Abstract

Neonatal maternal separation alters adult learning and memory. Previously, we showed that neonatal separation impaired eyeblink conditioning in adult rats and increased glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression in the cerebellar interpositus nucleus, a critical site of learning-related plasticity. Daily neonatal separation (1h/day on postnatal days 2-14) increases neonatal plasma corticosterone levels. Therefore, effects of separation on GR expression in the interpositus and consequently adult eyeblink conditioning may be mediated by neonatal increases in corticosterone. As a first step in exploring a potential role for corticosterone in the neonatal separation effects we observed, we assessed whether systemic daily (postnatal days 2-14) corticosterone injections mimic neonatal separation effects on adult eyeblink conditioning and GR expression in the interpositus. Control uninjected animals were compared to animals receiving either daily corticosterone injections or daily injections of an equal volume of vehicle. Plasma corticosterone values were measured in a separate group of control, neonatally separated, vehicle injected, or corticosterone injected pups. In adulthood, rats underwent surgery for implantation of recording and stimulating electrodes. After recovery from surgery, rats underwent 10 daily sessions of eyeblink conditioning. Then, brains were processed for GR immunohistochemistry and GR expression in the interpositus nucleus was assessed. Vehicle and corticosterone injections both produced much larger increases in neonatal plasma corticosterone than did daily maternal separation, with the largest increases occurring in the corticosterone-injected group. Neonatal corticosterone injections impaired adult eyeblink conditioning and decreased GR expression in the interpositus nucleus, while the effects of vehicle injections were intermediate. Thus, while neonatal injections and maternal separation both produce adult impairments in learning and memory, these manipulations produce opposite changes in GR expression. This suggests an inverted U-shaped relationship may exist between both neonatal corticosterone levels and adult GR expression in the interpositus nucleus, and adult GR expression in the interpositus and eyeblink conditioning.

Keywords: Eyeblink conditioning, maternal separation, neonatal stress, injection stress, neonatal corticosterone, glucocorticoid receptors, learning and memory

1.1

Adverse early experience is associated with the development of many psychiatric disorders (Salk et al., 1985, Lizardi et al., 1995, Glod and Teicher, 1996, Cortes et al., 2005), including schizophrenia (van Os and Selten, 1998, Edwards, 2007). In animal models, adverse effects of neonatal stressors such as maternal separation include increased adult emotionality and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsivity to stress (McIntosh et al., 1999, Kalinichev et al., 2002, De Jongh et al., 2005). Maternal separation also produces changes in adult learning and memory. For instance, neonatal maternal separation results in adult impairments in spatial learning and memory (Huot et al., 2002, Uysal et al., 2005, Aisa et al., 2007, Aisa et al., 2009) and extinction of conditioned fear (Stevenson et al., 2009, Wilber et al., 2009). However, some forms of learning and memory may be facilitated by maternal separation; for example, adult active avoidance learning is enhanced following neonatal maternal separation (Schäble et al., 2007). Finally, cerebellar activity is altered in humans with schizophrenia (Andreasen and Pierson, 2008), and animal models show that adverse early experience, including maternal deprivation, produces changes in the cerebellum that may contribute to schizophrenia-like behaviors (López-Gallardo et al., 2008, Laviola et al., 2009).

Eyeblink conditioning provides a simplified and well-characterized model system for exploring the mechanisms of neonatal stress effects on adult learning and memory. Eyeblink conditioning involves pairing a tone with a mild shock to the eye region (an unconditioned stimulus; US). With training, the tone (conditioned stimulus; CS) comes to predict the shock, and elicits an eyeblink conditioned response (CR). While forebrain regions such as the hippocampus and amygdala also contribute to eyeblink conditioning, the critical circuitry for delay eyeblink conditioning is within the cerebellum and brainstem (Thompson and Steinmetz, 2009). The interpositus nucleus of the cerebellum is a site of CS-US convergence, and a critical site of learning-related plasticity: Interpositus activity models acquisition of the CR (McCormick and Thompson, 1984a, b) and temporary inactivation reversibly prevents learning (Krupa et al., 1993). Therefore, although alterations in many brain regions likely contribute to psychopathology, eyeblink conditioning and the critical cerebellar circuitry provides an ideal model system for exploring the mechanisms of neonatal stress effects on adult learning and memory. Understanding how neonatal stress alters the function of this well-characterized model system may ultimately contribute to our understanding of the role of adverse early experience in the development of psychopathology.

Neonatal maternal separation produces deficits in eyeblink conditioning and increases glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression in the posterior region of the interpositus nucleus in adult male rats (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a). Further, infusion of the GR antagonist mifepristone into the posterior interpositus in adults reverses separation-induced deficits in eyeblink conditioning (Wilber et al., 2010), suggesting that the increased GR expression in the posterior interpositus is responsible for the impaired adult eyeblink conditioning. Similarly, neonatal separation-induced increases in plasma corticosterone are apparent following single and repeated daily maternal separation (Wilber et al., 2007), GR expression is altered by postnatal day (PND) 15 (Wilber and Wellman, 2009b), and perinatal corticosterone exposure influences the development of several brain structures (Balazs and Cotterrell, 1972, Ardelenu and Sterescu, 1978, De Kloet et al., 1988b, Sousa et al., 1998, Roskoden et al., 2005), including the cerebellum (Velazquez and Romano, 1987). Thus, neonatal increases in corticosterone could contribute to the effects of maternal separation on GR expression, and consequently adult learning and memory. Therefore, we assessed the effects of daily corticosterone injections on PND 2-14 on adult eyeblink conditioning and GR expression in the interpositus.

1.2 Materials and Methods

1.2.1 Animals and Treatment

As in previous experiments (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber et al., 2009, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a, b, Wilber et al., 2010), untimed pregnant Long Evans rats (Harlan Indianapolis, IN, N = 11) arrived approximately 1 week before giving birth. Dams were housed individually in standard laboratory cages (48 × 20 × 26 cm), with food and water ad libitum and a 12:12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700h). On PND 2 (day of birth = PND 0), pups were culled to litters of 7-10 while maintaining a male:female ratio of approximately 1:1. All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Bloomington IACUC.

Maternal separation produces a slow rise in plasma corticosterone, with the largest peak in corticosterone concentration occurring nearly 12 h after a 1h separation (Walker, 1991, Wilber et al., 2007). It is not possible to exactly duplicate this complicated profile with exogenous corticosterone; therefore we chose to focus on mimicking the peak corticosterone concentrations that occur in the afternoon and early evening 12h after maternal separation. Thus, as in previous experiments (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber et al., 2009, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a, b, Wilber et al., 2010), litters (4-5 per group) were randomly assigned to either standard animal facilities rearing (n = 8 pups; Control), corticosterone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; n = 14 pups), or vehicle treatment groups (n = 10 pups).

