Abstract

Background

Open débridement with polyethylene liner exchange (ODPE) remains a relatively low morbidity option in acute infection of total knee arthroplasty (TKA), but concerns regarding control of infection exist. We sought to identify factors that would predict control of infection after ODPE.

Methods

We identified 44 patients (44 knees) with culture-positive periprosthetic infection who underwent ODPE. Failure was defined as any reoperation performed for control of infection or the need for lifetime antibiotic suppression. Patients had been followed prospectively for a minimum of 1 year (mean, 5 years; range, 1–9 years).

Results

Twenty-five of the 44 patients (57%) failed ODPE. Of these 25 patients, two had one additional procedure, 21 had more than one additional procedure, and two required lifetime antibiotic suppression. Failure rates tended to differ based on primary organism: 71% of Staphylococcus aureus periprosthetic infection failed versus 29% of Staphylococcus epidermidis, although with the limited numbers theses differences were not significant. Age, gender, or measures of comorbidity did not influence the risk of failure. There was no difference in failure rate (58% versus 50%) when the ODPE was performed greater than 4 weeks after index TKA. After a failed ODPE, 19 of the 25 failures went on to an attempted two-stage revision procedure. In only 11 of these 19 cases was the two-stage revision ultimately successful.

Conclusions

Eradication of infection with ODPE in acute TKA infections is unpredictable; certain factors trend toward increased success but no firm algorithm can be offered. The success of two-stage revision for infection may be diminished after a failed ODPE.

Level of Evidence

Level III, retrospective comparative study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Despite major advances in both surgical techniques and perioperative management, deep infection after TKA remains a persistent and troubling complication. A recent study of the Medicare population revealed an incidence of infection of 1.55% in the first 2 years after TKA [12]. The Nationwide Inpatient Sample database indicates 25% of revisions are performed for management of infection [1]. This results in infection being the most common indication for revision TKA in the United States.

For many physicians and patients, treating an infected TKA with open débridement and polyethylene liner exchange (ODPE) rather than two-stage reimplantation is an attractive option. One study suggests lower morbidity and retention of well-fixed primary components are reasons for choosing ODPE [13]. Infection eradication with ODPE, however, has generally not approached the success rate associated with formal two-stage reimplantation [3, 8, 9]. Control of infection with ODPE is traditionally linked to various factors, including host comorbidities, virulence of the infecting organism, and timing of the infection in relation to the original surgery [10, 19]. Other studies have noted shorter duration of symptoms such as pain or swelling, absence of a draining sinus tract, or well-fixed components as factors favoring successful débridement [5, 14, 18]. Comparing studies of ODPE is often compromised by varying definitions of infection, complex antibiotic regimens, and differing criteria for failure of treatment [15]. However, if a treatment algorithm could be established, patients who have low probability of retaining the prosthesis could be counseled accordingly and proceed directly with two-stage revision.

The purpose of this study was to determine the overall success of ODPE in controlling infection in these populations and to examine which factors favored such success with particular attention to (1) the infecting organism; (2) duration of symptoms; and (3) timing of ODPE in relation to the original primary TKA.

