Abstract

Based on the concept that anticocaine antibodies could prevent inhaled cocaine from reaching its target receptors in the brain, an effective anticocaine vaccine could help reverse cocaine addiction. Leveraging the knowledge that E1−E3− adenovirus (Ad) gene transfer vectors are potent immunogens, we have developed a novel vaccine platform for addictive drugs by covalently linking a cocaine analog to the capsid proteins of noninfectious, disrupted Ad vector. The Ad-based anticocaine vaccine evokes high-titer anticocaine antibodies in mice sufficient to completely reverse, on a persistent basis, the hyperlocomotor activity induced by intravenous administration of cocaine.

Introduction

Addiction to opiates, nicotine, and other small molecule addictive drugs is a major worldwide problem for which there are few effective therapies.1,2,3 Based on the concept that high titers of addictive drug-specific antibodies would bind to the addictive drug in blood, therefore preventing it from reaching its cognate receptors in the brain, the development of antiaddictive drug vaccines is one approach to addiction therapy.2,3 Prior vaccine strategies against addictive drugs include linking analogs of addictive small molecules as haptens to macromolecules such as keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), cholera toxin, and tetanus toxin.4,5,6,7 Although these approaches have had some success, the limiting factor is the degree of immunity evoked by the addictive drug analog linked to the macromolecule carrier.1,6,8

In the present study, we demonstrate a novel platform strategy for the development of immunity to addictive drugs based on the knowledge that adenovirus (Ad) gene transfer vectors act as potent immunogens.9,10 We hypothesized that covalently linking the addictive drug or its analog to Ad-capsid proteins would elicit high-titer antibodies against the addictive drug sufficient to sequester a systemically administered addictive drug from access to the brain, thus suppressing the characteristic drug induced behavior. To achieve this, we used an E1−E3− Ad gene transfer vector as the starting material, circumventing possible toxicity mediated by Ad E1 gene products or immunosuppression by Ad E3 proteins.11 Finally, we strategized that we could further circumvent any risk of using an infectious virus by disrupting the E1−E3− Ad, with the hypothesis that a vaccine comprised of an addictive drug coupled to disrupted E1−E3− Ad-capsid proteins would retain the immunologic adjuvant properties of an infectious Ad, and the immune system would evoke high-titer antidrug antibodies sufficient to function as an antiaddictive vaccine.

Results

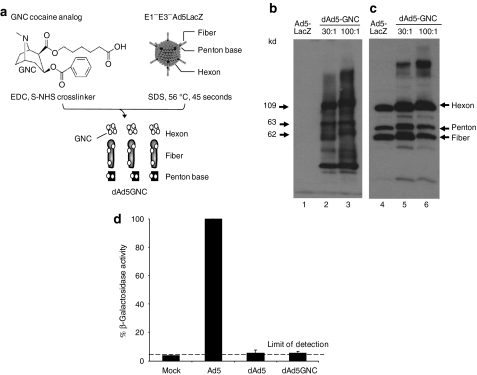

As a model system to assess these hypotheses, an anticocaine vaccine (dAd5GNC) was created by covalently conjugating the cocaine analog GNC (6-(2R,3S)-3-(benzoyloxy)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo [3.2.1] octane-2-carbonyloxy-hexanoic acid) to a disrupted serotype 5 E1−E3− Ad gene transfer vector (Figure 1a).4 The GNC analog was used instead of cocaine per se because it optimizes the structure as a hapten for immune responses.4 The cocaine analogue is designed such that chemical coupling to the Ad proteins minimizes the formation of noncocaine-like structures, yet maintains the antigenic determinant of the cocaine moiety.4 Western analysis of the conjugate of the cocaine hapten to the disrupted Ad at two GNC to Ad capsomere ratios, 30:1 and 100:1, indicated that the GNC content was greater at the 100:1 ratio (Figure 1b). Additional increases to the GNC hapten to Ad capsomere ratios showed no further increase in conjugation levels (data not shown). The anti-Ad immunity of the vaccine was robust, independent of ratio of GNC to the Ad (Figure 1c). Based on this data, the dAd5GNC vaccine created with the GNC to Ad ratio of 100:1 was selected for subsequent experiments. To demonstrate that the dAd5GNC vaccine was not infectious, the ability of the vaccine to express the β-galactosidase transgene was assessed after culture with A549 cells. Whereas the nonconjugated, nondisrupted E1−E3− Ad5LacZ vector was capable of mediating expression of the β-galactosidase transgene, neither the nonconjugated disrupted Ad5LacZ vector nor the dAd5GNC vaccine per se were capable of mediating β-galactosidase expression, and therefore, were noninfectious (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Conjugation of the cocaine analog GNC to disrupted E1−E3− Ad5. (a) Schematic of the steps for conjugating the dAd5GNC vaccine. The E1−E3−Ad5LacZ gene transfer vector (“Ad5” LacZ = β-galactosidase transgene) was disrupted with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 56 °C, 45 seconds), followed by the covalent linking of GNC to the Ad5 capsid proteins with 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (S-NHS) to create dAd5GNC. (b) Anti-GNC western analysis. Lane 1-Ad5LacZ; lane 2-GNC conjugated disrupted Ad5 (30:1); and lane 3-100:1 ratio. (c) Anti-Ad5 western analysis. Lane 4-unconjugated Ad5LacZ; lane 5-GNC conjugated disrupted Ad5 (30:1 ratio); and lane 6-100:1 ratio. (d) Lack of dAd5GNC infectious capacity assessed by the inability of the dAd5GNC vaccine to mediate expression of its β-galactosidase transgene. A549 cells were exposed to Ad5LacZ (Ad5), disrupted Ad5 (dAd5) or dAd5GNC (ratio 100:1). β-galactosidase activity in cell lysate was assessed after 48 hour. GNC, (6-(2R,3S)-3-(benzoyloxy)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo [3.2.1] octane-2-carbonyloxy-hexanoic acid).

