Abstract

Background

Numerous reports of THAs in patients younger than 30 years indicate a high risk of revision. Although risk factors for revision have been reported for older patients, it is unclear whether these risk factors are the same as those for patients younger than 30 years.

Questions/purposes

We therefore (1) determined function and survivorship of revision THAs performed in patients younger than 30 years, and (2) assessed the risk factors for revision THAs in this younger population by comparison with a group of patients younger than 30 years who did not undergo revision.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records and radiographs of 55 patients younger than 30 years (average age at revision, 24.3 years; range, 14–30 years) who underwent 77 hip revisions. Revision was performed, on average, 4.6 years (range, 0.4–12 years) after the primary THA. The results for these 55 patients (77 revision THAs) were compared with results for a nonrevised group, including 819 THAs in patients younger than 30 years. Minimum followup of the revision group was 1 year (mean, 6.2 years; range, 1–15 years).

Results

At followup after the revision, the Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score improved from 12.2 to 14.6. The rates of dislocation, neurologic lesions, and fractures were 15%, 7.8%, and 14%, respectively. The 10-year survival rate was 36% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21%–51%). Compared with the nonrevised group, the independent revision risk factors were young age at primary THA (OR 1.14 [1.07–1.19]), high number of previous surgeries (OR 5.41 [2.67–10.98]), and occurrence of at least one dislocation (OR 3.98 [1.74–9.07]). Hard-on-soft bearings had a higher risk (OR 3.42 [1.91–6.1]) of revision compared with hard-on-hard bearings.

Conclusions

Revision THAs are likely in patients younger than 30 years, and the complication rate is high. The survivorship of hip revision in this population is low and alternative solutions should be advocated whenever possible.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study, case control study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

THA in young and active patients is a challenge [25, 30]. The need for revision arthroplasty has increased owing to the higher life expectancy of these patients [12]. Younger patients frequently need surgery because of preexisting conditions and previous surgery. Femoral or acetabular osseous lesions and muscle damage lead to difficult reconstruction impairing the function of THA in these young patients [20]. THA revision in this population requires comprehensive knowledge of failure (bearing components, implant fixation, etiologies, etc) to prevent repeated surgeries, reduce wear, and improve the survivorship [6, 25, 29, 31].

Numerous studies report primary THAs in patients younger than 30 years [4, 6, 25, 30, 32, 35, 38] with global revision rates ranging from 4% to 33%, [12, 25, 30, 32, 35, 38]. These reported rates are much higher than those reported for older patients (range, 7%–15%) with a longer followup [3, 18, 19, 21]. However, none of these studies of patients younger than 30 years described the function or survival of revision THA. Likewise, none of the studies accurately assessed the reasons for failure of the THA, usually because the number of patients included in the studies was limited as THA in younger patients is not that common [4, 10, 25, 29].

Based on a large population of primary and revision THAs in patients younger than 30 years, we therefore (1) determined function and survivorship of revision THAs in this specific population, and (2) assessed the risk factors for revision THAs in this younger population by comparison with a group of patients younger than 30 years who did not undergo revision.

Patients and Methods

In 2008, a multicenter trial was conducted in 23 French centers specializing in THA for young patients. All THAs (total 941) performed between January 1985 and December 2003 in patients younger than 30 years with a minimum followup of 5 years were included. We excluded THAs performed for patients with active hip infection or tumors. Of the 941 primary THAs, 199 were revised (revision rate, 21%), and of these 199 revisions, 122 (92%) were in patients older than 30 years, and 77 (8%; 55 patients) were in patients younger than 30 years, which formed our study group (Table 1). In the study group, the primary THA was performed at a mean age of 19.7 years (range, 12–29 years) and revision at a mean age of 24.3 years (range, 14–30 years). The revision was performed, on average, 4.6 years (range, 0.4–12 years) after the primary THA. Reasons for revision included aseptic loosening in 40 cases (51%), wear in 19 (24%), recurrent dislocation in four (6%), implant breakage in three (4%), infection in six (8%), and osteolysis in five (7%). Revision involved the stem and cup in 21 cases and was limited to one component in 56 cases (stem in 14 cases, insert exchange in five cases, and cup revision in 37 cases) (Fig. 1). The acetabular side was revised in 88% (n = 68), and the femoral side in 40% (n = 31). The height, weight, and gender ratio were, respectively, 162 cm (range, 114–198 cm), 56.8 kg (range, 37–100 kg), and 28/27 (male/female). Minimum followup of the revised group was 1 year (mean, 6.2 years; range, 1–15 years). Two patients were lost to final followup.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, etiologic, and radiologic data for both patient groups