Patients and Methods

We used two large total joint databases for this retrospective cohort study. The HealthEast Joint Registry (HEJR) is a community registry in St Paul with 11,449 primary TKAs registered between September 1991 and December 2008. The Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MVAMC) TKA database contains complete data on over 1100 TKAs since January 1994. We searched both databases from January 1994 to December 2008 for patients who had undergone TKA and subsequently developed a periprosthetic infection (PPI). PPI was defined as two or more positive cultures obtained by preoperative aspiration or intraoperative specimens or gross purulence surrounding the prosthesis at the time of surgery [2, 14, 18]. From these databases, we identified 44 patients (44 knees) who had undergone ODPE as the initial procedure to control infection. Seventeen knees were included from the HEJR database and 27 knees were from the MVAMC database. We could not account for any patients in the HEJR who underwent primary TKA in the HEJR capture area but were subsequently treated with ODPE outside of that area. However, the capture rate of this population is approximately 94% [7]. The capture of the MVAMC database approaches 100%. Patients who have had their primary TKA at the MVAMC have invariably undergone ODPE within the MVAMC system. Included within this population are patients who may have had a primary TKA elsewhere and were referred to the MVAMC for treatment of their acutely infected TKA. The average age of the study group was 70 years (range, 48–94 years) at the time of their index procedure and 71 years (range, 48–96 years) at the time of their ODPE. There were 35 males (79.5%) in the group and all patients presented with clinical symptoms associated with infection. The most common presenting symptom was an acute increase in pain (Table 1). The duration of symptoms ranged from 2 to 28 days with an average of 8.4 days from onset of symptoms to ODPE. Preoperative laboratory evaluation of most patients included white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (Table 1). In 27 patients, both CRP and ESR were tested before ODPE and were elevated. After identifying the study population, we followed the 44 patients for a minimum of 1 year (mean, 5 years; range, 1–9 years) after ODPE.

Table 1.

Preoperative presenting symptoms, signs, and serology

| Serologic test | Number of patients | Abnormal value |

|---|---|---|

| Serum white blood cell count | 44 | 22* (50%) |

| C-reactive protein | 32 | 31† (97%) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 29 | 29‡ (100%) |

| C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 27 | 27 (100%) |

| Presenting symptoms | ||

| Acute onset of pain | 28 (64%) | |

| Acute onset of swelling | 23 (52%) | |

| Active drainage | 16 (36%) | |

| Increased swelling and pain | 23 (52%) | |

* Greater than 10,000 white blood cell count; †reference range laboratory-dependent; ‡greater than 30 mm/hr.

An algorithm for treatment of the infected TKA was not standardized as a result of the retrospective nature of this study. The diagnosis of a PPI was confirmed using results of preoperative aspiration and/or intraoperative cultures. Twenty-seven patients (61%) had a positive aspiration. The remaining 17 knees were diagnosed by intraoperative cultures obtained at the initial ODPE. In eight patients, antibiotics were documented as being given before obtaining an aspiration or intraoperative cultures. Management decisions regarding the choice and timing of ODPE and the regimen of antibiotics were at the discretion of the surgeon and the infectious disease consultant. In all cases, operative reports confirmed that the total knee components were well fixed at the time of ODPE. There was no standardized antibiotic treatment regimen after ODPE. In general, patients were started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and then converted to an organism-specific antibiotic after culture results. Failure was defined as any reoperation performed for the control of infection or the need for lifetime antibiotic suppression.

We reviewed all patient charts to determine demographics (gender, age, comorbidities), duration of symptoms, time from index TKA to ODPE, infecting organism(s), additional operative procedures, and final outcome. We assessed patient comorbidity with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score [6] at the time of initial débridement and Charlson Comorbidity Index [4] calculated from preoperative evaluations. Serologic parameters (ESR, CRP) were not routinely available in all cases but were analyzed when available. Organisms were grouped into four groups: Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, other Gram-positives, and Gram-negatives.

The overall success of the ODPE in controlling infection was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. The overall cumulative revision rate was calculated based on the rate of failure and the timing of those failures. Specific statistical tests were used to determine which factors favored success of ODPE. Infecting organism and timing of the ODPE were compared between successes and failures using the Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test when the expected cell count was less than 5. The average duration of symptoms for the successes and failures were compared using the Student’s t-test with equal variances assumed resulting from Levene’s test for equality of variances. Other variables that we suspected might confound the relationship among these three factors and the success of the ODPE were considered. Gender, database, wound at presentation, ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Index for the successes and failures were compared again using the Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test when the expected cell count was less than 5. Average age was compared between successes and failures using Student’s t-test with equal variances assumed resulting from Levene’s test for equality of variances. None of these variables were associated with success or failure (Table 2) and therefore they did not confound the association among any of our three main variables of interest and success of ODPE. As a result of the small number of patients in our study, post hoc corrections were not made and a multivariate logistic regressions analysis was not performed.

