Abstract

Background

Relatively few studies have examined gender differences in the effectiveness of specific behavioral or pharmacologic treatment of alcohol dependence. The aim of this study is to assess whether there were gender differences in treatment outcomes for specific behavioral and medication treatments singly or in combination by conducting a secondary analysis of public access data from the national, multi-site NIAAA-sponsored COMBINE study.

Methods

The COMBINE study investigated alcohol treatment among eight groups of patients (378 women, 848 men) who received Medical Management with 16 weeks of placebo, naltrexone (100mg/day), acamprosate (3 grams/day), or their combination with or without a specialist-delivered Combined Behavioral Intervention. We examined efficacy measures separately for men and women, followed by an overall analysis that included gender and its interaction with treatment condition in the analyses. These analyses were done to confirm whether the findings reported in the parent trial were also relevant to women, and to more closely examine secondary outcome variables that were not analyzed previously for gender effects.

Results

Compared to men, women reported a later age of onset of alcohol dependence by approximately 3 years, were significantly less likely to have had previous alcohol treatment; and drank fewer drinks per drinking day. Otherwise, there were no baseline gender differences in drinking measures. Outcome analyses of two primary (percent days abstinent and time to first heavy drinking day) and two secondary (good clinical response and percent heavy drinking days) drinking measures yielded the same overall pattern in each gender as that observed in the parent COMBINE study report. That is, only the naltrexone by behavioral intervention interaction reached or approached significance in women as well as in men. There was a naltrexone main effect that was significant in both men and women in reduction in alcohol craving scores with naltrexone-treated subjects reporting lower craving than placebo- treated subjects,

Conclusions

This gender-focused analysis found that alcohol-dependent women responded to naltrexone with COMBINE’s Medical Management, similar to the alcohol-dependent men, on a wide range of outcome measures. These results suggest that clinicians should feel comfortable prescribing naltrexone for alcohol dependence in both men and women. In this study, it is also notable that fewer women than men reported receiving any alcohol treatment prior to entry into the COMBINE study. Of note, women tend to go to primary health care more frequently than to specialty substance abuse programs for treatment, and so the benefit we confirm for women of the naltrexone and medical management combination has practical implications for treating alcohol-dependent women.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past five decades the prevalence of alcohol use disorders in the United States has narrowed such that alcohol abuse and dependence are now only twice as prevalent in men than in women [Keyes, Grant and Hasin, 2008; Grucza, Bucholz, Rice, and Bierut, 2008]. This stands in contrast to the 1980’s when the prevalence was approximately five times more common among men than women [ECA; Robins and Regier 1992]. Findings from two cross-sectional analyses of drinking across birth cohorts demonstrated little variation in lifetime drinking histories among men from different birth cohorts compared at similar ages. By contrast, women born between 1954 and 1963 had significantly more lifetime drinking than those born in the previous cohort of women between 1944–1953 [Grucza, Bucholz, Rice, and Bierut, 2008]. Among those who drank, women in the latter birth cohort were also at a significantly higher risk of developing alcohol dependence than those in the earlier birth cohort [Grucza, Bucholz, Rice, and Bierut, 2008]. Similarly, women born between 1944 and 1953 were at greater risk of lifetime alcohol use compared with the immediately preceding cohort born between 1934–1943 [Grucza, Bucholz, Rice, and Bierut, 2008]. Evidence for the convergence of lifetime drinking rates as well as alcohol use disorders for women compared to men is also emerging internationally demonstrated across a number of quantity and frequency measures [Stewart et al in Guilford book; Kraus, Bloomfield et al, 200; Roche and Deehan, 2002].

The increasing lifetime prevalence of drinking and alcohol use disorders among more recent birth cohorts raises clinical and public health concerns given the enhanced vulnerability among girls and women to the adverse medical, psychiatric, and social consequences of drinking [Greenfield et al, 2007; Gentilello et al, 2000; Piazza et al, 1989; Randall et al, 1999]. Women with alcohol dependence are more sensitive than alcohol dependent men to medical consequences such as liver disease, malnutrition, anemia, ulcers, hypertension, and brain atrophy [Stewart et al, 2009; Frezza et al, 1990; Mann et al, 2005]. In spite of these adverse consequences, women are less likely to enter alcohol treatment over the lifetime [Dawson, 1996]. However, while women may be less likely to enter alcohol treatment, among men and women receiving alcohol treatment, gender itself is not necessarily a predictor of outcome [Greenfield et al, 1998; Greenfield et al, 2007; Green et al, 2004]. However, relatively few studies have examined gender differences in the effectiveness of specific behavioral or pharmacologic treatment of alcohol dependence.

Biological studies suggest sex-specific neuroendocrine effects of medications, such as naltrexone on the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis [Kiefer et al, 2005] and on salivary cortisol [Klein et al, 2000]. While these findings suggest that naltrexone could be differentially effective in men and women, gender differences in response to oral naltrexone have shown mixed results [Pettinati et al, 2008; Baros et al, 2008; O’Malley, et al, 2007]. A recent study of alcohol and cocaine dependent individuals treated with oral naltrexone at a dose of 150mg each day demonstrated that compared with placebo, men treated with naltrexone had reductions in cocaine and alcohol use and drug severity; however, this effect was not seen in women who had higher rates of cocaine and alcohol use and severity. In this same study, the addition of psychosocial treatment did not affect outcome for men or women [Pettinati et al, 2008]. Within this study sample, there were no clear predictors of treatment discontinuation in men, but women were more likely to discontinue naltrexone treatment due to nausea while in treatment [Suh et al, 2008]. A separate study of gender differences in naltrexone treatment outcomes among alcohol dependent women demonstrated varying results by the treatment outcome end-point examined [Baros et al, 2008]. For example, the effect sizes for naltrexone over placebo were the same for women and men for outcome measures such as percent days abstinent, percent heavy drinking days, and total standard drinks [Baros et al, 2008]. Only for men did the difference in treatment outcome between naltrexone and placebo reach statistical significance. The authors attributed this difference to the larger sample size of men compared with women. The authors found that effect sizes were larger for men than women for outcomes such as change in drinking from baseline to week 12 and drinks per drinking day, whereas women had improvement with naltrexone compared with placebo only in increasing days of continuous abstinence before a first drink. The authors concluded that gender differences in effect size for naltrexone over placebo in previous studies may be attributed to sample size and/or the outcome endpoint measured [Baros et al, 2008].

