Abstract

Objective: To present three outcome measures from a multiday residential Communication Skills Intensive provided to 525 clinicians in a large health care organization over ten years. The Intensive includes 10–12 hours of videotaped role-play with actors, extensive feedback, and self-reflection.

Methods: The background, content, and format of the Intensive are described. Results of three outcome measures are presented: program evaluations, a onetime physician satisfaction survey, and longitudinal patient satisfaction scores.

Results: A sampling of evaluations from three programs (n = 73) showed mean scores of 4.83 (on a Likert scale of 1–5) in response to the item “I will incorporate the skills acquired at this program into my clinical practice” and 4.90 in response to the item “Overall, this training was valuable.” On a follow-up physician satisfaction survey, nearly all (99%) of the 70 respondents indicated that the course had helped to improve their communication skills with patients. Most (89%) also said that applying the techniques they learned had increased their own professional satisfaction. Patient satisfaction scores for cohorts of course participants showed consistent increases in the six months following the course compared to the six months prior. This improvement has been sustained for as long as seven years.

Conclusion: Physicians have highly valued their participation in the Communication Skills Intensive. The impact of attending the course has been noticed by their patients. Offering physicians the opportunity for in-depth learning to enhance their interpersonal skills is a worthwhile investment for a health care organization.

Introduction

Three typical scenarios:

“I must be missing something. I thought my patients liked me.”.

Dr M is a 32-year-old internist who completed his residency two years ago. He prides himself on his thoroughness even though he usually runs an hour behind and stays late most nights to finish his charting. Being so dedicated to his patients, Dr M is shocked when his patient satisfaction scores are among the lowest in his department. His chief suggests that he attend the Communication Skills Intensive, a multiday residential program focusing on effective communication with patients. Though he questions the validity of his scores, he also feels angry—-at his patients, at the organization, and at himself. He decides to enroll in the Intensive, cautiously hopeful that he will better understand his patients' perceptions and find out how he can improve.

“I'm not very good at the touchy-feely stuff.”.

Dr B is a 51-year-old orthopedic surgeon who is regarded by his colleagues and his patients as having excellent technical skills. For most of his 18-year career, he has been rewarded for his successful surgical outcomes and high productivity. More recently, he has been told by his chief that he needs to improve his patient satisfaction scores and that too many of his patients file complaints saying that he is rushed, businesslike, and doesn't listen. He wants to achieve scores that would more accurately reflect his competence and he doesn't want to incur any financial penalty. Though he believes that he is “too old to change,” he signs up for the Intensive.

“I think I'm good at communicating with my patients, but I'm sure I have some blind spots.”.

Dr S is a 36-year-old pediatrician who enjoys her job running the adolescent medicine clinic and consistently gets high patient satisfaction scores. Since her chief attended the Communication Skills Intensive a couple years ago he has been encouraging each member of the department to enroll so that as a group they can communicate even better with patients, families, and each other. She has heard that it is an excellent program so she eagerly gets on the waiting list for the next course.

The three physicians described above represent many of the clinicians who have attended the Communication Skills Intensive in Northern California over the past ten years. Physicians in the first years of their career, like Dr M, can feel devastated when they receive low patient satisfaction scores. Seasoned physicians who get patient complaints like Dr B may feel defensive and skeptical. Other physicians seek to better handle difficult interactions or aim for general improvement in their interactions regardless of their patient satisfaction scores, like Dr S.

The Intensive is a 4- to 5-day residential clinician-patient communication program that includes videotaped role-play practice with actors. By working on customized scenarios with feedback from actors, faculty, and peers, participants in the Intensive gain insights about their interpersonal skills and learn strategies to communicate more effectively.

This article highlights the experience of 525 cliniciansa who attended the Communication Skills Intensive between 1996 and 2005. I describe the background, format, and content of the course and present three outcome measures: a brief summary of program evaluations, results of an online survey about the effect of the program on participants' communication behaviors and professional satisfaction, and patient satisfaction results from the regional Member Patient Satisfaction survey (MPS) tracked up to seven years following a program.

