Abstract

The intrinsically unfolded protein α-synuclein has an N-terminal domain with seven imperfect KTKEGV sequence repeats and a C-terminal domain with a large proportion of acidic residues. We characterized pKa values for all 26 sites in the protein that ionize below pH 7 using 2D 1H-15N HSQC and 3D C(CO)NH NMR experiments. The N-terminal domain shows systematically lowered pKa values, suggesting weak electrostatic interactions between acidic and basic residues in the KTKEGV repeats. By contrast, the C-terminal domain shows elevated pKa values due to electrostatic repulsion between like charges. The effects are smaller but persist at physiological salt concentrations. For α-synuclein in the membrane-like environment of sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) micelles, we characterized the pKa of His50, a residue of particular interest since it is flanked within one turn of the α-helix structure by the Parkinson's disease-linked mutants E46K and A53T. The pKa of His50 is raised by 1.4 pH units in the micelle-bound state. Titrations of His50 in the micelle-bound states of the E46K and A53T mutants show that the pKa shift is primarily due to interactions between the histidine and the sulfate groups of SDS, with electrostatic interactions between His50 and Glu46 playing a much smaller role. Our results indicate that the pKa values of uncomplexed α-synuclein differ significantly from random coil model peptides even though the protein is intrinsically unfolded. Due to the long-range nature of electrostatic interactions, charged residues in the α-synuclein sequence may help nucleate the folding of the protein into an α-helical structure and confer protection from misfolding.

Keywords: ionization constant, fibrillogenesis, denatured state, membrane proteins, amyloid, protein folding, synucleinopathies

Introduction

Alpha-synuclein (αS) is a 14.5 kDa protein expressed predominantly at the presynaptic terminals of brain neurons.1,2 The physiological function of the protein remains unknown1 although a role in synaptic vesicle recycling has been suggested.3,4 Misfolding of αS leads to the formation of fibrillar cytoplasmic aggregates5,6 called Lewy bodies, which are a defining characteristic of Parkinson's disease.7–10 Because the number of Lewy bodies is often poorly correlated with the severity of symptoms, controversy surrounds the issue of whether fibrils or smaller soluble oligomers are responsible for the neurotoxicity of misfolded αS.11 Regardless of the mechanism of neurotoxicity, genetic evidence establishes a link between the αS gene and Parkinson's disease. Although 90–95% cases of Parkinson's disease cases are sporadic,12 the autosomal-dominant familial mutations A30P, E46K, A53T, as well as the triplication of the wild-type αS gene lead to early onset of the disease.1,7,13,14

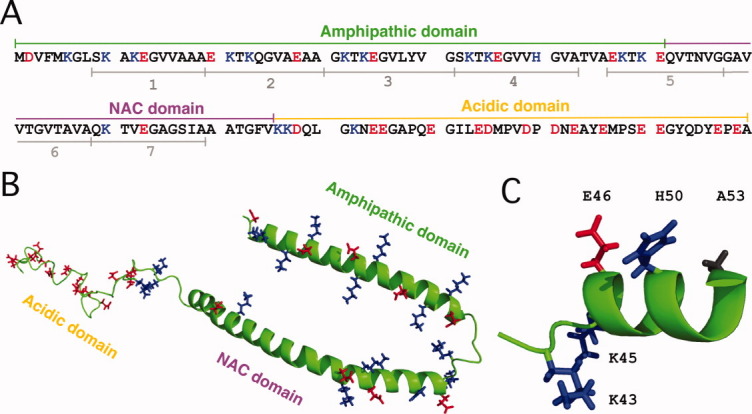

The amino acid sequence of αS can be subdivided into three domains with unusual distributions of charged residues [Fig. 1(A)]. The first 90 residues of αS contain seven imperfect repeats of the amino acid sequence xKTKEGVxxxx,15 which are important for the induction of α-helical structure in αS17 and for binding to membranes containing negatively charged lipids that the protein prefers.16–18 Residues 61-95 of αS correspond to the hydrophobic “non-amyloid-β component” (NAC), the most aggregation-prone part of the protein.19–24 The name NAC, derives from the occurrence of this segment as a second protein component of the extracellular amyloid-β plaques found in patients with Alzheimer's disease.25 The mechanism by which the NAC fragment of the intracellular αS is cleaved and comes to be associated with extracellular amyloid-β plaques is unknown. The last two KTKEGV repeats are in the NAC segment,15 however, due to their imperfect nature only two charged residues Lys80 and Glu83 occur in the hydrophobic region between residues 62 and 95. The last 40 amino acids of αS contain 15 acidic residues, giving the C-terminal tail of the protein a negatively charged character at physiological pH.

Figure. 1.

Sequence of αS and structure of the protein bound to SDS micelles. (A) The three domains of the αS amino acid sequence and the locations of the seven xKTKEGVxxxx repeats.15 (B) Structure of αS bound to SDS micelles (PDB code: 1XQ8),16 showing the side-chains of residues that are positively (blue) or negatively charged (red) at neutral pH. (C) Expanded view of the micelle-bound αS structure showing the location of His50 in relation to Glu46 and Ala53 (the sites of the familial Parkinson's mutations E46K and A53T). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Monomeric αS is intrinsically unfolded with a fractional population of at most 10–20% α-helix structure.22,26 The first ∼90 residues of the protein fold into an α-helical structure in the membrane-like environments provided by micelles, vesicles, or bilayers that contain a large fraction of negatively charged lipids.21,27–30 By contrast, the negatively charged C-terminal tail remains disordered when αS binds to lipid assemblies.16,27,28,31 The highest-resolution structure available for αS in a membrane environment is for the protein bound to sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) micelles.16 SDS forms relatively small micelles that are amenable to direct high-resolution NMR studies.16,31 When bound to SDS micelles, the amphipathic N-terminal domain of αS forms two long α-helices that lie on the surface of the micelle. Under other conditions the protein folds into an uninterrupted α-helix.29,32,33 The interconversion between a broken and uninterrupted α-helix has been shown to have a subtle dependence on micelle or vesicle size,29,32 the ratio of protein to micelles,33 as well as the aggregation state of the protein.34 The structure of αS bound to SDS micelles16 is shown in Figure 1(B). The view of the structure is opposite to the face of the protein that interacts with the micelles. Charged residues are shown in blue (positive) and red (negative). It is important to note that the structure of αS bound to SDS micelles was determined with perdeuterated protein samples using NMR experiments that look at the protein backbone.16 As such, there is no information on the conformations of side-chains in the αS structure; these are shown in random orientations in Figure 1(B,C). In an α-helix, residues separated by three or four positions in the sequence have the potential to form ion-pairs.35 Consideration of the αS sequence and α-helix structure suggests that residues in the amphipathic domain of the protein are poised to form electrostatic interactions between the acidic and basic amino acids pairs Asp2-Lys6, Lys10-Glu13, Glu20-Lys23, Glu28-Lys32, Lys32-Glu35, Lys42-Glu46, Glu46-His50, Glu57-Lys60, Lys58-Glu61, and Lys80-Glu83. By contrast, the negatively charged residues in the C-terminal tail should be subject to electrostatic repulsion due to a high density of like charges.

Because charges could be important in the folding and misfolding of α-synuclein, we determined pKa values for all sites in the protein that ionize below pH 7. A number of studies have shown that pKa values of unfolded proteins deviate from random coil model compounds.36–40 The unusual distribution of charged residues in αS provides a stringent test of the assumption that pKa values of residues in unfolded proteins approximate those of random coils. The unfolded state is an important reference state for the theoretical analysis of the roles of charges in protein structure stabilization.37,40,41 Accurate pKa values for unfolded αS will help model the effects of charges on the structures of membrane-bound and fibrillar αS. In addition to extensive studies on the free protein, we obtained pH titration data for His50 in αS bound to SDS micelles. His50 is a residue of particular interest because it is part of a high-affinity binding-site for Cu2+, a metal which has been implicated in Parkinson's disease and that markedly increases the fibrillization rates of αS.42 Moreover, in the αS structure, His50 is within one turn of α-helix of the sites of the two familial Parkinson's disease mutations E46K and A53T [Fig. 1(C)] that could perturb the electrostatic environment of His50.

