Abstract

Introduction: Narrative approaches to psychotherapy are becoming more prevalent throughout the world. We wondered if a narrative-oriented psychotherapy group on a locked, inpatient unit, where most of the patients were present involuntarily, could be useful. The goal would be to help involuntary patients develop a coherent story about how they got to the hospital and what happened that led to their being admitted and link that to a story about what they would do after discharge that would prevent their returning to hospital in the next year.

Methods: A daily, one-hour narrative group was implemented on one of three locked adult units in a psychiatric hospital. Quality-improvement procedures were already in place for assessing outcomes by unit using the BASIS-32 (32-item Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale). Unit outcomes were compared for the four quarters before the group was started and then four months after the group had been ongoing.

Results: The unit on which the narrative group was implemented had a mean overall improvement in BASIS-32 scores of 2.8 units, compared with 1.0 unit for the other locked units combined. The results were statistically significant at the p < 0.0001 level. No differences were found between units for the four quarters prior to implementation of the intervention, and no other changes occurred during the quarter in which the group was conducted. Qualitative descriptions of the leaders' experiences are included in this report.

Conclusions: A daily, one-hour narrative group can make a difference in a locked inpatient unit, presumably by creating cognitive structure for patients in how to understand what has happened to them. Further research is indicated in a randomized, controlled-trial format.

Introduction

I wanted to explore the possibility of incorporating narrative ideas into a conventional locked psychiatric unit in the southwestern United States. Narrative approaches emphasize a storied understanding of people's behavior1 rather than a categorical understanding such as conventional diagnoses provide.2 It seemed a worthy challenge to start a group that would involve patients who mostly had multiple repeated involuntary admissions to construct new frameworks for understanding their experiences and their recovery. In a narrative approach, current and future behavior is understood as following logically from the plot of the stories in which the person lives.3 Such understanding facilitates the construction of alternate stories, which leads to different and more desirable outcomes.

Howe wrote that no one belief system could reveal the entire truth.4 A story can capture multiple belief systems in ways that can lead to constructive behavior change. White stated that people experience problems because they are restrained in some way from taking a course that would ameliorate their distress. This is referred to as “negative explanation.”5 The population for which this group was designed was steeped in deterministic explanations of defective genes and chemical imbalances. Having alternate explanations that could empower them to make personal changes to prevent undesirable future outcomes could be helpful.

O'Neill and Stockell opened the way for therapists to apply narrative methods to nonfamily groups.6 When people in their groups discovered that they could challenge the subjugating story about themselves as defective, however minimally, they begin to develop an alternative knowledge, or a reauthored account, of their lives. Standard approaches, particularly in the field of cognitive behavioral therapy and serious mental illness,7 typically do not make reference to such techniques or constructions of therapy. If psychotherapists incorporate notions of subjugation into our work, then, as Mullaly8 suggested, we can attempt to use transformational knowledge to change society from one that creates and perpetuates poverty, inequality, and humiliation to one more consistent with values of humanism and egalitarianism.

Methods

Setting

The setting was a locked inpatient psychiatric unit in a hospital in the southwestern United States. The county funded the care of all patients (the majority) who were involuntarily admitted to the hospital on a petition for assessment as to whether they were dangerous to themselves or to others or were persistently and gravely disabled. Almost all patients were indigent and receiving public assistance in one form or another. I took over a group that had been a psychoeducational group provided by social workers. Because the average patient stayed 12 days (the median was six), each week would probably have to begin and end a whole sequence of groups, especially because the majority of patients were admitted on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday. The maximum size of the unit was 18 patients, and the sizes of groups ranged from 2 people to 14, with seemingly random fluctuations. The three locked units in the hospital were viewed as equivalent. Admissions were assigned to each unit in a manner that maintained equal census. Two psychiatrists were assigned to each unit. A fourth geriatric locked unit existed but did not contribute data to this project. Because patients were involuntarily admitted, the institution's ethics board determined that they could not give consent for participation in research. Therefore, the only acceptable way to study this population was to build on a pre-existing quality-improvement project in which assessments were made at admission and discharge without patient identity. Although we could know to which unit patients were assigned, we could not know which patients attended the group and which did not. Therefore, we had to assess the impact of running the group on the aggregate outcome data for units as a whole rather than on individuals attending the group versus individuals not attending the group. This prevented the use of some statistical procedures and weakened power to detect an effect. Nevertheless, it would be significant to show that the replacement of a psychoeducational group by a narrative therapy group had an impact on aggregate outcomes for the unit as a whole, compared with the other two units that continued to offer the psychoeducational group.