The story of the Intensive addresses several important questions: Can physicians change their communication habits by attending communication skills training? If physicians change how they interact, are patients more satisfied? Is improvement in patient satisfaction temporary or sustained over time? How does participation in an intensive communication skills course affect physician satisfaction? Is training physicians to communicate more effectively worth the investment?

Interventions to enhance clinician-patient communication must be effective in an environment of greater time constraints, new technology, and shifting consumer expectations. The outcomes resulting from the Communication Skills Intensive showcase the power of physicians to change, demonstrate that patients notice the changes, and provide a snapshot view of how communicating differently can enhance morale.

Methods

Background

Since 1990, when the first regionwide educational program on clinician-patient communication was instituted,1,2 The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) has shown strong commitment to enhancing the communication skills of its physicians. TPMG currently consists of more than 6000 physicians who serve over three million members of the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan in Northern California.

In 1994, the organization first distributed its MPS survey to Health Plan members after office visits. The MPS survey was developed and validated by survey experts within the organization. It includes a total of 25 questions, most of which address the patient's care experience: calling for an appointment, interacting with staff, seeing the health care professional, visiting lab and radiology, and filling a prescription. Physicians receive reports of their scores on the five questions that pertain to the patients' interactions with them. The questions ask patients to rate the quality of the physician's skills and abilities; their confidence in the care the physician provided; how well the physician listened and explained, involved them in decisions about their care, and showed familiarity with their medical history. Once distribution of individual scores became routine, questions arose as to how to assist physicians who scored below the mean calculated for their department. It was thought that existing one-day or lunchtime educational programs were not adequate to enable physicians to change the way they interacted with patients.

… participants in the Intensive gain insights about their interpersonal skills …

In 1995, the Board of Directors of TPMG approved the author's proposal to pilot a five-day residential program designed by the Bayer Institute for Healthcare Communication.3 The initial goal of the program was to improve the communication skills of physicians who fit any of four suggested criteria: low scores on the MPS survey, frequent patient complaints, medical-legal cases involving poor communication, and difficulty communicating with colleagues or staff. These criteria were meant to guide but not limit enrollment.

Over time, as early participants spoke enthusiastically about the program with their colleagues, physicians enrolled who were motivated to improve though they did not fit the criteria. The majority of the physicians who have attended the program, however, enrolled because of lower-than-desired patient satisfaction scores. Nearly all of the 22 courses have been full and wait-listed.

Program Description

The Communication Skills Intensive was piloted in March 1996. Because the pilot program was well received, the Intensive was established as an ongoing program conducted two or three times per year, starting in September 1996. Initially, the five-day residential course was followed by the opportunity for individual coaching monthly for one year, but logistical constraints prevented continuation of this coaching as intended.

The faculty consists of carefully selected and trained physicians and psychologists. Faculty members receive training from the course directors on models for teaching clinician-patient communication as well as training for leading small groups, setting up practice sessions with the actors, coaching, and addressing resistance. For the first several years, the ratio of course faculty to participants was 2:4; more recently, it has become 1:4.

