Abstract

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is a disease characterized by dysregulated cell proliferation associated with impaired cell differentiation, and current treatment regimens rarely save the patient. Thus, new mechanism-based approaches are needed to improve prognosis of this disease. We have investigated in preclinical studies the potential anti-leukemia use of the plant-derived polyphenol Silibinin (SIL) in combination with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25D). Although most of the leukemic blasts ex vivo responded by differentiation to treatment with this combination, the reasons for the absence of SIL-1,25D synergy in some cases were unclear. Here we report that failure of SIL to enhance the action of 1,25D is likely due to the SIL-induced increase in the activity of differentiation-antagonizing cell components, such as ERK5. This kinase is under the control of Cot1/Tlp2, and inhibition of Cot1 activity by a specific pharmacological inhibitor 4-(3-chloro-4-fluorophenylamino)-6-(pyridin-3-yl-methylamino-3-cyano-[1-7]-naphthyridine), or by Cot1 siRNA, increases the differentiation by SIL/1,25D combinations. Conversely, overexpression of a Cot1 construct increases the cellular levels of P-ERK5, and SIL/1,25D-induced differentiation and cell cycle arrest are diminished. It appears that reduction in ERK5 activity by inhibition of Cot1 allows SIL to augment the expression of 1,25D-induced differentiation promoting factors and cell cycle regulators such as p27Kip1, which leads to cell cycle arrest. This study shows that in some cell contexts SIL/1,25D can promote expression of both differentiation-promoting and differentiation-inhibiting genes, and that the latter can be neutralized by a highly specific pharmacological inhibitor, suggesting a potential for supplementing treatment of AML with this combination of agents.

Key words: plant antioxidants, silibinin, vitamin D, Cot1 oncogene, MAPK signaling, ERK5, p27Kip1

Introduction

Botanical health remedies have an established role in Oriental traditional medicine, but their acceptance into western medical practice has been in most cases controversial. In particular, the role of anti-oxidants in human health has recently been questioned.1–4 The plant-derived compounds in widespread use, such as digitalis, the vinca alkaloids and taxane derivatives, have been purified and their mechanisms of action to a large extent elucidated. Since it can be argued that an understanding how such compounds can exert their action will help to gain their acceptance into clinical trials, we have focused on the mechanisms of action of the plant-derived polyphenol Silibinin (SIL). This flavonolignan has been isolated from milk thistle Silybum marianum, and has an established efficacy as a hepatoprotective agent,5–9 and has promising activities against many types of human malignant tumors.10–12 Studies in our laboratories focus on the action of SIL as an enhancer of the activity of 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25D) on the induction of differentiation and inhibition of the proliferation of human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells in vitro and ex vivo.13–17

Although 1,25D is an effective inducer of differentiation and inhibits the proliferation of AML cells in vitro, the concentrations required to achieve it made it impossible to achieve clinically acceptable results in early phase clinical trials.18–20 One of the current approaches to overcome this difficulty is to combine 1,25D with enhancers,21 but the mechanisms of such synergies are hard to unravel. In our previous studies, we determined the role of MAPK pathways in the signaling of 1,25D-induced differentiation,22–24 and using a similar strategy we examined an important facet of SIL-1,25D interaction, the ability of SIL to cooperate with 1,25D in a cell type specific manner. To accomplish this we used cell lines arrested at different stages of maturity and AML blasts in primary culture. The results indicate that inhibition of ERK5 activity by Cot1 knock down removes a barrier to SIL-1,25D cooperation.

Results

Cot1 enzyme activity increases in AML cells during 1,25D-induced differentiation.

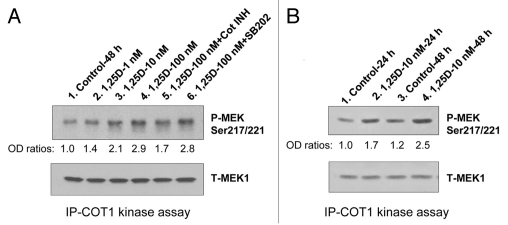

Apart from the well established Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK cascade, the upstream regulators of the different branches of MAPK pathways are poorly understood, and there is increasing evidence that the regulation of MAPK pathways is cell- and external stimulus-specific. In particular, Cot1 has been reported to have pleiotrophic control over several MAPK pathways,25–29 though it is not clear if each pathway is regulated by Cot1 in every cell type. In human AML cells we found that Cot1 can influence the Raf pathway through downregulation of KSR1 and KSR2,30 the platforms for Raf interactions,31–33 and we provided evidence consistent with the reported control by Cot1 of c-jun pathway in other cell types.26,27,34 In order to further examine the mechanisms of these pleiotrophic actions of Cot1, it is necessary to establish that it is the enzymatic activity of Cot1 that is increasing in differentiating AML cells. Using an in vitro kinase assay of Cot1 immunoprecipitated from 1,25D-treated HL60 cells, we demonstrated that Cot1 kinase activity increases in 1,25D concentration-(Fig. 1A), and time- (Fig. 1B) dependent manner. We also confirmed the specificity of the Cot1 inhibitor (Cot INH), by its inhibition of the kinase reaction when added to the cell-free reaction mix, whereas SB 202900, an inhibitor of p38 MAPK, had no effect, as expected (Fig. 1A). This shows that 1,25D-induced Cot1 can function in AML cells as a kinase, and is thus capable of activating the known MAPK cascades.