Design and Development of the Group

I built on Vassallo's design9 for a narrative group for the seriously mentally ill, which was an outpatient group meeting every two weeks with referred nonpsychotic patients. Unlike Vassalo's design, however, this study included acutely psychotic patients as well as others in crisis, and the group met daily. This choice is supported by research indicating that such patients could do well with group therapy approaches.6,9,10–27 Yalom27 traced the bias against group work for psychotic individuals to the psychodynamic perspective in which the leader was largely silent, provoking anxiety among the members. I implemented the concept of Coupland et al28 that group facilitators should “suspend disbelief” about the utterances of psychotic people because they may have truly remarkable stories to tell. All utterances of members were respected and deemed worthy of consideration, regardless of how delusional or psychotic from conventional perspectives.

I used Anthony's model of recovery,29 in which people can improve without professional help and professionals do not necessarily hold the key to getting better. Rather, the people themselves do. This concept was introduced in the group because most patients had had repeat admissions and did not seem to be getting better despite episodic professional help.

Anthony believed that a common denominator of recovery was the presence of people who believe in and stand by the person in need of recovery. The idea that they needed a community if they wanted to stop being readmitted to hospitals was introduced to the patients in the group.

Anthony believed that people who have or are recovering from mental illness are sources of knowledge about the recovery process and that these people can be helpful to others who are recovering. This idea was conveyed to people in the groups and it was emphasized that they could be helpful to each other and could learn from and inspire one another, even after discharge.

Previous groups on the unit had been psychoeducational groups7 in which people learned the importance of taking their medication. The group under study relied more on Reid's interactional model,30 in which group members help each other. The group emphasized members' actually recognizing that they had areas of competency. They could do that through observations of each others' descriptions of stories about successes and could be asked to produce their own stories of successes that challenged the dominant story of their defectiveness. In keeping with Northern's model,31 I emphasized an atmosphere of experimentation and flexibility.

In a narrative approach, current and future behavior is understood as following logically from the plot of the stories in which the person lives.3

The group design aimed to challenge the usual group model in which people talked about their deficiencies, focusing instead on the stories they brought to the hospital about how they got there and on what stories they might prefer to tell (about how they avoided a situation in which they could have been admitted to the hospital). The variety of people present in the group was presented as representing a diversity of perspectives from which each person could learn. The group aimed to help people reconnect with their own knowledge and strengths.32 In keeping with White and Epston's descriptions,1 the group was meant to be an environment to facilitate the generation of new life descriptions so that largely powerless people could feel some small sense of agency or control over their lives.

The group was meant to communicate to its members White's idea of problems developing an identity of their own, which then exerts influence on individuals, couples, families, and communities. The group was meant to introduce to this population White's concept33 of externalizing and separating from the problem so that the degree of its influence over the person could decrease.34 The group aimed to help people separate themselves from problems and see problems as things that affect them, things against which they can take action, rather than seeing themselves as the problem.32

The leaders planned to provide as much structure as necessary to keep the group flowing and to prevent loss of attention, very different from the typical psychoanalytic group.

The purposes for the group included the following:

To invite people who were involuntarily admitted with potentially serious conditions to inform others about their experience in a way that honored them as people and gave them a different experience

To place usually marginalized people in the role of providing guidance to one another in distinction to their usually experienced subjugated position of being given guidance and being told what to do

To help people discover alternative stories to the one leading to their hospital admission and consider how to live one of these stories to avoid future hospitalizations

To assist people to be more clear about when it is optimal for them to ask for help

To assist people in developing alternate, preferred stories that they could aspire to live that would bring them to a different life situation within a year from discharge. These stories would showcase previously hidden strengths and resources and would compete with the story they had been living of chronic disability and rehospitalizations.