Results

pKa values for αS in the absence of salt

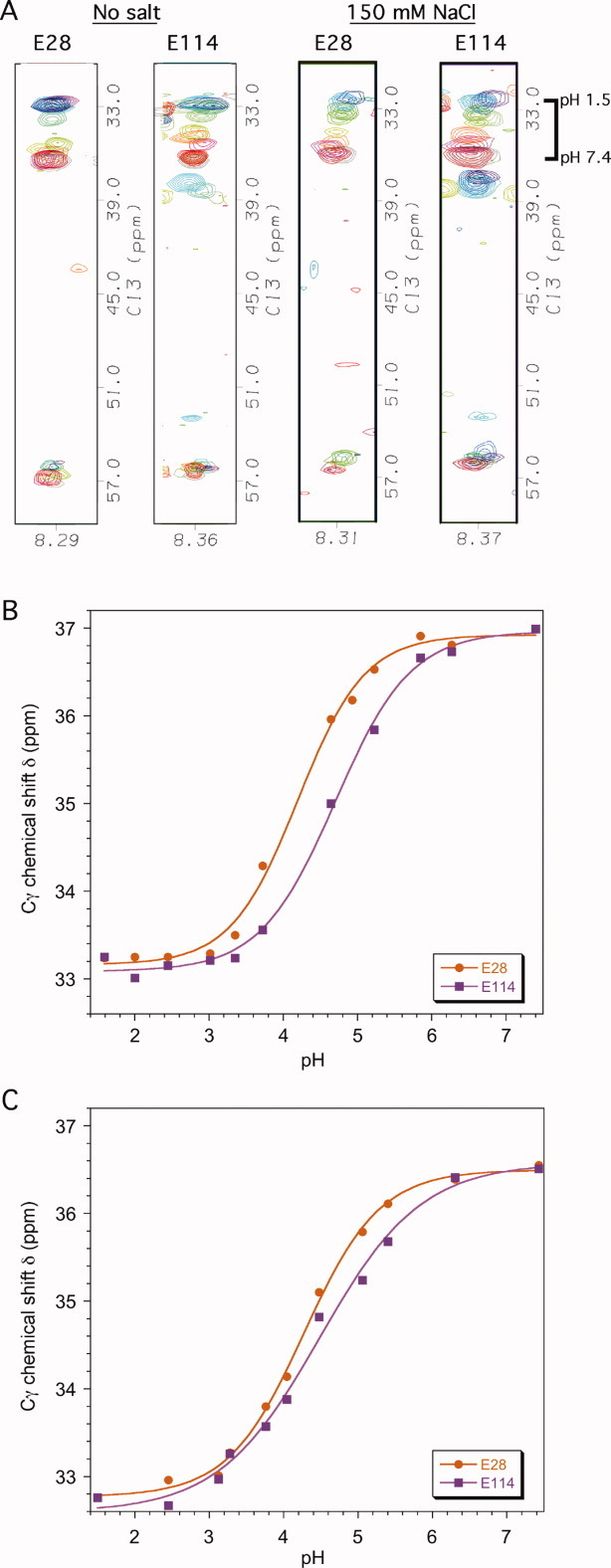

Ionization constants for aspartate and glutamate residues in αS were obtained from 3D C(CO)NH experiments recorded at different pH values. The links the amide of a given residue with all the aliphatic 13C resonances of the preceding residue. By correlating spin systems with the well dispersed nitrogen of the following amino acid in the sequence, the C(CO)NH experiment43 circumvents the spectral overlap typically encountered for Asp and Glu side-chains, which is particularly severe for unfolded proteins like αS. For αS we found that the intensity of Asp Cβ correlations were stronger than those of Asp Cα, the Glu Cγ correlations were stronger than Glu Cα, while Glu Cβ crosspeaks were usually not observed.44 Fortuitously, the strongest crosspeaks were from the aliphatic carbons closest to the titrating carboxyl groups of the acidic residues. Representative data for Glu28 and Glu114 showing superimpositions of 2D slices from the 3D C(CO)NH experiments obtained at pH values between 7.4 and 1.5 are shown in Figure 2(A). The pH dependence of the Cγ chemical shifts of Glu28 and Glu114 in the absence of salt is shown in Figure 2(B). The glutamate Cγ carbons shift from ∼37 ppm at neutral pH, to ∼33 ppm at acidic pH. For the aspartate Cβ carbons the corresponding shift is between ∼42 and ∼38 ppm. The Cα resonances are also sensitive to the titration of the carboxyl groups but the pH dependence of these shifts is much smaller, typically from ∼57.0 to ∼56.0 ppm for glutamate and ∼54.5 to ∼53.0 ppm for aspartate between neutral and acidic pH.

Figure. 2.

Representative pH titration data. (A) Superposed 2D strips from 3D C(CO)NH experiments used to determine pKa values for Glu and Asp residues in the absence and presence of 150 mM NaCl. Contours are shown for residues Glu28 and Glu114 on a red (neutral) to blue (acidic) color ramp between pH 7.4 and pH 1.5. The individual pH values are shown in panels B and C. The width of the strips in the HN dimension is 0.1 ppm. The contours centered at ∼38 ppm in the strips for Glu114 are from another spin system that appears in the same HN and N frequency range at low pH. (B) pH titration data for Glu28 and Glu114 in the absence of salt. (C) pH titration data for Glu28 and Glu114 in the presence of 150 mM NaCl. The curves are nonlinear least squares fits of the data to Eq. 1 that were used to obtain the titration parameters in Table I. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The 3D C(CO)NH experiment enabled us to obtain data for 21 of the 26 sites that ionize between neutral and acidic pH in αS. The sites that could not be characterized were His50, Glu61, Asp119, Glu137, and the α-carboxyl group at the C-terminus. The 3D C(CO)NH experiment was not applicable for the residue pairs D119-P120 and E137-P138 because proline lacks an amide proton with which to correlate the preceding spin system. Similarly, the α-carboxyl group is at the end of the sequence (Ala140), and the titration of the His50 cannot be detected in the C(CO)NH experiment due to its aromatic side-chain. For these sites pKa values were obtained by monitoring the pH dependence of 1H-15N correlations in 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra. In the case of Glu61, the E61(Cγ)-Q62(HN) spin system occurs as a partially overlapped shoulder on the E114(Cγ)-D115(HN) spin system throughout most of the pH transition. While we could obtain accurate data for the Cγ resonance of Glu114 from the C(CO)NH experiments, the titration of Glu61 was more accurately determined from the 15N resonance in 2D 1H-15N HSQC experiments. Consistent with previous results on unfolded proteins,45 we found that the 15N shifts of ionizable residues in αS are dominated by the protonation of the residue's own side-chain.

The sequence of αS has seven instances of Glu-Gly pairs [Fig. 1(A)]. The E83(Cγ)-G84(HN) and E131(Cγ)-G132(HN) spin systems were well resolved so that unambiguous pKa values were obtained for Glu83 and Glu131 from the 3D C(CO)NH experiments. The two correlations E35(Cγ)-G36(HN) and E110(Cγ)-G111(HN) overlap between pH 7.4 and 4.0 but separate at lower pH. We based our assignments on a slightly more downfield 15N chemical shift of 110.9 for Gly111 compared to 110.5 for Gly36.22 The assignments are tentative, however, as indicated in Table I. The three correlations E13(Cγ)-G14(HN), E46(Cγ)-G47(HN), and E105(Cγ)-G106(HN) were unresolved throughout the entire pH range in the absence of salt. We assigned a single pKa value obtained from the pH titration of the unresolved correlation to all three residues Glu13, Glu46, and Glu105 but estimate that the individual values differ by at most 0.1 pH unit from the unresolved pKa of 4.21.

Table I.

pKa Values of αS in the Absence and Presence of Salta

| No salt | 150 mM NaCl | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | pKa | n | δlow | δhigh | pKa | n | δlow | δhigh | Resonance |

| Asp2 | 3.61 ± 0.05 | 1.30 ± 0.21 | 38.64 ± 0.09 | 41.99 ± 0.06 | 3.63 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 122.81 ± 0.05 | 124.92 ± 0.03 | Cβ/Nb |

| Glu13c | 4.21 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 33.11 ± 0.08 | 36.79 ± 0.08 | 4.32 ± 0.09 | 1.42 ± 0.35 | 32.85 ± 0.14 | 36.24 ± 0.16 | Cγ |

| Glu20 | 4.07 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 33.10 ± 0.05 | 36.74 ± 0.04 | 4.24 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 32.77 ± 0.19 | 36.49 ± 0.18 | Cγ |

| Glu28 | 4.20 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 33.16 ± 0.08 | 36.92 ± 0.08 | 4.27 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 32.77 ± 0.06 | 36.50 ± 0.06 | Cγ |

| Glu35d | 4.17±0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 33.11 ± 0.07 | 36.69 ± 0.07 | 4.08 ± 0.13 | 0.88 ± 0.20 | 30.42 ± 0.41 | 36.39 ± 0.29 | Cγ |

| Glu46c | 4.21±0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 33.11 ± 0.08 | 36.79 ± 0.08 | 4.31 ± 0.10 | 0.86 ± 0.15 | 32.99 ± 0.18 | 36.39 ± 0.13 | Cγ |