Figure 1.

Cot1 kinase activity increases in differentiating HL60 cells in 1,25D concentration- and time-dependent manner. HL60 cells were exposed to 1 nM, 10 nM and 100 nM 1,25D for 48 h (A), or to 1 nM 1,25D for 24 h and 48 h. (B) Cells were lysed and kinase activity of immunoprecipitated Cot1 was measured using human recombinant MEK1 (1 µg) as the substrate. The Cot1 inhibitor (5 µM) and SB202190, p38MAPK inhibitor (10 µM), were used as the positive and negative controls in the kinase reaction mix, respectively. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, and the levels of MEK1 phosphorylated at Ser217/221 and total MEK were determined by western blotting. The total MEK levels served to verify equal amounts of substrate in each reaction mix. A representative of four similar experiments is shown.

Cot INH increases SIL and 1,25D-induced dif ferentiation and growth arrest in primitive AML KG-1a cells.

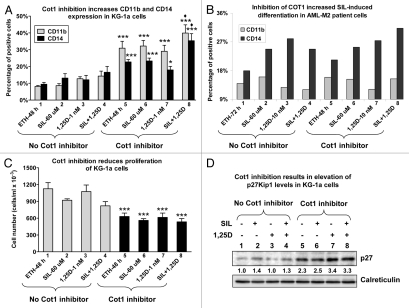

KG-1a cells are arrested very early in the myeloid differentiation lineage, and do not respond to various differentiating agents,35,36 including high concentrations of 1,25D or its derivatives when added alone,37,38 so we tested if the addition of SIL and Cot INH would overcome this block, a matter of potential clinical importance for treatment of AML. Although 1,25D or SIL alone had no appreciable effect on differentiation of these cells, the addition of Cot INH alone resulted in a marked increase in the expression levels of both CD11b and CD14 cell surface myeloid markers (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the addition of Cot INH caused a significant enhancement of the differentiation effect of the SIL/1,25D combination which induced only weak differentiation in the absence of the inhibitor (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, treatment of KG-1a cells with Cot INH, either alone or in the presence of SIL and/or 1,25D, produced a marked inhibition of cell proliferation (Fig. 2C), without a significant decrease in cell viability (data not shown). Consistent with these findings, Cot INH markedly increased the levels of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of Cot1 kinase activity enhances differentiation of primitive AML KG-1a cells and of blasts from a patient with AML, and inhibits proliferation of KG-1a cells concomitant with elevation of p27Kip1 levels. KG-1a cells (A, C and D) or AML blasts FAB subtype M2 (46, XX; +21, del 7, FLT-3 wild type, Nucleophosmin wild type) (B) were preincubated without or with 5 µM Cot1 inhibitor (INH) for 1 h followed by treatment with 1 nM 1,25D, 60 µM SIL or both for an additional 48 h (KG-1a) or 72 h (blasts). The expression of monocytic differentiation markers CD11b and CD14 (A and B) was determined by flow cytometry, and viable cell numbers (C) by counting trypan blue excluding cells. Proteins from KG-1a whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting, and relative p27 protein levels (indicated beneath the blot) were determined by densitometry. Calreticulin was used as the protein loading control. Asterisk *indicates, p < 0.05 and ***p > 0.001 vs. corresponding samples treated in the absence of Cot1 INH (n = 4).

Cot INH also increased differentiation of SIL/1,25D-treated AML (FAB subtype M2) patient's cells ex vivo (Fig. 2B) though there was insufficient material to perform cell proliferation studies. This patient had chromosome 7 deletion, a feature associated with sensitivity to 1,25D,39 and interestingly, Cot INH reversed the SIL inhibition of 1,25D-induced differentiation (compare group 4 with group 8 in Fig. 2B). Taken together, our results suggest that the addition of Cot INH to SIL/1,25D combinations may be of value for induction of differentiation of 1,25D-resistant AML cells, and that at least one major function of Cot1 is to promote cell proliferation, consistent with its role as an oncogene.40–41

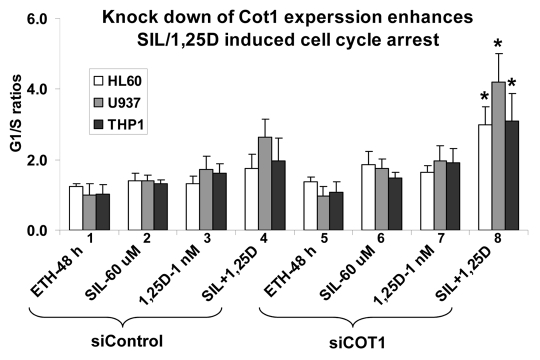

Knockdown of Cot1 by siRNA enhances G1 arrest in SIL/1,25D-treated AML cells.

