Abstract

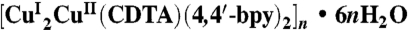

Ferroelectric materials are characterized by spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by inverting an external electric field. Owing to their unique properties, ferroelectric materials have found broad applications in microelectronics, computers, and transducers. Water molecules are dipolar and thus ferroelectric alignment of water molecules is conceivable when water freezes into special forms of ice. Although the ferroelectric ice XI has been proposed to exist on Uranus, Neptune, or Pluto, evidence of a fully proton-ordered ferroelectric ice is still elusive. To date, existence of ferroelectric ice with partial ferroelectric alignment has been demonstrated only in thin films of ice grown on platinum surfaces or within microdomains of alkali-hydroxide doped ice I. Here we report a unique structure of quasi-one-dimensional (H2O)12n wire confined to a 3D supramolecular architecture of  H4CDTA, trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; 4,4′-bpy, 4,4′-bipyridine). In stark contrast to the bulk, this 1D water wire not only exhibits enormous dielectric anomalies at approximately 175 and 277 K, respectively, but also undergoes a spontaneous transition between “1D liquid” and “1D ferroelectric ice” at approximately 277 K. Hitherto unrevealed properties of the 1D water wire will be valuable to the understanding of anomalous properties of water and synthesis of novel ferroelectric materials.

H4CDTA, trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; 4,4′-bpy, 4,4′-bipyridine). In stark contrast to the bulk, this 1D water wire not only exhibits enormous dielectric anomalies at approximately 175 and 277 K, respectively, but also undergoes a spontaneous transition between “1D liquid” and “1D ferroelectric ice” at approximately 277 K. Hitherto unrevealed properties of the 1D water wire will be valuable to the understanding of anomalous properties of water and synthesis of novel ferroelectric materials.

Keywords: ab initio molecular dynamics, phase transition, supramolecular nanochannel

An understanding of the properties of water wire and quasi-1D ice confined to a nanoscale channel has important implications for the biological sciences, geoscience, and nanoscience (1–5). The nanoscale channel can endow the water wire and 1D ice with unusual properties that differ from 3D water and ice. Hence, insights into these properties on the molecular level not only can offer explanation of intriguing phenomena such as proton and water transport in cell membranes (2) and the formation of a 1D ice tube with a water chain at the center (5), but can also assist synthesis of new nanochannels to influence the properties of water wire and 1D ice by changing the environment. In this article, our attention will be placed on the spontaneous formation of a 1D ferroelectric ice in a newly synthesized nanochannel.

Does standalone single-phase ferroelectric ice exist in nature? This question has fascinated scientists for decades (6–14). If the single-phase ferroelectric ice does exist, it would have a net polarization toward one direction (15) because of the ordered alignment of the water molecules. However, achieving a standalone and pure 3D ferroelectric ice seems to be a formidable task in the laboratory because the full phase-transformation time required for a bulk 3D ferroelectric ice is estimated to be on the order of 105 y (8, 9) without any assistance of dopants as catalysts. To date, all ferroelectric ices produced in the laboratory are low dimensional and in mixed phases (10–12). Iedema et al. (10) revealed amorphous or cubic ice films, deposited on a platinum surface, in which only about 0.2% of molecules exhibits ferroelectric alignment. Su et al. demonstrated a nanofilm of hexagonal ice, also deposited on a platinum surface, which shows a net polarization decaying with the distance from the platinum surface (11). Even protein hydration shells can be polarized into a ferroelectric cluster with a large averaged dipole moment (16). Indeed, in a low-dimensional environment, either on a substrate or in a nanochannel, the water-surface interaction may effectively hinder some protons from going to the disordered state (especially at low temperature) (17–19). Hence, well-designed nanochannels have been viewed as a promising host to realizing low-dimensional single-phase ferroelectric ice (13, 14). For example, five distinctive phases of quasi-1D ice, formed inside carbon nanotubes, have been revealed experimentally (20–23). These five 1D ice phases all exhibit single-walled tubular morphologies, including the pentagon ice nanotube (24) (provisionally named 1D ice I; ref. 18), hexagon ice nanotube (1D ice II), heptagon ice nanotube (1D ice III), octagon ice nanotube (1D ice IV), and nonagon ice nanotube (1D ice V). Additionally, a core-sheath 1D ice structure has been detected in a neutron scattering experiment (5) where the core is a single-file water chain and the sheath is an octagon ice nanotube (provisionally named as 1D ice IVa). Previous classical molecular dynamics simulations (13, 14) have suggested that the pentagon and heptagon ice nanotubes are 1D ice with mixed ferroelectric/antiferroelectric domains.

Besides the carbon nanotubes, a large number of organic and inorganic species have been successfully synthesized as hosts for confining water on the nanoscale (4, 17, 25–28). Nevertheless, species that can lead to single-phase ferroelectric ice have not been demonstrated experimentally. Recently, we reported that a water wire confined to the nanochannel [La2Cu3{NH(CH2COO)2}6]n undergoes a transition between 1D liquid and 1D antiferroelectric ice (provisionally named as 1D ice VI) at approximately 350 K (17). This finding indicates that porous metal-organic frameworks not only provide a tubular host system to understand anomalous properties of water, but also may be exploited to achieve single-phase 1D ferroelectric ice. Herein, we report the unique structure and unusual properties of 1D [(H2O)12]n wire confined to a newly synthesized nanochannel, namely, 3D supramolecular architecture of  [H4CDTA, trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; 4,4′-bpy, 4,4′-bipyridine).

