Abstract

We tested the role of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in the homologous recombination process. A tissue-culture based homology-directed repair assay was used in which repair of a double-stranded break by homologous recombination results in gene conversion of an inactive GFP allele to an active GFP gene. Our rationale was that hyperacetylation caused by HDAC inhibitor treatment would increase chromatin accessibility to repair factors, thereby increasing homologous recombination. Contrary to expectation, treatment of cells with the inhibitors significantly reduced homologous recombination activity. Using RNA interference to deplete each HDAC, we found that depletion of either HDAC9 or HDAC10 specifically inhibited homologous recombination. By assaying for sensitivity of cells to the interstrand cross-linker mitomycin C, we found that treatment of cells with HDAC inhibitors or depletion of HDAC9 or HDAC10 resulted in increased sensitivity to mitomycin C. Our data reveal an unanticipated function of HDAC9 and HDAC10 in the homologous recombination process.

Keywords: Chromatin, DNA Damage, DNA Recombination, DNA Repair, Histone Deacetylase

Introduction

Acetylation of lysine residues on histones in chromatin is a key, reversible modification and is regulated by two classes of enzymes: histone acetyl transferases (HATs)2 and histone deacetylases (HDACs). It has been shown that hyperacetylation of histones, driven by HATs (1), causes open chromatin structure, thereby stimulating transcription (2–4). On the other hand, HDACs catalyze histone hypoacetylation and subsequent chromatin compaction that is transcriptionally repressive (5, 6). This form of epigenetic management controls multiple processes such as transcription, cell proliferation and differentiation, cell cycle progression, and angiogenesis (7, 8).

Although epigenetic regulation is important for normal cell function, epigenetic deregulation is detected in some cancers (9, 10). Aberrant expression of some HATS and HDACs has been observed in some cancers (11). As examples, HDAC2 and HDAC3 are overexpressed in gastrointestinal tumors (12, 13).

A group of cytostatic agents called HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) has attracted significant research interest (14). A variety of HDACi, including sodium butyrate (NaB), valproic acid (VPA), trichostatin A (TSA), and apicidin have been found to reverse the transformed state of cancer cells and inhibit the growth of a variety of tumor types, although little is known about the biological function of individual HDACs (15–23).

In this study, we find that HDAC9 and HDAC10 activity is required in HeLa cells for homology-directed repair of DNA double strand breaks. This result was surprising because we had anticipated that HDAC activity would compress chromatin and impede the repair process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Plasmids, Antibodies, and Reagents

The HeLa-DR-13-9 (HeLa-DR) cells have been described before (24, 25), and the standard culturing methods were used. The HDAC inhibitors were procured as follows: TSA, apicidin, valproic acid (2-propylpentanoic acid), and NaB were from Sigma-Aldrich. The siRNA sequences for the HDACs are listed in supplemental Table S1. The HDAC9 antibody has been described previously (26).

Homology-directed Repair Assay

On day 1, we plated HeLa-DR cells (∼2 × 105 in a 10-cm2 well). The next day, the 50% confluent wells were transfected with 3 μg of pCBASceI plasmid while simultaneously adding the HDAC inhibitors. Lipofectamine 2000 was used as the transfection agent, and Opti-MEM was used as the dilution medium. The inhibitors were added to obtain the following final concentrations: TSA (300 nm), apicidin (10 μm), valproic acid (2 mm), and NaB (10 mm). The transfection medium was replaced 6 h after transfection, and the inhibitors were added again for a total of 24 h. On day 5 (96 h after transfection), the cells were trypsinized, and those among 10,000 total cells that expressed green fluorescence were measured using a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur instrument in the Ohio State Comprehensive Cancer Center Analytical Flow Cytometry core laboratory. For the experiment with HDAC depletion by RNA interference, we performed two rounds of transfection. On day 1, we plated HeLa-DR cells (4 × 104 in a 2-cm2 well). On day 2, we performed the first transfection with 60 pmol of siRNA with 1.5 μl of Oligofectamine. On day 3, the cells were transferred to 10-cm2-well dishes. On day 4, we co-transfected 100 pmol of siRNA with 3 μg of pCBASCeI expression vector. On day 7, the cells were analyzed by FACs as above.