To further validate the mechanistic aspects of this study we manipulated Cot1 expression to determine its effects on differentiation and growth arrest of AML cells at different maturation levels—HL60 cells with moderate maturation arrest (FAB classification M2), and more mature U937 (M4) and THP-1 (M5) cells.42 All cell types examined showed an enhancement of SIL and 1,25D-induced G1 arrest when these compounds were combined (Fig. 3, group 4), and the inhibition of the cell cycle progression was markedly increased by Cot1 siRNA (siCot1) transfection (Fig. 3, group 8).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of Cot1 expression by Cot1 siRNA enhances SIL/1,25D-induced G1 cell cycle arrest in AML cells. HL60, U937 and THP1 cells were transfected with Cot1 siRNA (siCot1) or scrambled control siRNA (siControl) oligonucleotides. Following 48 h, the cells were exposed to the indicated agents for an additional 48h. Cell cycle distribution was determined by flow cytometry of propidium iodide (PI)-stained cells, and the G1 to S phase ratios were calculated to asses the G1 block. Asterisk *indicates, p < 0.05 for the comparison of cells transfected with siCot1 RNA and exposed to SIL/1,25D vs. corresponding SIL/1,25D samples transfected with siControl RNA (n = 3).

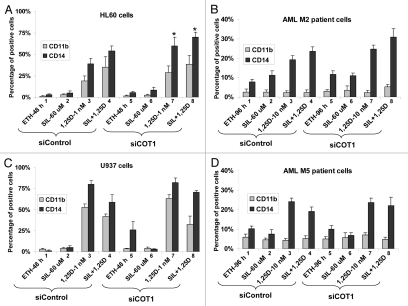

siCot1 enhances SIL/1,25D-induced monocytic differentiation in established and primary cultures of AML cells.

While SIL potentiates the differentiating effect of 1,25D in some cell lines and many primary AML cell cultures, this is not invariable, as exemplified in Figures 2 and 4. In the cell lines studied here the more primitive cell lines, KG-1a and HL60, exhibited to varying extent, potentiation of 1,25D effect (Figs. 2A and 4A), while U937 and THP-1 cells did not (Fig. 4C and data not shown). The cell context-dependent enhancement of the differentiating effect of 1,25D by SIL was also noted in patient blasts in primary culture, with M2 blasts being more responsive to the 1,25D/SIL combination in the presence of siCot (Fig. 4B) than the M5 blasts (Fig. 4D), though we had insufficient samples to make a firm generalization. We then proceeded to examine if we can identify molecular basis for these differences.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of Cot1 expression by siCot1 enhances SIL- and 1,25D-induced monocytic differentiation. (A) HL60 cells, (B) blasts isolated from peripheral blood of a patient with AML subtype M2 (46, XX; del11q24), MLL-1 mutation), (C) U937 cells and (D) AML blasts subtype M5a (46, XX; Trisomy 21, FLT-3 mutation with increased internal tandems repeats), were transfected with siCot1 or siControl RNA. Following 48 h, the cells were exposed to the indicated agents for an additional 48 h. CD11b and CD14 expression was determined by flow cytometry. Asterisk *indicates, p < 0.05 for the comparison of cells transfected with siCot1 RNA and exposed to 1,25D and SIL/1,25D vs. corresponding samples transfected with siControl RNA (n = 3).

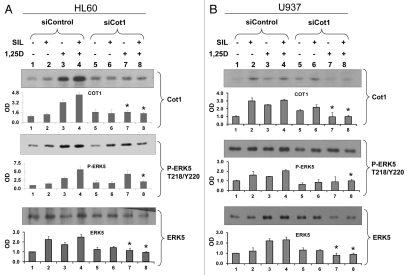

SIL and 1,25D enhance cellular ERK5 and P-ERK5 levels and SIL/1,25D combination further increases these levels, but siCot1 abrogates the SIL/1,25D-induced increase in a cell type-dependent manner.

It was established in several cellular systems that Cot1 regulates phosphorylation of MEK5, which in turn phosphorylates ERK5, a growth-promoting kinase.27 SIL and 1,25D-induced increases in Cot1 expression and activity (Figs. 1 and 5) were therefore transmitted to ERK5 activation in HL60, U937 and THP-1 cells (Fig. 5 and data not shown). ERK5 phosphorylation was accompanied by increased ERK5 levels, perhaps by stabilizing phosphorylations. Interestingly, in HL60 cells the effects of SIL and 1,25D on P-ERK5 levels were approximately additive, yet when Cot1 levels were reduced by siCot1, SIL reduced the 1,25D-induced increase in P-ERK5 and ERK5 (Fig. 5A, compare groups 7 and 8). In contrast, in U937 cells in which Cot1 levels were knocked-down by siCot1, SIL did not reduce 1,25D-induced P-ERK5 and ERK5 levels (Fig. 5B, compare groups 7 and 8). This raises the possibility that the lack of reduction of the 1,25D-induced P-ERK5 levels in the U937 cell context reduces the ability of SIL to enhance 1,25D-induced differentiation (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that by abrogating the increases in ERK5 and P-ERK5 levels in SIL/1,25D-treated cells, siCot1 enhances differentiation even in cell types in which SIL does not enhance differentiation (e.g., Fig. 2B).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of Cot1 expression by siCot1 abrogates SIL/1,25D-induced increase in P-ERK5 and ERK5 expression in a cell type-dependent manner. (A) HL60 cells and (B) U937 cells were transfected with siCot1 or siControl RNA. Following 48 h, cells were exposed to the indicated agents for an additional 48 h. The whole cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to western blot analysis and relative P-ERK5 and ERK5 levels were determined by densitometry. The bar graph below each representative blot shows mean OD values ± SD of three experiments. Since there was some minor variability between the blots, the individual signals shown on the blots are not always representative of the mean. Note that the difference between lanes 7 and 8 was only apparent in HL60 cells. Asterisk * indicates, p < 0.05 for the comparison of cells transfected with siCot1 RNA and exposed to 1,25D and SIL/1,25D vs. corresponding samples transfected with siControl RNA (n = 3).