| His50 | 6.78 ± 0.04 | 1.08 ± 0.08 | 123.11 ± 0.02 | 125.05 ± 0.06 | 6.52 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.37 | 123.45 ± 0.02 | 125.05 ± 0.05 | N |

| Glu57 | 4.20 ± 0.05 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 33.10 ± 0.07 | 36.87 ± 0.07 | 4.33 ± 0.09 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 32.89 ± 0.13 | 36.49 ± 0.13 | Cγ |

| Glu61 | 4.04 ± 0.27 | 0.86 ± 0.35 | 121.05 ± 0.07 | 121.70 ± 0.08 | 3.97 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.22 | 121.35 ± 0.04 | 122.07 ± 0.02 | N |

| Glu83 | 4.35 ± 0.05 | 1.07 ± 0.10 | 33.14 ± 0.06 | 36.71 ± 0.07 | 4.33 ± 0.03 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 32.70 ± 0.05 | 36.32 ± 0.05 | Cγ |

| Asp98 | 3.68 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.11 | 38.23 ± 0.10 | 41.56 ± 0.07 | 4.00 ± 0.03 | 1.44 ± 0.16 | 38.60 ± 0.05 | 41.01 ± 0.04 | Cβ |

| Glu104 | 4.39 ± 0.13 | 1.12 ± 0.26 | 33.13 ± 0.15 | 36.74 ± 0.17 | 4.51 ± 0.11 | 1.01 ± 0.17 | 33.02 ± 0.12 | 36.36 ± 0.14 | Cγ |

| Glu105c | 4.21 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 33.10 ± 0.08 | 36.79 ± 0.08 | 4.49 ± 0.17 | 1.04 ± 0.35 | 33.85 ± 0.18 | 36.33 ± 0.20 | Cγ |

| Glu110d | 4.50 ± 0.09 | 0.98 ± 0.19 | 34.34 ± 0.06 | 36.71 ± 0.08 | 4.31 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 32.65 ± 0.12 | 36.36 ± 0.10 | Cγ |

| Glu114 | 4.70 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 33.09 ± 0.06 | 36.97 ± 0.09 | 4.49 ± 0.09 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | 32.59 ± 0.13 | 36.58 ± 0.14 | Cγ |

| Asp115 | 4.15 ± 0.05 | 0.76 ± 0.06 | 38.18 ± 0.06 | 41.69 ± 0.05 | 4.18 ± 0.09 | 0.94 ± 0.16 | 38.10 ± 0.12 | 41.11 ± 0.11 | Cβ |

| Asp119 | 4.02 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 122.85 ± 0.08 | 125.87 ± 0.06 | 3.99 ± 0.02 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 123.27 ± 0.03 | 126.20 ± 0.02 | N |

| Asp121 | 4.62 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.08 | 39.11 ± 0.03 | 41.43 ± 0.06 | 4.39 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 117.42 ± 0.03 | 119.36 ± 0.03 | Cβ/Nb |

| Glu123 | 4.87 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 33.16 ± 0.05 | 36.95 ± 0.08 | 4.69 ± 0.10 | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 32.69 ± 0.13 | 36.46 ± 0.16 | Cγ |

| Glu126 | 4.89 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.18 | 32.53 ± 0.08 | 36.72 ± 0.14 | 4.55 ± 0.10 | 0.91 ± 0.16 | 32.03 ± 0.16 | 36.12 ± 0.19 | Cγ |

| Glu130 | 4.53 ± 0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 33.09 ± 0.09 | 36.82 ± 0.09 | 4.40 ± 0.09 | 1.09 ± 0.22 | 33.05 ± 0.14 | 36.38 ± 0.15 | Cγ |

| Glu131 | 4.58 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 33.26 ± 0.06 | 36.84 ± 0.07 | 4.71 ± 0.15 | 0.61 ± 0.12 | 32.80 ± 0.22 | 37.09 ± 0.27 | Cγ |

| Asp135 | 4.16 ± 0.07 | 0.70 ± 0.06 | 38.18 ± 0.08 | 41.74 ± 0.08 | 4.05 ± 0.06 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 37.88 ± 0.09 | 41.16 ± 0.07 | Cβ |

| Glu137 | 4.82 ± 0.16 | 0.56 ± 0.11 | 123.36 ± 0.11 | 125.77 ± 0.17 | 4.42 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 123.88 ± 0.02 | 125.56 ± 0.02 | N |

| Glu139 | 4.69 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 33.14 ± 0.06 | 36.99 ± 0.08 | 4.54 ± 0.06 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 32.72 ± 0.09 | 36.62 ± 0.11 | Cγ |

| α-CO2− | 3.65 ± 0.03 | 1.10 ± 0.07 | 8.537 ± 0.006 | 8.081 ± 0.003 | 3.67 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.06 | 8.541 ± 0.007 | 8.087 ± 0.005 | HN(A140) |

All values are for a temperature of 10°C.

The pKa values of Asp2 and Asp121 were determined from Cβ chemical shifts in the absence of salt and 15N chemical shifts in the presence of 150 mM salt.

Glu13, Glu46 and Glu105 titrate as a single unresolved group and the three residues are assigned the same parameters in the absence of salt. The pH titration of the three residues can be resolved in the presence of 150 mM NaCl.

The assignments for Glu35 and Glu110 are tentative due to spectral overlap and may be reversed.

pH titration parameters for αS are summarized in Table I. In the absence of salt, the pKa values of the 18 Glu residues in αS are spread over 0.8 pH units while those of the 6 Asp residues are spread over 1.0 pH units. The ranges are large for an unfolded protein and comparable to those of ionizable residues on the surfaces of folded proteins.37,39 The pKa values show a pronounced dependence on residue position in the amino acid sequence (Table I). Acidic residues within the first 100 amino acids of αS have lowered pKa values indicating a lower affinity for protons (hydronium ions) such that they resist losing their negative charge. Sites within the last 40 residues have raised pKa values indicating a higher affinity for protons, which would facilitate the neutralization of acidic residues in the C-terminal tail.

pKa values for αS in the presence of salt

Deviations of pKa values from random coil model compounds have been reported for other unfolded proteins36,37,39,40 and the differences were found to decrease with increasing salt concentration.38 To obtain data at a physiological salt concentration we characterized the pH titration of αS in the presence of 150 mM NaCl [Fig. 2(A,C)]. The analysis of the data were similar to those for αS in the absence of salt. We determined pKa values for 20 of 26 sites from 3D C(CO)NH experiments. The pH titrations of His50, Asp119, Glu137 and the C-terminal α-carboxyl group are not amenable to C(CO)NH spectroscopy and were determined using 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra (Table I). The pKa values for two additional residues (Asp2, Asp121) were determined from 15N shifts in 1H-15N HSQC spectra because of overlap in the C(CO)NH experiments. For αS in the presence of 150 mM NaCl we were able to resolve the pH titrations of all seven Glu(Cγ)-Gly(HN) spin systems, although the assignments of E35 and E110 remain tentative and could be reversed (Table I).

The spread of pKa values in the presence of 150 mM NaCl is smaller as exemplified by the representative titrations of residues E28 and E114 [cf. Fig. 2(B,C)]. The distribution of lowered pKa values in the N-terminal domain and raised pKa values in the C-terminal domain is less pronounced but persists when αS is studied in the presence of 150 mM NaCl (Table I).

Differences from random coil pKa values

To analyze the pKa data for αS we needed to obtain reference values for residues in random coil conformations. Random coil pKa values are available in the literature46–48 but to obtain accurate values for Glu and Asp residues, which account for 24 of the 26 ionizable sites in this study, we carried out 1H NMR pH titrations on the model peptides Ac-AADAA-NH2 and Ac-AAEAA-NH2 under the exact same conditions used for the pH titrations for αS. The two Hβ protons of the aspartate in the Ac-AADAA-NH2 peptide, which gave the same pKa within experimental uncertainty, were used to obtain an ionization constant for aspartate. The Hγ protons of the glutamate in the Ac-AAEAA-NH2, which have degenerate chemical shifts throughout the entire pH range studied, were used to obtain an ionization constant for glutamate. The random coil pKa values we obtained for aspartate were 4.00 ± 0.02 in the absence of salt and 3.94 ± 0.02 in the presence of salt at 10°C. For glutamate, the pKa values were 4.42 ± 0.02 in the absence of salt and 4.38 ± 0.02 in the presence of 150 mM NaCl at 10°C. Our values are somewhat higher than those determined using potentiometry of the same peptides at a temperature of 25°C in the presence of 100 mM NaCl48 (3.67 for Asp, 4.25 for Glu), although the recent revision49 of these values (3.94 for Asp, 4.3 for Glu) bring them closer to those determined in this work. Our values are in very good agreement with those reported for model peptides at 25°C by potentiometry (4.0 for Asp, 4.4 Glu)46 and NMR (3.84 for Asp, 4.32 for Glu).47 For histidine, which occurs only once in αS at position 50, we used a published random coil pKa of 6.54 ± 0.04.46–48 For the α-carboxyl group at the C-terminus we used a random coil pKa of 3.67 ± 0.03.48