Mitomycin C Assay

For the assay with HDAC inhibitors, the cells were pretreated with the inhibitors at the following final concentrations: TSA (300 nm), apicidin (10 μm), VPA (2 mm), and NaB (10 mm) for a total of 24 h. A total of 2000 cells were plated in triplicate per treatment and subjected to 0, 50, and 100 ng of mitomycin C each for 4 h. Medium was then replaced, and cells were allowed to proliferate into colonies for 2 weeks. At the end of that period, the colonies were stained with 0.01% crystal violet solution and then counted.

Cell Cycle Assay

HeLa-DR cells were pretreated with the inhibitors at the following final concentrations: TSA (300 nm), apicidin (10 μm), VPA (2 mm), and NaB (10 mm), or cells were depleted of HDAC9 or HDAC10 by RNAi. At time intervals of 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, cells were harvested and fixed with 70% chilled ethanol for 1 h. Cells were treated with RNase A (0.1 mg/ml) and stained with propidium iodide (0.1 mg/ml) for 1 h. Cell cycle distribution was then measured by FACs, which measures DNA content.

Statistical Analyses

Comparison of each treatment with control was tested by applying a pairwise t test. Linear trend analysis across the dose level was performed by applying a linear model. For the mitomycin C (MMC) assay, at the 50 and 100 ng/ml dose levels, comparison of each treatment with control was tested by applying a pairwise t test. All the data were log 2-transformed before applying t tests.

RESULTS

We began this study by searching for genes with expression levels in microarray results that would reflect coordinate regulation with BRCA1, BRCA2, and BARD1 (BRCA1-associated RING domain protein 1) (27). We found that many HDACs were among those genes co-regulated in microarray datasets with these three genes important in breast cancer and in DNA double strand break repair (data not shown). We tested the role of HDACs in HDR in a tissue culture-based assay and were surprised to find that one or more HDACs were required for the homologous recombination process.

Treatment with HDACi Inhibits Homologous Recombination

We have cloned a HeLa-derived cell line (25) that includes the homologous recombination substrate previously developed (24, 28). The cell line, called HeLa-DR (25), contains in its genome two inactive alleles of GFP. One of the alleles has an 18-bp I-SceI restriction endonuclease site. Expression in these cells of the I-SceI endonuclease results in a single double strand break in one inactive GFP allele, and homologous recombination using sequences in the second allele will result in gene conversion to produce a functional GFP gene. Homologous recombination events are readily scored by flow cytometry of cells.

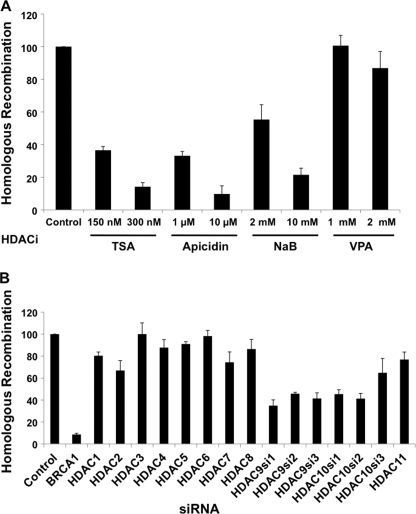

We tested the HDAC inhibitors TSA, apicidin, VPA, and NaB. We anticipated that these chemicals would result in hyperacetylation and opening of the chromatin facilitating the repair. To test this, we transfected the endonuclease I-SceI-expressing plasmid in the presence of the HDACi, and 6 h later, we washed out the transfection mix and added back the HDACi for another 18 h. Cells were incubated in the absence of HDACi for an additional 2 days. Contrary to our expectation, we found that treatment of cells with three of these HDACi compounds resulted in potent inhibition of homologous recombination. With the exception of VPA, significant decreases in levels of homologous recombination were detected on treatment with the inhibitors (Fig. 1A). This inhibitory effect of the HDACi was independent of BRCA1 depletion (data not shown). The inhibition of HDR by the HDACi was dosage-dependent and was up to 11-fold decreased in homologous recombination activity. This level of decrease in the HDR assay was comparable with the loss of activity observed after depletion of BRCA1 by RNAi (Fig. 1B). This result clearly shows that HDACs may play a role in homologous recombination and inhibiting them consequently blocks homology-directed repair. It was striking that VPA was not effective in inhibiting homologous recombination, whereas the other three HDACi tested were. The VPA was effective in other assays because treatment of cells with VPA did result in hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 as detected by immunoblotting and by Triton acid urea gel electrophoresis of purified histones (data not shown). We inferred from this specificity of different HDACi in inhibiting the HDR assay that a subset of the different HDACs regulated this process.

