Abstract

Allostery is vital to the function of many proteins. In some cases, rather than a direct steric effect, mutual modulation of ligand binding at spatially separated sites may be achieved through a change in protein dynamics. Thus changes in vibrational modes of the protein, rather than conformational changes, allow different ligand sites to communicate. Evidence for such an effect has been found in TRAP (trp RNA-binding attenuation protein), a regulatory protein found in species of Bacillus. TRAP is part of a feedback system to modulate expression of the trp operon, which carries genes involved in tryptophan synthesis. Negative feedback is thought to depend on binding of tryptophan-bound, but not unbound, TRAP to a specific mRNA leader sequence. We find that, contrary to expectations, at low temperatures TRAP is able to bind RNA in the absence of tryptophan, and that this effect is particularly strong in the case of Bacillus stearothermophilus TRAP. We have solved the crystal structure of this protein with no tryptophan bound, and find that much of the structure shows little deviation from the tryptophan-bound form. These data support the idea that tryptophan may exert its effect on RNA binding by TRAP through dynamic and not structural changes, and that tryptophan binding may be mimicked by low temperature.

Keywords: conformation, dynamic allostery, protein dynamics

Abbreviations: DTT, dithiothreitol; rmsd, root mean square deviation; L-Trp, L-tryptophan; TRAP; trp RNA-binding attenuation protein; TRAPste, TRAP from Bacillus stearothermophilus; TRAPsub,TRAP from Bacillus subtilis

INTRODUCTION

Allostery, the energetic coupling of different ligand-binding sites on a protein molecule or complex, is central to the regulation of many pathways in living systems. From the early 1960s, when the MWC (Monod–Wyman–Changeux) [1] and KNF (Koshland–Némethy–Filmer) [2] models were proposed, allostery has been understood in terms of structural changes. In 1968, Kotani pointed out that thermodynamically there is no need to invoke such changes to bring about an allosteric effect, but his paper went largely unrecognized [3]. Since Cooper and Dryden [4] revived the concept of allostery without conformational change, a number of theoretical [5–8] and experimental [9–11] works have supported the idea that ligand binding to a protein may exert an effect through changes in dynamics rather than conformational changes; however, the detailed mechanisms are still not fully understood in any protein system.

TRAP (trp RNA-binding attenuation protein) is a highly thermostable, ring-shaped homo-11mer with a molecular mass of approx. 91 kDa [12]. It binds both tryptophan and RNA, and so offers an interesting opportunity to study complex allosteric effects and their role in control of processes in the cell. We have previously addressed the question of homotropic allostery in TRAP, the effects of tryptophan occupancy on other tryptophan-binding sites [13]. In the present study we examine how binding of tryptophan to the protein controls the ability of TRAP to bind RNA, apparently switching it from a non-RNA-binding form to a RNA-binding form. The X-ray crystal structures of tryptophan-bound TRAP from mesophilic Bacillus subtilis (TRAPsub) and thermophilic Bacillus stearothermophilus (TRAPste) have been solved [14,15] and include RNA-liganded forms [16–18]. These two proteins have identical ligand-binding sites and share high sequence and structural homology {TRAPsub shares 77% sequence identity with TRAPste and residues 8—73 have a rmsd (root mean square deviation) of 0.5 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) for main-chain atoms [15]}. All crystal structures to date have been in the presence of bound tryptophan, since the apo-form does not readily form crystals sufficiently ordered for X-ray analysis.

The role of TRAP in tryptophan synthesis has been extensively studied [19]. Briefly, when intracellular levels of tryptophan are high, tryptophan binds to TRAP, making the protein able to bind to a specific sequence in the mRNA leader sequence of the trp operon. This binding prevents formation of an RNA anti-terminator hairpin and promotes formation of a terminator hairpin structure, halting transcription of the operon and therefore limiting further synthesis of tryptophan. This system is further modulated in B. subtilis by the protein anti-TRAP which binds around the outside of the TRAP ring, blocking the RNA-binding site [20]. How tryptophan binding subsequently affects RNA binding is not fully understood.

Each TRAP monomer consists of seven β-strands, labelled A–G, connected by short loops. The tryptophan-binding pocket has been extensively characterized and consists of residues within the BC loop (residues 25–31) and DE loop (residues 47–53) (Figure 1). The indole ring is buried in a hydrophobic pocket and covered by the BC loop, with Thr30 forming a hydrogen bond to the primary amine nitrogen atom of the tryptophan. TRAP binds RNA through three positively charged residues on the outside of the ring, Lys37, Lys56 and Arg58.