Two studies have enrolled women exclusively [Ponce et al, 2005; O’Malley et al., 2007]. In a study comparing usual care with and without naltrexone, the addition of naltrexone reduced drop-out rates and rates of drinking to intoxication and increased the rate of good clinical outcome among 100 alcohol dependent women [Ponce et al., 2005]. In a placebo controlled study, naltrexone did not significantly improve outcomes in the intent-to-treat sample of 103 alcohol dependent women, although naltrexone delayed the onset of subsequent drinking days among those who lapsed [O’Malley et al., 2007]. Using trajectory analyses, naltrexone, compared to placebo, reduced the chance for these women to be consistent drinkers. Although not statistically significant, the effect size was similar to findings in larger predominantly male sample [Gueorguieva et al, 2007]. Again, the authors discussed the small sample size as an explanation for the lack of statistical significance.

The largest study of behavioral and pharmacologic treatment outcomes of alcohol dependence is the COMBINE study (e.g, Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence), a randomized controlled trial conducted between 2001–2004 among 1383 recently abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. The study compared eight groups of patients who received medical management with 16 weeks of naltrexone at 100mg per day or acamprosate at 3 g/day, or both, and/or both placebos, with or without a combined behavioral intervention (CBI) [Anton et al, 2006]. A ninth group received CBI alone with no pills. The overall results of the COMBINE study showed that subjects receiving medical management with naltrexone, CBI or both had better drinking outcomes. There was no evidence of efficacy with acamprosate with or without CBI. Naltrexone or CBI alone with medical management had superior efficacy than any other combination of treatments. No combination of treatments was more efficacious than naltrexone or CBI alone in the presence of medical management. While the COMBINE study concluded that overall men had a slightly better outcome for percent days abstinent compared with women, gender did not significantly affect response to any of the treatments. However, the results were not presented in detail nor were conclusions drawn about treatment effects in women. The main trial outcome paper also did not report on gender differences at baseline or on secondary outcomes as a function of gender. In order to examine in more detail baseline gender differences in drinking histories as well as gender differences in outcomes to the specific treatments used in the COMBINE study, we conducted a secondary analysis of public access data from the COMBINE study. The aim of this study is to assess whether there were gender differences in treatment outcomes for specific behavioral and medication treatments singly or in combination. We sought to enhance our ability to evaluate treatment outcome for women by performing the analyses for treatment outcomes separately for women and men. We then followed with an overall analysis of the entire study, identical to that of the parent report, except that we included gender and its interaction in the analyses. We also examined additional outcome measures of relevance for providing a comprehensive assessment of treatment effects. We limited our study to the three-way factorial and did not include the therapy-only group (i.e., Cell 9).

METHODS

Participants

This report is a secondary analysis of the COMBINE Study (Anton et al., 2006). Eleven clinical research sites across the continental United States recruited subjects from participating treatment study sites, outside community treatment agencies, and by public advertisements. The overall COMBINE sample consisted of 1,383 adult participants (428 women and 955 men) who met the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth Addition (DSM-IV) criteria for alcohol dependence based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). Inclusion criteria included drinking an average weekly minimum of 14 drinks (females), or 21 drinks (males) with a minimum of two heavy drinking days (four or more drinks for females and five or more drinks for males per drinking day) within a 30-day period in the 90 days prior to the baseline screening; and abstinence for at least 96 consecutive hours and a score less than 8 on the revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar) (Sullivan, Sykora, Schneiderman, Naranjo, & et al., 1989). A standard drink was 0.5 ounce of absolute alcohol, equivalent to 10 ounces of beer, 4 ounces of wine, or 1.0 ounce of 100-proof liquor. Exclusion criteria included meeting DSM-IV criteria for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or any other psychiatric disorder for which the individual required current medications, opioid dependence or abuse within six months prior to baseline; current dependence on any drug except marijuana or nicotine; more than seven days of inpatient treatment for a substance use disorder in the 30 days prior to randomization; planned continued participation in any pre-occurring alcohol treatment during the treatment phase of the study; or abstinence from alcohol for more than 21 consecutive days prior to randomization. Participants also underwent a full physical examination, including a blood and urine test, to screen for pregnancy and medical issues that posed potential safety considerations.

Treatment Conditions and Assessments

An overview of the methods including assessments, randomization, medical and behavioral treatments in COMBINE are described in detail elsewhere (The COMBINE Study Research Group, 2003). Briefly, 1383 alcohol dependent patients were randomized to one of nine conditions. Eight groups of patients (378 women, 848 men) received Medical Management (MM) with 16 weeks of placebo or active naltrexone (100mg/day) and placebo or active acamprosate (3 grams/day or placebo), with or without a specialist-delivered Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI). A ninth group of patients received CBI only with no pills (n = 157) and is not included in the current report. The medical management intervention (Pettinatti et al., 2004) was a 9-session intervention delivered by a medical professional and focused on enhancing medication adherence and abstinence using a model that could be adapted by primary care settings. The Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (Miller, 2004) was delivered by alcohol specialists and incorporated components that have been found effective in alcohol dependence, including motivational enhancement therapy (Miller and Rolnick, 2002), cognitive-behavioral skills training (Kadden et al., 2002), encouragement of AA participation (Humphreys et al., 2004) and community reinforcement (Meyers and Smith, 1995). CBI used a flexible menu of session topics to address issues that the therapist and participant identified. Participants could attend up to 20 sessions, with the number and content determined by the patient and therapist in concert. Research assistants obtained daily estimates of drinking using the Time-Line follow-back interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) and measures of craving at weeks corresponding to MM appointments. Additional assessments were administered at intake/baseline and at weeks 8 and 16.