[H4CDTA, trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; 4,4′-bpy, 4,4′-bipyridine).

Results and Discussion

Our single-crystal structural analysis shows that the structure of the 1D (H2O)12n wire has a periodic 12-mer framework held together by hydrogen-bonding interactions, i.e., each unit cell contains 12 water molecules. The geometry of the 12 oxygen atoms in a unit cell can be described as a six-rung ladder with one rung at one end and two rungs at another end being rotated by approximately 90° with respective to the central axis of the nanochannel, while the oxygen ladder itself is along the axial direction of the nanochannel. Measurement of the temperature-dependent dielectric constant of the water wire reveals that the water wire exhibits large dielectric anomalies at approximately 175 and 277 K, respectively, significantly different from that of bulk water. More interestingly, the measurement of temperature- and frequency-dependent dielectric constants and temperature-dependent dielectric hysteresis of the 1D water wire indicates that the 1D wire undergoes a phase transition between 1D ferroelectric ice and 1D liquid at approximately 277 K. A single-phase ferroelectric ice is now produced within a nanochannel.

This 1D ice is spontaneously formed within a 3D supramolecular architecture of  (1) (Dataset S1) prepared by the reaction of H4CDTA (0.364 g, 1.0 mmol), Cu(CH3COO)2•H2O (0.199 g, 1.0 mmol), 4,4′-bpy (0.156 g, 1.0 mmol), and 10 mL water under the hydrothermal condition. Crystallographic analysis at 123 K indicates that the asymmetric unit of (1) contains half an independent divalent CuII ion, one monovalent CuI, half a CDTA4- ligand, one 4,4′-bpy ligand, and three water molecules. Each CuII ion, located in the octahedral structure, is coordinated by two N atoms and four modentate carboxylate groups from one CDTA4- ligand to form a metalloligand [CuIICDTA]2-. Each CuI ion, located in the T-shaped structure, is coordinated by two N atoms, respectively, from two 4,4′-bpy ligands and one monodentate carboxylate group from one metalloligand [CuIICDTA]2- (Fig. 1A). The T-shaped coordination mode for the copper ion indicates existence of the CuI species, consistent with the observation of magnetic property of (1) (Fig. S1).

(1) (Dataset S1) prepared by the reaction of H4CDTA (0.364 g, 1.0 mmol), Cu(CH3COO)2•H2O (0.199 g, 1.0 mmol), 4,4′-bpy (0.156 g, 1.0 mmol), and 10 mL water under the hydrothermal condition. Crystallographic analysis at 123 K indicates that the asymmetric unit of (1) contains half an independent divalent CuII ion, one monovalent CuI, half a CDTA4- ligand, one 4,4′-bpy ligand, and three water molecules. Each CuII ion, located in the octahedral structure, is coordinated by two N atoms and four modentate carboxylate groups from one CDTA4- ligand to form a metalloligand [CuIICDTA]2-. Each CuI ion, located in the T-shaped structure, is coordinated by two N atoms, respectively, from two 4,4′-bpy ligands and one monodentate carboxylate group from one metalloligand [CuIICDTA]2- (Fig. 1A). The T-shaped coordination mode for the copper ion indicates existence of the CuI species, consistent with the observation of magnetic property of (1) (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Ball and stick view of the coordination environment of CuI and CuII ions. (B) The 2D network [CuICuII(CDTA)(bpy)2]n viewed along the c axis. (C) The threefold interpenetration network of [CuICuII(CDTA)(bpy)2]n viewed along the c axis. (D) The threefold interpenetration network viewed along the b axis. (E) The 3D supramolecular architecture of (1) along the a axis. (F) A side view of water structures in two unit cells of the 1D water wire (H2O)12n in (1). [Note: For the three crystallographically independent water molecules in the 1D ice, they are plotted in such a way that each water molecule seems to have three hydrogen atoms, although in reality each water molecule only has two hydrogen atoms. This way of plotting is commonly used (e.g., in ref. 4) to reflect that one of the two hydrogen atoms in every water molecule is positionally disordered and thus is treated as half-occupancy as pointed out in the text. From the viewpoint of crystallography, these dynamic hydrogen atoms are alternatively hydrogen-bonded to adjacent water molecules in the 1D ice.] Red and green balls denote oxygen atoms in the front and the back positions, respectively. The blue dashed lines denote hydrogen bonds. O1–O4 are oxygen atoms of the nanochannel.

The two adjacent CuI ions, bridged by one 4,4′-bpy ligand, in which its terminal N atom coordinates with one CuI ion, forms a 1D chain of  . Connection of the adjacent 1D chains of

. Connection of the adjacent 1D chains of  through the metalloligand of [CuIICDTA]2- with its two O atoms coordinating respectively with two CuI ions from two adjacent 1D chains leads to a 2D 63 network

through the metalloligand of [CuIICDTA]2- with its two O atoms coordinating respectively with two CuI ions from two adjacent 1D chains leads to a 2D 63 network  (Fig. 1B) which further extends to a threefold interpenetration network as shown in Fig. 1 C and D. The 3D supramolecular architecture of (1) can be viewed such that the 1D water wire (H2O)12n acts as proton donor and is hydrogen bonded to the carboxylate of [CuIICDTA]2- from the adjacent threefold interpenetration networks, as illustrated in Fig. 1E.

