Abstract

PKR is a potent antiviral molecule that can terminate infection by inhibiting protein synthesis and stimulating NF-κB activation and apoptosis. Originally, it was thought that only intermediate and late gene transcription produced double-stranded (ds) RNA to activate PKR during vaccinia virus (VACV) infection. The VACV E3 or K3 proteins squelch this effect by binding to either dsRNA or PKR. However, in the absence of the K1 protein, VACV infection activates PKR at very early times post-infection and despite the presence of E3 and K3. These data suggest that VACV infection induces PKR activation by a currently unknown mechanism. To determine this mechanism, cells were infected with K1L-containing or -deficient VACVs. By using conditions that limited the progression of the poxvirus replication cycle, we observed that early gene transcripts activated PKR in RK13 cells, identifying a new PKR-activating mechanism of poxvirus infection. Using a similar approach for HeLa cells, intermediate gene transcription was sufficient to activate PKR. RNA isolated from infected RK13 or HeLa cells maintained PKR-activating properties only when dsRNA was present. Moreover, viral dsRNA was directly detected in infected cells either by RT-PCR or immunofluorescent microscopy. Interestingly, dsRNA levels were higher in infected cells in which the K1 protein was nonfunctional. Only K1 proteins with PKR inhibitory function prevented downstream NF-κB activation. These results reveal a new PKR activation pathway during VACV infection, in which the K1 protein reduces dsRNA levels early in VACV infection to directly inhibit PKR and several of its downstream antiviral effects, thereby enhancing virus survival.

Keywords: NF-kappa B, Protein Kinase RNA (PKR), Pox Viruses, Viral Transcription, Virus

Introduction

Protein kinase RNA-activated (PKR) is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates several cellular events (1). During a viral infection, PKR binds to viral dsRNA3 of >30 bp in length, resulting in PKR dimerization, phosphorylation, and activation. The activated PKR stimulates several antiviral effects; PKR phosphorylates eIF2α, an event that halts viral protein synthesis to abort an infection. Additionally, PKR activates NF-κB in virus-infected cells to induce a pro-inflammatory immune response. PKR also stimulates apoptosis, lysing virus-infected cells (2).

Vaccinia virus (VACV) is a well studied poxvirus. It has a dsDNA genome that is expressed and replicated in the cytoplasm of host cells (3). Its early, intermediate, and late classes of genes are expressed in a temporal cascade (3). VACV infection produces dsRNA at later times in replication, during the transcription of viral intermediate or late genes (4). Poxvirus intermediate and late gene transcripts are heterogeneous at their 3′ ends (3). Thus, transcripts from one DNA strand can often read through into regions of the genome that are transcribed from the opposite strand, resulting in the synthesis of significant quantities of complementary RNAs that form dsRNAs (3). VACV expresses the E3 and K3 proteins to prevent dsRNA-PKR interactions at this later time post-infection (5, 6).

It is thought that VACV early RNAs do not activate PKR; early gene transcripts are uniform in size due to the presence of cis-acting elements that are expected to ensure their precise termination (4). However, in our previous studies, we observed PKR activation at early times post-infection (7). Briefly, VACVs lacking a wild-type K1L gene (ΔK1L) activate PKR soon after infection, whereas wild-type VACVs do not (7). Moreover, PKR activation occurs despite the lack of intermediate and/or late gene transcription (8), and PKR is activated despite the simultaneous expression of the VACV E3 and K3 proteins (7, 9). These data suggest that a heretofore unappreciated early event in the virus replication cycle activates PKR.

To identify the early event(s) that trigger PKR activation, cells were infected with VACV variants in which the K1 protein either inhibited or allowed virus-induced PKR activation. The PKR activation state was evaluated under conditions that blocked different stages of the poxvirus replication cycle. The ability of RNAs purified from virus-infected cells to stimulate PKR activation independent of infection also was determined. Additionally, reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) and confocal microscopy were used to detect and compare dsRNA levels in infected cells at early and intermediate times post-infection. Because one downstream effect of PKR is NF-κB activation (9–11), we also evaluated whether VACV-induced PKR activation was responsible for NF-κB activation.

Results from these studies showed that PKR-activating viral dsRNAs were generated by early gene transcripts in RK13-infected cells, identifying a new PKR-activating mechanism possessed by VACV. The absence of K1L during VACV infection of HeLa cells possessed a different phenotype; PKR-activating viral dsRNAs were generated by intermediate gene transcripts. Importantly, for both cell lines, in the absence of K1L, virus-induced PKR activation resulted in NF-κB activation. By identifying how VACV stimulates PKR early in infection, a more refined understanding of PKR regulation and function during infection will evolve.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Viruses, and Plasmids

Human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) or rabbit kidney epithelial (RK13) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. HeLa cells in which >95% of PKR is stably knocked down (PKRkd) were obtained from Dr. Charles Samuel (Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara) (12).

The wild-type Western Reserve (WR) and the attenuated modified Ankara (MVA) strains of VACV were used in these studies. Virus ΔK1L is a mutant WR variant in which the K1L gene is deleted, whereas virus MVA/K1L is a recombinant MVA in which the K1L gene from vaccinia virus strain WR was stably inserted into the MVA genome (13). Five previously described recombinant viruses containing wild-type or mutated K1L genes were used as follows: vC7L− K1L+, S2N, S2C, S2C#2, and S2C#3 (14). All viruses lack the C7L gene. vC7L− K1L+ was created by stably re-inserting a V5 epitope-tagged K1L gene and its natural promoter into virus vC7L− K1L− (14). Virus S2N was similarly created by the insertion of a K1L gene whose product was mutated at residues 63, 67, and 70–75 (in the N-terminal portion of the 2nd ankyrin repeat; ANK2) into vC7L−K1L− (14). Virus S2C encodes a mutated K1 product, in which ANK2 C-terminal residues 78, 79, 82, 83, 85, and 87–90 are mutated (14). Viruses S2C#2 and S2C#3 express mutant K1L products in which the ANK2 C-terminal residues 81, 82, and 84 or 86–88 are mutated, respectively (14).

Plasmid pK1L was created by PCR amplification of the K1L gene in which a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag sequence was engineered onto the N terminus of the gene. The amplicon was cloned into plasmid pCI such that the expression of the recombinant K1L gene was under the control of the CMV promoter.

Conditions for Virus Infections

Confluent cellular monolayers were either mock-infected or infected with the indicated virus at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 10 plaque-forming units/cell as described (7). In some experiments, monolayers were incubated with cordycepin (COR; 40 μg/ml; Sigma), canavanine (1 mm; Sigma), or cytosine arabinoside (Ara C; 40 μg/ml; Sigma) for 30 min prior to viral inoculation as well as during the adsorption stage of infection and for the duration of the infection. In another experiment, cells were incubated with extract from the Sarracenia purpurea plant (SPE; a gift from Dr. Jeffrey Langland).4 The crude plant extract was supplied in 45% ethanol (EtOH), from which an aliquot of extract was filtered using a 0.2-μm syringe filter followed by partial EtOH evaporation in a speed vacuum for 30 min. After an adsorption incubation time of 10 min, virus was removed, and the cell monolayers were washed with complete medium twice, after which complete medium either lacking or containing SPE was added for the duration of the infection.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cytoplasmic proteins were extracted from virus-infected cells using a modified protocol described previously (13). The protein concentration of each sample was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce), and 25 μg of protein from each sample was analyzed by immunoblotting. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-eIF2α S51 (1:1,000; Epitomics); mouse monoclonal anti-eIF2α (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-phospho-PKR Thr-446 (1:1,000; Epitomics); mouse monoclonal anti-PKR N terminus (1:1,000; Epitomics); mouse monoclonal anti-E3L antibody (1:1,000; a gift from Dr. Stuart Isaacs, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania) (16); or mouse monoclonal anti-HA antiserum (1:1,000; Sigma). Either horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:10,000; Calbiochem) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000; Fisher) was used for secondary antibodies. Immunoblots were developed using SuperSignal West chemiluminescence reagents per the manufacturer's directions (Pierce) followed by detection by the application of x-ray film (Eastman Kodak Co.).

Gel Electromobility Shift Assays of Nucleus-extracted Proteins

The method for isolating nuclear proteins from virus-infected cells and assaying proteins for the presence of NF-κB was described previously (17). Briefly, 5 (RK13) or 2 μg (HeLa) of each extract was incubated with 0.35 pmol of a 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probe in gel shift assay system binding buffer (Promega) as per the manufacturer's directions. Oligonucleotides containing the rabbit MMP-9 promoter (5′-CCCCGGTGGAATTCCCCAAATCCT-3′) and (5′-AGGATTTGGGGAATTCCACCG-GGG-3′) were annealed, and the resultant double-stranded oligonucleotide was used as a probe for nuclear extracts from RK13-infected cells in our laboratory (18). Similarly, oligonucleotides containing the human TLR2 promoter NF-κB-binding site (5′-AGTAGATCTCGGACATACGGACATCTGTGCAGAG-3′) and (5′-AGCTAAGCTTTGGGAGAACTCCGAGCAGTCAC-3′) were annealed and used as a double-stranded oligonucleotide probe for nuclear extracts from HeLa cells (19). Some reactions also included 1 μl of monoclonal anti-p65 antiserum. Reactions were electrophoretically separated in a 6% acrylamide gel (Invitrogen) under nondenaturing conditions. Images of dried gels were detected and analyzed by using the ImageGauge and ImageReader programs (Fuji).