FIGURE 1.

HDAC9 and HDAC10 are required for the homologous recombination process. A, HDR assay with HeLa-DR cells treated with the following final concentrations of HDACi: TSA (150 and 300 nm); apicidin (1 and 10 μm); VPA (1 and 2 mm); NaB (2 and 10 mm). The measure of the cells fluorescing green in the control sample was normalized to 100, and results obtained for the HDACi-treated samples were calculated relative to the normalized control (± S.E.). A paired t test was done in which each of the treatments was compared with the control, and statistically significant results were: TSA (p = 0.0001), apicidin (p = 0.03), and NaB (p = 0.003). B, HDR assay was performed with transfected control siRNA or siRNAs specific for each HDAC, from HDAC1 through HDAC11. The percentage of GFP-positive cells in the control transfected sample was normalized to 100, and the measures for rest of the samples were calculated relative to the control (± S.E.). By comparing the HDAC-depleted results with the control results using a paired t test, the following results were found to be statistically significant: HDAC1 (p = 0.01); HDAC2 (p = 0.04); HDAC9 siRNA-1 (HDAC9si1) (p = 0.008); HDAC9 siRNA-2 (HDAC9si2) (p = 0.00009); HDAC9 siRNA-3 (HDAC9si3) (p = 0.005); HDAC10 si1 (p = 0.007); and HDAC10 siRNA-2 (HDAC10si2) (p = 0.003).

Depletion of Either HDAC9 or HDAC10 Inhibits Homologous Recombination

The next step was to determine which of the HDACs were required for homologous recombination activity. The HDAC inhibitors used broadly inhibit Class I, II, and IV HDACs (28). These classes include HDACs 1 through 11 but do not include the sirtuins (29). Thus, HDACs 1 through 11 were each depleted by RNA interference. The siRNAs for each of these HDACs were culled from the literature, and the sequences and references are listed in supplemental Table S1. The HDACs most commonly associated with transcriptional corepressor complexes, HDAC1 and HDAC2 (30), had a modest inhibitory effect on homologous recombination (Fig. 1B). Depletion of HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC8, and HDAC11 had no significant effect on homologous recombination activity. Of all the HDACs, depletion of HDAC9 and HDAC10 significantly decreased homologous recombination (Fig. 1B). On noting an initial effect, we tested three siRNAs each for HDAC9 and HDAC10. HDAC9 depletion had the stronger effect, with siRNA-1 decreasing homology-directed repair almost 3-fold and HDAC10 siRNA-2 having a 2.5-fold effect. Because we used three siRNAs targeting distinct sequences for each HDAC9 and HDAC10 and all of these resulted in significantly decreased homologous recombination activity, the inhibition is unlikely to be due to any off-target effects of the siRNA.

We tested for depletion of the HDAC proteins by immunoblot analysis. In those cases in which the commercial antibody did not stain a specific band on immunoblot analysis, we quantified the HDAC mRNA by RT-PCR (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). We detected decreased HDAC protein or mRNA abundance in each case. In some cases, the depletion in the HDAC was modest, and this included both HDAC9 and HDAC10, both of which had the largest effect on the HDR assay. Because the level of protein or mRNA depletion was not complete in each case, we posit that the inhibition of the HDR assay by the HDACi compounds was more complete and thus inhibited the process more than 10-fold, but the siRNA treatment yielded more modest effects.

We also tested whether simultaneous depletion of HDAC9 and HDAC10, or a variety of simultaneous depletions, would additively inhibit homologous recombination. However, in each case, there was no change in the levels of homologous recombination (data not shown).