(Fig. 1B) which further extends to a threefold interpenetration network as shown in Fig. 1 C and D. The 3D supramolecular architecture of (1) can be viewed such that the 1D water wire (H2O)12n acts as proton donor and is hydrogen bonded to the carboxylate of [CuIICDTA]2- from the adjacent threefold interpenetration networks, as illustrated in Fig. 1E.

In the 1D ice (H2O)12n, there exist three crystallographically independent water molecules, O1w, O2w, and O3w (Fig. 1F). Each O1w acts as both proton accepter and donor to connect with the adjacent two O1w, forming a cyclic water tetramer whose plane is slightly twisted but normal to the central axis of the nanochannel. Four O2w (each hydrogen-bonded to one O2w and one O3w, respectively) and four O3w (each hydrogen-bonded to one O3w and one O2w) form a cyclic and boat-like water octamer. Each crystallographically independent water molecule has a fully occupied H atom (H1wa for O1w, H2wa for O2w, and H3wa for O3w). The fully occupied H atoms for O1w and O2w are hydrogen-bonded, respectively, to O4 and O1 from carboxylate of [CuIICDTA]2-, whereas O3w is hydrogen-bonded to O1w. The remaining H atoms of the water molecules are disordered and treated as half-occupied. As a consequence, the 1D ice (H2O)12n can be viewed as a water tetramer acting as a proton acceptor and boat-like water octamer acting as a proton donor (Fig. 1F). The calculated density (29) for the 1 D ice is 1.038 g/cm3, significantly higher than that of 0.9167 g/cm3 for the bulk ice at 0 °C (7).

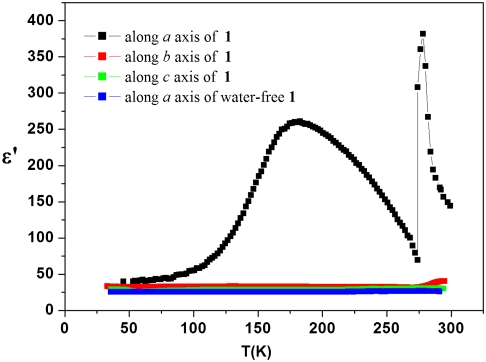

When the guest water was fully removed, the nanochannel (1) retained its structure (Fig. S2), allowing measurement of the dielectric constants for (1) and water-free (1) (E = 1.0 V, 10 kHz) from 45 to 298 K. As shown in Fig. 2, the real part of dielectric constant (ϵ′) for (1) along the a axis exhibits a large temperature dependence. It is nearly constant (ϵ′ ≈ 40) below 100 K but then rises to a broad peak with a maximum ϵ′ ≈ 260 at around 170 K. As the temperature was further raised to 298 K, a sharp dielectric peak appeared with the maximum ϵ′ ≈ 381 at around 277 K. Because the ϵ′ for (1) along the b and c axes and for water-free (1) along the a axis (ϵ′ ≈ 30) is almost temperature-independent over the entire range, we can conclude the temperature-dependent ϵ′ for (1) along the a axis corresponds to the water wire. The ϵ′ for the water wire is dramatically different from that of bulk water [ϵ′(H2O) ≈ 90 at 273 K] and exhibits high anisotropy compared to bulk water (30)

Fig. 2.

The dielectric constant (ϵ′) of (1) measured at various temperatures along the a (black), b (red), and c (green) axes, respectively. The dielectric constant (ϵ′) of water-free (1) measured at various temperatures along the a axis (blue) under the same condition (E = 1 V, f = 10 kHz).

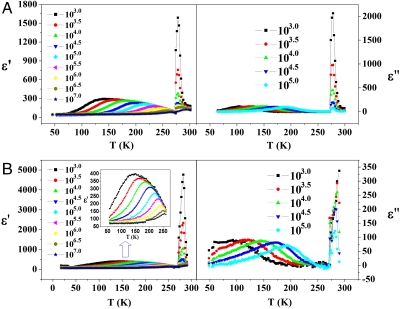

To establish the basis for the temperature-dependent behavior of the water wire, the dielectric constants for (1) and its deuterated form  (1a) (Dataset S2) along the a axis were measured at various frequencies from 1 kHz to 10 MHz. As the frequency was raised throughout this range (Fig. 3A), the broad dielectric peak for (1) shifts to high temperature and its ϵ′ decreases from 293 to 82. At first glance, the temperature- and frequency-dependent ϵ′ for (1) exhibits the characteristic behavior of a relaxor ferroelectric (the typical strong dispersion effects often being ascribed to the freezing-in of ferroelectric clusters; refs. 31 and 32). The broad dielectric peak, however, does not represent a phase transition, but a dielectric relaxation phenomena, because the broad peak of ϵ′′ for (1) [especially that for (1a)] decreases rather than increases with the increase of frequency (33).

