Abstract

Wnt signaling mediates key developmental and homeostatic processes including stem cell maintenance, growth and cell fate specification, cell polarity and migration. Inappropriate activation of Wnt signaling is linked to a range of human disorders, most notably cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. In the Wnt/β-catenin cascade, signaling events converge on the regulation of ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the crucial transcriptional regulator β-catenin. The emerging mechanisms by which ubiquitin modification of proteins controls cellular pathways comprise both proteolytic and nonproteolytic functions. In nonproteolytic functions, ubiquitin acts as a signaling device in the control of protein activity, subcellular localization and complex formation. Here, we review and discuss recent developments that implicate ubiquitin-mediated mechanisms at multiple steps of Wnt pathway activation.

Key words: Wnt signaling, ubiquitin, β-catenin, dishevelled, signal transduction, protein degradation, cancer, development

Introduction

Wnt signaling pathways co-evolved with the emergence of multicellular organisms to mediate complex cell-cell communication events during development and in adult homeostasis.1,2 Signaling induced by binding of Wnts to their cell surface receptors controls a vast array of cellular processes such as cell proliferation, stem cell maintenance, cell fate decisions, organized cell movements and tissue polarity. Wnts control cell behavior through multiple downstream signaling pathways, including the β-catenin-dependent Wnt cascade and β-catenin-independent planar cell polarity (PCP) and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways.2–7 The Wnt/β-catenin cascade is best characterized and is the primary subject of this review. The key player of this signaling cascade, β-catenin, has a dual function in epithelial cells. It acts in E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesions and instigates Wnt-induced gene programs in the nucleus.1,8 Signaling events in the Wnt/β-catenin cascade revolve around the regulation of the non-membrane-bound pool of β-catenin with potential to act in transcription. Without a Wnt signal, uncomplexed β-catenin in the cytosol is rapidly phosphorylated by a multi-protein complex composed of the scaffolding proteins Axin and Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) and the kinases CK1 and GSKβ. Phospho-β-catenin is immediately recognized and degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Thus, the Axin-APC complex keeps cytosolic levels of β-catenin low. Simultaneous binding of Wnt to Frizzled (Fz) and Lrp5/6 coreceptors leads, via recruitment of the cytoplasmic effector protein Dishevelled (Dvl), to inhibition of the Axin/APC protein complex.2,9 As a consequence the levels of cytoplasmic β-catenin rise, followed by its transport into the nucleus and the activation of target gene transcription by β-catenin/TCF complexes.10

The early recognition of the importance of tight regulation of β-catenin turnover has rendered it a hallmark protein for ubiquitin-proteasome mediated degradation. Inappropriate elevation of β-catenin levels and uncontrolled activation of target genes is linked to a multitude of human disorders, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.1,2

During the last decade, novel regulatory functions of ubiquitin have been uncovered at rapid pace. Ubiquitin modification of proteins displays an unanticipated versatility in the regulation of a variety of cellular processes, including membrane traffic, cell cycle regulation, virus infection, DNA repair and gene transcription.11–13 Here, we review several examples that implicate ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic and nonproteolytic events in the regulation of key Wnt signaling steps at multiple levels of the pathway.

Ubiquitylation is a Highly Versatile Regulator of Protein Stability and Function

Covalent attachment of the small protein ubiquitin to lysine side chains of target proteins is accomplished by a three-step process that involves ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin by an E1 enzyme, conjugation of ubiquitin to an E2 enzyme and E3 enzyme-mediated ligation of ubiquitin to substrate proteins.11,14 The E3 ligases primarily dictate specificity of ubiquitin ligation and, accordingly, are most abundantly present in the human genome (>600 genes) in comparison to the E1 and E2 enzymes, which are encoded by an estimated 2 and 40 genes, respectively.15 Two main classes of E3s have been identified: the HECT-type and RING-type families which differ both structurally and mechanistically in the ubiquitylation of their substrates (reviewed in ref. 16 and 17). The nature of ubiquitin modifications conjugated to substrates is remarkably diverse and the various ubiquitin forms link to distinct cellular pathways and mechanisms. Conjugation with a monomeric ubiquitin can occur at a single lysine residue (monoubiquitylation) or at several lysine residues (multiubiquitylation). Monoubiquitylation is linked to receptor endocytosis, lysosomal targeting, chromatin remodeling and DNA repair.18–21 Modification of proteins with extended ubiquitin chains can occur through sequential conjugation of ubiquitin to a lysine of the preceding ubiquitin (polyubiquitylation).19,22 Each of the seven lysines in Ub (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) can be used in the formation of polyubiquitin chains, creating a range of distinct molecular signals with which proteins can be modified (reviewed in ref. 22). Recently, the formation of linear (head-to-tail) polyubiquitin chains was added to the spectrum of possiblities.23,24 The fate of ubiquitin-modified proteins depends on the type of ubiquitin linkage. K48-linked ubiquitin chains commonly target proteins for proteasome-mediated degradation,11 whereas other ubiquitin linkages mediate both proteolytic as well as non-proteolytic functions.12,13,22 Different functions of the various ubiquitin chains are mediated through selective recognition by ubiquitin-binding domain containing proteins. The large family of ubiquitin-binding domains is remarkably diverse and continues to expand.25 Bringing together ubiquitylated proteins and ubiquitin receptors is an emerging mechanism to bring about specific biological functions, such as the assembly of complex signaling networks.12,13

Ubiquitin modification of proteins is reversible. Disassembly of ubiquitin chains is mediated by deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs). The approximately 90 DUBs encoded in the human genome are categorized in five subclasses: ubiquitin specific proteases (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH), ovarian tumor proteases (OTU) and Josephins, all of which are cysteine proteases, and the JAMM motif family of metallo-proteases (reviewed in ref. 26). As expected from their function, DUBs have been widely implicated in cellular and pathogenic processes that involve ubiquitin-mediated regulation.26–28

Multiple E3 Ligases Target β-catenin for Ubiquitin-mediated Degradation

β-TrCP.