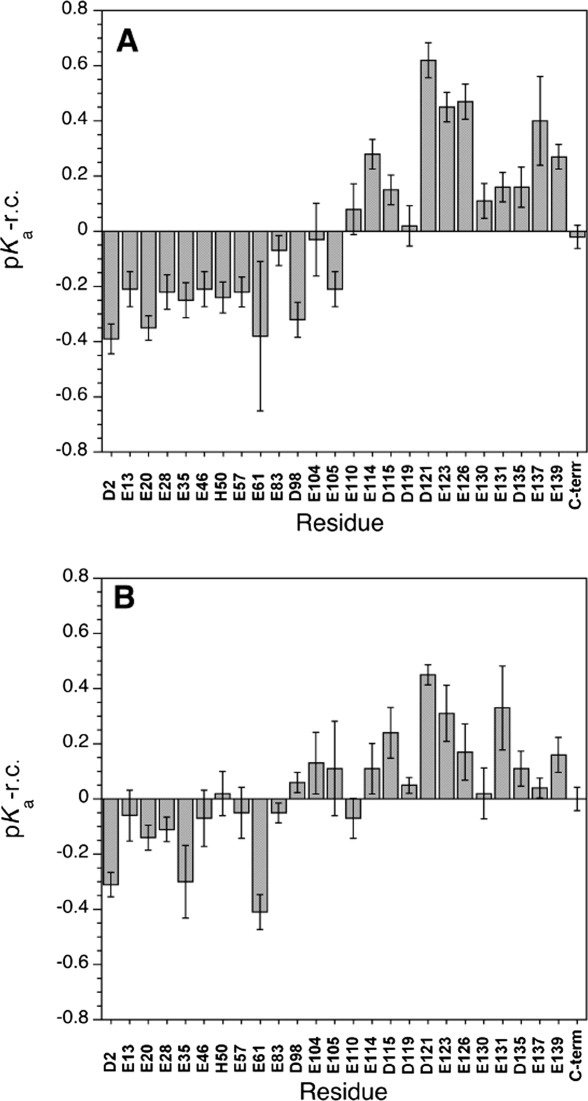

Differences between random coil and αS pKa values are shown in Figure 3(A) for the protein without salt and Figure 3(B) for the protein in the presence of 150 mM NaCl. Uncertainty bars were calculated from the propagation of standard errors from the least squares fits of the pH titration data for αS and the random coil peptides. Alternatively, if we consider that the primary source of error in the pH titrations is the accuracy of the pH measurements, which in our study is on the order of 0.05 to 0.1 pH units, the uncertainties in the pKa differences are between 0.07 and 0.14 pH units. Acidic residues from the N-terminal amphipathic domain of αS show uniformly negative differences [Fig. 3(A)] with pKa values lowered on average by 0.24 pH units from random coil values. In the C-terminal tail the differences are positive, with pKa values of acidic residues raised on average by 0.24 pH units compared to the corresponding random coil values. The switch-point from positive to negative differences occurs between residues Glu105 and Glu110, just outside the amphipathic and NAC domains, at the start of the acidic C-terminal tail. In the presence of 150 mM NaCl [Fig. 3(B)] the differences between αS and random coil pKa values are smaller but maintain the same pattern, with residues from the N-terminal domain showing negative differences (average = 0.10) and those from the C-terminus showing positive differences (average = 0.15). The switch-point in the sequence is harder to define but occurs near the demarcation of the amphipathic and acidic domains between residues D98 and E114.

Figure. 3.

Differences between αS and random coil pKa values (pKa, αS – pKa, r.c.). (A) αS in the absence of salt. (B) αS in the presence of 150 mM NaCl. The pKa values for αS are given in Table I. Random coil values were obtained from NMR titrations of the model peptides Ac-AAEAA-NH2 and Ac-AADAA-NH2 as described in the text. Random coil values for a histidine side-chain and the C-terminal α-carboxyl group were taken from published values.48 For His50 the difference was multiplied by -1 since this group gains a positive charge, in contrast to the acidic groups that lose a negative charge at low pH. All data are at a temperature of 10°C.

The N- and C-terminal domains also show small differences in the parameter n, the Hill coefficient for the pH titration. The Hill coefficient (Eq. 1) describes the cooperativity of pH titrations.50 Values of n less than 1 are associated with negative cooperativity, while n greater than 1 corresponds to positive cooperativity.50,51 The Hill coefficients for most sites in αS are very close to unity (Table I). Nevertheless, the average values for residues 1-105 are significantly larger than for residues 110-140: 0.98 versus 0.86 in the absence of salt (statistical significance, P < 0.03); 1.06 versus 0.84 (P < 0.01) in the presence of salt. The ionization of sites at the N-terminus thus appears to be more cooperative than at the C-terminus.

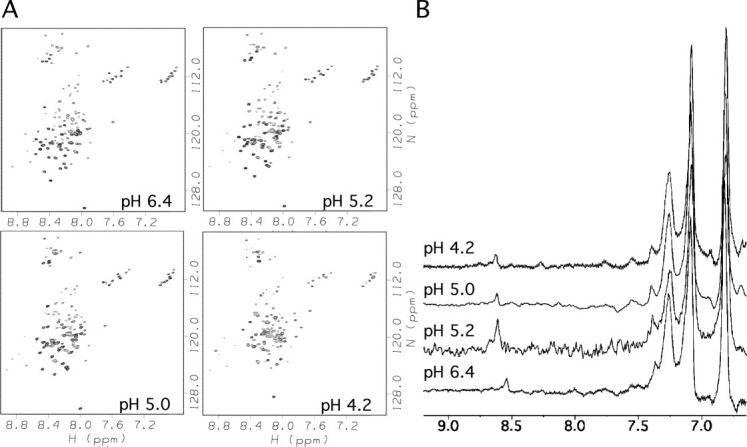

pH titration of His50 in αS bound to SDS micelles

When αS binds to an SDS micelle it forms an ∼32 kDa complex with an effective correlation time of 15.1 ns.16 The large size of the complex makes it technically difficult to characterize pKa values using C(CO)NH spectroscopy due to short T2 relaxation times, although this may be possible to circumvent at high magnetic fields using TROSY-based experiments in conjunction with perdeuterated αS samples. Another complication as shown in Figure 4(A), is that 1H-15N HSQC spectra of αS bound to SDS micelles deteriorate at low pH due to NMR signal broadening. This broadening is even more severe when the αS micelle complex is studied in the presence of 150 mM NaCl (not shown). The effects occur well above the pKa of the sulfate group in SDS52 which is at about pH 1.5, so we can conclude that the changes are associated with protonation of Asp and Glu residues in αS, although the mechanism of NMR line broadening is unknown. The transition has a mid-point near pH 5.2, about 0.8 and 1.2 pH units above the random coil pKa values of Glu and Asp, respectively. As we have described for amyloid-beta(1-40), the pKa values of acidic residues are uniformly raised in proteins bound to SDS micelles, due to electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged side-chains and negatively charged sulfate groups on the SDS micelles.53

Figure. 4.

Representative data from the pH titration of αS bound to SDS micelles. (A) 1H-15N HSQC spectra showing decreases in backbone 1H-15N correlation intensities below pH ∼5.2. (B) 13C-filtered aromatic spectra of αS in the presence of SDS showing the NMR signal of His50 Cɛ1 proton (near 8.6 ppm). Samples contained 0.25 mM αS and 50 mM SDS in 90% H2O/10% D2O, and spectra were recorded at a temperature of 37°C.