HDACi Treatment or Depletion of Either HDAC9 or HDAC10 Sensitizes Cells to Mitomycin C

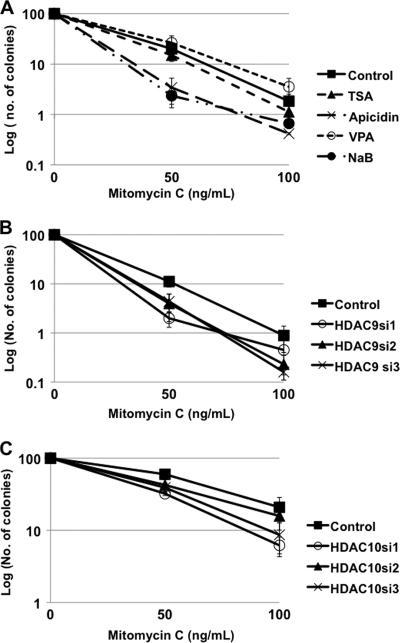

To corroborate the results from the HDR assay, we tested whether inhibition of HDACs or depletion of HDAC9 or HDAC10 decreased the resistance of cells to the interstrand cross-linker, MMC. Sensitivity to MMC often correlates with inhibition of the HDR assay (31, 32). We performed a clonogenic assay upon treatment of HeLa-DR cells with the HDAC inhibitors. Pretreatment with the HDAC inhibitors, apicidin and NaB, significantly sensitized cells as compared with the control. Although TSA strongly inhibited the HDR assay, its effect on sensitizing cells to MMC was modest and not statistically significant. VPA had no effect, and this was consistent with the results obtained in the HDR assay (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

HDAC9 depletion sensitizes cells to mitomycin C. A, clonogenic survival on exposure to MMC was assessed on treatment of HeLa-DR cells with the HDAC inhibitors: TSA (300 nm); apicidin (10 μm); VPA (2 mm); and NaB (10 mm). The cells were pretreated with the HDACi for a period of 24 h before plating 2000 cells/dish and then adding MMC in doses of 0, 50, and 100 ng/ml for 4 h. Cells were then cultured in the absence of HDACi and without MMC for 2 weeks, and surviving colonies were stained and counted. The colony count was normalized to 100 for the 0 ng/ml sample within each treatment, including control (± S.E.). Results were analyzed using a paired t test for each treatment using the 0 ng of MMC value as the control. Statistically significant differences from the control were observed with apicidin (50 ng/ml, p = 0.09; and 100 ng/ml, p = 0.06) and with NaB (50 ng/ml, p = 0.009; and 100 ng/ml, p = 0.03). B, the same clonogenic assay as in panel A was repeated but with HDAC9 depletion. The transfections to deplete HDAC9 were performed as for the HDR assay, and sensitivity to MMC was assayed 48 h after the second transfection. Colony counts were normalized to 100 using the 0 ng/ml MMC results and shown (± S.E.). Using the paired t test, comparing the HDAC9 siRNA with the control siRNA, it was found that HDAC9 siRNA-1 (HDAC9si1) significantly sensitized cells to 50 ng/ml MMC (p = 0.01). HDAC9si2, HDAC9 siRNA-2; HDAC9si3, HDAC9 siRNA-3. C, the same clonogenic assay as in panel A was repeated but with HDAC10 depletion. The transfections to deplete HDAC10 were performed as for the HDR assay, and sensitivity to MMC was assayed 48 h after the second transfection. Colony counts were normalized to 100 using the 0 ng/ml MMC results and shown (± S.E.). Using the paired t test, comparing the HDAC10 siRNA with the control siRNA, it was found that HDAC10 siRNA-1 and siRNA-2 (HDAC10si1 and HDAC10si2) significantly sensitized cells to 50 ng/ml MMC (p = 0.008 and p = 0.04, respectively). HDAC10si3, HDAC10 siRNA-3.

We tested depletion of HDAC9 and HDAC10 on resistance to MMC. After two rounds of siRNA transfections targeting HDAC9 or HDAC10, cells were plated, and MMC was added to the cells for 4 h. As compared with the control siRNA transfection, HDAC9-depleted and also HDAC10-depleted cells were more sensitive to MMC as seen by decreased colony survival. Similar effects on cell survival were seen with all three different siRNAs for both HDAC9 and HDAC10 (Fig. 2, B and C). In each case, the S.E. did not overlap with the control sample, although when applying the pairwise t test, only the results from HDAC9 siRNA-1 at 50 ng/ml MMC were significant. For HDAC10, the results from HDAC10 siRNA-1 and siRNA-3 were significant at 50 ng/ml MMC. As with the HDR assay, the effects of the apicidin and NaB had greater magnitude than did the depletion of the HDAC9 or HDAC10, but the results were consistent.