| Parameter | Nonrevised | Revision before age 30 years | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hips (number of patients) | 819 (625) | 77 (55) | |

| Age at primary THA (years) | 23.2 (16–29) | 19.7 (12–29) | p < 0.0001 |

| Mean number of previous surgeries | 0.67 (0–17) | 1.8 (0–15) | 0.003 |

| Body mass index | 26.8 (15.7–34.8) | 25.5 (14.4–36.9) | 0.8 |

| Gender ratio | M = 330/F = 295 | M = 28/F = 27 | 0.9 |

| Cup inclination (°) | 43.6° (15–62) | 44.3° (18–68) | 0.5 |

| Cup diameter (mm) | 50.2 | 48.8 | p = 0.003 |

| Merle d’Aubigné-Postel score at last followup | 15.9 (6–18) | 14.6 (8–18) | p = 0.02 |

| WOMAC score at last followup | 21 (5–60) | 20.1 (4–65) | p = 0.1 |

| Dislocation rate | 5% | 15% | p < 0.001 |

| Early dislocation (within 3 months) | 2.5% | 10% | p = 0.002 |

| Intraoperative fracture | 5.6% | 14% | p < 0.001 |

| Postoperative neurologic palsy | 2% | 7.8% | p < 0.001 |

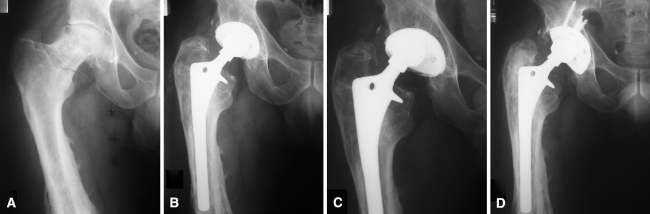

Fig. 1A–D.

(A) A preoperative radiograph shows osteoarthritis secondary to septic sequelae of a femoral shaft fracture in a 24-year-old woman. The indication for THA was retained. (B) A postoperative radiograph shows a bipolar cementless THA with a hard-on-soft bearing surface. (C) A radiograph taken at the 4-year followup shows, despite an asymptomatic hip, there is considerable polyethylene liner wear without acetabular osteolysis, which led to revision. (D) Acetabular revision was performed with a new cup (polyethylene insert) fixed with five screws without bone graft.

The 819 nonrevised THAs (625 patients; 330 males/295 females) in the initial group of 941 patients younger than 30 years constituted the control group (Table 1). The control and study groups were comparable regarding gender and body mass index (Table 1). However, patients in the study group were younger and had a greater number of previous surgeries to the hip (Table 1). Likewise, the etiologies for primary THAs between the revised and nonrevised groups were different (Table 2). There were more pediatric diseases (slipped capital femoral epiphysis, congenital hip dislocation, developmental hip dysplasia, osteochondritis, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease) (25% versus 18%; p = 0.008), more sequelae of infection during childhood (16% versus 8%; p = 0.003), and fewer inflammatory diseases (13% versus 21%; p = 0.004) in the revised group than in the nonrevised group.

Table 2.

Etiologies and bearing types implanted at the time of primary insertion

| Parameter | Nonrevised | Revision before age 30 years | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology | |||