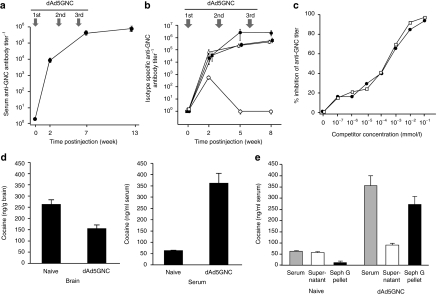

When the dAd5GNC vaccine was administered to BALB/c mice (4 µg at 0, 3, and 6 week), anti-GNC enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titers were elicited with mean reciprocal titers of 7.2 × 105 ± 1.8 × 105 by 13 weeks (Figure 2a). Quantification of the time course of isotype-specific titers revealed an initial anti-GNC immunoglobulin M (IgM) specific titer that fell below detection levels by 5 weeks. Anti-GNC IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b titers were detectable at week 2 and steadily increased (Figure 2b). A competitive ELISA demonstrated that the elicited antibodies recognized a moiety common to both cocaine and GNC with equal specificity (Figure 2c). At week 7 after 3rd immunization, the Kd for cocaine was 45 ± 16 nmol/l.12

Figure 2.

dAd5GNC evoked anti-GNC antibodies in mice. (a) Total anti-GNC IgG antibody titers over time. BALB/c mice (n = 20) were vaccinated intramuscularly with 4 µg dAd5GNC at 0, 3, and 6 week. Antibody titers were assessed by ELISA against BSA conjugated-GNC at 0, 2, 7, and 13 week. (b) Immunoglobulin isotypes of anti-GNC antibodies. Sera was evaluated by ELISA using isotype-specific secondary antibodies for IgG1 (closed circles), IgG2a (open triangles), IgG2b (closed squares), and IgM (open circles). For a and b antibody titers are mean values ± SEM. (c) Demonstration that dAd5GNC evoked antibodies are cocaine-specific. Inhibition of binding of dAd5GNC immune sera to BSA-GNC by ELISA in the presence of increasing concentrations of GNC (open squares) or cocaine (closed circles). (d) Levels of cocaine in brain and serum of BALB/c mice challenged with 3H-cocaine in naive and dAd5GNC vaccinated mice. Shown are cocaine levels in the brain (ng/g brain) and serum (ng/ml serum) of naive and immunized mice. Evaluations were at 1 minute following 3H-cocaine challenge in n = 4 mice/group 3 week after the 3rd immunization with dAd5GNC. Comparisons between groups were conducted by one-way paired two sample t-test. (e) Fraction of serum cocaine bound to IgG. 3H-cocaine (2.5 µg) was administered intravenously to BALB/c mice (n = 4). After 1 minute, serum was obtained, mixed with protein G-Sepharose, and assessed for bound 3H-cocaine (i.e., IgG bound) relative to the 3H-cocaine in the supernatant. BSA, bovine serum albumin; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; GNC, (6-(2R,3S)-3-(benzoyloxy)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo [3.2.1] octane-2-carbonyloxy-hexanoic acid).

When 3H-cocaine was administered intravenously to the dAd5GNC mice, the levels in the brain of immunized mice were reduced by 41% compared to naive mice, t = 9.8, P < 0.002 (Figure 2d; comparisons between groups were conducted by one-way paired two sample t-test). Concurrently, the 3H-cocaine levels in the serum in immunized mice was increased by more than fivefold, t = 6.7, P < 0.004, such that there was a 8.8-fold change in the ratio of blood to brain cocaine levels in the immunized mice. Serum collected at 1 minute postinjection and incubated with protein G-Sepharose, demonstrated that 76% of the 3H-cocaine in serum was associated with an IgG antibody in the vaccinated mice (Figure 2e).

To demonstrate that the high anticocaine titers elicited by dAd5GNC could prevent cocaine administered at levels comparable to human doses from inducing hyperlocomotion in mice, naive and dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice were challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 µg) and locomotor activity evaluated in photobeam equipped activity chambers. Naive mice receiving intravenous 25 or 50 µg of cocaine traveled over greater distance than did naive mice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Figure 3a). In contrast, dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice exposed to the same levels of cocaine had activity similar to mice that were challenged with PBS. Quantitative measurement of the cumulative distance traveled plotted on a per minute basis (Figure 3b) demonstrated that naive mice challenged with 50 µg of cocaine exhibited marked cocaine-induced ambulatory activity compared to dAd5GNC mice (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test D = 0.7; P < 0.0001) and PBS controls (D = 0.8; P < 0.0001). Analysis of noncumulative data (using the three-way repeated measures ANOVA) showed similar results (F = 32.9; P < 0.0001). Post-hoc analysis showed that naive mice challenged with cocaine exhibited marked cocaine-induced ambulatory activity compared to all other groups at each time point (Sheffé test; P < 0.0001). Although the dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 50 µg cocaine displayed statistically greater ambulatory activity than the naive PBS control (D = 0.35; P < 0.0005), they had far less locomotor activity than that of naive mice exposed to 50 µg cocaine (D = 0.7; P < 0.0001). More specifically, the naive mice exposed to 50 µg cocaine traveled a significantly greater distance (4.41 ± 0.22 m) than dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 50 µg cocaine (1.51 ± 0.28 m, P < 0.001, Figure 4b). The relative time each mouse spent in ambulatory, stereotypic, vertical, and resting time was measured in naive and vaccinated mice with and without the highest level cocaine challenge, 50 µg (Figure 3c). Pairwise comparisons using the χ2 test for all behavioral activities (stereotypy, ambulatory, rest, vertical) showed that the distribution of these behaviors had marked differences between naive and immunized mice exposed to cocaine (χ2 = 29.1, P < 0.0001). At the same time naive and dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice challenged with PBS had similar distributions (χ2 = 0.53, P > 0.9) that matched the vaccinated mice challenged with cocaine (χ2 = 0.99, P > 0.8, χ2 = 1.6, P > 0.6, respectively). The three groups of mice (naive challenged with PBS; dAd5GNC-vaccinated challenged with PBS; and dAd5GNC-vaccinated challenged with cocaine) showed proportional distributions, all distinct from cocaine-challenged naive mice (χ2 = 32.5.0, P < 0.0001; χ2 = 28.0, P < 0.0001; χ2 = 29.1, P < 0.0001, respectively).