Previous studies have shown that neonatal administration of corticosterone in doses ranging from 1 to 5 mg/kg can produce long-lasting elevations in plasma corticosterone and changes in adult behavior (Van Oers et al., 1998, Roskoden et al., 2005). However, because pilot studies in our laboratory indicated that the 5 mg/kg dose produce extremely large and highly variable plasma corticosterone concentrations, in this study we used a smaller dose, 1 mg/kg. Corticosterone was dissolved in sesame oil and administered at approximately 1mg/kg based on unpublished data from our laboratory on average weight for age. Injection volume did not exceed 0.05 ml and vehicle injected pups received an equivalent volume of sesame oil. Weight data from a separate group of age-matched pups were used in place of daily weighing to minimize handling and time away from the dam. Injections were subcutaneous and occurred at approximately 1800h each day. Prior to injections dams were removed from the home cage, after which pups were placed in a Plexiglas cage (28 × 17 × 12 cm) lined with bedding. As is standard practice in our laboratory (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber et al., 2009, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a, b, Wilber et al., 2010), on PND 28, animals were weaned and housed in same sex/same litter groups of 2-3 until surgery.

Although whole litters were manipulated, eyeblink conditioning and GR expression were examined in males only, because separation-induced changes in eyeblink conditioning and GR expression in the posterior interpositus occur only in males (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009b).

1.2.2 Eyeblink Conditioning

At 12-16 weeks of age, electromyographic (EMG) and stimulating electrodes were implanted. Rats were anesthetized with ip ketamine (74 mg/kg), xylazine (3.7 mg/kg), and acepromazine (0.74 mg/kg) and given sc Rimadyl (5 mg/kg). Rats were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus, and two Teflon-coated stainless steel EMG electrodes (0.075 mm) were implanted in the superior portion of the orbicularis oculi of the left eyelid and routed subdermally to the skull, where they were attached via gold pins to a headstage connector (Plastics One; Roanoke, VA). A ground wire was secured to skull screws and attached via a third gold pin to the headstage. A bipolar stimulating electrode (Plastics One) was implanted subdermally dorsocaudal to the left eye and routed to a separate connector. Finally, the connectors were secured to skull screws with dental acrylic. Skin was sutured around the headstage. Rats were housed individually after surgery and handled three times prior to eyeblink conditioning.

After recovery from surgery (≥ 5 days), rats underwent eyeblink conditioning, which took place in operant boxes inside sound-attenuating chambers (Med-Associates; St. Albans, VT). Rats received one 60-min adaptation session in which EMG signal was recorded during trials in which no stimuli were presented. The next 10 days consisted of daily sessions comprised of 10 blocks of 10 trials, 80% paired (8 paired and 2 CS-alone trials/block), with an average 25 s intertrial interval. All trials consisted of a 350-ms pre-CS period, followed by a 375-ms tone CS (2.8 kHz, 85dB) and a 295-ms post-CS period (trial length 1020 ms). During paired trials, the US (3.0-mA, 25-ms periocular stimulation) co-terminated with the CS, producing a 350-ms interstimulus interval.

Stimulus delivery was controlled by Spike2 software (CED, London, UK). Eyeblink EMG activity was amplified (5000×) and bandpass filtered (100-9000 Hz; Lynx-8 amplifier, Neuralynx; Bozeman, MT), then digitized (1000 Hz), rectified, smoothed (0.01 s), time shifted (0.01 s), acquired, and stored with a Power 1401 625 kHz data acquisition system (CED, London, UK). EMG data were analyzed using a custom program to compute the number of trials in which a CR was detected. The threshold for detecting CRs was set at 7 standard deviations above the mean EMG activity during the pre-CS period. EMG activity during the 100-ms period immediately after CS onset was considered an alpha response to the tone rather than a CR (Green et al., 2002, Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a, Wilber et al., 2010). As an estimate of sensory responsivity, the average amplitude of alpha responses was calculated for each animal for the first 10 tone presentations. Trials with excessive spontaneous eye movement (EMG activity during the 100 ms immediately preceding CS onset) were excluded from analysis (Control, mean = 14.6% ± 1.2 SEM; Vehicle 13.6% ± 1.5; Cort, mean = 13.0% ± 1.3 SEM). The percentage of trials in which a CR was displayed and the average amplified amplitude of each CR (V) were calculated for each animal for each day. To capture potential differences in CR production during early versus late training (i.e., acquisition versus asymptotic CR performance), separate repeated measures ANOVAs were performed for early acquisition (days 1-5) versus late acquisition (days 6-10) Significant ANOVAs were followed up by planned comparisons (Hays, 1994, Maxwell and Delaney, 2003). The use of planned comparisons as opposed to all possible pairwise comparisons in the post-hoc analyses is a more conservative approach, as it reduces the probability of a type I error without necessitating a Bonferroni correction.

1.2.3 GR Immunohistochemistry

After eyeblink conditioning, rats were deeply anesthetized with urethane and transcardially perfused with cold 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were removed, postfixed for 24 h, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Frozen sections were cut coronally at 40 μm on a sliding microtome and collected in 0.01M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). For each brain, 8 to 9 equally spaced sections (approximately 160 μm apart) were collected through the entire interpositus nucleus of the cerebellum. For immunohistochemical labeling of GRs, sections were incubated for 1 h in PBS containing 3% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 to block nonspecific binding. Sections were then incubated for 1 h in 0.2% H2O2 in 50% methanol. After rinsing in PBS, sections were incubated overnight at 4° C in PBS containing 3% normal goat serum (NGS), 0.1% Triton X-100, and a polyclonal antibody to the rat GR (1:3000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA). Sections were rinsed in PBS and then incubated for 30 min in PBS containing 5% NGS and biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA). After rinsing in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBST), sections were incubated for 1 h in PBST with ABC Complex (Vector Laboratories). Staining was visualized using a nickel-intensified DAB reaction (Figure 1). After rinsing, sections were mounted on gelatin-subbed slides, dehydrated, cleared, and coverslipped. Control sections incubated without the primary antibody were generated and demonstrated no staining.

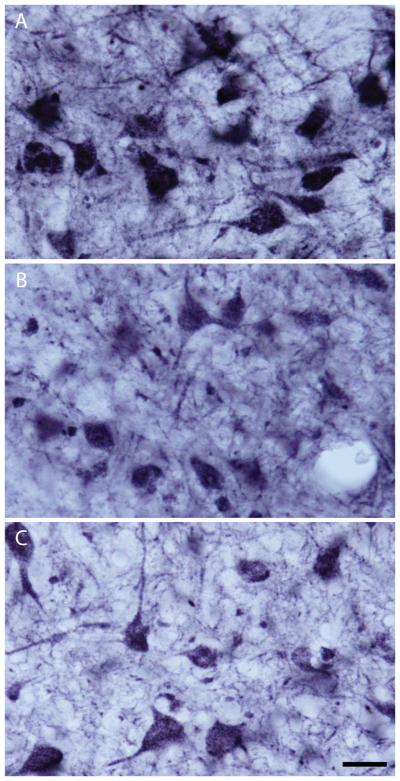

Figure 1.