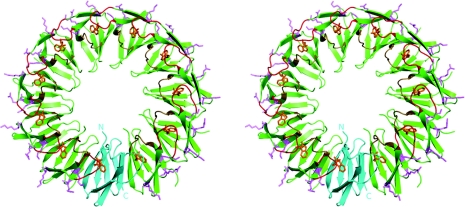

Figure 1. Stereoview showing the overall structure of tryptophan-bound TRAPste (PDB code 1QAW).

The structure is shown in cartoon format. A single monomer is coloured cyan and has the N- and C-termini labelled. Remaining monomers are coloured green. Pink residues shown as sticks on the outside of the ring correspond to the RNA-binding KKR motifs. BC loops are coloured red and DE loops are coloured beige. Tryptophan is coloured orange and shown in stick representation.

Tryptophan binding to TRAP shows only a small change in the Gibbs free energy of binding over a 25–50 °C range, with binding becoming gradually weaker as the temperature increases [21]. TROSY (transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy) NMR studies have shown that the flexibility of the protein increases in the absence of tryptophan, and that this dynamic disorder is centred around the tryptophan-binding pocket, particularly the BC loop [22] and the RNA-binding residues, resulting in a protein incapable of binding RNA. Tryptophan binding is thought to lead to stabilization of disordered regions, a decrease in protein dynamics and emergence of RNA-binding ability [22]. Modelling studies support these findings, suggesting that, in the absence of tryptophan, the motions of the regions surrounding the tryptophan-binding site are significantly increased [23].

These data have led to a model [22] in which the absence of tryptophan increases internal motion within TRAP, in particular with respect to the BC and DE loops. The increased flexibility presumably helps tryptophan to gain access to the binding pocket. Tryptophan binding stabilizes the BC and DE loop regions, with the rigidification propagating to the three positively charged residues involved in RNA binding in the C and E β-strands, switching on RNA binding.

In the present study we have investigated TRAP binding to RNA in the presence and absence of tryptophan, and also solved the crystal structure of tryptophan-free TRAP. These data support the dynamic model of TRAP and reveal interesting thermodynamic effects. Not only is TRAP a model system for understanding protein dynamics and allostery, but it is also being developed as a fundamental building block of self-assembled protein nanodevices [13,24,25] and can be engineered to form nanotubes [26]. A more detailed understanding of the dynamics of the protein under different conditions and the effect of ligand binding will be of interest to both areas of research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of TRAP

The gene encoding TRAP protein from B. stearothermophilus was sequence-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli by Genscript. The genes encoding TRAP were cloned into pET21b (Novagen) at the NdeI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites such that the NdeI site (CATATG) included the initiator methionine codon. TRAP was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Cells were resuspended in a buffer comprising 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) and 50 mM NaCl, and lysed by sonication, followed by centrifugation at an average RCF (relative centrifugal force) of 28302 g for 30 min at 4 °C. Sonications were carried out using a UD-201 ultrasonic disruptor (Tomy). They typically consisted of 10 repeats of 30 pulses separated by 30 s cooling intervals with an output setting of 4 and a duty setting of 40. The supernatant fraction was heated at 70 °C for 10 min, and insoluble material was removed by repeating the centrifugation step. The sample was applied to a Hi-Trap Q-Sepharose column (GE Healthcatre) equilibrated in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) and was eluted using an increasing NaCl gradient. TRAP eluted at 200–400 mM NaCl. In the case of TRAPsub, the relevant fractions were pooled and further dialysed against 20 mM Mes (pH 6.5) and 100 mM NaCl, applied to a Hi-Trap heparin-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a 0.1–2 M NaCl gradient. TRAP-containing fractions were pooled and dialysed into 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) and 100 mM NaCl and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra spin concentrator (Millipore). Concentrated samples were applied to a Superdex 200 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in the same buffer. Pure TRAP eluted as a single peak. The identity of the protein was confirmed by PAGE analysis and MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight) MS using an Autoflex-YS spectrometer (Bruker).