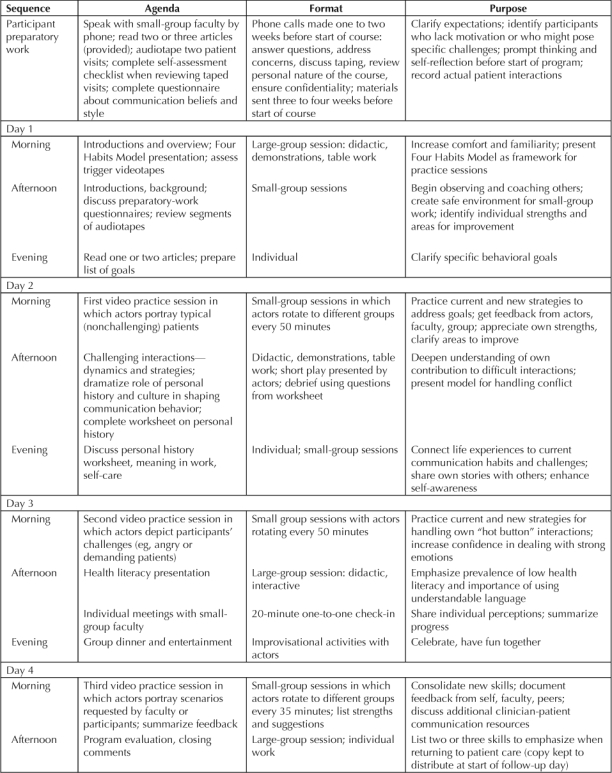

In Fall 2001, the residential part of the course was shortened to four days. The fifth day became a follow-up session conducted two to three months after completion of the residential program. The content and format of the four-day program are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of four-day intensive educational program for improving communication skills of physicians

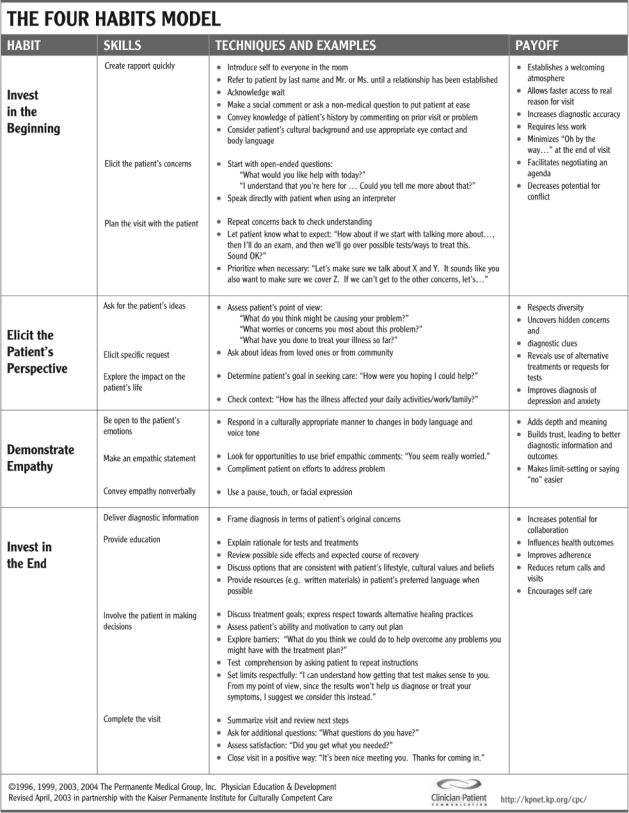

The design of the course attempts to reach both the minds and hearts of participants. Cognitive components of the program include a brief overview of the evidence about clinician-patient communication and its outcomes, description and demonstrations of a communication model—the course began to use the Four Habits Model (Figure 1)2 in 1998—and exploration of the dynamics of conflict and “hot buttons.” Strong emotions are often evoked during small-group discussions about personal history, culture, and meaning in one's work. These exchanges illuminate the connection between life experience and communication styles.4,5 Detailed feedback from faculty, peers, and the actors during the small-group role-play sessions enables course participants to begin assimilating new communication behaviors.

Figure 1.

The Four Habits Model.

Specific topics and methods of instruction in the large-group sessions have varied over time, although the structure and intent of the program have remained consistent. The overarching focus is on relationship-centered communication strategies that prove effective in the real world of a busy clinical practice.

The core constants of the program are:

10–12 hours of videotaped role-play with actors

use of a communication framework or model as the foundation

strong focus on handling difficult interactions

structured self-reflection

exploration of the link between personal history and current communication patterns

high faculty to participant ratio

a supportive, safe, and confidential environment

interactive teaching methods

reinforcement of learning after the course ends.

Strong emotions are often evoked during small-group discussions about personal history, culture, and meaning in one's work.

The follow-up day, two to three months after the residential program, includes: assessment of changes since the program (using copies of the goals written on Day 4), review of the Four Habits Model, two sessions of small-group role-play without actors, and a brief demonstration and didactic presentation on a new topic (such as cultural issues, telephone interactions, or using the computer in the examination room). Participants are expected to attend all five days.