Soon after the discovery of β-catenin in 1987,29 the posttranslational regulation of its stability was placed central to the signaling events in the Wnt pathway.30 Through combined genetic and biochemical approaches, β-catenin levels were recognized to be regulated by CK1- and GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation and subsequent proteolytic degradation.31–38 Target sites for phosphorylation cluster in the flexible N-terminus of β-catenin. CK1 family members (CK1α, -δ and -ε) mediate a priming phosphorylation step at Ser45, followed by GSK3-mediated phosphorylation of Ser33, Ser37 and Thr41.33,39 Insight in the phosphorylation-dependent proteolytic mechanism came from the identification of β-TrCP as the responsible E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes phosphorylated β-catenin40–43 (Fig. 1). β-TrCP is the substrate-binding subunit of a multiprotein Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF) RING-type E3 ligase, and thus directs the ubiquitylation activity of the complex towards substrates.44 β-TrCP binds to a highly conserved consensus substrate recognition motif (DSG(X)2+nS) in β-catenin in a phosphorylation-dependent manner.44–46 The β-TrCP-associated SCF complex subsequently attaches polyubiquitin chains onto nearby lysine residues (Lys-19 and Lys-49) at the N-terminus of β-catenin,45,47 earmarking it for proteasomal degradation. In current models, Wnt stimulation leads to inhibition of GSK3β activity, which prevents β-TrCP-mediated breakdown of β-catenin. As a result, non-phopshorylated β-catenin accumulates, migrates to the nucleus and initiates transcription of target genes.48,49 The importance of CK1- and GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation and β-TrCP recognition in the control of β-catenin stability is further illustrated by the occurrence of β-catenin activating mutations in the N-terminal degron in a wide variety of human cancers.50

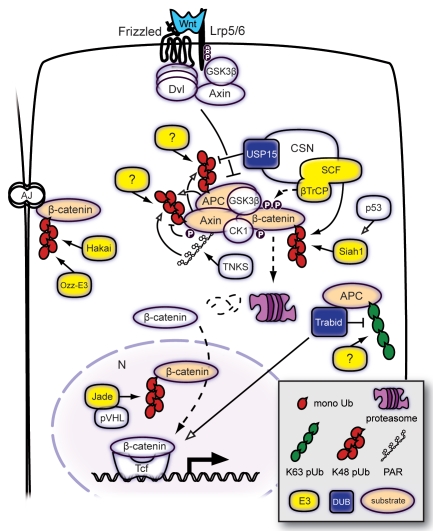

Figure 1.

Ubiquitin-mediated regulation of the core Wnt pathway components APC, Axin and β-catenin. Binding of Wnt to its receptors Frizzled and Lrp5/6 induces recruitment of cytoplasmic proteins including Dvl and Axin. The resulting signaling complex inhibits the constitutive degradation of β-catenin, leading to its translocation to the nucleus (N) and activation of Tcf/Lef target genes. In the absence of Wnt, cytoplasmic β-catenin is phosphorylated by the Axin-APC-GSK3β-CK1 complex. Phospho-β-catenin is subjected to SCFβ-TrCP E3 ligase-mediated polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation. Both Axin and APC can undergo ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and regulate each other's stability. Axin ubiquitylation and degradation is promoted by phosphorylation and poly-ADP-ribosylation (PARsylation). The CSN, which binds and stimulates SCFβ-TrCP activity, includes DUB enzyme Usp15 that protects APC from degradative ubiquitylation. An alternative Wnt-responsive degradation pathway for cytosolic β-catenin is mediated by Jade-1, a ubiquitin ligase that is found primarily in the nucleus and that depends on the tumor suppressor pVHL. Independent of Wnt signaling, cytosolic β-catenin levels are regulated by p53-activated Siah-1 in response to DNA damage. The pool of β-catenin that is associated to adherence junctions (AJ) can also be targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, the involved E3 ligases are Hakai and Ozz-E3. DUB enzyme Trabid is a positive regulator of downstream Wnt-induced transcription and removes K63-linked polyubiquitylation of APC. Filled arrowheads point out enzyme-substrate connection; open arrowheads: positive regulation. Dashed lines indicate protein movement.

Siah-1.

A second pathway for cytosolic β-catenin degradation is induced by genotoxic stress-mediated p53 activation.51,52 Elevated levels of transcriptionally active p53 induce expression of Siah-1, a RING type E3 ligase that interacts with the C-terminus of APC51 and the Arm repeat domains of β-catenin.53 In the absence of p53 activation, Siah-1 levels are extremely low. Siah-1 overexpression in cells decreases the half-life of β-catenin by means of ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation in a β-TrCP-independent manner51 (Fig. 1). Siah-1 can either act together with the E2 enzyme UbcH5a53 or in the context of a unique SCF-like E3 complex (SCFTBL1) comprised of Siah-1, Siah-interacting protein (SIP), Skp1, APC and the β-catenin binding F-box protein Transducin-β-like 1 (TBL1)/Ebi.52 How the general activity and substrate specificity of Siah-1 differs between these two E3 ligase complexes remains unresolved, although in vitro SCFTBL1 activity towards β-catenin was lower than that of Siah-1 alone.53 Unlike β-TrCP, Siah-1 or SCFTBL1 recognize β-catenin in a phosphorylation-independent manner.51,52 As a consequence, Siah-1 also targets mutant forms of β-catenin.51 The lysines in β-catenin modified by Siah-1/UbcH5a (Lys-666 or Lys-671) are located within the binding site of transcriptional co-activators, suggesting that Siah-1 activity directly downregulates transcription of β-catenin target genes.53 Siah-1 selectively conjugates β-catenin with unconventional K11-linked ubiquitin chains, which are known to target for proteasomal degradation.54,55 As Siah-1 targets unmodified β-catenin, the modulation of Siah-1 expression levels by stress conditions such as DNA damage provides a handle to directly control the cytosolic levels of free β-catenin.

Jade-1.

The renal transcriptional co-activator and E3 ligase Jade-1 (gene for apoptosis and differentiation in epithelia) was recently implicated in ubiquitin-mediated downregulation of β-catenin, in a von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein-dependent mechanism.56 VHL itself is a well-characterized E3 ligase subunit and tumor suppressor frequently mutated in renal cancer.57 Jade-1 expression is enriched in kidney tissues, likely through its stabilization by VHL.58 Similar to β-TrCP, Jade-1 directly interacts with the N-terminus of β-catenin in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Consequently, Jade-1 does not target β-catenin in the absence of GSK3β and cannot degrade S33 mutant β-catenin. The characteristics of Jade-1 activity towards β-catenin, however, differ from those of β-TrCP. Combined results from in vitro ubiquitylation and in vivo Xenopus dorsalization assays reveal that Jade-1-mediated control of β-catenin levels extends to both the off- and on-phase of Wnt signaling. Jade-1 acts as a PHD-domain dependent, single-subunit E3 ligase that cooperates with the E2s UbcH6 or UbcH2 to ubiquitylate β-catenin. The predominant localization of Jade-1 to the nucleus suggests that it mainly regulates the nuclear pool of β-catenin (Fig. 1). As Jade-1 stability depends on the presence of a functional VHL protein, a mechanism is suggested by which VHL mutations in renal cell carcinoma lead to Wnt pathway hyperactivation via downregulation of Jade-1. If and how Jade-1 couples to other Wnt pathway components, how its activity is regulated and whether its function extends to extra-renal tissues remains unaddressed.

Ubiquitylation of E-cadherin-bound β-catenin in adherens junctions: Hakai and Ozz-E3.

