You know institutions tend to become static; they build walls around themselves to protect themselves from change, and eventually die. You should fight that by opening up your thinking and your ideas, and work for a change.

—Sidney Garfield, MD1

Introduction

As early as 1960, Sidney Garfield, MD, the co-founder of Kaiser Permanente (KP), foresaw how computers would become powerful tools to help patients.2 It is in his maverick spirit that we examine the potential for social media to be powerful tools to help our patients today.

Social media, or content created and exchanged within virtual communities through the use of online tools, are used by millions of people to converse and to connect.3 Health systems can use social media to engage members and potential members by building trust and making large organizations more accessible and approachable.4 Social media can help patients manage their chronic conditions and make healthy choices; it also can accelerate knowledge acquisition and dissemination for patients and clinicians.

Health and health care organizations are popular topics in social media conversations, and both positive and negative stories shared through online networks can have an enormous reach. KP experienced this in 2006, after unfavorable media coverage of the KP HealthConnect electronic health record system emerged on social media sites.5 Positive messages can also spread as has been the case of the KP Thrive advertisement “When I Grow Up,” which was hosted on the social network video site YouTube. The video portrayed images of active women seniors alongside a message promoting mammography that attracted more than 125,000 views garnering significant attention from repeat viewers and women in the target demographic of 55 and older.

Although there are risks for health systems to participate in social media, there are also risks in not participating. In a patient-centered model of health care, absence from social networks that are important to patients might lead to a gap between patients and clinicians. In this article, we will focus on the promise of social networking and review potential risks of both participation and abstention.

Social Networking and Social Media

Social networking is not a program or a Web site; it is a community of people who share similar interests and activities who interact through online and mobile technologies. Facebook, Twitter, and blogs are Web platforms used to connect people and transform the publishing of media from broadcast media monologues into social media dialogues.3 The rapid and extensive penetration into society of these sites is related to their ability to facilitate talking as well as listening, consuming as well as participating. Whereas it took nearly 40 years for computers to become mainstream, it took Facebook less than 6 months to add 100 million people.6 Today more than 500 million people use Facebook regularly.7 Among adults in the US, 42% use social networking sites. Among young adults (age 18–29 years), the figure is an impressive 86%.8

Building Trust and Understanding

Because of the “no advertising rule” in the American Medical Association's code of ethics, which existed from 1847 to 1975, health care organizations were barred from communication that could subject physicians to allegations of “soliciting” patients. In the post-“no advertising rule” era, however, health care organizations have begun to adopt best practices of the public relations and issues management field. One key concept is the “bank of good will.” Good news generated by an organization strengthens its reputation in the marketplace and among policymakers and influencers. Good news also protects against potentially harmful messages. When this bank is depleted because of the absence of positive mentions, organizations face reduced effectiveness as the result of a damaged reputation. Adding to this understanding, large media outlets and organizations no longer generate all news and messaging. In today's world of democratized influence, consumers generate news. A 2010 report by the Pew Internet and American Life Project9 confirms this reality: 37% of Internet users have actively contributed to the creation, commentary, or dissemination of news. In addition, 75% of online news consumers get news forwarded through e-mail or posts on social networking sites.

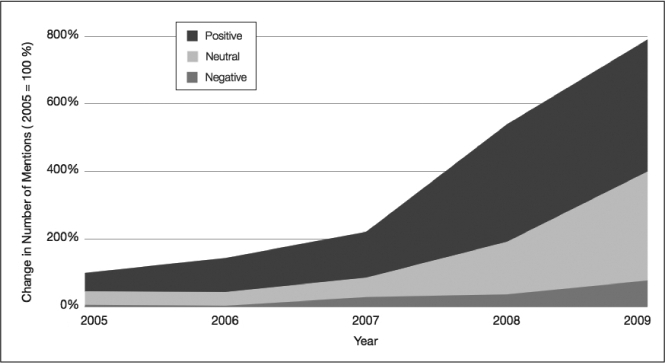

In practice, a successful organization tracks positive, neutral, and negative media “mentions.”

Data show that KP has internalized the bank of good will best practice.

Figure 1 demonstrates the visible change in media mentions (defined as a reference to the organization in print publications, television, and the Internet) from KP's work.

Figure 1.

Media mentions: Kaiser Permanente 2005–2009

37% of Internet users have actively contributed to the creation, commentary, or dissemination of news.

Twitter and other social media exert leverage by using positive network effects. This means that one message reaches the direct followers, who then share the original message in an exponential fashion, increasing the value of the network to the individuals who participate in it. The positive network effect provides fast and free distribution of messages to health consumers. A recent demonstration of this effect occurred with the media release of KP's electronic health record collaboration with the Department of Veterans Affairs in January 2010.10 Through the use of social networking tools such as Twitter, an audience of hundreds was expanded to an audience of over 75,000 within 48 hours, with 92% of the reach created by individuals not affiliated with KP.11

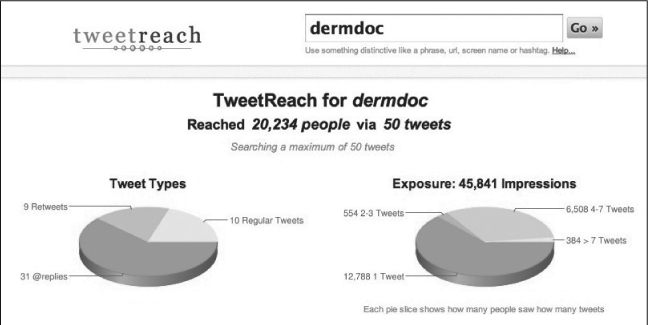

An example that examines the reach of just one physician demonstrates the potential of building the bank of good will.

