Abstract

Background

Fibular hemimelia is partial or total aplasia of the fibula; it represents the most frequent congenital defect of the long bones. It usually is associated with other anomalies of the tibia, femur, and foot.

Questions/purposes

We reviewed 32 patients with Type III fibular hemimelia treated by successive lower limb lengthening and deformity correction using the Ilizarov method. We had three aims; first, to analyze complications, including the need for reoperation. The second was to assess knee and ankle function, specifically addressing knee ROM and stability and function of the foot and ankle. The third was assessment of overall patient satisfaction.

Patients and Methods

Thirty-two patients underwent 56 tibia lengthenings and 14 ipsilateral femoral lengthenings. Their mean age and mean functional leg-length discrepancy at initial treatment were 6.7 years and 6.2 cm, respectively. Activity level, pain, patient satisfaction with function, pain, and cosmesis, complications, and residual length discrepancy were assessed at the end of treatment.

Results

The mean number of surgeries was six per case. The healing index was 44.9 days/cm. Although complications were observed during 60 lengthenings (82%), the highly versatile system overcame most of them. Nearly equal limb length and a plantigrade foot were achieved by 16 patients. For two patients, a Syme’s amputation was performed. The outcome was considered satisfactory in 17 patients (53%) and relatively good in eight patients (25%).

Conclusions

The Ilizarov technique has satisfactory results for treatment of Type III congenital fibular hemimelia and can be considered a good alternative to amputation.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Fibular hemimelia or congenital longitudinal deficiency of the fibula is not an isolated anomaly but rather a spectrum of dysplasia of the limb. The clinical spectrum includes partial or complete absence of the fibula with variable other anomalies, including tibial shortening and angular deformities, ball and socket ankle, tarsal anomalies, absence of the lateral rays of the foot, femoral shortening, proximal femoral focal deficiency, and occasionally hand anomalies. The major functional deficits are severe shortening of the extremity and equinovalgus deformity of the ankle [4, 13, 15, 21].

There are several classifications for fibular hemimelia. In our center, we use a modified Dalmonte classification, which is simple and comprehensive [1, 18]. The classification is related to the structural features of the fibula. Type I is evidence for mild fibular and tibial shortening; in this type, there is no significant associated angular deformities of the femur, foot, tibia, or knee instability. There may be a ball and socket ankle or missing foot rays. Type II is characterized by severe fibular and tibial shortening without a functional lateral malleolus. Ankle instability, missing one or two rays, equinovalgus foot deformity knee instability, and valgus deformity of the knee are frequent associations. Type III is the most severe type of fibular hemimelia and is characterized by complete absence of the fibula, severe tibial deformity and shortening, and an equinovalgus foot (Fig. 1). The associated femur deformities include shortening, knee instability, and valgus deformity.

Fig. 1.

Type III fibular hemimelia is shown in this radiograph.

Treatment must be individualized based on the severity of the deformity and on the presence or absence of associated deformities. In our countries, parents are reluctant to accept the traditional North American approach to the more severe forms, which is Syme’s amputation. The introduction of the Ilizarov technique has changed management of fibular hemimelia a great deal. Multiple surgical procedures are necessary to attempt to provide a stable ankle, plantigrade foot, and equal limb lengths in a normal mechanical axis [3, 4, 6, 13, 15, 21].

This study was designed to assess use of the Ilizarov method for limb-length inequality and deformity correction in patients with Type III fibular hemimelia. We had three aims; first, to analyze complications, including the need for repeat hospitalization for reoperation. The second was to assess knee and ankle function, specifically addressing knee ROM and stability and plantigrade function and ROM of the foot and ankle. The third was assessment of overall satisfaction including freedom from pain, degree of activity, and subjective patient satisfaction with the result.

Patients and Methods

This is a retrospective study. Patients were selected from the hospital database of a total of 190 patients with fibular hemimelia treated from 1981 to 2006; 93 had Type III hemimelia according to the modified Dalmonte classification [6]. Forty of these 93 patients had reached skeletal maturity at the time of revision; 36 patients were included in the study and four patients were lost to followup. The patients included in the study were those with Type III fibular hemimelia who refused any form of amputation and were willing to do limb reconstruction and lengthening procedures. Of the 32 patients available for followup, 12 were females and 20 were males. At initial treatment, all had shortening and associated deformities of the lower limbs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of patients who had limb lengthening

| Parameters | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Age at initial presentation | |

| 1 day–1 year | 4 |

| 1 year–3 years | 15 |

| 3 years–6 years | 7 |

| > 6 years | 6 |

| Side | |

| Right | 20 |

| Left | 12 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 12 |

| Male | 20 |

| Length discrepancy at initial presentation | |

| < 3 cm | 6 |

| 3–6 cm | 15 |

| > 6 cm | 11 |

| Associated deformities | |

| Tibial bowing | 30 |

| Ball and socket joint | 20 |

| Equinovalgus foot | 20 |

| Lacked one or more lateral rays | 12 |

| Femoral shortening | 18 |

| Proximal femoral focal deficiency | 2 |

| Valgus knee | 4 |

Amputation had been recommended first for 12 patients, but the patients’ families refused and opted for Ilizarov lengthening. All cases receiving Ilizarov treatment were as planned by Catagni et al. [6] for management of Type III fibular hemimelia. The first stage addresses foot deformities as early as possible followed by limb lengthening when the patient is at the beginning of school age. The final stages attempt to further equalize limb length and correct other deformities as the patient approaches skeletal maturity.