Figure 3.

Locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice following cocaine or PBS challenge. Vaccinated or naive mice (n = 15 per group) were challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 µg) or PBS and locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus. (a) Visual tracings of the locomotor activity of (three independent examples of each): 1st column-naive mice challenge with PBS; 2nd-naive mice, 25 µg cocaine; 3rd-dAd5GNC vaccinated mice, 25 µg cocaine; 4th-naive mice, 50 µg cocaine; and 5th-dAd5GNC vaccinated mice, 50 µg cocaine. Additional visual tracings are presented in Supplementary Figure S2. (b) Cumulative ambulatory time of naive and dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice as a function of time after challenge with PBS or 50 µg cocaine. dAd5GNC + PBS (open triangles; control) versus naive + PBS (closed squares; control), D = 0.18, P > 0.14; naive + cocaine (closed circles) versus both controls, dAd5GNC + PBS, D = 0.8, P < 0.0001 and naive + PBS, D = 0.9, P < 0.0001; naive + cocaine versus dAd5GNC + cocaine (open circles), D = 0.7, P < 0.0001; dAd5GNC + cocaine versus both controls, naive + PBS, D = 0.35, P < 0.0005, and dAd5GNC + PBS, D = 0.21, P < 0.0005; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (c) Distribution of locomotor activities. Percent of time spent in ambulatory, vertical, stereotypic activity and at rest of naive or dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with PBS or 50 µg cocaine (4 weeks after the 3rd immunization). dAd5GNC + PBS (control) versus naive + PBS (control) χ2 = 0.53, P > 0.9; naive + cocaine versus both controls, dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 28.0, P < 0.0001 and naive + PBS, (χ2 = 32.5, P < 0.0001; naive + cocaine versus dAd5GNC + cocaine, (χ2 = 29.1, P < 0.0001); dAd5GNC + cocaine versus both controls, naive + PBS, χ2 = 0.99, P > 0.8, and dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 1.6, P > 0.6; χ2 test. Additional visual representations of Figure 3c are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. For all panels, all studies carried out in the 27 cm × 27 cm Med Associates chamber (see Materials and Methods section). Ad, adenovirus; GNC, (6-(2R,3S)-3-(benzoyloxy)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo [3.2.1] octane-2-carbonyloxy-hexanoic acid); PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

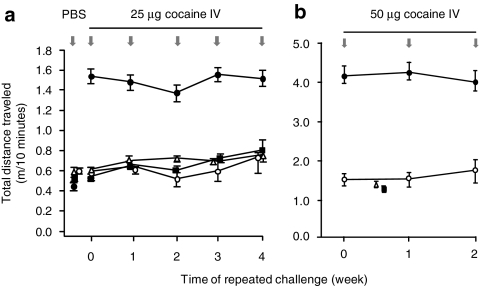

Figure 4.

Persistence of dAd5GNC vaccine-evoked immunity. Comparison of naive and dAd5GNC immunized mice (n = 15 per group) as assessed by cocaine-induced locomotor activity upon repeated exposures at two different cocaine challenge doses. (a) Total distance traveled in 10 minutes immediately following PBS or cocaine (25 µg) challenge plotted for each sequential weekly trial (n = 15/group). In addition, all four experimental groups were initially injected with PBS to establish baseline activity (this is shown by nonconnected symbols along the y axis). dAd5GNC + cocaine (open circles) versus naive + cocaine (closed circles), F = 40.9, P < 0.0005; dAd5GNC + cocaine versus dAd5GNC + PBS (open triangles), F = 0.83, P > 0.3; dAd5GNC + cocaine versus naive + PBS, F = 0.1, P > 0.7; dAd5GNC + PBS versus naive + cocaine, F = 190, P < 0.0001; naive + cocaine versus naive + PBS (closed squares), F = 158, P < 0.0001. All statistics by repeated measures ANOVA within groups had no significant difference among the repetitions (F = 0.97, P > 0.4). (b) Total distance traveled in 10 minutes immediately following PBS or cocaine (50 µg) challenge plotted for each sequential weekly challenge (n = 15/group). In addition, the two experimental groups, naive or vaccinated animals, were challenged with PBS (negative control) between week 0 and 1 of cocaine challenges. dAd5GNC + cocaine (open circles) versus naive + cocaine (closed circles), F = 14.4, P < 0.006; dAd5GNC + cocaine versus naive + PBS (closed squares), F = 1.3, P > 0.2; dAd5GNC + PBS (open triangles) versus naive + cocaine, F = 37.4, P < 0.0001 (repeated measures ANOVA); dAd5GNC + cocaine versus dAd5GNC + PBS, F = 0.09, P > 0.7; naive + cocaine versus naive + PBS, F = 57.8, P < 0.0001 (nested ANOVA). All statistics by repeated measures ANOVA within groups for cocaine challenge had no significant difference (F = 0.08, P > 0.9). Note that the scales (ordinate) in a and b are different because different chambers were used, see Materials and Methods section. (a) 20 cm × 20 cm (Accusan Instruments). (b) 27 cm × 27 cm (Med Associates). Ad, adenovirus; GNC, (6-(2R,3S)-3-(benzoyloxy)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo [3.2.1] octane-2-carbonyloxy-hexanoic acid); PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

In successive weekly cocaine challenges, locomotor activity of the vaccinated mice was indistinguishable from naive or vaccinated mice that received PBS challenge and significantly less than naive mice receiving a cocaine challenge (Figure 4a,b). In each of the successive weekly cocaine challenges at 25 µg, locomotor activity in vaccinated mice was the same from that of naive or vaccinated mice that received PBS challenge, and significantly different than naive mice receiving a cocaine challenge (F = 40.9, P < 0.005). Activity measured at the higher dosage of 50 µg showed similar results, vaccinated mice challenged with cocaine remained significantly different than naive mice challenged with cocaine (F = 14.4, P < 0.006). Finally, the data indicated that this applies not just to the ambulatory activity but that the distribution of time spent in the four measured behaviors was significantly different (Figure 3c).