Besides the regulated turnover of cytosolic and nuclear β-catenin levels, selective ubiquitin-mediated pathways act to target the E-cadherin-bound plasma membrane pool of β-catenin, leading to disassembly of adhesive cell-cell contacts. A c-Cbl-related RING-type E3 ligase, Hakai, binds to and targets E-cadherin and associated β-catenin for ubiquitylation59 (Fig. 1). The ubiquitylated E-cadherin complex is internalized via endocytosis, leading to disruption of cell-cell contacts and enhanced cell motility. Enhanced Hakai activity may therefore participate in epithelial to mesenchymal transitions, in which cells lose their cell adhesion contacts and acquire migratory properties.

In developing striated muscle, a different E3 ligase subunit, Ozz-E3, uses its conserved SOCS box to cooperate with a complex consisting of Elongin B/C, Cullin-5 and Rbx1 in the ubiquitylation of substrate proteins.60 Ozz-E3 binds to and targets β-catenin selectively at the sarcolemma, the muscle cell membrane, for ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation (Fig. 1). The dynamic regulation of β-catenin levels by Ozz-E3 is crucial for normal myofibrillogenesis.60

If and how the activity of these two E3 ligases affects the transcriptional pool of β-catenin is currently unknown.

Regulation of the Regulators: Ubiquitylation of APC and Axin

The negative Wnt pathway regulators Axin and APC cooperate to scaffold a complex which serves to downregulate β-catenin. But how are these regulators regulated? In several studies, treatment of cells with Wnt3a leads to a reduction in Axin and an increase in APC protein levels,61–66 suggesting that their turnover mechanisms are regulated in a Wnt-responsive manner. Indeed, the stability of Axin correlates with its phosphorylation status.61 Specifically, Axin is dephosphorylated after Wnt stimulation, which leads to its enhanced degradation.63,64 The decrease in Axin levels is believed to preclude formation of sufficient Axin-APC complexes, facilitating an increase in transcriptionally active β-catenin.66 The underlying mechanism of Axin degradation awaits further elucidation although a role of APC was proposed.67

In a recent study, homeostatic regulation of Axin levels was shown to occur through a mechanism that involves the binding and activity of poly-ADP-ribosylating enzymes tankyrase 1 and 2.68 Interestingly, poly-ADP-ribose modification (PARsylation) of Axin is linked to its poly-ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation by the proteasome (Fig. 1). If and how binding and activity of tankyrases depends on Wnt signals and what is the responsible E3 ligase is currently unknown.

APC is a reported substrate for ubiquitin-mediated degradation that is facilitated by Axin overexpression.61 Thus, Axin and APC cross-regulate each other's protein levels which may help to control fluctuations in β-catenin levels in cells where expression of one of the binding partners is decreased66 (Fig. 1). The E3 ligase that targets APC for proteasomal degradation remains undiscovered. An interaction of APC with the HECT domain E3 ligase EDD was recently reported,69 but in this case the EDD protein stabilizes APC protein levels and facilitates the downregulation of β-catenin. The elucidation of the interaction mode, type of used ubiquitin linkage and the nature of the substrate involved will be required to understand how EDD modulates APC protein stability.

Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of APC is counterbalanced by the DUB enzyme USP15.70 USP15 is an integral component of the COP9 signalosome (CSN), which commonly regulates the activity of RING-type SCF complex E3s.71 The CSN complex associates with the SCFβ-TrCP E3 complex in a Wnt- and GSK3β-dependent manner. In the resulting supercomplex, CSN enhances SCFβ-TrCP E3 ligase activity whereas the associated USP15 subunit stabilizes APC,70 thus maintaining high levels of Axin-APC complexes (Fig. 1). As a net result, the CSN complex stimulates the degradation of β-catenin. Upon Wnt signaling, the CSN complex would dissociate from SCFβ-TrCP and the APC-Axin complexes, rendering APC susceptible for proteolysis. The enhanced turnover of APC would promote the stabilization of β-catenin. This latter part of the model, however, does not match with other studies that show stabilization of APC upon Wnt treatment.61,62

Dishevelled

Following Wnt binding by Fz and Lrp5/6 receptors at the cell surface, the cytoplasmic effector protein Dishevelled (Dvl) is recruited to bind the Fz receptor C-terminal tail.72–74 In mammals, three Dvl isoforms exist (Dvl1, Dvl2 and Dvl3), with largely overlapping functions.75 Dvl acts as a critical node in the relay of signals from the receptor complex to downstream effectors in β-catenin-dependent pathways to modulate growth and differentiation and in β-catenin-independent pathways, like PCP and convergent extension, to regulate cell motility and polarization.76,77 Accordingly, Dvl is regarded as a decision point for different Wnt-induced downstream signaling branches. Three conserved functional domains are linked to the diverse roles of Dvl in Wnt signaling pathways. The N-terminal DIX domain mediates homo- and heterodimerization events,78,79 the central PDZ domain is involved in binding Fz73,74,80 and, more towards the C-terminus, the DEP domain mediates protein and lipid interactions.81–83 The mechanisms by which Dvl performs its signaling roles remain incompletely understood but involve the regulation of receptor complex clustering,84,85 endocytosis,86,87 stimulation of phosphatidylinositol phosphorylation88 and its direct binding to phospholipids82 (reviewed in ref. 77). Not surprisingly, the levels and (sub)cellular functions of Dvl are tightly regulated via multiple ubiquitin-dependent and tissue-specific pathways.

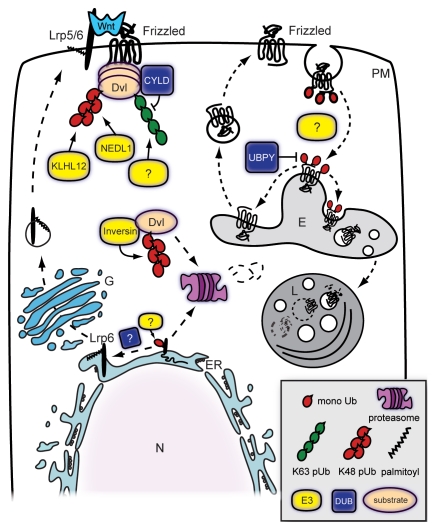

Direct binding of the BTB-protein Kelch-like 12 (KLHL12)-Cullin3 E3 ligase complex to the C-terminus of Dvl is stimulated by Wnt.89 The KLHL12 protein uses its kelch repeat domain to bind Dvl and connects via its BTB domain to Cullin3, thus linking Dvl to the E3 ligase complex. Subsequent ubiquitylation of Dvl leads to its proteasomal degradation (Fig. 2). The Dvl antagonizing role of KLHL12 is confirmed in β-catenin-dependent and -independent Wnt pathways in human cells and zebrafish embryos. Thus, KLHL12 acts as a Wnt-sensitive negative regulator of the Wnt pathway by inducing the degradation of Dvl.

Figure 2.