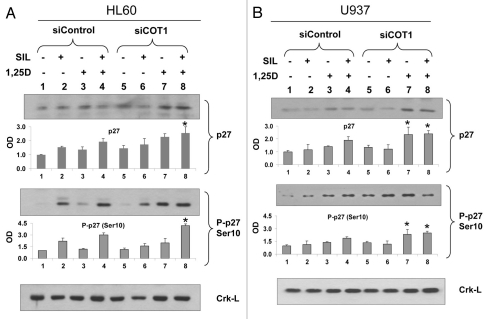

SIL increases p27Kip1 and P-p27Kip1(Ser10) levels, and combination with 1,25D and siCot1 produces their highest level in HL60, but not in U937 cells.

To determine a candidate effector of SIL/1,25D-induced cell cycle block, we examined the levels and phosphorylation of p27Kip1, an essential component of cell cycle control43 known to be regulated in differentiating AML cells,44 and reported to be negatively regulated by ERK5 in human macrophages.45 We found that in HL60 cells, in which SIL enhances the differentiating effect of 1,25D (Fig. 4A), SIL increases the stabilizing phosphorylation of p27Kip1 on serine 10 (Ser10) and enhances the effect of the low concentration (1 nM) of 1,25D on these levels (Fig. 6A). In contrast, in U937 cells SIL has only a modest effect on P-p27Kip1(Ser10) levels, or on the enhancement of 1,25D-induced p27Kip1 expression and this is more apparent after knock-down of Cot1, where SIL does not increase the 1,25D-induced p27Kip1 levels (Fig. 6B, compare groups 7 and 8). This lack of enhancement of p27Kip1 levels correlates with the lack of SIL enhancement of differentiation in U937 cells (Fig. 4C), which however may be abrogated by inhibition of Cot1 activity, at least in AML blasts (Fig. 2B). We have not noted a significant effect of siCot1 on the Thr187 phosphorylation of p27Kip1, which reduces p27Kip1 stability, or on p21Waf1 levels (data not shown). Thus, these data suggest that p27Kip1 may be a major regulator of cell cycle arrest in SIL/1,25D-treated cells, and its upregulation by the inhibition of Cot1-ERK5 axis may contribute to monocytic differentiation in a cell-type dependent manner.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of Cot1 expression by siCot1 oligonucleotides enhances the SIL/1,25D-induced increase in P-p27Kip1(Ser10) and p27Kip1 expression in a cell type-dependent manner. (A) HL60 cells and (B) U937 cells were transfected with siCot1 or siControl RNA. Following 48 h, cells were exposed to the indicated agents for an additional 48 h. The whole cell lysates were then prepared and subjected to western blot analysis and relative P-p27 (Ser10) and p27Kip1 protein levels were determined by densitometry. The bar graph below each representative blot shows mean OD values ± SD of three experiments. Since there was some minor variability between the blots, the individual signals shown on the blots are not always representative of the mean. Asterisk * indicates, p < 0.05 for the comparison of cells transfected with siCot1 RNA and exposed to 1,25D and SIL/1,25D vs. corresponding samples transfected with siControl RNA (n = 3). Note that the difference between lanes 7 and 8 was only apparent in HL60 cells.

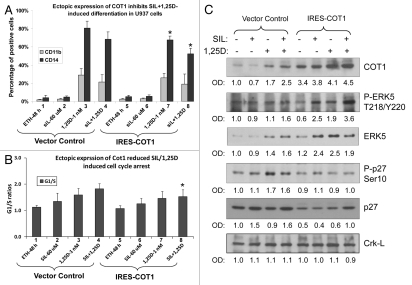

Overexpression of Cot1 diminishes SIL/1,25D-induced differentiation, cell cycle arrest and p27Kip1(Ser10) phosphorylation concomitant with increased P-ERK5 cellular levels.

To further validate the results obtained with Cot1 knock down by siCot1, we overexpressed the IRES-Cot1 construct, and obtained stable clones in U937 cells which maintained their viability better than the other AML cell lines during the procedures required for these experiments, such as cell sorting for the transfection marker. As shown in Figure 7, overexpression of Cot1 had inhibitory effects on cell differentiation and the associated cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase, with most changes apparent in the SIL/1,25D group (Fig. 7B, lane 8). The reduction in cell differentiation and cell cycle arrest was accompanied by reduced P-p27Kip1(Ser10) levels (compare lane 4 with lane 8 in Fig. 7C). In contrast, P-ERK5 levels increased in parallel with Cot1 levels, consistent with ERK5 being downstream from Cot1 in the MAPK cascade, but a negative upstream regulator of p27Kip1(Ser10) phosphorylation. Transfection of IRES-Cot1 kinase-inactive Cot1 mutant did not have the above effects (data not shown), further supporting the role of Cot1 enzyme activity in the cascade of events that lead to reduced p27Kip1(Ser10) phosphorylation.