GR-immunopositive neurons in the posterior interpositus nucleus of representative animals (mean GR staining near the group mean) that underwent standard animal facilities rearing (Control, A), or received daily vehicle (B) or corticosterone injections (C) on PND 2 - 14. Note, illumination was standardized across groups and measures of GR-immunostaining were normalized to background staining (see methods). Scale bar = 25 μm.

1.2.4 Quantification of GR Expression

GR expression in the interpositus nucleus was quantified using a computer-based image analysis system (Neurolucida; MBF Bioscience; Willston, VT) interfaced via a video camera (Microfire; Optronics; Santa Barbara, CA) with a microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon Instruments; Melville, NY). Neurons were sampled from a 100 μm by 125 μm sampling frame at a final magnification of 1440x. The present study explores a potential mechanism of the neonatal separation-induced alterations in interpositus GR expression described in our previous studies (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009b, a, Wilber et al., 2010); therefore, we focused our analysis on the interpositus nucleus of the cerebellum. Sampling frames were centered mediolaterally within the interpositus, and the sampling area size was chosen to yield approximately 15 neurons per frame. All labeled neurons contained within each sampling area were identified based on standard morphological criteria (large, multipolar soma) and the average luminosity per pixel of each soma was measured with values ranging from 0 (black) to 255 (white). To control for spurious differences in staining and illumination across sections and animals: 1) each round of staining contained animals from each group, 2) care was taken to minimize differences in illumination across samples, and 3) luminosity measures within each section were expressed relative to white matter staining. Luminosity was measured in an area of white matter free of visible cell bodies directly above the interpositus averaging 931 μm2. Relative intensity of neuronal staining was then calculated by dividing the luminosity of each neuron by the luminosity of the white matter in that section. Finally, to facilitate data interpretation, each measure was multiplied by 1/x so that larger ratios indicate darker staining (i.e., inverted).

We have previously shown that the separation-induced increase in GR staining is localized to the posterior portion of the interpositus nucleus (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a, b). Therefore, we analyzed data separately from the three most anterior sections (Anterior) and the three most posterior sections (Posterior) of the interpositus nucleus.

Data were analyzed using two different approaches. First, mean relative intensities were compared across interpositus regions (posterior versus anterior) and neonatal treatment conditions using two-way ANOVAs followed by appropriate planned comparisons. Second, to assess potential differences in the distribution of relative staining intensities, 3-bin histograms of the mean number of neurons (expressed as percent of total) categorized as having relative intensities varying from more than 1.0 standard deviation below the mean of controls (low GR expression; light) to within 1.0 standard deviations of the mean of controls (average GR expression; moderate) to greater than 1.0 standard deviations above the mean of controls (high GR expression; dark) were generated. This method has been shown to be reliable for categorizing neurons by immunostaining intensity for subsequent frequency analyses and tends to be more sensitive to differences in protein expression assessed immunohistochemically than are simple means comparisons (Wood et al., 2005, Garrett et al., 2006, Osborne et al., 2007, Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber et al., 2009, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a). Data were compared across groups using repeated measures ANOVAs followed by planned comparisons (two-group F-tests).

1.2.5 Corticosterone Assay

Plasma corticosterone was measured in separate groups of vehicle (n = 11), and corticosterone injected (n = 4) pups 1 h after injection on PND 2. These data were compared to plasma corticosterone data taken from control (n = 10) and separated (1 h/day as described previously; Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber et al., 2009, Wilber and Wellman, 2009b, a, Wilber et al., 2010; n = 17) pups used in a previous study (Wilber et al., 2007). During the first 2 postnatal weeks (stress hyporesponsive period) corticosterone levels peak approximately 12 h after 60 min of maternal separation (Walker, 1991). We previously observed equivalent patterns of corticosterone response on PND 2 and 12 to both maternal separation and handling manipulations, suggesting that corticosterone concentrations measured at PND 2 are representative of the separation-induced corticosterone profile across days. Therefore, we measured corticosterone concentrations on postnatal day 2. The timing of injections in the present study was chosen to coincide with this peak; therefore, blood samples were taken 12 h after the onset of separation and at an approximately equal time of day for control, vehicle, and corticosterone injection groups—5 min after injections. Corticosterone assay procedures were identical for all groups. Pups were rapidly decapitated and trunk blood was collected in heparinized microcapillary tubes and centrifuged at 2000 g for 15 min to obtain plasma. Corticosterone titers were assessed using a competitive enzyme immunoassay kit (Assay Design; Ann Arbor, MI). This assay has low cross-reactivity with other major steroid hormones, sensitivity typically < 27.0 pg/ml, and coefficients of variation within and across assays of 7.7% and 9.7%, respectively. Stress-induced changes in corticosterone concentrations were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (group), with significant values followed up by planned comparisons (two-group F-tests).

1.3 Results

1.3.1 Eyeblink Conditioning

To rule out potential confounds, rate and amplitude of spontaneous blinking during adaptation and responsivity to the tone (alpha response) were compared. Spontaneous blink rate (Figure 2; F(2, 29) = 0.32, ns) and amplitude (Figure 2; F(2, 29) = 0.14, ns) did not vary across neonatal treatment. Similarly, although mean responsiveness to the tone appeared to vary across groups, the effect of neonatal treatment on responsivity to the tone did not approach significance (Data not shown; Control, mean = 0.23 V ± 0.05 SEM; Vehicle 0.12 V ± 0.03; Cort, mean = 0.14 V ± 0.03 SEM; F(2, 29) = 2.06, p = 0.15).

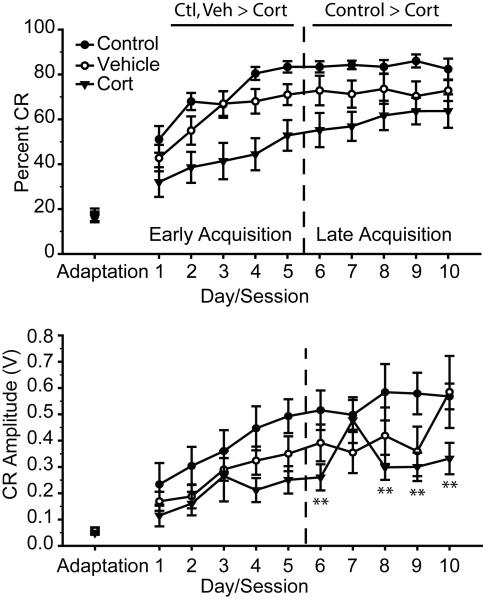

Figure 2.