Reverse Transcriptase-PCR

RK13 cellular monolayers were either mock-infected or infected with WR in the absence or presence of SPE (see above). Total RNA was harvested from infected cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit per manufacturer's instructions. A portion of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into single-stranded cDNA with ImProm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega) and oligo(dT) primers. Amplifications of E3L and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA were performed in parallel by using PCR and primers specific for the VACV E3L gene and rabbit (RK13) GAPDH gene. Primers for VACV E3L were 5′-GCAGAGATTGTGTGTGCGGCTATT-3′ and 5′-GGTGACAGGGTTAGCATCTTTCCA-3′, yielding a 326-bp amplicon. PCR conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 30 s for 25 cycles. Primers for rabbit GAPDH were 5′-CAAGCCTCTAGCCCACGTA-3′ and 5′-GGCAATGATCCCAAAGTAG-3′, yielding a 438-bp product (13). PCR conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, 62 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 30 s for 25 cycles. An aliquot of each PCR was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and amplicons were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Transfection of RNA Isolated from Virus-infected Cells

RK13 and HeLa cellular monolayers were mock-infected or infected as described above. For some experiments, cellular monolayers were treated with Ara C as described above. At the times indicated post-infection (pi), cells were lysed, and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. Next, DNA was digested from each sample using the Turbo DNA-free system (Applied Biosystems). Total RNA was quantified, and HeLa cells were transfected with either 3 (HeLa) or 5 μg (RK13) of RNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 6 h post-transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in CE buffer, and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting as described above. In some reactions, RNA was incubated with RNases prior to transfections. Here, 3 (HeLa) or 5 μg (RK13) RNA were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in either buffer containing the following: (i) 0.6 unit of RNase V1 (Ambion) or (ii) 6 ng of RNase A (Ambion) and 6 units of T1 (Ambion) or (iii) reaction buffer alone. The treated RNAs were then transfected into subconfluent HeLa cell monolayers, and cells were incubated for 6 h after which total cellular RNA was harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting (described above).

Ectopic Expression of K1

Subconfluent HeLa cell monolayers were transfected with either 2 μg of pCI or pK1L using Lipofectamine 2000. At 18 h post-transfection, cells were either mock-transfected or transfected with poly(I-C) (Sigma) or 3 μg of total RNA isolated from S2C#2- or S2C#3-infected cells. At 6 h post-transfection, cytoplasmic proteins were harvested and evaluated by immunoblotting (as described above) for PKR activation.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

HeLa cells grown on glass coverslips (Fisher) were mock-infected or infected with either vC7L−K1L+ or S2C#2 (m.o.i. = 10). At 3 h pi, cell monolayers were fixed in a 3% paraformaldehyde solution (Fisher) and then permeabilized with a 0.1% saponin solution (Sigma). The treated monolayers were incubated in blocking buffer (3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS) for 1 h and then incubated in blocking buffer alone or blocking buffer containing mouse monoclonal anti-dsRNA (J2) antibody (1:1,000; English and Scientific Consulting). After 1 h, monolayers were washed with blocking buffer and subsequently incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer containing biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch). After washing as above, the monolayers were incubated in blocking buffer containing streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 fluorochrome (1:200; Molecular Probes). After 20 min, the monolayers were washed and incubated in a solution containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:1,1000; Molecular Probes) for 10 min. Finally, monolayers were washed with PBS and mounted on microscope slides using hydromount (National Diagnostics). All incubations proceeded at room temperature. Images were acquired by using the Olympus BX51 immunofluorescence microscope, using the ×40 objective. Intracellular fluorescent particles were detected and counted using ImageJ software. Using slides prepared in triplicate, 50 cells per slide were analyzed for the number of cells that possessed one or more fluorescent particles. The number of fluorescing cells per slide was tallied, and the average for the three replicates was determined. Results were recorded in graph form.

Detection of Viral dsRNA Using RT-PCR

Confluent RK13 cellular monolayers were either mock-infected or infected with either WR or ΔK1L in the presence of Ara C (described above). Total RNA was isolated from infected cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit, and contaminating DNA was digested using the Turbo DNA-free DNase kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two μg of RNA from each sample were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in buffer containing the following: (i) 2 μl of RNase A/T1 mixture (Ambion) or (ii) 2 μl of RNase A/T1 mixture and 0.6 unit of RNase V1 (Ambion) or (iii) buffer alone for a total volume of 20 μl. Following digestion, RNA was purified using a Zymo Research Clean and Concentrator column according to manufacturer's directions. Prior to reverse transcription, RNA samples were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min to denature dsRNA to ssRNA. One μl of RNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture was reverse-transcribed (RT) into single-stranded cDNA with ImProm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega), using a primer specific for the RNA predicted to be present in the overlapping complementary RNA region. The specific reverse transcription primer for the amplification of the A4L-A5R RNA region was 5′-CGTCTAGTATAGCGTCG-3′, and the reverse transcription primer specific for amplification of the A46R-A47L RNA region was 5′-CATTGTGTTACAGAATC-3′. Next, PCR amplifications of the cDNA from the A4L-A5R and A46R-A47L regions were performed by using primers that were specific for these two regions of interest. Primers for VACV A4L-A5R region were 5′-ATGGCAGACACAGACG-3′ and 5′-AGCGTCGTTTAAGAGCAG-3′, yielding a 217-bp product. PCR conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, 51 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 30 s for 30 cycles. Primers for VACV A46R-A47RL region were 5′-CAGGGAAACGGATGTATA-3′ and 5′-TGTGTTACAGAATCATATAAGG-3′, yielding a 104-bp product. PCR conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, 47 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 30 s for 35 cycles. A portion of each PCR was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and amplicons were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. For some reactions, the RT step was eliminated, and viral RNAs were incubated with nested primers to ensure than no contaminating DNA was present in RNA extracts. For other reactions, a portion of the RT reaction was added to PCRs lacking nested primers and then analyzed by gel electrophoresis to ensure that the RT step did not result in the amplification of a nonspecific cDNA product.

RESULTS

PKR Is Activated by Early Gene Transcription in RK13 Cells

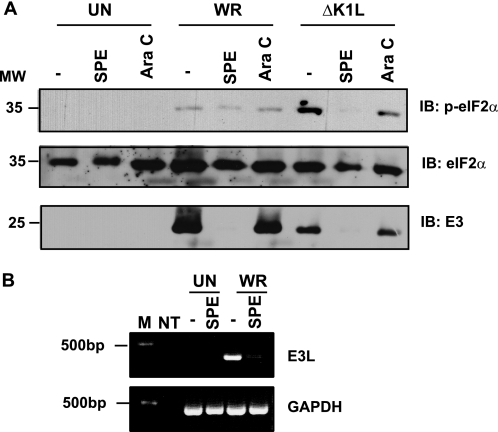

We previously published that a mutant VACV lacking a wild-type K1L gene (ΔK1L) activates PKR (by virtue of its ability to stimulate eIF2α phosphorylation) in the rabbit RK13 cell line (7). PKR activation occurs early after infection and despite the simultaneous expression of the VACV E3 protein (7). We hypothesized that dsRNA generated from early viral gene transcription stimulated PKR and that the VACV K1 protein would inhibit this trigger of PKR activation. In support of this hypothesis, ΔK1L infection of RK13 cells is abortive, with only early gene transcription occurring (8). Similar to our previous publication (7), ΔK1L infection activated PKR to a greater extent than WR, as was evidenced by the increased intensity of the phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) band (Fig. 1A). To ensure that transcription of only early viral genes occurred, infections proceeded in the presence of cytosine Ara C, a drug that prevents viral intermediate and late gene expression indirectly through inhibiting viral genome replication. As expected, the phosphorylated form of eIF2α remained present when ΔK1L infection proceeded in the presence of Ara C. In contrast, p-eIF2α levels remained low in WR-infected cells regardless of Ara C treatment, presumably because of the presence of the VACV early K1L gene product.

FIGURE 1.

Virus-induced PKR activation requires early gene transcription. RK13 cellular monolayers were mock-infected (UN) or incubated with either WR or ΔKIL (m.o.i. = 10) in medium lacking or containing SPE or Ara C. At 3 h pi, cells were harvested and lysed. A, 25 μg of cytoplasmic proteins from each sample were analyzed by immunoblotting. Immunoblots (IB) were incubated with antibodies to detect phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) or unmodified eIF2α. The same immunoblots were incubated with antiserum specific for the vaccinia virus E3 protein (E3). Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated. A representative immunoblot is shown here. B, total RNA was isolated from each lysate and was subjected to reverse transcription PCR for E3L and GAPDH mRNA. The resultant amplicons were separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide. As a negative control, no template (NT) was used for PCRs with E3L and GAPDH primers. M, molecular weight marker.