In Figure 2, the content generated by a single KP physician, in this case coauthor Jeffrey Benabio, MD, a dermatologist, (“Tweet Type” pie chart), is compared to the reach of each piece of content, copied and forwarded, and tracked through the Internet.

Figure 2.

TweetReach's Twitter statistics page for Jeffrey Benabio, MD.

Following on this analogy, each impression equals a deposit to a bank of good will. The conservative approach to social media participation has typically been to use social media “handles” and profiles that avoid mention of organizational affiliation, as is the case above. The significant impact of positive mentions and the dominance of user-generated content in media mentions has changed this view, however, turning what was once thought of as a liability into an asset in the positioning of a care system as the model for the future. If the physician instead is identified as part of a Medical Group in their social media handle or profile, the deposit of good will goes to the organizational “account” in addition to the individual “account.” Combined with the network effect of multiple physicians participating, their impact in support of the health system's efforts to support patient, family, and community health is multiplied exponentially.

Knowledge Dissemination

Studies of the impact and accuracy of health information disseminated via social networks are only beginning to be published.12 Statistics clearly demonstrate a demand for social media in medicine, which provides an opportunity for clinicians and health care organizations to engage their patients. During the H1N1 outbreak of 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) turned to social networking site Twitter to communicate with clinicians across the US. The CDC employs a Twitter feed for emergency information (more than 1.2 million followers) and also for flu information (46,000 followers).13 There are numerous examples of individual physicians using social media to educate and support patients in preventing and managing chronic illness. Additionally, we are seeing a growing effort within the health sector to embrace social media as evidenced by the creation of the Mayo Clinic Center for Social Media. Physicians involved in these efforts cite the use of social media as the enabler of societal purpose in their professional work, whether it is to “realign families with science”14 or “tap into the reason we all went into medical school, to make a difference in people's lives.”15

Mitigating Risks

A recent legal review of social media concluded, unsurprisingly, that “in the health care context, complex situations can arise.”16 For example, a physician unaccustomed to mass communication might be misquoted or contribute to negative perceptions of his or her practice or health system, intentionally or not. In addition, a broader perspective of risk must include the actions of physicians, staff, patients and their families. Employees have been terminated for tweets that violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); discovered Facebook and MySpace conversations have led to insurance coverage litigation; civil complaints have been filed alleging libel/defamation of clinicians in the use of online rating sites.16 The protection of patient privacy is paramount and requires special attention. Multiplying the number of communicators and the number of environments can increase the risk of harm to those we serve and of harm to the organization's integrity and ability to carry out its mission. Paul Levy, former CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, points out in his social media work that “any form of communication (even conversations in the elevator!) can violate important privacy rules.”16p13 For this reason, an approach to social media that is applicable across all forms of communication is fitting.

An organizational social media policy is a first step in acknowledging employee activity and managing risks, “to keep them and your company safe as well as responsive.”17 KP's social media policy,18 ratified in 2009 has been freely available for organizations to learn from and is considered a model in the health care industry.19 Greater actualization of benefits, including maintaining and growing a bank of good will, requires a transition in thinking from prohibiting all social media activity to active, guided engagement of all who wish to participate.20

Conclusion

Although health care's understanding of the potential of social media is still in its infancy, more innovation is inevitable. Health care organizations and individual physicians are already using social media regularly to build trust, promote management of health and wellness, and disseminate knowledge. For health care systems and physician groups with a tradition of innovation and responsible growth, organized social media participation can extend the benefits of excellent communication with patients and potential consumers to enhance their relationship with us and promote achievement of their life goals through optimal health.

In an August 2010 conversation with the author (TE), Jack Cochran, MD, Executive Director of The Permanente Federation, the national umbrella organization for KP's 15,000 physicians, stated: Today's health system leaders are beginning to appreciate social media as “another societal asset that we need to be conversant in, and imagine how it will all link to a better future, instead of imagining that it will go away.” Leadership in the use of social media is an opportunity and a challenge for a health system to engage with a changing stakeholder group. On the basis of current life expectancy, it is possible that an individual over the age of 50 today could be cared for by a physician who is not yet born, and both these physicians and their patients will have different expectations for interaction than exist today.

“Social media is already integral to how people now live their lives and, increasingly, it plays an important role in how they manage their health,” says Holly Potter, Vice President of Public Relations at Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. “If we want to be relevant partners, helping our members and their families manage their health, it is our obligation to learn how to engage—safely, respectfully, and authentically.”