Statistical Analyses

The original study was designed to provide sufficient power for the analyses that included all subjects, regardless of gender. An analysis of the primary outcome variables, with gender in the model, revealed no difference between men and women (Anton et al., 2006). Our analytic strategy for examining efficacy measures in this report was based on an a priori decision to perform the analyses in the parent report in parallel (i.e., separately) for men and women. It was recognized that the parallel gender analyses would be under-powered to some extent, so statistical results are reported at a trend level, with the understanding that some conclusions must be viewed as exploratory and tentative. The individual gender analyses for men and women, separately, were followed with an overall analysis of the entire experiment, identical to that of the parent report, except that we included gender and its interaction in all analyses. These overall analyses were used to confirm the analyses reported in the parent trial related to gender differences on the two primary outcome variables, as well as to help gauge confidence in the separate gender analyses performed on the additional outcome variables that were not analyzed previously for gender effects.

Comparisons of women and men on baseline characteristics and measures of treatment adherence for continuous variables were analyzed with analysis of variance and dichotomous variables with a chi-square.

RESULTS

Baseline Data

Demographics

Demographic information by gender (378 women, 848 men) for the baseline assessment instruments reported on in the parent study excluding Cell 9 participants is presented in Table 1. (The number of subjects in each category occasionally differs from the total of the whole sample of 1226, reflecting occasional missing data for that particular variable in the public database used in these analyses). The sample averaged 44 years of age, was predominantly of Caucasian ethnicity, married, employed with annual income greater than $30,000, and the average subject completed more than 12 years of education. There were no gender differences in any of these variables except for education, where women reported more years of education than men (p <.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Overall Sample as a Function of Gender

| Demographic Characteristics | Overall (n=1226) | Male (n=848) | Female (n=378) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 44.3 (10.2) | 44.1 (10.4) | 44.9 (9.7) |

| Race n (%) | |||

| White | 941 (76.8) | 642 (75.7) | 299 (79.1) |

| Hispanic | 138 (11.3) | 103 (12.1) | 35 (9.3) |

| African American | 100 (8.2) | 71 (8.4) | 29 (7.7) |

| Other | 47 (3.8) | 32 (3.8) | 15 (4.0) |

| Marital Status n (%) | |||

| Single | 337 (27.5) | 243 (28.7) | 94 (24.9) |

| Married | 516 (42.1) | 357 (42.1) | 159 (42.1) |

| Separated/Divorced | 308 (25.1) | 207 (24.4) | 101 (26.7) |

| Other | 65 (5.3) | 41 (4.8) | 24 (6.3) |

| Employment Status n (%) | |||

| Working/Homemaker | 897 (73.2) | 614 (72.4) | 283 (74.9) |

| Disabled/Unemployed | 193 (15.7) | 131 (15.4) | 62 (16.4) |

| Retired | 78 (6.4) | 57 (6.7) | 21 (5.6) |

| Other | 58 (4.7) | 46 (5.4) | 12 (3.2) |

| Income n (%) | |||

| Less than 15,000 | 120 (10.0) | 73 (8.8) | 47 (12.6) |

| 15–29.9 | 203 (16.8) | 151 (18.1) | 52 (13.9) |

| 30–59.9 | 359 (29.8) | 254 (30.5) | 105 (28.2) |

| 60–89.9 | 234 (19.4) | 160 (19.2) | 74 (19.8) |

| Over 90 | 290 (24.0) | 195 (23.4) | 95 (25.5) |

| Years of Education | |||

| Years Completed* | 14.6 (2.7) | 14.4 (2.7) | 15.1 (2.7)a |

| <=12 n (%) | 354 (29.4) | 275 (33.1) | 79 (21.3) |

| >12 n (%) | 849 (70.6) | 557 (66.9) | 292 (78.7) |

| Age at Onset of Alcohol Dependence* | 30.5 (11.31) | 29.6 (11.16) | 32.8 (11.38)a |

| Drinks/Drinking Day* | 12.5 (7.97) | 13.9 (8.33) | 9.6 (6.12)b |

| % Days Drinking* | 74.7 (25.03) | 74.8 (25.27) | 74.6 (24.51) |

| % Heavy Drinking Days* | 65.6 (28.49) | 66.2 (28.73) | 64.2 (27.92) |

| Alcohol Dependence Score* | 16.7 (7.36) | 16.7 (7.53) | 16.7 (6.98) |

| AUDIT-Total Score* | 25.8 (6.11) | 26.0 (6.10) | 25.5 (6.11) |

Mean (SD)

Females > Males, p<.001

Females < Males, p<.001

Baseline drinking measures

Table 1 also shows the baseline data on drinking measures as a function of gender. As expected from the published literature, women had a later age of onset of alcohol dependence and drank significantly fewer alcoholic drinks than men on days that they drank. There were no gender difference in percent heavy drinking days (defined as 4 or more drinks for women and 5 or more drinks for men), percent any drinking days, Alcohol Dependence Scale scores or AUDIT total scores. Thus, aside from expected gender differences in age of onset and daily drinking quantity, baseline alcohol measures revealed little difference between men and women on drinking severity. An additional point worth noting, the COMBINE study represented the first alcohol treatment experience for many women. Only 41.2% of women had a history of prior alcohol treatment as compared to 52.9% of men (p<.001).