(1a) (Dataset S2) along the a axis were measured at various frequencies from 1 kHz to 10 MHz. As the frequency was raised throughout this range (Fig. 3A), the broad dielectric peak for (1) shifts to high temperature and its ϵ′ decreases from 293 to 82. At first glance, the temperature- and frequency-dependent ϵ′ for (1) exhibits the characteristic behavior of a relaxor ferroelectric (the typical strong dispersion effects often being ascribed to the freezing-in of ferroelectric clusters; refs. 31 and 32). The broad dielectric peak, however, does not represent a phase transition, but a dielectric relaxation phenomena, because the broad peak of ϵ′′ for (1) [especially that for (1a)] decreases rather than increases with the increase of frequency (33).

Fig. 3.

Temperature dependence of the complex dielectric constant (real part ϵ′ and imaginary part ϵ′′) along a axis at different frequencies for (A) (1) and (B) (1a).

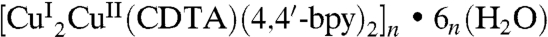

Consistent with this observation is that the temperature-dependent dielectric hysteresis revealed that no hysteretic polarization-electric field (P-E) loop was observed below 200 K when measured at various ac electric fields of triangular waveform applied along a crystallographic axis of the single crystal (Fig. 4). The ϵ′ for (1) decreases from 1,576 to 187 at 277 K (Fig. 3A), significantly larger and sharper than the decrease in the broad dielectric peak. The sharp peak of 277 K clearly indicates a dielectric phase transition (33). The significant spontaneous polarization was observed only below 277 K and the satisfactory P-E loop was obtained at approximately 250 K. The saturation polarization (Psa) of ca. 2.5 μC·cm-2 and a residual polarization (Pr) of ca. 1.75 μC·cm-2 are obtained with a coercive field (Ec) of ca. 0.83 kV·cm-1.

Fig. 4.

The dielectric hysteresis of (1) along the a axis at different temperatures. (Insets) The side and top view of the 1D ice.

Even though (1) exhibits a typical ferroelectric feature along the a axis, no P-E hysteresis loops are displayed along the b and c axes (Fig. S3). The strong anisotropy further affirms that the ferroelectricity of (1) is attributed to the water wire. These results, together with the calculated density (29) for the water wire or 1D ice [250 K(1b), 0.9946 g/cm3; 260 K(1c), 1.0108 g/cm3; 278 K(1d), 1.0328 g/cm3; and 298 K(1e), 1.0053 g/cm3] (see Datasets S3, S4, S5, and S6) obtained from crystal structures at different temperatures, show that the dielectric phase transition at 277 K is attributed to the transition between a 1D ferroelectric ice and a 1D liquid.

The temperature-dependent dielectric constants of (1a) were also examined along the a axis at various frequencies in the range of 1–10 MHz (Fig. 3). Similar to that for (1), the broad dielectric peak of for (1a) also shifts to high temperature and its ϵ′ decreases with increasing frequency, whereas the broad peak of ϵ′ for (1a) decreases with the increase of frequency. However, the maximum ϵ′ of the (1a) for the sharp peak appears at approximately 285 K, which is approximately 8 K higher than that for (1), showing the “deuteration effect” that influences the phase transition temperature of the water wire.

Given that (1) crystallizes with a the centrosymmetric space group Fddd, what causes the ferroelectricity of the water wire? To address this question, the structure of water wire was analyzed in greater detail. Even though the positions of oxygen atoms in the crystal structure can be fully determined from the X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiment, the exact positions of hydrogen atoms cannot. As mentioned above, however, O1w and O2w each hydrogen-bond with O1 and O4 in the host nanochannel, thereby hindering the tendency for disordered hydrogen atoms. This hindrance limits the orientation of remaining hydrogen atoms of O1w and O2w, so they can only rotate along the axis of the O1⋯O1w and O4⋯O2w, respectively, to maximize hydrogen-bonding interactions in the water wire.

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation (see Materials and Methods) was carried out to study the positions of the water molecules within the nanochannel. We selected one channel (containing 256 atoms, including 12 H2O molecules) as the model system for the AIMD simulation. All the dangling bonds on the outer surface of the nanochannel were terminated by hydrogen atoms. All the heavy atoms (except hydrogen) on the wall were fixed to the XRD measured positions, and they were not relaxed during the geometry optimization and AIMD simulation. The initial orientations of hydrogen atoms were randomly assigned. During the 12.5-ps AIMD simulation (with temperature fixed at 300 K), we observed little movement in oxygen atom positions but considerable rotation of water molecules, which results in the continual formation and breaking of intermolecular hydrogen bonds (see Movie S1). The oxygen atom positions near the end of the simulation are in good agreement with the experimental values, as can be seen when comparing Fig. 1F with a snapshot of AIMD at 10 ps (Fig. 5A). In addition, based on the optimized structure of the 12 water molecules within the nanochannel, we also estimated their net dipole moment which amounts to approximately 9 D (or 0.75 D per water molecule). For this estimation, we used the simple-point-charge (SPC) water model with which each water has a dipole moment of 2.27 D (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 5.

(A) A snapshot of water molecules (plotted in a ball and stick model) and vicinal atoms of nanochannel (plotted in a line model) at 10 ps from an AIMD simulation with temperature controlled at 300 K. Classical MD snapshots of the 1D ice in an external electric field whose direction is (B) along the -a axis and (C) along the a axis, respectively. In B and C, the red and green balls denote to O and H atoms, respectively, and the orange dashed lines denote hydrogen bonds.