Discussion

The challenge of developing a vaccine directed toward addictive drugs is that the addictive drugs are small molecules and alone do not induce an immune response.1 A further challenge is the requirement for generation of high-titer, high-affinity antidrug antibodies sufficient to sequester in blood the high drug levels that follow rapid systemic drug administration.1,4,5,8 By covalently linking the small molecule addictive drug analog to the Ad, we are leveraging the robust humoral immune response against the Ad-capsid proteins9,10,13 to elicit high levels of high-affinity antibodies directed against the addictive drug covalently linked to the capsid proteins. Using cocaine as the model, we created the vaccine dAd5GNC by chemically crosslinking the cocaine analog, GNC, as a hapten to the proteins of a heat and detergent-disrupted E1−E3− Ad. Immunization with dAd5GNC evoked a high-titer humoral response to cocaine. By week 5 and beyond, the IgG1 subtype was dominant with an abundant IgG2a and IgG2b response. Vaccinated mice showed reduced brain levels of cocaine following an intravenous cocaine challenge with concomitant sequestering of cocaine by IgG antibodies in the blood. In humans, a reduction in the brain cocaine levels that result in less than half cocaine-bound dopamine transporter abrogate cocaine-induced perceived subjective “high”.14 Similar reductions in brain cocaine levels in mice may account for reduced hyperlocomotion behavior. Importantly, the behavioral effects induced in mice by intravenous administration of cocaine were decreased at doses that yield serum levels comparable to that observed in humans after cocaine administration.15,16 Regarding the comparison between species, the effects of a given level of cocaine as measured by locomotor behavior is likely to differ between species, although efficacy of a vaccine to neutralize a weight adjusted dose is relevant and is the common practice for vaccine development. Further, the dAd5GNC vaccine mediated immunological suppression of cocaine-induced hyperlocomotor activity in mice was persistent for multiple administrations over the course of weeks at higher than the weight adjusted human cocaine single dose. Despite the capacity to block these repeat challenges, the vaccine has not been evaluated in a short term, multiple administration model that may better represent an addict's behavior. If this degree of efficacy against weekly repeated administrations were to translate to humans,17,18 it may be effective in preventing or blunting relapse.17,18 The efficacy of the disrupted Ad for the cocaine application indicates that it may be a general platform for small molecule vaccines.

A variety of strategies have been investigated to evoke immunity against small molecule addictive drugs. For cocaine, vaccines that reduced cocaine-induced phenotypes have been generated by linkage of the cocaine analogs GNC or 6-((1R,2S,3S,5S)-3-benzamido-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2-carboxamido)hexanoic acid to KLH.4,18,19 Conjugation of the cocaine analog succinylated norcocaine to bovine serum albumin (BSA) or to cholera toxin B has also shown efficacy in rodent models,5,6 and the succinylated norcocaine-cholera toxin B-based vaccine has shown moderate reduction of cocaine use in human subjects.20,21 The cholera toxin B platform has also been used with a nicotine analog to generate an antinicotine vaccine, which has some success in experimental animals and is currently in clinical trials.22 Other antiaddictive drug vaccines that have been developed include a nicotine analog coupled to tetanus toxin,7 nicotine linked to Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoprotein A,4,8,23 and methamphetamine linked to an adjuvant peptide.24 Finally, nicotine linked to particles of the bacteriophage Qβ has generated some success in smoking abstinence in a subgroup of ex-smokers.25

The effectiveness of most of these antiaddiction active immunization strategies has been limited mostly because the antibodies elicited were not of sufficient titer and/or affinity to sequester in the blood the high, rapid bolus of systemic administration of the addictive drug. As an effective approach, several groups have developed antiaddictive drug antibodies that could be used as passive immunization to prevent the drug from reaching its brain receptors. For example, intravenous delivery of a humanized mouse monoclonal antibody directed against the cocaine analog GNC immediately prior to a cocaine challenge decreased cocaine-induced ambulatory behavior and at high dosage blocked the reinforcing effects of cocaine in rodents.18,19 A chimeric mouse-human anticocaine monoclonal was efficacious in preventing cocaine from reaching the brain in mice.26 Another passive immunity strategy has been to administer anticocaine catalytic antibodies that bind to and degrade cocaine.27,28 A combined active-passive strategy against addictive drugs uses a nicotine-specific IgG Ik mouse monoclonal antibody administered together with 3′-aminomethyl nicotine conjugated to recombinant Pseudomonas exoprotein A.8,23

General disadvantages to addictive drug immunotherapy include the challenge to activate an immune response that evokes antibody titer levels high enough to subvert an overwhelming dosage of the targeted drug, and the difficulty to maintain a persistent active immune response over the long term. These potential obstacles are key points for improvement during the research and development for an effective small molecule addictive drug immunotherapy. Confirmation of the vaccine's mechanism of suppression of cocaine-induced phenotype could be tested in future studies via the administration of a different stimulant such as amphetamine or caffeine to vaccinated animals.

