Abstract

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are vulnerable to cervical spine fractures. Long-standing pain may mask the symptoms of the fracture. Radiological imaging of the cervical spine may fail to identify the fracture due to the distorted anatomy, ossified ligaments and artefacts leading to delay in diagnosis and increased risk of neurological complications. The objectives are to identify the incidence and risk factors for delay in presentation of cervical spine fractures in patients with AS. Retrospective case series study of all patients with AS and cervical spine fracture admitted over a 12-year period at Queen Elizabeth National Spinal Injuries Unit, Scotland. Results show that total of 32 patients reviewed with AS and cervical spine fractures. In 19 patients (59.4%), a fracture was not identified on plain radiographs. Only five patients (15.6%) presented immediately after the injury. Of the 15 patients (46.9%) who were initially neurologically intact, three patients had neurological deterioration before admission. Cervical spine fractures in patients with long-standing AS are common and usually under evaluated. Early diagnosis with appropriate radiological investigations may prevent the possible long-term neurological cord damage.

Keywords: Cervical fractures, Ankylosing spondylitis

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is seronegative autoimmune inflammatory arthritis that mainly affects the spine and the sacroiliac joints. The condition is associated with progressive ossification of the spinal ligaments and ankylosis of the facet joints eventually leading to a totally stiff spine [1]. Calcification of the longitudinal ligaments will eventually result in classical ‘bamboo spine’ appearance on the radiographs [1]. The fused spinal column looses its elasticity and movements resulting altered biomechanics. Progressive spinal deformity associated with stiffness, restricted spinal movements and osteoporosis increases the risk of fractures of the spine in these patients with devastating neurological complications. The estimated lifetime risk of fractures in ankylosed spine is 14% [2].

Risk factors for spinal fractures in ankylosing spondylitis have been evaluated in various studies. These factors include sex (male population being more susceptible), age, low body mass index, disease duration, osteoporosis, peripheral joint involvement, increased kyphosis [3], and alcohol use at the time of injury [4].

Chronic pain in patients with ankylosing spondylitis may mask the acute pain of the fractures [5]. These injuries also present a diagnostic dilemma at presentation because of lack of diagnostic clinical signs and symptoms of fractures after a trivial trauma and difficulty in obtaining decent images of the spine due to fixed flexion deformity of the neck [6].

This study was conducted to investigate the extent and sequelae of delays in diagnosis of cervical spine fractures in patients with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis.

Materials and methods

A retrospective case series study conducted at the Queen Elizabeth National Spinal Injuries Unit of Scotland. The unit is situated in a University Teaching Hospital, with specialist neurosurgical and orthopaedic support. The unit serves a population of 5.1 million and admits around one hundred and eighty patients annually. Patients with cervical spine fractures and ankylosing spondylitis between 1999 and 2007 were identified from the unit electronic database. Data were then collected form their clinical case records. Motor level and completeness of injury were based on American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) guidelines [7]. Radiographs, computed topographic (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were reviewed and relevant findings such as site and type of fracture noted. Initial radiographs were also reviewed in cases where the fracture was missed earlier. Demographic data, cause of injury, delay in diagnosis, neurological status on admission and discharge, functional outcome and complications were noted from the clinical case records for all patients.

Results

During 1995 to 2007, 32 (3 females and 29 males) patients were admitted to Queen Elizabeth National Spinal Injuries unit with ankylosing spondylitis and cervical spine fractures. One of these patients had both cervical and thoracic spine fracture during the same admission. Age ranged from 36 to 81 years (Mean 54.3 and Median 63 years). 11 Patients (34.3%) were above the age of 65 and 21 patients (59.3%) were between the ages of 45 and 65 years. Only a very small population was below the age of 45 (6.4%). The duration of the ankylosing spondylitis was variable ranging from 6 to 45 years and a mean duration of 23.7 years. 11 (34.3%) patients had ankylosing spondylitis for more than 30 years before their injury.

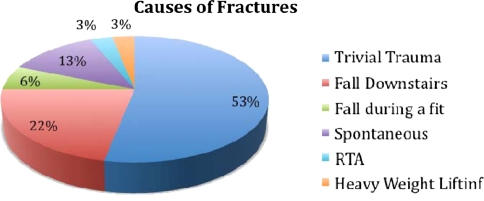

The most common cause of fracture of the cervical spine in our study was falls. This was observed in 26 cases: 17 sustained the injury after a trivial fall, 7 fell on stairs and 2 fell during a fit. Other causes of fractures included 4 (12.5%) spontaneous. 1 (3.1%) patient had high-speed road traffic accident and 1 (3.1%) patient sustained the fracture after lifting heavy weight (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Causes of cervical spine fractures in ankylosing spondylitis

Only 5 (15.6%) patients presented immediately after their injury, 12 (37.5%) patients presented within 12–24 h after the initial injury, 3 (9.4%) between 24 and 48 h, 4 (12.5%) between 48 and 72 h whereas 8 (25%) patients presented after more than 72 h (Table 1). One patient gave a history of minor trauma and increased intensity of pain of more than 6 months duration. It was however not clear from the radiographs whether his cervical spine fracture was spontaneous or secondary to this previous trauma.