Removal of tryptophan

Purified TRAP was denatured in 6 M guanidine-HCl and dialysed twice against 400 ml of 6 M guanidine-HCl, followed by four times against 500 ml of 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5), 0.1 M NaCl and 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) in a Slide-A-Lyzer cassette (Pierce Biotech). The entire process was performed twice. The concentration of refolded TRAP was measured at A280 using ϵcoeff=1280 M−1·cm−1 for TRAPsub and 2560 M−1·cm−1 for TRAPste.

Labelled RNA

The 64-base labelled RNA oligomer was designed with a central region containing 11 copies of the consensus sequence ‘NN(N)(G/U)AG’, and conjugated with Dy547 dye at the 5′- end and fluorescein at the 3′- end (Dharmacon). The oligomer was optimized to minimize secondary structural formations. The sequence was as follows: 5′-(Dy547)-AAACCGGAGCAAGAGAUGAGAACGAGUCGAGGGUAGAUGAGAAUGAGCGAGAUUAGAAGAGAAA-(Fl)-3′.

TRAP-RNA binding

In typical experiments, various amounts of TRAP protein were titrated against a set concentration of the labelled RNA, in the presence or absence of L-Trp (L-tryptophan). Each 25 μl reaction contained labelled RNA (0.4 nM and 0.2 nM for the B. subtilis and B. stearothermophilus reactions respectively), a series of 2-fold dilutions of refolded TRAP protein,±0.5 mM L-Trp, and 50 mM Tris/acetate (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT, 4 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 0.004% Bromphenol Blue. The reactions were incubated for 30 min at the appropriate temperature before being subjected to electrophoresis.

Gel electrophoresis and detection

Gels consisted of 10% polyacrylamide in 375 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.8), 5% (v/v) glycerol and 1 mM EDTA. Electrophoresis was carried out at a constant voltage of 200 V for 90 min, in 1×TAE buffer (40 mM Tris base, 20 mM acetic acid and 1mM EDTA). The running temperature of each gel was the same as the temperature used to incubate TRAP and RNA and was controlled by a circulating waterbath. After electrophoresis, the gels were scanned on a Typhoon 8600 imager (GE Healthcare) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm, emission wavelength of 520 nm and PMT (photomultiplier) voltage of 800 V. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Crystallization

B. stearothermophilus apo-TRAP was used at a concentration of 5.3 mg/ml, in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.5) and 50 mM NaCl. Crystals were grown using the hanging drop method at 20 °C in a mother liquor containing 0.1 M Hepes (pH 7.5), 25–28% PEG [poly(ethylene) glycol] 400 and 0.2 M CaCl2. Cubic-like crystals of approx. 150 μm×100 μm×100 μm grew over 1 week.

Data collection and refinement

All crystals were cryo-cooled to −173 °C before collecting data. X-ray diffraction data for apo-TRAP were collected at beamline BL-5A at the Photon Factory, Tsukuba, using radiation of a 1.0 Å wavelength. A total of 160 ° of data were collected in 2.0 ° oscillations. The data were processed to 3.1 Å resolution with HKL2000 [27]. The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 3. Data handling was carried out using the CCP4 suite [28], and molecular replacement was performed with PHASER [29], using tryptophan-liganded TRAPste (PDB code 1QAW), as a search model. Refinement was carried out using CNS [30] and REFMAC [31]. A resolution cut-off of 3.2 Å was applied because of the incomplete and weak data beyond this limit. Thermal displacement parameters (B-factors) were set to 20.0 Å2 for all atoms at the start of refinement. In several solvent-exposed residues with very weak electron densities, the occupancy values for the side-chain atoms were set to 0 or 0.5. NCS restraints were applied to each chain over residues 6–75. Finally, TLS [32] refinement was carried out using two groups, one for each TRAP ring. The R-factor and free R-factor dropped significantly with the addition of TLS parameters. Manual adjustments were made with COOT [33]. The stereochemical properties of the models were checked with PROCHECK [34] and the validation tools of COOT. Residues at the ends of visible pieces of structure tend to move away from the more populated regions of the Ramachandran plot, leading to a higher number than usual in less populated areas, but the central core of the protein refined well. Several surface side chains have atoms whose positions could not be reliably determined by the data, and these atoms were excluded from the model. Figures were created with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger; http://www.pymol.org).

Table 1. Calculated apparent Kd values (nM).