| Pediatric diseases | 18% (147) | 25% (19) | p = 0.008 |

| Septic sequelae | 8% (65) | 16% (12) | p = 0.003 |

| Inflammatory diseases | 21% (172) | 13% (10) | p = 0.004 |

| Traumatic sequelae | 14% (115) | 17% (13) | 0.1 |

| Neurologic diseases | 7% (58) | 1% (1) | 0.1 |

| Avascular necrosis | 26% (213) | 20% (15) | 0.09 |

| Primary osteorthritis | 6% (49) | 8% (6) | 0.1 |

| Type of bearing implanted | Type of bearing revised | ||

| Hard-on-soft bearings | 66% (540) | 91% (70) | p < 0.001 |

| Metal head | 41% (336) | 56% (43) | |

| Ceramic head | 25% (204) | 35% (27) | |

| Hard-on-hard bearings | 34% (279) | 9% (7) | p < 0.001 |

| Ceramic-on-ceramic | 20% (165) | 6.5% (5) | p < 0.001 |

| Metal-on-metal | 14% (114) | 2.5% (2) | p < 0.001 |

Clinical function and functional status were assessed respectively according to the Merle d’Aubigné-Postel (PMA) hip rating system [23] and Charnley’s classification [5]. Activity level was rated according to the scale described by Devane et al. [9], and health status was measured by WOMAC score [1]. Before revision surgery, according to the classification of Devane et al., few patients (28%) were very active (Grade 4 or 5); the majority had a low activity level (14% Grade 1, 25% Grade 2, 33% Grade 3, 18% Grade 4, and 10% Grade 5).

AP and lateral radiographs were obtained annually and at last followup in 2008. They were assessed by two observers (JG, FB) who did not participate in the surgeries. The acetabular components were analyzed for migration, wear, and radiolucent lines. Cup migration was detected by measuring changes in position of the center of articulation with respect to the acetabular teardrops. Variations greater than 5 mm or 5° between followup radiographs were considered as indicating migration. Cementless components were examined according to the seven femoral zones of Gruen et al. [15] and the three acetabular zones of DeLee and Charnley [7] for osteolysis and radiolucent lines. Loosening was considered probable if radiolucent lines exceeding 1 mm for cemented cups or dense, reactive lines for cementless cups in the three zones of DeLee and Charnley [7] were observed. For cemented stems, loosening and migration were evaluated according to the criteria of Harris et al. [16]. For cementless stem fixation, the criteria of Engh et al. [13] were used.

The function and complications were respectively reported by means, range, and frequency. We determined the differences in functional parameters from preoperative to followup by ANOVA and chi square tests; nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon, Mann-Whitney, Fisher) were used when samples were small. Survival analysis (with 95% CIs) was conducted according to Kaplan-Meier, with reoperation for any reason and component exchange as end points. We determined factors influencing reoperation rate by comparing differences in those parameters using t and chi square tests and nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon, Mann-Whitney, Fisher) when samples were small. The odd ratios (with 95% CI) were calculated for factors that influenced risk for reoperation between the study and control groups. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was applied to test the independence of the factors that influenced the reoperation rate in univariable analysis. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS® software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The function after revision in the study group improved according to the PMA score that increased (p = 0.008) from 12.2 to 14.6 at latest followup (Table 1). Pain, mobility, and gait improved respectively from 3.6 to 4.5 (p = 0.001), 4.9 to 5.4 (p = 0.009), and 4.1 to 4.9 (p = 0.006). At latest followup, the global WOMAC score was 20.1 (range, 4–65). There was an increase (p = 0.02) in activity level: at followup 30 patients (56%) were rated Grade 4 or 5 versus 15 patients (28%) before revision. Before revision surgery 31% of patients had a leg-length discrepancy greater than 10 mm (average, 1.9 cm; range, 0.5–8 cm), that improved at latest followup, with 9% of patients having inequality greater than 10 mm (average, 0.8 mm; range, 1–5 mm). THA revision was repeated in 42 of the 77 index cases (rate of new revision, 55%). Revisions were needed owing to aseptic loosening (18 cases, 46%), polyethylene wear (10 cases, 28%), recurrent dislocation (six cases, 11%), periprosthetic fracture (five cases, 10%), infection (two cases, 3%), and stem breakage (one case, 2%). Consequently, with THA revision for any reason as the end point, the 10-year survival rate of the study group was only 36% (95% CI, 21%–51%). If the function was acceptable, the radiologic features were more disappointing among the 35 THAs without repeat revision: the cup was considered stable in 28 hips (80%), unstable in six (17%), and uncertain in one (3%). Likewise the stem was deemed stable in 32 hips (92%), unstable in one (3%), and uncertain in two (5%). Acetabular osteolysis was observed for cemented and cementless cups in 12% and 24%, respectively.