Table 1.

Delay in initial presentation

| Time from injury to initial presentation | Number of patients (n = 32) |

Alcohol as contributory factor in injury (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| Immediately after injury | 5 (15.6%) | 3 |

| Between 12 and 24 h | 12 (37.5%) | 9 |

| Between 24 and 48 h | 3 (9.4%) | 2 |

| Between 48 and 72 h | 4 (12.5%) | 1 |

| More than 72 h | 8 (25%) | 3 |

18 (56.2%) patients were intoxicated with alcohol when injured. Of these only three patients presented immediately, nine patients within 24 h, two patients between 24 and 48 h, one patient between 48 and 72 h and three after 72 h (Table 1).

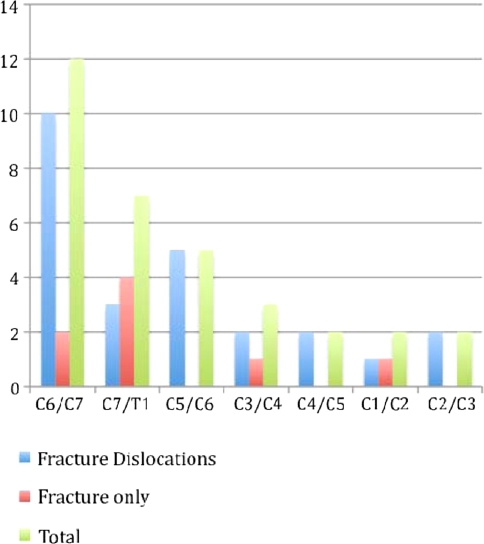

C6/C7 fracture dislocation was the most common pattern of cervical spine injury in ankylosing spondylitis occurring in 10 (31.2%) patients. Majority (75%) of injuries were at or below level of C5 and one patient sustained injury at both upper and lower cervical spine.

22 (62.7%) patients had unstable fractures with the fracture line going either through the body or through the ossified ligaments with displacement of the fragments. The pattern of cervical spine injuries in long-standing ankylosing spondylitis is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Pattern of cervical spine injuries in ankylosing spondylitis

In 19 patients (59.4%), no obvious pathology (either a fracture or dislocation) was seen on initial plain radiographs of the cervical spine. The fracture/dislocation was only visible on CT reconstruction or MRI scans.

15 (46.9%) patients were neurologically intact at the time of injury with American Spinal Injuries Association (ASIA) grade E and 7 (21.9%) patients had complete cord (ASIA grade A) injury. 10 patients sustained incomplete cord injury with 3 (9.3%) patients ASIA grade C and 7 (21.9%) ASIA grade D. However of the 15 patients with initially intact neurology, two presented late after deterioration in their neurology and at admission were ASIA grade D and one patient developed complete cord injury (ASIA grade A) after 5 days form injury (Table 2).

Table 2.

Neurological status at time of injury, admission and discharge

| ASIA grade | At the time of injury | At the time of admission | At the time of discharge |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 7 (21.9%) | 8 (25%) | 8 (25%) |

| B | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 3 (9.3%) | 3 (9.3%) | 1 (3.1%) |

| D | 7 (21.9%) | 9 (28.2%) | 5 (15.6%) |

| E | 15 (46.9%) | 12 (37.5%) | 18 (56.3%) |

Final outcome in terms of neurological recovery, walking status and development of complications during inpatient stay are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Outcome of cervical spine fractures in ankylosing spondylitis

| ASIA A on admission (n = 8) | ASIA C on admission (n = 3) | ASIA D on admission (n = 9) | ASIA E on admission (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological recovery on discharge | None | Partial recovery in two patients | Complete recovery in six patients | Complete recovery in all 12 patients |

| Complications rate in patient | 100% | 33% | 22% | 16% |

| Walking status on discharge | Wheelchair users | One patient walking with two sticks and two patients wheelchair users | One patient wheelchair user, two patients walking with sticks and six patients walking independently | All 12 patients walking independently |

Discussion

Fractures of the cervical spine are very serious and potentially fatal complication of the ankylosing spondylitis [8]. The cervical spine is the most common site of spinal fracture in patients with AS [9, 10]. Our study showed that 75% of patients had involvement of C5 and below. This is consistent with the literature as a review carried out by Hunter and Dubo [11] in 1978, showed that almost 75% of cervical spine fractures in ankylosing spondylitis involves the lower cervical spine (fifth through the seventh cervical spine vertebrae) or the cervicothoracic junction.