Above. Mean (± SEM) percentage of conditioned responses (CR) for rats that underwent standard animal facilities rearing (Control, n=8), or received daily vehicle (Vehicle, n=10) or corticosterone injections (Cort, n=14) on PND 2 – 14. Control and vehicle rats performed significantly better than corticosterone-injected rats during early acquisition (Days 1-5, ps < 0.05), and control rats performed significantly better than corticosterone-injected rats during late acquisition (Days 6-10, p ≤ 0.01), while the performance of vehicle treated rats was intermediate (i.e., not significantly different from control or corticosterone-injected rats) during late acquisition. Below. Mean (± SEM) amplitude of CRs for control, vehicle, and corticosterone injected rats. ** p ≤ 0.01 versus Control.

Consistent with our definition for early versus late (post asymptotic) acquisition phases of training, performance improved during early acquisition training, as indicated by increasing percent CR across day (Figure 2; main effect of day, F(4, 116) = 28.76, p < 0.001), but not late acquisition (main effect of day, F(4, 116) = 0.42, ns). There was a significant main effect of neonatal treatment on the percentage of CRs during both early (F(2, 29) = 6.83, p < 0.01) and late acquisition (F(2, 29) = 4.13, p < 0.05). However, there was no day by neonatal treatment interaction for either early or late acquisition (Fs(8, 116) < 0.70, ns); thus, planned comparisons were conducted for early and late acquisition comparing neonatal treatments collapsed across days. During early acquisition, the percentage of conditioned responses did not differ for control and vehicle treated rats (F(1, 16) = 2.71, ns), while rats that received neonatal corticosterone treatment performed significantly worse than both control (F(1, 20) = 11.02, p < 0.01) and vehicle (F(1, 22) = 4.70, p < 0.05) treated rats. During late acquisition, neonatal corticosterone treatment resulted in impaired performance compared to controls (F(1, 20) = 9.18, p ≤ 0.01). Conditioned responding for vehicle treated rats did not differ significantly from either control (F(1, 16) = 3.09, ns) or corticosterone-treated rats (F(1, 22) = 1.34, ns) during late acquisition. Thus, neonatal corticosterone treatment impaired conditioned responding across all phases of training, while performance in vehicle-treated rats was intermediate to that of controls and corticosterone-treated rats.

CR amplitude increased during early acquisition, (Figure 2; main effect of day, F(4, 116) = 14.98, p < 0.001), but not late acquisition (main effect of day, F(4, 116) = 2.13, ns). There was not a significant main effect of neonatal treatment on CR amplitude for either early or late acquisition (Fs(2, 29) < 2.46, ns). However, there was a day by neonatal treatment interaction for late (F(8, 116) = 3.25, p < 0.01), but not early acquisition (F(8, 116) = 1.01, ns). Therefore, planned comparisons were conducted comparing neonatal treatments for each day of late acquisition. Consistent with percent CR analyses, CR amplitude for vehicle-treated rats was intermediate, and not significantly different from control (Fs(1, 16) < 2.99, ns) or corticosterone treated rats (Fs(1, 22) < 3.52, ns). However, compared to control treatment, neonatal corticosterone treatment significantly decreased CR amplitude on acquisition days 6 and 8-10 (Fs(1, 20) > 7.26, p ≤ 0.01; day 7, F(1, 20) = 0.03, ns). Thus, consistent with percent CR data, neonatal corticosterone treatment significantly reduced CR amplitude compared to controls, while vehicle treatment resulted in a mild but non-significant impairment.

1.3.2 GR Expression

Overall, mean (±SEM) intensity of the white matter samples in the interpositus nucleus was 4.9 × 10−3 ± 0.0314 × 10−3, and white matter intensities did not vary across neonatal treatment for the posterior (Data not shown; F(2, 29) = 0.46, ns) or anterior interpositus (Data not shown; F(2, 29) = 0.28, ns). The mean number of neurons measured per section was 15.33 ± 0.65 and did not differ across neonatal treatment for either posterior (Data not shown; F(2, 29) = 2.85, ns) or anterior interpositus (Data not shown; F(2, 29) = 1.65, ns). The average number of neurons measured per animal was 78.31 ± 4.30 and did not differ across neonatal treatment for either posterior (Data not shown; F(2, 29) = 1.52, ns) or anterior interpositus (Data not shown; F(2, 29) = 0.72, ns).

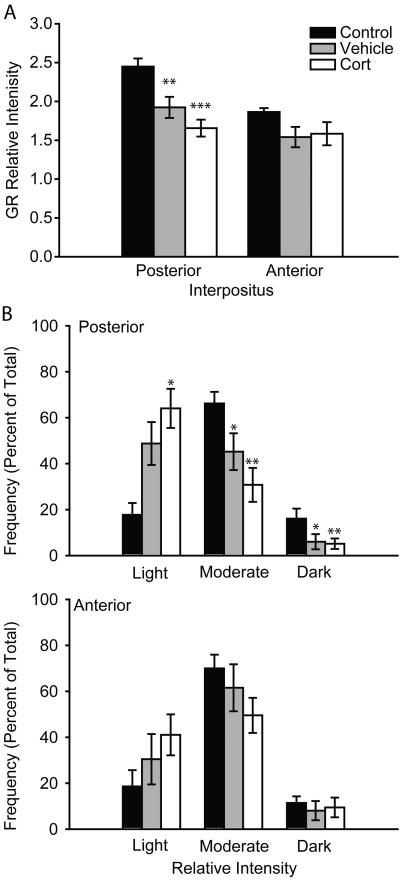

Overall, the mean relative intensity of GR staining varied significantly across neonatal treatment (Figure 3; main effect of neonatal treatment, F(2, 29) = 5.67, p ≤ 0.01) and brain region (posterior versus anterior interpositus; main effect of region, F(1, 29) = 21.81, p < 0.001), and there was a significant brain region by neonatal treatment interaction (F(2, 29) = 4.32, p < 0.05). The mean relative intensity of GR staining varied significantly across neonatal treatment within the posterior (F(2, 29) = 10.49, p < 0.001) but not anterior interpositus (F(2, 29) = 1.38, ns). Therefore, planned comparisons were conducted comparing mean GR expression in the posterior interpositus across neonatal treatments and indicated that both vehicle (F(1, 16) = 8.69, p ≤ 0.01) and corticosterone (F(1, 20) = 23.12, p < 0.001) neonatal treatments had significantly reduced adult GR expression relative to control rats, while GR expression did not significantly differ between corticosterone and vehicle treated rats (F(1, 22) = 2.40, ns). Thus, changes in GR expression in the posterior interpositus nucleus paralleled eyeblink conditioning performance, with the largest change in GR expression in corticosterone-treated rats and a smaller change in GR expression in vehicle-treated rats.

Figure 3.