Effect of HDAC Inhibition on Homologous Recombination Is Not Due to Cell Cycle Perturbation

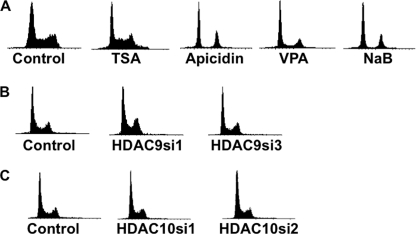

It has been shown in some studies that HDAC inhibitors block the cell cycle in different phases (33). Therefore, we tested whether the effect of the inhibitors and HDAC9 or HDAC10 depletion on homology-directed repair is indirect via a cell cycle block. We treated HeLa-DR cells with the HDAC inhibitors TSA (300 nm), apicidin (10 μm), VPA (2 mm), and NaB (10 mm) for varying intervals of time: 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. At each of these time points, cells were collected, fixed, and then stained with propidium iodide. We note that the 24-h time point correlates with the time at which the HDR assay was done. Flow cytometry results revealed that TSA- and VPA-treated cells had a normal cell cycle progression at all time intervals as compared with control cells. Fig. 3A shows the results from 24 h of HDACi treatment. Apicidin- and NaB-treated cells, at 24 h, had a decrease in S-phase cells as evidenced by a decrease in the numbers of cells with DNA content between the 2n (unreplicated DNA) and 4n (fully replicated DNA) peaks. Because the TSA treatment did not affect the cell cycle but did inhibit the HDR assay, then its effect on the homologous recombination process is not secondary to a cell cycle block.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of HDAC9 and HDAC10 depletion on cell cycle progression. Histogram plots are depicted showing cell cycle progression for the following treatments. A, HeLa-DR cells were pretreated with the inhibitors at the following final concentrations: TSA (300 nm), apicidin (10 μm), VPA (2 mm), and NaB (10 mm) and harvested at 24 h. B, HDAC9-depleted HeLa cells were analyzed for effects on the cell cycle. HDAC9si1, HDAC9 siRNA-1; HDAC9si3, HDAC9 siRNA-3. C, cells depleted of HDAC10 were analyzed for effects on the cell cycle. HDAC10si1, HDAC10 siRNA-1; HDAC10si2, HDAC10 siRNA-2. Quantitation of the percentage of cells in each stage of the cell cycle is shown in supplemental Fig. S4.

Whether HDAC9 or HDAC10 depletion impacted progression through the cell cycle was tested. Using the same timing as used in the HDR assay, siRNAs specific to HDAC9 and HDAC10 were transfected into HeLa-DR cells; after 48 h, the transfection was repeated, and at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the second transfection, cells were collected for cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry. HDAC9 as well as HDAC10 depletion had no discernible effect on cell cycle progression at 24 h after transfection (Fig. 3, B and C) and at 48, 72, and 96 h (data not shown). Therefore, the effect of HDAC9 and HDAC10 depletions on the double strand break repair process is not attributed to a cell cycle block but to a direct activity required for the repair process.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have established a role for HDAC9 and HDAC10 in the homologous recombination process. We used a tissue culture-based homology-directed repair assay in which repair of a specific double-stranded break by homologous recombination converts an inactive GFP allele to active GFP. Contrary to our expectation, three of the HDACi reduced homologous recombination levels significantly.

Next, we found that only HDAC9 and HDAC10 depletions resulted in a large defect in homologous recombination activity. This effect was observed with multiple siRNAs for each HDAC9 and HDAC10. The requirement for HDAC9 and HDAC10 in the homologous recombination process was not indirect via blocking the cell cycle progression in an inappropriate point in the cycle. Rather, our results suggest that HDAC9 and HDAC10 are direct participants in the process. Initial attempts to test whether HDAC9 localizes at the site of damage were inconclusive. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that HDAC9 protein is diffusely nuclear, and following ionizing radiation, it remained diffusely nuclear and did not relocalize to foci containing γ-H2AX (supplemental Fig. S2). The HDAC9 was present at the DNA repair foci, but it did not concentrate at the foci after DNA damage. Thus, we cannot rule out that it could be acting indirectly, perhaps via transcriptional regulation. We were unable to carry out localization studies on HDAC10 due to lack of an effective antibody.