Ubiquitin in the regulation of upstream Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Upstream of the Axin-APC complex, Wnt signaling is regulated by several ubiquitin-mediated mechanisms. The cell surface levels of the receptors are a balance between biosynthesis and degradation. Monoubiquitylation and palmitolylation regulate Lrp6 exit from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Frizzled monoubiquitylation drives internalization into endosomal compartments (E) and degradation in lysosomes (L). DUB enzyme UBPY was found to inhibit lysosomal degradation of Fz and stimulate its recycling back to the plasma membrane (PM). The Fz-binding protein Dvl is regulated by ubiquitylation in at least two different ways. The E3 ligases KLHL12, NEDL1 and inversin are negative regulators of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by targeting Dvl for K48-linked ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation. Dvl can also be positively regulated by ubiquitylation through K63-linked polyubiquitylation of its DIX domain. Tumor suppressor and DUB enzyme CYLD negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling via inhibition of Dvl ubiquitylation.

In neurons, Dvl was shown to be a substrate for ubiquitylation by the HECT-type E3 ligase NEDL1.90 NEDL1 is predominantly expressed in neuronal tissues and binds to a C-terminal region of Dvl, including the DEP domain and downstream prolinerich repeats. NEDL overexpression enhances the ubiquitylation and degradation of Dvl1 (Fig. 2). Of note, these observations were made with overexpressed proteins and the in vivo role of NEDL1 on Dvl activity by loss-of-function studies has not yet been addressed.

The protein inversin, which links to cystic renal disease upon mutation, inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cells and in vivo (Xenopus) by mediating degradation of the cytoplasmic, but not membrane-bound Dvl,91 (Fig. 2). At the same time, inversin promotes Dvl-mediated functions in noncanonical Wnt signaling, such as during convergent extension movements. Hence, inversin is proposed to act as a molecular switch between different Wnt cascades. Besides binding Dvl, inversin interacts with ANAPC2, a subunit of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), suggesting a role of this multi-subunit E3 ligase in the degradation of Dvl. Indeed, ANAPC2 expression was shown to activate APC/C-dependent degradation of Dvl in a ubiquitin- and proteasome-dependent mechanism and downregulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling in human cells and developing Xenopus.92 ANAPC2-mediated Dvl degradation depends on a classical APC/C recognition motif (RxxL or D-box) that is present in the DEP domain. Loss-of-function studies of inversin and ANAPC2 indicate a close connection between the regulation of Dvl stability and ciliary function of epithelial cells.91,92

A few more studies report on the regulation of Dvl stability by binding partners, but in these cases, the mechanisms remain unclear. The myristoylated form of the vertebrate Naked cuticle homolog NKD2 binds Dvl and mediates its destabilization at the lateral membrane of polarized human epithelial cells.93 The protein Prickle 1, previously implicated in PCP signaling, binds the DEP domain of Dvl3 and mediates its ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation, thereby decreasing β-catenin levels and Wnt-induced transcriptional activity.94 Loss of Prickle in human Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) cells correlates with enhanced levels of Dvl3 and β-catenin stabilization, suggesting clinical relevance of these findings.94

Regulation of Wnt Receptor Traffic by Ubiquitin

Modulation of Fz and Lrp6 receptor expression levels critically influences cellular responses to Wnt.95,96 The mechanisms by which cell surface levels of Wnt receptors are controlled, however, remain poorly understood. Protein synthesis and maturation, endocytosis, lysosomal targeting and degradation commonly regulate the availability of transmembrane receptors at the plasma membrane. In the trafficking of well-characterized membrane-spanning proteins such as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), ubiquitylation plays crucial roles at several decision points along the endosomal system.97 Recently, ubiquitin-mediated mechanisms were identified that regulate Fz and Lrp6 receptor levels at the cell surface.

Proper exit of Lrp6 from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) depends on palmitoylation and tilting of the transmembrane region of the Lrp6 receptor.98 In the absence of palmitoylation and transmembrane tilting, hydrophobic residues are exposed and targeted by a novel ubiquitylation-dependent ER quality control mechanism, in which monoubiquitylation of a nearby lysine earmarks the receptor for ER-retention until folding and modifications like palmitoylation are completed (Fig. 2). In the proposed model, palmitoylation of Lrp6 would lead to its deubiquitylation and subsequent release for transport to the plasma membrane. A Lrp6 lysine mutant that cannot be ubiquitylated escapes ER retention and freely arrives at the cell surface. Thus, ubiquitin attachment regulates Lrp6 exit from the ER. The underlying mechanism holds potential to modulate availability of Lrp6 at the plasma membrane.

Several studies have linked Fz endocytosis to signaling outcome, but the regulatory mechanisms and significance for signaling responses remain unclear.99 Recent work implicates a role of Fz ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation in the cellular responsiveness to Wnt.100 In a screen for involvement of membrane-trafficking regulatory proteins in the formation of wing bristles in Drosophila, the deubiquitylating enzyme UBPY/USP8 was identified as a positive regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. UBPY belongs to the USP family of DUB enzymes and was previously associated with endosomal sorting of receptor tyrosine kinases.101,102 Inactivation of UBPY by mutation or siRNA-mediated knockdown decreases Wnt/β-catenin-dependent gene activation in human cells and Drosophila tissues, whereas a constitutive active UBPY variant enhances both Dvl phosphorylation and β-catenin-mediated reporter activity. Mechanistically, UBPY mediates the deubiquitylation of Fz. As a consequence of UBPY activity, Fz is stabilized by diminished trafficking to lysosomes and enhanced recycling back to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). The effects of UBPY on Fz trafficking were not influenced by Wnt ligand. Thus, UBPY positively regulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by preventing ubiquitylation and lysosomal degradation of Fz, leading to an increase in the available pool of Fz receptors at the cell surface. These findings raise new questions, like which E3 ligase is implicated in Fz ubiquitylation and how both UBPY and E3 ligase activity are controlled. Answers to these questions will help fully understand the regulatory mechanisms by which Fz trafficking is controlled.

Unconventional Polyubiquitin Chains Regulate Wnt Signaling Events

Ubiquitin modification of proteins is an emerging mechanism in a variety of cellular functions that do not involve proteolysis.12,13 Ubiquitin attachment is inducible, reversible and selective ubiquitin chains can be recognized by specific ubiquitin-binding domains, enabling it to act as a signaling device.12 Recently, nonproteolytic roles of K63-linked polyubiquitylation were implicated in key Wnt/β-catenin signaling events.

A general role of K63-linked ubiquitin chain formation in Wnt signaling during hematopoiesis was recently uncovered through the use of conditional Ubc13 knock-out mice.103 Ubc13 is an E2 enzyme that selectively catalyzes K63-linked ubiquitin chain formation when associated with the noncanonical E2 enzyme variants Mms2 and Uev1A. Ubc13 acts in concert with several E3 ligases to target a diverse set of substrates implicated in various cellular processes such as DNA repair, trafficking of membrane-bound proteins and NFκB signaling.13 In a recent study, deletion of Ubc13 was reported to severely impair hematopoiesis, leading to drastic loss of immune cell lineages and thymic and bone marrow atrophy.103 Nine days after depletion of Ubc13, residual populations of cells display accumulation of β-catenin and hyperactivation of Wnt target genes. These findings link Ubc13 function to Wnt signaling in hematopoiesis, although the direct molecular targets and regulatory pathways remain to be identified.