A. Mean (± SEM) relative intensity of glucocorticoid receptor staining in the anterior (right) and posterior (left) interpositus nucleus for animals that underwent either standard animal facilities rearing (Control), or received daily vehicle (Vehicle) or corticosterone (Cort) injections on PND 2 – 14. B. Immunostaining of neurons in the posterior (above) and anterior (below) interpositus categorized as light (having a relative intensity of one standard deviation below the mean of controls), moderate (within one standard deviation of the mean), or dark (greater than one standard deviation above the mean) for animals that underwent either standard animal facilities rearing (Control), or received daily vehicle (Vehicle) or corticosterone injections (Cort) on PND 2 – 14. * p ≤ 0.05 versus control. ** p < 0.01 versus control. *** p < 0.001 versus control.

Differences in the distribution of GR staining intensities (Figure 3) paralleled those seen in the more gross measure of mean relative intensity (above). As with the mean GR analyses, the effect of neonatal treatment on distribution of GR staining intensities was confined to the posterior region of the interpositus (neonatal treatment × bin interaction, F(4, 58) = 18.35, p < 0.001), with no neonatal treatment differences in GR staining observed in the anterior region (neonatal treatment × bin interaction, F(4, 58) = 1.29, ns). Therefore, for the posterior interpositus, planned comparisons were conducted comparing across neonatal treatments for each intensity bin. Neonatal corticosterone treatment significantly decreased the frequency of darkly and moderately stained neurons (Fs(1, 20) > 11.27, p < 0.01), and significantly increased the frequency of lightly stained neurons (F(1, 20) = 6.02, p < 0.05). A similar but smaller shift towards less intensely stained neurons was apparent in vehicle-treated rats, with a decrease in the frequency of darkly and moderately stained neurons (Fs(1, 16) > 4.37, p ≤ 0.05), but no change in the frequency of lightly stained neurons (F(1, 16) = 3.51, ns). Vehicle- and corticosterone-treated groups did not significantly differ in the frequency of lightly, moderately, or darkly stained neurons (Fs(1, 22) < 1.71, ns). Thus, consistent with the more gross measure of mean relative intensity, changes in GR expression in the posterior interpositus nucleus paralleled eyeblink conditioning performance with the largest reduction in intensely stained neurons in corticosterone-treated rats and a smaller reduction in intensely stained neurons in vehicle treated rats.

1.3.3 GR-Eyeblink Conditioning Correlation

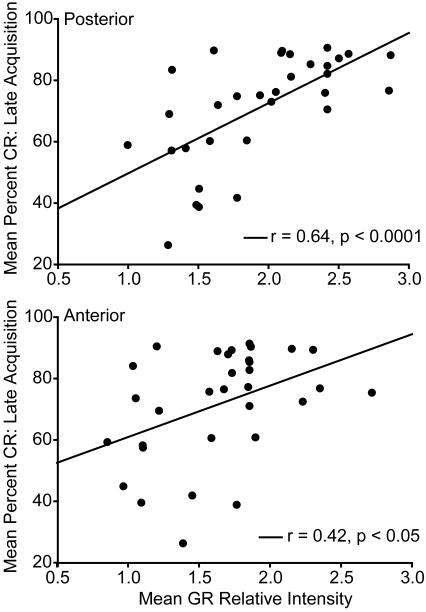

The relationship between average relative intensity of GR staining in the posterior and anterior interpositus and eyeblink conditioning averaged across late acquisition days (day 6 - 10) was examined across all groups. For the posterior interpositus, there was a strong and significant positive correlation between GR staining and percent CR (Fig. 4; r = 0.64, p < 0.001). In addition, anterior interpositus GR immunostaining was less strongly but significantly correlated with average percent CR for late acquisition (Fig. 4; r = 0.42, p < 0.05). Thus, following neonatal corticosterone or vehicle treatment, GR expression in both the anterior and posterior interpositus nucleus predicts eyeblink performance.

Figure 4.

Linear regression analysis for mean (± SEM) GR relative intensity in the posterior (above) and anterior interpositus (below) and percent CR for eyeblink conditioning during late acquisition (day 6 – 10) for animals that underwent either standard animal facilities rearing, or received daily vehicle or corticosterone injections on PND 2 – 14.

1.3.4 Effect of Neonatal Treatment on Neonatal Plasma Corticosterone Concentration

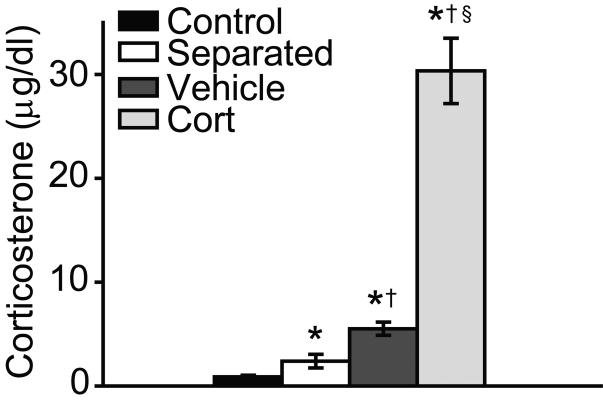

Neonatal corticosterone treatment and vehicle injections decreased GR expression, an effect that is opposite the increased GR expression that occurs following maternal separation (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009b, a). To test the hypothesis that this dissociation might be driven by a difference in the magnitude of the corticosterone response to neonatal injections compared to maternal separation, plasma corticosterone concentrations on PND 2 were compared for control pups and pups that had undergone a single separation, vehicle injection, or corticosterone injection treatment. There was a significant effect of neonatal treatment on plasma corticosterone concentration (Fig. 5; F(3, 28) = 138.06, p < 0.001). Planned comparisons revealed that corticosterone concentrations were elevated relative to controls for all neonatal treatments (Fs(1, 12-33) > 6.95, p < 0.05). Further, vehicle injections increased plasma corticosterone concentrations significantly more than did neonatal separation (F(1, 16) = 10.64, p < 0.01), and corticosterone injection increased plasma corticosterone significantly more than did either neonatal separation or vehicle injection (Fs(1, 9-13) > 130.72, p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Mean (± SEM) corticosterone (μg/dl) sampled at approximately 1800h on PND 2 for animals that underwent either standard animal facilities rearing (Control), 1 h of maternal separation (Separated), received a vehicle (Vehicle), or corticosterone injection (Cort). Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences relative to controls; daggers (†) indicate significant differences relative to separated; section signs (§) indicate significant difference relative to vehicle injected.

1.4 Discussion

Neonatal vehicle injections increased plasma corticosterone concentrations more than neonatal separation, while neonatal corticosterone dose used in the present study produced even greater increases. A similar graded effect of vehicle and corticosterone treatments was apparent on adult eyeblink conditioning, in which neonatal corticosterone injections significantly impaired eyeblink conditioning performance throughout training, whereas rats that received daily vehicle injections had eyeblink conditioning performance intermediate to controls and corticosterone-treated rats. Similarly, daily neonatal vehicle and corticosterone injections both significantly decreased GR expression in the posterior interpositus nucleus, with the largest decrease in GR expression in the corticosterone-treated animals. Finally, there was a significant positive correlation between eyeblink conditioning performance and GR expression in the posterior interpositus. Surprisingly, there was also a significant, though less robust, correlation between eyeblink conditioning performance and GR expression in the anterior interpositus.