A sustained educational effort will be required to address gaps in understanding, manage fears, and mitigate tangible risks. We see the enormous potential of these tools to help a care system fulfill its purpose. At the same time, we are mindful of the benefits of learning from and teaching colleagues about this significant change in the way we will interact, with encouragement from medical leaders:

“Social media is formidable, very real. It's all around us and gaining momentum. We need to become savvy enough to help direct our colleagues to understand its potential, negative and positive.” Dr Cochran related to the author (TE) in their August 2010 conversation.

It may be normal one day for every physician and nurse to maintain a social media presence as health professionals committed to the health of individuals and populations. We are hopeful that this article will continue conversations already started about this future and the way we will shape it, in the interest of moving ahead together for the benefit of those we serve.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Debley T. The story of Dr Sidney R Garfield: the visionary who turned sick care into health care. Oakland, CA: The Permanente Press; 2009. p. 119. p. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield S. The delivery of medical care. Sci Am. 1970 Apr;222(4):15–23. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0470-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social media [monograph on the Internet] San Francisco, CA: Wikipedia; 2010. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media. [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the role of the Internet in the lives of consumers [monograph on the Internet] St Louis, MO: Fleishman-Hillard; New York: Harris Interactive: Digital Influence Index; 2010 Jun. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: http://digitalinfluence.fleishmanhillard.com/ [Google Scholar]

- TECH/HEALTH PLANS. A Permanente Group executive speaks [monograph on the Internet] San Francisco, CA: The Health Care Blog; 2006 Nov 13. [cited 2010 Dec 4]. Available from: www.thehealthcareblog.com/the_health_care_blog/2006/11/tech-health_plan_1.html. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Facebook crosses 250 million user mark, adds 100 million new users in 6 months [monograph on the Internet] Palo Alto, CA: Inside Network; 2009 Jul 15. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: www.inside-facebook.com/2009/07/15/facebook-crosses-250-million-user-mark-adds-100million-new-users-in-6-months/ [Google Scholar]

- Press room: Facebook factsheet. Palo Alto, CA: facebook; 2011. [cited 2011 Jan 4]. Available from: www.facebook.com/press/info.php?statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Madden M. Older adults and social media [monograph on the Internet] Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2010 Aug 27. [cited 2010 Sep 3]. Available from: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Older-Adults-and-Social-Media.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell K., Rainie L, Mitchell A, Rosenstiel T, Olmstead K. Understanding the participatory news consumer [monograph on the Internet] Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2010 May 1. [cited 2010 Sep 3]. Available from: http://pewinternet.com/Reports/2010/Online-News.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty T, Kahn R, Roberts K. Veterans Affairs and Kaiser Permanente share electronic health information to improve care for veterans [press release on the Internet] Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente News Center; 2010 Jan 6. [cited 2010 Aug 26]. Available from: http://xnet.kp.org/newscenter/pressreleases/net/2010/010610vamedexchangepilot.html. [Google Scholar]

- TweetReach for va, Kaiser Permanente [data on the Internet] San Francisco, CA: Appozite; 2011. [cited 2011 Jan 8]. Available from: http://tweetreach.com/reach?q=va%2C+kaiser+permanente. [Google Scholar]

- Scanfield D, Scanfield V, Larson EL. Dissemination of health information through social networks: Twitter and antibiotics. Am J Infect Control. 2010 Apr;38(3):182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDCemergency: Twitter profile [Web page on the Internet] San Francisco, CA: Twitter; 2011. [cited 2011 Jan 4]. Available from: http://twitter.com/CDCEMERGENCY. [Google Scholar]

- Eytan T. “The more we change the world”—Blog-ter-view with Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, about physicians and social media [blog on the Internet] Washington, DC: Ted Eytan, MD; 2010 Aug 8. [cited 2011 Jan 10]. Available from: www.tedeytan.com/2010/08/10/6078. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. The doctor will see you now?? Comment by Sara Stein, MD [blog on the Internet] Knoxville, TN: Pershing, Yoakley and Associates; 2010 Aug 13. [cited 2011 Jan 10]. Available from: http://healthcareblog.pyapc.com/2010/08/articles/healthcare-reform/technology-social-media/the-doctor-will-see-you-now/ [Google Scholar]

- Coffield RL, Joiner JE. Risky business: Treating tweeting the symptoms of social media. AHLA Connections. 2010 Mar;14(3):10–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bernoff J, Schadler T. Empowered. The Harvard Business Review. 2010 Jul–Aug:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Permanente social media policy [monograph on the Internet] Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente; 2009 Apr 30. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: http://xnet.kp.org/newscenter/media/downloads/social-mediapolicy_091609.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Li C. Open leadership: how social technology can transform the way you lead. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010. p. 336. p. [Google Scholar]

- Owyang J. Breakdown: The five ways companies let employees participate in the social web [monograph on the Internet] San Francisco, CA: Web Strategy; 2009 Jul 15. [cited 2010 Aug 3]. Available from: www.web-strategist.com/blog/2009/07/15/three-ways-companies-let-employees-participate-in-the-social-web. [Google Scholar]