The cost of the four-day residential program is approximately $3000 per participant. This amount covers room and board, materials, meeting costs, and a prorated contribution towards the expenses for the faculty and actors. Payment for each faculty member's time is an additional $500–800 per day. Participants use their own educational leave or vacation time to attend. All other costs are covered by TPMG Physician Education and Development.

Outcome Measures

Program evaluation: At the conclusion of each program participants completed an evaluation with both quantitative and qualitative questions. The quantitative questions asked about the likelihood of incorporating the skills into their clinical practice and for their rating of the value of the overall program.

Physician satisfaction: In October 2005, an online survey was e-mailed to the 118 clinicians who attended a Communication Skills Intensive in 2004 or 2005 to assess the effects of the course on their communication behaviors and on their professional satisfaction. Physician satisfaction following the program had not been measured previously.

Patient satisfaction: Participants' scores on the MPS survey have been tracked since 1998 (when a revised version of the original survey was implemented).b To maintain confidentiality, cohorts were formed by aggregating the scores of all of the clinician participants who attended the course each calendar year. These cohorts ranged in size from 37 to 60 clinicians each and totaled 322 clinicians for all cohorts combined.

Results

Participants

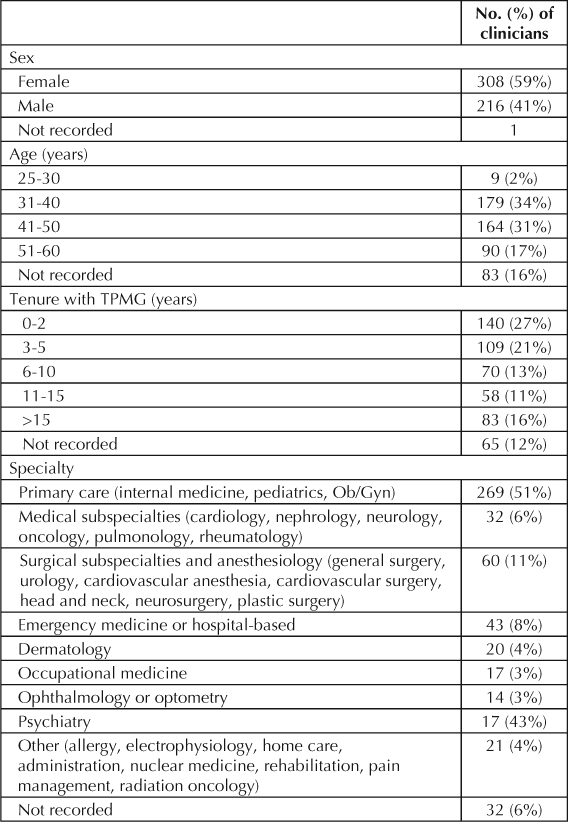

From 1996 through 2005, 525 TPMG clinicians attended the program (Table 2). These participants represented a broad spectrum of specialties, with 301 (57%) coming from primary care or medical subspecialties. Sixty (11%) were surgical subspecialists; 43 (8%) were hospitalists or emergency medicine specialists.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of 525 clinicians participating in the Communication Skills Intensive

An equal number of participants had worked in TPMG for two years or less (140) as had worked for more than ten years (141) at the time they took the course. The largest percentage of participants ranged from 31 years to 40 years of age. Thirty percent, however, were over 50 years of age, and 15% had worked in the organization for over 16 years.

Program Evaluations

Data collected from evaluation forms completed at the conclusion of each program have consistently shown positive results. For example, using a five-point Likert scale (on which 1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree), aggregate scores for three separate administrations of the course (n = 73) included a mean score of 4.83 in response to the survey item: “I will incorporate the skills acquired at this program into my clinical practice” and a mean score of 4.90 in response to the survey item “Overall, this training was valuable.”

Physician Satisfaction Survey

Of the 118 TPMG physicians who received the follow-up survey after attending the course in 2004 or 2005, 70 (60%) completed and returned the survey. Nearly all (99%) indicated that the course had helped to improve their communication skills with patients; 39% said the course had improved their skills “a lot.” When asked to describe what they were doing differently to communicate better with patients, respondents most commonly reported that they were using empathy, listening without interrupting, eliciting the patient's perspective, and structuring the visit. Specific comments included the following: “I understand how to listen actively to my patients. I express empathy to my patients a lot more frequently, and it really makes them satisfied with my care. I now have the tools to think through and analyze when some visits or interactions don't go well” and “[I now am] having a structure to the visit, emphasizing closure, [and] letting parents and patients do the talking without interruption.”