The differential effect of neonatal treatment across anterior versus posterior interpositus was consistent with neonatal separation effects on posterior but not anterior interpositus we observed in our previous studies, and provides further support for differential vulnerability of the posterior interpositus to neonatal stress and/or glucocorticoids (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009a, b). The finding of impaired adult learning following neonatal corticosterone exposure is consistent with other studies showing altered hippocampally mediated learning following neonatal exposure to elevated corticosterone (Claflin et al., 2005, Roskoden et al., 2005). Similarly, neonatal separation-induced increases in plasma corticosterone concentration have been associated with impaired spatial learning and memory (Huot et al., 2002), eyeblink conditioning (Wilber et al., 2007), and extinction of conditioned fear (Wilber et al., 2009). However, the timing or route of administration for neonatal corticosterone exposure may be critical, because corticosterone administration at a later time point (PND 18-21) did not significantly impair delay eyeblink conditioning (Claflin et al., 2005).

We have previously shown that neonatal separation produces adult impairments in eyeblink conditioning that are correlated with increased GR expression (Wilber et al., 2007). In the present study, we demonstrated that neonatal vehicle and corticosterone injections result in graded impairments in eyeblink conditioning and decreases in posterior interpositus GR expression. Thus, neonatal separation, vehicle injections, and corticosterone injections all impair eyeblink conditioning but have opposite effects on adult GR expression in the posterior interpositus. The pattern of results from these studies suggests that either too much or too little GR expression in the interpositus can impair eyeblink conditioning performance. Consistent with this hypothesis, GR antagonism in the posterior interpositus reverses separation-induced deficits but impairs performance in control rats (Wilber et al., 2010). Future studies can directly test this hypothesis by assessing the effects of GR agonists in the posterior interpositus on adult eyeblink conditioning in neonatally injected rats.

Regardless, the opposite effects of neonatal separation and neonatal injections on adult GR expression are surprising given that neonatal separation, vehicle injections, and corticosterone injections produce successively larger increases in neonatal plasma corticosterone concentrations (i.e., linear relationship). The differential effect of separation versus vehicle administration on adult GR expression is especially surprising given that the differences in neonatal plasma corticosterone concentrations are small for neonatal separation versus neonatal vehicle injections. However, our manipulations were performed during the stress hyporesponsive period (originally termed the stress non-responsive period) when the basal and stress response levels of corticosterone are markedly reduced or absent (De Kloet et al., 1988a, Walker, 1991, Leal et al., 1999, Zilz et al., 1999), and the differential increase in corticosterone in separated versus vehicle-injected pups was small but significant. These data suggest that corticosterone's regulation of GR expression during this period operates within a very narrow range, and thus even small variations in neonatal corticosterone may have profound effects on GR expression. Futher, our data suggest that an inverted U-shaped relationship may exist between neonatal corticosterone levels and adult GR expression, in which modest increases in corticosterone (neonatal separation) increase adult GR expression but larger increases (neonatal injections) decrease adult GR expression.

The possibility of an inverted U-shaped function exists for neonatal corticosterone concentration and adult cerebellar GR expression and consequently cerebellar dependent learning is consistent with previous studies showing an inverted U-shaped relationship between GR activation and consolidation of passive avoidance learning in adults (Roozendaal and McGaugh, 1997, Roozendaal et al., 2009). Further, either too much or too little corticosterone has adverse consequences for both the adult and developing brain. For example, adult glucocorticoid administration (Woolley et al., 1990) and adrenalectomy (Gould et al., 1990) both result in denditric atrophy in the hippocampus. Similarly, adrenalectomy in the third postnatal week increased pyknosis in the hippocampus including the dentate gyrus (Gould et al., 1991). Finally, hydrocortisone injections during the first postnatal week reduce the number of cerebellar and hippocampal granular cells (Bohn and Lauder, 1978, Bohn, 1979, 1980).

Alternatively, it is possible that some other aspect of the type of neonatal treatment (injection versus separation) and not the corticosterone levels produced by these treatments are responsible for the effects we observed. For example, the effects we observed may be due to treatment-induced alterations in neonatal maternal care and not neonatal plasma corticosterone levels. Long neonatal maternal separation and brief separation may have opposite effects on maternal care (Pryce et al., 2001), and have opposite effects on adult GR expression (Meaney et al., 1989, Liu et al., 1997, Ladd et al., 2004). Thus, differential alterations in maternal care in separated versus injected pups could contribute to the opposite effect of maternal separation and neonatal injections on adult interpositus GR expression that we observed, since administration of neonatal injections requires a brief separation from the dam. However, both long (1 h) and brief (15 min) separation increase GR expression in the posterior interpositus (Wilber et al., 2007), so differences in maternal care between our separated and injected pups are not likely to be directly responsible for the effects we observed.

It is possible that our neonatal manipulation altered arousal, since blink amplitude to the first few tone presentations was lower, though non-significantly (p=0.15), in neonatally injected rats. However, others have shown that repeated postnatal dexamethasone administration does not alter adult basal HPA axis activity (Felszeghy et al., 1996, Felszeghy et al., 2000). Further, here we show a significant change in GR expression in the interpositus nucleus, a significant correlation between interpositus GR expression and eyeblink conditioning, and we previously demonstrated that changes in GR activation in the interpositus can impair eyeblink conditioning (Wilber et al., 2010). Together, these data suggest that interpositus GR expression and not arousal was most likely responsible for the effects we observed.

Further, an alternative explanation for our data is that the observed changes in cerebellar GR expression are an interactive effect of neonatal treatment and the stress of adult surgery and behavioral testing. However, this is unlikely, as we have previously shown that neonatal separation alters GR expression in rats that have not been subjected to surgery or eyeblink conditioning (Wilber and Wellman, 2009b).

Previously, we reported that neonatal separation-induced increased GR expression and correlated deficits in eyeblink conditioning were confined to the posterior interpositus and absent in the anterior interpositus (Wilber et al., 2007, Wilber and Wellman, 2009b, a). However, in the present study, in addition to the robust changes in posterior interpositus GR expression and correlated eyeblink conditioning performance, we also found a weak (r = 0.42) but significant correlation between anterior interpositus GR expression and eyeblink conditioning performance. The significantly larger increase in neonatal plasma corticosterone following injection manipulations versus maternal separation observed in the present study may suggest that the anterior interpositus is less sensitive but not immune to the effects of neonatal stress. There is evidence for topographical (i.e., anterior to posterior) organization of the circuitry important for learning (Steinmetz et al., 1992a, Steinmetz et al., 1992b, Plakke et al., 2007) and modulating (Delgado-Garcia and Gruart, 2006, Sanchez-Campusano et al., 2007, 2009) the eyeblink CR, and there are developmental differences in GR receptor expression in anterior versus posterior interpositus (Wilber and Wellman, 2009b). Thus, the more robust effect on posterior interpositus may result from differences in the timing of the development of GR receptors in anterior versus posterior interpositus.