Drop out, completeness of data, and treatment adherence

There were no gender differences in study drop out (p=.73), incomplete drinking data (p= .753), missing CBI therapy sessions (p=.91), or stopping or missing MM sessions (p>.5). Drinking data were complete for 93.9% of the females and 93.3% of the males (p=.68). There was a trend for more men than women who received CBI to stop attending CBI sessions prematurely (24.6% vs 19.6%; p=.126). Medication adherence,. assessed as percentage of pills taken versus returned, did not differ between male and female subjects (p=.70).

Drinking Outcomes as a Function of Gender

Primary Dependent Variables

Percent Days Abstinent

Percent days abstinent, expressed as four, 4-week accumulations from the 16-week trial, was analyzed as a mixed model (SAS PROC MIXED) with an unstructured variance/covariance matrix. Clinical Center was used as a covariate, as was baseline percent days abstinent. These covariates did not interact with the main treatment variables.

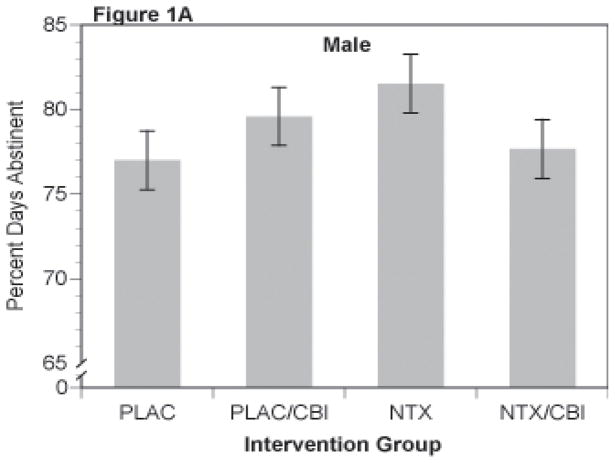

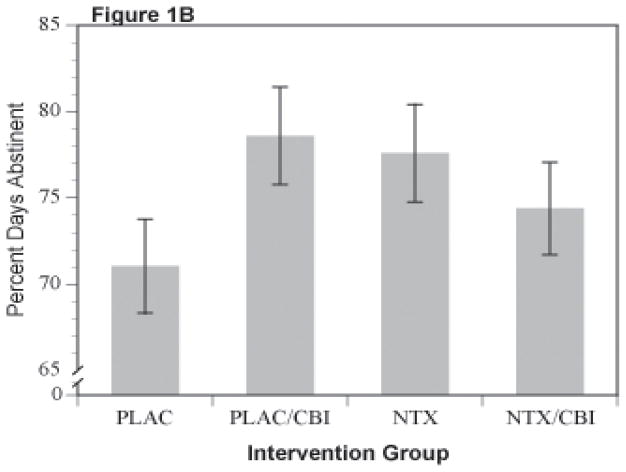

Results for percent days abstinent yielded the same overall pattern in each gender as that observed in the original report. That is, of the major comparisons, only the naltrexone (NTX) by CBI interaction reached or approached significance, f(1,824)=3.86, p=.05 and f(1,360)=3.52, p=.061 for women and men respectively. There were no other main effects or interactions, particularly no evidence of acamprosate action or interaction of acamprosate with either CBI or NTX. Least-square cell means are shown for the NTX by CBI interaction in the two genders in Figures 1A (men) and 1B (women). In men, the difference between the naltrexone alone (labeled NTX in Figure 1A) and the placebo alone groups (labeled PLAC in Figure 1A) approached significance, p=.06). In women (Figure 1B), there were trends for both the naltrexone alone (i.e., NTX) and CBI alone (i.e., PLAC/CBI) groups to be superior to the placebo alone (i.e, PLAC) group p=.092 and .052, respectively (nominal, uncorrected p-values). There were no other significant contrasts between the other treatment groups. The combined treatment (labeled as NTX/CBI in Figures 1A and 1B) was intermediate in effect in both men and women, indicating that the combination was not different from placebo or from the single treatment groups (p >.25).

Figure 1.

Percent Days Abstinent for Combinations of Naltrexone and CBI in Male (Figure 1A) and Female (Figure 1B) Subjects

The overall analysis, which included both men and women, supported these observations done separately for men/women reported above. That is, only the main effect of gender (p=.027) and the naltrexone by CBI interaction (p=.008) were significant in the full factorial model (naltrexone x acamprosate x CBI x gender). Females had significantly lower percent days abstinent values than did male subjects within the 16-week treatment period (women=75.4 ± 1.33, men =79.0 ± .88,; p=.027), while the interaction was similar to that observed within the men and women subjects separately. These results support the overall lack of gender differences reported in the trial’s primary outcome paper (Anton et al, 2006)