Most (88%) of the 70 respondents said that the course has had a positive impact on how patients respond to them during outpatient visits. Physicians noted that their patients more frequently expressed satisfaction with the visit, shared more information, and were less likely to escalate during potentially difficult interactions. One physician reported that patients seemed “much more engaged in the process, more welcomed into the process, happier with the outcome, and I am hearing from the primary care physicians that patients are conveying to them their greater satisfaction with my services.” Another physician noted that patients seemed “more appreciative and happier with the visits.”

Most (89%) also said that applying the techniques they learned has increased their own professional satisfaction. Many mentioned having greater confidence, feeling more appreciated, and having a stronger sense of connection with their patients. One physician reported, “[I have] much less stress with clearer boundaries. I generally leave work on time and leave work behind. I feel like I have more time in my day with more efficient visits/other means of communication. Members tell me that they feel heard and cared for. It's becoming a better partnership.” Another physician wrote, “I just feel better about coming to work; it's not a battle any more.”

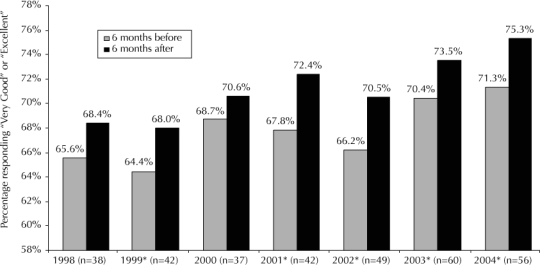

Patient Satisfaction Surveys

The MPS survey includes five questions about the interaction with the physician or health care professional (HCP). Scores on the survey are reported as the percentage of patients who indicated responses of “very good” or “excellent” on the following items: Your MD/HCP's skills and abilities, confidence in care MD/HCP provided to you, MD/HCP listened and explained, MD/HCP involved you in decisions about your care, MD/HCP familiar with your medical history. For each clinician, the combined scores for all five questions were averaged to generate the clinician's overall mean score.

For each cohort of physicians who attended the Communication Skills Intensive in 1998 through 2004, Figure 22 compares the mean combined scores for all five questions as determined six months before the course began and six months after the course ended. Five of the seven cohorts achieved a statistically significant increase (p < .05), and scores for all cohorts showed improvement over time.

Figure 2.

Member Patient Satisfaction Survey scores for cohorts of physicians six months before and six months after participating in Communication Skills Intensive course.

*p < .05 (Reproduced and adapted with permission of the author and publisher from: Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: A longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns 2005 Jul;58(1):4–12.2)