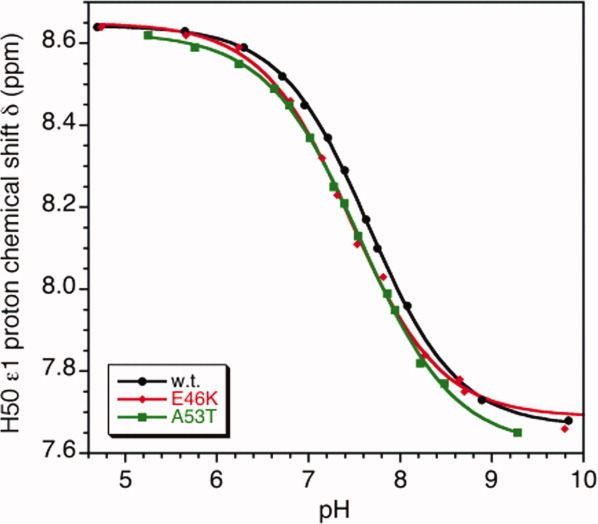

The aromatic Cɛ1 proton of His50 can be seen at low pH presumably because of the high flexibility of this side-chain in the complex [Fig. 4(B)]. In the WT αS bound to SDS micelles, His50 titrates with a pKa of 7.7, with the titration reaching a low-pH chemical shift plateau by pH 6.5 (Fig. 5) well before the broadening of crosspeaks in 1H-15N HSQC spectra below pH 5 [Fig. 4(A)]. The changes in the spectrum associated with the protonation of the C-terminal tail thus should not affect the pKa value obtained for His 50. Under similar conditions (37°C, 99.96% D2O) free αS has a pKa of 6.3.53 The pKa of His50 is thus raised by ∼1.4 pH units when WT αS binds to SDS micelles compared to the unbound state. The raised pKa of His50 indicates that protonation is facilitated in the micelle bound state, either because the charged form of the histidine ion-pairs with Glu46 in the α-helical structure adopted by the micelle-bound protein [Fig. 1(C)] or because the positively charged histidine interacts with the negatively charged sulfate groups of SDS.

Figure. 5.

pH titrations of the His50 Cɛ1 proton from αS bound to d25-SDS micelles. The samples contained 99.96% D2O solutions of 0.25 mM αS and 50 mM d25-SDS (0.8 mM micelles). All data were collected at 37°C. The pH values obtained in D2O were corrected for the deuterium isotope effect (pH = pHmeasured − 0.4) as described in the methods. The parameters obtained from least-squares fits of the titration data were: WT, pKa = 7.66 ± 0.01, n = 0.90 ± 0.02; E46K, pKa = 7.46 ± 0.03, n = 0.89 ± 0.06; A53T, pKa = 7.57 ± 0.02, n = 0.85 ± 0.02. For WT αS under the same conditions in the absence of SDS micelles,53 we obtained pKa = 6.33 ± 0.02, n = 0.99 ± 0.04. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

To distinguish between these possibilities we collected titration data for His50 in the Parkinson's disease-linked mutants E46K and A53T (Fig. 5). Glu46 is the only negatively charged residue positioned to form an ion pair with the charged form of His50 in the α-helical structure of micelle-bound αS. The E46K mutant, which replaces the glutamate with a positively charged lysine, gives a pKa of 7.5 for His50 in micelle-bound αS (Fig. 5). The pKa shift of −0.2 pH units from the WT is comparable to the shifts for residues positioned to form ion pairs in the N-terminal domain of uncomplexed αS (Table I, Fig. 3). For A53T the pKa shift of −0.1 pH units is intermediate and close to the experimental uncertainty. With both mutants, the pKa perturbations are much smaller than the difference of ∼1.4 pH units between free and micelle-bound αS. We can thus safely conclude that the pKa perturbation of His50 in micelle bound αS is dominated by the interaction of the histidine cation with the negatively charged sulfate groups on the surface of the micelle.

We looked for alternative membrane mimetics amenable to NMR studies of αS including micelles composed of the negatively charged lipid LPPG (1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-RAC-(1-glycerol)]), the neutral lipid LMPC (1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) and the neutral detergent DPC (dodecyl phosphocholine). Besides SDS, only LPPG gave a complete set of 1H-15N HSQC resonances for αS but the NMR spectra were of poorer quality than with SDS micelles (A.T.A and Andrew Mehta, unpublished results). High-quality NMR spectra have been recently demonstrated54 for αS complexed to micelles of the surfactant SLAS (sodium lauroyl sarcosinate) but like SDS and LPPG, the detergent is negatively charged and would be expected to perturb the pKa values of αS. With neutral DPC micelles, we confirmed that αS binds only weakly,19 such that most of the 1H-15N HSQC correlations from the N-terminal domain of αS are lost due to fast hydrogen exchange through the free form of the protein, which is in dynamic equilibrium with the micelle bound form. Since αS requires negatively charged lipids to bind to membranes we explored the amenability of mixed DPC/SDS micelles for NMR studies. Starting from micelles composed of the neutral DPC detergent we gradually added negatively charged SDS detergent. Above DPC:SDS molar ratios of 70:30 the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of αS were poor with most 1H-15N resonances lost due to fast solvent exchange. At a DPC:SDS molar ratio of 70:30 the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum was comparable to that of αS with pure SDS micelles16 but resonances were too broad for the more demanding C(CO)NH experiments used to determine pKa values. The enhanced solvent-exchange broadening of backbone amide protons under these conditions suggests that αS binds only weakly to micelles with DPC:SDS molar ratios of 70:30, so that even if we were to determine pKa values these would likely constitute a population weighted-average of the protein bound to micelles and a significant fraction of the free protein. Thus the characterization of pKa values for αS in a membrane-like environment is limited by the requirement of a small micelle size amenable to direct NMR studies, coupled with the requirement of micelles containing a high proportion of negatively charged lipids or surfactants that affect the ionization constants of titratable groups from the protein.

Discussion

The pKa values obtained for αS in this work show surprisingly large differences from random coil model peptides considering that the protein is intrinsically unfolded (Fig. 3). The results are consistent with previous findings that ionizable sites in unfolded proteins can have electrostatic environments that are poorly approximated by random coils.36,37,39,40,55 That αS adopts a highly unfolded structure in solution is supported by small chemical shift deviations from random coil values,22,23,28 averaged 3JHNHa coupling constants,22 fast dynamics as measured by 15N relaxation,23,56 largely averaged RDC values at least for the N-terminal domain,23,56 and rapid exchange of backbone amide protons with solvent.26 The long-range nature of electrostatic interactions allow weak charge-charge interactions to occur even though αS is highly unfolded, as evidenced by the lowered pKa values of the N-terminus, the raised pKa values of the C-terminus, and the salt dependence of the pKa values. We do not imply that these electrostatic interactions are the type of ordered hydrogen-bonded salt-bridges observed in X-ray structures of folded proteins. Rather these “nascent ion pairs” occur because of the positioning of oppositely charged acidic and basic residues in the KTKEGV repeats in the amphipathic domain, and because of electrostatic repulsion ensuing from the high density of negative charges in the C-terminal tail of the protein. Indeed theoretical work predicts perturbed pKa values for a Gaussian chain model of the protein staphylococcal nuclease due to the alternating arrangement of acidic and basic residues in the amino acid sequence, with these perturbations particularly strong for segments of the protein that form the α-helical structure in the native protein.57 Similarly, the present work demonstrates that electrostatic interactions governed by the placement of charged residues in the amino acid sequence can play a role in determining the properties of αS even though the protein is intrinsically unfolded.

Electrostatic repulsion between acidic groups in the C-terminal domain (residues 101-140) should have the effect of keeping this segment in extended, disordered conformations. Neutralization of the charges in the C-terminal tail by polycations58 or low pH22–24,58 enhances the aggregation and fibrillization of αS. It has been recently shown that neutralization of the C-terminal tail at acidic pH causes a conformational transition that leads to transient interactions between this segment and the nonpolar NAC domain. This state of αS aggregates with faster rates than the state populated at neutral pH.22–24 The conformational transition to the low pH state of αS leads to small changes in backbone chemical shifts of ∼0.3 ppm for the Cα carbons of residues from the C-terminus22,23 but is unlikely to affect the pKa measurements in the present study. First, the pH titrations of most residues in αS were followed by side-chain carbons which undergo much larger changes in chemical shifts with pH, on the order of 3 to 4 ppm (Table I, Fig. 2). The chemical shifts of side-chain carbons from acidic residues are affected by the protonation of carboxyl groups but are much less sensitive to any residual secondary structure in the protein. Second, the differences in pKa values correspond to differences in the midpoints of the pH transitions. The limiting low- and high-pH chemical shift plateau values of side-chain 13C resonances in αS are similar and show no dependence on residue position in the sequence (Table I). Deletion of the C-terminal tail by mutagenesis also enhances the rate of fibrillization.58,59 Functionally, the high density of negative charges may keep the C-terminal tail from associating with negatively charged lipids so that it is primed for recognition by its binding partners on the surfaces of membranes.

