males. Our results instead imply that demographic factors strongly influence the evolution of kin-biased dispersal. Where ecology does not constrain dispersal routes, we suggest that kin-biased dispersal is likely to evolve only when 2 conditions are met: 1) patterns of mate competition allow subordinate coalitions to successfully challenge dominants for matings that would not otherwise have gone to either of them and 2) demographic conditions are such that nearby groups often contain male relatives.

Kin-biased dispersal would evolve if males that have already dispersed increase their inclusive fitness by easing their brothers’ entry into their social group (Cheney and Seyfarth 1983). But a male that allowed his brother to immigrate would increase his inclusive fitness only if offspring sired by his brother would not otherwise have been sired by him. Unless brothers join coalitions that displace dominant males from matings they would otherwise monopolize, it is difficult to see how this condition could be met. Kin competition, as well as kin cooperation, influences inclusive fitness (Lambin et al. 2001; Ronce 2007). Indeed, among primates kin-biased dispersal is confined to species in which males commonly form coalitions (rhesus macaques: Drickamer and Vessey 1973; vervets: Cheney and Seyfarth 1983; squirrel monkeys: Mitchell 1994; white-faced capuchins: Jack and Fedigan 2004). The pattern is similar in social carnivores, particularly lions (Packer and Pusey 1993). Male coalitions are common in baboons, allowing subordinate males to improve their probability of mating through coalition formation (Alberts et al. 2006). In contrast, male coalition formation has not been reported in mangabeys (Arlet et al. 2008b). Demography may dilute the value of coalition formation in mangabeys because most groups contain relatively few males (mean = 3.1; Olupot and Waser 2010), and turnover is relatively high (median tenure of an adult male in a group = 17 mo; Olupot and Waser 2005).

Even more fundamentally, kin-biased dispersal cannot evolve unless recognizable kin are available in nearby groups. Genetic and demographic evidence both suggest that this condition is rarely met for mangabeys. Whether it is met in other primates appears not to have been examined; models have examined the impact of demography on expected relatedness within but not between groups (Altmann 1979; Lukas et al. 2005). It is not immediately obvious what mating patterns and birth/mortality schedules will create clusters of male relatives, and we believe this is an issue worthy of more general examination.

Acknowledgments

The American Society of Primatologists, the University of California, Davis Institute for Governmental Affairs, and the University of California, Davis Department of Anthropology provided funding for this study. In Uganda, we thank the Office of the President, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, the Uganda Wildlife Authority, and the Makerere University Biological Field Station for permission to conduct research in Kibale National Park. We thank Andrew DeWoody, Steven Kalinowski, Susan Alberts, Scott Creel, and 2 anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts, and Richard Kaserengenyu, John Rusoke, and Clovice Kaganzi for assistance in the field. Additional laboratory work was conducted by Joy Erickson.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix: The Likelihood of Having a Living Elder Brother

The likelihood that a given male, i, selected at random from the population will have at least one living, elder maternal brother when he disperses can be derived by considering the following 3 components:

- The probability that i is the k th offspring born to his mother. Assuming that twinning never occurs, birth order is a geometric process, equivalent to the number of coin flips that occur before the first heads, i.e., how many births in a family occur before i is born. If females have an average of n live births, then we can assume that p, the probability that any given birth produces i, is p = 1/n. Plugging p into the geometric distribution gives:

1 -

Given that i is the k th offspring in his family, he can have anywhere from zero to k−1 elder brothers. Assuming that an offspring’s sex is random, the number of elder brothers, v, is distributed as a binomial variable with the probability that any given birth produces a male, m = 0.5 for a 1:1 sex ratio at birth. This gives:

2 Note that this probability includes all possible birth-order combinations for the elder brothers. For example, if k = 4 and v = 2, the 2 brothers could be the 1st and 2nd offspring in the family, the 1st and 3rd, or the 2nd and 3rd. All 3 possibilities are included.

-

To be alive when i disperses, a brother must survive the juvenile period (until the age of dispersal) and then survive as an adult over w interbirth intervals, where w is the number of intervals that separate the brother from i. Assuming a constant length for intersbirth intervals, the probability that a brother is not alive when i disperses is:

where s j and s a are the juvenile survival rate and the likelihood that an adult male will survive 1 interbirth interval, respectively. Assuming that i has (k−1) elder siblings and that we do not know their birth order, there is a 1/(k−1) chance that a given brother will have any w value from 1 to k−1. Averaging s a across the possible values for w gives the expected probability that any given elder brother will no longer be alive when i disperses:

The probability that ≥1 brother is still alive is equal to 1 minus the probability that all of the brothers are dead. If i has k−1 elder siblings, v of which are brothers, and each brother’s survival is independent of the others, this is equal to:

The probability that ≥1 brother is still alive is equal to 1 minus the probability that all of the brothers are dead. If i has k−1 elder siblings, v of which are brothers, and each brother’s survival is independent of the others, this is equal to:

3 Combining the equations (1–3) gives an approximate likelihood that a given male will have at least one living maternal half-brother when he disperses. Note that cases where k = 1 or v = 0 do not allow for any elder brothers, and so contribute 0 probability to the sum.