In the present study, we have taken a novel approach to develop an antiaddictive drug vaccine by covalently coupling a cocaine analog to the capsid proteins of a disrupted Ad gene transfer vector. The concept behind the use of an Ad is the wealth of data demonstrating the high immunogenicity of the Ad-capsid proteins that elicit high-titer, high-affinity anticapsid protein immune responses in experimental animals, and importantly, in humans.9,10 The use of an E1−E3− Ad eliminates the possibility of toxic E1 gene products or E3 immunosuppressive products,11 and disruption of the Ad ensures that the Ad was not infectious, further enhancing the safety of the vaccine.

The concept of using a chemically disrupted virus or viral lysate as a vaccine is not new; disrupted/lysed virus vaccines have been developed for influenza, measles, polio, varicella-zoster, and Ad.29,30,31 The novel aspect of the platform in the present study is not the immunity evoked against the specific Ad per se, but the combination of the potent immunogenicity of the Ad to evoke immunity against a small nonimmunogenic molecule that has been coupled to the Ad-capsid proteins. To this strategy, we have added the concept of using an E1−E3− Ad that has been widely used in gene transfer applications, demonstrating an excellent safety profile that is well established32 and for which high-level, high-affinity anti-Ad capsid humoral antibodies in humans have been well documented.9,10 The dAd5GNC vaccine induced high-level anticocaine humoral response with a titer of 7.2 × 105 and affinity similar or higher compared to other vaccines including KLH-GNC and succinylated norcocaine to BSA.4,5 Further, dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice show reduced brain levels of cocaine following an intravenous cocaine challenge similar to other anticocaine vaccines and the anticocaine titers persist for 13 weeks, the longest period it was tested from the time of 1st administration of vaccine. Similarly studies of anticocaine vaccine efficacy have been evaluated using many behavioral phenotypes including locomotor activity, cocaine self administration, and stereotypy but the use of different routes of administration, and doses of cocaine challenge, animal species, evaluation times, and methods obfuscate comparisons. For the behavior phenotype used, the dAd5GNC is the first vaccine exhibiting nearly complete suppression of a cocaine-induced hyperactivity in mice.

Of interest, the anticocaine antibodies evoked by the dAd5GNC vaccine were dominated by a high IgG1and IgG2 isotype response. These isotype characteristics, combined with the rapid kinetics with which the antibodies evoked by dAd5GNC efficiently bind and sequester cocaine, are likely important in preventing the addictive drug from reaching its cognate receptors in the brain, despite the rapid bolus of systemic drug administration. As the protein G-Sepharose assay demonstrated that most of the cocaine in serum was IgG bound, it is likely to have a different degradation profile and clearance mechanism than free cocaine, future evaluation of any toxicology related outcome to other organs such as the heart and liver will be important for vaccine development. An effective anticocaine vaccine could most likely be useful in the prevention of recidivism in addicts attempting to stop their addiction.17,18 As a platform, disrupted Ad conjugate vaccines may prove to be useful for the development of vaccines for other addictive drugs.

Materials and Methods

dAd5GNC vaccine. A recombinant serotype 5 E1a−, partial E1b−, E3− Ad vector (“Ad5”) with β-galactosidase in the expression cassette in the E1− region was propagated and purified.33 Disruption of Ad5 vector was carried out (56 °C, 45 seconds) in 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The cocaine analog GNC (0.3 mg) was activated overnight at 4 °C after the addition of 7.2 µl charging solution, made by dissolving 2.4 mg of 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride and 2 mg of N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide in 4 µl H2O and 40 µl dimethylformamide. Conjugation of 200 µg of disrupted Ad vector (“dAd5”) with 6.7 µg charged GNC (30:1 GNC to Ad capsomere molar ratio) or 20 µg (100:1 GNC to Ad capsomere) was incubated overnight at 4 °C in 200 µl of PBS, pH 7.4 (PBS). The amount of Ad vector proteins was quantified by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Western analysis and β-galactosidase activity. To prepare an independent anti-GNC antibody, GNC was conjugated to KLH at a ratio of 2:1.4 Female BALB/c mice were immunized intramuscularly with 0.1 mg of KLH-GNC formulated in complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Polyclonal sera to be used as an anti-GNC reagent for western and ELISA analyses was collected from tail vein 10 weeks after immunization. For western analysis, dAd5GNC was resolved in 4–12% polyacrylamide sodium dodecyl sulfate gel under reducing conditions and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. To assess GNC conjugation, the membrane was stained with either the anti-GNC antibody or, to assess for the Ad components, anti-Ad antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The membranes were developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and ECL reagent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). To demonstrate the vaccine was not infectious, taking advantage of β-galactosidase as the transgene, A549 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were exposed to Ad5LacZ, dAd5LacZ, or dAd5GNC (n = 4, preparations). After 48 hours, the cells were treated with lysis buffer and assayed for activity using a high-sensitivity β-galactosidase assay kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Immunization with dAd5GNC. Female BALB/c mice, 4–6 week old (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME or Taconic, Germantown, NY) were housed under pathogen-free conditions and were used at 7–9 week of age. The mice were immunized by intramuscular injection to the quadriceps with 4 µg of dAd5GNC in 50 µl volume, formulated 1:1 in complete Freund's adjuvant for priming and incomplete Freund's adjuvant for boost at 3 and 6 week later. In order to complete the injection mice were restrained and quadriceps muscle located by palpating the anterior portion of the femur. The same general area was used for both the prime and boost vaccine administrations. Blood was collected from the transected tail vein, allowed to clot, centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 minutes, and the resulting serum was stored at −20 °C. All animal studies were conducted under protocols reviewed and approved by the Weill Cornell Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vitro assessment of anticocaine antibody levels and specificity for cocaine. Wells of flat bottomed 96-well enzyme immunoassay/radioimmunoassay plates (Corning, New York, NY) were coated with 100 µl of 1 µg/ml GNC-conjugated BSA in the ratio of 1:2 in carbonate buffer, pH 9.4 overnight at 4 °C (conjugation as described above but substitute BSA for dAd5). The plates were washed with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS (PBS-Tween) and blocked with 5% dry milk in PBS for 30 minutes at 23 °C. Twofold serial dilutions of serum were added to each well and incubated for 90 minutes at 23 °C. The plates were washed four times with PBS-Tween. For total IgG, 100 µl of 1:2,000 diluted horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 1% dry milk in PBS was added to each well, incubated for 90 minutes at 23 °C. Peroxidase substrate (100 µl/well; BioRad, Hercules, CA) was added and incubated for 15 minutes, 23 °C. For the rabbit anti-mouse isotype-specific antibody, 100 µl of anti-IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgM (BioRad) was added to each independent well and incubated in 1% dry milk in PBS for 90 minutes, 23 °C. The plates were washed four times, goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate was added for 90 minutes, incubated at 23 °C and the plates washed again. Peroxidase reaction was stopped with addition of 2% oxalic acid (100 µl/well). Absorbance was measured at 415 nm. Anti-GNC antibody titers were calculated by interpolation of the log(OD)−log(dilution) with a cutoff value equal to twofold the absorbance of background. To demonstrate that dAd5GNC evoked antibodies were cocaine-specific, inhibition of binding of dAd5GNC immune sera to BSA-GNC by ELISA were performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of GNC or cocaine, from 0.1 nmol/l to 0.1 mmol/l. Serum polyclonal antibody affinity was determined via a radioimmunoassay.12