Trabid, a DUB enzyme of the OTU family, was identified as a positive regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in human and Drosophila cells.104 Trabid interacts with the Arm repeat domain of APC to selectively regulate its modification with K63-linked ubiquitin chains. As a consequence, removal of Trabid from cells induces hyperubiquitylation of APC. Epistatic experiments positioned Trabid activity downstream of β-catenin stabilization, suggesting a positive role on β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcriptional events (Fig. 1). Hence, these findings implicate a negative role of K63-linked ubiquitin-modification of APC on Wnt-induced gene transcription. Interestingly, the regulatory role of Trabid on β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription depends on an intact catalytic domain as well as on three N-terminally located tandem Npl4-related zinc finger (NZF) domains that selectively bind ubiquitin chains interlinked through K63. How the regulatory role of Trabid on K63-linked polyubiquitin modification of APC couples to transcriptional activity of β-catenin/TCF-complexes remains unresolved but may involve an earlier described nuclear role of APC in Wnt target gene suppression.105

A positive role of K63-linked ubiquitylation was recently uncovered by the identification of the DUB enzyme and tumor suppressor CYLD as a negative regulator of upstream Wnt/β-catenin signaling.106 Mutations in the CYLD gene cause human cylindromatosis, a tumor syndrome of skin appendages, such as sweat glands and hair follicles.107 Indeed, tumors derived from CYLD-mutant patients display hallmarks of hyperactive Wnt pathway activation, including nuclear β-catenin localization and target gene expression, suggesting that uncontrolled Wnt responses contribute to tumorigenesis in cylindromatosis.106 In human cells, loss of CYLD induces enhanced responsiveness to Wnt through hyperubiquitylation of the upstream Fz-binding effector protein Dishevelled (Dvl). Through the dynamic polymerizing propensity of its N-terminal DIX domain, Dvl is proposed to mediate clustering of Wnt-receptor complexes and facilitate multiple weak and dynamic protein interactions.78 In cells with compromised CYLD activity, at least two lysines in the Dvl DIX domain are modified with K63-linked ubiquitin chains,106 in line with the reported activity of CYLD towards disassembly of K63-ubiquitin linkages.108 Moreover, DIX-domain-mediated polymerization of Dvl is required for ubiquitylation to take place. Together, these findings suggest a model in which the DIX domain of Dvl, upon polymerization of Wnt-bound receptor complexes at the plasma membrane, can be conjugated with K63-linked ubiquitin chains to positively drive stabilization and activation of β-catenin (Fig. 2). Identification of the underlying mechanism by which K63-linked ubiquitin regulates Dvl activity will help to elucidate the still enigmatic role of Dvl in the control of cellular responses to Wnt signaling.

Core Wnt Pathway Proteins Coordinate E3 Ligase Activity

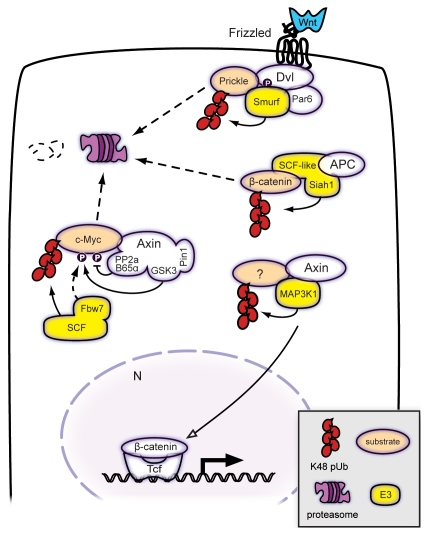

The core Wnt pathway scaffolding proteins Dvl, APC and Axin not only act as targets for ubiquitin modification but can also coordinate E3 ligase ubiquitylation activity towards other substrates. As described above, APC for instance acts independently of Axin as an integrated subunit of the Siah-1-based SCF-like complex to target β-catenin ubiquitylation in conditions of DNA damage (Fig. 3).51

Figure 3.

Wnt signaling components regulate ubiquitylation. Axin acts as a subunit of a larger complex that stimulates SCFFbw7 E3 ligase-mediated degradation of c-Myc. Axin binds and coordinates MAP3K1 E3 ligase activity to drive β-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription. APC acts as a subunit of a SCF-like E3 ligase that includes Siah-1 and destabilizes cytosolic β-catenin upon genotoxic stress. In planar cell polarity signaling, asymmetric Prickle distribution is facilitated by its local ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, through the action of a Fz-Dvl-Par-Smurf complex. Filled arrowheads point out enzyme-substrate; open arrowheads: positive regulation. Dashed lines indicate protein movement.

Axin is reported to promote the ubiquitylation and degradation of the transcriptional activator and oncogene c-Myc in a mechanism independent of APC.109 c-Myc directly binds Axin in a complex with GSK3β, the PP2A-subunit B65α and the prolyl isomerase Pin1. Axin facilitates GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of c-Myc at position T58 and PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of S62. Phospho-T58 c-Myc is subsequently recognized by the SCF(Fbw7) E3 ligase complex that ubiquitylates c-Myc to promote its proteasomal degradation (Fig. 3).110,111 Consequently, loss of Axin leads to stabilization of c-Myc. These findings may bear importance for cancer, as Axin mutations found in several cancer cell lines abrogate the interaction with c-Myc leading to its accumulation and activation of c-Myc-controlled gene programs.

Axin also interacts with the dual kinase and E3 ligase MAP3K1 (MEKK1). The dual activity of MAP3K1 is performed through a C-terminal kinase domain and an N-terminal RING finger-like PHD domain, respectively.112,113 As a kinase, MAP3K1 plays well-characterized roles in the MAP kinase cascade, which converges on c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase (JNK) activation.114 Connected to this role of MAP3K1, Axin is proposed to play a scaffolding role in the regulation of β-catenin-independent Wnt/JNK pathways.112,115,116 Recently, the Axin-MAP3K1 interaction was found to be induced by Wnt and positively drive canonical, Wnt-induced β-catenin-dependent gene transcription.117 Interestingly, the enhanced transcriptional activation does not require kinase activity but rather depends on the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of MAP3K1 (Fig. 3). How ubiquitylation regulates β-catenin/TCF transcription is presently not clear.