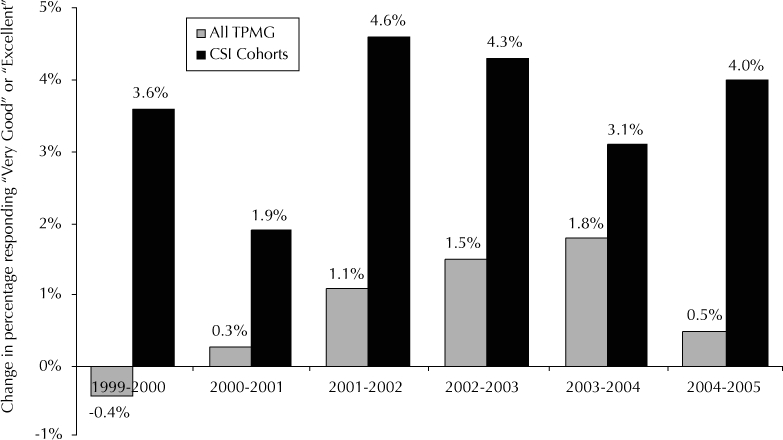

For the same span of years, Figure 3 compares the percentage change in the mean combined scores for all five questions for two sets of TPMG physicians: the cohorts in the present study (physicians who attended the Communication Intensive) and the population of all TPMG physicians for whom MPS scores were collected. The cohort scores for the course participants reflect improvement achieved in the six months after the course, compared with the six months before the course. Scores for the general population of TPMG physicians represent totals collected at the end of one year compared with scores collected at the end of the following year. (For example, the cohort of physicians attending the Communication Skills Intensive in 2001 improved their mean scores by 4.6% in the six months after the course, whereas the mean scores for TPMG physicians in the general TPMG population rose 1.1% from the end of 2001 to the end of 2002.) This comparison accounts for the regionwide changes occurring over each period of time and thereby approximates a control group of physicians who did not receive the intervention. Service enhancements introduced throughout TPMG (such as increased access to appointments with members' personal physicians and with specialists) contributed to a greater rate of improvement in survey scores between 2002 and 2004. Even during this period of regionwide increases in scores, our data show a pattern of substantially larger improvement for course participants.

Figure 3.

Twelve-month change in Member Patient Satisfaction Survey scores for general population of TPMG physicians (“all TPMG”) compared with change in survey scores among physician cohorts attending the Communication Skills Intensive course (“CSI Cohorts”).

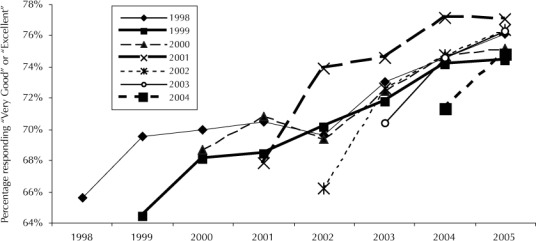

For each cohort of participants in the Communication Skills Intensive, Figure 4 presents the longitudinal mean combined scores for all five questions over time (through 2005). The greatest increases in scores occurred during the year after the course ended and between 2002 and 2004, probably reflecting the improvement observed regionwide during the same period.

Figure 4.

Mean Member Patient Satisfaction Survey scores for course participants over time (1998 through 2005).

Discussion

Our results show that physicians can change their communication habits by attending an intensive communication skills training that includes videotaped role-play practice with actors and extensive self-reflection. The changes lead to improvement in patient satisfaction, most pronounced in the 6–12 months after completion of the course and sustained for as long as seven years. Most physicians who attended the course found value in the experience and indicated that they would incorporate the skills they learned into their practice. A sampling of recent course participants reported positive changes in their post-course communication behavior with patients and enhanced professional satisfaction.

Several studies have documented measurable changes in physicians' communication behavior following communication skills training. After viewing videotapes of patient visits, Fallowfield et al6 reported that expressions of empathy, use of open-ended questions, appropriate responses to patient cues, and psychosocial probing were more frequent among physicians who attended a three-day course than among a control group. Follow-up videotapes recorded one year later showed that all of these behaviors endured except expressions of empathy.7 Similarly, Levinson and Roter8 showed that compared with baseline (pre-intervention) behavior, physicians asked more open-ended questions, more frequently solicited patients' opinions, and gave more biomedical and psychosocial information after attending a 2.5-day course on communication skills. Jenkins and Fallowfield9 also showed improvement in physicians' attitudes and beliefs toward psychosocial issues and in their self-reported awareness of their own style of questioning patients. The changes in physicians' attitude correlated with changes in their behavior.

… physicians can change their communication habits …

A systematic review of previous interventions designed to enhance physicians' communication skills in outpatient clinical settings identified eight studies that assessed patient satisfaction as an outcome of the intervention. (JK Rao, MD, personal communication, 2006)c In five of the eight studies, practicing staff physicians were the recipients of the educational intervention; in the other three studies, the intervention was given to medical residents. One study showed a postintervention increase in patient satisfaction;10 seven studies failed to show a difference in outcomes between experimental and control groups.11,12–17 One of these studies also reported that visit-specific physician satisfaction was unchanged after oncologists attended a three-day training course on clinician-patient communication skills.14 Hulsman et al18 measured patient satisfaction after providing computerized feedback to a group of physicians on their communication skills. Despite showing an increase in the quality of communication behavior after the intervention, the authors did not find an increase in patient satisfaction.