ND, not determined due to excessively weak binding.

| TRAPste | TRAPsub | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | (−) L-Trp | (+) L-Trp | (−) L-Trp | (+) L-Trp |

| 10 | 3.0±0.4 | 1.3±0.2 | 280±30 | 3.8±0.5 |

| 20 | 3.6±0.4 | 2.2±0.3 | ND | 5.3±1.1 |

| 30 | 5.4±0.5 | 1.8±0.3 | ND | 2.8±0.4 |

| 40 | 15±1 | 1.8±0.2 | ND | 30±6 |

| 50 | ND | 1.8±0.3 | ND | 19±2 |

| 60 | ND | 31±3 | ||

RESULTS

TRAP-RNA binding

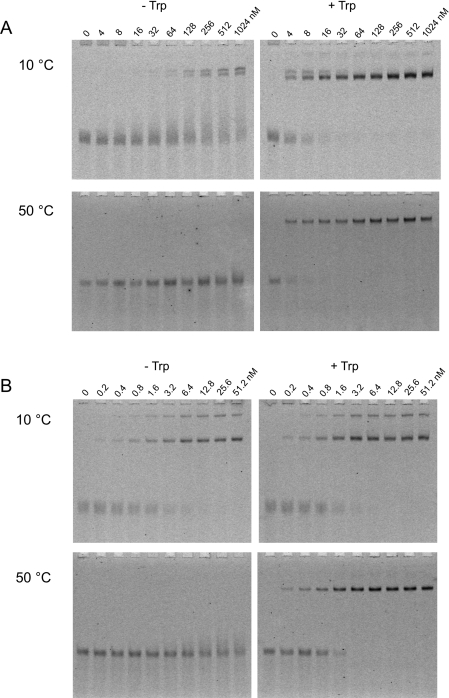

Gel-retardation assays (Figure 2, and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/434/bj4340427add.htm) were performed to assess the effects of temperature on the target RNA-binding ability of TRAPsub and TRAPste. Binding data were fitted to a simple 1:1 binding model (Figure 3 and Table 1). In the presence of ligand, L-Trp, TRAPsub binds to RNA with Kd values from 2.8 to 5.3 nM at temperatures from 10 to 30 °C, and significantly less tightly at temperatures of 40 °C and above. In the absence of L-Trp, zero or negligible binding is observed at 20–60 °C, whereas very weak levels of binding are seen at 10 °C, with an apparent Kd of 280 nM. These results are consistent with previous investigations [36–39].

Figure 2. Gel-retardation experiments showing binding of TRAP to RNA at 10 and 50 °C.

Experiments were carried out with increasing amounts of TRAP (concentrations of the 11-mer TRAP ring are shown above each lane) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of L-Trp. (A) TRAPsub binding to 0.4 nM labelled RNA; (B) TRAPste binding to 0.2 nM labelled RNA. A full set of results can be found in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/434/bj4340427add.htm.

Figure 3. Binding of TRAP to RNA at different temperatures.

The data from EMSA (electrophoretic mobility-shift assays) experiments were fitted to a 1:1 binding equation. The x-axis represents the concentration of the 11-mer TRAP ring, whereas the y-axis denotes the percentage of the fluorescent signal that is shifted. Black, 10 °C; grey, 20 °C; blue, 30 °C; green, 40 °C; orange, 50 °C; and red, 60 °C. (A) TRAPsub without L-Trp; (B) TRAPsub with L-Trp; (C) TRAPste without L-Trp; and (D) TRAPste with L-Trp.

In the case of TRAPste, tight binding to RNA is observed in the presence of L-Trp, with Kd values from 1.3 to 2.2 nM between 10 and 50 °C (Table 1), within the ranges seen previously [40]. A decrease in affinity is observed at 60 °C, with a Kd value of approx. 30 nM. Overall, although the changes are small for temperatures of 50 °C and below, we find a consistent increase in the affinity of RNA for TRAP with decreasing temperature. Previously, decreasing temperature was reported to have either no effect on affinity of RNA for TRAP or to lead to a decrease in affinity, an effect attributed to increasing RNA secondary structure [40]. In the present study, the use of an RNA sequence specifically designed to reduce secondary structure appears to have eliminated this effect. Significantly, high affinity for RNA was also observed in the absence of L-Trp, in a temperature-dependent manner. Between 10 and 30 °C, tryptophan-free TRAPste binds RNA with only slightly lower affinity compared with the tryptophan-bound form, with Kd values in the range of 3.5–4 nM. At 40 °C, however, the apparent Kd increases to approx. 30 nM, and at higher temperatures the binding is too weak to be quantified. At 20 °C, tryptophan-free TRAPste is able to bind to the RNA within a tested salt concentration range of 0–300 mM NaCl, and within a pH range of 6–8 (Supplementary Figure S3 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/434/bj4340427add.htm). Furthermore, the addition of up to 80 μg of non-specific tRNA per binding reaction had no effect on binding at 20 °C (Supplementary Figure S4 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/434/bj4340427add.htm), suggesting that the interaction is highly specific.