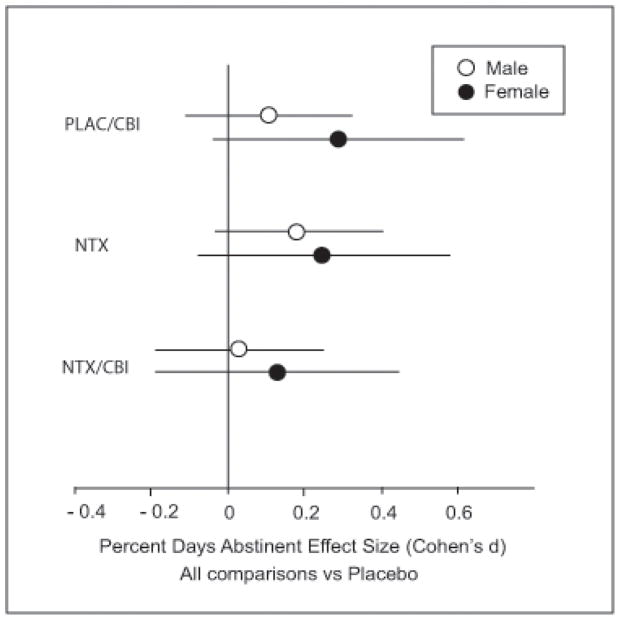

This pattern, in which one or both single treatments (i.e., NTX or CBI) is superior to placebo, but in which the combined treatment of NTX and CBI is less than additive is consistent across all of the outcome measures, with only minor exceptions, as follows. While it is clear that the combined response is less than additive, it is unclear whether combined treatment is actually inferior to the individual treatment modalities given singly, since the effect differs depending upon the outcome variable. The similarity of the pattern in male and female subjects is further reinforced by examination of effect sizes for contrasts contributing to the NTX by CBI interaction. Figure 2 shows Cohen’s d and the 97.5% confidence interval for men and women with CBI alone (PLAC/CBI), Naltrexone alone (NTX), or the combination of Naltrexone and CBI (NTX/CBI).

Figure 2.

Percent Days Abstinent Effect Sizes (Cohen’s d) for Combinations of Naltrexone and CBI vs Placebo in Male and Female Subjects

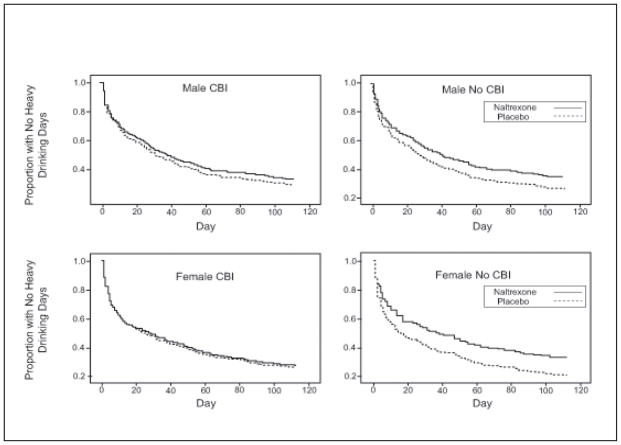

Time-to-First-Heavy-Drinking-Day

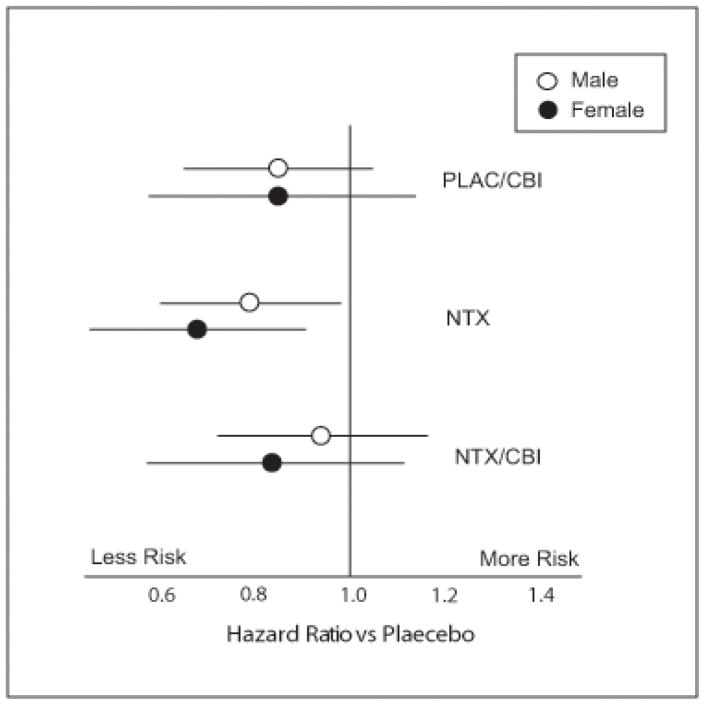

Time to first heavy drinking day was analyzed in a Cox proportional hazards model (SAS PROC PHREG) similar to that employed in the parent-trial report (Anton et al., 2006). Results were similar to those of the parent report on the entire sample (Anton et al., 2006). In men, the NTX by CBI interaction was significant (p=.048) with CBI and NTX both independently producing slower relapse to first heavy drinking day, but the combination showing no further benefit. A similar result was obtained in women, but the interaction approached, but did not reach, significance (p=.12). These data are plotted as survival curves for both men and women in Figure 3. The effect size (hazard ratio) for the NTX x CBI interaction is shown in Figure 4. The overall model with gender and its interaction included supported these observations. The NTX x CBI interaction was highly significant (p=.019) and the pattern of results did not vary with gender (naltrexone x CBI x gender, p=.90).

Figure 3.

Survival Curves for Time to First Heavy Drinking Day by Naltrexone and CBI Combinations in Male and Female Subjects. Curves represent best fitting Cog Regression model

Figure 4.

Return to Heavy Drinking Ratios for Males and Females Receiving Different Combinations of Naltrexone and CBI vs Placebo