To gain more insight into the positions of hydrogen atoms under an external electric field and to evaluate the magnitude of polarization under the external field, classical molecular dynamic simulation was employed (see Materials and Methods). In the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, all the oxygen atoms were fixed at the positions determined by the measured crystal structure while the orientations of O-H bonds were allowed to relax. From a snapshot of 1D ice under the external electric field in the a direction, one can see that one hydrogen atom of the O1w forms a hydrogen bond either with symmetry-related O1w (Fig. 5B) or the symmetry-related O3w (Fig. 5C). Likewise, one hydrogen atom of O2w forms a hydrogen bond either with O3w (Fig. 5B) or symmetry-related O2w (Fig. 5C). For the O3w, one hydrogen atom either forms a hydrogen bond with O2w or symmetry-related O3w. Note that the snapshots in Fig. 5 B and C show states in which most O-H bonds point along the electric field, and that the snapshots in Fig. 5 B and C have the opposite electric field directions. The average dipole moment per 12 water molecules in a channel along the a axis (Pa) is -25.1 and 25.0 D, respectively, in two opposite fields. Clearly, the hydrogen-bonding interactions among water molecules in the water wire and the host (1) is of critical importance to the inherent ferroelectricity of the 1D ice. The water-host hydrogen bonds do not break and reform while the remaining hydrogen atoms of the water molecules in the 1D ice rotate alternately under the opposite electric field. As a result, the polarity of the 1D ice can be reversed by reversing the external electric field, as shown in Fig. 5 B and C. Consistent with this structural explanation is that the magnitude of ϵ′ (about 1,576) with f = 1 kHz at 277 K was nearly 40 times larger than at 50 K (Fig. 4). The dielectric phase transition is due to molecular motion rather than fast electronic motion (34).

Water is the most abundant liquid on Earth and it plays a key role in many biological and chemical processes and material sciences (35). However, its role in many phenomena is not fully understood despite a myriad of studies (36–38). Here, based on the confinement within the 3D supramolecular architecture of  , we have produced a 1D ice (H2O)12n. Single-crystal analysis revealed that the 1D ice, comprised of 12 water molecules in a unit cell, can be viewed as a water tetramer that acts as a proton acceptor for a proton-donating boat-like water octamer. Investigation on the temperature-dependent dielectric constant of (1) indicates that this water wire exhibits large dielectric anomalies at around 175 and 277 K, dramatically different from that of bulk water and ice XI (6–10, 37), and acts as a single-phase 1D ferroelectric ice below 277 K. Analysis of the ferroelectric mechanism for the water wire shows that both dynamic hydrogen-bonding interactions among water molecules in the water wire and static interactions between water molecules and the host play key roles. Hence, our study points out a viable route to the synthesis of ferroelectric materials by taking advantage of the diversity and tunability of water within metal-organic frameworks.

, we have produced a 1D ice (H2O)12n. Single-crystal analysis revealed that the 1D ice, comprised of 12 water molecules in a unit cell, can be viewed as a water tetramer that acts as a proton acceptor for a proton-donating boat-like water octamer. Investigation on the temperature-dependent dielectric constant of (1) indicates that this water wire exhibits large dielectric anomalies at around 175 and 277 K, dramatically different from that of bulk water and ice XI (6–10, 37), and acts as a single-phase 1D ferroelectric ice below 277 K. Analysis of the ferroelectric mechanism for the water wire shows that both dynamic hydrogen-bonding interactions among water molecules in the water wire and static interactions between water molecules and the host play key roles. Hence, our study points out a viable route to the synthesis of ferroelectric materials by taking advantage of the diversity and tunability of water within metal-organic frameworks.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

For  (1), trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid monohydrate (H4CDTA, 0.364 g, 1.0 mmol), copper acetate (Cu(CH3COO)2•H2O, 0.199 g, 1.0 mmol), 4,4′-bipyridine (4,4′-bpy, 0.156 g, 1.0 mmol), and 10 mL distilled water were mixed while stirring at room temperature. When the pH of the mixture was adjusted to about 3 with 1.0 mol·L-1 nitric acid, the solution was put into a 25-mL Teflon-lined Parr, heated to 150 °C for 3 d, and then cooled to room temperature at a rate of

(1), trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid monohydrate (H4CDTA, 0.364 g, 1.0 mmol), copper acetate (Cu(CH3COO)2•H2O, 0.199 g, 1.0 mmol), 4,4′-bipyridine (4,4′-bpy, 0.156 g, 1.0 mmol), and 10 mL distilled water were mixed while stirring at room temperature. When the pH of the mixture was adjusted to about 3 with 1.0 mol·L-1 nitric acid, the solution was put into a 25-mL Teflon-lined Parr, heated to 150 °C for 3 d, and then cooled to room temperature at a rate of  . Red stick crystals of (1) were collected in a yield of 30% based on Cu. Analysis calculated for C34H46Cu3N6O14 (1) is as follows: C, 42.83; H, 4.86; N, 8.81; found: C, 42.99; H, 4.61; N, 8.68. IR (KBr pellet, cm-1): 3,431 s (strong); 3,044 w (weak); 2,929 m (moderate); 2,858 w; 1,602 s; 1,531 w; 1,483 m; 1,408 s; 1,255 w; 1,216 m; 1,103 w; 993 w; 916 w; 891 w; 819 m; 800 m; 727 w; 633 w; 570 w; 476 w.