Dvl-bound Smurf ubiquitin ligases were recently implicated in the regulation of PCP signaling, which coordinates tissue polarity and cell movements during gastrulation.5,118 Fz-Dvl interactions play a prominent role in the establishment of PCP. Apically colocalized proteins segregate during PCP signaling to form two distinct complexes at opposite sides of the cell. Fz-Dvl-Par6 complexes localize to the distal side, whereas Vang-Prickle complexes localize to the proximal side of the epithelium. Upon its Wnt-induced phosphorylation, Dvl recruits Smurf E3 ligase of the HECT family to the Fz-Dvl-Par6 complex. With help of Par6, Smurf locally targets the Fz PCP antagonistic protein Prickle for ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation. Asymmetric subcellular localization of PCP complexes is thus achieved through localized degradation of PCP components of the opposite complex (Fig. 3). The implications of these findings are exhibited by Smurf1/2−/− mice in which Prickle levels are increased and display loss of asymmetric distribution, leading to PCP defects during convergent extension in gastrulation and in the alignment of sensory cells in the cochlea.118

Conclusion and Perspectives

Ubiquitin has emerged as a key regulatory protein in Wnt pathway activation, controlling (1) the stability of crucial signaling components, (2) receptor maturation, trafficking and lysosomal turnover and (3) protein function through nonproteolytic mechanisms.

Notably, the stability of crucial Wnt signaling components, such as β-catenin and Dvl, is targeted by multiple E3 ligases that are regulated by distinct stimuli, in a tissue-specific manner or within specific subcellular compartments. These findings emphasize the necessity of tight control of β-catenin and Dvl abundance in cells. Aberrant expression or mutations in several of the involved ubiquitin regulatory components link to human disorders, suggesting potential therapeutic relevance of the involved molecular steps.

Nonproteolytic ubiquitin functions are implicated in the regulation of upstream and downstream Wnt signaling steps, but how do the involved ubiquitin forms mediate their role? As shown for NFκB signaling, K63-linked ubiquitin chain-modification of substrates may mediate recruitment of regulatory proteins that recognize both the ubiquitin moiety and the target protein, leading to formation of large, multiprotein signaling platforms and the activation of downstream kinases.12,13 Elucidation of the responsible mechanisms by which K63-linked polyubiquitin chains regulate Wnt signaling steps are expected to lead to new insights in the control of pathway activity.

Core Wnt pathway components not only serve as substrates for ubiquitin-mediated regulation, but can also function to direct or promote E3 ligase activity towards other substrates, as shown for the scaffolding proteins APC, Axin and Dvl. How these proteins switch from prey to predator and how these activities interdepend remains to be determined.

Many challenges lie ahead to address the mechanistic details (attachment sites, chain linkages) by which ubiquitin controls protein function in Wnt signaling and how E3 ligase and DUB activity is controlled in time and space. Among these, the identification of ubiquitin-binding proteins that recognize conjugated ubiquitin moieties and control assembly of complex signaling networks will be of critical importance.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jan P. Gerlach and Ger J.A.M. Strous for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. M.M.M. is supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (UU-2006-3508), University Utrecht (High Potential Grant), European Research Council (ERC-StG no. 242958) and the RUBICON EU network of excellence.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/13204