The force required to fracture the spine in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis is much smaller than to fracture a normal spine. This is due to the typical pathological changes in and around the spine [8, 12, 13]. The pathology involves osteoporosis, ankylosis, inter-vertebral disc calcification and ossification of the para-verteberal connective tissue. Long-standing disease will result in stiff spine with a characteristic appearance of “Bamboo Spine” on plain radiographs [14]. Calcification of the annulus fibrosis reduces the elasticity of the inter-vertebral disc and this is the site of least resistance during trauma [8, 9] leading to fractures even after a minor insult to the cervical spine. In our study 25 out of 32 of patients with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis sustained cervical spine fracture after trauma.

The incidence of mortality and morbidity is higher after a cervical spine fracture in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. This is mainly attributed to increasing age at presentation and the co-morbidities associated with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis [15, 16]. Secondary complications of fractures like partial or complete cord damage, disc herniation, dislocations and extradural haematoma will make the prognosis worst if these injuries are not treated appropriately [17]. In our study, three patients who were neurologically intact at the time of injury deteriorated in terms of their neurology at the time of admission because of the delay in diagnosis. One patient developed complete tetraplegia (ASIA-A) and two patients developed incomplete (ASIA-D) tetraplegia at the time of admission (Table 2).

18 of our patients sustained their injury whilst under the influence of alcohol with variable delay in presentation from the time of initial injury (Table 1). Association of alcohol and spinal cord injury is well documented in literature [18, 19]. The use of alcohol is associated with severe traumatic cervical spine injuries due to lack of protection from the rib cage, chest wall soft tissue and para-spinal muscles compared with other portion of the spine [4].

In our study only 5 patients (15%) presented immediately after their injury; 27 patients (85%) had at least 12-hour delay in presentation from time of initial injury. 15 out of 27 sustained the injury under influence of alcohol.

It is already known that alcohol can mask the acute symptoms of fractures by decreasing the feeling of pain and preventing the individual from seeking appropriate medical advice soon after the injury; thus delaying the diagnosis and increasing the risk of neurological complications [16]. The remaining 12 delays present in the hospital could be attributed to the lack of knowledge of the disease course by the patients or the presence of chronic cervical pain, which mask the acute symptoms.

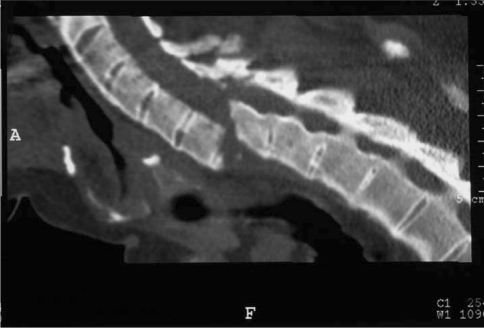

Plain radiographs of the cervical spine alone could be not sufficient to show the fractures configuration due to distorted anatomy, ossified ligament and osteopenia, or they could be difficult to interpret for a non-expert doctor in Accident and Emergency Department (Figs. 3, 4). Moreover there may be projection of the shoulder girdle over the lower cervical spine area, which may cause difficulty in interpreting radiographs. In 19 out of 32 patients (59.4%) the fractures were not spotted on the initial plain radiographs; in most cases (17 out of 19) patients proceeded to have CT or MRI scans based on clinical suspicion. However, two patients were discharged home based on their normal X-rays; subsequently both of them were diagnosed later, one complained of persistence of pain and the other one developed tetraplegia 5 days after initial trauma. CT scans can provide three-dimensional view of the distorted spine and can pick up subtle fractures that are not visible on plain radiographs (Fig. 5). It also shows the configuration of the fracture and the fragments. MRI is superior to CT scans as it provides information about the cord damage, intramedullary oedema and epidural haematoma.

Fig. 3.

Plain radiograph the cervical spine with no obvious fracture

Fig. 4.

Swimmers view of the same patient with a suspicious lesion

Fig. 5.