Table 2.

Success of (ODPE) based on patient characteristics

| Patient characteristic | Success (n = 19) | Failure (n = 25) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 70.1 (13.1) | 69.1 (8.1) | 0.76 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.93 |

| Male | 15 (42.9%) | 20 (57.1%) | |

| Database | |||

| HealthEast | 7 (41.2%) | 10 (58.8%) | 0.83 |

| VAMC | 12 (44.4%) | 15 (55.6%) | |

| Timing of ODPE | |||

| Early (≤ 28 days from index procedure) | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) | 0.62 |

| Late (> 28 days from index procedure) | 14 (41.2%) | 20 (58.8%) | |

| Mean time to ODPE after symptoms began (SD) | 7.8 (5.8) | 8.8 (7.4) | 0.64 |

| Wound at presentation | |||

| Drainage | 7 (43.7%) | 9 (56.3%) | 0.95 |

| No drainage | 12 (42.9%) | 16 (57.1%) | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score | |||

| 2 | 6 (42.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.98 |

| 3 or 4 | 13 (43.3%) | 17 (56.7%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 or 1 | 14 (38.9%) | 22 (61.1%) | 0.22 |

| 2–5 | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | |

Results

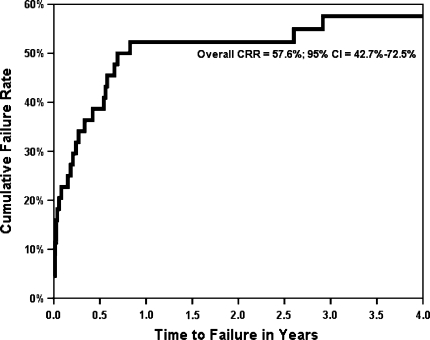

Twenty-five knees (56.8%) failed, two of which required chronic antibiotic suppression. In two cases, only one additional procedure was performed after the failed ODPE; one patient required a single repeat irrigation and débridement, whereas the other had an explant with placement of an antibiotic spacer but no revision components. In the remaining failures (21 knees), more than one additional procedure was performed (range, 2–9). After failure of the débridement, the majority of patients (19 of 21) were treated with an attempted two-stage revision, whereas two patients underwent multiple débridements. The average time from the initial ODPE to failure was 167 days (range, 0–1065 days) (Table 3). The cumulative revision rate was 58% at 4 years (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Final outcome after failure of ODPE

| Outcome | Knees (n = 25) |

|---|---|

| Two-stage revision TKA | 11 |

| Multiple débridements | 4 |

| Antibiotic spacer | 4 |

| Knee arthrodesis | 3 |

| Chronic suppression | 2 |

| Above-knee amputation | 1 |

ODPE = open débridement with polyethylene liner exchange.

Fig. 1.

The Kaplan-Meier survival curve reveals a 58% failure rate at 4 years from open débridement with polyethylene liner exchange.

Thirty-eight of the 44 knees (86%) were infected by a single organism and six knees were positive for multiple organisms with five of six growing a Staphylococcus species in addition to at least one additional organism (Table 4). In all cases with multiple organisms, infectious disease consultants identified a primary pathogen and a contaminant organism, typically diptheroids. Analysis of the groups based on infecting organism yielded no difference when comparing the risk of failure of ODPE to control the infection with the type of organism (Table 5). However, there was a trend toward a higher failure rate (p = 0.06) when looking specifically at S. aureus versus S. epidermidis. Seventy-one percent of S. aureus infections failed compared with 29% of knees infected with S. epidermidis. A retrospective power analysis determined we would need approximately 30 patients to reach a level of statistical significance for this large difference of failure rates between S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Comparison of knees infected with a single organism with knees having multiple organisms yielded no difference (p = 0.68) in failure rate based on control of infection. The number of knees infected with methicillin-resistant S. aureus in our study was low (n = 4) and no difference was found when comparing failure rates of patients infected with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus.