SECONDARY DEPENDENT VARIABLES

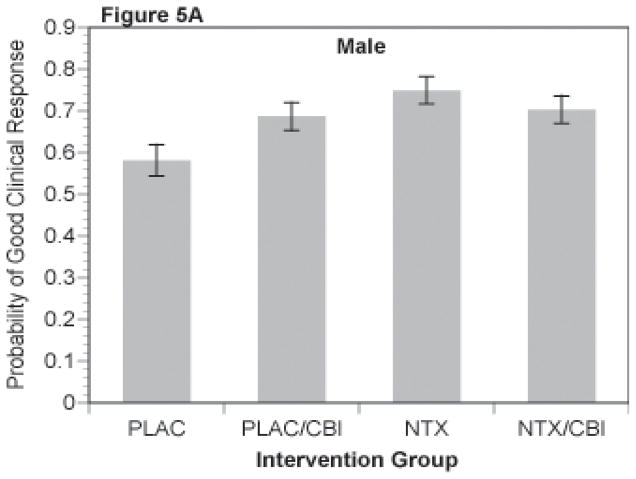

Good Clinical Response

A binary variable coding a favorable clinical response defined in the parent trial as abstinence or moderate drinking without problems (Anton et al., 2006) was analyzed via logistic regression analyses (SAS PROC LOGISTIC). The least square means for estimated probability of a good clinical response for the NTX by CBI cells for men is shown in Figure 5A and for women in Figure 5B. The NTX by CBI interaction was significant in the separate analysis of men (p=.043). For women, this interaction only approached statistical significance (p=.12), but demonstrated a similar pattern of results. As shown in the figures, CBI alone was greater than placebo (p <.03) and naltrexone alone was greater than placebo (p = .01) for both men and women.

Figure 5.

Figure 5A and 5B. Probability of Good Clinical Response for Combinations of Naltrexone and CBI

Similar to the two primary dependent variables described above, the binary “good clinical outcome” composite showed a strong NTX by CBI interaction in the overall analysis that included gender in the model (p = .011). Again, there were no other main effects or interactions.

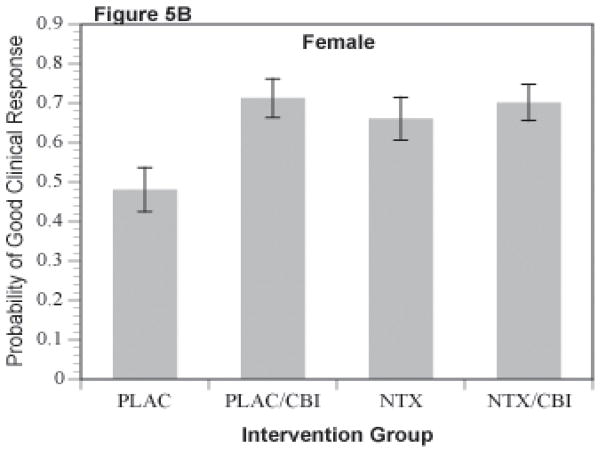

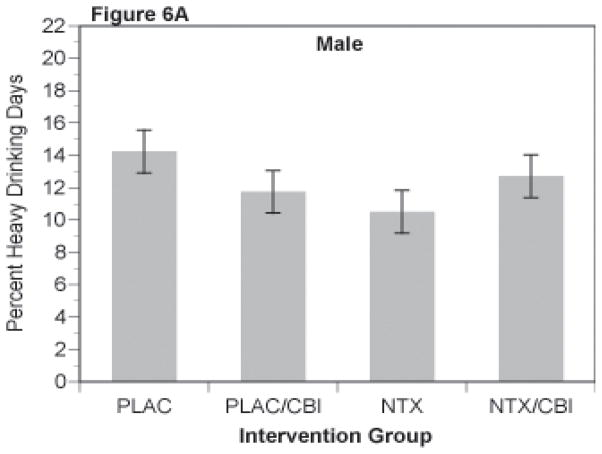

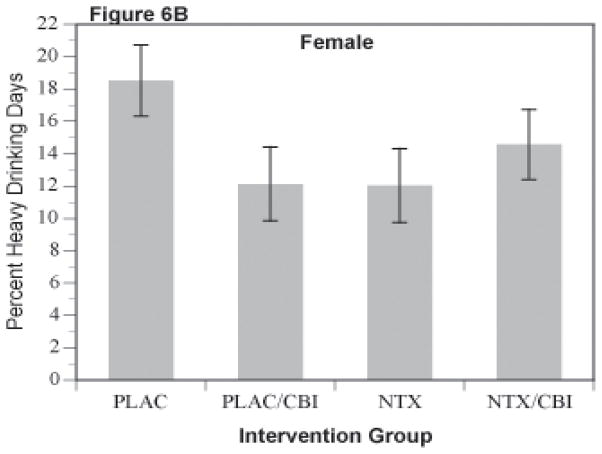

Percent heavy drinking days

Percent heavy drinking days, like percent days abstinent, was analyzed as a repeated measures mixed model with 4 repeated observations, each representing an accumulation across 4 weeks of the 16 week trial. As shown in Figures 6A and 6B, this secondary outcome repeated the pattern observed with the other outcomes, i.e. NTX or CBI alone was superior to the groups receiving neither (i.e., PLAC group). Those receiving the combination of NTX and CBI were intermediate in response. These observations were supported by the mixed model analysis with the NTX by CBI interaction being significant in the overall analysis [f(1,1194)=8.63]. In the separate analyses, the interaction was significant in women [f(1,360)=4.08, p=.0034], and approached significance in men [f(1,824)=3.17, p=.075].

Figure 6.

Percent Heavy Drinking Days for Combinations of Naltrexone and CBI in Male (Figure 6A) and Female (Figure 6B) Subjects

Craving

In both men and women, the NTX main effect on the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) scale (Anton et al, 1996) was significant with naltrexone-treated subjects reporting lower craving than PLAC- treated subjects: f(1,816)=6.49, p=.011 and f(1,355)=4.64, p=.032 for men (mean 11.7, s.d.7.8 vs mean 13.1, s.d.7.98) and women (mean 12.8, sd7.9 vs. mean 14.0, sd7.4) respectively. Effect sizes were similar for the two genders: d=0.22 and 0.18 for males and females respectively.