The group was conducted by a social worker and a family physician/psychiatrist. It lasted one hour each day. Discussions about group content and process occurred only within the group at the time that issues emerged or in the final five to ten minutes of the group, with participants as active members of those discussions. All mental health technicians, activities therapists, nurses, and other physicians were invited to attend. Usually only one other person attended (besides the leaders), most commonly a mental health technician, and often because they were assigned to be within arm's length of a patient attending the group. All patients on the unit were strongly encouraged to attend, including psychotic patients, patients in acute distress, and patients going through withdrawal.

The group was conceived as a daily venture in introducing narrative concepts to the staff. Initially, all mental health technicians were going to be required to attend to learn narrative practices. The social work staff desired to attend, as did the activities therapists. In actuality, the mental health technicians did not attend, except when they were assigned to provide one-to-one staffing for a patient who did attend the group. Only one of the social workers regularly attended, along with intermittently both of the activities therapists, who then augmented the group by creating continuity from what was discussed in the group to what was done in their activity group.

We began by asking people to tell the story of how they were admitted to the hospital. Almost everyone could relate to this idea.

Typical Group Flow

The group aimed to create a different experience from what the patients usually encountered in the hospital. (For examples of the patients' experiences, please see sidebar: People's Stories.) We began by asking people to tell the story of how they were admitted to the hospital. Almost everyone could relate to this idea. Some people told simple stories, such as “the police brought me here.” Occasionally the group could extend this further and find out what had led the police to bring them to the hospital. Some identified people in their lives who might have called the police. Others could identify situations that had arisen that resulted in the police being called. Others called the police themselves, saying that they were suicidal or were thinking of hurting someone else. Many came for drug- and alcohol-related problems, becoming depressed and sometimes suicidal in relation to alcohol use or becoming psychotic in relation to use of amphetamines, cocaine, or other drugs. Some people could identify defining moments in which they took the first drink or smoked crack cocaine or crystal methamphetamine.

People's Stories.

The largest impact of our group was on the leaders. The group members came alive as interesting and resourceful people instead of as the labels usually foisted on them (“drug addict,” “alcoholic,” “burned-out schizophrenic”).

1. One woman, who was being considered for admission to the state hospital because her illness was thought to be so severe, told amazing stories of her skills at managing junkyard dogs. She was always brought along on trips to steal metal and other parts from junkyards because of these skills. She explained in detail the culinary preferences of the different species of dogs that guard junkyards. She told how she calmed a guard dog and made it lie down so that she could scratch its belly. The social worker asked her if there was one food that one should always take to the junkyard, and she answered, “Peanut butter.” Her skills were most impressive, though her take of the raid seemed less than commensurate with her considerable skill of getting her compatriots safely to their goal. As an example of the week's process, on the first day she wouldn't articulate how she got to the hospital. She said very little on Monday. On Tuesday, she was able to talk about the ambulance appearing at her apartment and bringing her to the hospital; she was not sure why it had. Wednesday was when she told the junkyard dog story. On Thursday, she was able to talk about how she might do better if she reached out to others and made friends instead of waiting for criminals to come to her for help stealing auto parts from junkyards as her only means of social contact. On Friday, she told a story of how she would like to tell group members in a year that she had made friends and that they came to check on her when it had been too long since she had come out of her apartment. The group helped her to explore how she might reach out to others to find friends.