Table 4.

Organism cultured at aspiration or intraoperatively

| Organism | Number of cases (n = 44) |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 17 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 10 |

| Other Gram-positives | 13 |

| Gram-negatives | 4 |

Table 5.

Success of ODPE based on organism

| Organism | Success (n = 19) | Failure (n = 25) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 5 (29.4%) | 12 (70.6%) | 0.22 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | |

| Other Gram-positive organisms | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.5%) | |

| Gram-negative organisms | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | |

| Staphylococcus species | |||

| S. aureus | 5 (29.4%) | 12 (70.6%) | 0.06 |

| S. epidermidis | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) | |

| MRSA versus MSSA | |||

| MRSA | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0.54 |

| MSSA | 3 (23.1%) | 10 (76.9%) | |

| MRSA | |||

| Yes | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0.99 |

| No | 17 (42.5%) | 23 (57.5%) | |

ODPE = open débridement with polyethylene liner exchange; MRSA = methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MSSA = methicillin-susceptible S. aureus.

There was no difference in outcome based on duration of symptoms. The duration of symptoms for the successfully treated group averaged 7.8 days (range, 2–21 days) before ODPE, whereas the failure group averaged 8.8 days (range, 2–28 days; p = 0.64)

We found no difference (p = 0.62) in the failure rate if ODPE was performed less than 28 days from the index surgery (Table 4). The average duration of time from the patient’s index procedure to ODPE was 396 days (range, 7–2543 days). Ten knees were diagnosed with infection and underwent ODPE less than 28 days from their index procedure.

The patient-specific characteristics were similar in the successfully treated and the failed groups (Table 2). The failure rates between the two databases were essentially identical (59% versus 56%) and no association was found between health status and successful ODPE.

Discussion

Two-stage reimplantation for the treatment of TKA PPI is generally acknowledged as the most definitive treatment of this difficult and costly complication [8, 9, 11, 20]. However, the substantial morbidity associated with two major operations separated by a lengthy interval of intravenous antibiotics must be acknowledged. Both patients and surgeons often view ODPE as an acceptable option in the setting of acute PPI. We sought to determine the overall success of ODPE in controlling infection and to examine the role played by the factors of (1) the infecting organism; (2) duration of symptoms; and (3) timing of ODPE in relation to the original primary TKA.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the ODPE procedure itself was not standardized and individual surgeons may have differed on what constitutes appropriate débridement and irrigation. Second, the timing and choice of antibiotic administration was often comanaged with infectious disease consultants without a standardized protocol. Treatment trends could not be analyzed for antibiotic use because each regimen was tailored to the patient based on culture results, allergies, and ability to manage home intravenous antibiotics. Third, selection bias exists in that many surgeons will choose ODPE as an option in the most acute cases with the most sensitive organisms, a bias that would only reinforce the conclusions of the study. Of course, the possibility that this option was chosen secondary to patient comorbidities or anticipated life expectancy must also be considered. Fourth, although the chart review and patient followup were thorough, defining onset of symptoms and the regimen of antibiotics was difficult even with complete office and hospital records. Finally, the cohort is relatively small and larger numbers may have allowed us to assign importance to the factors studied. However, the study population is larger than most that have looked at this issue (Table 6), the limitations noted are inherent to all retrospective studies in this area, and the combined databases may afford us a more realistic picture of how this problem is addressed in the orthopaedic community outside a single research institution.

Table 6.