. Red stick crystals of (1) were collected in a yield of 30% based on Cu. Analysis calculated for C34H46Cu3N6O14 (1) is as follows: C, 42.83; H, 4.86; N, 8.81; found: C, 42.99; H, 4.61; N, 8.68. IR (KBr pellet, cm-1): 3,431 s (strong); 3,044 w (weak); 2,929 m (moderate); 2,858 w; 1,602 s; 1,531 w; 1,483 m; 1,408 s; 1,255 w; 1,216 m; 1,103 w; 993 w; 916 w; 891 w; 819 m; 800 m; 727 w; 633 w; 570 w; 476 w.

Crystal data for (1) are as follows: Red crystal, 0.36 × 0.32 × 0.30 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.8037(5) Å, b = 24.8742(12) Å, c = 51.423(3) Å, V = 15,098.1(12) Å3, Mr = 953.39, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.678 g cm-3, μ = 1.752 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 123(2) K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int ) = 0.0312. Of the 10,335 reflections collected, 3,713 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0312) and 2,745 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 255 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.0441, wR2(observed) = 0.1261, R1(all data) = 0.0538, and wR2(all data) = 0.1326 were obtained, goodness of fit refine  .

.

Crystal data for (1b) are as follows: Red crystal, 0.36 × 0.32 × 0.30 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.7658(5) Å, b = 25.2769(16) Å, c = 51.469(3) Å, V = 15,307.1(14) Å3, Mr = 953.39, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.655 g cm-3, μ = 1.728 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 250(2) K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int ) = 0.0341. Of the 10,676 reflections collected, 3,676 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0341) and 2,612 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 255 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.0409, wR2(observed) = 0.1111, R1(all data) = 0.0653, and wR2(all data) = 0.1194 were obtained, GOF = 1.003

Crystal data for (1c) are as follows: Red crystal, 0.36 × 0.32 × 0.30 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.7630(6) Å, b = 25.1910(18) Å, c = 51.501(3) Å, V = 15,260.9(16) Å3, Mr = 953.39, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.660 g cm-3, μ = 1.733 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 260(2) K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int ) = 0.0369. Of the 10,633 reflections collected, 3,755 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0369) and 2,521 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 255 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.036, wR2(observed) = 0.1153, R1(all data) = 0.0719, and wR2(all data) = 0.1245 were obtained, GOF = 1.015.

Crystal data for (1d) are as follows: Red crystal, 0.36 × 0.32 × 0.30 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.7584(6) Å, b = 25.0390(19) Å, c = 51.481(3) Å, V = 15,157.1(17) Å3, Mr = 953.39, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.671 g cm-3, μ = 1.745 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 277(2) K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int ) = 0.0405. Of the 10,619 reflections collected, 3,730 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0405) and 2,428 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 255 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.0473, wR2(observed) = 0.1191, R1(all data) = 0.0818, and wR2(all data) = 0.1315 were obtained, GOF = 1.040.

Crystal data for (1e) are the following: Red crystal, 0.36 × 0.32 × 0.30 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.7658(4) Å, b = 25.2002(17) Å, c = 51.440(2) Å, V = 15,252.0(13) Å3, Mr = 953.39, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.661 g cm-3, μ = 1.734 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 298(2)K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int) = 0.0287. Of the 9,254 reflections collected, 3,757 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0287) and 2,745 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 255 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.0423, wR2(observed) = 0.1060, R1(all data) = 0.0718, and wR2(all data) = 0.1115 were obtained, GOF = 1.011.

(1a) was prepared in a similar way as described for (1), expect for using 10 mL deuterium oxide to replace water. Red crystals were obtained in a 25% yield based on Cu. Analysis calculated for C34H34D12Cu3N6O14 (1a) is as follows: C, 42.30; N, 8.70; found: C, 43.52; N, 8.66. IR (KBr pellet): 3,428 s; 3,073 w; 3,043 w; 2,932 w; 2,864 w; 1,601 s; 1,528 w; 1,483 m; 1,408 s; 1,215 m; 1,137 w; 1,063 w; 993 w; 954 w; 935 w; 875 m; 818 m; 800 m; 724 w; 633 w; 570 w; 476 w. Crystal data for 1a are red crystal, 0.30 × 0.15 × 0.08 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.7434(19) Å, b = 24.892(4) Å, c = 50.997(8) Å, V = 14,907(4) Å3, Mr = 965.46, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.721 g cm-3, μ = 1.774 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 123(2) K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int) = 0.0295. Of the 19,439 reflections collected, 3,654 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0295) and 3,286 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 258 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.0509, wR2(observed) = 0.1331, R1(all data) = 0.0557, and wR2(all data) = 0.1296 were obtained, GOF = 1.042.