Cocaine pharmacokinetics. Naive or dAd5GNC immunized mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) 2 minutes prior to tail vein administration of 2.5 µg cocaine containing 1.0 µCi [3H]cocaine (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). One minute later, the mice were killed and brain and trunk blood were collected separately. Brain tissue was homogenized in PBS and 300 µl of brain homogenate and 50 µl of serum were added to separate 5 ml liquid scintillant (Ultima Gold, PerkinElmer), assayed in triplicate for tritium and normalized with a standard quenching curve. For the blood compartment, cocaine was normalized to serum volume and brain was normalized to brain wet weight.

Cocaine-induced hyperactive behavior. Mouse locomotor behavior was recorded using infrared beam-equipped activity open-field chambers (27 cm × 27 cm chamber, Med Associates, St Albans, VT; 20 cm × 20 cm chamber, Accusan Instruments, Columbus, OH). All comparative controls were carried out in the same chambers. Data presented in Figures 3,4b were from experiments using the Med Associates chambers and when this equipment became unavailable, the data for Figure 4a was completed in the Accuscan chambers. Mice were allowed to habituate to the room for 1 hour prior to each test. Mice were placed in the chamber for 20 minutes to record baseline behavior, removed, injected with PBS or cocaine (25, or 50 µg) through the portal tail vein and returned to the chamber for 10–30 minutes. To establish upper limit of dosage, phenotypic behavior was tested at the dosage of 100 µg (intravenous), which resulted in aberrant behaviors, including seizures. Therefore, the dosage of 50 µg was selected as the highest dosage for measurement of cocaine induced phenotype in vaccinated mice. Experiments displayed in Figure 4b contain two experimental groups, naive or vaccinated animals. The two groups were repeatedly challenged with cocaine. These animals were also challenged with PBS (negative control) between 0 and 1 week of cocaine challenges. In addition to the two experimental groups, two “PBS only” control groups of animals (naive and vaccinated) were studied at weekly time points to establish the PBS baseline of animals never exposed to cocaine (Figure 4a). Locomotor activity was collected as ambulatory distance traveled or cumulative time associated with four standard behaviors; ambulatory or vertical movement, resting, and stereotypic behavior, measured as repeated breaking of the same photobeam.

Statistics. All data are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons between groups were conducted by one-way paired two sample t-test (Figure 2d). The t-test score is a measure of the significance of the difference between the means of the populations divided by the SE of their differences. Comparisons between experimental groups on the raw noncumulative ambulatory activity on a per minute basis were performed by three-way repeated measures ANOVA with immunization and cocaine challenge as the between subjects factor and time as the within subjects variable (Figure 3b). For post-hoc analysis the Scheffé test was performed at each time point. In addition, comparisons between experimental groups for cumulative ambulatory time were performed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (Figure 3b). The D score is a measure of the maximum difference between the distribution curves of the two samples tested. Pairwise comparisons between experimental groups for types of locomotor activity were by χ2 test of times for like behavioral activities (stereotypy, ambulatory, rest, vertical; Figure 3c). The χ² score is a relative measure of the difference of two sets of data weighed by the relative occupancy of the data point, more specifically, χ² is the sum of the squares of observed values minus expected values divided by the expected values. Comparisons were conducted by three-way repeated measures ANOVA with immunization and cocaine challenge as the between subjects factor and time as the within subjects variable (Figure 4a). Comparisons for the cocaine challenges were conducted by repeated measures ANOVA with immunization as the between subjects factor and time as the within subjects variable (Figure 4b). Comparisons of the cocaine challenges to the PBS controls involved different treatments applied to the same animals, so tests were conducted by nested ANOVA with distinct cocaine or PBS time points nested within the treatment factor. The F value measures the variance of the group means divided by the mean of the within-group variances. All statistical analyses were performed on Statview (ver 5; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or using R (ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice following cocaine or PBS challenge. Vaccinated or naive mice (n = 15 per group) were challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 μg) or PBS and locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus. Distribution of locomotor activities are mean values of percent time spent exhibiting indicated behavior ± SEM. Percent of time spent in ambulatory (black bars), vertical (grey bars), stereotypic (white bars) activity and at rest (diagonal lines) of naive or dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with PBS or 50 μg cocaine (4 wk after the 3rd immunization). dAd5GNC + PBS (control) vs naive + PBS (control) χ2 = 0.53, p>0.9; naive + cocaine vs both controls, dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 28.0, p<0.0001 and naive + PBS, p<0.0001; naive + cocaine vs dAd5GNC + cocaine, (χ2 = 32.5, p<0.0001); dAd5GNC + cocaine vs both controls, naive + PBS, χ2 = 0.99, p>0.8, and dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 1.6, p>0.6; Chi-square test. All studies carried out in the 27 cm × 27 cm Med Associates chamber (St. Albans, VT). Figure S2. Visual tracings of locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated and naive mice following cocaine challenge. Shown in this figure are the 2 groups of mice, naive and dAd5GNC vaccinated challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 μg) and naive injected with PBS as a negative control. Locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus (Med Associates). Each panel represents the horizontal activity (X and Y positions) of individual mice during the 10 min testing period. Images are screen captures of the 10 min activity tracings. Heavier lines show repeated crossings of the same area, with some mice preferring the outer walls. Each group was treated as follows: A. naive mice challenged with PBS at wk 1. B. naive mice challenged with 25 μg cocaine at wk 10. C. dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 25 μg cocaine at wk 10. D. Naive mice challenged with 50 μg cocaine at wk 12. E. dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 50 μg cocaine at wk 12. There are differences between the degree of travel of individual mice within each vaccinated or challenged condition, demonstrating the variability of the behavioral response to either PBS or cocaine. For example, some mice remain in the corners, while others travel the perimeter or cross the center of chamber (a subset of these panels representing each group are provided in Figure 3A).