CT with sagittal reconstruction in the same patient showing an obvious three-column fracture

The delay in presentation and the inadequacy of the simple radiographs pose a particular clinical problem especially in the absence of major trauma and evolving neurological signs. It is imperative to have a high index of suspicion [6, 20] in ankylosing spondylitis patients who present with a history of minor trauma or without any neurological symptoms or signs, and to treat these patients as if they had a fracture until this has been excluded either by CT with sagittal reconstruction or by MRI scans [15]. It could be valuable as well to remember subtle clinical signs of fractures such as the improvement in the line of vision in these patients as a result of the change in the position of the otherwise fixed in flexion head [20].

11 (34.3%) of our patients were over the age of 65 years. This can be attributed to additional degenerative changes within the ankylosed spine. Cervical spine injuries in elderly population, in the presence of ankylosing spondylitis, are associated with increased mortality [15] due to poor nutritional and respiratory status, chronic medication with steroid or anti-inflammatory and stiffness of the chest leading to difficulty in clearing the airways. Reducing the incidence of delayed diagnosis of cervical spine fractures in these patients may improve the prognosis [6].

Conclusion

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis are susceptible to spinal fractures with trivial trauma and even to occult fractures. Late presentation of patients to hospital is a possibility; alcohol is a risk factor for these. Patient’s education may play an important role in the early diagnosis and the prevention of long-term neurological complications.

Plain radiographs may not identify these fractures. Prevention of missing a fracture is a priority. Hence, any changes in character of long-standing cervical pain especially after a minor trauma and in old age group should be treated as unstable spinal fracture until proved otherwise. Investigation must include CT or MRI scans if the plain radiographs do not show any evidence of fracture.

References

- 1.Mansour M, Cheema GS, Naguwa SM, Greenspan A, Borchers AT, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Ankylosing spondylitis: a contemporary perspective on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:210–233. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mundwiler M, Siddique K, Dym J, et al. Complications of the spine in ankylosing spondylitis with a focus on deformity correction. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:1–9. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/1/E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geusens P, Vosse D, Liden S. Osteoprosis and vertebral fractures in ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:335–339. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328133f5b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrison A, Clifford K, Gleason SF, Tun CG, Brown R, Garshick E. Alcohol use associated with cervical spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27:111–115. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2004.11753740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gran JT, Skomsvoll JF. The outcome of ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:766–771. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.7.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein JA, Chapman JR, Mirza S. Occult vertebral fractures in ankylosing spondylitis. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:444–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ditunno JF, Young W, Donovan WH, Creasey G. The international standards booklet for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Americal Spinal Injury Association. Paraplegia. 1994;32:70–80. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray GC, Persellin RH. Cervical fracture complicating ankylosing spondylitis. A report of eight cases and review of literature. Am J Med. 1981;70:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detwiller KN, Loftus CM, Godersky JC, Menzes AH. Management of spine injuries in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Neurosurg. 1989;72:210–215. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.2.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alaranta H, Luoto S, Konittinen YT. Traumatic spinal cord injury as a complication to ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter T, Dubo H. Spinal fractures complicating ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:546–549. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-4-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foo D, Sarkarati M, Marcelino V. Cervical spinal cord injury complicating ankylosing spondylitis. Paraplegia. 1985;23:358–363. doi: 10.1038/sc.1985.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iplikcioglu AC, Bayar MA, Kokes F, Gokcek C, Doganay OS. Magnetic resonance imaging in cervical trauma associated with ankylosing spondylitis: report of two cases. J Trauma. 1994;36:412–413. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199403000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smartizis D, Anderson DG, Shen FH. Multiple and simultaneous spine fractures in ankylosing spondylitis. Spine. 2005;30:711–715. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000188272.19229.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olerud C, Andersson S, Svensson B, Bring J. Cervical spine fractures in the elderly: factors influencing survival in 65 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:509–513. doi: 10.3109/17453679909000990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myllykangas-Lousujarvu R, Aho K, Lehtinen K, Kautiainen H, Hakala M. Increased incidence of alcohol related deaths from accidents and violence in subjects with ankylosing spondylitis. Eur Spine J. 1996;5:51–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00307827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anwar F, Al-Khayer A, Fraser M, Allan DB. Concomitant cervical and thoracic spinal fractures in ankylosing spondylitis: a case report and review of literature. Injury Extra. 2009;40:242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.06.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke DA, Linden RD, Zhang YP, Meiste AC, Shields CB. Incidence rates and populations at risk for spinal cord injury: a regional study. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:274–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26:S2–S12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112151-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham B, Pereghem K. Fractures of the spine in ankylosing spondylitis. Spine. 1989;14:801–807. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]