2. Another man, labeled a hopeless heroin addict, told a story of having been clean and sober three years when he found Christianity and was living a Christian lifestyle. He had spent 22 of the past 25 years in prison and in and out of parole and probation, but for three years he had functioned very well. We learned that his downfall came when he started working away from home (and the support system of his church) with Mexican laborers on a roof project. Their habit was to drink beers after work. One day he acquiesced and joined them, and that evening of drinking led to a return to heroin use one week later. He believed that his downfall came when he left his daily church meetings to work in a city two hours away that required his staying in a motel surrounded by beer-drinking laborers. This helped the group form a story of recovery that might prevent that. On the second day, he was able to envision alternate stories: he could have stayed home; he could have gone to Alcoholics Anonymous in the new town; he could have found other things to do at night than drink. On the third day, he told the group several stories of times when he had relapsed and had gotten back on track. People questioned him carefully about how he did that; others in the group struggled with sobriety. On the fourth day, he named his alternatives and joined the group in an exercise of following each of three of them for a month. He decided from that exercise that going back to work with the laborers was a bad idea. The group supported most his plan of being a caretaker for a local church, which gave him a place to live and a small stipend. On Friday he told a story about meeting me one year later and proudly telling about staying clean and sober and working a whole year for the church, joining in Bible study, making friends who did not drink, and putting his past behind him.

3. Another woman, labeled as having hopeless borderline personality disorder, was enraged by the injustice of being taken to court to be ordered into treatment. She told her story in the group of being compliant with all of her treatment programs but being made worse by whatever medication she was given. She did not believe that she needed medication. When she was not taking medication, she worked at managing a convenience store and supported herself and her family. The medication made her sleep all day long. A story emerged of what appeared to be chronic misdiagnosis. The group helped her rehearse her story and eventually she presented it in group to her psychiatrist on the day before her court hearing. He was so impressed that he dropped the court proceedings and discharged her. On her first day, she was too angry to talk. On her second day, she ranted about the injustices done to her. On her third day, she told the group about her success at managing a convenience store and how proud she was when she brought home a paycheck. On the fourth day, she talked about wanting to go back to work at the convenience store and wanting to confront her psychiatrist about what she thought was a misdiagnosis and wrongly prescribed medication. We asked him to join the group on the fifth day. He did, and she told her story. After he left, she told us a story about being at the cash register one year later when one of us came to get gas and how proud she was about working and supporting her family so well.

4. Another man was admitted for being psychotic. When he told his story in group, all the members became convinced that he was indeed dangerous, but not because he was psychotic. Rather, he seemed to enjoy hurting other people. Though his story was unappealing to the leaders and all the other group members, we helped him rehearse it and also tell it to his psychiatrist, who became convinced that the man was just dangerous and not psychotic. This man was promptly discharged. He provided an example of one person's preferred story being so different from everyone else's preference that acute discomfort arose, yet we found a way to be nonjudgmental in letting him tell his story and organizing it in such a way as to present it to his physician. This man came to only the first three group sessions. On the first day, he told a story about a drug deal gone bad and how he decided to be suicidal so that the dealers he had ripped off would not kill him. On the second day, he told the group an alternate story of how he could have ambushed them and killed them first. On the third day, he told us a story about murdering someone and getting off with a plea of self-defense. This was the story that led the group to beg for his discharge.

The bias in the group was that everyone can find some sense of personal agency, however small. This served as a beginning for more personal agency and for more empowerment. Externalization was used to counter the idea that “I am bad and there is nothing I can do.” If we see problems as problems instead of people as problems, change is more possible. We maintained a valueless response about all possible solutions, focusing on following the story to learn the consequences of that solution and then deciding whether a particular story was a good one. In the beginning, the facilitator had to change the topic every ten minutes or so to keep the participants engaged; later in the program, more sustained attention was possible. It seemed that people learned how to engage in a process that was new to them. We were also engaged in collaborative topic-building and creating shared experience. We generally believed that patients' efforts, and not therapists' interventions, produced therapeutic change.

However important the relationship is, patients do the work, even with poor therapists.38

Next we asked people about other possible stories: What could have happened differently? We asked people to identify pivotal moments in which a different path could have been taken. This was harder, but many people could think of defining moments. What if another choice had been made at one of those defining moments? What could have been a different outcome? With some coaching, most people could relate to this. Examples included: “I could have called a friend instead of taking pills.”

This took most of the first two group sessions of the week. We wanted to put forth the idea that there were alternatives to the usual path followed (many had multiple previous admissions). Most of these patients were not used to using their imagination to think of alternatives. To be asked to do so was novel for them.