Selected prior published studies on ODPE for infected TKA

| Authors/study | Subjects (knees) | Mean followup (years) | Average duration of symptoms success/failure (days) | Average time from index to débridement (range) | Number of knees less than 1 month from index surgery | Number infected with Staphylococcus aureus | Failure rate for S. aureus | Successful salvage of components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burger et al. [3] | 39 | 4.1 | 4.4/117 | N/A | N/A | 20 (51%) | 85% | 17.9% (7/39 knees) |

| Deirmengian et al. [5] | 31 | 4.0 | 7.6/10.1 | 24 months (0.5-84) | N/A | 13 (42%) | 92% | 35% (11/31 knees)* |

| Mont et al. [15] | 24 | 5.0 | 9.9/26† | 23 months (6-71)‡ | 10 (42%) | 12 (50%) | 8% | 83% (20/24 knees)§ |

| Hartman et al. [10] | 33 | 4.5 | 18.6/10.5 | 11 months (N/A) | 11 (33%) | 13 (39%) | 69% | 39% (13/33 knees) |

| Schoifet and Morrey [16] | 31 | 8.8 | 21/36 | N/A | 9 (29%) | 16 (52%) | 88% | 23% (7/31 knees) |

| Gardner et al. [current study] | 44 | 5.0 | 7.8/8.8 | 13 months (0.2-84) | 10 (23%) | 17 (39%) | 71% | 57% (25/44 knees) |

* Five of 11 continued on suppressive antibiotics for control of infection; †data only available for 14 of 24 knees; ‡this represents time from index surgery to débridement for 14 of the 24 knees; the other 10 knees were less than 1 month from index; §inclusion criteria were less than 30 days from index or less than 30 days of symptoms and multiple débridements were performed; ODPE = open débridement with polyethylene liner exchange; N/A = data not available within the study.

There is mounting evidence that PPI infections with certain Staphylococcus species have a poor prognosis. Brandt et al. reported 69% of total joints infected with S. aureus failed within 2 years and those débrided greater than 2 days after the onset of symptoms were associated with higher failure rate [2]. In a more recent study, Deirmengian et al. [5] reviewed 31 infected TKAs and reported a 92% failure rate in those with S. aureus compared with 44% for other Gram-positive organisms. They recommended removal of the prosthesis in cases of S. aureus infection [5]. Although the findings in our study also trend toward higher failure rates for S. aureus versus S. epidermidis, we could not confirm this trend with limited numbers of patients.

A longer duration of symptoms (pain, swelling, or drainage) before débridement has been correlated with increased probability of failure. Schoifet and Morrey reported 31 infected TKAs and noted the duration of symptoms averaged 15 days longer in those patients who failed ODPE [16]. In a retrospective review of 39 infected TKAs, Burger et al. reported a success rate of only 17.9% after irrigation and débridement [3]. The average duration of symptoms for the failed knees was 117 days versus 4 days for the successfully treated knees. A longer duration of symptoms, presence of a sinus tract, and radiographic signs of infection strongly correlated with failed débridement [3]. In a 2006 review of 99 PPIs, Marculescu et al. noted duration of symptoms greater than 8 days correlated with increased risk of failure of open débridement [14]. We found an average duration of symptoms of 8.4 days, and no patient had symptoms longer than 28 days before undergoing an ODPE. An understandable selection bias occurs as the result of surgeons attempting ODPE only in cases in which the PPI is believed to be acute. Given the poor results with ODPE in treating chronic infections [3, 17], most surgeons in our series undoubtedly used two-stage reimplantation when managing a patient with prolonged symptoms.

Multiple studies have also described a correlation between the duration of time from the index primary TKA surgery to ODPE. In an evaluation of 33 infected TKAs, Hartman et al. found a decrease in success of ODPE when performed greater than 4 weeks from the index surgery [10]. Other authors have established lower success rates with débridement performed greater than 2 weeks after the index procedure [19]. The average time from index surgery to ODPE, in our study, was 396 days (range, 7–2543 days) with 77% of knees (34 of 44) undergoing débridement greater than 4 weeks from the index procedure. In our study, there was no difference in the success rate if ODPE was performed less than 28 days from the index surgery.