Recently, extracts from SPE were identified to allow VACV attachment and entry into the host cell but inhibit early gene transcription, preventing the accumulation of viral RNA within infected cells.4 SPE treatment of cells prevents the expression of the early E3L gene, as detected by quantitative real time PCR, as well as other early genes, as detected by [35S]methionine labeling of virus-infected cells.4 We found similar trends using semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR to demonstrate that SPE inhibited the transcription of a representative early gene (E3L) (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 1B, there was a dramatic decrease in the VACV E3L amplicon intensity when WR infections occurred in the presence versus the absence of SPE. This inhibition was specific as the treatment did not alter levels of cellular GAPDH transcripts. Accordingly, the E3 protein, as measured by immunoblotting, was absent when infections occurred in the presence of SPE (Fig. 1A).

When SPE was present during infection, eIF2α phosphorylation in ΔK1L-infected cells was no longer detected (Fig. 1A), implying that early gene transcription was responsible for stimulating PKR activation. As would be expected, the presence of SPE did not induce eIF2α phosphorylation in cells that were either mock-infected or infected with WR. Unmodified eIF2α proteins were present in similar amounts in each sample, ruling out the possibility that differences in the p-eIF2α levels were due to uneven protein loading. Cordycepin has been reported to inhibit early gene transcription (20). Unfortunately, cordycepin treatment was ineffective in RK13 cells, as indicated by the abundant presence of the early E3 proteins when infections occurred in the presence of this drug (data not shown).

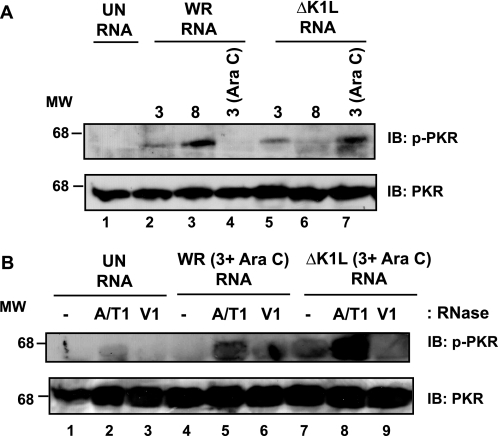

dsRNA Isolated from Infected RK13 Cells Possesses PKR Activating Properties

The above studies established that an event associated with viral early gene transcription activated PKR in RK13 cells. We hypothesized that viral early gene transcription produced dsRNA capable of activating PKR. To test this, RNA was isolated from virus-infected RK13 cells and subsequently transfected into HeLa cells. Transfected HeLa cells were evaluated for PKR activation (p-PKR) by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2A, PKR remained inactive when cells were transfected with RNA from uninfected cells. In contrast, RNA harvested from WR-infected RK13 cells activated PKR. This result was expected because intermediate and late gene transcription occurs during this time (3). PKR activation increased as infection times increased (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3), reflective of the fact that intermediate and late gene transcription increased as infections proceeded. Furthermore, the PKR activating dsRNA from WR-infected cells harvested at 3 h post-infection (Fig. 2A, lane 2) was due to intermediate gene transcripts because PKR was no longer activated when using RNA isolated from cells infected with WR in the presence of Ara C (Fig. 2A, lane 4). RNA from ΔK1L-infected cells retained their PKR-activating properties when infections occurred in the absence or presence of Ara C (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 7), implying that early gene transcripts formed dsRNA molecules. However, RNA harvested at 8 h post-infection possessed lower PKR-activating capacity than RNA harvested at 3 h post-infection. We note that in a previous publication (7), PKR activation in virus-infected cells was seen to a similar degree, indicating that the differences observed in phospho-PKR levels in transfected cells is relevant to what we observed during infection.

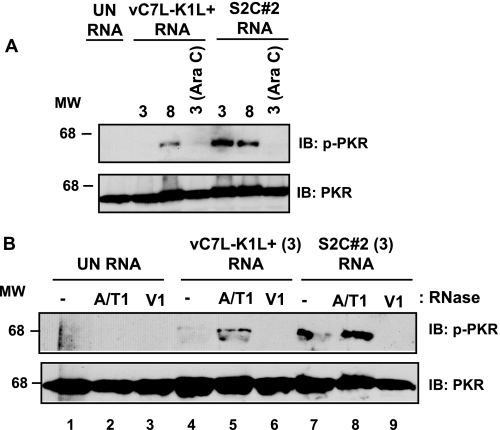

FIGURE 2.

dsRNA from virus-infected cells activates PKR. RK13 cellular monolayers were incubated in medium lacking (−) or containing Ara C (40 μg/ml) and were either mock-infected (UN) or infected with either WR or ΔK1L (m.o.i. = 10). At the indicated times post-infection, cells were harvested and lysed. Total RNA was extracted and incubated with DNase. Five μg RNA was either incubated in buffer alone (A and B) or in buffer containing either RNase A and RNase T1 (A/T1) or RNase V1 (V1) (B). HeLa cells were transfected with RNA reactions using Lipofectamine 2000. At 6 h post-transfection, cells were harvested and lysed, and 25 μg of cytoplasmic protein was analyzed by using immunoblotting. Immunoblots (IB) were incubated with antibodies against phosphorylated PKR (p-PKR) or unmodified PKR. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated.

One concern was that PKR activation was due to nascent proteins synthesized from transfected viral RNA. To address this possibility, the same immunoblots from Fig. 2A were evaluated for the presence of the VACV early E3L product. The E3 protein was not detected, indicating viral proteins were likely not synthesized from transfected RNA (data not shown).

To identify whether viral dsRNA induced PKR activation, we repeated the above transfection assays using RNA that was incubated with RNases to degrade either single-stranded RNA (ssRNA; RNase A/T1) or dsRNA (RNase V1) prior to transfection. The same RNA samples used in Fig. 2A were used for experiments in Fig. 2B to allow for direct comparison of PKR activating activity of RNAs. Similar to Fig. 2A, a low level of PKR was activated when HeLa cells were transfected with RNA isolated from Ara C-treated, ΔK1L-infected cells (Fig. 2B, lane 7). The PKR-activating property was due to dsRNA because phospho-PKR was not detected when RNA from ΔK1L-infected cells had been incubated with RNase V1 (Fig. 2B, lane 9). RNA that was digested with a combination of RNases A and T1, thereby digesting ssRNA, activated PKR when transfected into HeLa cells (Fig. 2B, lane 8). Interestingly, this later p-PKR band was more intense as compared with its untreated RNA. When assaying RNA from WR-infected cells, very little phospho-PKR was detected (Fig. 2B, lane 4), consistent with results described in Fig. 2A. Incubation with RNase A/T1 elicited PKR activation (Fig. 2B, lane 5), albeit at reduced levels when considered to comparably treated RNA from ΔK1L-infected cells (lane 8). RNA from WR-infected cells treated with RNase V1 did not activate PKR upon transfection into HeLa cells, again indicating the specific role of dsRNA in this pathway. (It should be noted that a nonspecific oval-shaped spot is present in Fig. 2B, lane 6.) As expected, RNAs from mock-infected cells that were incubated with either RNase treatments failed to activate PKR. We conclude from these studies that viral dsRNA generated from early gene transcription is present, as measured by its ability to activate PKR. Furthermore, the lack of the K1 protein during virus infection results in increased phospho-PKR levels, implying that the K1 protein was responsible for decreasing dsRNA levels.