The third group session usually focused on having people tell a success story about themselves. The group searched for one time in participants' lives when they did something of which they or others were proud. The group focused on a time when they could remember doing something well. An example of a story that emerged came from a woman with multiple admissions living on the nearby reservation who felt that she was so worthless that someone should kill her. She recounted with pride the first time she was asked to sing in a sweat-lodge ceremony and described the sense of worthiness she experienced from being recognized as capable of singing well and of knowing the appropriate songs to sing.

The fourth group session of the week typically focused on making immediate postdischarge plans. The group members explored options and guided participants to develop a story about what would happen in the month after discharge in each of the various scenarios presented. One might consider this as a kind of anticipatory guidance.

The fifth group session of the week typically focused on the preferred story—what story would members wish to tell the leaders if they ran into us one year later in a grocery store parking lot? What did they wish they would be able to tell others?

Outcome Measure

The outcome measure was the BASIS-32 (32-item Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale),35 a patient self-report rating scale of symptom and problem difficulty, used primarily to assess treatment outcomes. It was already being used on admission for all patients in the hospital and was repeated before discharge. Having a hospitalwide outcome measure in place was helpful. Improvement was ascertained by comparing scores at admission with scores at discharge. The five domains measured by the BASIS-32 are psychosis, daily living/role functioning skills, relation to self/others, impulsive addictive behavior; and depression.36 Multiple confirmations of acceptable reliability and validity for the BASIS-32 have been conducted. A recent representative field test at 27 treatment sites across the United States assessed a total of 2656 inpatients and 3222 outpatients. Test-retest and internal consistency reliability were acceptable. Tests of construct and discriminant validity supported the instrument's ability to differentiate groups expected to differ in mental health status and its correlation with other measures of mental health.37

Results

Demographics

The mean age of patients responding to the quality-improvement scale for our hospital was 36, with 34% being female and 62% being white. Sixty-six percent had education beyond high school. The average length of stay was 12.4 days, with 72.2% involuntary admissions. The most frequent diagnosis was schizophrenia (27.2%), followed by depressive disorders (26.6%), bipolar disorder (22.4%), other psychotic disorders (6.6%), and substance-related disorders (6.6%).

Many felt betrayed by conventional psychiatry's promise of medications that would make them feel fine. They did not feel fine when taking medication.

BASIS Scores

The average change in patient-reported functioning on the BASIS-32 for all patients before the group began was 0.3; in patient-reported depression/anxiety, it was 0.5. The average change in psychiatric symptoms on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale was 5.1; on anxiety/depression rated symptoms, 1.8; and in overall functioning on the global assessment of functioning scale, 16.7. For the BASIS-32, on a standardized −4 to +4 scale for change from admission to discharge, where positive means improvement, the hospital as a whole showed a score of 1.0. The percent overall reporting satisfaction as excellent was 33.6%.

Outcomes

First I compared the unit's BASIS-32 scores with those of the other two adult locked inpatient units. No statistically significant differences were found in BASIS-32 change scores for admission to discharge for each the four quarters (12 months) prior to the start of the intervention. The last quarter was a baseline-monitoring period in which I spoke to the staff about the intervention and did trainings and presentations but did not begin.

Next, I compared changes in the total BASIS-32 scores for the whole hospital from admission to discharge for the quarter preceding the start of the group to the quarter during which the group was ongoing. The difference scores were normally distributed and met the required assumptions for a two-sample t-test with unequal variance. The mean discharge score for the hospital as a whole was 22.4 (SD, 8.4; 95% confidence interval [95 CI], 19.75–25.05) and for the unit was 18.4 (SD, 12.0; 95 CI, 13.92–22.88). The difference between discharge scores was −4.0. The comparison of discharge scores was not statistically significant (t = −1.566; p = 0.124), whereas the comparison of the admission to discharge differences reached borderline significance for two-tailed tests (p = 0.06) and was statistically significant for the one-tailed test (p < 0.05), which is justifiable if it is believed that participation could not make people worse.