References

- 1.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohn AD, Moon RT. Wnt and calcium signaling: beta-catenin-independent pathways. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veeman MT, Axelrod JD, Moon RT. A second canon. Functions and mechanisms of beta-catenin-independent Wnt signaling. Dev Cell. 2003;5:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Nathans J. Tissue/planar cell polarity in vertebrates: new insights and new questions. Development. 2007;134:647–658. doi: 10.1242/dev.02772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zallen JA. Planar polarity and tissue morphogenesis. Cell. 2007;129:1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seifert JR, Mlodzik M. Frizzled/PCP signalling: a conserved mechanism regulating cell polarity and directed motility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:126–138. doi: 10.1038/nrg2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brembeck FH, Rosario M, Birchmeier W. Balancing cell adhesion and Wnt signaling, the key role of beta-catenin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng X, Huang H, Tamai K, Zhang X, Harada Y, Yokota C, et al. Initiation of Wnt signaling: control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via frizzled, dishevelled and axin functions. Development. 2008;135:367–375. doi: 10.1242/dev.013540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stadeli R, Hoffmans R, Basler K. Transcription under the control of nuclear Arm/beta-catenin. Curr Biol. 2006;16:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haglund K, Dikic I. Ubiquitylation and cell signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:3353–3359. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ZJ, Sun LJ. Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;33:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickart CM, Eddins MJ. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A, et al. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rotin D, Kumar S. Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:398–409. doi: 10.1038/nrm2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hicke L. Protein regulation by monoubiquitin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:195–201. doi: 10.1038/35056583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haglund K, Di Fiore PP, Dikic I. Distinct monoubiquitin signals in receptor endocytosis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Fiore PP, Polo S, Hofmann K. When ubiquitin meets ubiquitin receptors: a signalling connection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nrm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda F, Dikic I. Atypical ubiquitin chains: new molecular signals. ‘Protein Modifications: Beyond the Usual Suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:536–542. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirisako T, Kamei K, Murata S, Kato M, Fukumoto H, Kanie M, et al. A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J. 2006;25:4877–4887. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwai K, Tokunaga F. Linear polyubiquitination: a new regulator of NFkappaB activation. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:706–713. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ. Ubiquitin-binding domains—from structures to functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reyes-Turcu FE, Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:363–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacco JJ, Coulson JM, Clague MJ, Urbe S. Emerging roles of deubiquitinases in cancer-associated pathways. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:140–157. doi: 10.1002/iub.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wieschaus E, Riggleman R. Autonomous requirements for the segment polarity gene armadillo during Drosophila embryogenesis. Cell. 1987;49:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riggleman B, Schedl P, Wieschaus E. Spatial expression of the Drosophila segment polarity gene armadillo is posttranscriptionally regulated by wingless. Cell. 1990;63:549–560. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90451-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peifer M, Sweeton D, Casey M, Wieschaus E. wingless signal and Zeste-white 3 kinase trigger opposing changes in the intracellular distribution of Armadillo. Development. 1994;120:369–380. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amit S, Hatzubai A, Birman Y, Andersen JS, Ben-Shushan E, Mann M, et al. Axin-mediated CKI phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser 45: a molecular switch for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1066–1076. doi: 10.1101/gad.230302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C, Li Y, Semenov M, Han C, Baeg GH, Tan Y, et al. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell. 2002;108:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3046–3050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters JM, McKay RM, McKay JP, Graff JM. Casein kinase I transduces Wnt signals. Nature. 1999;401:345–350. doi: 10.1038/43830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakanaka C, Leong P, Xu L, Harrison SD, Williams LT. Casein kinase iepsilon in the wnt pathway: regulation of beta-catenin function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12548–12552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Leeuwen F, Samos CH, Nusse R. Biological activity of soluble wingless protein in cultured Drosophila imaginal disc cells. Nature. 1994;368:342–344. doi: 10.1038/368342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanagawa S, Matsuda Y, Lee JS, Matsubayashi H, Sese S, Kadowaki T, et al. Casein kinase I phosphorylates the Armadillo protein and induces its degradation in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2002;21:1733–1742. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yost C, Torres M, Miller JR, Huang E, Kimelman D, Moon RT. The axis-inducing activity, stability and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1443–1454. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang J, Struhl G. Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature. 1998;391:493–496. doi: 10.1038/35154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marikawa Y, Elinson RP. beta-TrCP is a negative regulator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and dorsal axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Mech Dev. 1998;77:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salomon D, Sacco PA, Roy SG, Simcha I, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ, et al. Regulation of beta-catenin levels and localization by overexpression of plakoglobin and inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1325–1335. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuchs SY, Spiegelman VS, Kumar KG. The many faces of beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: reflections in the magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:2028–2036. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu G, Xu G, Schulman BA, Jeffrey PD, Harper JW, Pavletich NP. Structure of a beta-TrCP1-Skp1-beta-catenin complex: destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCF(beta-TrCP1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1445–1456. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13:270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winer IS, Bommer GT, Gonik N, Fearon ER. Lysine residues Lys-19 and Lys-49 of beta-catenin regulate its levels and function in T cell factor transcriptional activation and neoplastic transformation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26181–26187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staal FJ, Noort Mv M, Strous GJ, Clevers HC. Wnt signals are transmitted through N-terminally dephosphorylated beta-catenin. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:63–68. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guger KA, Gumbiner BM. A mode of regulation of beta-catenin signaling activity in Xenopus embryos independent of its levels. Dev Biol. 2000;223:441–448. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polakis P. The oncogenic activation of beta-catenin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Stevens J, Rote CA, Yost HJ, Hu Y, Neufeld KL, et al. Siah-1 mediates a novel beta-catenin degradation pathway linking p53 to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Mol Cell. 2001;7:927–936. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuzawa SI, Reed JC. Siah-1, SIP and Ebi collaborate in a novel pathway for beta-catenin degradation linked to p53 responses. Mol Cell. 2001;7:915–926. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimitrova YN, Li J, Lee YT, Rios-Esteves J, Friedman DB, Choi HJ, et al. Direct ubiquitination of beta-catenin by Siah-1 and regulation by the exchange factor TBL1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13507–13516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin L, Williamson A, Banerjee S, Philipp I, Rape M. Mechanism of ubiquitin-chain formation by the human anaphase-promoting complex. Cell. 2008;133:653–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu P, Duong DM, Seyfried NT, Cheng D, Xie Y, Robert J, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell. 2009;137:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chitalia VC, Foy RL, Bachschmid MM, Zeng L, Panchenko MV, Zhou MI, et al. Jade-1 inhibits Wnt signalling by ubiquitylating beta-catenin and mediates Wnt pathway inhibition by pVHL. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ncb1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaelin WG., Jr The von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:865–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou MI, Wang H, Ross JJ, Kuzmin I, Xu C, Cohen HT. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor stabilizes novel plant homeodomain protein Jade-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39887–39898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujita Y, Krause G, Scheffner M, Zechner D, Leddy HE, Behrens J, et al. Hakai, a c-Cbl-like protein, ubiquitinates and induces endocytosis of the E-cadherin complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:222–231. doi: 10.1038/ncb758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nastasi T, Bongiovanni A, Campos Y, Mann L, Toy JN, Bostrom J, et al. Ozz-E3, a muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase, regulates beta-catenin degradation during myogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;6:269–282. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi J, Park SY, Costantini F, Jho EH, Joo CK. Adenomatous polyposis coli is downregulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in a process facilitated by Axin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49188–49198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papkoff J, Rubinfeld B, Schryver B, Polakis P. Wnt-1 regulates free pools of catenins and stabilizes APC-catenin complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2128–2134. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto H, Kishida S, Kishida M, Ikeda S, Takada S, Kikuchi A. Phosphorylation of axin, a Wnt signal negative regulator, by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates its stability. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10681–10684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willert K, Shibamoto S, Nusse R. Wnt-induced dephosphorylation of axin releases beta-catenin from the axin complex. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1768–1773. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.14.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tolwinski NS, Wehrli M, Rives A, Erdeniz N, DiNardo S, Wieschaus E. Wg/Wnt signal can be transmitted through arrow/LRP5,6 and Axin independently of Zw3/Gsk3beta activity. Dev Cell. 2003;4:407–418. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee E, Salic A, Kruger R, Heinrich R, Kirschner MW. The roles of APC and Axin derived from experimental and theoretical analysis of the Wnt pathway. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takacs CM, Baird JR, Hughes EG, Kent SS, Benchabane H, Paik R, et al. Dual positive and negative regulation of wingless signaling by adenomatous polyposis coli. Science. 