HDAC9 has been described as a co-repressor of myocyte enhancer binding factor 2 (MEF2), which represses the expression of myocyte-specific genes (34, 35). HDAC9 also interacts with the NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor 1) corepressor complex (36). HDAC10 has also been found in complex with transcriptional repressors (37, 38).

Because we would expect a transcriptional response required for DNA repair to be stimulatory, as opposed to the transcriptional repressive activity of HDAC9 or HDAC10, it is more likely that HDAC9 or HDAC10 is a direct participant at the site of DNA damage in the homologous recombination process rather than indirect via transcriptional control. Because these histone deacetylases are stimulatory to the homologous recombination process rather than repressive, we feel the most likely scenario is that these histone deacetylases execute an important deacetylation reaction at the site of damage. Current experiments are aimed at finding the critical substrate of this reaction.

A study had shown that treatment with the HDACi PCI-24781 could inhibit homologous recombination via decreased levels of RAD51 protein (39). We tested whether the activities of HDAC9 and HDAC10 affect RAD51 levels. We observed modest increases, not decreases, in levels of RAD51 protein upon HDAC9 or HDAC10 depletion (supplemental Fig. S3). This result is inconsistent with an anticipated indirect effect on homologous recombination of the HDAC9 or HDAC10 proteins via regulation of the expression of other known DNA repair factors.

While we were preparing this manuscript, a recent study was published that found a role for HDAC1 and HDAC2 in nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) via specific deacetylations on H3K56 and H4K16 (40). HDAC1 and HDAC2 depletion increased levels of H3K56Ac at sites of damage and increased DNA damage response signaling. Another study led to the discovery that inhibition of HDAC3 impairs both homologous recombination and NHEJ (41). However, in our study, depletion of HDAC3 did not affect homologous recombination, and this could be attributed to differences in cell lines. Yet another investigation highlighted the importance of SIRT1 (silent information regulator 1), a Class III HDAC, for homologous recombination via Werner syndrome (WRN) helicase (42). We did not pursue this because our HDACi do not affect Class III HDACs (29). In light of all this recent evidence, it is now becoming increasingly apparent that HDACs regulate DNA repair on chromatin. Different HDACs regulate different repair processes: HDAC1 and HDAC2 regulate NHEJ, and HDAC9 and HDAC10 regulate homologous recombination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Burry (Ohio State University Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility) and Dr. Hansjuerg Alder (Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Nucleic Acid Shared Resource) for their technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA141090 from the NCI (to J. D. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S3.

- HAT

- histone acetyl transferase

- HDACi

- histone deacetylase inhibitor(s)