Figure 7.

Ectopic expression of Cot1 reduces SIL/1,25D-induced differentiation, cell cycle arrest and p27Kip1 phosphorylation concomitant with increased P-ERK5 cellular levels. U937 cells were transfected with either empty vector (Vector Control) or IRES-Cot1 construct, then sorted by flow cytometry (FC) using GFP marker to initiate selection of stable transfectants, as detailed in Materials and Methods. The transfected cells were treated with the indicated compounds for 48 h. (A) CD11b and CD14 markers and (B) cell cycle arrest, as demonstrated by the ratios of cells in the G1 to S phase compartments determined by FC. (C) Whole cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for the indicated proteins. The optical density signals of each protein are shown under each blot, relative to the loading control (Crk-L). Note that the clone selection procedure resulted in slightly altered protein levels in the IRES-Vector Control treated cells, as compared to siControl treated cells in Figure 5B. The asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05 for the comparison of cells transfected with IRES-Cot1 vs. corresponding samples transfected with Vector Control (n = 3).

Discussion

The major finding in this report is the identification of two opposing effects on induction of differentiation of AML cells by SIL/1,25D. One, the upregulation of p27Kip1 is not unexpected, since this cell cycle regulator, as well as p21Waf1, has already been reported to be essential for SIL-induced cell cycle arrest in prostate carcinoma cells,46 while upregulation of p27Kip1 by 1,25D is well known.44,47,48 However, the concurrent SIL and 1,25D-driven increase in the expression of the Cot1-activated ERK5 protein, which is known to promote cell proliferation,49–51 is novel and unexpected.

Data presented here on the effects of Cot1 knock down or its overexpression support the hypothesis that SIL influences the induction of differentiation and inhibition of the proliferation by 1,25D through its effects on the cellular abundance of ERK5 and p27Kip1, as the most marked effects are seen when SIL and 1,25D are combined. However, it is likely that ERK5 and p27Kip1 are not the only effectors of SIL action on AML cells. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that in various models of solid tumors SIL affects numerous cellular signaling systems.52–55 While the data on the effects of this polyphenol in leukemia models remain scarce, it is likely that actions of SIL in AML cells are pleiotropic and may be mediated, at least in part, by other MAPK pathways, e.g., JNK14 and PKC56 signaling as well as by changes in differentiation-related transcription factors.15

Since a highly specific inhibitor of Cot1 kinase activity is already available,57–59 our findings raise the possibility that a combination of SIL, 1,25D and a Cot1 inhibitor may improve the treatment or delay the relapse of AML. This approach may prove particularly beneficial for the more primitive, undifferentiated types of AML. Indeed, the fact that Cot INH alone was capable of inducing myeloid differentiation in KG-1a cells, and of markedly enhancing the effect of the SIL/1,25D combination (Fig. 2), suggests that the repressing effect of Cot1 in these cells may be substantial and perhaps even stronger than in the more differentiated AML blasts. This implicates high expression of Cot1 as one of the major causes for the failure of primitive types of AML cells to respond to differentiation inducers.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies.

1,25D was a kind gift from Dr. Milan Uskokovic (Bioxell). Silibinin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and the stock was prepared by dissolving in DMSO. The following antibodies: Cot1 (#sc-720), p21 (#sc-6246), p27 (#sc-1641), phospho-p27 (Ser10 #sc-12939; Thr187 #sc-16324) and Crk-L (#sc-319) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. ERK5 (#3372), phospho-ERK5 (Thr187/Tyr220, #3371), anti-rabbit (#7074) and anti-mouse (#7076) antibodies linked to HRP were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. Anti-calreticulin (#PA3-900) was purchased from Affinity BioReagents. The pharmacological inhibitor of Cot1 kinase, 4-(3-chloro-4-f luorophenylamino)-6-(pyridin-3-yl-methylamino-3-cyano-[1-7]-naphthyridine) (#616373), was purchased from EMD Chemicals. Nitrocellulose membranes were purchased from Amersham.

Cell lines.

HL60-G cells (FAB M2), subcloned from HL60 cells derived from a patient with promyeloblastic leukemia, U937 monoblastic cells (FAB M4), derived from a patient with histiocytic lymphoma, promyeloblastic KG-1a cells (FAB M1)35 and monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells (FAB M5)60 were cultured in suspension under conditions standard in this laboratory.34 Routine microbiology testing for Mycoplasma was performed by selective culture techniques. For all experiments the cells were suspended for the indicated times in a fresh medium containing 1,25D, SIL or the equivalent volume of ethanol as a vehicle control. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Patient's blood for ex vivo studies.

Leukemic cells were obtained from patients with newly diagnosed AML following informed consent, in accordance with an IRB approved clinical protocol. All patients met the criteria for the diagnosis, based on WHO, and the diagnosis was confirmed in each case by a formal histopathologic review. The study population comprised four male subjects and two female subjects with a median age of 57 years. According to FAB classification of AML42 there were two patients with subtype M2; one with 46, XX; +21, del 7, FLT-3 wild type, nucleophosmin wild type, and one with del(11q23) involving the MLL-1 gene, and a history of prior chemotherapy for breast cancer. Two patients had histologic subtype M5: one had a karyotype showing a t(6;11) involving the MLL-1 gene; the other, subtype M5a, had trisomy 21 in the leukemic cells and increased numbers of internal tandem repeats in the FLT-3 proto-oncogene. One patient had FAB histologic subtype M4 with a normal karyotype and mutated nucleophosmin; and one patient had FAB histological subtype M6, with del(5q).