2008;319:333–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1151232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang SM, Mishina YM, Liu S, Cheung A, Stegmeier F, Michaud GA, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohshima R, Ohta T, Wu W, Koike A, Iwatani T, Henderson M, et al. Putative tumor suppressor EDD interacts with and upregulates APC. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1339–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang X, Langelotz C, Hetfeld-Pechoc BK, Schwenk W, Dubiel W. The COP9 signalosome mediates beta-catenin degradation by deneddylation and blocks adenomatous polyposis coli destruction via USP15. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:691–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang-Snyder J, Miller JR, Brown JD, Lai CJ, Moon RT. A frizzled homolog functions in a vertebrate Wnt signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1302–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70716-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Umbhauer M, Djiane A, Goisset C, Penzo-Mendez A, Riou JF, Boucaut JC, et al. The C-terminal cytoplasmic Lys-thr-X-X-X-Trp motif in frizzled receptors mediates Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. EMBO J. 2000;19:4944–4954. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.18.4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong HC, Bourdelas A, Krauss A, Lee HJ, Shao Y, Wu D, et al. Direct binding of the PDZ domain of Dishevelled to a conserved internal sequence in the C-terminal region of Frizzled. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1251–1260. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00427-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee YN, Gao Y, Wang HY. Differential mediation of the Wnt canonical pathway by mammalian Dishevelleds-1, -2 and -3. Cell Signal. 2008;20:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wharton KA., Jr Runnin' with the Dvl: proteins that associate with Dsh/Dvl and their significance to Wnt signal transduction. Dev Biol. 2003;253:1–17. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao C, Chen YG. Dishevelled: The hub of Wnt signaling. Cell Signal. 2009;22:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schwarz-Romond T, Fiedler M, Shibata N, Butler PJ, Kikuchi A, Higuchi Y, et al. The DIX domain of Dishevelled confers Wnt signaling by dynamic polymerization. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rothbacher U, Laurent MN, Deardorff MA, Klein PS, Cho KW, Fraser SE. Dishevelled phosphorylation, subcellular localization and multimerization regulate its role in early embryogenesis. EMBO J. 2000;19:1010–1022. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Semenov MV, Snyder M. Human dishevelled genes constitute a DHR-containing multigene family. Genomics. 1997;42:302–310. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wong HC, Mao J, Nguyen JT, Srinivas S, Zhang W, Liu B, et al. Structural basis of the recognition of the dishevelled DEP domain in the Wnt signaling pathway. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/82047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simons M, Gault WJ, Gotthardt D, Rohatgi R, Klein TJ, Shao Y, et al. Electrochemical cues regulate assembly of the Frizzled/Dishevelled complex at the plasma membrane during planar epithelial polarization. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:286–294. doi: 10.1038/ncb1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Axelrod JD, Miller JR, Shulman JM, Moon RT, Perrimon N. Differential recruitment of Dishevelled provides signaling specificity in the planar cell polarity and Wingless signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2610–2622. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bilic J, Huang YL, Davidson G, Zimmermann T, Cruciat CM, Bienz M, Niehrs C. Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science. 2007;316:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1137065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Metcalfe C, Mendoza-Topaz C, Mieszczanek J, Bienz M. Stability elements in the LRP6 cytoplasmic tail confer efficient signalling upon DIX-dependent polymerization. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1588–1599. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen W, ten Berge D, Brown J, Ahn S, Hu LA, Miller WE, et al. Dishevelled 2 recruits beta-arrestin 2 to mediate Wnt5A-stimulated endocytosis of Frizzled 4. Science. 2003;301:1391–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1082808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu A, Rual JF, Tamai K, Harada Y, Vidal M, He X, Kirchhausen T. Association of Dishevelled with the clathrin AP-2 adaptor is required for Frizzled endocytosis and planar cell polarity signaling. Dev Cell. 2007;12:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pan W, Choi SC, Wang H, Qin Y, Volpicelli-Daley L, Swan L, et al. Wnt3a-mediated formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates LRP6 phosphorylation. Science. 2008;321:1350–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1160741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Angers S, Thorpe CJ, Biechele TL, Goldenberg SJ, Zheng N, MacCoss MJ, et al. The KLHL12-Cullin-3 ubiquitin ligase negatively regulates the Wnt-beta-catenin pathway by targeting Dishevelled for degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:348–357. doi: 10.1038/ncb1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miyazaki K, Fujita T, Ozaki T, Kato C, Kurose Y, Sakamoto M, et al. NEDL1, a novel ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase for dishevelled-1, targets mutant superoxide dismutase-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11327–11335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Kronig C, et al. Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2005;37:537–543. doi: 10.1038/ng1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ganner A, Lienkamp S, Schafer T, Romaker D, Wegierski T, Park TJ, et al. Regulation of ciliary polarity by the APC/C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17799–17804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909465106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hu T, Li C, Cao Z, Van Raay TJ, Smith JG, Willert K, et al. Myristoylated naked2 antagonizes WNT-{beta}-catenin activity by degrading dishevelled-1 at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13561–13568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chan DW, Chan CY, Yam JW, Ching YP, Ng IO. Prickle-1 negatively regulates Wnt/beta-catenin pathway by promoting Dishevelled ubiquitination/degradation in liver cancer. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1218–1227. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cadigan KM, Fish MP, Rulifson EJ, Nusse R. Wingless repression of Drosophila frizzled 2 expression shapes the Wingless morphogen gradient in the wing. Cell. 1998;93:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang J, Li Y, Liu Q, Lu W, Bu G. Wnt signaling activation and mammary gland hyperplasia in MMTV-LRP6 transgenic mice: implication for breast cancer tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29:539–549. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Acconcia F, Sigismund S, Polo S. Ubiquitin in trafficking: the network at work. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1610–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Abrami L, Kunz B, Iacovache I, van der Goot FG. Palmitoylation and ubiquitination regulate exit of the Wnt signaling protein LRP6 from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5384–5389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710389105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gagliardi M, Piddini E, Vincent JP. Endocytosis: a positive or a negative influence on Wnt signalling? Traffic. 2008;9:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mukai A, Yamamoto-Hino M, Awano W, Watanabe W, Komada M, Goto S. Balanced ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation of Frizzled regulate cellular responsiveness to Wg/Wnt. EMBO J. 2010;29:2114–2125. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mizuno E, Iura T, Mukai A, Yoshimori T, Kitamura N, Komada M. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor downregulation by UBPY-mediated deubiquitination at endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5163–5174. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Row PE, Prior IA, McCullough J, Clague MJ, Urbe S. The ubiquitin isopeptidase UBPY regulates endosomal ubiquitin dynamics and is essential for receptor downregulation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12618–12624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wu X, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Sun SC. Regulation of hematopoiesis by the K63-specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906547106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tran H, Hamada F, Schwarz-Romond T, Bienz M. Trabid, a new positive regulator of Wnt-induced transcription with preference for binding and cleaving K63-linked ubiquitin chains. Genes Dev. 2008;22:528–542. doi: 10.1101/gad.463208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA. The APC tumor suppressor counteracts beta-catenin activation and H3K4 methylation at Wnt target genes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:586–600. doi: 10.1101/gad.1385806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tauriello DV, Haegebarth A, Kuper I, Edelmann MJ, Henraat M, Canninga-van Dijk MR, et al. Loss of the tumor suppressor CYLD enhances Wnt/beta-catenin signaling through K63-linked ubiquitination of Dvl. Mol Cell. 2010;37:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, Takahashi M, Rapley E, Barfoot R, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160–165. doi: 10.1038/76006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Komander D, Lord CJ, Scheel H, Swift S, Hofmann K, Ashworth A, et al. The structure of the CYLD USP domain explains its specificity for Lys63-linked polyubiquitin and reveals a B box module. Mol Cell. 2008;29:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Arnold HK, Zhang X, Daniel CJ, Tibbitts D, Escamilla-Powers J, Farrell A, et al. The Axin1 scaffold protein promotes formation of a degradation complex for c-Myc. EMBO J. 2009;28:500–512. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, Grim JE, Harper JW, Eisenman RN, et al. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Kamura T, Nishiyama M, Tsunematsu R, Imaki H, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;23:2116–2125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang Y, Neo SY, Wang X, Han J, Lin SC. Axin forms a complex with MEKK1 and activates c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase through domains distinct from Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35247–35254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lu Z, Xu S, Joazeiro C, Cobb MH, Hunter T. The PHD domain of MEKK1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of ERK1/2. Mol Cell. 2002;9:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Weston CR, Davis RJ. The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang Y, Qiu WJ, Liu DX, Neo SY, He X, Lin SC. Differential molecular assemblies underlie the dual function of Axin in modulating the WNT and JNK pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32152–32159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Luo W, Ng WW, Jin LH, Ye Z, Han J, Lin SC. Axin utilizes distinct regions for competitive MEKK1 and MEKK4 binding and JNK activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37451–37458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sue Ng S, Mahmoudi T, Li VS, Hatzis P, Boersema PJ, Mohammed S, et al. MAP3K1 functionally interacts with Axin1 in the canonical Wnt signalling pathway. Biol Chem. 2010;391:171–180. doi: 10.1515/bc.2010.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Narimatsu M, Bose R, Pye M, Zhang L, Miller B, Ching P, et al. Regulation of planar cell polarity by Smurf ubiquitin ligases. Cell. 2009;137:295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yada M, Hatakeyama S, Kamura T, Nishiyama M, Tsunematsu R, Imaki H, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;23:2116–2125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]