Acknowledgments

We thank N Mohamed and T Benios for help in preparing this manuscript. These studies were supported, in part, by R01 DA025305 and RC2 DA028847. M.J.H. is supported, in part, by T32 HL094284; K.D.J., in part, by R01 DA008590; and M.T., in part, by R01 MH058669. The authors thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) drug supply program for the cocaine used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice following cocaine or PBS challenge. Vaccinated or naive mice (n = 15 per group) were challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 μg) or PBS and locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus. Distribution of locomotor activities are mean values of percent time spent exhibiting indicated behavior ± SEM. Percent of time spent in ambulatory (black bars), vertical (grey bars), stereotypic (white bars) activity and at rest (diagonal lines) of naive or dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with PBS or 50 μg cocaine (4 wk after the 3rd immunization). dAd5GNC + PBS (control) vs naive + PBS (control) χ2 = 0.53, p>0.9; naive + cocaine vs both controls, dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 28.0, p<0.0001 and naive + PBS, p<0.0001; naive + cocaine vs dAd5GNC + cocaine, (χ2 = 32.5, p<0.0001); dAd5GNC + cocaine vs both controls, naive + PBS, χ2 = 0.99, p>0.8, and dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 1.6, p>0.6; Chi-square test. All studies carried out in the 27 cm × 27 cm Med Associates chamber (St. Albans, VT).

Visual tracings of locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated and naive mice following cocaine challenge. Shown in this figure are the 2 groups of mice, naive and dAd5GNC vaccinated challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 μg) and naive injected with PBS as a negative control. Locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus (Med Associates). Each panel represents the horizontal activity (X and Y positions) of individual mice during the 10 min testing period. Images are screen captures of the 10 min activity tracings. Heavier lines show repeated crossings of the same area, with some mice preferring the outer walls. Each group was treated as follows: A. naive mice challenged with PBS at wk 1. B. naive mice challenged with 25 μg cocaine at wk 10. C. dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 25 μg cocaine at wk 10. D. Naive mice challenged with 50 μg cocaine at wk 12. E. dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 50 μg cocaine at wk 12. There are differences between the degree of travel of individual mice within each vaccinated or challenged condition, demonstrating the variability of the behavioral response to either PBS or cocaine. For example, some mice remain in the corners, while others travel the perimeter or cross the center of chamber (a subset of these panels representing each group are provided in Figure 3A).