Isolation and propagation of mononuclear cells from patient's bone marrow and peripheral blood and determination of markers of differentiation.

These procedures were described in a recent publication from this laboratory.15

Cell differentiation and viability.

The expression of cell surface markers of myeloid differentiation was determined by dual labeling of the cells with 0.5 µg anti-CD11b MO1-FITC and 0.5 µg anti-CD14 My4-RD-1 (Beckman Coulter) followed by two-parameter flow cytometric analysis, as described previously in reference 15. Cell number and viability were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay, counting the proportion of viable cells in a Vi-Cell XR cell viability analyzer (Beckman Coulter).

Cycle cycle analysis.

Cells were fixed in 75% ethanol at −20°C for 24 h followed by incubation with RNase (1 µg/ml, Sigma) and propidium iodide (PI, 10 µg/ml, Sigma) for 30 min at 37°C. DNA histograms were analyzed in PI stained cells by flow cytometry, as described previously in reference 44.

Immunoprecipitation and kinase activity of Cot1.

Cell lysates (200 µl containing 200 µg of total protein) were mixed with 5 µl of Cot1 polyclonal antibody and incubated with gentle rocking at 4°C for 2 h. Then 30 µl of protein A/G agarose beads were added for another 2 h. The samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 s at 4°C. The pellets were washed twice with ice-cold cell lysis buffer, and then twice with 1x kinase buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 nM MgCl2) and kept on ice. The kinase reaction was performed in 40 µl 1× kinase buffer supplemented with 10 µM ATP and 1 µg of human recombinant MEK-1 (Santa Cruz, #sc-4025), incubated at 30°C for 30 min. In indicated experiments, 5 µM Cot1 inhibitor or 10 µM SB202190 (negative control) were added to the mixture for 10 min prior to the kinase assay. Reaction was terminated by the addition of 20 µl 3× SDS sample buffer, followed by boiling for 5 min. The beads were then collected by centrifugation and the supernatants were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham). The membranes were probed with phospho-MEK-1 (Ser217/Ser221, Cell Signaling, #9121) polyclonal antibody, and after the stripping were re-probed with anti-MEK-1 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, #sc-448), as a loading control. Signal detection was accomplished using a chemiluminescence Pierce® ECL system (Thermo Scientific). The OD of each band was quantitated using an image quantitator (Molecular Dynamics).

Western blotting.

This was performed using whole cell extracts, as described previously in reference 34. The protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence Pierce® ECL system (Thermo Scientific), and the optical density of each band was quantitated using an ImageQuant 5.0 (Molecular Dynamics).

Transient transfection of small interfering (si) RNA.

siRNA targeting Cot1 and generic scrambled control siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon. siRNAs (5 µM) were transfected into cells using Amaxa nucleofector system according to the manufacturer's protocol (solution T and program T-19). The cells were allowed to recover for 48 h and checked for the reduction of Cot1 mRNA and protein expression. Transfected cells were seeded at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml and exposed to the specified agents for the indicated times.

Stable transfection of IRES-Cot1 and cell sorting.

Full-length Cot1 DNA was generated by PCR and subcloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen). A kinase inactive Cot1 mutant was generated by mutating Lys167 to Arg in the wild type construct using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All constructs generated were verified by DNA sequencing. Cot1 stable transfectants were generated by transfecting a 5 µg of pEF-IRES2-EGFP expression vector containing Cot1 fragment (pIRES-Cot1) into HL60 or U937 cells by Amaxa Nucleofector according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following recovery for 48–72 h, cells were sorted on the basis of EGFP fluorescence by flow cytometry to derive >95% EGFP-positive cells. Cot1-transfected cells were further selected with G418 (10 ng/ml) for 2–3 weeks. Enhanced Cot1 expression was confirmed by western blot analysis.

Statistical methods.

Each experiment was performed at least three times and the results were expressed as percentages (mean ± SD) of the vehicle controls. Significance of the differences between mean values was assessed by a two-tailed Student's t-test. All computations were performed with an IBM-compatible personal computer and used Microsoft EXCEL.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiangwen Chen-Deutsch for the isolation of the patient's mononuclear cells. The study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute (Grants RO1-CA-117942-3 to G.P.S. and M.D., RO1-CA44722 to G.P.S.), the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 778/07 to M.D.), and the Foundation for Polish Science (to E.G.).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/13790