In contrast to the C-terminal tail, residues from the N-terminal domain show pKa values that are uniformly lowered compared to random coil models (Fig. 3). This behavior indicates that acidic residues from the N-terminal domain resist losing their negative charges, becoming neutralized at larger hydronium ion concentrations (lower pH) than the corresponding amino acids from the C-terminal tail of αS, or random coil peptides. The lowered pKa values suggest that the negatively charged acidic sites in the N-terminal domain form “nascent ion-pair interactions” with positively charged basic amino acids in the KTKEGV repeats. Although 150 mM NaCl screens these weak electrostatic interactions, they persist at a physiological salt concentration [Fig. 3(B)]. The observed average pKa shifts of −0.10 (with salt) to −0.25 (no salt) pH units for acidic residues in the N-terminal domain correspond to stabilizing ΔΔGtitr contributions of only −0.1 to −0.3 kcal/mol at 10°C. As such, the effects of individual ion pairs on the stability of α-helix structure in αS should be negligible. In analogy to other proteins, rather than stabilizing structure, electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged residues may be more important in nucleating the folding of α-helix structure.60,61 Once an ion pair is formed, it would allow localized folding which could then propagate α-helical structure through the rest of the N-terminal amphipathic domain. The slightly raised n values for the acidic residues in the N-terminal domain are consistent with cooperativity amongst the ionization reactions. Nucleation of αS folding could occur in the cytosol, with α-helical structures selected for membrane binding. Alternatively, the folding of α-helix structure may occur after the protein binds to the surfaces of lipid bilayers. In addition to facilitating folding of αS into an α-helix structure, nascent ion-pairs in the N-terminal domain may decrease the rates of misfolding of the protein into alternative toxic conformations. In this regard, it is interesting to note that reducing the number of KTKEGV repeats in αS increases the rate of fibrillization while increasing the number of repeats has the opposite effect.15

αS is primarily distributed in the cytosol.62 The membrane-bound protein which accounts for only ∼15% of synuclein in the brain, however, is probably the functional form, and membranes may play role in αS aggregation.7,62 The highest-resolution structural data for αS in a membrane-like environment has come from NMR but the technique is limited by the sizes and types of complexes that can be studied. Although indirect NMR studies have recently provided information on the interactions of αS with lipid assemblies as large as vesicles,21 direct NMR studies which afford the highest resolution and which are necessary for pKa measurements, require that the protein is tightly bound to lipid assemblies with sizes below ∼50 kDa.18 Micelles composed of the detergent SDS meet the requirements of tight association and small complex size for detailed NMR studies.18,27,63 For the purposes of investigating pKa values, SDS micelles pose the complication of presenting a high density of negative charges from the sulfate groups on the surface of the micelle. Studies with the Aβ(1-40) peptide show that SDS micelles strongly perturb the electrostatic properties of ionizable residues with both acidic and basic residues experiencing increases in pKa values of 1 to 2 pH units.53,64 These effects are specific to proteins and peptides, since the pKa of single amino acids are unperturbed in the presence of SDS micelles.64 The pKa shifts observed for proteins bound to SDS micelles, however, do not appear to depend on the context of the ionizable site within the protein structure or on the degree of interaction with the micelle.53

When αS is bound to SDS micelles, the pKa value of His50 is raised by 1.4 pH units compared to the free protein. The Parkinson's disease mutation E46K breaks the pattern of acidic residues alternating with basic residues with an i, i+3 or i, i+4 spacing in the N-terminal domain of αS [Fig. 1(A)]. To see if the raised pKa value of His50 in αS complexed to SDS micelles is due to an electrostatic interaction within the protein or between the histidine and the micelle, we obtained titration data for His50 in the micelle-bound form of the E46K mutant. In the E46K mutant, the pKa value of His 50 is lowered by 0.2 pH units from 7.7 to 7.5 but is still 1.2 pH units higher than the 6.3 pKa of the histidine in natively unfolded WT αS at 37°C. Based on these observations we conclude that there is only a weak charge-coupling between Glu46 and His50. The large pKa shift of His50 when αS binds to SDS micelles is due to ion pairing between the histidine cation and the anionic sulfate groups on the surface of the micelle. In a membrane where the density of negatively charged lipids is lower, the interaction between Glu46 and His50 may be stronger. Considering the sequence of αS [Fig. 1(A)] the possibility also exists that Glu46 could interact with Lys43 in addition or in lieu of His50. Lys43 occurs in the break between the two α-helices in the structure of αS bound to SDS micelles18 so that it is not positioned to interact with Glu46 [Fig. 1(B,C)] but the two residues could ion-pair when αS folds into an uninterrupted α-helix conformation.29,32

Materials and Methods

Materials

The peptides Ac-AADAA-NH2 and Ac-AAEAA-NH2 used to obtain random coil pKa values for Asp and Glu were prepared by solid-phase synthesis at >95% purity by NEO-Peptide (Cambridge, MA). Deuterated SDS (d25-sodium dodecyl sulfate) was from Cambridge Isotopes (Andover, MA). The chemical shift standard 2,2-Dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Site-directed mutagenesis of αS

The E46K and A53T mutants were prepared starting from the pT7-7/asyn-WT vector65 which was a gift from the Lansbury lab (Harvard Medical School). Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). For E46K, the forward primer was 5′-CC AAA ACC AAG AAG GGA GTG GTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CAC CAC TCC CTT CTT GGT TTT GG-3′. For A53T, the forward primer was 5′-GTG CAT GGT GTG ACG ACA GTG GCT GAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTC AGC CAC TGT CGT CAC ACC ATG CAC-3′. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange protocol, utilizing PFU Turbo Polymerase from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The PCR product was purified using digestion with the restriction endonuclease DpnI from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) at 37°C, followed by transformation into Stratagene E. coli BL21 (DE3)-pLysS cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequences of the αS clones were verified using Beckman Coulter CEQ 2000 Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing at the UConn Biotechnology facility.

Preparation of αS NMR samples

Expression and purification of αS was carried out according to published methods.26,66 Cells were grown in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 1 g/L 15N ammonium chloride and/or 3 g/L 13C-glucose, at a temperature of 37°C and a shaker speed of 250 rpm. Ampicillin (100 μg/mL) was used to select for the amp resistance marker in the pT7-7/asyn-WT vector, and 37 μg/mL chloramphenicol was used to maintain the pLysS copy number. When the cells reached an OD600 of 0.6, αS expression was induced by addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by sedimentation at 4°C for 30 min in a Sorvall GSA rotor operating at 3150 g. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT and a few crystals of RNase, DNase, and lysozyme) and was sonicated at 70% (pulse 45 sec, delay 15 sec) for 10 minutes on a Fisher Scientific Sonic Dismembrator Model 500. After sonication, the cell lysate was boiled for 20 min and the cell debris was separated by sedimentation for 30 min at 28,300 g (Sorvall GSA rotor) and a temperature of 4°C. The supernatant was boiled again for 20 min, taking advantage of the heat stability of αS to achieve partial purification from other proteins in the lysate,67,68 and the precipitate was removed by sedimentation for 30 min at 12,800 rpm and 4°C. The resulting supernatant was subject to ammonium sulfate precipitation (361 g/L) for 1 h while stirring at 4°C, followed by collection of the pellet containing αS by sedimentation for 30 min at 12,800 rpm, 4°C. The ammonium sulfate precipitate was resuspended in 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4 and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer, followed by application on an Amersham Q-Sepharose Fast Flow anion exchange column. A linear 1 M NaCl gradient was used to elute αS. SDS-PAGE was used to identify column fractions containing αS, the fractions were pooled and dialyzed for 24 h against 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4. The αS purified in this way was determined to be at least 90% homogeneous by 15% tricine gel electrophoresis and electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectroscopy. Final yields of purified αS were about 50 mg/L of E. coli culture. Before use, purified αS samples were stored at –80°C in 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4 containing 0.02% NaN3.

pH titrations

The pH titrations of free αS (Figs. 2 and 3), αS in the presence of SDS micelles (Fig. 4), and random coil model peptides were performed on samples dissolved in 90% H2O/10% D2O. All αS and peptide samples used in this study were initially in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4. The sample pH was adjusted by adding aliquots of 1 M HCl and NaOH stock solutions. For comparisons of the titration of His50 in WT αS, E46K-αS and A53T-αS in the presence of d25-SDS micelles (Fig. 5) samples were dissolved in 99.96% D2O and pH adjustments were made using 1 M stock solutions of DCl and NaOD.

Three-point electrode calibrations (pH 4, 7, 10) were done before each pH titration. Solution pH values were measured before and after each experiment with typical differences between measurements of 0.05 to 0.1 pH units. The average of the pH measurements before and after each NMR experiment was taken as the solution pH. We found that the following protocol reduces fluctuations in pH measurements before and after NMR experiments. The pH after the NMR experiment is measured by transferring the sample from the NMR tube to an Eppendorf tube. For the next pH value, acid or base are added to adjust the pH, the sample is stirred on a Vortex mixer, transferred to the NMR tube, and then back to the Eppendorf for the pH measurement before the NMR experiment. This minimizes pH fluctuations from traces of the sample before the pH adjustment that remain in the NMR tube. The same NMR tube, Eppendorf tube, and pipette for transferring samples were used throughout the entire pH titration. NMR samples were contained in 5 mm (Wilmad 535-pp) tubes, with a larger initial volume (0.75–1.0 mL) than the recommended 0.6 mL, to make up for sample losses due to pipetting and pH measurements during the titration.