The data from our outcome measures add to this field of inquiry because of the large sample size of physician participants and their patients, tracking that uses a visit- and physician-specific patient satisfaction survey, initial scores in a range sufficient to show subsequent improvement, and our longitudinal follow-up. Because we did not study the real-time communication practices of course participants, our ten-year experience with the Communication Skills Intensive cannot tell us how the intervention leads to changes. Our longitudinal data on patient satisfaction and our snapshot of physician perceptions support one possible sequence: changes in attitudes and behaviors can be inferred to result from communication training and thus subsequently to lead to improved patient and physician satisfaction. Comments on the physician survey as well as the continuity in the patient satisfaction scores over time together indicate that for many participants the new skills they integrated into their clinical practices following the Intensive took hold and became habitual.

Our data have several limitations in addition to the lack of a formal control group. Attempts to construct historical control groups using patient satisfaction scores from physicians matched by specialty, tenure, age, and facility were unsuccessful. It is possible that controlling for the effects of familiarity and/or for the predictable increase in scores during a new physician's first three years of practice could have diminished or eliminated the improvement that we are attributing to attending the Intensive. Nonetheless, a strong level of reliability is suggested by two consistent patterns: substantial improvement in patient satisfaction as reported in the six months after the course ended, compared with satisfaction reported in the six months before the course began; and maintenance of this improvement over many years.

We were not able to track subsets of our yearly cohorts by their performance level on the MPS prior to enrollment. Designating participants in subsets would have given us a comparison of changes in patient satisfaction for physicians with low versus average or high scores. Also, the absence of directly observed or recorded interactions of participants precludes correlation of their behavior with the patient satisfaction scores. Another limitation is that the survey results regarding physician perceptions and satisfaction represent only a subset of course participants at a single point in time.

Is training physicians to communicate more effectively worth the investment? Our experience with the Communication Skills Intensive signifies that the investment of time, energy, and dollars is highly worthwhile. Participants have told us that after the course they change the way they communicate with their patients—they create new habits (See box: At the Communication Skills Intensive). They change how they interact with patients because the new behaviors become self-fulfilling. Many participants have described recapturing meaning in their work by enhancing connection with their patients. Longitudinal MPS results demonstrate that these changes are noticed by patients. Also impacted by better communication are accuracy of medical diagnoses, patients' adherence to prescribed treatment regimens, patients' health outcomes, physicians' medical-legal risk, and overall satisfaction of patients and physicians.19–24

At the Communication Skills Intensive.

Dr M discovered that his quest to offer comprehensive care to each of his patients often resulted in his asserting his own agenda for the visit and not paying adequate attention to his patients' questions and concerns. He found that using open-ended questions and planning the visit enabled him to hear about patients' issues while still keeping a sense of control. He also learned how to slow down the pace of his speech, use simpler vocabulary, and log onto the computer only after taking a moment or two to create rapport with the patient. Dr M became better aware of how to use his strengths: his obvious caring and commitment to his patients, his strong nonverbal skills, and his natural empathy.

Dr B struggled to break out of his biomedical approach to patient interactions. He was reluctant to be “too touchy-feely” at first. Feedback from the actors enabled him to see that patients who are intimidated by his take-control style may not understand his explanations and have worse outcomes. He also was beginning to understand that competently responding to his patients' emotions was actually part of his job. Once he took this feedback seriously, he was quickly able to explore new ways of interacting, even keeping his equanimity when an actor-patient burst into tears.

Dr S worked on some of the communication challenges unique to adolescent medicine. She learned new strategies for talking with anxious parents, discussing confidentiality with parents and teens, and giving bad news. She also developed a more effective way to collaborate with obese teenagers about diet and exercise.