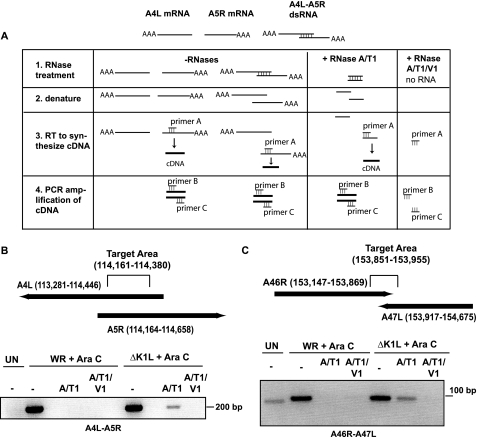

Virus-derived dsRNA Is Present after Early Gene Transcription

The next goal was to demonstrate that viral dsRNA was indeed formed in infected cells by the hybridization of early gene transcripts. The recent sequencing of the vaccinia virus genome showed that there were some early gene transcripts that overlapped and had the potential of forming dsRNA of sufficient length to activate PKR (2, 21).5 One such region includes mRNA from the A4L and A5R early genes (Fig. 3B). These mRNAs are partially complementary because the transcription start site for the leftward-transcribed A4L gene occurs 282 bases downstream of the transcription start site of the rightward-transcribed A5R gene (Fig. 3B) (21). Thus, the overlapping RNA is though to occur at nts 114,161–114,380. A second region occurs between the A46R and A47L genes. For the A46R and A47L RNAs, the overlap was predicted to be from nts 153,147 to 153,869 (Fig. 3C). Our goal was to assess if these complementary RNAs indeed formed dsRNA during infection. A diagram of our approach is shown in Fig. 3A. To evaluate if dsRNA from these regions existed in infected cells, RNA was collected from virus-infected RK13 cells, in which intermediate or late viral transcription was blocked. We collected total RNA from infected cells and then performed a reverse transcriptase step, using unique primers that would only bind to the specific overlapping dsRNA region we were targeting (Fig. 3A). For example, for the A4L-A5R dsRNA, we used a primer that specifically bound to the A5R RNA within nt 114,161–114,380 (Fig. 3A). Then we PCR-amplified the resultant cDNA using a set of primers nested within the cDNA that was predicted to include the dsRNA region. All oligonucleotide primers used for these studies were compared with the vaccinia virus and rabbit genomes to confirm that primers would not bind to any other RNA or DNA regions. Indeed, no such amplicon was PCR-amplified when using RNA from mock-infected cells (Fig. 3, B and C). In addition, we performed experiments in parallel in which either the RT step was removed or in which the nested primers were absent. In both cases, no PCR amplicon was observed, indicating the specificity of the reaction (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Detection of early viral dsRNA in RK13 cells using RT-PCR. A, illustration of the approach used to detect and amplify dsRNA from virus-infected cells. Total RNA isolated from mock- or virus-infected cells was incubated in the absence or presence of the indicated RNases. Next, RNA was heated to denature dsRNA complexes into ssRNA. A primer specific for one of the strands of RNA (primer A; in this example, a primer specific for A5R RNA) was incubated with RNA for one round of reverse transcription (RT). Resultant cDNA was then incubated with primers nested within the predicted dsRNA region (primers B and C; in this case primers B and C were within the predicted area of dsRNA, which is predicted to be within the target area of nt 114,161–114,380). cDNA, if present, was PCR-amplified. Using this approach, it was expected that ssRNA or dsRNA would be detected when RNA was not treated with RNases. However, when RNA was treated with RNase A/T1, only dsRNA would be present. The addition of RNase A/T1 and V1 was expected to degrade all RNA, yielding no RT product. B and C, RK13 cellular monolayers were mock-infected (UN) or infected with either WR or ΔK1L (m.o.i. = 10) in the presence of Ara C (40 μg/ml). At 2 h pi, cells were harvested and lysed. Total RNA was isolated from each lysate, and contaminating DNA was removed. Two μg of RNA from each sample were incubated either in buffer alone (−) or buffer containing RNase A/T1 or RNase A/T1/V1 for 1 h. RNA was boiled for 5 min. RNA was reverse-transcribed using a primer that specifically annealed to RNA present in the predicted overlapping regions for either A4L and A5R (B) or A46R and A47L (C). Resultant cDNA was PCR-amplified using nested primers that would recognize the proposed overlapping regions (target area is nts 114,161–114,380 for A4L-A5 overlapping regions and nts 153,851–153,869 for A46R-A47L overlapping regions). A portion of each reaction separated by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide staining.

Regardless of the infecting virus, only one amplicon of the predicted size was produced from undigested RNA samples from virus-infected cells, indicating that the target RNA was present (Fig. 3B) and that the primers were specific for amplifying only the region of interest. Digestion of RNA from WR-infected cells with RNases (A/T1 or including V1) ablated the amplification of cDNA, implying that the wild-type viral A4L and A5R mRNAs did not form dsRNA duplexes in the presence of K1L. In contrast, some of the ΔK1L A4L-A5L RNA existed as dsRNA because an amplicon was still detected if RNA was digested with RNase A/T1 before RT-PCR (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the addition of RNase V1 to the ΔK1L RNA samples eliminated the presence of an amplicon, which indicated that dsRNA was responsible for the amplification of the A4L-A5R region.

A second event that produces mRNA with complementary sequences is the rightward transcription of the A46R and leftward transcription of the A47L early genes. In this case, the 3′ ends of each transcript overlap with each other about 100 nts (21) and could hybridize to form dsRNA. Similar to the above findings, RNA from WR or ΔK1L-infected cells yielded PCR products of the appropriate size (∼100 bp; Fig. 3C), indicating that the target RNA was indeed present in RNA extracted from virus-infected cells. Digestion of WR RNA with RNases (A/T1 or including V1) ablated the amplification of cDNA, implying that the A46R and A47L mRNAs remained single-stranded in a wild-type infection. In contrast, an amplicon was detected when using RNA from ΔK1L-infected cells digested with RNases A/T1, implying that dsRNA was present in RNA extracts. The addition of RNase V1 to RNA samples eliminated the presence of an amplicon, which indicated that the amplification of the A46R-A47L region was indeed due to dsRNA and not to incomplete digestion of RNA.

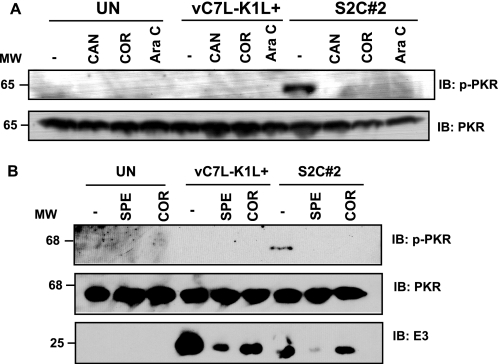

PKR Is Activated by Intermediate Gene Transcription in HeLa Cells

We tested the viral source for PKR activation in the human HeLa cell line to assess whether the ability of early gene transcripts to activate PKR was not simply a cell line phenomenon. When studying VACV-induced PKR activation in HeLa cells, both the K1L and C7L genes of WR must be absent or mutated for virus-induced PKR activation of HeLa cells (7, 22). Thus, all viruses used for studies with HeLa cells were in a vC7L−K1L− background (7, 14). Interestingly, the mutant viruses that activate PKR in HeLa also cannot progress past intermediate mRNA translation (23), giving us the added benefit of studying PKR activation independent of late gene transcription.

To identify whether early or intermediate gene transcripts activated PKR, HeLa cells were infected with viruses containing a wild-type K1L gene (vC7L−K1L+) that inhibits PKR activation or a mutant K1L gene (S2C#2) that allows PKR activation (7), under conditions in which either early or intermediate gene transcription was inhibited. Virus S2C#2 was used instead of virus vC7L−K1L− because both viruses have the same PKR activation phenotype and S2C#2 routinely grows to higher titers (data not shown).6 Results are shown in Fig. 4. In this cell line, Ara C treatment of S2C#2-infected cells prevented PKR activation, indicating that intermediate gene transcripts activated PKR. As would be expected, the decrease of early gene transcription by SPE4 or COR (24, 25) (as indicated by diminished E3 proteins, Fig. 4B) or early protein translation by canavanine (25) prevented PKR activation because the virus replication cycle was inhibited at an event that preceded intermediate gene transcription.

FIGURE 4.

Intermediate gene transcription stimulates virus-induced PKR activation in HeLa cells. HeLa cellular monolayers were incubated in medium lacking (−) or containing canavanine (CAN; 100 mm), COR (40 μg/ml), or Ara C (40 μg/ml) (A) or SPE or COR (B). Cells were mock-infected (UN) or infected with either vC7L−K1L+ or S2C#2 (m.o.i. = 10). At 4 h pi, cells were lysed, and 25 μg of protein from each sample was analyzed by immunoblotting. Immunoblots (IB) were probed with antibodies recognizing the phosphorylated form of PKR (p-PKR) and then re-probed with antibodies recognizing the unmodified form of PKR (PKR). The same immunoblot was incubated with antibodies recognizing the VACV E3 protein. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated.

dsRNA Generated by Intermediate Gene Transcription Stimulates PKR Activation in HeLa Cells

We next evaluated the PKR-activating ability of transfected RNA isolated from virus-infected HeLa cells (Fig. 5). As would be anticipated, RNA isolated from uninfected cells did not elicit PKR activation when transfected into HeLa cells (Fig. 5A). When using RNA extracted from vC7L−K1L+-infected cells, active PKR was detected only when using RNA extracted from cells 8 h post-infection, a time in which intermediate and late gene transcription has occurred. Because PKR remained inactive when infections proceeded in the presence of Ara C, intermediate or late gene transcripts must possess PKR-activating function. When studying RNA isolated from S2C#2-infected cells, RNA activated PKR to a greater extent than RNA from vC7L−K1L+-infected cells, implying that the wild-type K1 protein decreased the quantity of dsRNA in infected cells. Because S2C#2 infection of HeLa cells does not proceed past intermediate gene transcription (23), the PKR-activating effects must be due to intermediate gene transcripts. In support of this, Ara C treatment of virus-infected cells inhibited PKR activation, indicating that early gene transcripts were insufficient to stimulate PKR. We observed identical results when these same RNA samples were transfected into the human 293T cell line (data not shown). The same immunoblots from Fig. 5A were evaluated for the presence of the VACV E3 proteins. No E3 proteins were detected, ruling out that viral proteins synthesized from transfected RNA were PKR-activating (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

dsRNA isolated from virus-infected HeLa cells activates PKR. HeLa cellular monolayers were incubated in medium lacking (−) or containing Ara C (40 μg/ml), and cells were mock-infected (UN) or infected with either vC7L−K1L+ or S2C#2 (m.o.i. = 10). At either 3 or 8 h pi, cells were harvested and lysed using TRIzol. Total RNA from each sample was isolated and treated with DNase. Three μg of RNA was transfected into HeLa monolayers (A) or incubated in buffer alone (−) or in buffer containing either RNase A/T1 or RNase V1 for 1 h (B). Next, RNA was transfected into HeLa cells. At 6 h post-transfection, cells were harvested and lysed, and 25 μg of cytoplasmic protein from each sample was analyzed by immunoblotting. Immunoblots (IB) were incubated with antibodies against either the phosphorylated (p-PKR) or unmodified (PKR) form of PKR. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated.