In summary, neonatal corticosterone injections resulted in impaired adult eyeblink conditioning and decreased GR expression in the posterior interpositus nucleus, and lower GR expression in both posterior and anterior interpositus was associated with impaired learning. Maternal separation, neonatal vehicle injections, and neonatal corticosterone injections produced successively larger increases in neonatal plasma corticosterone; however, while neonatal injections and maternal separation both produce adult impairments in learning and memory, these manipulations produce opposite changes in GR expression. Thus, there may be an inverted U-shaped relationship between both neonatal corticosterone levels and adult GR expression in the interpositus nucleus, and adult GR expression in the interpositus and eyeblink conditioning.

Finally, we have utilized a simplified and well-characterized model system for exploring the mechanisms of neonatal stress effects on adult learning and memory. The results of our study may be applied to further our understanding of complex psychiatric disorders that are likely the product of multiple etiologies and brain systems. For instance, our results suggest that neonatal perturbations may alter the glucocorticoid system to produce adult disorders with developmental underpinnings such as schizophrenia. For example, perinatal stress is a risk factor for schizophrenia (van Os and Selten, 1998; Edwards, 2007), and eyeblink conditioning is impaired in schizophrenics (Bolbecker et al., 2009). Our data suggest that neonatal alterations in glucocorticoids and resultant cerebellar dysfunction may contribute to this deficit.

Research Highlights.

➢ Vehicle and corticosterone injections produce large increases in corticosterone

➢ Neonatal corticosterone injections impaired adult eyeblink conditioning

➢ Neonatal corticosterone injections decreased GR expression in the interpositus

➢ Neonatal vehicle injections effects were intermediate to control and corticosterone

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by MH085415 to AW and the Indiana METACyt Initiative of Indiana University to CLW, funded in part through a major grant from the Lilly Endowment, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aisa B, Gil-Bea FJ, Marcos B, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Río J, Ramírez MJ. Neonatal stress affects vulnerability of cholinergic neurons and cognition in the rat: Involvement of the HPA axis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1495–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisa B, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Rio J, Ramirez MJ. Cognitive impairment associated to HPA axis hyperactivity after maternal separation in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:256–266. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelenu A, Sterescu N. RNa and DNA synthesis in developing rat brain: hormonal influences. Pychoneuroendocrinology. 1978;3:93–101. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(78)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs R, Cotterrell M. Effect of hormonal state on cell number and functional maturation of the brain. Nature. 1972;236:348–350. doi: 10.1038/236348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MC. The effects of hydrocortisone on postnatal neurogenesis in the rat cerebellum and hippocampus: A morphological and autoradiographic study. University of Conneticut; Storrs: 1979. Ph. D. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MC. Granule cell genesis in the hippocampus of rats treated neonatally with hydrocortisone. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2003–2012. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MC, Lauder JM. The effects of neonatal hydrocortisone on rat cerebellar development. An autoradiographic and light microscopic study. Developmental Neuroscience. 1978;1:250–264. [Google Scholar]