Various factors appeared to influence the revision rate of THAs performed in patients younger than 30 years (Tables 1 and 2). However, only four factors independently influenced the rate of revision: (1) the use of hard-on-soft bearings in 66% of the nonrevised THAs, as opposed to 91% of the revised cases (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The odds ratio related to the use of hard-on-soft bearings was 3.42 (1.91–6.1); (2) younger ages at the time of primary THA (19.7 versus 23.2 years; p < 0.0001). Younger age at primary THA was a risk factor regarding revision with an odds ratio of 1.14 (1.07–1.19); (3) more than two previous surgeries (p = 0.003) with an odds ratio of 5.41 (2.67–10.98); and (4) at least one dislocation after the primary THA (p = 0.04) with an odds ratio of 3.98 (1.74–9.07). In contrast small cup diameter did not influence the reoperation rate as an independent factor. Similarly, cemented or cementless fixation (p = 0.5) and activity level according to the score of Devane et al. [9] (p = 0.7) did not correlate with the risk for revision.

Complications were more frequent after revision THA than after primary THA in this specific population (Table 1). The dislocation rate tripled (p < 0.001) after revision compared with that of the nonrevised group (15% versus 5%, respectively). The dislocation rate within 3 months was greater (p = 0.002) in the revised group than in the nonrevised group (10% versus 2.5%, respectively). Intraoperative complications (acetabular or femoral fractures and postoperative palsy) were greater (p < 0.001) than those for revision THA in comparison to primary THA.

Discussion

Hip replacement in patients younger than 30 years is a demanding procedure when considering the life expectancy and activity level of these younger patients. Studies analyzing hip replacements in this population suggest a high risk of reoperation ranging from 14% to 43% (Table 3) [12, 25, 30, 32, 35, 38]. Although risk factors for revision are well known in older patients, it is unclear whether these risk factors are the same as those for patients younger than 30 years. Considering the high risk of reoperation and use of THA as a more common procedure in young patients, it appears necessary to investigate the reason for failure to identify patients at risk for revision, and if possible, to prevent these factors or to improve the selection of patients for alternative procedures.

Table 3.

Summary of different THA revision rates in patients younger than 30 years reported in the literature

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a multicenter study. The centers were selected according to an adequate level of expertise and it is possible that the findings might differ in low volume centers. Second, we included various prosthesis designs. However, surgeons at all participating centers had extensive experience with their specific implants. Third, although the study was retrospective we included a relatively large number of patients and procedures (941 primary THAs, 55 revision THAs) and a control group (819 nonrevised THAs).

Initially, function appears acceptable with a mean PMA score of 14.6 of 18 points; however, this was significantly worse than for primary THAs in the control subjects (Table 1). Survivorship of THA revisions done in patients younger than 30 years are less optimistic when considering the 55% repeat revision rate and the low survivorship of only 36% at 10 years. Because of these disappointing survivorship some authors advocated hip arthrodesis to prevent mechanical failure of the THA in this highly demanding population [33]. This option and conservative surgery should be considered whenever possible, particularly when considering the short followup of only 5 years for this study and the long life expectancy of these patients [36]. We identified mainly polyethylene wear (28%) and loosening (46%) as reasons for revision THAs, therefore, recommending alternative bearings when possible as an option. Small-diameter metal-on-metal prostheses [11, 24] had a lower revision rate in our patients, and should be considered for patients with a smaller skeleton.