A van't Hoff plot of the gel-retardation data (Figure 4 and Table 2) provides a useful qualitative comparison between different proteins. The plot reveals that enthalpy and entropy changes for RNA binding to TRAPste in the absence of tryptophan resemble closely those for TRAPsub in the presence of tryptophan. For TRAPste in the presence of tryptophan, the enthalpy change is minimized and RNA binding appears to be driven by entropy.

Figure 4. Temperature-dependence of RNA binding to TRAP.

A van't Hoff plot constructed from gel-retardation data, plotting the apparent binding constants for TRAPste in the presence (■, fitted with long and short dashed line) and absence (◆, fitted with dashed line) of tryptophan and TRAPsub in the presence of tryptophan (○, fitted with a solid line).

Table 2. Calculated enthalpy and entropy changes of RNA binding to TRAP.

Calculations were carried out based on the results of a van't Hoff plot (Figure 4). ND, not determined due to excessively weak binding.

| TRAPste | TRAPsub | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | (−) L-Trp | (+) L-Trp | (−) L-Trp | (+) L-Trp |

| ΔH (kcal·mol−1) | 4.6 | 0.4 | ND | 4.5 |

| ΔS (cal·mol−1·K−1) | 7.4 | 37.3 | ND | 7.6 |

Apo-TRAP structure

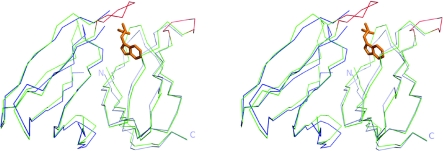

Tryptophan-free TRAPste was crystallized at 20 °C in space group P21. A summary of the data collection and model refinement parameters are shown in Table 3. The asymmetric unit contained two complete TRAP rings, giving a total of 22 individual subunits. The crystal packing showed the TRAP rings arranged in a face-to-face configuration, forming long staggered-tube-like structures. In general, the tertiary structure of the visible regions of the model is very similar to TRAPste bound to tryptophan [15], with the main-chain atoms of the two structures matching with an rmsd of 1.14 Å (Figure 5). However, most of the residues on the BC loop display very weak or no electron density, and have only been modelled in two subunits. As expected, the tryptophan-binding pockets of all subunits were unoccupied. With the exception of the unstructured BC loop, the orientations of the residues lining the tryptophan-binding pocket are essentially unchanged. In contrast, residues on the DE loop which also line the pocket, have clear electron density and display very similar conformations to the tryptophan-bound structure (Figure 6). Interestingly, the residues directly involved in RNA binding (Lys37, Lys56 and Arg58) display weak or ambiguous side-chain electron densities, despite being located away from the tryptophan-binding pocket and the disordered BC-loop region. All of these residues are required for RNA binding. In particular, Lys37 shows weak side-chain electron density in all 22 subunits, and clear side-chain electron density could be observed in only a few subunits for Lys56 and Arg58. In many subunits the occupancies of some side-chain atoms in these residues were set to zero during model refinement.

Table 3. Data collection and refinement statistics for B. stearothermophilus apo-TRAP.

(a) Data collection

| Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21 | |

| Unit cell | a=68.1 Å, b=85.4 Å, c=127.4 Å | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–3.1 | |

| Number of reflections | 84881 | |

| Number of unique reflections | 24780 | |

| Redundancy | 3.4 (2.5)* | |

| Rmerge (%) | 8.2 (24.1)* | |

| Completeness (%) | 94.5 (77.5)* | |

| I/σ (I) | 10.3 (1.4)* | |

| (b) Refinement | ||

| Parameter | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 20.0–3.2 | |

| R-factor (%) | 24.0 | |

| Free R-factor (%) | 26.7 | |

| Average B-factor | 68.0 | |

| Rmsd bond lengths | 0.012 | |

| Rmsd bond angles | 1.321 | |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favoured region (%) | 91.4 | |

| Additionally allowed region (%) | 8.1 | |

*Figures in brackets refer to the outer shell of data, between resolution limits 3.19–3.11 Å.