The group tried not to define people as “mentally ill” but rather as people whose stories had resulted in hospitalization.

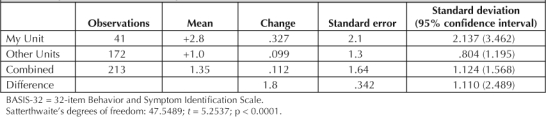

Finally, I compared the unit's results with those of the other two units for the quarter in which the intervention was taking place (knowing that there had been no statistically significant differences between units for the previous four quarters; Table 1). My group had a mean overall improvement in BASIS-32 scores of 2.8 units, compared with 1.0 units for the other two units. The results were statistically significant at the p < 0.0001 level. Naturally these results must be interpreted with caution because there might have been other reasons why our unit performed better than the other three units.

Table 1.

Two-sample t-test with unequal variances comparing our unit during the time of the narrative group for overall change score in the BASIS-32 with the scores for the other two units

Because this study actually had only 34.7% power to detect a statistically significant difference, the obtained p values are more impressive than they would initially seem (using the sampsi [“sample size”] command of Stata version 8.2 [StataCorp, College Station, Texas]). Eighty percent power would have required 106 people for the baseline and the same number of responders during the time in which the group was taking place. Subject sample size could be further reduced by including only people who actually attended the group, though this was not our original research question, or through the use of matched pairs.

Discussion

Throughout the three months of the group, people presented episodes in which they had challenged the prevailing story of them as defective and inferior. Virtually everyone could find a time when they had behaved differently from the expected story.

People readily identified with telling the story of how they came to be in the hospital. Most could tell at least one different story that would have prevented their coming to the hospital. Many had stories that illustrated times when they were successful or doing well. Harder was the idea of making up a story that they would like to tell if we ran into each other on the street one year later. This idea of a preferred story was more difficult. It appeared that this population was not encouraged in general to use their imagination and to fantasize alternate possibilities to the life they were leading. It was hard for them to imagine that their lives could be anything but inferior. They believed that they would always be disabled, should adjust to this reality, accept their Social Security disability income, and settle into the life of the chronically mentally ill. This appeared to be a terribly lonely, isolated, unfulfilling life. It was no surprise that many of them resisted the adjustment to this life by running away from their group home or other placement, by refusing to take medication, and by otherwise resisting those who regulated their lives. In the group, we were able at times to validate the meaning and purpose behind their resistance and their efforts to overthrow their label even as the group talked about the ways in which that resistance had not been successful in keeping them out of the hospital and to explore other, more potentially successful stories.

The idea of externalization was largely too difficult for group members to grasp over the course of one week, given their many years of involvement with the mental health system of learning and with a story of defectiveness. More than 70% of group patients had concomitant problems with substance misuse, and sometimes the group was able to talk about the use of substances as a means of reducing the misery, loneliness, and isolation of their conditions. They, like their physicians, were looking for the “magic bullet.” Many felt betrayed by conventional psychiatry's promise of medications that would make them feel fine. They did not feel fine when taking medication. This led to a search for drugs that would work, including methamphetamine (the apparent drug of choice in our area of the Southwest), cocaine, marijuana, heroin, and alcohol. Group members were clear about the usefulness of these substances in either anesthetizing themselves or in giving them a brief respite of pleasure in the face of a life of pain. For so many of our patients, their lives were miserable, and prescription medications could not be expected to offset the problems of powerlessness, abuse, threat, homelessness, isolation, and the biases of class and poverty.

We followed the ideas of the narrative model as much as possible in an effort to:

Emphasize personal agency for group members

Have the discussions about the group and about its members within the group for everyone to hear and join

Attempt to externalize the problems that had been defined as intrinsic or inseparable from the people having those problems.

Though we hoped to teach skills to mental health technicians for interacting with patients, no evidence emerged that this had happened. It appeared that interaction with patients was not actually a cultural value of the hospital. Typically mental health technicians read magazines, did puzzles, read newspapers, or otherwise occupied themselves when assigned one-to-one with patients. When supervising patients in the day room, they typically used the television or put on movies. This did not change as a result of the group.