Among the indications for primary THA, pediatric diseases and septic sequelae were suspected to have a greater risks for revision, but they were not confirmed as independent factors by multivariable analysis. Contrary to the studies of Chandler et al. [4] and Torchia et al. [35], we did not find higher risk for revision for THA performed for vascular necrosis and posttraumatic sequelae. Some factors cited in the literature as being correlated with an increased risk of revision were not identified in the current study, such as weight greater than 60 kg [38], high activity level [4, 38], unilateral osteoarthritis [35], and the use of corticosteroids [38]. However, we confirmed the adverse influence of repeat former surgeries before the primary THA [35], suggesting that conservative procedures should be considered more adequately in this young population. The main THA failure mechanism identified was aseptic loosening, which correlates with polyethylene wear [9, 17, 31]. In these young patients, hard-on-soft bearings were correlated with a lower survival rate. We recommend the use of hard bearings if possible, particularly when considering the higher wear rate of thinner polyethylene inserts usually used in this population when hard-on-soft bearings are used [2, 8, 9, 17, 25]. Instead of activity level, younger age at the time of primary THA was a risk factor for revision in the current study. This finding contrasts with that of other studies [9, 31], but these studies were performed in older populations. We found cementless or cemented primary THA prostheses designs had no correlation with revision probability. The literature seems to agree with these data showing comparable revision rates after THA implantation of cemented or cementless implants in the general population [24, 39]. In patients younger than 30 years, with 6 years’ followup, Restrepo et al. [29] reported only one revision with cementless implants, with excellent bone stock ongrowth. However, high rates of loosening of the cemented cup in primary and revision THAs in younger patients [4, 6, 10, 11, 34] seem to encourage the use of cementless cup components.

The clinical function is identical to this seen after THA revisions in the older population [2, 8]. In contrast, types of complications were different from those after revision in older patients. The fracture rate (14%) in our patients was lower than the rate after THA revision in older patients (16% reported by Park et al. [27], 22% reported by Farfalli et al. [14], and 30% reported by Meek et al. [22]). The dislocation rate (15%) for our patients was higher than usually observed after revision THAs (5% reported by Park et al. [27], 8% reported by Kinkel et al. [20], and 9% reported by Ornstein et al. [26]). In our series, all prosthetic heads had a diameter of 22 or 28 mm. Larger femoral heads (> 38 mm), currently introduced with metal-on-metal bearings (in large femoral head arthroplasty or hip resurfacing), should be considered to avoid impingement and to prevent dislocation in this active population [28, 37].

Revision THAs are likely in patients younger than 30 years, and the complication rate is high. This should be kept in mind when the primary procedure is indicated in such a population. The survivorship of hip revision in a young population is low, and alternative solutions are advocated whenever possible. Alternative hard bearings provided for a lower revision rate in this specific population, but there are concerns regarding their use and longer followup is mandatory to confirm this data. Revision THA in a population younger than 30 years is associated with a higher revision rate and lower survival rate than those with primary THA. The complication rate is high and correlates with muscular and/or osseous lesions owing to revision surgery. Postoperative dislocations are frequent and should be prevented (with large-diameter heads, respect of abductor muscles, etc). Hard-on-soft bearings appear to be an important risk factor for mechanical failure. Considering survivorship in the current study, hard-on-hard bearings (metal-on-metal or ceramic-on-ceramic) seem to be preferred for these young and active patients rather than hard-on-soft bearings. However, in patients with dysplastic hips, the often small sizes of the femoral head and the limited acetabular bone available for supporting an implant may be inconsistent with some hard-on-hard bearing designs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alain Duhamel for help with managing statistics. The authors warmly thank the French Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatology (SoFCOT) for allowing publication of the data.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Lille University Hospital.

References

- 1.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnomet F, Clavert P, Laffargue P, Duhamel A. Global results and complications. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2000;86(suppl 1):48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan JJ, Templeton JE, Liu SS, Pedersen DR, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Results of Charnley total hip arthroplasty at a minimum of thirty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:690–695. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old: a five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1426–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charnley J. Low Friction Arthroplasty of the Hip: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Springer; 1979:60.