DISCUSSION

The participant numbers in the NIAAA multi-site COMBINE Study (N=1383) offered a unique opportunity to examine the study’s main results for women separately from men. For the present analyses, we performed a focused examination of selected measures obtained from the majority of the COMBINE study’s women (i.e., n=378 women who received study medication out of a total of 428 women in the trial). Men are typically overepresented in alcohol-dependent clinical trials, and so most available treatment study samples are much smaller and usually do not permit a fair analysis of whether women respond to the investigated treatment. In addition, the present analyses generate information on gender differences in response to medications, like naltrexone, that treat alcohol dependence -- a relatively unexplored area, similar to gender response in alcohol-dependent patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Pettinati, Dundon & Lipkin, 2004).

The present study confirmed the primary findings from the original COMBINE Study, i.e., a significant naltrexone by CBI interaction, for women, separately from men, on two primary outcomes (percent days abstinent; time to first heavy drinking day), and three secondary outcome measures (good clinical response, percent heavy drinking days, and craving for alcohol). Essentially, alcohol-dependent women, like alcohol-dependent men, who received medical management plus naltrexone (no CBI specialty therapy), or, medical management and CBI (no naltrexone), had a better treatment response than those taking placebo or any of the other individual or combination treatments that were investigated in the COMBINE study. For example, we found in the present analyses that acamprosate was no more effective than placebo in women, as well as in men – similar to the results for the overall sample in the parent trial. Treatment effects, while modest, were as large (on some measures larger) in women compared to men. The size of the female subsample in the present study provides confidence that alcohol-dependent women are treatment responders to naltrexone or CBI, in the context of medical management, and there are no detectable treatment-response differences between women and men. The finding also suggests that prior studies of naltrexone in women may have been negative due to inadequate sample sizes

In-trial alcohol craving and changes were also comparable between men and women – only naltrexone affected craving (similar to the parent trial results). However, in the overall analysis of in-trial abstinence, there was a main effect of gender where women, compared to men, reported fewer days of in-trial abstinence, or more days of drinking. This finding is most obvious when comparing the women and men not taking active medication (i.e., receiving placebo tablets), and least obvious when comparing the women and men in specialty therapy (CBI). Because abstinence is the only outcome measure where we found that women responded more poorly than men, this result requires replication, and it would be interesting to investigate this further in future studies. Furthermore, the combined condition, CBI plus naltrexone, had intermediate effect depending on outcome considered for reasons that are not understood at this time. Future studies might consider examining whether outcomes vary as a function of gender and treatment condition depending on whether the endpoint measured is abstinence, reduction in heavy drinking days, or some measure of good clinical response.

In addition to demonstrating that in the COMBINE study, women responded to alcohol treatment like the men, we found evidence of many similarities between these women versus men on pre-treatment as well as in-trial measures. In general, women and men had comparable demographics, pretreatment clinical characteristics, and rates of retention and medication adherence. With regard to the few significant differences between men and women, women had more years of education than men, generally considered a good prognostic indicator (Greenfield et al., 2003). In addition, women reported a later age of onset of alcohol dependence by an average of approximately 3 years than men, and they reported drinking significantly fewer drinks per drinking day than did men consistent with previous literature on this topic [Randall et al, 1999]. In spite of alcohol severity similar to men, women in this study were less likely to have received alcohol treatment in the past. Studies of community samples have shown that women are less likely than men to receive any treatment for their alcohol problems over their lifetime (Dawson, 1996). Some previous studies with clinical samples have indicated that fewer women with alcohol dependence entered treatment than men (Schober & Annis, 1996; Weisner, Greenfield, & Room, 1995), while a more recent study indicated similar rates of treatment entry for both men and women (Weisner, Mertens, Tam, & Moore, 2001). Barriers to obtaining treatment for alcohol dependence for women remain and are well documented (Greenfield et al., 2007). In the COMBINE study sample, more women than men were obtaining their first alcohol treatment through participation in a clinical research study. It is unclear if this may be due to women’s perceiving lower stigma for entering a research trial for treatment of alcohol dependence, or experiencing fewer barriers (e.g., cost of treatment, inadequate or lack of insurance, among others) to entering the RCT than other clinical treatment options. Once enrolled, women had comparable levels of attendance in MM and medication adherence and somewhat higher rates of completing CBI compared to men.

The present study has several limitations, in addition to those reported by Anton et al, 2003. Most notably, individuals taking antidepressants, anxiolytics and other psychotropic medications were excluded from the COMBINE parent trial; and women, compared to men, are more likely to be taking these medications because of co-occurring depression, anxiety, etc. (Grant et al, 2004). It is debatable whether the finding of many similarities between women and men on pre-treatment and in-trial measures, including outcome results, might have been different if we had included individuals with co-occurring illnesses or those who were also taking psychotropic medications. The literature has been inconsistent with regard to whether co-occurring psychiatric disorders are associated with poorer, better, or even similar treatment outcomes compared to alcohol-dependent individuals without co-occurring disorders (see review by Pettinati & Plebani, 2009). Thus, it is difficult to infer whether women with co-occurring anxiety or depressive disorders and alcohol dependence would have had a differential response to naltrexone or CBI from alcohol dependent men with or without these disorders. Individuals with co-occurring drug dependence were also excluded from the COMBINE trial. In this case, poorer outcomes have been consistently associated with co-occurring drug dependence and abuse (Heil et al., 2001; Pettinati et al., 2008). Another limitation is that clinical trials tend to include very traditional pre-treatment and outcome measures, which might not be gender sensitive, leading to finding no gender differences (e.g., no measures were included of childrearing responsibilities). Finally, our analysis focused on the 16 week- treatment period. It is conceivable that gender differences might emerge later given that response to cognitive behavioral treatment may sometimes occur at a time more distal to treatment, the so-called sleeper effect (Carroll, 1994).