We evaluated the effect of RNase digestion on PKR-activating function of RNAs collected from cells 3 h post-infection (Fig. 5B). As in Fig. 5A, phospho-PKR was detected when cells were transfected with RNA isolated from S2C#2-infected cells (Fig. 5B, lane 7) but not from RNA isolated from vC7L−K1L+-infected cells (Fig. 5B, lane 4). RNA samples retained their PKR-activating property when digested with the ssRNA-specific RNases A and T1 (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 8). However, RNase V1 digestion eliminated the PKR-activating function (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 and 9), indicating that dsRNAs were responsible for activating PKR. No PKR activation was observed when RNA from mock-infected cells was used for transfection regardless of RNase treatment prior to transfection (Fig. 5B, lanes 1–3).

dsRNA Is Detected in Infected Cells in Situ

The above assays demonstrated that RNA generated by intermediate gene transcription possessed PKR-activating properties in HeLa cells. We sought to identify dsRNA in virus-infected HeLa cells in situ as direct evidence that dsRNA was indeed present when intermediate gene transcription occurred. To this end, infected cells were fixed and incubated with an anti-dsRNA antibody previously shown to detect dsRNA in virus-infected cells when using immunofluorescence microscopy (26). Infected cells were fixed at 3 h post-infection, a time at which dsRNA from intermediate but not late gene transcription has occurred (Fig. 5A). Although this antibody detected dsRNA from virus-infected HeLa cells (Fig. 6A), it did not identify dsRNA in RK13 cells infected with VACVs (data not shown), preventing us from performing similar assays with infected RK13 cells. Infected HeLa cells were fixed at 3 h post-infection, a time at which dsRNA from intermediate, but not late, gene transcription has occurred (Fig. 5).

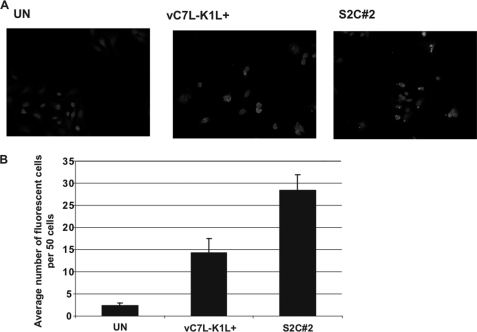

FIGURE 6.

dsRNA is present in virus-infected cells in situ. HeLa cell monolayers were either mock-infected (UN) or infected with either vC7L−K1L+ or S2C#2 (m.o.i. = 10). At 3 h pi, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with anti-dsRNA antibody, followed by incubation with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody. Next, samples were incubated with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 594, followed by incubation in a DAPI-containing solution. Cells were examined using immunofluorescence microscopy (×40 objective). A, representative fields are shown. B, using images from slides prepared in triplicate, 50 cells per slide were analyzed for the number of cells that possessed at least one fluorescent particle (positive staining). The number of positive cells per 50 cells counted was tallied and averaged.

Representative images of mock- or virus-infected HeLa cells are shown in Fig. 6A. A relatively low level of background fluorescence was observed in uninfected cells. In contrast, increased intracellular fluorescence in a pattern that surrounded the nuclei was observed in cells infected with vC7L−K1L+. dsRNA also was present in S2C#2-infected HeLa cells, as was evidenced by the presence of fluorescence that consisted of a punctate pattern as observed, similar to those observed previously in VACV-infected cells at 24 h post-infection or in cells transfected with poly(I-C) (26, 27). For all virus-infected cells, the observed fluorescence was intracellular and not due to extracellular debris as nonpermeabilized cell controls lacked this pattern of fluorescence (data not shown). Using slides prepared in triplicate, 50 cells per slide were analyzed for the number of cells that possessed one or more fluorescent particles. The number of fluorescing cells per slide was tallied, and the average was determined (Fig. 6B). A 2-fold increase in the number of fluorescent cells was observed when comparing S2C#2-infected cells to cells infected with vC7L−K1L+, suggesting that the K1 protein diminishes the amount of viral dsRNA during infection. Interestingly, there were greater numbers of S2C#2-infected cells with multiple fluorescent particles per cell than vC7L−K1L+-infected cells (data not shown).

Ectopically Expressed VACV K1 Protein Inhibits PKR Activation Induced by Synthetic or Cell-associated dsRNA

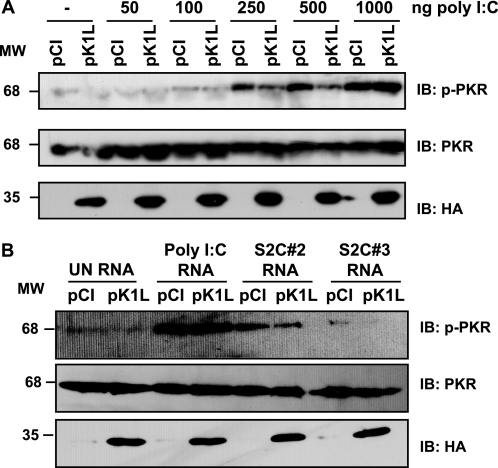

The above experiments used a virus infection model to study PKR activation. To ascertain whether the K1 protein possessed PKR inhibitory function independent of infection, cells were transfected with a K1L-containing plasmid (pK1L), and the ability of K1 to inhibit poly(I-C)-induced PKR activation was evaluated. Levels of phosphorylated or native PKR were determined by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 7A, phospho-PKR levels were diminished in K1-expressing cells transfected with 250 or 500 ng of poly(I-C) in comparison with pCI-transfected cell controls. PKR was not activated by lower amounts of poly(I-C) (50 or 100 ng) nor by transfection of cells with either only pCI or pK1L. The inhibitory effect of the K1 protein was lost when cells were transfected with 1 μg (Fig. 7A) or 3 μg of poly(I-C) (Fig. 7B), indicating that the K1 effect could be overcome. PKR protein production remained unchanged in all samples, indicating that the changes in phospho-PKR levels were not due to varying amounts of PKR. When RNA was collected from cells infected with a virus known to activate PKR (S2C#2) (7) and subsequently used for transfection, phospho-PKR was decreased in pK1L-transfected cells (Fig. 7B). In contrast, RNA from cells infected with a virus known to inhibit PKR activation (S2C#3) (7) stimulate PKR at very low levels in the absence of K1, and p-PKR was undetectable in the presence of K1 (Fig. 7B). As anticipated, RNAs from mock-infected HeLa cells did not elicit PKR activation when transfected regardless of whether K1 was present.

FIGURE 7.

Ectopically expressed K1 inhibits PKR activation. Subconfluent HeLa monolayers were transfected with either the vector backbone (pCI) or HA-K1L plasmid (pK1L). At 18 h post-transfection, cells were mock-transfected (−), transfected with the indicated amounts of poly(I-C) (A) or transfected with 3 μg of either poly(I-C) or RNA isolated from vaccinia-infected HeLa cells (B). At 6 h after the final transfection, cells were lysed, and 25 μg of cytoplasmic proteins from each sample was analyzed by immunoblotting. Immunoblots (IB) were incubated with antibodies specific for either phosphorylated PKR (p-PKR) or unmodified PKR. The same immunoblots were incubated with antiserum raised against the HA epitope (HA) to detect HA-K1 products. Molecular weight markers (MW) are indicated.