Conclusion

Though numerous studies have shown that interactive (nondidactic) continuing medical education, such as the Intensive, can be effective in changing physician performance,25 our experience with the Communication Skills Intensive is the first time that such a large number of physicians have taken part in an organization-sponsored multiday residential clinician-communication program and then have been followed for so many years. The story of the Intensive tells us that when physicians are given an in-depth opportunity to explore their communication skills in a supportive and safe environment, physicians, patients, and health care organizations all benefit.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Philip Bellman, MPH, and Janet Ban, BA, for technical assistance and Vaughn F Keller, MFT, EdD, for creating the original design of the course. Editorial assistance was provided by the Medical Editing Service of The Permanente Medical Group Physician Education and Development Department.

Footnotes

a The majority of participants have been physicians, although nurse practitioners, psychologists, and optometrists have also attended.

b MPS surveys are mailed continuously throughout the year to a random sample of patients approximately two weeks after an outpatient visit. Results are formally reported twice a year for individual physicians. The goal is to receive at least 100 returned surveys per physician per year (standard deviation for N = 100 and a rating of 75 is ±8.5 points).

c Jaya K Rao, MD, MHS; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: Rao JK, Anderson LA. Abstract: Improving physician and patient communications skills in outpatient settings: lessons learned from intervention research. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:167–8.

References

- Stein TS, Kwan J. Thriving in a busy practice: physician-patient communication training. Eff Clin Pract. 1999 Mar–Apr;2(2):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2005 Jul;58(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller VF, Carroll JG. A new model for physician-patient communication. Patient Educ Couns. 1994 Feb;23:131–40. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, Epstein RM, Najberg E, Kaplan C. Calibrating the physician: personal awareness and effective patient care. Working Group on Promoting Physician Personal Awareness, American Academy on Physician and Patient. JAMA. 1997 Aug 13;278(6):502–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999 Sep 1;282(9):833–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002 Feb 23;359(9307):650–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Solis-Trapala I. Enduring impact of communication skills training: results of a 12-month follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2003 Oct 20;89(8):1445–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W, Roter D. The effects of two continuing medical education programs on communication skills of practicing primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1993 Jun;8(6):318–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02600146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Can communication skills training alter physicians' beliefs and behavior in clinics? J Clin Oncol. 2002 Feb 1;20(3):765–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CC, Pantell RH, Sharp L. Increasing patient knowledge, satisfaction, and involvement: randomized trial of a communication intervention. Pediatrics. 1991 Aug;88(2):351–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langewitz WA, Eich P, Kiss A, Wössmer B. Improving communication skills—a randomized controlled behaviorally oriented intervention study for residents in internal medicine. Psychosom Med. 1998 May–Jun;60(3):268–76. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos SK, Hickam DH, Gordon GH, Baker LH. Effects of a physician communication intervention on patient care outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996 Mar;11(3):147–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02600266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Boles M, Mullooly JP, Levinson W. Effect of clinician communication skills training on patient satisfaction. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Dec 7;131(11):822–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-11-199912070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling V, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Factors affecting patient and clinician satisfaction with the clinical consultation: can communication skills training for clinicians improve satisfaction? Psychooncology. 2003 Sep;12(6):599–611. doi: 10.1002/pon.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998 Jan 15;128(2):118–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RF, Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH. Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2001 Nov 2;85(9):1273–9. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger J, Thom D, MaCurdy T. Effects of a self-administered previsit questionnaire to enhance awareness of patients' concerns in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1997 Oct;12(10):597–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsman RL, Ros WJ, Winnubst JA, Bensing JM. The effectiveness of a computer-assisted instruction programme on communication skills of medical specialists in oncology. Med Educ. 2002 Feb;36(2):125–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995 May 1;152(9):1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985 Apr;102(4):520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997 Feb 19;277(7):553–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Jacob J, Schlenk E. Patient adherence to treatment regimen. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Maywah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Taranta A, Friedman HS, Prince LM. Predicting patient satisfaction from physicians' nonverbal communication skills. Med Care. 1980 Apr;18(4):376–87. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M, Greene JY, Mamlin JJ. The impact of clinical encounter events on patient and physician satisfaction. Soc Sci Med [E] 1981 Aug;15(3):239–44. doi: 10.1016/0271-5384(81)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999 Sep 1;282(9):867–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]