The group leader found that he reported the most powerful effects, in that patients who had previously been puzzling to him began to emerge as more complete, complex people. In his previous role as inpatient psychiatrist, he had felt that his relationships with patients were mostly scripted by their expectations for how to behave with him and how he should behave with them. The group provided an opportunity for nonscripted behavior because many of the patients had other psychiatrists and had no need to cajole or influence him in any way. He found himself appreciating talents and resources for these patients much more than he had in his limited role as psychiatrist.

Virtually no effects on nursing staff members or other physicians were found.

Those patients who attended the group tended to come every day. They described the group as a welcome relief from the boredom of the unit. Some enjoyed hearing one another's stories. We had no way to obtain follow-up data from people after discharge. One member commented that the group had helped people to see that they had a more normal side. Members felt easy and comfortable in the group. As a group member said, “There was no pressure and no judgment.”

Most significant and rarely reported is how the group changed the leaders' experience. We felt more meaning and purpose at work. Our work was often a meaningless experience because we spent most of the time documenting people's histories with lengthy dictations and had little time to actually spend in dialogue with people except for the standardized questions that everyone had to be asked. The group provided a context from which to view the stories of patients' lives and to hear success stories and stories that could never come to light within the context of conventional psychiatry. Each of us looked forward to the group as a break from our usual routine. So many of our patients, who were repeaters, had no services or resources in the community and had to be discharged to essentially nothing. Others were lost in the substance misuse story and came to the hospital to dry out or detox or just for a break from drug use. Others were homeless and had learned to come to the hospital and say they were suicidal when things got too hard on the street. Because 72% of the study population was in the hospital involuntarily, it represented the most severe of the seriously mentally ill population. The ability of this group to participate in narrative practices, even while coming off drugs or being psychotic, was amazing and was a testimony to the power of story in people's lives.

The group tried not to define people as “mentally ill” but rather as people whose stories had resulted in hospitalization. We asked the question of how their stories could change to avoid hospitalization. Group leaders tried to introduce the idea of the importance of other people and community—in essence, to have an audience to support the story one would prefer to live.

We found that participation in the group for staff members encouraged them to “come down to earth” more. They found us having more direct and genuinely curious conversations with patients that were not couched in the usual power differential of staff versus patients. No one had to be at the group. People could leave at any moment. The criterion for staying was to want to stay. The staff members who did occasionally attend were amazed at the hidden richness of peoples' lives.

Participants did tell us how important it was to have staff (including physicians) who could listen and not discount the patient's knowledge. They did not like physicians who claimed to know more about them than they did or who discounted the side effects that they experienced from medications. They wished more physicians and nurses would have attended the group to see them from a different vantage and to hear their stories. They complained about how little time the physicians actually spent with them and how little some of the physicians seemed to care.

We were amazed at how naïve these patients were about psychosocial interventions of any kind. It appeared that they were mostly approached with case management and medications, and the idea of talking together and helping each other solve problems was largely ignored. Their attention span was short. Often, group leaders had to change topics every ten minutes on the first day of group (usually Monday) to keep people involved, but with increasing time in the group, attention spans increased. We did a few mindfulness exercises that could not be tolerated any more than five or ten minutes and seemed very strange to our participants, who nevertheless seemed to desperately need these techniques of stopping one's thoughts and sitting calmly in the present.

We suggest that further study is warranted with increased sample size to have adequate power to demonstrate a statistically significant effect. This study serves to introduce the topic and gives some guidelines for calculating sample size. We suggest a future study that includes measures of how the group affects staff and patients who attend, with the opportunity for follow-up after group members leave the hospital.

It appeared that this population was not encouraged in general to use their imagination and to fantasize alternate possibilities to the life they were leading.