Figure 5. Stereoview showing an overlay of two adjacent TRAP monomers from apo-TRAPste (blue) and tryptophan-bound TRAPste (PDB code 1QAW, green).

Tryptophan is shown in orange. The BC loop region of tryptophan-bound TRAPste is shown in red. N- and C-termini of one of the apo-TRAP monomers are labelled.

Figure 6. Stereoview showing an overlay of the tryptophan binding site of apo-TRAPste and tryptophan-bound TRAPste.

Amino acid residues are coloured according to element. The amino acid chain and electron-density maps are shown from the apo-TRAP structure only. Tryptophan is shown in orange and is from the tryptophan-bound TRAP structure. The 2Fo−Fc electron-density map is contoured at 1.0 σ. Note the lack of electron density for tryptophan.

DISCUSSION

Models of TRAP function to date have generally accepted that it cannot bind RNA unless it is liganded with tryptophan [19,41–43]. In the present study we have demonstrated that this is not always the case. Gel-retardation experiments show that, as expected, over a wide range of temperatures TRAPsub binds to RNA only in the presence of tryptophan. However, tryptophan-free TRAPste is made able to bind specifically to its cognate RNA simply by lowering the temperature.

The crystal structure of apo-TRAP is similar to that of the tryptophan-bound protein, except that the BC loop and RNA-binding residues show significant disorder. In NMR experiments on apo-TRAP, the BC-loop region as well as the DE loop were found to be disordered [21,22]. In the crystal structure described in the present study, in only two chains (L and O) can the position of the BC loop be defined; however, this seems to be due to crystal contacts with neighbouring molecules. In these chains the loop has undergone a large conformational change compared with the tryptophan-bound structure, moving towards the outside of the ring, demonstrating the flexibility of this region in the absence of tryptophan. In the same L and O chains Thr30 flips to a conformation on the outside of the protein. This is interesting as Thr30 is known to be important for tryptophan binding to TRAP [39] and a hydrogen bond is found between tryptophan and the carbonyl oxygen of Thr30 in tryptophan-bound crystal structures. The position of the flipped Thr30 is incompatible with tight tryptophan binding in the apo-TRAP model described in the present study.

In contrast with the BC loop, residues on the DE loop remain ordered with orientations close to the liganded crystal structure rather than showing the disorder seen in the NMR structure. The discrepancy between the NMR and crystal structures could be due to several factors, such as the difference in temperatures (55 °C compared with −173 °C for the crystal). In addition, the intermolecular contacts within a crystal lattice might themselves lead to the stabilization of loops that would otherwise be disordered in solution [43]. Despite disorder of the RNA-binding residues in the X-ray structure, the apo-protein is still able to bind tightly and specifically to RNA. It appears that this disorder in TRAP is temperature-dependent, although the protein itself is highly thermostable. Apo-TRAP binding to RNA would undermine the stringency of the tryptophan synthesis feedback mechanism. The fact that in the absence of tryptophan TRAPste retains its ability to bind tightly to RNA has been observed before (although the temperature-dependence was not studied), but it was attributed to incomplete removal of tryptophan [41]. However, through unfolding of the protein and extensive dialysis, we have removed all ligand and shown that this binding is an intrinsic property of apo-TRAP.

In previous calorimetry experiments, the ΔS of tryptophan binding to TRAP was found to be zero at approximately 287 K, becoming increasingly negative as the temperature was increased [21]. Enthalpy/entropy compensation was hypothesized to hold the ΔG of binding almost constant over the temperature range studied. This is consistent with the notion that low temperature assists RNA binding by reducing the protein fluctuations. In effect, lowered temperatures seem to mimic the effects of tryptophan ligands on the RNA-binding site. Both TRAPste and TRAPsub can bind RNA in the absence of tryptophan, but much lower temperatures are required in the case of the TRAPsub. TRAPsub therefore requires less thermal energy to destabilize its structure, which is exactly what would be predicted given that B. stearothermophilus is a thermophile whereas B. subtilis is a mesophile. At 20 °C, unliganded TRAPste is sufficiently stabilized to allow ordered crystals to form, but no crystal structure has been determined for apo-TRAPsub. The structural data from X-ray crystallography do not preclude the possibility that at higher temperatures the RNA-binding site may be blocked by other regions of the protein (such as the BC loop), but this seems unlikely since these regions would be highly flexible and not likely to pose a strong barrier to binding. Other smaller changes to the structure and changes to the hydration pattern of the protein may also play roles that we are unable to detect. Furthermore, the binding of RNA to TRAP is known to be co-operative [42], and it may therefore be expected that binding of RNA to a single monomer may be sufficient to stabilize the structure and promote wrapping of the RNA around the protein. We are therefore led to a model in which disorder itself is responsible for the failure of apo-TRAP to bind RNA at normal in vivo temperatures.