VACV K1 Protein Is Required to Inhibit Virus-induced NF-κB Nuclear Translocation in RK13 Cells

PKR mediates several antiviral effects, including NF-κB activation (2). The K1 protein was reported to inhibit both PKR and NF-κB activation (7, 13). Furthermore, the K1 protein inhibited the transcription of the NF-κB-controlled interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor genes (13), and we hypothesized that the ability of K1 to inhibit NF-κB activation was due to its PKR inhibitory function. In support of this hypothesis, we observed that mutant VACVs that no longer inhibit PKR activation (7) also did not prevent NF-κB nuclear translocation (Table 1). For example, ΔK1L infection of RK13 cells stimulates PKR, whereas WR infection of RK13 cells does not (7). We observed that ΔK1L infection activated NF-κB whereas WR infection did not (Fig. 8A). Similarly, re-introduction of the wild-type K1L gene into MVA (MVA/K1L) blocked MVA-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 8A). With either MVA or ΔK1L infection, NF-κB nuclear translocation occurred early in the virus replication cycle, and activation was sustained over the times tested. In contrast, using nuclear extracts from cells infected with a wild-type VACV (WR) or MVA/K1L, this band was less intense as infections proceeded (Fig. 8A).

TABLE 1.

Effect of virus infection on PKR or NF-κB activation

| Virus | Descriptiona | RK13 | HeLa | Knockdownb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKRc | NF-κBd | PKRc | NF-κBd | PKRc | NF-κBd | ||

| WR | Wild-type vaccinia virus | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | ND | ND |

| ΔK1L | WR lacking the K1L gene | Active | Active | Inactive | ND | ND | ND |

| vC7L−K1L− | WR lacking C7L and K1L genes | Active | Active | Active | Active | ND | ND |

| vC7L−K1L+ | K1L-V5 gene inserted into vC7L−K1L− | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| S2N (vC7L−S2N+) | K1-V5 mutated at N terminus of ANK2 (amino acids 63, 67 and 70–75) | Active | Active | Inactive | Inactive | ND | ND |

| S2C (vC7L−S2C+) | K1-V5 mutated at C terminus of ANK2 (amino acids 78, 79, 82, 83, 85, and 87–90) | Active | Active | Active | Active | Inactive | Inactive |

| S2C#2 (vC7L−S2C#2) | K1-V5 mutated at amino acids 81, 82, and 84 | Active | Active | Active | Active | Inactive | Inactive |

| S2C#3 (vC7L−S2C#3+) | K1-V5 mutated at amino acids 86–88 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | ND | ND |

a Data are as described in Ref. 14.

b Data are as described in Ref. 12.

c Data are as reported in Ref. 7. PKR activity was measured by the presence of eIF2α phosphorylation (RK13 cells) or PKR phosphorylation (HeLa or knockdown cells) in infected cell lysates. ND means not determined.

d Cells were infected with the indicated viruses, and NF-κB nuclear translocation, as a measure of NF-κB activation, was assessed by using gel mobility shift assays. Results are shown in this manuscript.

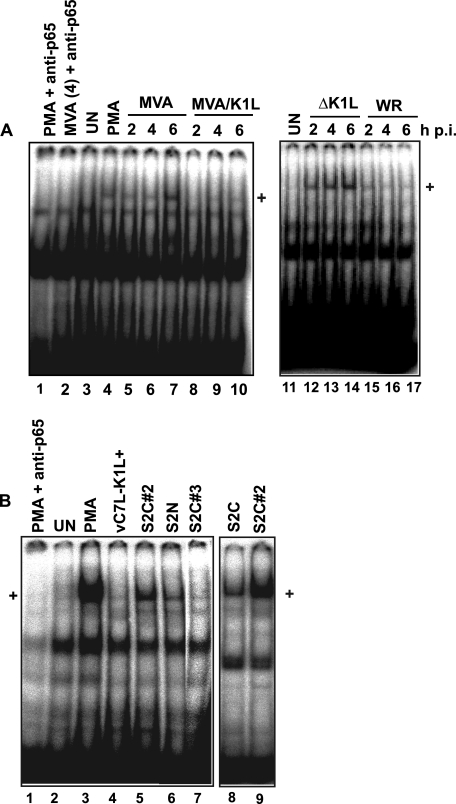

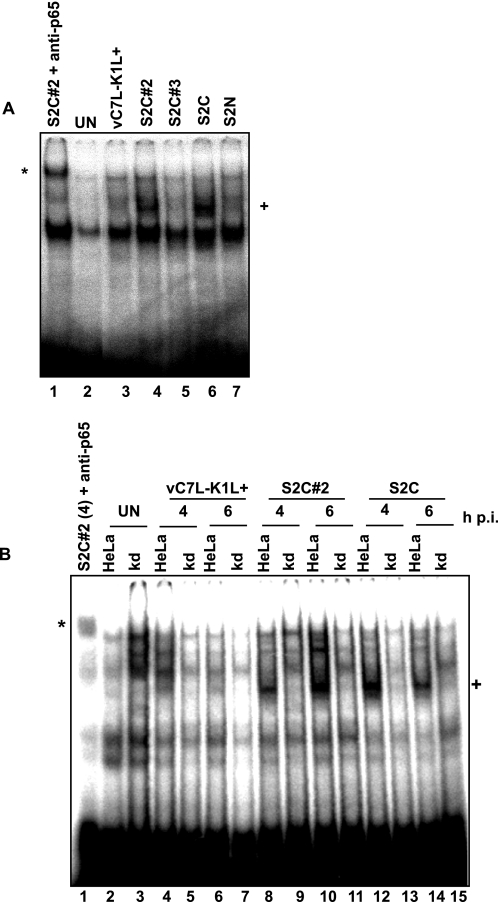

FIGURE 8.

K1L gene is required to inhibit NF-κB activation during infection of RK13 cells. RK13 cells were mock-infected (UN) or infected with the indicated vaccinia viruses (m.o.i. = 10). Infected cells were harvested at 2, 4, or 6 h pi (A) or 4 h pi (B). In some experiments, a separate set of mock-infected cells was incubated in medium containing phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (50 nm) for 4 h before harvesting. Cells were lysed, and nuclear proteins were extracted. Five μg of protein from each sample were incubated with 32P-radiolabeled oligonucleotides that contain an NF-κB-binding site. Reactions were analyzed using an EMSA. Gels were dried, and radioactivity was detected by phosphorimaging. Shifted bands containing NF-κB are indicated with a +. In some reactions, anti-p65 antibody was added.

The K1 protein possesses 9 ankyrin repeats (28), and the K1 ANK2 region possesses PKR inhibitory function (7). We have identified the ANK2 residues critical for PKR inhibitory function, using four viruses with substitution mutations within the K1 ANK2 region (Table 1) (7, 14). The four recombinant viruses containing wild-type or mutated K1L genes used are S2N, S2C, S2C#2, and S2C#3 (Table 1) (14). All viruses lack the C7L gene. Virus S2N expresses a mutant K1L gene whose product was mutated at residues 63, 67, and 70–75, in the N-terminal portion of ANK2 (14). Virus S2C encodes a K1 product, in which ANK2 C-terminal residues 78, 79, 82, 83, 85, and 87–90 are mutated (14). Viruses S2C#2 and S2C#3 express mutant K1L products in which the ANK2 C-terminal residues 81, 82, and 84 or 86–88 are mutated, respectively (14).

When evaluating the NF-κB activation state in cells infected with these same viruses, it was observed that there was a 100% correlation between the ability of a mutant virus to inhibit PKR and NF-κB (Table 1). For example, in RK13 cells, we observed that viruses S2N, S2C, and S2C#2 stimulated NF-κB translocation to a greater degree than cells infected with viruses expressing a wild-type K1 protein or S2C#3 (Fig. 8B). Extracts from uninfected cells treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, a known activator of NF-κB, produced a band with mobility similar to that observed with S2N-, S2C-, or S2C#2-infected cells (Fig. 8B); this band disappeared when an anti-NF-κB antibody (anti-p65) was added to this reaction, verifying that NF-κB was present in this band.

The same trend was also observed in infected HeLa cells; those viruses that permitted PKR activation also permitted NF-κB nuclear translocation (Table 1). For example, NF-κB nuclear translocation occurred when HeLa cells were infected with VACVs that allow PKR activation (S2C#2 and S2C) (Fig. 9A). However, when cells were infected with viruses that prevented PKR phosphorylation in HeLa cells (vC7L-K1L+, S2C#3, or S2N), NF-κB remained cytoplasmic, comparable with the state observed with uninfected cells.

FIGURE 9.

PKR is responsible for virus-induced NF-κB activation in HeLa cells. A and B, HeLa cells expressing PKR (HeLa) or lacking PKR (KD) (B) were mock-infected (UN) or infected with the indicated viruses (m.o.i. = 10). Cells were harvested at 4 h pi, unless otherwise noted, and nuclear proteins were extracted. Two μg of protein from each sample was incubated with 32P-radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing the promoter of the human TLR2 gene. Reactions were analyzed using an EMSA. Shifted bands containing NF-κB are indicated with a +. Anti-p65 antibody was added to reactions in lane 1 of each gel, and the resulting supershifted band is indicated by an asterisk.