4 The probability that i will have ≥1 living paternal brother can be calculated using the same formula by changing the parameters p and s a to reflect the average number of offspring sired by males and the shorter interval that separates paternal siblings, respectively.

Field data on mangabey demography are scarce. Olupot and Waser (2005) estimated an adult male annual mortality rate of 0.08 in this population. In a captive colony, Deputte (1991) recorded an average of 0.29 live births/yr for each of 9 females over 19 yr, suggesting an interbirth interval, t, of ca. 3 yr. Together, these figures suggest that the survival rate for an adult male over an interbirth interval s a is 0.923 = 0.78.

In the same colony, male masses first exceed those of females at 4 yr and reach a plateau at 7 yr (Deputte 1992), and the first production of the adult male whoop-gobble call, an event coinciding with natal dispersal in the field, occurs at 6–7 yr (Gautier-Hion and Gautier 1976). We infer that the age of natal dispersal is ca. 6 yr. No survival data are available for young male mangabeys, but a rough estimate of survival to reproductive maturity can be taken as s j = 0.5, the survivorship to age 6 reported for male baboons (Alberts and Altmann 2003).

If we assume that the average female has 5 offspring over her lifetime (p = 0.2), that the sex ratio at birth is 1:1 (m = 0.5), and estimate s j and s a from Eq. 4, we estimate the probability that a dispersing male has a living older maternal brother as p(≥1 living maternal brother) = 0.33.

Even fewer data are available for paternal siblings. Mangabey groups in this population contain on average 3.1 adult males and 6.2 females (Olupot and Waser 2010) and mean male tenure length in a group is 1.6 yr (Olupot and Waser 2005). Assuming for simplicity that females come into estrus at evenly spaced intervals (t/number of females), ca. 6.2 × 0.29 = 1.8 females will conceive each year and a male will have 1.6 × 1.8 = 2.88 opportunities to sire an offspring. If males have equal probabilities of paternity, then a male would sire (on average) about 2.88/3.1 = 0.93 offspring in each group, implying no opportunity for paternal siblings. If (as in baboons) paternity is skewed toward dominant males and most dominant males are young, an extreme assumption might be that a male sires all 2.88 young in his first group and none thereafter. In this case, the interbirth interval between paternal siblings would equal 1/1.8 = 0.56 yr. Assuming that the adult male mortality risk is evenly distributed through time (s a = 0.920.56 = 0.95), Eq. 4 yields a likelihood of having ≥1 paternal brother of p(≥1 living paternal brother) = 0.30.

Given that neither maternal nor paternal half brothers will be common at the time of dispersal, living full siblings will be even less so. Finally, if we assume a male first establishes himself in a nonnatal group 7–8 yr after conception, an annual adult male survival rate of 0.92 leads to the probability that his sire will still be alive in the population of 0.928 = 0.51. We note that all of these probabilities will be lower for males that disperse later in life.

References

- Alberts SC. Paternal kin discrimination in wild baboons. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 1999;266:1501–1506. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts SC, Altmann J. Matrix models for primate life history analysis. In: Kappeler PM, Pereira ME, editors. Primate life histories and socioecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003. pp. 66–102. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts SC, Sapolsky RM, Altmann J. Behavioral, endocrine and immunological correlates of immigration by an aggressive male into a natural primate group. Hormones and Behavior. 1992;26:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0018-506X(92)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts SC, Buchan JC, Altmann J. Sexual selection in wild baboons: from mating opportunity to paternity success. Animal Behaviour. 2006;72:1177–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann J. Age cohorts as paternal sibships. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1979;6:161–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00292563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arlet ME, Molleman F, Chapman CA. Indications for female mate choice in grey-cheeked mangabeys Lophocebus albigena johnstoni in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Acta Ethologica. 2007;10:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10211-007-0034-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arlet ME, Grote MN, Molleman F, Isbell LA, Carey JR. Reproductive tactics influence cortisol levels in individual male gray-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena) Hormones and Behavior. 2008;55:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlet, M. E., Molleman, F., & Chapman, C. A. (2008b). Mating tactics in male grey-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena). Ethology, 114, 851–862.