(1a) was prepared in a similar way as described for (1), expect for using 10 mL deuterium oxide to replace water. Red crystals were obtained in a 25% yield based on Cu. Analysis calculated for C34H34D12Cu3N6O14 (1a) is as follows: C, 42.30; N, 8.70; found: C, 43.52; N, 8.66. IR (KBr pellet): 3,428 s; 3,073 w; 3,043 w; 2,932 w; 2,864 w; 1,601 s; 1,528 w; 1,483 m; 1,408 s; 1,215 m; 1,137 w; 1,063 w; 993 w; 954 w; 935 w; 875 m; 818 m; 800 m; 724 w; 633 w; 570 w; 476 w. Crystal data for 1a are red crystal, 0.30 × 0.15 × 0.08 mm3, orthorhombic, space group Fddd with a = 11.7434(19) Å, b = 24.892(4) Å, c = 50.997(8) Å, V = 14,907(4) Å3, Mr = 965.46, Z = 16, ρcalcd = 1.721 g cm-3, μ = 1.774 mm-1, F000 = 7,856, T = 123(2) K, 2θmax = 52.00°, R(int) = 0.0295. Of the 19,439 reflections collected, 3,654 are independent reflections (Rint = 0.0295) and 3,286 are observed reflections [I > 2σ(I)]. On the basis of all these data and 258 refined parameters, R1(observed) = 0.0509, wR2(observed) = 0.1331, R1(all data) = 0.0557, and wR2(all data) = 0.1296 were obtained, GOF = 1.042.

Crystal Structure Determination.

Data were collected with one single crystal on Oxford Gemini S Ultra using Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073) and equipped with Oxford Instruments at 123 K for (1), 250 K for (1b), 260 K for (1c), 277 K for (1d), and 298 K for (1e) (Datasets S1, S3, S4, S5, and S6). Data of (1a) were collected on a Bruker SMART Apex CCD diffractometer using graphite-monochromatized Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073) at 123 K (Dataset 2). Absorption corrections were applied using the multiscan program SADABS. The structures were solved by direct methods (SHELXTL, version 5.10), and the non-H-atoms were refined anisotropically by a full-matrix least-squares method on F2. CCDC 800743–800748 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper as well. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Physical Measurements.

Temperature-dependent dielectric constants were measured using the two-probe ac impedance method for frequencies from 1 kHz to 10 MHz (Wayne Kerr 6500B). A single crystal was placed into a cryogenic refrigeration system (Oxford Cyromech). The electrical contacts were prepared using gold paste (Tokuriki 8560) to attach 25-μm gold wires to the single crystal. The P-E curve was measured using Radiant Precision Premier II.

Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Simulation.

Ab initio (Born-Oppenheimer) molecular dynamics simulation was performed using the QUICKSTEP program implemented in the CP2K package (39, 40). The Becke-Lee-Yang-Parr (41, 42) exchange correlation functional was selected, and the empirical dispersion correction (43, 44) to the density-functional theory (DFT) calculation (i.e., DFT-D calculation) was used to model the intermolecular dispersion. The Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) (45) norm-conserved pseudopotentials were utilized to account for the contribution of the core electrons. We also used the GTH-double-zeta-polarization Gaussian basis set along with a plane-wave basis set (with an energy cutoff of 280 Ryd) for the expansion of electronic wavefunctions. The AIMD simulation was performed in a constant-volume and constant-temperature ensemble with the temperature controlled at 300 K. The simulation cell contains 256 atoms, including 12 water molecules. The total AIMD simulation time was 12.5 ps (Movie S1).

Classical Molecular Dynamics Simulation.

The classical MD simulations were performed using the Discover program implemented in the Material Studio 4.4 package (46). The consistent-valence force field was used with the atomic charges derived from the charge equilibration (47) method for the supramolecular structure, and the SPC (48) model was used for water. The simulation cell contains 1,648 atoms, including 96 water molecules. The initial structure was equilibrated at 290 K for 1 ns. After the equilibration, two additional MD simulations were performed, one in the external electric field (5.14 V/nm) along the 1D water wire, and another in opposite direction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

X.C.Z. is grateful to Prof. Mark Griep for his critical reading of the manuscript. Xiamen University group is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 20825103, 20721001, and 90922031) and the 973 project (Grant 2007CB815304) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln group is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grants CHE-0701540 and CBET-1036171), Army Research Office (Grant W911NF1020099), Nebraska Research Initiative, and University of Nebraska’s Holland Computing Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1010310108/-/DCSupplemental.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom, www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif (CSD reference nos. 800743–800748).