Sixty-eight segments in 20 right lower limbs and 12 left lower limbs sustained successive lengthening in 12 female and 20 male patients. Twenty-four tibias had two-stage lengthening, eight had one stage, and 14 had ipsilateral femoral lengthening. Twelve patients had bifocal tibial osteotomy for lengthening and/or correction of deformities. Twelve patients lacked one or more lateral rays of the foot and eight of these patients also had associated femoral shortening. Twenty patients had an equinovalgus foot, 20 had a ball and socket joint, four had an associated valgus knee, and 18 had femoral shortening. The mean age of the patients was 6.7 years (range, 3–16 years), and the mean discrepancy was 6.2 cm (range, 4–10 cm) at the time of initial treatment. The mean followup was 9 years (range, 7–16 years).

Foot deformities were treated first by transcalcaneotibial pins after soft tissue release and excision of fibular anlage, tendon lengthening (including the tendoAchilles lengthening and peroneal tendon lengthening), or an Ilizarov foot extension to correct the foot deformity using the constrained frame.

To facilitate the stage of limb lengthening, the external fixator is designed and assembled preoperatively. A hybrid technique of bone fixation (using wires and half pins) and extension of the frame to the foot for lengthening are required to protect the foot from additional deformity when we plan lengthening greater than 6 cm (Fig. 2). Also, Ilizarov foot extension was the method used to correct foot deformities in 10 patients. Bifocal tibial lengthening was helpful for eight patients to shorten the time and enhance consolidation. Femoral extension of the frame for simultaneous femoral lengthening and knee protection was required for 14 patients [6, 11, 14, 16].

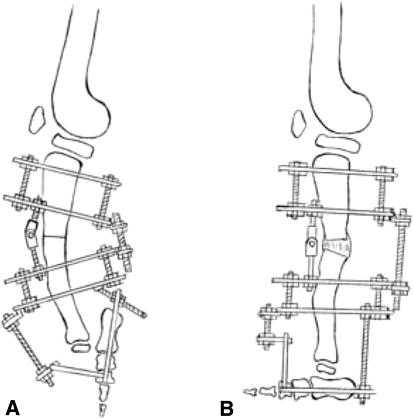

Fig. 2.

A–B The frame for leg lengthening and procurvatum correction was preassembled with foot fixation and simultaneous equinus correction. The diagrams show the frame (A) before and (B) after deformity correction.

Postoperative assessment was performed by two of us (MR, NAE) who were not the primary surgeons in any procedures. Functional leg-length discrepancy was assessed using calibrated wooden blocks [6]. Blocks were placed under the shortened limb until leveling of the pelvis was achieved. Preoperative and followup long-leg standing films were used to assess the overall anatomy of the affected lower extremity. These films permit use of the contralateral side as a control for measuring limb-length discrepancies, mechanical axis deviations, and anatomic axes. Clinic visits were scheduled weekly during the latent period and distraction phase, monthly in the consolidation phase, and nearly every 6 months thereafter for a lengthy followup with a mean of 9 years (range, 7–16 years). Outpatient care included physiotherapy, care of pin-site infection, device adjustment, and evaluation of bone alignment and consolidation.

At the end of the followup, we assessed the outcome by addressing the activity level which was graded from 0 to 3 (0 = no restriction, 1 = mild restriction with strenuous activity, 2 = moderate limitation of activity, 3 = severe limitation of activity). The level of pain was graded from 0 to 4 and patients were asked to describe their level of satisfaction with the procedure regarding function, pain, and cosmesis. Complications, including the residual length discrepancy, were documented (Table 2) [13].

Table 2.