For pH measurements in aqueous solution we used a Mettler Toledo (Columbus, OH) Inlab Micro pH glass electrode. For solutions containing SDS we used a PH46-SS probe metal electrode from IQ Scientific (Loveland, CO), since trace amounts of KCl from glass electrodes precipitate SDS. Glass electrodes are known to be self-correcting for the deuterium isotope effect, since the effect of D2O on pH is equal and opposite in sign to the effect of D2O at the pH electrode.64 We established, however, that this is not the case for the PH46-SS probe metal electrode used in these studies. First, we established that under identical conditions the pH titration of His50 measured on a 13C,15N-labeled αS sample in 90% H2O/10%D2O using 1D 13C-edited spectra gave a pKa value of 7.7 compared to the value of 8.1 obtained measured using 1D 1H-NMR of a natural abundance αS sample in 99.96% D2O. Both titrations were followed with a metal electrode and the difference of 0.4 pH units corresponds to the deuterium isotope effect.69 Second, we calibrated both the glass and metal electrodes with H2O buffers and compared readings on the two electrodes for a series of buffers prepared in D2O. The readings for D2O solutions spanning the range pH 2–10 were consistently 0.2–0.4 pH units higher for the metal compared to the glass electrode. The only experiments done in D2O in this work were the titrations of His50 in WT, E46K, and A53T αS complexed to SDS micelles (Fig. 5). Because unlike the glass electrode50,69 the metal electrode we used does not appear to compensate for the D2O isotope effect, the following correction was applied to the D2O data in Figure 5 measured with a metal electrode: pH = pHmeasured − 0.4.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were done on a Varian 600 MHz instrument equipped with a cryogenic probe. The αS concentration for all experiments was 0.25 mM. DSS was used as an internal 1H chemical shift reference standard for all experiments. 13C and 15N chemical shifts were referenced indirectly as described in the literature.70 The pH titration of 13C,15N-labeled αS in the absence of salt was characterized with twelve 3D C(CO)NH and 2D 1H-15N HSQC experiments recorded between pH 7.4 and pH 1.5. Eleven experiments over the same pH range were used to determine pKa values for αS in the presence of 150 mM NaCl. An additional four 2D 1H-15N HSQC experiments were recorded up to pH 8.1 for each titration, to define the high pH chemical shift plateau of the His50 backbone 15N resonance. Experiments on αS in the absence of micelles were done at 10°C to prevent loss of amide proton signals due to fast exchange with solvent.26 Experiments with αS in the presence of SDS micelles were done at 37°C since lower temperatures reduce the quality of NMR spectra.28

The peptides Ac-AADAA-NH2 and Ac-AAEAA-NH2, dissolved to 3 mM concentrations in 90% H2O/10% D2O were used to determine random coil pKa values for Asp and Glu. The titration of the peptides in the absence of salt was followed using twelve 1D 1H NMR spectra recorded between 6.7 and 1.7. For experiments in the presence of 150 mM NaCl ten spectra were obtained between pH 6.4 and 2.4. All peptide experiments were done at a temperature of 10°C for direct comparison with the αS experiments.

The titration of 13C, 15N-labeled αS in the presence of 50 mM SDS was characterized with 2D 1H-15N HSQC and 1D 13C-filtered aromatic spectra. Four representative pH points that show the deterioration of 1H-15N HSQC spectra below ∼pH 5.0 are shown in Figure 4. The titration of the His50 Cɛ1 proton in WT, E46K and A53T αS was followed by 1D 1H NMR using protein samples at natural isotopic abundance in the presence of 50 mM d25-SDS dissolved in 99.96% D2O. For each of the experiments at least twelve spectra were recorded between pH 10.0 and 4.6 (Fig. 5).

The following spectral parameters were used for NMR experiments. 1D 1H NMR spectra were collected with spectral windows of 8000 Hz digitized into 2048 complex points. 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired with 1H × 15N spectral windows of 6000 × 1380 Hz digitized into 1024 × 128 complex points. The total acquisition time for each spectrum was 10 min. Three dimensional C(CO)NH spectra were acquired with 1H × 13C × 15N spectral windows of 6000 × 8800 × 1380 Hz digitized into 1024 × 64 × 32 complex points. The total acquisition time for each spectrum was 12 h.

NMR data analysis

Identification of NMR signals over the pH range studied, was facilitated by published 1H, 15N, and 13C assignments for αS at pH 7,54 pH 3,22 as well as data on the pH dependence of αS NMR spectra from our lab.26 For 1D spectra, chemical shifts were obtained from the center of the peak envelope. For 2D and 3D spectra, 1D traces were extracted along the frequency of the nucleus of interest. The traces were phased as necessary, before measuring chemical shifts from the center of the peak envelope.

The pH dependence of chemical shifts was analyzed using nonlinear least squares fits of the data to the modified Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:50,71