References

- 1.Hummer G, Rasaiah JC, Noworyta JP. Water conduction through the hydrophobic channel of a carbon nanotube. Nature. 2001;414:188–190. doi: 10.1038/35102535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sansom MSP, Biggin PC. Water at the nanoscale. Nature. 2001;414:156–159. doi: 10.1038/35102651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinger NE. Water in confinement. Science. 2002;298:1722–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1079322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheruzel LE, et al. Structures and solid-state dynamics of one-dimensional water chains stabilized by imidazole channels. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:5452–5455. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolesnikov AI, et al. Anomalously soft dynamics of water in a nanotube: A revelation of nanoscale confinement. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:035503-1–035503-4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.035503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bramwell ST. Ferroelectric ice. Nature. 1999;397:212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrenko VF, Whiteworth RW. Physics of Ice. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukazawa H, Hoshikawa A, Ishii Y, Chakoumakos BC, Fernandez-Baca JA. Existence of ferroelectric ice in the universe. Astrophys J. 2006;652:L57–L60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukazawa H, Hoshikawa A, Chakoumakos BC, Fernandez-Baca JA. Existence of ferroelectric ice on planets—a neutron diffraction study. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A. 2009;600:279–281. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iedema MJ, et al. Ferroelectricity in water ice. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:9203–9214. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su X, Lianos L, Shen R, Somorjai GA. Surface-induced ferroelectric ice on Pt(111) Phys Rev Lett. 1998;80:1533–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson SM, Whitworth RM. Thermally-stimulated depolarization studies of the ice XI-Ice Ih phase transition. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:6177–6179. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo CF, Fa W, Zhou J, Dong JM, Zeng XC. Ferroelectric ordering in ice nanotubes confined in carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2607–2612. doi: 10.1021/nl072642r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikami F, Matsuda K, Kataura H, Maniwa Y. Dielectric properties of water inside single-walled carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2009;3:1279–1287. doi: 10.1021/nn900221t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lines ME, Glass AM. Principles and Applications of Ferroelectrics and Related Materials. New York: Oxford UnivPress; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeBard DN, Matyushov DV. Ferroelectric hydration shells around proteins: Electrostatics of the protein/water interface. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:9246–9258. doi: 10.1021/jp1006999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui HB, et al. A porous coordination-polymer crystal containing one-dimensional water wires exhibits guest-induced lattice distortion and a dielectric anomaly. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:3376–3380. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai JE, Wang J, Zeng XC. Multiwalled ice helixes and ice nanotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19664–19667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608401104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop Cl, et al. On thin ice: Surface order and disorder during pre-melting. Faraday Discuss. 2009;141:277–291. doi: 10.1039/b807377p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniwa Y, et al. Phase transition in confined water inside carbon nanotubes. J Phys Soc Jpn. 2002;71:2863–2866. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh S, Ramanathan KV, Sood AK. Water at nanoscale confined in single-walled carbon nanotubes studied by NMR. Europhys Lett. 2004;65:678–684. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maniwa Y, et al. Ordered water inside carbon nanotubes: Formation of pentagonal to octagonal ice-nanotubes. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;401:534–538. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byl O, et al. Unusual hydrogen bonding in water-filled carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12090–12097. doi: 10.1021/ja057856u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koga K, Gao GT, Tanaka H, Zeng XC. Formation of ordered ice nanotubes inside carbon nanotubes. Nature. 2001;412:802–805. doi: 10.1038/35090532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Febles M, et al. Distinct dynamic behaviors of water molecules in hydrated pores. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10008–10009. doi: 10.1021/ja063223j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheruzel LE, et al. Structures and solid-state dynamics of one-dimensional water wires stabilized by imidazole channels. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:5452–5455. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janiak C, Scharamann TG. Two-dimensional water and ice layers: Neutron diffraction studies at 278, 263 and 20 K. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14010–14011. doi: 10.1021/ja0274608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long LS, Wu YR, Huang RB, Zheng LS. A well-resolved uudd cyclic water tetramer in crystal host of [Cu(adipate)(4,4-bipyridine)] (H2O)2. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:3798–3800. doi: 10.1021/ic0494354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spek AL. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J Appl Cryst. 2003;36:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murrell JN, Jenkins AD. Properties of Liquids and Solutions. 2nd Ed. Chichester, England: Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samara GA. The relaxation properties of compositionally disordered ABO3 perovskites. J Phys Condens Matter. 2003;15:R367–R411. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cross LE. Relaxor ferroelectrics. Ferroelectrics. 1987;76:241–267. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horiuchi S, Kumai R, Tokunaga Y, Tokura Y. Proton dynamics and room-temperature ferroelectricity in anilate salts witha proton sponge. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13382–13391. doi: 10.1021/ja8032235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao KC. Dielectric Phenomena in Solids. San Diego: Elsevier; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratt LR. Introduction: Water. Chem Rev. 2002;102:2625–2626. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zubavicus Y, Grunze M. New sights into the structure of water with ultrafast probes. Science. 2004;304:974–976. doi: 10.1126/science.1097848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singer SJ, et al. Hydrogen-bond topology and the ice VII/VIII and ice Ih/XI proton-ordering phase transitions. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:135701.1–135701.4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.135701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Run CY, Lobastov VA, Vigliotti F, Chen S, Zewail AH. Ultrafast electron crystallography of interfacial water. Science. 2004;304:80–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1094818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VandeVondele J, et al. Quickstep: Fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput Phys Commun. 2005;167:103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippert G, Hutter J, Parrinello M. A hybrid Gaussian and plane wave density functional scheme. Mol Phys. 1997;92:477–487. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becke AD. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3010. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grimme S. Accurate description of van der Waals complexes by density functional theory including empirical corrections. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1463–1473. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:1787–1799. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hartwigsen C, Goedecker S, Hutter J. Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys Rev B. 1998;58:3641–3662. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Materials Studio. San Diego: Accelrys; 2008. Version 4.4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dauber-Osguthorpe P, et al. Structure and energetics of ligand binding to proteins: E. coli dihydrofolate reductase-trimethoprim, a drug receptor system. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 1988;4:31–47. doi: 10.1002/prot.340040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rappé AK, Goddard WA., III Charge equilibration for molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem. 1991;95:3358–3363. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.