Review of postoperative details of the patients who had limb lengthening

| Parameters | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Activity level | |

| 0 no restriction | 0 |

| 1 mild restriction with strenuous activity | 4 |

| 2 limitation of activity | 20 |

| 3 severe limitation of activity | 8 |

| Level of pain | |

| 0 no pain | 12 |

| 1 any pain, even after strenuous activity | 12 |

| 2 mild pain | 4 |

| 3 moderate pain | 4 |

| 4 severe pain | 0 |

| Satisfaction (subjective patient satisfaction regarding function, pain, and cosmesis) | |

| Yes | 24 |

| No | 8 |

| Residual length discrepancy at the end of treatment | |

| Less than 1 cm | 16 |

| 1–3 cm | 10 |

| Greater than 3 cm | 6 |

| Complications | |

| Knee subluxation | 4 |

| Decrease in range of knee movement | 12 |

| Equinus deformity | 8 |

| Valgus deformity | 8 |

| Pathologic fractures | 6 |

Results

The mean lengthening achieved was 13 cm (range, 8–17 cm). Limbs were equalized to within 1 cm in 16 of the 32 (50%) patients. The mean duration of application of the external fixator was 11.2 months (range, 5.8–20.8 months) and the mean healing index (total treatment time in days per centimeter of lengthening) was 44.9 days (range, 36–50 days).

Postoperative complications were numerous and included flexion contractures, subluxation of the knee, valgus and procurvatum deformities, stiff joints, pin-site infection, pressure sores, aesthetic concerns, transient paresthesiae, and depression, but most could be resolved. The mean number of hospital admissions for these patients was 4.1 (range, 2–9), and the mean length of hospital stay was 47.0 days (range, 15–131 days). Reasons for subsequent hospital admissions included modifications to the frame, correction of encountered problems, treatment of pin-site infections, and removal of the fixator. Six pathologic fractures in the involved limb after removal of the fixator required reapplication of the Ilizarov frame.

At the end of the followup, eight patients had achieved full ROM of the knee and 12 had achieved flexion greater than 90o with lack of extension less than 10o. Four patients had knee subluxation with knee stiffness. A plantigrade foot with good range of movement was achieved in 16 feet. Sixteen patients had residual foot deformities. Eight patients sustained equinus deformities of 5° and 7° without instability or subluxation of the ankle, whereas the other eight had valgus angulations of the ankle.

The outcome on long-term followup was considered to be satisfactory in 17 patients (53%). Eight patients (25%) who are unlikely to require additional surgery were still wearing braces or shoe raises for daily activities at their latest outpatient visit. Two patients (6%) recently began a second lengthening procedure to correct residual leg-length discrepancy, and two (6%) had late Syme’s amputation of a functionless and poorly cosmetic limb. Three patients (9%) will need corrective osteotomy for valgus deformity and residual discrepancy for them to achieve better satisfaction. In addition, three patients who were satisfied asked for scar revision to improve the appearance of cosmetically uncomfortable skin.

Discussion

Management of Type III fibular hemimelia continues to be controversial [15]. Our rationale from the current study was to assess the results of using the Ilizarov technique in this group of patients and to document the complication rate and incidence of reoperation. We hoped to assess if the long period of treatment and high rate of complications associated with Ilizarov application and preservation of the limb outweigh the results of amputation and use of below-knee prostheses [2, 9, 13, 19, 21].

Naudie et al. [15] recommended clearly explaining to the families that amputation is a reconstructive procedure and should not be considered a failure of treatment. When families refuse amputation, however, we must respect their decision, but the short-term and long-term complications of repeated lengthening must be clearly explained.

The limitations of our study include that the interobserver and intraobserver reliabilities of the measured outcome were not assessed. Our assessment of the function and patient satisfaction are not validated. Also the study group is highly selected; the criteria for inclusion are variable and subjective. The indication for surgery in some patients is psychologic and not based on traditional criteria. There is concern for the families for the psychologic factor regarding the choice of treatment and for the patient during the course of treatment, and we did not precisely address that in our methods. This does not distract us from our primary conclusion that preservation of the limb outweighs the amputation.

This study showed that good results can be obtained with limb lengthening and deformity correction with the Ilizarov method. More than half of our patients were satisfied and most achieved limb-length equality, are able to walk, have minimal pain, and are quite active. With gradual distraction, good length was obtained with fewer problems. Moreover, the highly versatile system might overcome most complications. This is true even though amputation was the end result for two patients.

We studied our lengthening group to determine which preoperative factors were associated with a good result. Valgus angulations of the ankle seem to be a predictor of a poor result. Of eight patients with ankle valgus, four were not satisfied and the others had pain and/or activity restrictions.

Our results coincide with those of other authors having obtained good results with repeated lengthening. In a retrospective comparative study, Jawish and Carlioz [12] reported good correction of the foot in 60% of cases of fibular hemimelia treated by lengthening. Miller and Bell [14] reported no serious complications and no late amputations in 12 cases that underwent lengthening by the Ilizarov technique. Catagni et al. [6] prefer to preserve the foot and use repeated lengthening and correction for limb-length discrepancies, angular and rotational deformities, and foot and ankle deformities. Hany [8] achieved satisfactory results in three of four patients with Type II fibular hemimelia in his series. Walker et al. [20] stated that patients who were treated with lengthening started out with more residual foot rays and more fibular preservation than the amputees. However, all these authors agreed that there are many potential problems, obstacles, and complications associated with repeated lengthening.