REFERENCES

- Kinsey BM, Jackson DC., and, Orson FM. Anti-drug vaccines to treat substance abuse. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:309–314. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Angermeyer M, et al. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S., and, Peselow E. Pharmacotherapy of addictive disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32:277–289. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e3181a91655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera MR, Ashley JA, Parsons LH, Wirsching P, Koob GF., and, Janda KD. Suppression of psychoactive effects of cocaine by active immunization. Nature. 1995;378:727–730. doi: 10.1038/378727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox BS, Kantak KM, Edwards MA, Black KM, Bollinger BK, Botka AJ, et al. Efficacy of a therapeutic cocaine vaccine in rodent models. Nat Med. 1996;2:1129–1132. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantak KM, Collins SL, Lipman EG, Bond J, Giovanoni K., and, Fox BS. Evaluation of anti-cocaine antibodies and a cocaine vaccine in a rat self-administration model. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;148:251–262. doi: 10.1007/s002130050049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno AY, Azar MR, Warren NA, Dickerson TJ, Koob GF., and, Janda KD. A critical evaluation of a nicotine vaccine within a self-administration behavioral model. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:431–441. doi: 10.1021/mp900213u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyler DE, Roiko SA, Earley CA, Murtaugh MP., and, Pentel PR. Enhanced immunogenicity of a bivalent nicotine vaccine. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1589–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirmule N, Propert K, Magosin S, Qian Y, Qian R., and, Wilson J. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1574–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey BG, Hackett NR, El-Sawy T, Rosengart TK, Hirschowitz EA, Lieberman MD, et al. Variability of human systemic humoral immune responses to adenovirus gene transfer vectors administered to different organs. J Virol. 1999;73:6729–6742. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6729-6742.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wold WS, Doronin K, Toth K, Kuppuswamy M, Lichtenstein DL., and, Tollefson AE. Immune responses to adenoviruses: viral evasion mechanisms and their implications for the clinic. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:380–386. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(99)80064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R. Determination of affinity and specificity of anti-hapten antibodies by competitive radioimmunoassay. Meth Enzymol. 1983;92:589–601. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)92046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH., and, Nabel GJ. Adenovirus vector-based vaccines for human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:149–156. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, et al. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386:827–830. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benuck M, Lajtha A., and, Reith ME. Pharmacokinetics of systemically administered cocaine and locomotor stimulation in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Cone EJ., and, Henningfield JE. Arterial and venous cocaine plasma concentrations in humans: relationship to route of administration, cardiovascular effects and subjective effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1345–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF., and, Le Moal M. Drug abuse: hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science. 1997;278:52–58. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera MR, Ashley JA, Zhou B, Wirsching P, Koob GF., and, Janda KD. Cocaine vaccines: antibody protection against relapse in a rat model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6202–6206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera MR, Ashley JA, Wirsching P, Koob GF., and, Janda KD. A second-generation vaccine protects against the psychoactive effects of cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1988–1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041610998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell BA, Orson FM, Poling J, Mitchell E, Rossen RD, Gardner T, et al. Cocaine vaccine for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintained patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1116–1123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Gunderson EW, Jiang H, Collins ED., and, Foltin RW. Cocaine-specific antibodies blunt the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny T. Anti-nicotine vaccination: where are we. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2005;166:167–175. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26980-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiko SA, Harris AC, Keyler DE, Lesage MG, Zhang Y., and, Pentel PR. Combined active and passive immunization enhances the efficacy of immunotherapy against nicotine in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:985–993. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duryee MJ, Bevins RA, Reichel CM, Murray JE, Dong Y, Thiele GM, et al. Immune responses to methamphetamine by active immunization with peptide-based, molecular adjuvant-containing vaccines. Vaccine. 2009;27:2981–2988. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornuz J, Zwahlen S, Jungi WF, Osterwalder J, Klingler K, van Melle G, et al. A vaccine against nicotine for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AB, Tabet MR, Norman MK, Buesing WR, Pesce AJ., and, Ball WJ. A chimeric human/murine anticocaine monoclonal antibody inhibits the distribution of cocaine to the brain in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:145–153. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mets B, Winger G, Cabrera C, Seo S, Jamdar S, Yang G, et al. A catalytic antibody against cocaine prevents cocaine's reinforcing and toxic effects in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10176–10181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie KM, Mee JM, Rogers CJ, Hixon MS, Kaufmann GF., and, Janda KD. Identification and characterization of single chain anti-cocaine catalytic antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard S, Carlstroem G, Lagercrantz R., and, Norrby E. Immunization with inactivated measles virus vaccine. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1965;16:315–323. doi: 10.1007/BF01253829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salk J., and, Salk D. Control of influenza and poliomyelitis with killed virus vaccines. Science. 1977;195:834–847. doi: 10.1126/science.320661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinier-Frenkel V, Lengagne R, Gaden F, Hong SS, Choppin J, Gahery-Ségard H, et al. Adenovirus hexon protein is a potent adjuvant for activation of a cellular immune response. J Virol. 2002;76:127–135. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.127-135.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey BG, Maroni J, O'Donoghue KA, Chu KW, Muscat JC, Pippo AL, et al. Safety of local delivery of low- and intermediate-dose adenovirus gene transfer vectors to individuals with a spectrum of morbid conditions. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:15–63. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MA, Yoshimura K, Trapnell BC, Yoneyama K, Rosenthal ER, Dalemans W, et al. In vivo transfer of the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene to the airway epithelium. Cell. 1992;68:143–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90213-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated mice following cocaine or PBS challenge. Vaccinated or naive mice (n = 15 per group) were challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 μg) or PBS and locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus. Distribution of locomotor activities are mean values of percent time spent exhibiting indicated behavior ± SEM. Percent of time spent in ambulatory (black bars), vertical (grey bars), stereotypic (white bars) activity and at rest (diagonal lines) of naive or dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with PBS or 50 μg cocaine (4 wk after the 3rd immunization). dAd5GNC + PBS (control) vs naive + PBS (control) χ2 = 0.53, p>0.9; naive + cocaine vs both controls, dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 28.0, p<0.0001 and naive + PBS, p<0.0001; naive + cocaine vs dAd5GNC + cocaine, (χ2 = 32.5, p<0.0001); dAd5GNC + cocaine vs both controls, naive + PBS, χ2 = 0.99, p>0.8, and dAd5GNC + PBS, χ2 = 1.6, p>0.6; Chi-square test. All studies carried out in the 27 cm × 27 cm Med Associates chamber (St. Albans, VT).

Visual tracings of locomotor activity of dAd5GNC-vaccinated and naive mice following cocaine challenge. Shown in this figure are the 2 groups of mice, naive and dAd5GNC vaccinated challenged intravenously with cocaine (25 or 50 μg) and naive injected with PBS as a negative control. Locomotor activity was assessed in an open field apparatus (Med Associates). Each panel represents the horizontal activity (X and Y positions) of individual mice during the 10 min testing period. Images are screen captures of the 10 min activity tracings. Heavier lines show repeated crossings of the same area, with some mice preferring the outer walls. Each group was treated as follows: A. naive mice challenged with PBS at wk 1. B. naive mice challenged with 25 μg cocaine at wk 10. C. dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 25 μg cocaine at wk 10. D. Naive mice challenged with 50 μg cocaine at wk 12. E. dAd5GNC vaccinated mice challenged with 50 μg cocaine at wk 12. There are differences between the degree of travel of individual mice within each vaccinated or challenged condition, demonstrating the variability of the behavioral response to either PBS or cocaine. For example, some mice remain in the corners, while others travel the perimeter or cross the center of chamber (a subset of these panels representing each group are provided in Figure 3A).