- Bergman TJ, Beehner JC, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Whitten PL. Correlates of stress in free-ranging male chacma baboons, Papio hamadryas ursinus. Animal Behaviour. 2005;70:703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin MS. DNA-based methods for pedigree reconstruction and kinship analysis in natural populations. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2003;18:503–511. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00225-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borries C. Male dispersal and mating season influxes in Hanuman langurs living in multi-male groups. In: Kappeler PM, editor. Primate males: Causes and consequences of variation in group composition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley BJ, Doran-Sheehy DM, Vigilant L. Potential for female kin associations in wild western gorillas despite female dispersal. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274:2179–2185. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Bodmer WF. The genetics of human populations. San Francisco: Freeman; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Chancellor RL, Isbell LA. Female grooming markets in a population of gray-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena) Behavioral Ecology. 2009;20:79–86. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arn117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM. Behaviour of adult and immature male baboons during intergroup encounters. Nature. 1977;269:404–406. doi: 10.1038/269404a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM. Non-random dispersal in free-ranging vervet monkeys: social and genetic consequences. American Naturalist. 1983;122:392–412. doi: 10.1086/284142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, D. L., Lee, P. C., & Seyfarth, R. M. (1981). Behavioral correlates of non-random mortality among freeranging female vervet monkeys. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 9, 153–161.

- Clisson I, Lathuilliere M, Crouau-Roy B. Conservation and evolution of microsatellite loci in primate taxa. American Journal of Primatology. 2000;50:205–214. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(200003)50:3<205::AID-AJP3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csillery K, Johnson T, Beraldi D, Clutton-Brock TH, Coltmann D, Hansson B, et al. Performance of marker-based relatedness estimators in natural populations. Genetics. 2006;173:2091–2101. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.057331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deputte BL. Reproductive parameters of captive grey-cheeked mangabeys. Folia Primatologica. 1991;57:57–69. doi: 10.1159/000156566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deputte BL. Life history of captive grey-cheeked mangabeys: physical and sexual development. International Journal of Primatology. 1992;13:509–531. doi: 10.1007/BF02547830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drickamer LC, Vessey SH. Group-changing in free-ranging rhesus monkeys. Primates. 1973;14:359–368. doi: 10.1007/BF01731357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fedigan LM. Sex differences and intersexual relations in adult white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus) International Journal of Primatology. 1993;14:853–877. doi: 10.1007/BF02220256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleagle JG, McGraw WS. Skeletal and dental morphology supports diphyletic origin of baboons and mandrills. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:1157–1161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier-Hion A, Gautier J-P. Croissance, maturité sexuelle et sociale, et réproduction dans les cercopithicines forestiers africains. Folia Primatologica. 1976;26:165–184. doi: 10.1159/000155749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves CP. The endemic Uganda mangabey, Lophocebus ugandae, and other members of the albigena-group (Lophocebus) Primate Conservation. 2007;22:123–128. doi: 10.1896/052.022.0112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henzi SP, Lucas JW. Observations on the inter-troop movement of adult vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) Folia Primatologica. 1980;33:220–235. doi: 10.1159/000155936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isbell LA. Sudden short-term increase in mortality of vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) due to leopard predation in Amboseli National Park, Kenya. American Journal of Primatology. 1990;21:41–52. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350210105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isbell LA, van Vuren D. Differential costs of locational and social dispersal and their consequences for female group-living primates. Behaviour. 1996;133:1–36. doi: 10.1163/156853996X00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jack KM, Fedigan LM. Male dispersal patterns in white-faced capuchins, Cebus capucinus. Part 1: patterns and causes of natal emigration. Animal Behaviour. 2004;67:761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janmaat KRL, Byrne RW, Zuberbühler K. Evidence for spatial memory of fruiting states of rain forest fruit in wild ranging mangabeys. Animal Behaviour. 2006;71:797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janmaat, K. R. L., Olupot, W., Chancellor, R. L., Arlet, G., & Waser, P. M. (2009). Long-term site fidelity, and individual home range shifts in Lophocebus albigena. International Journal of Primatology, 30, 443–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson ML, Gaines MS. Evolution of dispersal: theoretical models and empirical tests using birds and mammals. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1990;21:449–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.002313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski ST, Wagner AP, Taper ML. ML-Relate: a computer program for maximum likelihood estimation of relatedness and relationship. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2006;6:576–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01256.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanaka K. Intertroop relations among Japanese monkeys. Primates. 1973;14:113–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01730816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keane B, Creel SR, Waser PM. No evidence of inbreeding avoidance or inbreeding depression in a social carnivore. Behavioral Ecology. 1996;7:480–489. doi: 10.1093/beheco/7.4.480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller LK, Waller DM. Inbreeding effects in wild populations. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2002;17:230–240. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02489-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambin X, Aars J, Piertney SB. Dispersal, intraspecific competition, kin competition and kin facilitation: A review of the empirical evidence. In: Clobert J, Danchin E, Dhondt AA, Nichols J, editors. Dispersal. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas D, Reynolds V, Boesch C, Vigilant L. To what extent does living in a group mean living with kin? Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:2181–2196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle DB, Vessey SH. Nepotism among rhesus monkey brothers. Nature. 1981;294:160–161. doi: 10.1038/294160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CL. Migration alliances and coalitions among adult male South American squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) Behaviour. 1994;130:169–190. doi: 10.1163/156853994X00514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll-Worman C, Chapman CA. Densities of two frugivorous primates with respect to forest and fragment tree species composition and fruit availability. International Journal of Primatology. 2006;27:203–225. doi: 10.1007/s10764-005-9007-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W. Darting, individual recognition and radiotracking of grey-cheeked mangabeys Lophocebus albigena in Kibale National Park. African Primates. 2000;4:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W. Mass differences among male mangabey monkeys inhabiting logged and unlogged forest compartments. Conservation Biology. 2000;14:833–843. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98585.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W, Waser PM. Activity patterns, habitat use and mortality risks of mangabey males living outside social groups. Animal Behaviour. 2001;61:1227–1235. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2000.1709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W, Waser PM. Correlates of intergroup transfer in male grey-cheeked mangabeys. International Journal of Primatology. 2001;22:169–187. doi: 10.1023/A:1005615329835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W, Waser PM. Patterns of male residency and intergroup transfer in gray-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena) American Journal of Primatology. 2005;66:331–349. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W, Waser PM. Grey-cheeked mangabey Lophocebus albigena. In: Butynski TM, Kingdon JS, Kalina, editors. The mammals of Africa. Vol. 2. Primates. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Olupot W, Chapman CA, Brown CH, Waser PM. Mangabey (Cercocebus albigena) population density, group size, and ranging: a twenty year comparison. American Journal of Primatology. 1994;32:197–205. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350320306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer C. Intertroop transfer and inbreeding avoidance in Papio anubis. Animal Behaviour. 1979;27:1–36. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(79)90126-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer C, Pusey A. Dispersal, kinship and inbreeding in African lions. In: Thornhill NW, editor. The natural history of inbreeding and outbreeding. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993. pp. 375–391. [Google Scholar]