Patients who underwent amputation after several failed attempts at salvage were at high risk for emotional problems [9, 10]. Determining which patients may fare better with immediate amputation is important. Generally, these are patients with a nonfunctional foot or a limb-length discrepancy greater than 20 to 30 cm. For the severely affected child with a predicted limb-length discrepancy greater than 25 cm at maturity and with a poor foot and ankle, amputation generally is thought to be the best option [5]. For patients with less severely affected limbs, particularly those with a predicted limb discrepancy of 10 cm or less and with a foot with three or more rays, which can be made plantigrade, limb reconstruction is recommended. Controversy remains regarding the best way to manage children with an intermediate deformity [5]. We agree [16] that amputation should be the treatment of last resort if the limb can be safely and reliably lengthened, reconstructed, and preserved. Whenever feasible, efforts should be made to involve the child in the decision-making process, especially when an ablative procedure such as amputation is being considered.

Some authors do not believe cost should play a deciding role in determining the treatment plan [13]. Despite higher initial costs resulting from greater medical/surgical intervention, other authors have reported if the lifetime costs of prostheses are included, lengthening is less expensive than amputation [2, 13, 16].

Despite this initial success, the long-term results of lengthening can be unpredictable. Tibiae that have been lengthened to correct a congenital deficiency subsequently can have a slowed growth rate [17]. Also, substantial progressive angular (osseous) deformities can occur after lengthening for fibular hemimelia [7].

Although lengthening in Type III fibular hemimelia is difficult and requires multiple surgeries, elongation with alignment and foot correction using the modified Ilizarov technique may offer an alternative to amputation. New studies, highly specialized centers, and professional staff are required to minimize the potential complications.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

This work was performed at Lecco General Hospital, Lecco, Italy.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Achterman C, Kalamchi A. Congenital deficiency of the fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61:133–137. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.61B2.438260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basbozkurt M, Yildiz C, Kömürcü M, Demiralp B, Kürklü M, Atesalp AS. Management of fibular hemimelia with the Ilizarov circular external fixator] [in Turkish. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2005;39:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birch JG, Walsh SJ, Small JM, Morton A, Koch KD, Smith C, Cummings D, Buchanan R. Syme amputation for the treatment of fibular deficiency: an evaluation of long-term physical and psychological functional status. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1511–1518. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd HB. Amputation of the foot with calcaneotibial arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1939;21:997–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradish CF. Management of fibular hemimelia[in German] Orthopade. 1999;28:1034–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catagni MA, Bolano L, Cattaneo R. Management of fibular hemimelia using the Ilizarov method. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22:715–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng JC, Cheung KW, Ng BK. Severe progressive deformities after limb lengthening in type-II fibular hemimelia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:772–776. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B5.8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hany H. Management of fibular hemimelia by the Ilizarov technique. Egyptian Orthop J. 1999;34:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herring JA. Symes amputation for fibular hemimelia: a second look in the Ilizarov era. Instr Course Lect. 1992;41:435–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herring JA, Barnhill B, Gaffney C. Syme amputation: an evaluation of the physical and psychological function in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilizarov GA. The tension-stress effect of the genesis and growth of tissues: Part 1. The influence of stability of fixation and soft-tissue preservation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;238:249–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jawish R, Carlioz H. Conservation of the foot in the treatment of longitudinal external ectromelia. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1991;77:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy JJ, Glancy GL, Chang FM, Eilert RE. Fibular hemimelia: comparison of outcome measurements after amputation and lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1732–1735. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller LS, Bell DF. Management of congenital fibular deficiency by Ilizarov technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:651–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naudie D, Hamdy RC, Fassier F, Morin B, Duhaime M. Management of fibular hemimelia: amputation or limb lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:58–65. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B1.6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel M, Paley D, Herzenberg JE. Limb-lengthening versus amputation for fibular hemimelia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:317–319. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200202000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma M, MacKenzie WG, Bowen JR. Severe tibial growth retardation in total fibular hemimelia after limb lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:438–444. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanitski DF, Stanitski CL. Fibular hemimelia: a new classification system. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:30–34. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomás-Gil J, Valverde Belda D, Chismol-Abad J, Valverde-Mordt C. Complete fibular hemimelia: a long-term review of four cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker JL, Knapp D, Minter C, Boakes JL, Salazar JC, Sanders JO, Lubicky JP, Drvaric DM, Davids JR. Adult outcomes following amputation or lengthening for fibular deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:797–804. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarzycki D, Jasiewicz B, Kacki W, Koniarski A, Kasprzyk M, Zarzycka M, Tesiorowski M. Limb lengthening in fibular hemimelia type II: can it be an alternative to amputation? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:147–153. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000184949.00546.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]