| (1) |

where the pKa is the ionization constant, δlow is the low pH chemical shift plateau, δhigh is the high pH chemical shift plateau, and n is the apparent Hill coefficient. The parameters obtained from the fits and their associated standard errors are given in Table I.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Peter Lansbury and Dr. Michael J. Volles (Harvard Medical School) for the pT7-7/asyn-WT expression vector used in this work and Dr. Suman Jha for comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.George JM. The synucleins. Genome Biol. 2002;3:1–6. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-3-1-reviews3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclea neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2804–2815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02804.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellani S, Sousa VL, Ronzitti G, Valtorta F, Meldolesi J, Chieregatti E. The regulation of synaptic function by alpha-synuclein. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3:106–109. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.2.10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernandez-Chacon R, Schluter OM, Sudhof TC. Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell. 2005;123:383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper JD, Lansbury PT., Jr Models of amyloid seeding in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie: mechanistic truths and physiological consequences of the time-dependent solubility of amyloid proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood SJ, Wypych J, Steavenson S, Louis JC, Citron M, Biere AL. alpha-synuclein fibrillogenesis is nucleation-dependent. Implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19509–19512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cookson MR. The biochemistry of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:29–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J, Kao SY, Lee FJ, Song W, Jin LW, Yankner BA. Dopamine-dependent neurotoxicity of alpha-synuclea mechanism for selective neurodegeneration in Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:600–606. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda A, Mallory M, Sundsmo M, Honer W, Hansen L, Masliah E. Abnormal accumulation of NACP/alpha-synuclein in neurodegenerative disorders. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:367–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lansbury PT, Lashuel HA. A century-old debate on protein aggregation and neurodegeneration enters the clinic. Nature. 2006;443:774–779. doi: 10.1038/nature05290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomiyama H, Mizuta I, Li Y, Funayama M, Yoshino H, Li L, Murata M, Yamamoto M, Kubo S, Mizuno Y, Toda T, Hattori N. LRRK2 P755L variant in sporadic Parkinson's disease. J Hum Genet. 2008;53:1012–1015. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:492–501. doi: 10.1038/35081564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore DJ, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Molecular pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:57–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler JC, Rochet JC, Lansbury PT., Jr The N-terminal repeat domain of alpha-synuclein inhibits beta-sheet and amyloid fibril formation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:672–678. doi: 10.1021/bi020429y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulmer TS, Bax A, Cole NB, Nussbaum RL. Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9595–9603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrin RJ, Woods WS, Clayton DF, George JM. Interaction of human alpha-Synuclein and Parkinson's disease variants with phospholipids. Structural analysis using site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34393–34398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bisaglia M, Tessari I, Pinato L, Bellanda M, Giraudo S, Fasano M, Bergantino E, Bubacco L, Mammi S. A topological model of the interaction between alpha-synuclein and sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry. 2005;44:329–339. doi: 10.1021/bi048448q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bisaglia M, Trolio A, Bellanda M, Bergantino E, Bubacco L, Mammi S. Structure and topology of the non-amyloid-beta component fragment of human alpha-synuclein bound to micelles: implications for the aggregation process. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1408–1416. doi: 10.1110/ps.052048706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodles AM, Guthrie DJ, Harriott P, Campbell P, Irvine GB. Toxicity of non-abeta component of Alzheimer's disease amyloid, and N-terminal fragments thereof, correlates to formation of beta-sheet structure and fibrils. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2186–2194. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodner CR, Maltsev AS, Dobson CM, Bax A. Differential phospholipid binding of alpha-synuclein variants implicated in Parkinson's disease revealed by solution NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2010;49:862–871. doi: 10.1021/bi901723p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho MK, Nodet G, Kim HY, Jensen MR, Bernado P, Fernandez CO, Becker S, Blackledge M, Zweckstetter M. Structural characterization of alpha-synuclein in an aggregation prone state. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1840–1846. doi: 10.1002/pro.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClendon S, Rospigliosi CC, Eliezer D. Charge neutralization and collapse of the C-terminal tail of alpha-synuclein at low pH. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1531–1540. doi: 10.1002/pro.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu KP, Weinstock DS, Narayanan C, Levy RM, Baum J. Structural reorganization of alpha-synuclein at low pH observed by NMR and REMD simulations. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:784–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueda K, Fukushima H, Masliah E, Xia Y, Iwai A, Yoshimoto M, Otero DA, Kondo J, Ihara Y, Saitoh T. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding an unrecognized component of amyloid in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11282–11286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croke RL, Sallum CO, Watson E, Watt ED, Alexandrescu AT. Hydrogen exchange of monomeric alpha-synuclein shows unfolded structure persists at physiological temperature and is independent of molecular crowding in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1434–1445. doi: 10.1110/ps.033803.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandra S, Chen X, Rizo J, Jahn R, Sudhof TC. A broken alpha -helix in folded alpha -Synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15313–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eliezer D, Kutluay E, Bussell R, Jr, Browne G. Conformational properties of alpha-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1061–1073. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jao CC, Hegde BG, Chen J, Haworth IS, Langen R. Structure of membrane-bound alpha-synuclein from site-directed spin labeling and computational refinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19666–19671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807826105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao JN, Jao CC, Hegde BG, Langen R, Ulmer TS. A combinatorial NMR and EPR approach for evaluating the structural ensemble of partially folded proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8657–8668. doi: 10.1021/ja100646t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulmer TS, Bax A. Comparison of structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human alpha-synuclein and Parkinson disease variants. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43179–43187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trexler AJ, Rhoades E. Alpha-synuclein binds large unilamellar vesicles as an extended helix. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2304–2306. doi: 10.1021/bi900114z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georgieva ER, Ramlall TF, Borbat PP, Freed JH, Eliezer D. The lipid-binding domain of wild type and mutant alpha-synuclecompactness and interconversion between the broken and extended helix forms. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28261–28274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drescher M, van Rooijen BD, Veldhuis G, Subramaniam V, Huber M. A stable lipid-induced aggregate of alpha-synuclein. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4080–4082. doi: 10.1021/ja909247j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marqusee S, Baldwin RL. Helix stabilization by Glu-…Lys+ salt bridges in short peptides of de novo design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8898–8902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexandrescu AT, Evans PA, Pitkeathly M, Baum J, Dobson CM. Structure and dynamics of the acid-denatured molten globule state of alpha-lactalbuma two-dimensional NMR study. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1707–1718. doi: 10.1021/bi00058a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matousek WM, Ciani B, Fitch CA, Garcia-Moreno B, Kammerer RA, Alexandrescu AT. Electrostatic contributions to the stability of the GCN4 leucine zipper structure. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan YJ, Oliveberg M, Davis B, Fersht AR. Perturbed pKA-values in the denatured states of proteins. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:980–992. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tollinger M, Crowhurst KA, Kay LE, Forman-Kay JD. Site-specific contributions to the pH dependence of protein stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4545–4550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0736600100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitten ST, Garcia-Moreno EB. pH dependence of stability of staphylococcal nuclease: evidence of substantial electrostatic interactions in the denatured state. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14292–14304. doi: 10.1021/bi001015c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elcock AH. Realistic modeling of the denatured states of proteins allows accurate calculations of the pH dependence of protein stability. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1051–1062. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasia RM, Bertoncini CW, Marsh D, Hoyer W, Cherny D, Zweckstetter M, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, Fernandez CO. Structural characterization of copper(II) binding to alpha-synucleinsights into the bioinorganic chemistry of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4294–4299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407881102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grzesiek S, Anglister J, Bax A. Correlation of backbone amide and aliphatic side-chain resonances in 13C/15N-enriched proteins by isotropic mixing of 13C magnetization. J Magn Reson B. 1993;101:114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 44.London RE, Walker TE, Kollman VH, Matwiyoff NA. Studies of the pH dependence of 13C shifts and carbon-carbon coupling constants of [U-13C]aspartic and glutamic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:3723–3729. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pujato M, Navarro A, Versace R, Mancusso R, Ghose R, Tasayco ML. The pH-dependence of amide chemical shift of Asp/Glu reflects its pKa in intrinsically disordered proteins with only local interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nozaki Y, Tanford C. Examination of titration behavior. Methods Enzymol. 1967;11:715–734. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song J, Laskowski M, Jr, Qasim MA, Markley JL. NMR determination of pKa values for Asp, Glu, His, and Lys mutants at each variable contiguous enzyme-inhibitor contact position of the turkey ovomucoid third domain. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2847–2856. doi: 10.1021/bi0269512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thurlkill RL, Grimsley GR, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. pK values of the ionizable groups of proteins. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1214–1218. doi: 10.1110/ps.051840806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grimsley GR, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. A summary of the measured pK values of the ionizable groups in folded proteins. Protein Sci. 2009;18:247–251. doi: 10.1002/pro.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markley JL. Observation of histidine residues in proteins by means of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Acc Chem Res. 1975;8:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaslik G, Westler WM, Graf L, Markley JL. Properties of the His57-Asp102 dyad of rat trypsin D189S in the zymogen, activated enzyme, and alpha1-proteinase inhibitor complexed forms. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362:254–264. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lefebvre-Cases E, Tarodo de la Fuente B, Cuq JL. Effect of SDS on acid milk coagulability. J Food Sci. 2001;66:555–560. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheftic SR, Croke RL, LaRochelle JR, Alexandrescu AT. Electrostatic contributions to the stabilities of native proteins and amyloid complexes. Methods Enzymol. 2009;466:233–258. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)66010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rao JN, Kim YE, Park LS, Ulmer TS. Effect of pseudorepeat rearrangement on alpha-synuclein misfolding, vesicle binding, and micelle binding. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:516–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuhlman B, Luisi DL, Young P, Raleigh DP. pKa values and the pH dependent stability of the N-terminal domain of L9 as probes of electrostatic interactions in the denatured state. Differentiation between local and nonlocal interactions. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4896–4903. doi: 10.1021/bi982931h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bertoncini CW, Jung YS, Fernandez CO, Hoyer W, Griesinger C, Jovin TM, Zweckstetter M. Release of long-range tertiary interactions potentiates aggregation of natively unstructured alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1430–1435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407146102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou HX. Residual charge interactions in unfolded staphylococcal nuclease can be explained by the Gaussian-chain model. Biophys J. 2002;83:2981–2986. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75304-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernandez CO, Hoyer W, Zweckstetter M, Jares-Erijman EA, Subramaniam V, Griesinger C, Jovin TM. NMR of alpha-synuclein-polyamine complexes elucidates the mechanism and kinetics of induced aggregation. EMBO J. 2004;23:2039–2046. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vilar M, Chou HT, Luhrs T, Maji SK, Riek-Loher D, Verel R, Manning G, Stahlberg H, Riek R. The fold of alpha-synuclein fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8637–8642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712179105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kammerer RA, Schulthess T, Landwehr R, Lustig A, Engel J, Aebi U, Steinmetz MO. An autonomous folding unit mediates the assembly of two-stranded coiled coils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steinmetz MO, Jelesarov I, Matousek WM, Honnappa S, Jahnke W, Missimer JH, Frank S, Alexandrescu AT, Kammerer RA. Molecular basis of coiled-coil formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7062–7067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700321104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee HJ, Choi C, Lee SJ. Membrane-bound alpha-synuclein has a high aggregation propensity and the ability to seed the aggregation of the cytosolic form. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:671–678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eliezer D. Amyloid ion channels: a porous argument or a thin excuse? J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:631–633. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma K, Cancy EL, Zhang Y, Ray DG, Wollenberg K, Zagorski MG. Residue-specific pKa measurements of the Abeta-peptide and mechanism of pH-induced amyloid formation. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;120:8698–8706. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conway KA, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Ding TT, Williamson RE, Lansbury PT., Jr Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both alpha-synuclein mutations linked to early-onset Parkinson's disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:571–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McNulty BC, Tripathy A, Young GB, Charlton LM, Orans J, Pielak GJ. Temperature-induced reversible conformational change in the first 100 residues of alpha-synuclein. Protein Sci. 2006;15:602–608. doi: 10.1110/ps.051867106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jakes R, Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Identification of two distinct synucleins from human brain. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, Lansbury PT., Jr NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13709–13715. doi: 10.1021/bi961799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glasoe PK, Long FA. Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J Phys Chem. 1960;64:188–189. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Yao J, Abildgaard F, Dyson HJ, Oldfield E, Markley JL, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dames SA, Kammerer RA, Moskau D, Engel J, Alexandrescu AT. Contributions of the ionization states of acidic residues to the stability of the coiled coil domain of matrilin-1. FEBS Lett. 1999;446:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]