- Page SL, Goodman M. Catarrhine phylogeny: noncoding DNA evidence for a diphyletic origin of the mangabeys and for a human-chimp clade. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2001;18:14–25. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusey AE, Packer C. Dispersal and philopatry. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT, editors. Primate societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. pp. 250–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ronce O. How does it feel to be like a rolling stone: ten questions about dispersal evolution. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 2007;38:231–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross KG. Molecular ecology of social behaviour: analyses of breeding systems and genetic structure. Molecular Ecology. 2001;10:265–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DG, George D, Kanthaswamy S, McDonough J. Genetic tests to verify the country of origin of, and level of admixture between, Indian and Chinese rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) American Journal of Primatology. 2006;27:881–898. doi: 10.1007/s10764-006-9026-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague JS. Life history and male intertroop mobility in Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) International Journal of Primatology. 1992;13:437–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02547827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn RC, Altmann J, Alberts SC. Can’t get there from here: inferring kinship from pairwise genetic relatedness. Animal Behaviour. 2008;75:1173–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk MA, van Schaik CP. Male migration and rank acquisition in wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Animal Behaviour. 1985;33:849–861. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80019-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik CP, van Noordwijk MA, van Bragt T, Blankenstein MA. A pilot study of the social correlates of levels of urinary cortisol, prolactin, and testosterone in wild longtailed macaques Macaca fascicularis. Primates. 1991;32:345–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02382675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waser PM. Feeding, ranging and group size in the mangabey Cercocebus albigena. In: Clutton-Brock TH, editor. Primate ecology. London: Academic; 1977. pp. 183–222. [Google Scholar]

- Waser PM. Patterns and consequences of dispersal in gregarious carnivores. In: Gittleman JL, editor. Carnivore behavior, ecology and evolution, Vol. 2. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1996. pp. 267–295. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Rabenold KN. Male-biased dispersal, female philopatry, and routes to fitness in a social corvid. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2005;75:150–159. [Google Scholar]