The intriguing differences between TRAPste and TRAPsub remain to be explained. While reduced flexibility is strongly implicated in the ability of TRAP to bind RNA at low temperature, enthalpy effects cannot be ruled out. In addition, it is unclear how the presence or absence of tryptophan in the binding pocket is transmitted to the RNA-binding site. Previously we have found that TRAPsub seemed to show negative co-operativity in tryptophan binding, whereas TRAPste showed zero homotropic co-operativity [12]. It was found that position 44 in TRAPsub (isoleucine) plays an important role in communication between tryptophan-binding sites; the equivalent residue from TRAPste (leucine) is more flexible and apparently unable to allow site–site interactions. It is possible that residue 44 may also play a role in heterotropic allostery and the control of RNA binding. Experiments to address this issue are now underway.

In summary, we have carried out extensive RNA-binding experiments using tryptophan-bound and apo-TRAP from B. subtilis and B. stearothermophilus at a range of different temperatures. We find that within their natural temperature range the proteins behave as expected, and bind RNA only when liganded with tryptophan. However, we find that tight, specific RNA binding occurs at low temperatures even when no tryptophan is present. TRAPsub requires much lower temperatures than TRAPste to show this effect.

We have solved the crystal structure of apo-TRAP from B. stearothermophilus and show that the structure is largely similar to that of the tryptophan-bound form, but that a large portion of the BC loop and RNA-binding residues are disordered. Unlike classical models of allostery, there is no switch between different ordered conformational states of the protein. The structure and the RNA-binding data described in the present paper shed new light on the dynamic mechanism of the action of TRAP. In particular, it highlights the important role of vibrational modes in dynamic allostery and suggests that the new crystal structure represents a snapshot of an intermediate dynamic form. Further work is required to understand the different responses to temperature of TRAPste and TRAPsub.

Online data

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Jonathan Heddle and Jeremy Tame designed experiments and wrote the paper; Ali Malay carried out biochemical experiments and wrote the paper; Masahiro Watanabe carried out crystallization and solved the protein crystal structure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Sam-Yong Park for useful discussions.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists [grant number WAKATE B-20710083 (to J.G.H.)]. J.G.H. and A.D.M. were supported by MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology) Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology, awarded to J.G.H.