- 6.Chmell MJ, Scott RD, Thomas WH, Sledge CB. Total hip arthroplasty with cement for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: results at a minimum of ten years in patients less than thirty years old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:44–52. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomasson E, Guingand O, Terracher R, Mazel C. [Perioperative complications after total hip revision surgery and their predictive factors: a series of 181 consecutive procedures] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2001;87:477–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devane PA, Horne JG, Martin K, Coldham G, Krause B. Three-dimensional polyethylene wear of a press-fit titanium prosthesis: factors influencing generation of polyethylene debris. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:256–266. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years: a nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;260:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorr LD, Wan Z, Longjohn DB, Dubois B, Murken R. Total hip arthroplasty with use of the Metasul metal-on-metal articulation: four to seven-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:789–798. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudkiewicz I, Salai M, Israeli A, Amit Y, Chechick A. Total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 30 years of age. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:709–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engh CA, Massin P, Suthers KE. Roentgenographic assessment of the biologic fixation of porous-surfaced femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;257:107–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farfalli GL, Buttaro MA, Piccaluga F. Femoral fractures in revision hip surgeries with impacted bone allograft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:130–136. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318137968c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris WH, McCarthy JC, Jr, O’Neill DA. Femoral component loosening using contemporary techniques of femoral cement fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:1063–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jialiang T, Zhongyou M, Fuxing P, Zongke Z, Bin S, Jing Y. Primary total hip arthroplasty with Duraloc cup in patients younger than 50 years: a 5- to 7-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1184–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keener JD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Pederson DR, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC. Twenty-five-year results after Charnley total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty years old: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1066–1072. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerboull L, Hamadouche M, Courpied JP, Kerboull M. Long-term results of Charnley-Kerboull hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 50 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:112–118. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinkel S, Kaefer W, Reissig W, Puhl W, Kessler S. Revision total hip arthroplasty: the influence of gender and age on the perioperative complication rate. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2003;70:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewthwaite SC, Squires B, Gie GA, Timperley AJ, Ling RS. The Exeter Universal hip in patients 50 years or younger at 10–17 years’ followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:324–331. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0049-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meek RM, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Greidanus NV, Duncan CP. Intraoperative fracture of the femur in revision total hip arthroplasty with a diaphyseal fitting stem. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:480–485. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merle D’Aubigne R. [Numerical evaluation of hip function] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1970;56:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Migaud H, Jobin A, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Laffargue P, Duquennoy A. Cementless metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in patients less than 50 years of age: comparison with a matched control group using ceramic-on-polyethylene after a minimum 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(83):23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odent T, Journeau P, Prieur AM, Touzet P, Pouliquen JC, Glorion C. Cementless hip arthroplasty in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:465–470. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000161096.53963.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ornstein E, Atroshi I, Franzen H, Johnsson R, Sandquist P, Sundberg M. Early complications after one hundred and forty-four consecutive hip revisions with impacted morselized allograft bone and cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1323–1328. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park YS, Moon YW, Lim SJ. Revision total hip arthroplasty using a fluted and tapered modular distal fixation stem with and without extended trochanteric osteotomy. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters CL, McPherson E, Jackson JD, Erickson JA. Reduction in early dislocation rate with large-diameter femoral heads in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(62):140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Restrepo C, Lettich T, Roberts N, Parvizi J, Hozack WJ. Uncemented total hip arthroplasty in patients less than twenty-years. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruddlesdin C, Ansell BM, Arden GP, Swann M. Total hip replacement in children with juvenile chronic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:218–222. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B2.3958006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmalzried TP, Shepherd EF, Dorey FJ, Jackson WO, dela Rosa M, Fa’vae F, McKellop HA, McClung CD, Martell J, Moreland JR, Anstutz HC. The John Charnley Award. Wear is function of use, not time. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;381:36–46. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sochart DH, Porter ML. Long-term results of cemented Charnley low-friction arthroplasty in patients aged less than 30 years. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:123–131. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stover MD, Beaule PE, Matta JM, Mast JW. Hip arthrodesis: a procedure for the new millennium? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:126–133. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stromberg CN, Herberts P, Ahnfelt L. Revision total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 55 years old: clinical and radiologic results after 4 years. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3:47–59. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(88)80052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torchia ME, Klassen RA, Bianco AJ. Total hip arthroplasty with cement in patients less than twenty years old: long-term results. J Bone J Surg Am. 1996;78:995–1003. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X78B6.7170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turgeon TR, Phillips W, Kantor SR, Santore RF. The role of acetabular and femoral osteotomies in reconstructive surgery of the hip: 2005 and beyond. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:188–199. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000193541.72443.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vendittoli PA, Lavigne M, Girard J, Roy AG. A randomised study comparing resection of acetabular bone at resurfacing and total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:997–1002. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witt JD, Swann M, Ansell BM. Total hip replacement for juvenile chronic arthritis. J Bone J Surg Br. 1991;73:770–773. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B5.1894663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young L, Duckett S, Dunn A. The use of the cemented Exeter Universal femoral stem in a District General Hospital: a minimum ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:170–175. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]