Acknowledgments

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

References

- Epston D, White M.Literate means to therapeutic ends. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mehl-Madrona L.Narrative medicine: the use of history and story in the healing process. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Howe D. Modernity, post modernity and social work. Brit J Soc Work. 1994;24:513–32. [Google Scholar]

- White M. Negative explanation, restraint, and double description: a template for family therapy. In: White M., editor. Selected papers. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications; 1986. 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neil M, Stockwell G. Worthy of discussion; collaborative group therapy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. 1991;12(4):201–6. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, McGill CW.Family care of schizophrenia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mullaly R.Structural social work: ideology, theory and practice. Toronto, Canada: McLelland & Stewart; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo T. Narrative group therapy with the seriously mentally ill: A case study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. 1998 Mar;19(1):228–34. [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, el-Guebaly N. Group treatment for substance abuse in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1998 Oct;43(8):843–5. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiston DJ, Francey SM, Harrigan SM. Group programmes for recovery from early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172(33):117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres K, Pfammatter M, Garst F, Teschner C, Brenner HD. Effects of a coping-orientated group therapy for schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients: a pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000 Apr;101(4):318–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccheri R, Trygstad L, Kanas N, Waldron B, Dowling G. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Group experience in examining symptom management and behavioral strategies. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1996 Feb;34(2):12–26. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19960201-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free ML.Cognitive therapy in groups: guidelines and resources for practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gledhill A, Lobban F, Sellwood W. Group CBT for people with schizophrenia: a preliminary evaluation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1998;26:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin S, Nathan P, Drummond P, Castle D. A cognitive-behavioural, group-based intervention for social anxiety in schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000 Oct;34(5):809–13. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde P. Support groups for people who have experienced psychosis. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;64(4):169–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kanas N. Therapy groups for schizophrenic patients on acute care units. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988 May;39(5):546–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.5.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanas N. Group therapy with schizophrenic patients: a short-term, homogeneous approach. Int J Group Psychother. 1991 Jan;41(1):33–48. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1991.11490631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanas N.Group therapy for schizophrenic patients. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kanas N. Group therapy with schizophrenic and bipolar patients. In: Schermer VL, Pines M, editors. Group psychotherapy of the psychoses: concepts, interventions and contexts. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley; 1999. pp. 129–47. p. [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, Borak Y, Granek I. Cognitive group therapy for paranoid schizophrenics: applying cognitive dissonance. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1998;12(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schermer VL, Pines M, editors. Group psychotherapy of the psychoses: concepts, interventions and contexts. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Five questions about group therapy in long-term schizophrenia. Group Analysis. 1999;32(4):515–24. [Google Scholar]

- White JR, Freeman AS.Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for specific problems and populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Parr A, Landau S. Group treatment of auditory hallucinations. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:180–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID.In-patient group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Coupand K, Macdougall V, Davis E. With one voice: guidelines for hearing voices groups in clinical settings [serial on the Internet] New Therapist. 2004 Jul–Aug;32:18–24. [cited 2005 May 7]. Available from: www.newtherapist.com/32groups.html. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;16(4):11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reid KE.Social work practice with groups: a clinical perspective. Pacific Grove, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Northern H.Social work with groups. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McLean C, White C, editors. Speaking out … and being heard. 4th ed. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- White M. The externalizing of the problem and the re-authoring of lives and relationships. In: White M., editor. Selected papers. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications; 1989. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- White M. The process of questioning: a therapy of literary merit. In: White M., editor. Selected papers. Adelaide, South Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications; 1989. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- BASIS-32 Survey [monograph on the Internet] Belmont (MA): McLean Hospital; ©2002–07 [cited 2005 May 7]. Available from: www.basis-32.org/webscore/agreement.html. [Google Scholar]

- www.outcomes-trust.org/instruments.htm#basis [homepage on the Internet]. Waltham (MA): Medical Outcomes Trust ©2006 [cited 2007 Jun 26]. Available from: www.outcomes-trust.org/instruments.htm#basis (click on BASIS-32)

- Eisen SV, Normand SL, Belanger AJ, Spiro A, Esch D. The Revised Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-R): reliability and validity. Med Care. 2004 Dec;42(12):1230–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohart AC, Tallman K.How clients make therapy work: the process of active self-healing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]