References

- 1.Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J.-P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koshland D. E., Némethy G., Filmer D. Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotani M. Fluctuation in quarternary structure of proteins and cooperative ligand binding I: generalizations of Monod-Wyman-Changeux model of allosteric enzymes. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 1968;E68:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper A., Dryden D. T. Allostery without conformational change. A plausible model. Eur. Biophys. J. 1984;11:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00276625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui Q., Karplus M. Allostery and cooperativity revisited. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1295–1307. doi: 10.1110/ps.03259908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkins R. J., McLeish T. C. Coupling of global and local vibrational modes in dynamic allostery of proteins. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2055–2062. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tame J. R. H. . Scoring functions: the first 100 years. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2005;19:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s10822-005-8483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai C. J., del Sol A., Nussinov R. Allostery: absence of a change in shape does not imply that allostery is not at play. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frederick K. K., Marlow M. S., Valentine K. G., Wand A. J. Conformational entropy in molecular recognition by proteins. Nature. 2007;448:325–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittermaier A., Kay L. E. New tools provide new insights in NMR studies of protein dynamics. Science. 2006;312:224–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1124964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popovych N., Sun S., Ebright R. H., Kalodimos C. G. Dynamically driven protein allostery. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heddle J. G., Yokoyama T., Yamashita I., Park S.-Y., Tame J. R. H. Rounding up: engineering 12-membered rings from the cyclic 11-mer TRAP. Structure. 2006;14:925–933. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heddle J. G., Okajima T., Scott D. J., Akashi S., Park S. Y., Tame J. R.H. . Dynamic allostery in the ring protein TRAP. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:154–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antson A. A., Otridge J., Brzozowski A. M., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Wilson K. S., Smith T. M., Yang M., Kurecki T., Gollnick P. The structure of trp RNA-binding attenuation protein. Nature. 1995;374:693–700. doi: 10.1038/374693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X., Antson A. A., Yang M., Li P., Baumann C., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Gollnick P. Regulatory features of the trp operon and the crystal structure of the trp RNA-binding attenuation protein from Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:1003–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antson A. A., Dodson E. J., Dodson G., Greaves R. B., Chen X., Gollnick P. Structure of the trp RNA-binding attenuation protein, TRAP, bound to RNA. Nature. 1999;401:235–242. doi: 10.1038/45730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopcroft N. H., Manfredo A., Wendt A. L., Brzozowski A. M., Gollnick P., Antson A. A. The interaction of RNA with TRAP: the role of triplet repeats and separating spacer nucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopcroft N. H., Wendt A. L., Gollnick P., Antson A. A. Specificity of TRAP–RNA interactions: crystal structures of two complexes with different RNA sequences. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:615–621. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gollnick P., Babitzke P., Antson A., Yanofsky C. Complexity in regulation of tryptophan biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:47–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.093745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe M., Heddle J. G., Kikuchi K., Unzai S., Akashi S., Park S. Y., Tame J. R. H. . The nature of the TRAP-Anti-TRAP complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2176–2181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801032106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McElroy C. A., Manfredo A., Gollnick P., Foster M. P. Thermodynamics of tryptophan-mediated activation of the trp RNA-binding attenuation protein. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7844–7853. doi: 10.1021/bi0526074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McElroy C., Manfredo A., Wendt A., Gollnick P., Foster M. TROSY-NMR studies of the 91kDa TRAP protein reveal allosteric control of a gene regulatory protein by ligand-altered flexibility. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;323:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murtola T., Vattulainen I., Falck E. Insights into activation and RNA binding of trp RNA-binding attenuation protein (TRAP) through all-atom simulations. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2008;71:1995–2011. doi: 10.1002/prot.21878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heddle J. G., Fujiwara I., Yamadaki H., Yoshii S., Nishio K., Addy C., Yamashita I., Tame J. R. H. Using the ring-shaped protein TRAP to capture and confine gold nanodots on a surface. Small. 2007;3:1950–1956. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe M., Mishima Y., Yamashita I., Park S.-Y., Tame J. R. H., Heddle J. G. Intersubunit linker length as a modifier of protein stability: crystal structures and thermostability of mutant TRAP. Protein Sci. 2008;17:518–526. doi: 10.1110/ps.073059308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda F. F., Iwasaki K., Akashi S., Sumitomo K., Kobayashi M., Yamashita I., Tame J. R. H., Heddle J. G. A self-assembled protein nanotube with high aspect ratio. Small. 2009;5:2077–2084. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. In: Carter C. W. Jr, editor. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Collaborative Computational Project 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., et al. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schomaker V., Trueblood K. N. On the rigid-body motion of molecules in crystals. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 1968;B24:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reference deleted.

- 36.Barbolina M. V., Kristoforov R., Manfredo A., Chen Y., Gollnick P. The rate of TRAP binding to RNA is crucial for transcription attenuation control of the B. subtilis trp operon. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;370:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumann C., Otridge J., Gollnick P. Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of the interaction between TRAP (trp RNA-binding attenuation protein) of Bacillus subtilis and trp leader RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12269–12274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li P. T., Scott D. J., Gollnick P. Creating hetero-11-mers composed of wild-type and mutant subunits to study RNA binding to TRAP. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11838–11844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yakhnin A. V., Trimble J. J., Chiaro C. R., Babitzke P. Effects of mutations in the L-tryptophan binding pocket of the Trp RNA-binding attenuation protein of Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4519–4524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elliott M. B., Gottlieb P. A., Gollnick P. Probing the TRAP–RNA interaction with nucleoside analogs. RNA. 1999;5:1277–1289. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Babitzke P. Regulation of tryptophan biosynthesis: Trp-ing the TRAP or how Bacillus subtilis reinvented the wheel. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;26:1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5541915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babitzke P. Regulation of transcription attenuation and translation initiation by allosteric control of an RNA-binding protein: the Bacillus subtilis TRAP protein. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gollnick P. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis trp operon by an RNA-binding protein. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;11:991–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.