- Claflin DI, Hennessy MB, Jensen SJ. Sex-specific effects of corticosterone on hippocampally mediated learning in young rats. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;85:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes AM, Saltzman KM, Weems CF, Regnault HP, Reiss AL, Carrion VG. Development of anxiety disorders in a traumatized pediatric population: a preliminary longitudinal evaluation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:905–914. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh R, Geyer M, Olivier B, Groenink L. The effects of sex and neonatal maternal separation on fear-potentiated and light-enhanced startle. Behav Brain Res. 2005;161:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, Rosenfeld P, Van Ekelen AM, Sutanto W, Levine S. Stress, glucorticoids and development. Progress in Brain Research. 1988a;73:101–120. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, Rosenfeld P, Van Ekelen AM, Sutanto W, Levine S. Stress, glucorticoids and development. In: Boer GJ, et al., editors. Prog Brain Res. Vol. 73. Elsevier Science Publishers B. V.; 1988b. pp. 101–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Garcia JM, Gruart A. Building new motor responses: eyelid conditioning revisited. Trends in Neurosciences. 2006;29:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MJ. Hyperthermia in utero due to maternal influenza is an environmental risk factor for schizophrenia. Congenital Anomalies. 2007;47:84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2007.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felszeghy K, Bagdy G, Nyakas C. Blunted Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response in Adult Rats Following Neonatal Dexamethasone Treatment. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2000;12:1014–1021. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felszeghy K, Gaspar E, Nyakas C. Long-Term Selective Down-Regulation of Brain Glucocorticoid Receptors after Neonatal Dexamethasone Treatment in Rats. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1996;8:493–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.04822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett JE, Kim I, Wilson RE, Wellman CL. Effect of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blockade on plasticity of frontal cortex after cholinergic deafferentation in rat. Neuroscience. 2006;140:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glod CA, Teicher MH. Relationship between early abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and activity levels in prepubertal children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1384–1393. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Short-term glucocorticoid manipulations affect neuronal morphology and survival in the adult dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1990;37:367–375. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90407-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Adrenal steroids regulate postnatal development of the rat dentate gyrus: I. Effects of glucocorticoids on cell death. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1991;313:479–485. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JT, Johnson TB, Goodlett CR, Steinmetz JE. Eyeblink classical conditioning and interpositus nucleus activity are disrupted in adult rats exposed to ethanol as neonates. Learning & Memory. 2002;9:304–320. doi: 10.1101/lm.47602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays WL. Statistics. Harcourt Brace; Fort Worth, TX: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huot RL, Plotsky PM, Lenox RH, McNamara RK. Neonatal maternal separation reduces hippocampal mossy fiber density in adult Long Evans rats. Brain Research. 2002;950:52–63. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02985-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichev M, Easterling KW, Plotsky PM, Holtzman SG. Long-lasting changes in stress-induced corticosterone response and anxiety-like behaviors as a consequence of neonatal maternal separation in Long-Evans rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;73:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupa DJ, Thompson JK, Thompson RF. Localization of a Memory Trace in the Mammalian Brain. Science. 1993;260:989–991. doi: 10.1126/science.8493536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd CO, Huot RL, Thrivikraman KV, Nemeroff CB, Meaney MJ, Plotsky PM. Long-Term adaptations in glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor mRNA and negative feedback on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis following neonatal maternal separation. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Ognibene E, Romano E, Adriani W, Keller F. Gene-environment interaction during early development in the heterozygous reeler mouse: Clues for modelling of major neurobehavioral syndromes. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal ÃnMO, Carvalho J, Moreira AC. Ontogenetic Diurnal Variation of Adrenal Responsiveness to ACTH and Stress in Rats. Hormone Research. 1999;52:25–29. doi: 10.1159/000023428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Science. 1997;277:1659–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizardi H, Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Risco LP, Anderson RL, Donaldson SK. Reports of the childhood home environment in early-onset dysthymia and episodic major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:132–139. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Gallardo M, Llorente R, Llorente-Berzal A, Marco EM, Prada C, Di Marzo V, Viveros MP. Neuronal and glial alterations in the cerebellar cortex of maternally deprived rats: Gender differences and modulatory effects of two inhibitors of endocannabinoid inactivation. Developmental Neurobiology. 2008;68:1429–1440. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Delaney HD. Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, New Jersey: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Thompson RF. Cerebellum: Essential involvement in the clasically conditioned eyeblink response. Science. 1984a;223:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.6701513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Thompson RF. Neuronal responses of the rabbit cerebellum during acquisition and performance of a classically conditioned nictitating membrane-eyelid response. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1984b;4:2811–2822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02811.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J, Anisman H, Merali Z. Short-and long-periods of neonatal maternal separation differentially effect anxiety and feeding in adult rats: gender-dependent effects. Brain Research: Developmental Brain Research. 1999;113:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Aitken DH, Viau V, Sharma S, Sarrieau A. Neonatal handling alters adrenocortical negative feedback sensitivity and hippocampal type II glucocorticoid receptor binding in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;50:597–604. doi: 10.1159/000125287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne MC, Verhovshek T, Sengelaub DR. Androgen regulates trkB Immunolabeling in spinal motoneurons. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2007;85:303–309. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plakke B, Freeman JH, Poremba A. Metabolic mapping of the rat cerebellum during delay and trace eyeblink conditioning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2007;88:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryce CR, Bettschen D, Feldon J. Comparison of the effects of early handling and early deprivation on maternal care in the rat. Developmental Psychobiology. 2001;38:239–251. doi: 10.1002/dev.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid receptor agonist and antagonist administration into the basolateral but not central amygdala modulates memory storage. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 1997;67:176–179. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McReynolds JR, Van der Zee EA, Lee S, McGaugh JL, McIntyre CK. Glucocorticoid Effects on Memory Consolidation Depend on Functional Interactions between the Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Basolateral Amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:14299–14308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3626-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoden T, Linke R, Schwegler H. Transient early postnatal corticosterone treatment of rats leads to accelerated aquisition of a spatial radial maze task and morphological changes in the septohippocampal region. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salk L, Lipsitt LP, Sturner WQ, Reilly BM, Levat RH. Relationship of maternal and perinatal conditions to eventual adolescent suicide. Lancet. 1985;1:624–627. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Campusano R, Gruart A, Delgado-Garcia JM. The Cerebellar Interpositus Nucleus and the Dynamic Control of Learned Motor Responses. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6620–6632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0488-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Campusano R, Gruart A, Delgado-Garcia JM. Dynamic Associations in the Cerebellar-Motoneuron Network during Motor Learning. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10750–10763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäble S, Poeggel G, Braun K, Gruss M. Long-term consequences of early experience on adult avoidance learning in female rats: Role of the dopaminergic system. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2007;87:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa N, Madeira MD, Paula-Barbosa MM. Effects of corticosterone treatment and rehabilitation on the hippocampal formation of neonatal and adult rats. An unbiased stereological study. Brain Research. 1998;794:199–210. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz JE, Lavond DG, Ivkovich D, Logan CG, Thompson RF. Disruption of classical eyelid conditioning after cerebellar lesions: damage to a memory trace system or a simple performance deficit? J Neurosci. 1992a;12:4403–4426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04403.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz JE, Logue SF, Steinmetz SS. Rabbit classically conditioned eyelid responses do not reappear after interpositus nucleus lesion and extensive post-lesion training. Behav Brain Res. 1992b;51:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson CW, Spicer CH, Mason R, Marsden CA. Early life programming of fear conditioning and extinction in adult male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;205:505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RF, Steinmetz JE. The role of the cerebellum in classical conditioning of discrete behavioral responses. Neuroscience. 2009;162:732–755. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uysal N, Ozdemir D, Dayi A, Yalaz G, Baltaci AK, Bediz CS. Effects of maternal deprivation on melatonin production and cognition in adolescent male and female rats. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 2005;26:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oers HJJ, De Kloet ER, Li C, Levine S. The ontogeny of glucocorticoid negative feedback: Influence of maternal deprivation. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2838–2846. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os J, Selten JP. Prenatal exposure to maternal stress and subsequent schizophrenia. The May 1940 invasion of The Netherlands.[see comment] British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:324–326. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.4.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez PN, Romano MC. Corticosterone therapy during gestation: effects on the development of rat cerebellum. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 1987;5:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(87)90029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C-D, Scribner KA, Cascio CS, Dallman MF. The pituitary-adrenocortical system of neonatal rats is responsive to stress throughout development in a time-dependent and stressor-specific fashion. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1385–1395. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-3-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber AA, Lin GL, Wellman CL. Glucocorticoid receptor blockade in the posterior interpositus nucleus reverses maternal separation-induced deficits in adult eyeblink conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;94:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber AA, Southwood C, Sokoloff G, Steinmetz JE, Wellman CL. Neonatal maternal separation alters adult eyeblink conditioning and glucocorticoid receptor expression in the interpositus nucleus of the cerebellum. Developmental Neurobiology. 2007;67:1751–1764. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber AA, Southwood CJ, Wellman CL. Brief Neonatal Maternal Separation Alters Extinction of Conditioned Fear and Corticolimbic Glucocorticoid and NMDA Receptor Expression in Adult Rats. Developmental Neurobiology. 2009;69:73–87. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber AA, Wellman CL. Neonatal maternal separation-induced changes in glucocorticoid receptor expression in posterior interpositus interneurons but not projection neurons predict deficits in adult eyeblink conditioning. Neuroscience Letters. 2009a;460:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber AA, Wellman CL. Neonatal maternal separation alters the development of glucocorticoid receptor expression in the interpositus nucleus of the cerebellum. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2009b;27:649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood DA, Buse JE, Wellman CL, Rebec GV. Differential environmental exposure alters NMDA but not AMPA receptor subunit expression in nucleus accumbens core and shell. Brain Research. 2005;1042:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Gould E, McEwen BS. Exposure to excess glucocorticoids alters dendritic morphology of adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Brain Research. 1990;531:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90778-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilz A, Li H, Castello R, Papadopoulos V, Widmaier EP. Developmental Expression of the Peripheral-Type Benzodiazepine Receptor and the Advent of Steroidogenesis in Rat Adrenal Glands. Endocrinology. 1999;140:859–864. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]