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- HDR

- homology-directed repair

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- VPA

- valproic acid

- NaB

- sodium butyrate

- MMC

- mitomycin C

- BRCA1

- breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein

- NHEJ

- nonhomologous end joining.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ikeda K., Steger D. J., Eberharter A., Workman J. L. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 855–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hebbes T. R., Clayton A. L., Thorne A. W., Crane-Robinson C. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 1823–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kadosh D., Struhl K. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 5121–5127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuo M. H., Zhou J., Jambeck P., Churchill M. E., Allis C. D. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 627–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braunstein M., Sobel R. E., Allis C. D., Turner B. M., Broach J. R. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4349–4356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luo R. X., Postigo A. A., Dean D. C. (1998) Cell 92, 463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glozak M. A., Seto E. (2007) Oncogene 26, 5420–5432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lane A. A., Chabner B. A. (2009) J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 5459–5468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pan L. N., Lu J., Huang B. (2007) Cell Mol. Immunol. 4, 337–343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baylin S. B., Ohm J. E. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6, 107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marks P. A., Xu W. S. (2009) J. Cell. Biochem. 107, 600–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson A. J., Byun D. S., Popova N., Murray L. B., L'Italien K., Sowa Y., Arango D., Velcich A., Augenlicht L. H., Mariadason J. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13548–13558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dokmanovic M., Clarke C., Marks P. A. (2007) Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 981–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bolden J. E., Peart M. J., Johnstone R. W. (2006) Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 5, 769–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ginsburg E., Salomon D., Sreevalsan T., Freese E. (1973) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 70, 2457–2461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boffa L. C., Vidali G., Mann R. S., Allfrey V. G. (1978) J. Biol. Chem. 253, 3364–3366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu P., Martin E., Mengwasser J., Schlag P., Janssen K. P., Göttlicher M. (2004) Cancer Cell 5, 455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Göttlicher M., Minucci S., Zhu P., Krämer O. H., Schimpf A., Giavara S., Sleeman J. P., Lo Coco F., Nervi C., Pelicci P. G., Heinzel T. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6969–6978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kwon S. H., Ahn S. H., Kim Y. K., Bae G. U., Yoon J. W., Hong S., Lee H. Y., Lee Y. W., Lee H. W., Han J. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2073–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han J. W., Ahn S. H., Park S. H., Wang S. Y., Bae G. U., Seo D. W., Kwon H. K., Hong S., Lee H. Y., Lee Y. W., Lee H. W. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 6068–6074 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vigushin D. M., Ali S., Pace P. E., Mirsaidi N., Ito K., Adcock I., Coombes R. C. (2001) Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 971–976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu W. S., Parmigiani R. B., Marks P. A. (2007) Oncogene 26, 5541–5552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garber K. (2007) Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 17–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pierce A. J., Johnson R. D., Thompson L. H., Jasin M. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 2633–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ransburgh D. J., Chiba N., Ishioka C., Toland A. E., Parvin J. D. (2010) Cancer Res. 70, 988–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petrie K., Guidez F., Howell L., Healy L., Waxman S., Greaves M., Zelent A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16059–16072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pujana M. A., Han J. D., Starita L. M., Stevens K. N., Tewari M., Ahn J. S., Rennert G., Moreno V., Kirchhoff T., Gold B., Assmann V., Elshamy W. M., Rual J. F., Levine D., Rozek L. S., Gelman R. S., Gunsalus K. C., Greenberg R. A., Sobhian B., Bertin N., Venkatesan K., Ayivi-Guedehoussou N., Solé X., Hernández P., Lázaro C., Nathanson K. L., Weber B. L., Cusick M. E., Hill D. E., Offit K., Livingston D. M., Gruber S. B., Parvin J. D., Vidal M. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39, 1338–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakanishi K., Yang Y. G., Pierce A. J., Taniguchi T., Digweed M., D'Andrea A. D., Wang Z. Q., Jasin M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1110–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blander G., Guarente L. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 417–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laherty C. D., Yang W. M., Sun J. M., Davie J. R., Seto E., Eisenman R. N. (1997) Cell 89, 349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moynahan M. E., Cui T. Y., Jasin M. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 4842–4850 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Westermark U. K., Reyngold M., Olshen A. B., Baer R., Jasin M., Moynahan M. E. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7926–7936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yuan Z., Seto E. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 2869–2871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou X., Marks P. A., Rifkind R. A., Richon V. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10572–10577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang C. L., McKinsey T. A., Chang S., Antos C. L., Hill J. A., Olson E. N. (2002) Cell 110, 479–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guidez F., Zelent A. (2001) Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 254, 165–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fischer D. D., Cai R., Bhatia U., Asselbergs F. A., Song C., Terry R., Trogani N., Widmer R., Atadja P., Cohen D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6656–6666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lai I. L., Lin T. P., Yao Y. L., Lin C. Y., Hsieh M. J., Yang W. M. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7187–7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Adimoolam S., Sirisawad M., Chen J., Thiemann P., Ford J. M., Buggy J. J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19482–19487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller K. M., Tjeertes J. V., Coates J., Legube G., Polo S. E., Britton S., Jackson S. P. (2010) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1144–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bhaskara S., Knutson S. K., Jiang G., Chandrasekharan M. B., Wilson A. J., Zheng S., Yenamandra A., Locke K., Yuan J. L., Bonine-Summers A. R., Wells C. E., Kaiser J. F., Washington M. K., Zhao Z., Wagner F. F., Sun Z. W., Xia F., Holson E. B., Khabele D., Hiebert S. W. (2010) Cancer Cell 18, 436–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uhl M., Csernok A., Aydin S., Kreienberg R., Wiesmüller L., Gatz S. A. (2010) DNA Repair 9, 383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.