PKR Protein Is Necessary to Activate NF-κB in VACV-infected Cells

The above results implied that PKR was acting upstream of NF-κB. To directly test the hypothesis that inhibition of K1 of PKR also was its mechanism to inhibit NF-κB activation, we evaluated virus-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation in PKRkd (knockdown) cells, HeLa cells in which >95% of PKR protein expression is stably silenced (12). As shown in Fig. 9B and Table 1, infection of either wild-type HeLa cells or knockdown cells with the parental vC7L−K1L+ resulted in low levels of NF-κB nuclear translocation, similar to that of uninfected HeLa or knockdown cells. Infection of HeLa cells with either S2C or S2C#2 stimulated NF-κB nuclear translocation above that of uninfected cells. However, when knockdown cells were infected with either S2C#2 or S2C viruses, NF-κB nuclear translocation was no longer observed, implying that PKR proteins were required for virus-mediated NF-κB nuclear translocation. Importantly, robust NF-κB nuclear translocation was observed when knockdown cells were treated with either tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, demonstrating that the general NF-κB activation pathways were functional in this cell line (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Historically, the identification of viral mechanisms important for virus survival has revealed cellular proteins with important antiviral effects. For example, PKR was discovered when it was observed that interferon treatment of VACV-infected cells restricted the translation of viral mRNAs (29–31). Our data expand the current view of PKR activation during a poxvirus infection. Previously, it was thought that only intermediate and late gene transcripts formed dsRNA to activate PKR, with the E3 or K3 proteins preventing PKR activation (3, 5, 32–34). We now propose the following: (i) early gene transcripts also possess PKR-activating properties, and (ii) K1 protein inhibits PKR activation when PKR is induced by dsRNA formed from either early or intermediate gene transcripts.

mRNAs transcribed from early genes were thought to be a homogenous population due to the presence of the transcription termination sequence UUUUUNU in early viral mRNAs (35, 36). Thus, early gene transcripts were not expected to form dsRNA nor stimulate PKR. Several lines of evidence, in addition to evidence presented here using RK13 cells, refute this model. First, it has been reported that transcripts with a single termination sequence are terminated with an efficiency rate of 80% (37), implying that the 3′ ends of early mRNA populations are not as homogeneous as once believed. Second, low amounts of dsRNA have been detected in VACV-infected cells, in support of our findings (38). Thus, dsRNAs other than those detected here also may be generated during VACV infection. Third, deep RNA sequencing of the VACV transcriptome identified the presence of small antisense transcripts (21). As PKR requires a minimum of 30 nucleotides of dsRNA for activation, binding of these small antisense transcripts to viral mRNAs could also result in formation of dsRNA and induce PKR activation (21, 39).

In contrast to infection of RK13 cells, PKR-activating dsRNA was formed during poxviral intermediate gene transcription in HeLa cells. Notably, Ara C treatment of S2C#2-infected cells inhibited PKR activation, identifying either intermediate or late gene transcription as the PKR activating function. Because replication of S2C#2 in HeLa cells is blocked after intermediate gene transcription (14, 23), we concluded that intermediate mRNA molecules must form dsRNA to induce PKR activation. In support of this, dsRNA was detected by immunofluorescence microscopy in S2C#2-infected cells. It has been reported previously that intermediate mRNA, like late gene transcripts, have heterogeneous 3′ ends (33, 40). More recently, it was shown that intermediate mRNA from cells infected with MVA (a replication-deficient VACV that lacks a wild-type K1L gene) indeed forms dsRNA that possesses PKR activating function (41), agreeing with our data.

Interestingly, regardless of cell type, the presence of the K1 protein correlated with reduced dsRNA levels in infected cells; dsRNA is increased in cells infected with VACVs that do not prevent PKR activation (ΔK1L or S2C#2) versus viruses that contain wild-type K1L genes (WR or vC7L−K1L+). One possibility is that the K1 protein acts as a facilitator of translation, and in its absence, an abundance of mRNAs is present. There are several studies that support this model. For example, in ΔK1L-infected RK13 cells, only early gene transcription occurs (8). Moreover, the early gene transcripts in these infected cells are detected for longer periods of time than transcripts from WR-based infections (8). For vC7L-K1L-infected HeLa cells, replication is blocked after intermediate gene transcription (14, 23). Thus, the increased presence of early or intermediate mRNA molecules would trigger dsRNA formation. If the K1 protein was indeed aiding the translation of viral mRNAs, then it would act at a step upstream of the E3 and K3 protein to inhibit PKR activation (Fig. 10). Specifically, although the E3 and K3 proteins prevent dsRNA-PKR interactions, the K1 protein would prevent the initial formation of dsRNAs.

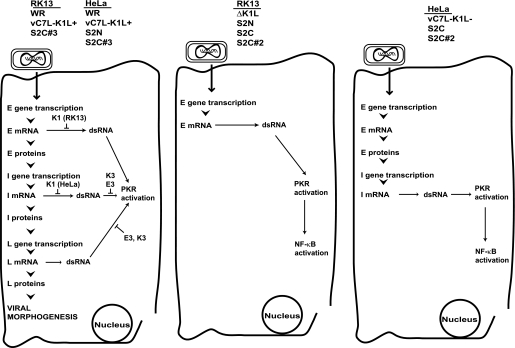

FIGURE 10.

Model of PKR-induced NF-κB activation triggered by vaccinia virus infection in RK13 or HeLa cells. Left panel, gene expression that occurs during a wild-type vaccinia virus infection in either RK13 or HeLa cells or in cells infected with the viruses listed above the diagram. Poxviral gene expression occurs temporally, with the early (E) class of genes transcribed first, followed by the expression of intermediate (I) and late (L) class of genes. It is well known that the intermediate and late gene transcripts produce dsRNA. For these, the vaccinia E3 and K3 proteins interact with dsRNA or PKR to prevent PKR activation. We now propose that the transcription of early genes also produces dsRNA. In addition, we show that the K1 protein inhibits early dsRNA-induced PKR activation in RK13 cells and intermediate dsRNA-induced PKR activation in HeLa cells. In both cases, we propose that the K1 protein functions upstream of E3 or K3, by facilitating the translation of viral mRNAs. Middle panel, in RK13 cells, when wild-type K1L is absent or the mutants S2N, S2C, or S2C#2 K1 proteins are present, early gene transcription causes dsRNA formation, resulting in PKR activation and downstream NF-κB activation. Right panel, in HeLa cells infected with a virus lacking the K1L gene (vC7L−K1L−), or expressing the mutant S2C or S2C#2 K1 proteins, intermediate gene transcription causes dsRNA formation, resulting in PKR activation and downstream NF-κB activation.

We observed that ectopically expressed K1 proteins prevented poly(I-C)-induced PKR activation. Thus, another possible function for the K1 protein is that it inhibits dsRNA-PKR interactions. However, we did not detect K1-dsRNA interactions by co-immunoprecipitations (data not shown), suggesting that the K1 protein does not bind to dsRNA. To assess whether K1-PKR interactions are important for PKR inhibitory function, our one future direction is to assess if those K1 proteins that permit PKR activation also do not interact with PKR.

We have considered that K1 may act indirectly to diminish dsRNA levels by acting on RNase L. There are several lines of evidence that suggest this is not the case. First, a mutation in the A18R gene is known to increase RNase L levels, as measured by rRNA cleavage (42). We assume that the A18L gene is wild type in all viruses used here and that RNase L would be inhibited during infections, regardless of the presence or absence of K1L. Moreover, we did not detect rRNA degradation, an indirect measure of RNase L activity (41, 42), in infected cells where the K1 protein either inhibits (WR or S2C#3 infection) or permits (S2C#2) PKR activation (data not shown), suggesting that the K1 protein does not act on RNase L. Moreover, in support of our data, Backes et al. (41) show that RNase L is not active when cells are infected with vaccinia viruses that either lack or contain the K1L gene.

It is curious why early viral gene transcripts possessed PKR stimulating activity for infected RK13 cells but not HeLa cells. One possibility is that there is a VACV protein that inhibits dsRNA-induced PKR activation from early gene transcripts in HeLa cells but not in RK13 cells. The VACV K3 protein does not possess PKR inhibitory function in human HeLa cells, ruling it out as an effector (6, 43). The VACV C7 protein is also known to inhibit PKR activation (41, 44). However, the recombinant viruses used in our studies of HeLa cells lack the C7L gene (14), eliminating it as a gene with a possible effect. Why E3 is not binding to dsRNA from early or intermediate transcripts sufficiently to inhibit PKR is unknown, and it may be due to differences in RNA binding specificities, subcellular locations, or protein concentrations at different times during infection.

It was observed that RNase A/T1-treated RNA possessed a greater PKR activating effect than undigested RNA. One explanation of this result is that extracted RNA may contain complexes of RNA that are partially single-stranded and partially double-stranded in nature. This web-like formation, in which only some of the RNA is perfectly base-paired as dsRNA, previously has been formed from late gene transcripts (27). As such, it is possible that early gene transcripts may form a similar structure and, upon digestion of single-stranded RNA, the remaining dsRNA would bind to and activate PKR more effectively.