References

- 1.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:7176. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardia A, Tleyjeh IM, Cerhan JR, Sood AK, Limburg PJ, Erwin PJ, et al. Efficacy of antioxidant supplementation in reducing primary cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:23–34. doi: 10.4065/83.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dotan Y, Lichtenberg D, Pinchuk I. No evidence supports vitamin E indiscriminate supplementation. Biofactors. 2009;35:469–473. doi: 10.1002/biof.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenlee H, Hershman DL, Jacobson JS. Use of antioxidant supplements during breast cancer treatment: a comprehensive review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:437–452. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flora K, Hahn M, Rosen H, Benner K. Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) for the therapy of liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:139, 143. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad Y, Vallerand D, Brault A, Haddad PS. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of silibinin in a rat model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep164. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polyak SJ, Morishima C, Lohmann V, Pal S, Lee DY, Liu Y, et al. Identification of hepatoprotective flavonolignans from silymarin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5995–5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914009107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neumann UP, Biermer M, Eurich D, Neuhaus P, Berg T. Successful prevention of hepatitis C virus (HCV) liver graft reinfection by silibinin mono-therapy. J Hepatol. 2010;52:951–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abenavoli L, Capasso R, Milic N, Capasso F. Milk thistle in liver diseases: past, present, future. Phytother Res. 2010;4:1423–1432. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh RP, Agarwal R. Prostate cancer chemoprevention by silibinin: bench to bedside. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:436–442. doi: 10.1002/mc.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramasamy K, Agarwal R. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by silymarin. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung CW, Gibbons N, Johnson DW, Nicol DL. Silibinin-a promising new treatment for cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10:186–195. doi: 10.2174/1871520611009030186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danilenko M, Wang Q, Wang X, Levy J, Sharoni Y, Studzinski GP. Carnosic acid potentiates the antioxidant and prodifferentiation effects of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in leukemia cells but does not promote elevation of basal levels of intracellular calcium. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1325–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q, Salman H, Danilenko M, Studzinski GP. Cooperation between antioxidants and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in induction of leukemia HL60 cell differentiation through the JNK/AP-1/Egr-1 pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:964–974. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Harrison JS, Uskokovic M, Danilenko M, Studzinski GP. Silibinin can induce differentiation as well as enhance vitamin D3-induced differentiation of human AML cells ex vivo and regulates the levels of differentiation-related transcription factors. Hematol Oncol. 2010;28:124–132. doi: 10.1002/hon.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pesakhov S, Khanin M, Studzinski GP, Danilenko M. Distinct combinatorial effects of the plant polyphenols curcumin, carnosic acid and silibinin on proliferation and apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62:811–824. doi: 10.1080/01635581003693082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson T, Danilenko M, Vassilev L, Studzinski GP. Tumor suppressor p53 status does not determine the differentiation-associated G1 cell cycle arrest induced in leukemia cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and antioxidants. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:344–350. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.4.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osborn JL, Schwartz GG, Smith DC, Bahnson R, Day R, Trump DL. Phase II Trial of Oral 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (Calcitriol) in Hormone Refractory Prostate Cancer. Urol Oncol: Seminars and Original Investigations. 1995;1:195–198. doi: 10.1016/1078-1439(95)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beer TM, Munar M, Henner WD. A Phase I trial of pulse calcitriol in patients with refractory malignancies: pulse dosing permits substantial dose escalation. Cancer. 2001;91:2431–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chadha MK, Tian L, Mashtare T, Payne V, Silliman C, Levine E, et al. Phase 2 trial of weekly intravenous 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol (calcitriol) in combination with dexamethasone for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:2132–2139. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danilenko M, Studzinski GP. Enhancement by other compounds of the anti-cancer activity of vitamin D3 and its analogs. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298:339–358. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Rao J, Studzinski GP. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase activity upregulates multiple MAP kinase pathways and potentiates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of human leukemia HL60 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:425–437. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji Y, Kutner A, Verstuyf A, Verlinden L, Studzinski GP. Derivatives of vitamins D2 and D3 activate three MAPK pathways and upregulate pRb expression in differentiating HL60 cells. Cell Cycle. 2002;1:410–415. doi: 10.4161/cc.1.6.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Posner GH, Danilenko M, Studzinski GP. Differentiation-inducing potency of the seco-steroid JK-1624F2-2 can be increased by combination with an antioxidant and a p38MAPK inhibitor which upregulates the JNK pathway. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;105:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salmeron A, Ahmad TB, Carlile GW, Pappin D, Narsimhan RP, Ley SC. Activation of MEK-1 and SEK-1 by Tpl-2 proto-oncoprotein, a novel MAP kinase kinase kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15:817–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagemann D, Troppmair J, Rapp UR. Cot protooncoprotein activates the dual specificity kinases MEK-1 and SEK-1 and induces differentiation of PC12 cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:1391–1400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiariello M, Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS. Multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways connect the cot oncoprotein to the c-jun promoter and to cellular transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1747–1758. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1747-1758.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luciano BS, Hsu S, Channavajhala PL, Lin LL, Cuozzo JW. Phosphorylation of threonine 290 in the activation loop of Tpl2/Cot is necessary but not sufficient for kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52117–52123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Channavajhala PL, Rao VR, Spaulding V, Lin LL, Zhang YG. hKSR-2 inhibits MEKK3-activated MAP kinase and NFkappaB pathways in inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:1214–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Studzinski GP. Oncoprotein Cot1 Represses Kinase Suppressors of Ras1/2 and 1, 5-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-Induced Differentiation of Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22449. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Studzinski GP. Kinase suppressor of RAS (KSR) amplifies the differentiation signal provided by low concentrations 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198:333–342. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Studzinski GP. Raf-1 signaling is required for the later stages of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of HL60 cells but is not mediated by the MEK/ERK module. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:253–260. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Wang TT, White JH, Studzinski GP. Expression of human kinase suppressor of Ras 2 (hKSR-2) gene in HL60 leukemia cells is directly upregulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and is required for optimal cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3034–3045. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Studzinski GP. Expression of MAP3 kinase COT1 is upregulated by 1, 5-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in parallel with activated c-jun during differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koeffler HP, Billing R, Lusis AJ, Sparkes R, Golde DW. An undifferentiated variant derived from the human acute myelogenous leukemia cell line (KG-1) Blood. 1980;56:265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koeffler HP. Induction of differentiation of human acute myelogenous leukemia cells: therapeutic implications. Blood. 1983;62:709–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manzel L, Macfarlane DE. Protein kinase C is not necessary for transforming growth factor beta-induced growth-arrest in leukemia cell lines. Leuk Res. 1997;21:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(96)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell MJ, Drayson MT, Durham J, Wallington L, Siu-Caldera ML, Reddy GS, et al. Metabolism of 1alpha,25(OH)2D3 and its 20-epi analog integrates clonal expansion, maturation and apoptosis during HL-60 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;149:169–183. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gocek E, Kielbinski M, Baurska H, Haus O, Kutner A, Marcinkowska E. Different susceptibilities to 1, 5-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of AML cells carrying various mutations. Leuk Res. 2010;34:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan AM, Chedid M, McGovern ES, Popescu NC, Miki T, Aaronson SA. Expression cDNA cloning of a serine kinase transforming gene. Oncogene. 1993;8:1329–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aoki M, Hamada F, Sugimoto T, Sumida S, Akiyama T, Toyoshima K. The human cot proto-oncogene encodes two protein serine/threonine kinases with different transforming activities by alternative initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22723–22732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol. 1976;33:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blagosklonny MV, Pardee AB. The restriction point of the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2002;1:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang QM, Jones JB, Studzinski GP. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 as a mediator of the G1-S phase block induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in HL60 cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rovida E, Spinelli E, Sdelci S, Barbetti V, Morandi A, Giuntoli S, et al. ERK5/BMK1 is indispensable for optimal colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1)-induced proliferation in macrophages in a Src-dependent fashion. J Immunol. 2008;180:4166–4172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy S, Kaur M, Agarwal C, Tecklenburg M, Sclafani RA, Agarwal R. p21 and p27 induction by silibinin is essential for its cell cycle arrest effect in prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2696–2707. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Studzinski GP. AKT pathway is activated by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and participates in its anti-apoptotic effect and cell cycle control in differentiating HL60 cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:447–451. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.4.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Gocek E, Liu CG, Studzinski GP. MicroRNAs181 regulate the expression of p27Kip1 in human myeloid leukemia cells induced to differentiate by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:736–741. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kato Y, Tapping RI, Huang S, Watson MH, Ulevitch RJ, Lee JD. Bmk1/Erk5 is required for cell proliferation induced by epidermal growth factor. Nature. 1998;395:713–716. doi: 10.1038/27234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buzzi N, Colicheo A, Boland R, de Boland AR. MAP kinases in proliferating human colon cancer Caco-2 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;328:201–208. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inesta-Vaquera FA, Campbell DG, Tournier C, Gomez N, Lizcano JM, Cuenda A. Alternative ERK5 regulation by phosphorylation during the cell cycle. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1829–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyagi A, Singh RP, Ramasamy K, Raina K, Redente EF, Dwyer-Nield LD, et al. Growth inhibition and regression of lung tumors by silibinin: modulation of angiogenesis by macrophage-associated cytokines and nuclear factorkappaB and signal transducers and activators of transcription 3. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:74–83. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu K, Zeng J, Li L, Fan J, Zhang D, Xue Y, et al. Silibinin reverses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in metastatic prostate cancer cells by targeting transcription factors. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1545–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Velmurugan B, Gangar SC, Kaur M, Tyagi A, Deep G, Agarwal R. Silibinin Exerts Sustained Growth Suppressive Effect against Human Colon Carcinoma SW480 Xenograft by Targeting Multiple Signaling Molecules. Pharm Res. 2010;27:2085–2097. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deep G, Agarwal R. Antimetastatic efficacy of silibinin: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential against cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:447–463. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9237-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang SN, Lee MH, Kim KM, Cho D, Kim TS. Induction of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cell differentiation into monocytes by silibinin: involvement of protein kinase C. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:1487–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gavrin LK, Green N, Hu Y, Janz K, Kaila N, Li HQ, et al. Inhibition of Tpl2 kinase and TNFalpha production with 1,7-naphthyridine-3-carbonitriles: synthesis and structure-activity relationships. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:5288–5292. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu Y, Green N, Gavrin LK, Janz K, Kaila N, Li HQ, et al. Inhibition of Tpl2 kinase and TNFalpha production with quinoline-3-carbonitriles for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:6067–6072. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirata K, Taki H, Shinoda K, Hounoki H, Miyahara T, Tobe K, et al. Inhibition of tumor progression locus 2 protein kinase suppresses receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis through downregulation of the c-Fos and nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 genes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:133–137. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) Int J Cancer. 1980;26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]