In summary, the purpose of the present study was to focus on the treatment implications of the large, multicenter NIAAA-sponsored COMBINE Study results for women with alcohol dependence, given that this study provides a large subgroup of alcohol-dependent women where results are more likely to be replicable. This gender-focused analysis found that, despite modest effect sizes, the findings from the original COMBINE study were supported for women as well as for men. In particular, the alcohol-dependent women responded to naltrexone with medical management, similar to the alcohol-dependent men, on a wide range of outcome measures. These results suggest that clinicians can feel reasonably comfortable prescribing naltrexone for alcohol dependence in both men and women. Also, as discovered in the parent trial, the effects of naltrexone were most apparent in the context of a medical model of counseling that can be delivered in primary health care settings (COMBINE’s Medical Management). In this study, it is also notable that fewer women than men reported receiving any alcohol treatment prior to entry into the COMBINE study. Of note, women tend to go to primary health care more frequently than to specialty substance abuse programs for treatment (Weisner & Schmidt, 1992), and so the benefit we confirm for women of the naltrexone and medical management combination has practical implications for treating alcohol-dependent women.

Acknowledgments

The reported data were collected as part of the multisite COMBINE Study sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Further information about study sites, staff and other publications from the COMBINE Study can be found at http://www.cscc.unc.edu/COMBINE. The authors would like to acknowledge Grants U10 AA011783 (CLR) and P50 AA010761 (PKR); U10 AA 11756 (SFG) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; and Grant K24DA019855 (SFG) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The medications for the COMBINE Study were donated by Lipha Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosures: Dr. O’Malley is a member of the ACNP Alcohol Clinical Trial Initiative, sponsored by Eli Lilly, Janssen, Schering Plough, Lundbeck, Glaxo-Smith Kline and Alkermes; partner in Applied Behavioral Health; member Scientific Panel Butler Center for Research at Hazelden; and has participated in studies in which NABI Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi-Aventis donated medications and received travel reimbursement for talks at the Controlled Release Society, the Drug Information Association, and the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse.

References

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PK. The Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. A new method of assessing outcome in alcoholism treatment studies. Arch Gen Psychiat. 53:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030047008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley Ss, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence: The COMBINE Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baros AM, Latham PK, Anton RF. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of alcohol dependence: do sex differences exist? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008 May;32(5):771–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00633.x. Epub 2008 Mar 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin F. One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The COMBINE Study Research Group. Testing combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions in alcohol dependence: Rationale and methods. Alcoholism Clinical Experimental Research. 2003;27:1107–1122. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CA, Polen MR, Dickinson DM, Lynch F, Bennett MD. Gender differences in pedictors of initiation, retention and completion in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. J Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Sugarman DE, Muenz LR, Patterson MD, He DY, Weiss RD. The relationship between educational attainment and relapse among alcohol-dependent men and women: A prospective study. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1278–1285. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080669.20979.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Bucholz KK, Rice JP, Bierut LJ. Secular trends in the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence in the United States: A re-evaluation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Resarch. 2008;32:763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva R, Wu R, Pittman B, Cramer J, Rosenheck RA, O’Malley SS, Krystal JH. New insights into the efficacy of naltrexone based on trajectory-based reanalysis of two negative clinical trials. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:1290–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. Alcohol dependence among cocaine-dependent outpatients: Demographics, drug use, treatment outcome and other characteristics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(1):14–22. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Wing S, McCarty D, et al. Self-help organizations for alcohol and drug problems: Toward evidence-based practice and policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:151–158. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden R, Carroll K, Donovan D, et al. DHHS. Cognitive-Behavioral Coping Skills Therapy Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating Individuals with Alcohol Abuse and Dependence. Vol. 3. Government Printing Office; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcoholl use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer Falk, Jahn H, Wiedemann K. A Neuroendocrinological Hypothesis on Gender Effects of Naltrexone in Relapse Prevention Treatment: Letter to the Editor. Preview Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005 Jul;38(4):184–186. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871244. [Letter] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC, Jamner LD, Alberts J, Ornstein MD, Leigh H. Sex differences in salivary cortisol levels following naltrexone administration. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2000;5:144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. DHHS. COMBINE Monograph Series. Vol. 1. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series; 2004. Combined Behavioral Intervention Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating People with Alcohol Abuse and Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Smith JE. Clinical Guide to Alcohol Treatment: The Community Reinforcement Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Sinha R, Grilo CM, Capone C, Farren CK, McKee SA, Rounsaville BJ, Wu R. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral coping skills therapy for the treatment of alcohol drinking and eating disorder features in alcohol dependent women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Dundon WD, Lipkin C. Gender differences in response to sertraline pharmacotherapy in type A alcohol dependence. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:236–247. doi: 10.1080/10550490490459906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Plebani JG. Depression and substance use disorders in women. In: Brady K, et al., editors. Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati Helen M, Kampman Kyle M, Lynch Kevin G, Suh Jesse J, Dackis Charles A, Oslin David W, O’Brien Charles P. Gender differences with high-dose naltrexone in patients with co-occurring cocaine and alcohol dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008 Jun;34(4):378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati H, Weiss R, Miller W, Donovan D, et al. DHHS. Vol. 2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2004. Medical Management (MM) Treatment Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Medically Trained Clinicians Providing Pharmacotherapy as Part of the Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. COMBINE Monograph Series. [Google Scholar]

- Suh JJ, Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, O’Brien CP. Gender differences in predictors of treatment attrition with high dose naltrexone in cocaine and alcohol dependence. Am J Addict. 2008 Nov–Dec;17(6):463–8. doi: 10.1080/10550490802409074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Kathleen M, Kviz Frederick J, Isola Miriam L, Filstead William J. Evaluating multiple outcomes and gender differences in alcoholism treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1995 Jan–Feb;20(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Gavric D, Collins P. Women, Girls, and Alcohol. In: Brady K, Back S, Greenfield SF, editors. Women and Addiction: A Comprehensive Handbook. Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline rollowback: a technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Schmidt L. Gender disparities in treatment for alcohol problems. JAMA. 1992;268(14):1872–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]