When managing an infected TKA, the perception may exist that little harm results from an attempt at ODPE even if the success rate is low. In our series, 19 of the 25 failures were treated with an attempted two-stage revision as the next step after failed ODPE. In 11 of the 19, the end result was successful reimplantation of revision components. In the other eight patients, revision components were not reimplanted because of persistent infection or diminished health status. The final outcome of these eight patients resulted in four patients being left with antibiotic spacers in place, three fusions, and one above-knee amputation. Our success rate of two-stage reimplantation after failed ODPE is lower than published reports of two-stage reimplantation as the initial treatment [8, 9, 11]. This suggests attempting to salvage the implant with ODPE may ultimately lower the chance of successful reimplantation. One possible explanation is ODPE may simply delay the inevitable explantation, allowing the infection to become deep-seated or more chronic in nature.

Our intended goal was to identify specific characteristics of primary TKA infection in which ODPE routinely resulted in control of the infection. Although no firm algorithm could be established, certain factors do appear to favor successful control of infection with ODPE. Periprosthetic joint infections with S. epidermidis were controlled in 70% of patients after a single débridement and polyethylene exchange. This is in contrast to prosthetic infections with S. aureus in which nearly three of four patients required additional procedures to clear the infection. However, choosing to proceed with ODPE as the initial treatment when managing a PPI of the knee may ultimately decrease the chance of controlling the infection with two-stage reimplantation if the infection persists. The authors would continue to recommend ODPE in situations in which the infection is caused by a favorable organism such as S. epidermidis, the symptoms have been present only a short time, the infection has occurred within 4 weeks of the primary TKA, and the host is healthy. In less clearly defined situations, the decision to proceed with ODPE should be made only after weighing all of these factors carefully with the patient.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the Minneapolis Veterans Administration Medical Center and the HealthEast Hospitals, St Paul, MN, USA.

References

- 1.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Chiu V, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;468:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0945-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt CM, Sistrunk WW, Duffy MC, Hanssen AD, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Osmon DR. Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection treated with débridement and prosthesis retention. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:914–919. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger RR, Basch T, Hopson CN. Implant salvage in infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;273:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and Validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deirmengian C, Greenbaum J, Stern J, Braffman M, Lotke PA, Booth RE, Lonner JH. Open débridement of acute Gram-positive infections after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;416:129–134. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000092996.90435.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dripps RD. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology. 1963;24:111. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gioe TJ, Killeen KK, Mehle S, Grimm K. Implementation and application of a community total joint registry: a twelve year history. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1399–1404. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman RT, Scuderi GR, Insall JN. Two-stage reimplantation for infected total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;331:118–124. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199610000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haleem AA, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD. Mid-term to long-term followup of two-stage reimplantation for infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:35–39. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000147713.64235.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartman MB, Fehring TK, Jordan L, Norton HJ. Periprosthetic knee sepsis: the role of irrigation and débridement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;273:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insall JN, Thompson FM, Brause BD. Two-stage reimplantation for the salvage of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1087–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozick KJ, Berry D, Parvizi J. Prosthetic joint infection risk following TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;468:52–56. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1013-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leone JM, Hanssen AD. Management of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2335–2348. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200510000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marculescu CE, Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Steckelberg JM, Harmsen SW, Mandrekar JN, Osmon DR. Outcome of prosthetic joint infections treated with débridement and retention of components. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:471–478. doi: 10.1086/499234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mont MA, Waldman B, Banerjee C, Pacheco IH, Hungerford DS. Multiple irrigation, débridement, and retention of components in infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:426–433. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoifet SD, Morrey BF. Treatment of infection after total knee arthroplasty by débridement with retention of the components. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1383–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segawa H, Tysukama D, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty-one infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1434–1445. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tattevin P, Cremieux AC, Pottier P, Huten D, Carbon C. prosthetic joint infection: when can prosthesis salvage be considered? Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:292–295. doi: 10.1086/520202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teeny SM, Dorr L, Murata G, Conaty P. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty. Irrigation and débridement versus two-stage reimplantation. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:35–39. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windsor RE, Insall JN, Urs WK, Miller DV, Brause BD. Two-stage reimplantation for the salvage of total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]