It was also curious as to why RNase A/T1-treated RNA from virus-infected cells can activate PKR (Fig. 2B), but it does not allow the PCR amplification of A4L-A5R or A46R-A47L dsRNA regions (Fig. 3). It is unknown how many viral dsRNA molecules are required to activate PKR. One possibility for these results is that the dsRNA generated by A4L-A5R and A46R-A47L is not enough to activate PKR. However, during a vaccinia virus infection, other dsRNA regions from early gene transcription are present,7 and these dsRNAs, in combination with the dsRNA from A4L-A5R and A46R-A47L, may be enough to stimulate PKR activation.

Activated PKR is best known as mediating eIF2α phosphorylation during virus infection and has been shown to activate NF-κB during poxvirus infection (9, 11, 45). For example, an attenuated strain of VACV, MVA, must stimulate PKR to activate NF-κB (9). Moreover, overexpression of PKR in poxvirus-infected cells results in NF-κB activation (10, 46). The K1 protein was reported to inhibit both PKR and NF-κB activation (7, 13). Thus, we hypothesized that PKR inhibition by the K1 protein was responsible for the ability of K1 to inhibit NF-κB activity (13). We previously characterized a set of VACVs that possessed mutations in the ANK2 region for their ability to inhibit PKR activation in RK13 and HeLa cells (7). We used these same viruses to assess the relationship between PKR and NF-κB. We observed a 100% correlation between a virus activating PKR and activating NF-κB (Table 1). We interpreted these results to mean that PKR was acting upstream and was responsible for stimulating NF-κB. Indeed, in HeLa cells, the absence of PKR results in a lack of NF-κB activation, implying that PKR acts upstream and is required for NF-κB activation. At least two other poxvirus proteins, CP77 and E3, possess the dual function of inhibiting PKR and NF-κB activation (11). E3, which binds to dsRNA or PKR, also inhibits NF-κB activation by preventing PKR activity in VACV-infected cells (12). In contrast, the CP77 protein likely possesses two distinct mechanisms to inhibit PKR and NF-κB activation; CP77 binds to the p65 subunit of NF-κB via both N-terminal ankyrin repeats and an F-box like domain in the C-terminal portion of CP77 (23, 47). Although K1 is homologous to CP77 due to the presence of ankyrin repeats, K1 possesses no apparent F-box sequence (8).

In summary, this study demonstrates a previously unappreciated role of early mRNA for PKR activation. Moreover, we found that the K1 protein can inhibit PKR activation triggered by either early or intermediate gene transcripts. By inhibiting PKR, the VACV K1 protein inhibits the downstream signaling pathways such as NF-κB. VACV is widely used as a vaccine to protect against smallpox and as a vector for oncolytic therapy or vaccines against other pathogens. Genetic manipulation of VACV is often attempted to create safer, more effective vaccines and therapeutic vectors. Deletion of other VACV host-range proteins that inhibit PKR, such as E3, have yielded vaccine strains that were both effective at eliciting an immune response and less pathogenic, the ultimate goal of vaccine development (15). K1L-deficient viruses or viruses devoid of both E3L and K1L may prove to have similar or superior vaccine properties.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Amy MacNeill and Gail Scherba for critical review of this manuscript, Dr. Edward Roy for assistance with immunofluorescent microscopy, and Drs. Zhilong Yang and Bernard Moss for their helpful discussion concerning vaccinia transcriptome regions with dsRNA regions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI055530 from NIAID (to J. L. S.).

W. Arndt, C. Mitnik, K. Denzler, S. White, R. Waters, B. Jacobs, Y. Rochon, V. Olson, I. Damon, and J. Langland, submitted for publication.

Z. Yang and B. Moss, personal communication.

Y. Xiang, personal communication.

Z. Yang and B. Moss, personal communication.

- dsRNA

- double-stranded RNA

- VACV

- vaccinia virus

- nt

- nucleotide

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

- COR

- cordycepin

- Ara C

- cytosine arabinoside

- SPE

- S. purpurea plant extract

- WR

- Western Reserve

- pi

- post-infection

- ssRNA

- single-stranded RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Raven J. F., Koromilas A. E. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 1146–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. García M. A., Meurs E. F., Esteban M. (2007) Biochimie 89, 799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moss B. (2007) in Fields Virology (Knipe D., Howley P. eds) 5th Ed., pp. 2905–2946, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 4. Condit R. C., Niles E. G. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1577, 325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang H. W., Watson J. C., Jacobs B. L. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 4825–4829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langland J. O., Jacobs B. L. (2002) Virology 299, 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Willis K. L., Patel S., Xiang Y., Shisler J. L. (2009) Virology 394, 73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ramsey-Ewing A. L., Moss B. (1996) Virology 222, 75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lynch H. E., Ray C. A., Oie K. L., Pollara J. J., Petty I. T., Sadler A. J., Williams B. R., Pickup D. J. (2009) Virology 391, 177–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gil J., Rullas J., Alcamí J., Esteban M. (2001) J. Gen. Virol. 82, 3027–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Myskiw C., Arsenio J., van Bruggen R., Deschambault Y., Cao J. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 6757–6768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang P., Jacobs B. L., Samuel C. E. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 840–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shisler J. L., Jin X. L. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 3553–3560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meng X., Xiang Y. (2006) Virology 353, 220–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobs B. L., Langland J. O., Kibler K. V., Denzler K. L., White S. D., Holechek S. A., Wong S., Huynh T., Baskin C. R. (2009) Antiviral Res. 84, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weaver J. R., Shamim M., Alexander E., Davies D. H., Felgner P. L., Isaacs S. N. (2007) Virus Res. 130, 269–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gedey R., Jin X. L., Hinthong O., Shisler J. L. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 8676–8685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bond M., Chase A. J., Baker A. H., Newby A. C. (2001) Cardiovasc. Res. 50, 556–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson C. M., Lyle E. A., Omueti K. O., Stepensky V. A., Yegin O., Alpsoy E., Hamann L., Schumann R. R., Tapping R. I. (2007) J. Immunol. 178, 7520–7524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin S., Shisler J. L. (2009) Virology 390, 298–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang Z., Bruno D. P., Martens C. A., Porcella S. F., Moss B. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11513–11518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perkus M. E., Goebel S. J., Davis S. W., Johnson G. P., Limbach K., Norton E. K., Paoletti E. (1990) Virology 179, 276–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsiao J. C., Chung C. S., Drillien R., Chang W. (2004) Virology 329, 199–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Esteban M., Metz D. H. (1973) J. Gen. Virol. 20, 111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beaud G., Dru A. (1980) Virology 100, 10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weber F., Wagner V., Rasmussen S. B., Hartmann R., Paludan S. R. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 5059–5064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pichlmair A., Schulz O., Tan C. P., Rehwinkel J., Kato H., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Way M., Schiavo G., Reis e Sousa C. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 10761–10769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li Y., Meng X., Xiang Y., Deng J. (2010) J. Virol. 84, 3331–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kerr I. M., Brown R. E., Ball L. A. (1974) Nature 250, 57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kerr I. M., Friedman R. M., Brown R. E., Ball L. A., Brown J. C. (1974) J. Virol. 13, 9–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Friedman R. M., Esteban R. M., Metz D. H., Tovell D. R., Kerr I. M., Williamson R. (1972) FEBS Lett. 24, 273–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beattie E., Tartaglia J., Paoletti E. (1991) Virology 183, 419–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baldick C. J., Jr., Moss B. (1993) J. Virol. 67, 3515–3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ludwig H., Suezer Y., Waibler Z., Kalinke U., Schnierle B. S., Sutter G. (2006) J. Gen. Virol. 87, 1145–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shuman S., Moss B. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 6220–6225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yuen L., Moss B. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6417–6421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Earl P. L., Hügin A. W., Moss B. (1990) J. Virol. 64, 2448–2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boone R. F., Parr R. P., Moss B. (1979) J. Virol. 30, 365–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robertson H. D., Mathews M. B. (1996) Biochimie 78, 909–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ludwig H., Mages J., Staib C., Lehmann M. H., Lang R., Sutter G. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 2584–2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Backes S., Sperling K. M., Zwilling J., Gasteiger G., Ludwig H., Kremmer E., Schwantes A., Staib C., Sutter G. (2010) J. Gen. Virol. 91, 470–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bayliss C. D., Condit R. C. (1993) Virology 194, 254–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Beattie E., Paoletti E., Tartaglia J. (1995) Virology 210, 254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nájera J. L., Gómez C. E., Domingo-Gil E., Gherardi M. M., Esteban M. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 6033–6047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Langland J. O., Cameron J. M., Heck M. C., Jancovich J. K., Jacobs B. L. (2006) Virus Res. 119, 100–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gil J., García M. A., Gomez-Puertas P., Guerra S., Rullas J., Nakano H., Alcamí J., Esteban M. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 4502–4512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chang S. J., Hsiao J. C., Sonnberg S., Chiang C. T., Yang M. H., Tzou D. L., Mercer A. A., Chang W. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 4140–4152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]